Introduction

For postwar Italy, the process of negotiating the legacies of Fascism has been both volatile and multifaceted. This is evidenced by the treatment of the military ossuaries, or bone depositories, which were created under the Fascist regime to house the bodies of fallen soldiers of the First World War. Built in 1929–1939 close to the former frontlines of north-eastern Italy and present-day Slovenia, the ossuaries were steeped in the symbols of Fascist nationalism, militarism, and imperialism. Having lost their original purpose as carriers of Fascist propaganda, they now hold an awkward position as national monuments and elements of a history that can prompt uncomfortable memories. In that they function both as memorials to the fallen and as remnants of Mussolini’s regime, they reflect ambiguities inherent in Italy’s handling of the legacy of Fascism. Moreover, as part of Italy’s centennial commemorations of the First World War, the ossuaries have recently been returned to a position of prominence. For example, in the midst of struggles to form a new government in April 2018, it was politically expedient for Matteo Salvini, leader of La Lega and soon to be Deputy Prime Minister, to visit the ossuary at Redipuglia (1938) with ‘a prayer for the young men who fell … to defend … the borders and the future of their children’.Footnote 1 Other ossuaries have been used to accommodate centennial rituals, and some are undergoing restoration work that is funded by the state.

Over the postwar period, the political meanings associated with Italy’s ossuaries have been both useful and inconvenient. In unpacking this paradox, it is helpful to explore the Fascist origins of the ossuaries and the political intentions that they were built to serve, changes in their status and treatment from 1945, and their role in the centennial commemorations of the First World War. In particular, it is important to address the notion that Fascist remains constitute a ‘difficult heritage’ in the form of sites ‘that are historically important but heavily burdened by their past’ (Burström and Gelderblom Reference Burström and Gelderblom2011, 267; also, Logan and Reeves Reference Logan and Reeves2008; Macdonald Reference Macdonald2009; Samuels Reference Samuels2015). Using the ossuaries as a testbed, it is possible to challenge the emphasis that is laid on the political or ideological difficulties of dealing with Fascist remains. As monuments whose reception has altered over time, and whose meanings have been rewritten with the passage of history, the Italian ossuaries now appear to have been comfortably integrated into the national heritage. However, they have been awarded a range of different meanings and associations, and the processes of integration have been dynamic, complex, and relatively arduous. Thus, it is better to think of the ossuaries, not simply as difficult heritage that is associated exclusively with Fascism, but as palimpsests that have been overlaid with different memories; which may, in turn, have been rewritten or erased (Brooke-Rose Reference Brooke-Rose1992; Dillon Reference Dillon2005; Foot Reference Foot2009, 4; Macdonald Reference Macdonald2009, 191–192). Clearly, the meanings carried by a building can alter with the passage of time; that is, they must reflect the periods through which a building passes, the different political and cultural contexts that influence its interpretation, and the communities and collective memories through which it gathers various associations (Huyssen Reference Huyssen2003, 7; Bosworth Reference Bosworth2011, 1–9; Kallis Reference Kallis2014, 2–3). Moreover, the memories attached to buildings are subject to individuation. Different individuals or groups privilege different meanings, or favour associations that reflect the status of monuments as local, national or international entities. Different contexts and communities shape divergent narratives. As palimpsests, the ossuaries have been readily absorbed into the national heritage, and into Italy’s centennial commemorations. In fact, they have been subject to various and complex strategies of selection and revision that should offset a one-dimensional approach to Fascist remains as difficult heritage, or as little more than symbols of a Fascist history.

Origins under Fascism

The First World War brought death to over half a million Italian soldiers and bloodshed on a scale that was unprecedented in Italian history. Over 300,000 of the soldiers fell in battle and were buried in makeshift cemeteries or mass graves close to battlefields. Immediately after the war, those burial places were reorganised as small cemeteries that were scattered along the former frontlines – cemeteries that were akin to their civilian counterparts, and under the control of local councils (Bregantin Reference Bregantin2010, 49–87; Reference Bregantin2011). Roughly, a further 170,000 soldiers who died of illness or injury were interred in major urban cemeteries across Italy. Of the total number of the fallen, only around 50,000 were repatriated or returned to the families (Bregantin and Brienza Reference Bregantin and Brienza2015, 42).

