Introduction

The crises that shook Europe in recent decades—whether the financial crisis, the war in Ukraine, Brexit, or the crises surrounding the arrival of refugees and the Schengen zone—have resulted in a changing paradigm in public discourse on the subject of borders. The imaginaries of a borderless world and the end of the nation state (Ohmae Reference Opiłowska2008) that were the focus of academic as well as public debates after the fall of the Iron Curtain, have thus been replaced by rebordering politics, new border regimes, reframing of borders into more complex categories, and in some cases, the revival of nationalist discourses. As some scholars have argued, the Schengen crisis in 2015 revealed the end of the “myth” of a Europe without borders, as it exposed how political and administrative borders had never truly disappeared (Wassenberg Reference Watkins2020, 36). However, even before a performance of the mentioned myth was limited rather to the internal borders of the European Union (EU) and security concerns revealed the political demands for more restrictive border regimes (Scott, Celata, and Coletti Reference Strüver2019). The recent crisis at the Polish-Belarusian border and the plan of Polish government to build a wall there to prevent the illegal border crossings exemplify the increasing controlling border orientation of states (cf. Kenwick and Simmons Reference Klatt2020). In contrast to the ethos of globalization, as Victor Conrad claims, “which promised access with mobility, nation-states and various agents of authority have engaged reactionary borders and bordering to retain power and control” (Konrad Reference Nossem2021, 6).

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 challenged the imaginary of Europe without (Pinos et. al. Reference Pinos and Radil2020) borders even more sharply by breaking with the “normality” of Schengen rules impeding cross-border flows of European residents (Wille and Weber Reference Zenderowski2021), and revealing the primacy of nation-states and reinforcing nationalist dynamics (Bieber Reference Bieber2022). It caused, as Hynek Böhm argues, an advent of unilateralism: “The central state returned as a key and often only actor in the public space” (Böhm Reference Böhm2021, 2). Eva Nossem points out that we can observe “nationalism of pandemics” illustrated by introduction of national/local responses to the health crisis and supplying the treatment for own populations, and by “numerous attempts of apportioning blame and (racist) finger pointing toward other states for their presumed errors in fighting the pandemic” (Nossem Reference Ohmae, Lechner and Boli2020, 5). Hence, nation states not only responded to COVID-19 with external border restrictions and border controls, but also with rhetorical bordering as many state leaders speculated “about the foreign origin of the virus, often in derogatory terms” (Kenwick and Simmons Reference Klatt2020, E41).

These new conditions and challenges ultimately pushed borders and borderlands to the forefront of public and academic attention (Klatt Reference Konrad2020; Wille and Kanesu, Reference Wille, Weber, Mein and Pause2020; Wille and Weber Reference Zenderowski2021).

It is noteworthy that the decisions to contain the pandemic—through the bordering politics—radically altered everyday life for many inhabitants in the border region (Opiłowska Reference Opiłowska and Roose2021). These constraints triggered various reactions from borderland actors and communities, which will be analyzed further here.

Borderlands are spaces where different imaginaries surrounding borders come into sharp focus: on the one hand, grand imaginaries of a global borderless world, an integrated Europe without borders, or conversely, nation states and nationalism as the sole guarantors of security; and on the other hand, smaller imaginaries of borders as a resource, or as a barrier. Thus, the (non)existence of borders influences local politics, opportunities for cross-border cooperation, and the everyday lives of its nearest inhabitants. Divided cities are thus seen as laboratories of European integration: because of their geographical location, they are the first to experience the positive or negative effects of integration (Schultz Reference Scott, Celata and Coletti2005; Opiłowska and Roose Reference Pinos and Radil2015). This article focuses on two twin towns: one located on the Polish-German (Słubice-Frankfurt/Oder) and the other on the Polish-Czech (Cieszyn-Český Těšín) border. In both cases, political decisions (in 1945 and 1920, respectively) caused cities to be divided between two states and forced them to function with a closed border for years. Although cross-border cooperation was developed during the communist period and the border was open to non-visa and non-passport traffic between 1972 and 1980, cross-border contacts were mostly limited to ideologically controlled and closely monitored events. Thus, they could not effectively contribute to the integration of border communities.

