My first experience with the Impact of Materials on Society (IMOS) course came after meeting with University of Florida Professor Kevin Jones and MRS Outreach Coordinator Pamela Hupp at the Public Outreach Booth during the 2016 MRS Spring Meeting & Exhibit in Phoenix. The IMOS course originated at the University of Florida from the desire to help engineering students understand why humanities and sociology classes are relevant by showing their connections to engineering and helping to expose non-engineers to what engineering is about. We had a long discussion about the inception, aims, and implementation of the course with freshmen students at the University of Florida. I was particularly intrigued by the interdisciplinary approach to materials education and the collaboration between an engineer and a social scientist in preparing and delivering the course modules.

My role at that time was as an Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) coordinator and teacher trainer. I was in search of opportunities to develop educational resources and training sessions that would be meaningful to the teachers and students and that would combine environmental, social, and economic aspects. The IMOS course looked like a promising candidate, so I wanted to learn more about it. The opportunity came when I participated in the IMOS workshop during the 2016 MRS Fall Meeting in Boston. During the IMOS workshop, I trained with an international group of enthusiastic educators from universities and community colleges. I discovered I was the only person representing the secondary education sector, so I started considering the idea of adapting the course for secondary school implementation, although I could foresee some challenges. First, the course was originally designed for university students with more advanced knowledge about the subject than secondary school students, and the content was in English, so it had to be translated. Second, there was no guarantee it would match the Greek secondary education curriculum and be applicable to Greek standards.

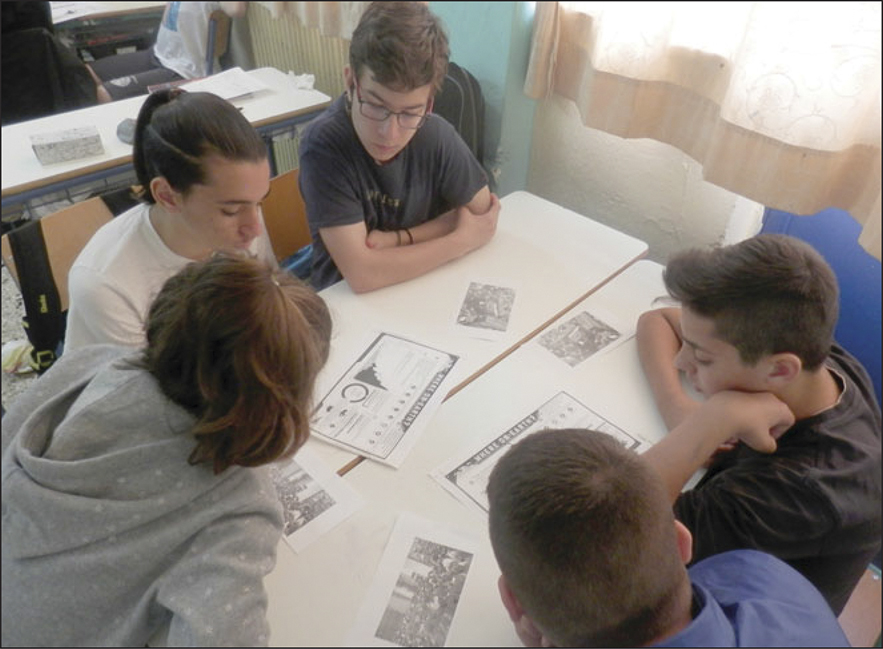

Above: Science teachers discuss the journey of e-waste in developing countries during the training seminar. Below: High-school students working in groups to prepare their tanglegrams about electronic devices.

Initially, I was concerned that the task would be too overwhelming, but after cautious reflection on the course’s modules and discussions with teachers from the school district of Piraeus in Athens, I redefined the aim of my endeavor to adapt the IMOS course for use in Greece. Then the idea of a connecting story was formed. The connecting story had to refer to something relevant to the students’ and teachers’ lives that would raise their interest. Mobile phones and electronic devices, in general, are part and parcel of most people’s lives. But only a few people think of the material base underlying the innovative functions of mobile phones, and how their consumer and disposal choices affect the lives of people in distant countries and also the environment.

Sustainability challenges are complex and interconnect many people, things, and processes in the social, environmental, and economic realms. Electronic devices also contain rare-earth elements that are only marginally incorporated into the Greek secondary school curriculum. With the idea of a connecting story came the determination to select the IMOS modules that could support the narrative of the educational material, would reveal all the aspects of their life cycle, and enable productive interactions between teachers and students that would lead to action. The course elements that would help teachers and students acquire new knowledge, visualize complexity, and take action were the Rare Earth Elements video and lecture and the entanglement activity from “Module 2: Clay,” the creative destruction activity from “Module 8: Iron and Steel,” and the polymers in-class activity from “Module 11: Plastic.”

After that, the educational material was assembled and contained the following sections:

1. Interest raising section—How is black Friday connected to consumerism and globalization?

2. Teachers/students articulate opinions and reflect critically on their relationship with mobile phones.

3. Teachers/students complete a questionnaire about mobile phone use and disposal.

4. Introduction to Rare Earth Elements video/lecture and infographic.

5. Life-cycle assessment of electronic devices (environmental, economic, and social impact).

6. Mapping complexity: Entanglement with electronics (How are people, things, and processes entangled in the electronics sector?).