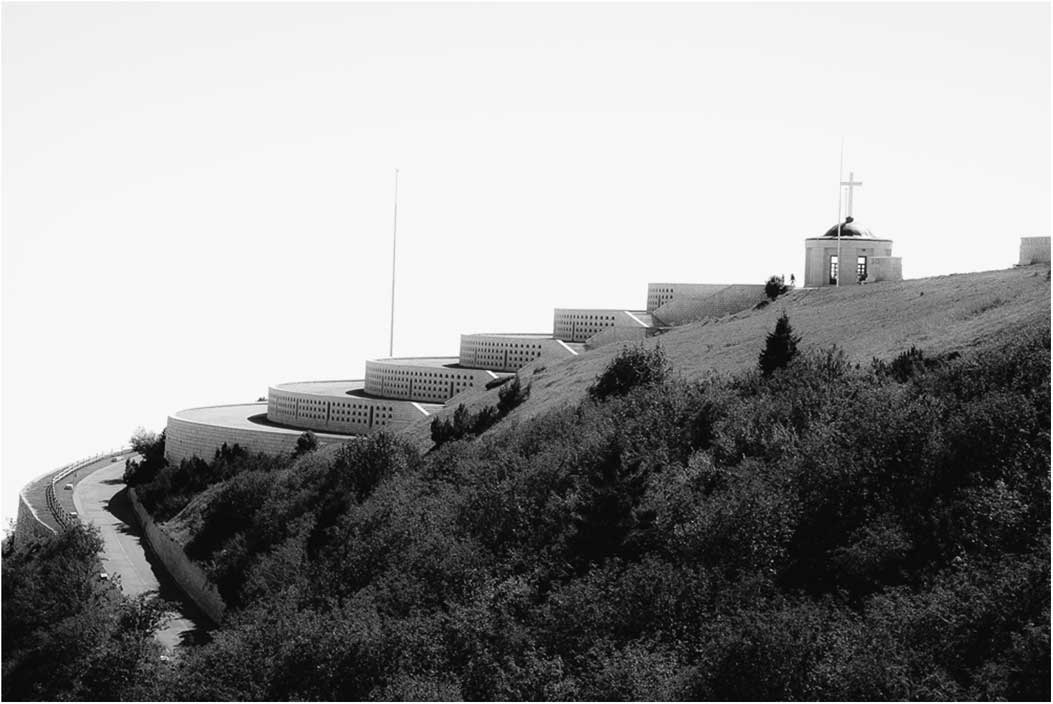

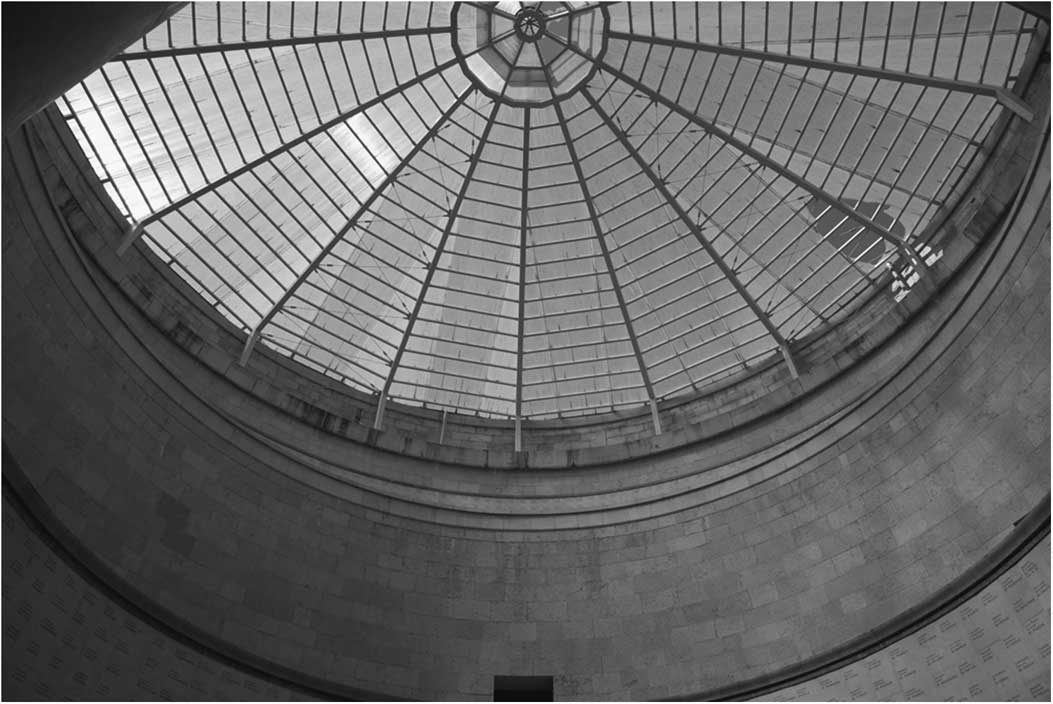

In 1927, the Fascist authorities denounced the modesty of the frontline cemeteries. As victory in the First World War was a core element of Fascist propaganda, Mussolini demanded a more grandiose approach to the commemoration of the fallen. Charged by Mussolini to find an honourable solution, General Giovanni Faracovi suggested the exhumation of hundreds of thousands of soldiers who died at the front, and the removal of their remains to new ossuaries that were to be built close to earlier burial grounds and to former battlefields. That strategy met with Mussolini’s approval, and was enacted into law in 1931. The Duce then appointed Faracovi as head of a military commission that was responsible for soldiers who fell in Italy or abroad (Dogliani Reference Dogliani1992; Fiore 2001; Malone Reference Malone2015; Bregantin and Brienza Reference Bregantin and Brienza2015).Footnote 2 Thus, from the early 1930s, the remains of known and unknown soldiers were exhumed from the battlefield cemeteries under the surveillance of priests, and were placed in wooden boxes in preparation for their relocation under military escort. The redundant battlefield cemeteries were generally demolished; including, for instance, the renowned burial site at Colle Sant’Elia (Foot Reference Foot2009, 46–48; Malone Reference Malone2015, 27). Ultimately, the programme resulted in 36 new ossuaries, which brought together remains that had previously been interred in roughly 2,650 burial grounds. For instance, the relatively small ossuary of Montello (1935) holds nearly 9,000 bodies that were removed from 138 cemeteries located in the surrounding area close to the Piave River. The largest of the ossuaries is at Redipuglia in Friuli, within which a giant staircase incorporates the remains of over 100,000 soldiers, of which approximately 60,000 were unknown or unidentifiable (Figure 1). In effect, the concentration of the dead provided the scale and grandeur demanded by Mussolini and the needs of Fascist propaganda. Meanwhile, the commission also entered into partnerships with local councils or clerical bodies to transfer to new urban ossuaries the remains of soldiers who had died behind the frontlines. Priority was given to soldiers who were killed in action, for whom the military commission built the largest and most significant of the ossuaries in remote areas close to former frontlines in the Italian regions of Veneto, Friuli, and Trentino, and in Slovenia.

Figure 1 Ossuary at Redipuglia, inaugurated in 1938 (author’s photograph 2014). Note that fasces have been removed from either side of the inscription.