Since the 1990s, and in particular since Poland and the Czech Republic joined the EU (2004) and the Schengen Agreement (2007), cross-border cooperation developed and intensified. Despite the similarities shared by both twin towns, as aforementioned belonging to the EU; the specific border location, or the historical legacy of division, the analyzed cases can be also characterized by structural, cultural, or economic (a)symmetries shaping cross-border relations (Dołzbłasz and Raczyk Reference Dołzbłasz and Raczyk2015; Castañer, Jańczak, and Martín-Uceda Reference Castañer, Jańczak and Martín-Uceda2018). It is worth to mention that both cases belong to the group of border twin towns being ‘integration forerunners’, joining old and new EU member states and located on borders with conflict legacy (Jańczak Reference Kasperek and Olszewski2013, 96), but while the Polish-German town refers rather to European integration, the Polish-Czech case is more embedded in the framework of regional cooperation. The difference may result from the historical legacy. In both cases, twinning can be regarded as a tool to overcome historical conflicts; however, whereas in the Polish-Czech case the conflict had rather a regional dimension (over Cieszyn Silesia), the German-Polish bilateral relations were shaped by mutual enmity and the tragedy of two world wars for centuries. It should be noted that, although both Polish towns seem to benefit more from the open borders at least regarding the labor market, the Polish-Czech pair is less imbalanced in the case of the estimated GDP per capita (Decoville, Durand, and Feltgen Reference Dolińska, Makaro and Niedźwiecka-Iwańczak2015).

Despite the differences in both twin towns transnational practices (work, education, shopping) became embedded in everydayness (Zenderowski Reference Zenderowski2002; Dolińska, Makaro, and Niedźwiecka-Iwańczak Reference Hreczuk2018). Hence, the decision of state authorities to close the borders in 2020 was a shock for many residents and has triggered numerous reactions, including protests and solidarity acts.

Against this backdrop, the aim of the article is to analyze the discursive reactions to the border closures in Słubice-Frankfurt/Oder and Cieszyn-Český Těšín in the first stage of the closed borders (March-May 2020) and elaborate on the imaginaries to be found there in comparative perspective. The first section discusses the theoretical framework by focusing on the notions of borders, transnational borderscapes, and imaginaries. The second part introduces this study’s methodological underpinnings, based on a discursive historical approach (DHA), followed by a short description of the context of twin towns during the pandemic. Subsequently, we apply the DHA approach to explore the discourse and imaginaries on borders in the selected case studies. Finally, we compare and summarize the main outcomes of our empirical inquiry in the concluding part.

Theoretical Framework

In recent decades, the function of borders and their conceptualization in the scholarly literature and in public debates has shifted, as the notion of borders as a particular line in a particular space has transformed into a growing understanding of borders as processes, complex institutions, practices, and discourses (Wille Reference Wille and Kanesu2021). As Anne Amilhat-Szary (Reference Amilhat-Szary, Agnew, Mamadouh, Secor and Sharp2015, 14) argues the renewal of border studies in the 1990s was based on the shifting of boundaries toward critical studies that were questioning “the linear component of spatial divides.” Similarly, globalization processes—associated with flow, fluidity, deterritorialization, and networks—are determined by the porosity of borders. A border “has become one of the dominant spatio-legal metaphors of contemporary politics, either in their purported disappearance, rearticulation, or surprising persistence” (Salter Reference Schultz2010). Thus, borders are essential for social relations by making a difference between “us” vs. “them,” by regulating inclusion and exclusion, and thus, offering the answers who belongs to (ethnic, national) community and who is a stranger. Moreover, borders are key institutions within sovereign nation-states, as they bound territory, limit the space of law, political authority, responsibility, and regulate economic relations through taxes and duties. Through borders, the global mobility regime is structured by tools, such as passports, visas, and the ideology of citizenship, that are examined at the border (Salter Reference Schultz2010, 515–517).

According to Étienne Balibar (Reference Balibar2002), there are three aspects of the equivocal character of borders: overdetermination (they are impacted by political, economic, social, cultural, and linguistic factors), polysemy (they never “exist in the same way for individuals belonging to different social groups”) and heterogeneity (borders fulfil various functions simultaneously). The complex and diverse character of borders is noticed also by Anne Amilhat-Szary (Reference Amilhat-Szary, Agnew, Mamadouh, Secor and Sharp2015, 6), who points to the dialectical character of borders as they simultaneously undergo debordering and rebordering processes by opening up to let pass increased flows of people, goods, capital, and ideas, and by closing down for the purpose of providing security by controlling and filtering those flows.

