Article contents

Global Economic Outlook Inflation prompts policy normalisation

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2022

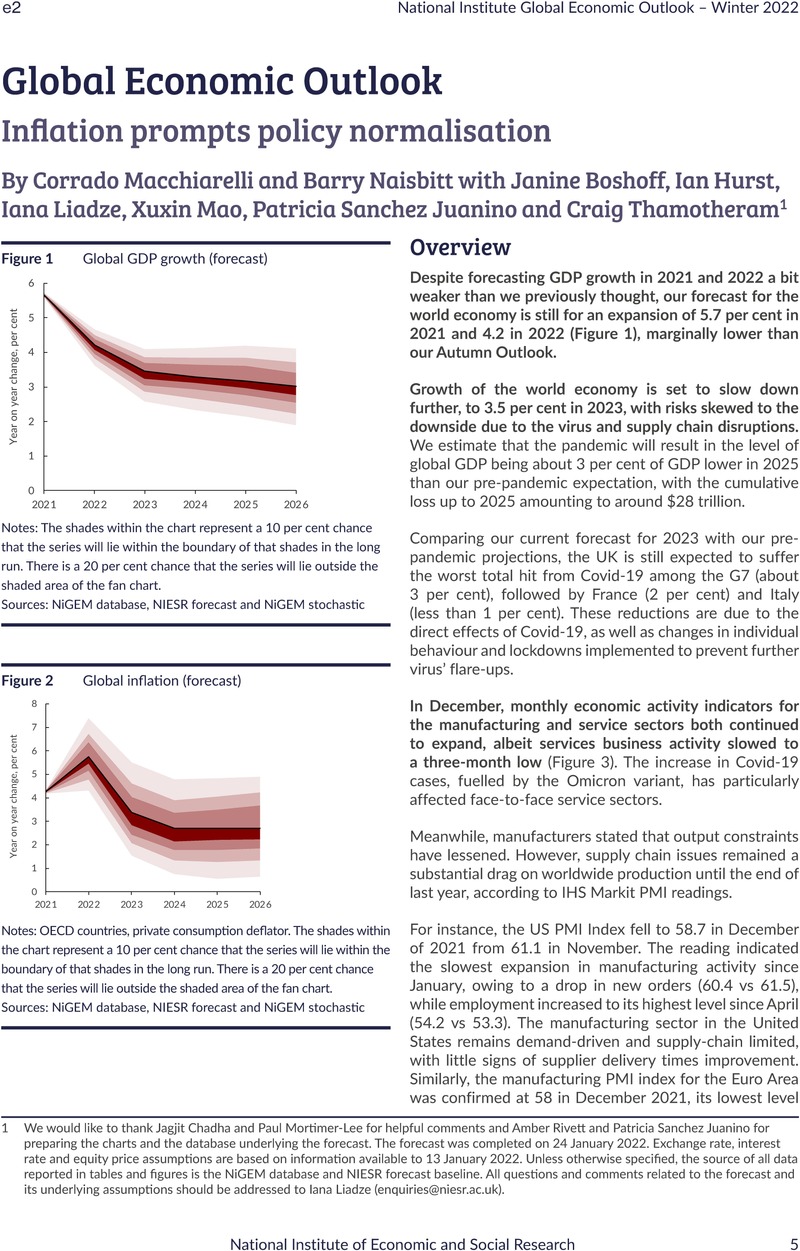

Abstract

- Type

- World Forecast

- Information

- National Institute Economic Review , Volume 259: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF POPULISM , Winter 2022 , e2

- Creative Commons

- This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Copyright

- © The Author(s), 2022. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of National Institute Economic Review

Footnotes

We would like to thank Jagjit Chadha and Paul Mortimer-Lee for helpful comments and Amber Rivett and Patricia Sanchez Juanino for preparing the charts and the database underlying the forecast. The forecast was completed on 24 January 2022. Exchange rate, interest rate and equity price assumptions are based on information available to 13 January 2022. Unless otherwise specified, the source of all data reported in tables and figures is the NiGEM database and NIESR forecast baseline. All questions and comments related to the forecast and its underlying assumptions should be addressed to Iana Liadze (enquiries@niesr.ac.uk).

References

- 4

- Cited by