While they contributed to an official policy to turn battlefields into monumental sites, a number of the ossuaries also exploited spectacular locations in open and mountainous landscapes, as at Monte Grappa (Figure 2). Some ossuaries, such as Redipuglia, were located in areas once held by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and which fell to Italy after the First World War. As such, they marked new territories that witnessed the ‘italianisation’ of local Slavic and German populations, and the brutal repression of regional languages and cultures (Vinci Reference Vinci2011, 161–168; Pergher Reference Pergher2018a, 63–64). Given that these territories had been populated by many who fought or died on the side of Austria-Hungary, regional memories and an opposition to Italian nationalism coloured the reception of the ossuaries built on conquered land (Foot Reference Foot2009, 10–11; Rumiz Reference Rumiz2014, 104–105).

Figure 2 Ossuary at the apex of Monte Grappa, built in 1932–1935 (author’s photograph 2014).

Meanwhile, the geographical concentration of the dead within the ossuaries reflected the centralisation of political power by the Fascist state (Gentile Reference Gentile2009, 215; Isnenghi Reference Isnenghi2004, 307–310). The creation of the monuments marked the apex of a gradual process through which control over the fallen was passed to the military as an agent of the Fascist regime – a process that began before Mussolini’s ascent to power, and which accelerated rapidly in the late 1920s. While previously, remembrance of the fallen had been left to mourners, local councils, and veterans’ groups, after 1928 both monuments and ceremonies commemorating the war dead were either prohibited or subject to state approval. Through compromise and coercion, control over the methods of remembrance shifted from civil society and the Church to the military, which, in monopolising commemoration, allowed its political advantages to pass to the state.

The authorities justified the programme of reburial as a practical and economical solution to the problem of small, scattered, and degrading cemeteries. However, as expressed in the report that accompanied General Faracovi’s programme of reburial, the primary motivations were political (Faracovi Reference Faracovi1930). For the Fascist leadership, the fallen presented an opportunity to be exploited. The First World War held a central place in Fascist ideology as a foundational myth and as a source of legitimation (Fogu Reference Fogu2001; Sabbatucci Reference Sabbatucci2003). The war had divided Italians and elicited powerful reactions of support and opposition. The peace negotiations brought disappointment, and deepened divisions between those for whom the war was either a glorious triumph or a pointless slaughter. From this fracture, the Fascist leadership emerged to impose its own formulated interpretations of the past. It promised to heal divisions and to unify the nation under memories of a triumphant war – and as the regime cast itself as heir to an Italian victory, the war became a keystone of Fascist propaganda.

Within that context, the programme of reburial represented a chance to impose a victorious vision of loss and sacrifice, and an opportunity to harness a nation’s grief to the Fascist cause. As tools of propaganda, the ossuaries were intended to cast the war as a triumph. At Monte Grappa, a hilltop Via Eroica constitutes a heroic route to victory, which is flanked by slabs that commemorate various battles (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Visitor to the ossuary at Monte Grappa (author’s photograph 2014).

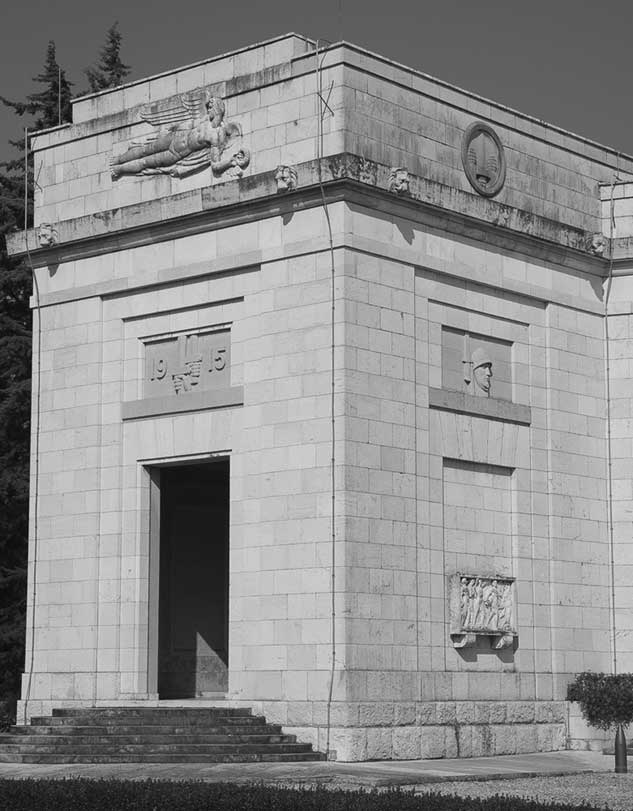

The gigantic forms and classicised aesthetics of the ossuaries conveyed core principles of Fascist ideology relating to power, victory, and political unity. They also encouraged a veneration of the fallen as ‘martyrs’ of the fatherland. At Redipuglia, for example, the three crosses at the top of the ossuary suggest a Christ-like sacrifice made by the fallen for the redemption of the nation (Figure 1). As a useful political tool, this cult of the dead was meant to foster national cohesion and to glorify the Fascist regime. In time, the ossuaries were also meant to serve as a call to arms, as the living were led to believe that they owed it to the fallen to fight for their country in future wars. As with the decoration at Fagarè, a rhetoric rooted in glorious heroism expressed a positive vision of war that was meant to prepare the nation for new conflicts (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Survival of Fascist symbols on the ossuary at Fagarè, completed in 1935 (author’s photograph 2014).

Moreover, in gathering millions of bones into ossuaries, the regime sought to create secular sites of pilgrimage and significant events. The political value of the ossuaries was also enhanced through a campaign of propaganda that included films, photographs, newspaper articles, guidebooks, and pamphlets – propaganda that was largely targeted at veterans and the young.