To grasp the comprehensive nature of borders, the notion of borderscapes was introduced to mark the shift between understanding borders as territorial dividing lines and the notion of borders as socio-cultural and discursive processes and practices that arose from the need “to problematise the border not as a taken-for-granted entity, but as a site of investigation, by exploring alternative border imaginaries ‘beyond the line’” (Brambilla Reference Brambilla2015, 17). This concept allows, as Brambilla and Jones (Reference Brambilla and Jones2020, 289) argue, for a consideration of “the complexity of border processes as variously created, experienced, and contested by human beings.” Hence, the borderscape notion “provides a political insight into critical border studies that further problematizes the complexity of borders by accounting for the multiple dynamics of power that are involved in the border, which is reinterpreted not only as a site of the production of sovereign power but also of resistances and struggles” (Brambilla and Jones Reference Brambilla and Jones2020, 289).

Within such a perspective, our study is particularly focused on transnational borderscapes as representations of borders as discursive landscapes that highlight borders as both symbolic and material constructions arising from discourses, practices, and social relations. Thus, two particular aspects are addressed: first, the multiple forms of border experiences that mark the lives of individuals residing nearby and that often clash with official political rhetoric and state policies, and second, border representations in discourses. That being said, we are focused here not on the “big stories” of nation-state construction or European integration, but predominately on the “small stories” that arise from everyday border experiences and reveal hidden or silenced borders (Brambilla Reference Brambilla2015, 20–28). Anke Strüver (Reference Sum and Jessop2005, 2) emphasizes that narratives, images, imaginations about the respective “other side” influence the crossings and non-crossings of borders, allowing for an analysis of border discourse and imaginaries that reveals the reasons behind (in-)effective cross-border cooperation. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that borders are not only imaginary structures, but also real institutions—although not with a fixed function and status, still characterized by an ambivalence that “institutionally represents both closeness and aperture, or their permanent dialectical interplay” (Balibar Reference Balibar2010, 315–316).

In addition to the notion of borderscape, the concept of imaginaries is also significant for our study that was developed within borderland studies by Hans Joachim Bürkner, who states that “by analyzing how imaginaries are implemented and utilized within various types of discourse, it is possible to reconstruct the ideational shaping of borders, in particular in connection to bordering and the arranging of borderscapes” (Bürkner Reference Bürkner, Opiłowska, Kurcz and Roose2017, 94). The concept of imaginaries, initially borrowed by Bürkner from post-structural political economy (PSPE), is defined here as “the theoretical link between the everyday and multi-scalar power relations” (Bürkner Reference Bürkner2015, 28–29), which fills the void left by social constructivism and involves taking into account different dimensions of social practice, including politics and economy. Furthermore, the notion of imaginaries, similar to many other concepts used in social sciences, has been defined in different ways. For instance, there are studies on social (Taylor Reference Wassenberg2004), political, economic (Sum and Jessop Reference Taylor2013), and spatial imaginaries (Watkins Reference Wille, Gerst, Klessmann and Krämer2015; Scott et al. Reference Strüver2019), located within different theoretical approaches. Based on Benedict Anderson’s concept of imagined communities, Charles Taylor considers social imaginaries from the perspective of rather general categories, such as “the ways people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images that underlie these expectations” (Taylor Reference Wassenberg2004, 23). A further development of the concept demonstrates that imaginaries can also be seen as sets of “basic ideas, images, symbols, and emotions tied to political projects” (Bürkner Reference Bürkner2015, 29) often derived from both broader ideologies, the ways in which institutions are organized and structured, and people’s ideas how it should be. Although imaginaries depend on political, economic, and social interests, the implementation of a semiotic approach allows for a more complex picture to emerge of the semiotic and extra-semiotic processes inherent to these imaginaries. As Ngai-Ling Sum and Bob Jessop state, “semiosis and imaginary are closely related, but not identical” as semiosis refers to the social production of intersubjective meaning, while an imaginary denotes both semiosis as well as extra-semiotic—material—practices (Sum and Jessop Reference Taylor2013, 165). Imaginaries can thus be understood as “semiotic systems that frame individual subjects” lived experience of an inordinately complex world and/or inform collective calculation about that world’ (Sum and Jessop Reference Taylor2013, 165).

Importantly, social imaginaries have a collective element: they are shared by large groups of people and thus generate a “common understanding that makes possible common practices and a widely shared sense of legitimacy” (Taylor Reference Wassenberg2004, 23). Hence, they are also vital for the actions of collective actors as a point of reference and guidance for their decisions. Both stakeholders and ordinary people, equipped with various resources, can construct different imaginaries, as well as refer to larger (sometimes contradictory) imaginaries, adjusting them to local contexts to help legitimize their views or promote their decisions and actions (Bürkner Reference Bürkner2015). Against this backdrop, imaginaries play a strategic role in the transmission and reproduction of power. As various imaginaries do compete against each other, it becomes important for different actors to strategically relate the visions and projects to given imaginaries to increase their influence (Sum and Jessop Reference Taylor2013).