7. Introduction to planned obsolescence—Reflection on natural resources depletion and waste problems.

8. Introduction to alternative economic models—circular economy.

9. Role-playing activity about social resistance and cautiousness to change.

10. E-waste problem overview—Why developing countries become the rubbish dumps of developed countries?

11. Teachers and students become the designers of the green mobile phone of the future and pitch it in front of investors.

Finally, they would give their feedback.

The educational material was discussed with the school advisors of the district of Piraeus in order to identify the best approach to implement the teacher training sessions. Collaboration between us was created so the training seminars would last about three hours and take place during the in-service training time slots available. This was important to ensure wide participation of science teachers in the seminars. The first task was to make sure that the announcement of the training seminars would reach a significant number of middle schools and high schools and attract the interest of physics, chemistry, biology, earth sciences, and other relevant discipline teachers. This was achieved through careful planning. During the two sessions, more than 50 teachers participated.

Middle-school students studying an infographic about the properties, applications, and environmental and socioeconomic impact of rare-earth elements.

The second task was to identify the appropriate places for the seminars. The selection came naturally, as there are two well-known science centers that support science teacher training in Piraeus. Teachers and trainers who participated were enthusiastic because of the experiential nature of the training. They worked in groups and had insightful discussions throughout the activities. They expressed strong views about the potential of increased personal and collective responsibility in bringing positive change in the society. As one teacher said, “it is the current economic model of incessant growth that deteriorates the state of the planet, robs it of resources, and jeopardizes our future! We have to break the current cycle of consumption and come up with more creative solutions.” Teacher’s tanglegrams showed the interconnections of materials, people, and processes and revealed the complexity of the life cycle of electronics, and collectively (all the groups together) revealed the bigger picture of interdependencies and cause and effect relationships at play. Moreover, they identified connections between distinct parts of the system in focus and expressed them as loops.

During the role-playing activity, the teachers were given the following story: “An engineer manufactures an everlasting thread and is very happy about the invention! How do the following stakeholders react to the news? Factory owner who designs old-type fibers, factory workers, politician, consumers, and representative of an environmental organization. The engineer also supports their opinion with arguments.” As one of the teachers commented, “This activity gave voice to our thoughts and helped us unfold our argumentation capabilities.” The final activity about designing the mobile phone of the future gave them the opportunity to talk about advances in the field of materials science, and how they could use them in creative ways to envision the development of environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable devices.

At the end of the teacher training sessions, lively discussions were held about the implementation of this educational material with school students. The teachers suggested there were some possibilities of using it to support the course “Natural Resources Management” in high schools or during project courses and environmental education programs in middle and high schools.

Some of the teachers expressed interest in implementing this educational material at their schools. The second phase of the project has just started. To obtain evidence from both levels of secondary education and from applications on different types of courses, two school implementations were scheduled. The first implementation group consisted of high-school students (aged 16) attending the “Natural Resources Management” course, and the second group was middle-school students (aged 14) attending an Environmental Education program. The main obstacle was finding time to implement it at school, as the educational material needs four consecutive teaching hours to be completed (each one lasts 45 minutes) and could possibly disrupt the school program. However, with careful planning, everything ran smoothly. The course with the high-school students had very positive results, as students immediately engaged with the subject. Some of them said, “it is the first time that we actually perceived our mobile phones as an educational medium, instead of something we are not allowed to bring in the classroom.” Students produced tanglegrams, which although were simpler than those of the teachers, showed they are active systems thinkers capable of perceiving cause and effect relationships. One student at the end of the intervention asked, “What can we do with all the mobile phone devices we keep in drawers in our homes? How can we reuse their precious materials without negatively influencing the lives of people in underdeveloped countries? Are there recycling companies that undertake this process in a socially responsible manner?”

After the success of conducting the high-school course, we had the challenge of adapting it for middle-school students, who may struggle with some of the concepts. However, by using simple language and videos suitable for eighth graders, they were able to deeply engage in the activities. The teacher noticed some of the students who rarely participated in classroom discussions gained confidence and expressed their opinions openly without reservation. Another student mentioned, “Perhaps the responsibility of sustainable production, consumption, and disposal of electronics lies not only with the individuals, but also with the corporations that are involved in the process,” but “nonetheless, my mobile phone device will never look the same to me now that I know the story behind it.” At the end of the session, some of the students were likely to discuss starting a campaign at their school to collect unused or damaged mobile phones for recycling and give them to companies that could disassemble and recycle them in Greece.

By the end of the school year 2016–2017, 56% of the teachers who participated in the two training seminars said they had used all or part of the educational material in their classrooms. Some suggested that this material could be used to measure knowledge and attitude change in students by asking them to complete the “designing the green mobile phone of the future” activity at the beginning and end of the educational intervention to compare the outcomes. An assessment metric was then created for this activity.

An unanticipated result of my involvement in the IMOS course and the positive experience of taking it to Greek schools was my decision to pursue a PhD in assessing students’ systems of thinking and behavioral change for more sustainable lifestyles. One of the most important moments in this journey was when I was invited to present this effort during the Education Symposium at the 2017 MRS Fall Meeting, which was received with enthusiasm and enabled me to forge strong collaborations with various educational institutes around the world. The results of this work are published in the MRS Advances journal (https://doi.org/10.1557/adv.2018.64), where interested readers can find more details about the educational material and implementation outcomes.