Following Mussolini’s removal from power in 1943, one of the leaders of the programme of reburial was sanctioned. In 1944, General Ugo Cei, who had occupied the post of commissioner for the burial of the fallen from 1935 to 1941, and who directed the creation of at least 14 major ossuaries, was among the senators removed from their positions by the High Court of Justice for Sanctions against Fascism. Essentially, he was accused of supporting the Fascist regime – an accusation that signalled how, as symbols of Fascism, the ossuaries were cast into a new position by the fall of the dictatorship (Bregantin and Brienza Reference Dato2015, 73–74).

After 1945

In many respects, the postwar fate of the ossuaries is emblematic of Italian attempts to handle the physical legacy of Fascism. With the loss of their intended functions, the ossuaries became ‘historical monuments’ in the sense used by Alois Reigl to indicate artefacts whose original purposes are replaced by new commemorative uses (Reference Riegl1903, 72). However, the treatment of the ossuaries has been relatively inconsistent. Some have been adopted as national monuments while others are largely forgotten. In general, the fate of individual sites might be defined in terms of four common factors: (1) changes in management; (2) physical changes, substantial rebuilding, or subtle alterations in aesthetics and decoration; (3) factors associated with heritage such as the creation of signs or exhibition spaces; and (4) other changes in use that might relate, for example, to tourism, ceremonies, or rituals. These factors may be interrelated: for instance, where changes in use lead to physical alterations, or where management is linked to the transformation of buildings into heritage sites. Changes in form or use will also alter the meanings associated with a site. More importantly, those changes in meaning will reflect the evolution of cultural and political conditions, differences between individuals and groups, and between local and wider geographical contexts.

Institutions

There has been a degree of continuity in the practical administration of the ossuaries in that, shortly after the end of the Second World War, the commission for the burial of the fallen was reconstituted under the Italian Ministry of Defence. In 1951, the commission was charged with repatriating the military dead of both world wars on the basis of requests submitted by families. A revived Fascist-era law of 1935 gave the commission ample powers to dissolve or create cemeteries – a move that was driven by the need to deal with the dead of both world wars, and a desire to maintain a ‘cult of the fallen’, which members of Italy’s parliament saw as a core value of Italian civilisation (Atti Parlamentari, Camera dei Deputati, 4 October 1950). Praised as ‘immortal’ sources of national pride, the ossuaries were embraced as art, and as monuments that accommodated a cult of the dead. Thus, they helped to reinstate the commemoration of the fallen as an instrument of postwar politics, and as a longstanding tradition that was central to the Risorgimento and the foundation of Italy’s national identity, as well as to Fascism (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2010, 36–43: Gentile Reference Gentile2009, 32; Riall Reference Riall2010; Malone Reference Malone2017, 104–128).

Today, the ossuaries are still state-owned and administered by the same military commission, which establishes agreements with local councils regarding their maintenance (Bregantin Reference Bregantin2010, 261). That situation allows the military to encourage an air of respect on the part of visitors. However, notwithstanding the centenary and state-funded projects, the commission is underfunded. It struggles to maintain the ossuaries, some of which are neglected or in need of repair (Figure 5). As at Oslavia (1938) in Friuli, this might be seen as a form of calculated neglect that is meant to distance the public from the Fascist purposes for which the ossuaries were originally created (Macdonald Reference Macdonald2006, 22). However, the neglected state of some monuments may simply reflect their distance from public priorities, or dependency on state funds.

Figure 5 Signs of neglect at the ossuary of Oslavia, completed in 1935 (author’s photograph 2015).

Physical form

The physical state of the ossuaries has signalled their status in postwar Italy. Initially, in common with sites across Italy, they were ‘de-fascistised’ or stripped of some of their Fascist symbols. For example, at Redipuglia fasces were entirely erased, or were ‘castrated’ through the removal of the axe (Figure 1; Benton Reference Benton1999, 218; Fiore 2001, 147). However, as evidenced at Fagarè, most of the Fascist-era decoration remained (1935; Figure 4). In the 1950s, the original structure of the ossuary at Montello was rebuilt following a landslide. Similarly, religious frescoes at Timau (1936) were completed in 1955 following the original designs. Many of the ossuaries have seen only small or decorative changes. Generally, they retain the aesthetics of Fascism, and while much of their symbolic status is inherent in their forms and spaces rather than their decorative details, only total demolition could erase their monumentality.

Heritage management

The transformation of the ossuaries into heritage sites has also played an important role in redefining their status since 1945. While all the sites bear some signage and historical information, since the 1970s some have been fitted with small museums and exhibition spaces, whether in the main or auxiliary buildings. As expressed by the commission for the burial of the fallen in 1996, the purpose of the exhibition spaces is, in part, commemorative.Footnote 3 While they differ in layout and approach, they tend to focus on the First World War rather than on Fascism as the generative context of the ossuaries. Most highlight the technologies of the war, military memorabilia, and the experiences of the common soldier, as at the museum of Redipuglia (1971), which was remodelled in 1995 and is now being remade for the centenary.