In terms of the implementation of imaginaries within a border studies framework, Bürkner is most interested in social imaginaries, which “refer to the ways in which social relations, the condition of a society, the relations to nation states or the world society is imagined,” and spatial imaginaries, which “relate to geopolitics or economic restructuring; they address basic ideas about the shape of territories, the ‘natural’ relationship between societies or nations to territories, the way boundaries and borders are drawn, and processes of regionalization” (Bürkner Reference Bürkner, Opiłowska, Kurcz and Roose2017, 93–94). As such, spatial imaginaries can operate in a variety of spaces: from the very local to the supranational and global (Watkins Reference Wille, Gerst, Klessmann and Krämer2015), and—similarly to social imaginaries—they are collective and shared by a large number of people. Moreover, they can be interlinked and mutually dependent, as in the case of the imaginaries of globalization, a borderless world, and a Europe without borders. One of Bürkner’s important contributions is the development of a model of imaginaries (Bürkner Reference Bürkner2014, 7), wherein he distinguishes between big and small imaginaries, where the latter can be related to the former, but are ‘accommodated’ and more context-based. For example, the notion of a town divided by a border as singular transnational organism can constitute a small spatial imaginary which refers back to various larger imaginaries, such as that of a world of open borders or borderless world (Paasi Reference Paasi, Paasi, Prokkola, Saarinen and Zimmerbauer2019, 30–31). At the same time, such a transnational imaginary may clash with counter-imaginary of state borders as means to protect territory and ethnic-national community. And indeed, many governments resorted to border restriction rather than implementing domestic mitigation procedures. Thus, as Kenwick and Simmons point out, “the pervasive use of external border controls in the face of the coronavirus reflects growing anxieties about border security in the modern international system” (Kenwick and Simmons Reference Klatt2020, 1).

Furthermore, Bürkner argues that imaginaries participate in the development of both political projects (residing in the public sphere and exposed to multi-level competition) and personal projects (focused on personal living conditions). Considering that crises often create more favorable conditions for changes in bigger imaginaries (Sum and Jessop Reference Taylor2013), it can be assumed that the border closure may have caused certain existing imaginaries to be strategically used by individuals in their personal projects to justify their claims and needs, subsequently allowing new imaginaries to possibly emerge—what we are going to explore in the empirical section.

Methodological Approach

As elaborated in the theoretical section, by exploring discourse surrounding the closure of borders in response to COVID-19, it becomes possible to focus on and compare shifts in the imaginaries of two particular twin towns. Considering the variety of approaches to discourse analysis, it is vital to clearly define the research frameworks implemented here.

As imaginary is understood here in a broader sense—as a set of “basic ideas, images, imaginations, symbols and sentiments” (Bürkner Reference Bürkner2014, 4) tied to both the past, present, and future management of borders and the ways people imagine they should be organized—our analysis is focused on the discursive strategies used in the creation of various (non)border imaginaries. A discourse is comprehended here—according to the discourse-historical approach (DHA) —as “a cluster of context-dependent semiotic practices that are situated within specific fields of social actions” (Reisigl and Wodak Reference Salter and Turner2016, 27). This DHA is based on the principle of triangulation, which aims to minimize the risk of a researcher being too subjective by using multiple theories, methods, data, and background information to enable a full understanding of the complexity of the phenomena under study. Moreover, there is also a need to take into account different levels of analysis, including language and the broader socio-political and historical context (Reisigl and Wodak Reference Salter and Turner2016, 30–31).

As such, it is crucial to not simply focus on particular texts (official documents, political statements, news articles, social media posts, and comments), but to also consider their context, as well as the broader context in which they were produced. In the present analysis, the socio-political context of the pandemic and political decisions occurring in response to it is of primary importance, although other possible contexts within divided towns, including historical ones, also remain relevant to understanding and explaining the discursive strategies reflected in the analyzed texts. This study aims to reveal what kind of imaginaries (bottom-up, top-down, universal, and local-based) and argumentations appear in the statements produced by different actors.