Uses

Public perceptions of the ossuaries have an impact on how they are used, which, in turn, influences how they are perceived. After the Second World War there was a decline in official visits by state and other authorities, partly because of an urge to separate Republican interests from the Fascist tradition of large rituals (Dogliani Reference Dogliani1999, 26). That trend was offset in the late 1970s with the establishment of some of the major ossuaries as national monuments, and as venues for state and military ceremonies. In part, the ossuary at Redipuglia is an exception in that it retained an official status across the whole of the postwar period. Situated in eastern Friuli, it became a symbol for italianità, and for the postwar struggles between Italy and Yugoslavia over the contested city of Trieste, which was returned to Italy in 1954 (Fabi Reference Fabi2002, 32–33; Dato Reference Dato2015, 63–78; Antonelli Reference Antonelli2018, 274–280, 283–287). As noted by Gaetano Dato (Reference Dato2015, 51–53), the fact that the ossuary at Redipuglia had been little used by the Fascist regime facilitated its appropriation by the new Republic. Thus, from the 1950s, Redipuglia has acted as a venue for a state ceremony that is held each year on 4 November in memory of the First World War. While that date was used by the Fascist regime to celebrate Italy’s victory in the war, it was integrated into the calendar of Republican Italy as the ‘day of the army’, and of the accomplishment of ‘National Unity’ as defined by the patriotic rhetoric of Liberal Italy (Dogliani Reference Dogliani1999, 24). Although exceptional, Redipuglia is emblematic of how postwar Italian authorities of the Left and the Right have repurposed the ossuaries as political symbols. In an exhibition held in Turin in 1961 to mark the centenary of Italy’s unification, Redipuglia was presented as a patriotic symbol of the conquest of eastern territories (Almagià Reference Almagià1960, 33–38; Owen Reference Owen2010, 404–405).Footnote 4 Speaking at Redipuglia on 4 November 1952, Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi cast the ossuary as a monument to those lost in both world wars. In November 1965, his successor Aldo Moro might be said to have further de-fascistised the ossuaries by associating them with ‘positive’ episodes in Italian history such as the Risorgimento and Resistance. Similarly, in November 1978 the speech given by President Sandro Pertini signalled a successful detachment of Redipuglia from its Fascist past. There is a tendency within such official events to portray the First World War as a just fight for Italian unity. However, postwar narratives that embrace a cult of the fallen reminiscent both of the Risorgimento and of Fascism have evolved to suit the process of de-fascistisation. While retaining a sense of sacrifice, they shift the emphasis from Italy’s war heroes to an indistinct mass of victims of both world wars and of the civil war of 1943–1945.

In their pioneering study of dissonant (or difficult) heritage, J.E. Tunbridge and Gregory Ashworth distinguish between sites of atrocity and victimhood, placing war monuments in the first category because of their associations with perpetrators (Reference Tunbridge and Ashworth1996, 118–120). In contrast, postwar interpretations of the ossuaries point largely to ‘victimhood’. In effect, the fallen of the First World War act as a proxy for the dead of the Second World War and the Resistance – a narrative of ‘expiatory patriotism’ which suggests that the nation’s losses can expiate its guilt with respect to Fascism (Rusconi Reference Rusconi1997, 70; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2008, 229–240; 2010, 252–272).

It should also be noted that not all Italians subscribe to the dominant narratives surrounding the ossuaries. For example, the annual celebrations at Redipuglia have elicited controversy and anti-fascist sentiments (Bregantin and Brienza Reference Bregantin and Brienza2015, 69). Although the ossuaries still serve as ‘preferred stages’ for military rituals, their popularity declined in the 1960s and early 1990s, whether because of their associations with Fascism or their inability to serve immediate political conditions (Antonelli Reference Antonelli2018, xii, 336–338; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2010, 134–148). In addition, while the ossuaries are national monuments, they play a different role as regional memorials, as sources of local pride, or as symbols that express discrepancies between local and national histories. In areas annexed by Italy, they can represent the ‘counter’ memories of those who fought against Italy in the First World War. In 1998, commemorative slabs in the area around the ossuary at Rovereto in Alto Adige/Südtirol were vandalised by advocates for the region’s annexation to Austria, and the names of Austrian dead were painted over those of Italians (Mantovan Reference Mantovan1998). The ossuaries have also played an international role as instruments of foreign diplomacy, and in rituals of reconciliation, as between the Italian and Austrian heads of state at Redipuglia in 1995, and a comparable encounter hosted by Slovenia at the ossuary of Kobarid/Caporetto in 2007 (Fabi Reference Fabi2002, 37; Bull, Clarke, and Deganutti Reference Clarke, Cento Bull and Deganutti2017, 668).

Arguably, the functions of the ossuaries may be relatively subversive or consonant with respect to their origins. In terms of subversion, there have been sporadic efforts to use Redipuglia to illustrate the costs of war, or to transform that ossuary into a monument to peace. In 1950, a project to build an ‘altar of peace’ close to Redipuglia was blocked on the grounds that it would detract from its original character, with the result that the altar was eventually erected elsewhere in Friuli (Fabi Reference Fabi2002, 34; Zehenthofer Reference Zehenthofer2015). Other ceremonies and initiatives that did not involve physical changes have been realised. For example, a local association for the promotion of peace has met at Redipuglia since 1995; and in 2014 Redipuglia hosted a mass for peace that was celebrated by Pope Francis (Fabi Reference Fabi2002, 34; Dato Reference Dato2015, 79–80). That Redipuglia could be associated with peace and harmony, despite its militaristic symbolism, illustrates its versatility – or rather the adaptability of the public mind and its capacity to award different meanings to the same object. However, in national events, patriotic interpretations of the ossuaries have generally overshadowed pacifist impulses. In short, while they remain symbols of national pride and military valour, the symbolic functions attributed to the ossuaries by their creators have been adapted rather than reversed.

Clearly, the manner in which the ossuaries are used and interpreted influences the number and type of visitors that they attract. During the Fascist ventennio, they were visited by veterans, schoolchildren, Fascist leisure organisations, and battlefield tourists. The regime promoted tours of the former frontlines, and awarded the exploration of Italy’s new territories the status of a patriotic mission (Touring Club Italiano Reference Touring Club1929; Bosworth Reference Bosworth1997, 391). After 1945, interest in the ossuaries declined in line with an anti-fascist antipathy to grand ceremonies. In the 1980s, there was a resurgence in battlefield tourism; and while some have been largely forgotten, the major ossuaries now draw considerable numbers of visitors (Dogliani Reference Dogliani1999, 25). Redipuglia attracts an annual average of 420,000 visitors, who are mostly Italian and mainly local – which may reflect the fact that the ossuaries are relatively remote in terms of international tourism. A decrease in the number of veterans has been offset by tourists and military enthusiasts (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Visitors to the ossuary at Redipuglia (author’s photograph 2015).

Similarly, a decline in the number of those who witnessed both world wars and the Fascist period means that the role of the ossuaries as heritage, or as historical monuments, overshadows their capacity to evoke events in living memory, or to act as sites of mourning. The ossuaries also draw school trips, whether as historical artefacts or monuments that can be used to advocate peace.Footnote 5

In effect, there is no single reading of the ossuaries. They have functioned as local, national, and international monuments, and have been clad in various and competing postwar narratives. While remaining primarily associated with the First World War, they have also been linked to the Risorgimento, Fascism, and the Resistance. They have been interpreted as proud symbols of Italian identity, as marking new or occupied territories, as signs of peace or military might, and as sources of tension or national cohesion; hence, the notion of a palimpsest, or a stratification of different memories and interpretations that evolve to suit current conditions.

View from the centenary

The centenary of the First World War reinforced public interest in the ossuaries. While its various initiatives resulted from negotiations between state bodies, local and regional authorities, architects and other interests, the aim of the leading government-appointed committees was to ‘remember the Great War, the heroism and sacrifice of soldiers and of the whole citizenry … as an episode of fundamental importance to the process of building European identity, national history, and cohesion among Italians of every region’.Footnote 6 However, while the centennial commemorations evolved over the period 2014–2018, they were buffeted by major changes in national politics, were polarised and politicised, and restricted in their capacity to reach a mass audience (Labanca Reference Labanca2014, xi-xxxi).Footnote 7 Rather than major national events, the government-appointed committees provided an umbrella for the sponsorship and co-ordination of local initiatives, an approach that limited state expenditure, led to the absence of a major state-sponsored campaign, and offset the need to establish a national, or overarching, narrative (Pergher Reference Pergher2018b, 898).

Since the 1990s, Italy has witnessed a wave of local studies, tours, exhibitions and events relating to the First World War – and a parallel evolution in historiography that has shifted academic interests from the ‘macro’ elements of national history to the ‘micro’ experiences of ordinary soldiers (Pergher Reference Pergher2018b, 881–882). Similarly, in that the centenary was largely shaped by local or civic initiatives, it illustrated the complexity and plurality of collective memories of the war. At the same time, it also embodied the ‘macro’ elements of European integration – which surfaced at Redipuglia in 2014 with a performance of Verdi’s Requiem that was attended by representatives of Italy, Slovenia, Croatia and Austria. Questions regarding the appropriateness of a concert at a Fascist military cemetery were countered by the notion that, as ‘a bridge of peace and friendship’, music might foster ‘cohesion’ among nations.Footnote 8

In general, the centenary helped to maintain a pattern of remembrance whose evolution can be traced back to 1945. It reflected the split between local, national, and international memories, albeit that the local and international layers of the palimpsest surpassed the ‘national layer’ – a fact that also allowed government authorities to avoid an overt confrontation with Italy’s Fascist past, and to navigate the centenary while obviating the need to rewrite established narratives. In short, rather than address the legacy of Fascism, the government sought safety in predominantly local, and also European, narratives.

Nevertheless, the centenary has had both ideological and physical effects. The state is currently funding the restoration of six ‘frontline’ ossuaries at Redipuglia, Monte Grappa, Caporetto, Montello, Oslavia, and Asiago. This is meant to reverse a situation in which the gradual reduction of funding to the commission for the burial of the fallen has left many ossuaries in a state of disrepair. The six projects have been chosen on the basis of their importance in terms of the First World War, the commemoration of the fallen, and their artistic value. The intention is to restore the monuments to their original form, and to create new museum spaces within the ossuaries or nearby buildings. These spaces will be fitted with multimedia and interactive displays illustrating the ‘collective and individual drama of the war using simple and emotionally involving language’; and they will form part of the Memoriale diffuso della Grande Guerra, a national network of exhibition spaces.Footnote 9 The exhibitions are also intended to ‘contextualise the monumental architecture’ of the ossuaries, to educate younger generations with regard to ‘modern, mass and total war’, and to ‘build a future of peace and fraternity among nations’. In official documents, the six projects are meant to promote patriotism, to augment an artistic patrimony, and to yield the economic advantages of tourism.

At a cost of roughly €15 million, the projects have generally met with the approval of the press as timely initiatives that are necessary to the preservation of the ossuaries.Footnote 10 Significantly, however, both press and public documents tend to minimise references to Fascism in favour of the First World War. The historical information provided, in 2015, in relation to the architectural competition for the restoration of Monte Grappa (Figure 2) glosses over the exhumation of the fallen. Although perhaps an unintentional error, it suggests that the ossuary stems from the ‘immediate postwar period’ rather than 1932.Footnote 11 In describing that monument’s relationship to Fascism, the competition brief refers obliquely to the ‘new Italy of the fasces (littorio)’ as the self-proclaimed heir of ancient Rome. Moreover, while recognising that the uniformity of Monte Grappa suppressed the ‘plurality’ of ‘individual memories’ in favour of ‘triumphant imagery’, it promises that a new museum will bring a radical ‘change in perspective’. In fact, the museum will cover ‘the scientific and technological dimension’ of mountain warfare rather than offering political or cultural insights into the past.

A similar brief for the restoration of Asiago mentions the Fascist programme of reburial.Footnote 12 Again, however, the aim of the museum at Asiago is to present modern warfare as a historical and technological event. The documentation stops short of any condemnation of war, perhaps because of the involvement of the military in the proposed project. In contrast, the private museum created in 1990 at Kobarid/Caporetto in Slovenia is explicitly anti-war, and is instrumental in the efforts of the Slovenian government to project an image of a peace-loving nation (Clarke, Bull and Deganutti Reference Clarke, Cento Bull and Deganutti2017, 666–674).