As the analysis concerns the discursive strategies (Reisigl and Wodak Reference Salter and Turner2016, 32) about how (non)border imaginaries are (re)created and told in the case of twin towns, we decided on four main lines of inquiry:

-

1. How are borders and rebordering process named and described by different actors?

-

2. What arguments (counterarguments) are used by these actors and how do they justify their positions?

-

3. What imaginaries can be distinguished from within the discourse?

-

4. What stances do these actors represent in the discourse? From what point of view are their arguments expressed?

As the analysis is comparative in its intent, while exploring the above questions, we also aim to identify similarities and differences between both twin towns. Since the discourse on border closures is realized through a range of texts produced locally by various actors on the borderlands who present different (sometimes contrary) lines of argumentation, the analysis focuses on available materials to distinguish the various discursive strands, namely: (a) petitions and appeals published by local politicians and residents, 3 entries; (b) posts and comments on Facebook city profiles, where the border situation was discussed (Cieszyn i Śląsk Cieszyński: cieszy.pl [no. of entries: 19]; Město Český Těšín [6] entries; Nasze Słubice.pl [42]; Frankfurt und Słubice: Doppelt schön [16]); (c) selected media outlets reporting on the situation in the borderlands (Gazetacodzienna - Śląsk Cieszyński on-line [8]; Karvinský a Havířovský deník, [3]; Märkische Oderzeitung [6]; Oderwelle [1]; Gazeta Lubuska, [4] and Gazeta Wyborcza. Oddział Zielona Góra [1]; and (d) statements and interviews with local political and cultural elites commenting on the situation (Cieszyn [4]; Český Těšín [1]; Słubice [3]; and Frankfurt/Oder [2]). A sampling of the materials was preceded by preliminary desk research for sources that discussed the issue systematically and comprehensively. However, we are aware that, in the case of social media sources, we can only assume that the commentators live in the analyzed towns. The analysis captured the most dynamic period, starting with the border closures and including three individual weekend protests held between 15 March and 12 May, 2020. The scope of our analysis is local, making a bottom-up perspective and focus on the voices of individuals and collectives involved in the new border context imperative. Nevertheless, we assume that supra-national and national-level imaginaries, which we also aim to detect and explore, are reflected in the local discourse. The analysis was conducted with Atlas.ti software.

Twin Towns in the Shadow of a Pandemic

The COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated that divided towns can be treated as laboratories for processes of de- and rebordering. In Poland, Czech Republic, and Germany, borders were temporary closed in the middle of March 2020, affecting everyday cross-border practices, such as working, visiting family and friends, shopping, or accessing medical care on the other side of the border. Thus, the decision to close the border had a enormous impact on borderlanders. Initially, cross-border commuters were able to continue crossing the border on daily basis, but on 27 March, the Polish government introduced a mandatory 14-day home quarantine for all people entering Poland, including cross-border workers. As a result, employees were forced to decide whether to stay abroad until a change in government policy or to stay home, not working. Even though Germany and the Czech Republic allowed border crossings for professional reasons, Polish workers found themselves in a “territorial trap” (Agnew Reference Agnew1994). For most workers (apart from health and social care workers), the rules were loosened by the beginning of May, for all others by the middle of May. However, although the border was already open in other parts of Poland and Czech Republic, it was still closed in the Cieszyn Silesia area where Polish-Czech twin town is located, until June 29. Moreover, Czech regulations required a negative COVID-19 test to cross the Polish-Czech border until August 14.

In the case of both analyzed twin towns, governmental decisions prompted three kinds of reactions. First, performative initiatives expressed a longing for a neighbor—the city and its inhabitants on the other side of the border. Initially, representatives of the Cieszyn cross-border cultural institution hung a banner (I miss you, Czech!) on the riverbank, and inhabitants of the other side responded in kind. Moreover, Polish and Czech musicians, inspired by the banners, recorded a song dedicated to the towns. Similar messages appeared in Frankfurt/Oder and Słubice on the bridge connecting the two towns. Second, petitions and appeals were directed to the Polish government by inhabitants and local politicians. Third, three weekend protests (April 24–25, May 3–4, May 9–10) were held, at which people gathered and expressed their demands, especially in response to the situation of cross-border workers and their families. In Cieszyn and Český Těšín, they were promoted as “walks against the border” under the main slogan “Open the border!,” and “Let us work, let us [go] home!” in the case of Słubice and Frankfurt/Oder. The protest’s main demands remained centered on cross-border workers’ situation. Some had lost jobs due to pandemic regulations; some were forced to stay across the border, causing dramatic family- and work-related issues.

The (Un)wanted Revival of Borders: Between Calling for Normalcy and Calling for Safety

Our analysis distinguished four main discourse strands that applied normative as well as (dominant) pragmatic argumentation strategies. However, whereas they demonstrate both opponents and supporters of border politics, the vast majority of the population in 12 countries favored border closures as a reaction to the pandemic (Ipsos Reference Jańczak2020). Against this backdrop, we argue that imaginaries of the borderlanders are more diverse and ambivalent due to their transnational experience than those of residents of inlands.

The section below analyzes the different discursive strategies as well as the various imaginaries which they used. The overwhelming number of comments on social media and in press articles argued against the border closures and their related restrictions, which was not unexpected considering the slogans appealing for opening the borders, returning to “old lives,” and “letting the people come back home.” Importantly, similar anti-rebordering discourse appeared in both twin towns, likely demonstrating a similarity in the challenges faced by border town residents. Noticeably, the protests were dominated by Polish interests appeals to the Polish government, which, according to the protesters, did not understand the uniqueness of living in the borderland. Moreover, due to the economic asymmetries across both borders, more Polish cross-border workers were affected, because they often found better employment opportunities in the Czech Republic and Germany. According to the estimated data, around 12,000 Poles 1 work on the Czech side of the borderland region, and 150,000 Poles on the German side (Hreczuk 2020).

The Bottom-up Perspective: Closing the Border as a Tragedy for Twin Town Residents

By employing the pragmatic line of argumentation, the border closure was seen as an unexpected and sudden obstacle that shattered normal life and made existing transnational everyday practices impossible. In recent years, the border had been “just a conventional line on the map” (Borderland Inhabitants’ Manifesto, 22.04.2020), something that was not experienced as a barrier, and which people used to cross on a daily basis. The closed border generated a wave of economic and personal tragedies as people—depending on which side of the border they stayed on—could not work or see their families. The posts discussing the situation of cross-border workers (often presented as victims of government policy) generated the most interest and emotional involvement. There were discussions about individual circumstances, involving unemployment, a worsening financial situation, and potential psychological problems (cf. Kasperek and Olszewski Reference Kenwick and Simmons2020). In addition to the plight of cross-border workers, protesters referred to the situation of (a) businessmen in a similar situation as their clients were usually residents of the neighboring country, and (b) cross-border students who could not continue their education. What is more, there were also everyday border-related challenges, such as a lack of continued medical treatment or transfer of goods (including medications) to relatives:

Can you imagine that the city is suddenly divided into two or even three closed parts? Surrounded by police, without the possibility to cross the new boundaries? Suddenly separated from each other, without the possibility to prepare yourself for that? You cannot go to work, you cannot come back home, you have no access to a doctor, you cannot visit your lonely disabled grandmother that you take care of who is on the other side of the city on her own. You cannot give her medication because the police do not let you do it. It is not science fiction, it is today’s reality for borderland inhabitants. The Polish government’s decision makes our work impossible and our coming home impossible! (Protest letter, 24 April, 2020).

People say in their names (such as workers and their families, people whose life is highly influenced by the revival of the border, protest supporters) and in the name of community: cross-border workers as well as “borderland inhabitants.” The local identity of borderland inhabitants was enhanced by the feeling of being ignored by central—governmental—authorities (especially the Polish government). By emphasizing the particularity of the borderland and its residents’ cross-border life, they (re)produce an imaginary of the transnational borderscape and cross-border region’s uniqueness. In official statements, they stress an understanding for the special circumstances surrounding the pandemic, while simultaneously assuring authorities that it is possible to keep to all safety standards with (at least partially) open borders. The Polish government’s decisions were presented as very broad, careless, and unfair. Some Facebook users expressed more radical, anti-governmental sentiments, pointing to the absurdity of specific regulations and, more generally, the manipulative political style of the Law and Justice, a governing party in Poland.

Both the media and local politicians for the most part shared the concerns expressed by protesting inhabitants and appealed to the Polish government to consider the unique conditions in the borderland and the potential economic and social consequences of closing borders. Although they expressed their understanding for safety regulations, they highlighted the same problems as the protesters had: there should be an option to cross the border for reasons of education, work, and health. Czesław Fiedorowicz, chairman of the Board of the Federation of Euroregions of the Republic of Poland, appealed to Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki to remove border restrictions within the Euroregions:

We live in a strong symbiosis and need each other. Guben for Gubin, Löcknitz for Szczecin, Zgorzelec and Görlitz, Cieszyn and Český Těšín, Nowy Targ and Kežmarok, Suwałki and Mariampol are supposedly “abroad,” but relationships between people, their place of work, residence, family ties, school and university, treatment, health care and daily contacts are often very deep (Wyborcza.pl/Zielona Góra, 19.04.2020).