Among centennial plans for the ossuaries, there are also differences between national and regional initiatives. For example, the contribution made by the Veneto region recognises the generative role of the Fascist regime, and its intention to control the memory of the war through the creation of monuments (Comitato Regionale Veneto April 2012). It also acknowledges that attitudes to those monuments in the postwar period were clouded in an ‘evident rhetoric’ – which might suggest that Italy’s involvement with Fascism might be more easily confronted at the level of the region than of the state. However, in the Veneto as elsewhere, the documentation created by local and national authorities for the centenary does not address directly the memory of Fascism, or the Fascist manipulation of the memory of the First World War. Generally, that documentation is in line with the primary objectives of the centenary; namely, to preserve a particular interpretation of the First World War, and to revalorise monuments such as the ossuaries in a manner that downplays their Fascist origins while highlighting their associations with the war.

Contemporary perceptions

In order to understand current attitudes towards the ossuaries it is important to identify institutions, communities and individuals that have been involved with their history. The fact that the ossuaries have been administered by a commission under the Ministry of Defence has influenced how they have been used, altered, and perceived. In 1967, the Italian parliament extended a Fascist-era decree that elevated battlefields of the First World War to the status of national monuments: a strategy that covered, for example, the area around the ossuary at Casteldante Rovereto (Atti Parlamentari, Senato della Repubblica 21 June 1967; Decreto-legge 29 October 1922, n. 1386). As that proposal passed through the Senate, a senator of the Italian Communist Party suggested that responsibility for the ossuaries might be transferred from the Ministry of Defence to the Ministry of Public Education as the ‘best qualified custodian’ for that part of the nation’s ‘historical and artistic patrimony’. Christian Democratic senators opposed this suggestion on the grounds that the ossuaries were not ‘artistic’ monuments, but remnants of war that should remain in the custody of the military. For the Christian Democrats, the ossuaries performed an active role in Italy’s military life, while for a representative of the PCI they were ‘historical monuments’.

For its part, the military commission has consistently described the fallen soldier as its primary concern (Bregantin and Brienza Reference Bregantin and Brienza2015, 95). A publication of 1998 describes the duties of the commission as ‘keeping the memory of the fallen alive’, and ‘remembering war as an objective fact’ (Commissariato Generale Onoranze ai Caduti in Guerra 1998, VII; Bregantin Reference Bregantin2006). That focus on war as an ‘objective fact’ and an inevitable part of national history is also reflected in the museums planned for the centenary. Equally, in terms of the fallen, a recent publication that is co-authored by a member of the commission’s staff affirms that the Fascist authorities, ‘aware of the intense, profound and widespread national feeling’, created the ossuaries in response to the wishes of a grieving population – which might be interpreted as an attempt to afford centennial value to the ossuaries (Bregantin and Brienza Reference Bregantin and Brienza2015, 58).

In its role as custodian, the Ministry of Defence is now flanked by other bodies, including national committees for the centenary, regional, local authorities, and other private and public institutions involved in the restoration projects. Those interests represent a range of different, and sometimes contradictory, positions. For example, at a conference on military cemeteries held in Rome in 2016 under the auspices of the national committee for the centenary, General Rosario Aiosa, as head of the military commission for the burial of the fallen, reiterated that its role was to preserve the memory of the dead.Footnote 13 Similarly, the architect charged with the restoration of the ossuary of Redipuglia, Eugenio Vassallo, affirmed that the aim of that project was to honour the fallen. In contrast, a regional director of the Ministry for Culture, Renata Codello, held that the ossuaries must be preserved, not only for their aesthetic value and historical importance, but also as an ‘admonishment for peace’ (‘monito di pace’). A regional law of Friuli also describes the centenary as ‘supporting the growth of a culture of peace and peaceful coexistence’ – a pacifist agenda that is largely muted in national contributions to the centenary (Legge Regionale, 4 October 2013). These different views illustrate how a delicate consensus has been built around the ossuaries, and between local, military and national authorities. While there is agreement regarding their historical and artistic value, the ossuaries are associated with the commemoration of the fallen, national patriotism, and the promotion of peace. Nevertheless, there is a common narrative in the form of a ‘cosmopolitan’ mode of remembrance that depicts war as an abstract phenomenon with victims, but no culprits (Bull and Hansen Reference Bull and Hansen2015). That emphasis on victimhood is in line with both an Italian rhetoric of ‘expiatory patriotism’ and commemorative strategies promoted by the European Union (Clarke, Bull and Deganutti Reference Clarke, Cento Bull and Deganutti2017, 663). There is also a sense that, in interpreting the First World War as a source of collective memories, the centenary may bridge between the Left and Right in a spirit of national cohesion (Bregantin and Brienza Reference Bregantin and Brienza2015, 98).

Difficult heritage or palimpsest?

On the surface, the ossuaries present a typical case of difficult heritage as sites that were tied to Fascism, and as major and indestructible elements of Italy’s patrimony. Yet, their promotion as part of the centenary suggests that their adoption as heritage has been surprisingly easy. As Joshua Samuels suggests in relation to Fascist remains in Sicily, a perspective that is rooted in the notion of difficult heritage may look for difficulties where they do not exist, or may project problems onto sites that for locals are unproblematic (2015, 122–124). While the concept presupposes a heritage that is consistently ‘difficult’, physical remains are rarely regarded in ‘exclusively negative terms’ (Samuels Reference Samuels2015, 114). Moreover, in focusing on associations with Fascism, this approach may miss the fact that monuments can carry a range of different meanings. Thus, an emphasis on Fascism can be reductive, not only in that it focuses on a specific period, but presupposes that the period in question can be defined simply in terms of inherent difficulties. In addition, the notion that Fascist remains are symbolic of a fixed interpretation of the past may run counter to the fact that the past is always rewritten in the light of current conditions.