Of interest, in case of the Polish-Czech twin town, local media differed in their involvement: While Czech media only reported on the situation (often quoting the same individual stories), Polish media took on the perspective of Polish cross-border workers and expressed openly anti-governmental positions. In the Polish-German case, local media in both countries supported the protesters and reported on the personal tragedies of cross-border commuters, families and students. Nevertheless, the most numerous and emotional comments appeared on the Słubice Facebook site “Nasze Słubice.pl,” revealing the asymmetric relationship between Słubice and Frankfurt/Oder with the Polish town as the economically weaker partner. Commentators also highlighted the wider borderland profits generated by cross-border traffic, including the revenues of hairdressers, entrepreneurs and traders. Against this backdrop, the border was perceived as a resource, and argumentation strategies reflect an imaginary of open borders as normalcy, as can be seen in a comment by a Polish social media user:

It is worth noting that we do not want to cross the border for recreational purposes! We are cured in Germany, our children go to German schools, our employer expects our presence at work! We don’t want to cross the border out of boredom, only for life’s necessities like the above! (FB_Nasze Słubice_39_20.04.2020).

According to certain inhabitants and local elites, the dramatic individual circumstances would be followed by a destabilization of the region as a whole. Considering that economic crises often envelop many countries simultaneously, such a line of argumentation demonstrates how locally based the narrative was. It also reproduced an imaginary of the borderland as a unique space marked by cross-border practices and relationships. Furthermore, some commentators argued that the border closures revealed two features of the borderland. First, Michael Kurzwelly, the founder of the Słubfurt (established in 1999 as an imagined town located half in Poland and half in Germany that should contribute through various cross-border projects to the integration of border communities in Frankfurt/Oder and Słubice), argues: “closing the border has clearly shown how interlinked we are, how much we share a common space. Hence, the good thing about this situation is that the authorities notice that it can’t be separated so easily. At least I hope so” (Gazeta Wyborcza. Zielona Góra, 24.04.2020). Second, others argued that the border closures demonstrated a weakness in the joint structures and a lack of agency as a twin town, leading to a “paper twin town”:

In my opinion, the rulers of the twin town did not bear the problems of the pandemic, which resulted from the weakness of common structures and the lack of action plans both in normal times and even more so in case of emergency. I think that as a twin town we should have our own subjectivity, we should be taken into account in all decisions of both states as one society, as one agglomeration (FB_Nasze Słubice_59_3.04.2020).

Summing up, this discursive stance demonstrated that commenting borderlanders, as well as local politicians and cultural elites, perceive the twin town even in the crisis as one inter-related system and open borders as self-evident what contrasts with nation-state imaginary of borders as security tools. However, the closure of the border made them aware how much of their lives was lived across national boundaries, but they were also forced to recognize that—in exceptional situations—the nation-states authorities still regarded them as separate bodies. As border management is in the national purview, the imaginary of Europe without borders is not as easy to achieve and maintain as they had believed (Wassenberg Reference Watkins2020, 37).

Normative Argumentation: Closing the Border as a Threat to an Integrated Europe

Apart from the above presented discursive stance that employed the small imaginary of everyday cross-border life, local politicians and cultural elites referred also to master narrative of an integrated Europe without borders. They framed the closure of the border as a potential risk to longstanding cross-border cooperation and perceived the demand for opening borders as a return to normalcy. Here, the closed border was constructed as a kind of “scalpel cutting through the organism”, dividing it into two halves. The metaphorical representation of the twin town as an organism expressed a dramatic situation connected to the question of rebordering. Based on the imaginary of the twin town as united—transnational, cross-border– borderscape, closed borders brought about a symbolic revival of history. A cultural activist from Cieszyn, Zbigniew Machej, commented that a closure of a Polish-Czech border was:

unnatural, a brutal separation which should not last a day longer than it is necessary. The majority of the people on the borderland instinctively feel that borders are bad, that borders are scars caused by huge trauma and disasters, by wars and totalitarianism. Thirty years of freedom, democracy, and European integration has created a new social, civilizational and cultural quality here […] (Forum Dialogu, 4.05.2020).