The ossuaries are entities whose symbolism is under constant revision. They have carried memories and meanings other than those associated with Fascism. They have been re-used in the postwar period as national monuments, tourist sites, and patriotic symbols. Moreover, their significance in relation to the First World War and the recollection of the fallen has meant that they could not be demolished or forgotten. The commemoration of the nation’s dead is a longstanding tradition of Italian patriotism but, while the ossuaries remain as memorials to the First World War, there has been a measure of ‘selective remembering’ with regard to their Fascist origins. In focusing on the war, it has been possible to promote patriotic traditions over negative associations with Fascism, and to filter a Fascist legacy through an ameliorative history of the war.

That the First World War is considered a safe alternative to a Fascist past indicates the current status of the conflict within the Italian collective memory, and the extent to which perceptions have shifted over the past hundred years. The account of the war that the ossuaries were initially intended to project is markedly different from that which is promoted by the centenary. Under Fascism, the ossuaries endorsed a unifying triumphalism that was meant to silence dissenting voices, and which after 1945 led some critics to point to the Fascist misuse, or misrepresentation, of the realities of the war. Subsequently, speeches made by state leaders at Redipuglia during the 1950s–1970s attempted to use the war to de-fascistise Italian patriotism in favour of Liberal and Republican ideals – and while the avoidance of references to Fascism might be interpreted as evidence of a difficult heritage, it is important to acknowledge the ease with which the ossuaries were integrated into evolving postwar politics that produced fresh versions of the cult of the fallen and developing definitions of patriotism.

The metaphor of the palimpsest accounts for the fact that, even at their inception, the ossuaries reflected differences between the official propaganda of the Fascist regime and local experiences of the First World War. Equally, the centenary demonstrated that such divisions endured in the form of sentiments that were decidedly anti-war, as opposed to the traditional celebrations of heroism and the fatherland. In addition, the ossuaries have been inserted into narratives that were centred, for instance, on regional pride, national unification, and European integration. Images of national unity and patriotic victories have clashed with those of European harmony; and local narratives have tended to eclipse those of the state. Essentially, the ossuaries have been consistently re-coded over time, and shifting energies have added or subtracted, highlighted or diminished, different layers of the palimpsest.

Roberto Escobar has observed a tendency to treat Italian history as a narrative that can be rewritten – a tendency that has been facilitated by a lack of consensus (Reference Escobar2003, 348). Thus, it is possible to obscure the Fascist layer of the palimpsest under other historical references; and where associations with Fascism might persist, they might also be diminished or transformed. While these complex revisions illustrate the potential shortcomings of an approach that treats Fascist monuments as a difficult heritage, the ossuaries are by no means unique as monuments with ‘alternative identities’. The remnants of Fascism have been reinterpreted over time, as meanings generated by their creators were replaced by subsequent generations, or became redundant in the face of shifting political and social values. Thus, the notion of the palimpsest might be extended to other Fascist monuments given that all have taken on new and adjusted meanings since 1945.

Conclusion

While they originally functioned as elements of Fascist propaganda, the ossuaries have been put to new political and cultural uses; most recently for the centenary of the First World War. In today’s Republic, as in Fascist Italy, the ossuaries are used to articulate perceptions of the past, and to carry memories that are suited to immediate political and social conditions. In general, postwar narratives have emphasised relationships between the ossuaries, the First World War, and the fallen, while downplaying associations with Fascism. Current agendas promote sentiments that range between patriotism and pacifism, and which vary between local, national, and international contexts. They also reflect a reformed approach to the cult of the dead, which combines a national narrative of expiatory patriotism with a European emphasis on the victims of war. The flexibility offered by shifting memories has allowed the ossuaries to be repurposed as national monuments that commemorate war and its victims while promoting patriotic sentiments that bolster the identity of Republican Italy. Perhaps at some point in their future the ossuaries might become the subject of a programme of ‘critical preservation’ – that is, they might represent a more comprehensive coverage of their Fascist origins and of Italy’s history (Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2000, 279; Carter and Martin Reference Carter and Martin2017, 355–356; Hökerberg Reference Hökerberg2017, 771–772). Once opened, the new museums may foster a more developed and constructive discourse, and may exchange a process of selective remembering for one of national introspection. On the other hand, it is clear, given their history since 1945, that the ossuaries will always carry memories that are evolving, pluralistic, and divided. That ongoing process of revision presents a major challenge to a perception of the ossuaries as difficult heritage; mainly, because that perception overlooks the multiplicity of associations that can be attributed to monuments, and the manner in which associations can be rewritten. In contrast, the notion of a palimpsest can account for divided histories, and for memories that are coined to suit immediate needs. It can explain the complex ways in which the past can be concealed, or amended in favour of competing historical narratives. It can also be used to demonstrate that there is no ‘easy access’ to an understanding of the Fascist legacy; and no way to escape the plurality and flexibility of the collective memory.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank for their essential suggestions the editors, Nick Carter and Simon Martin, and the anonymous reviewers. I am indebted to Samantha Owen for generously sharing a source. I am also grateful to Oliver Janz and his group at the Freie Unversität Berlin for providing the ideal intellectual environment for research on the First World War and its legacy.

Hannah Malone is an architectural historian interested in politics and death. As a Humboldt Fellow at the Freie Universität in Berlin, she is currently writing a book on Italy’s Fascist ossuaries of the First World War. Her first monograph, Architecture, Death and Nationhood: Italy’s Monumental Cemeteries of the Nineteenth Century, was published by Routledge in 2017. Her next project will compare the treatment of Fascist and Nazi architecture in postwar Italy and Germany.