As elites are more often personally involved in cross-border cooperation and actions in favor of European integration, they also tend to refer more often to both the imaginary of the transnational town and a Europe without borders. In recalling the difficult history of Europe divided by the Iron Curtain, they emphasize cross-border reconciliation and friendship as an historical achievement and regard open borders as normal and not something be endangered by poor political decisions. Interestingly, even temporary rebordering seems to be a threat and the first step toward the break-up of the European Union. This interpretation simultaneously reveals the fragility of the imaginary of a Europe without borders in the region and the strength of historical remembrance. Moreover, elites described the situation as an unwanted change that influenced not only work and family, but also practices of recreation and leisure. In both twin towns, banners were hung that expressed longing for a neighbor and solidarity, as well as emphasizing European unity. Stefan Mańka, who co-authored banners on the Polish side of the river, and who co-directs the Polish-Czech NGO, states:

40 years ago, it was politics; today, it is a health care. Nobody could imagine such a situation a few days ago, and now it is reality. We already know how much-closed border influences our lives […] Cross-border communication, shopping, or cultural events—that is what we got used to in the last 30 years, and suddenly not everything is natural and obvious for Czechs, Poles, Germans or Slovaks (Człowiek na granicy, 6.04.2020).

While in the case of Polish-Czech borderland, the stress is more often on a common heritage and unified regional identity in Cieszyn Silesia; in the discourse on the Polish-German city, the imaginary of European integration is more present. Particularly in the discourse on the German Facebook site “Doppelt schön” references to the European idea were used more often than any pragmatic arguments. During the protests, people on both sides of the border sang the European anthem. On the occasion of Europe Day on 9 May, the imaginary of an integrated Europe without borders has dominated the discourse, as illustrated by one social media post:

The European vision of peace, cohesion and cooperation can inspire us every day to celebrate Europe - especially here on our beautiful Oder, right now! (FB_Doppelt schön_111_9.05.2020).

Some inhabitants also referred to the Schengen Area as an institutional guarantee of the right to cross the border, and underlined their European identity and open borders as one of the European fundamentals embedded in their lives:

Europe guaranteed all of that [cross-border opportunities] because in addition to the fact that we are Poles and we are going to remain so—we also feel ourselves to be free Europeans (Borderland Inhabitants Manifesto, 22.04.2020).

However, references to an imaginary of integrated Europe and a Europe without borders seem to have a greater strategic function in the quoted manifesto—enhancing the more practical line of argumentation. It is worth considering that these arguments are local- and EU-centered. To justify their stance, different actors refer to spatial imaginaries concerning their specific twin town, borderland region, and the European Union to regain the “normal” state of open borders and return to their previous practices, embedded in a given cross-border borderscape.

Health and Safety as Primary Values

In the analysis of the discourse surrounding border closures in both twin towns, some pro-rebordering comments were also registered during the period in question. It must be noted that they appeared in individual comments rather than in the discourse presented by protesters, the media, and local elites.

This third discursive strand, based on a pragmatic line of argumentation, was constructed with reference to arguments about health and safety that were also used by the Polish and other European governments to legitimize border closures as a means of limiting the spread of the pandemic. Within this argumentation, nation states, with their closed borders, are perceived as gatekeepers who deploy their available competencies to protect their populations. The imaginary of a common, transnational borderscape does not constitute here a point of reference. In line with state discourse the border is constructed as a barrier against external threat (the virus) and a guarantee of national safety, paralleling a more widespread “linguistic rebordering,” which constructed the disease as foreign-rooted by assigning its existence and spread to other nations (Nossem Reference Ohmae, Lechner and Boli2020). Border controls then “satisfy the need for the State to appear to provide security” (Kenwick and Simmons Reference Klatt2020, E45). Within this argumentation line cross-border workers were seen as potential hosts of the virus, building on a common assumption that staying within state borders is safer than crossing them, despite the short distances. A variety of strategies among the EU countries served as an argument against open borders (cf. Nossem Reference Ohmae, Lechner and Boli2020). As Czech Facebook users argued, border closures were especially important as different countries used different strategies to counter the pandemic. According to them, the Polish government (contrary to Czech politicians) did not do enough testing, making it hard to estimate the real scope of the pandemic in Poland and thus it is safer to keep the borders closed as long as possible. As the research showed (STEM, 30.03.2020 2 *), Czech people generally assessed rebordering for health and safety reasons positively, which is reflected in some of the comments collected:

I also do not like that I cannot go to Cieszyn. However, what can we do when this arch-enemy (corona) has still not been defeated. What we can do is to wait it out. It will be better again (FB_Město Český Těšín_29_25.04.2020).

Additionally, approval for the decision to close the borders can be linked to a more general Euroscepticism in Czech society:

Because of the unusual situation, it is right that both parts of the city are divided and the border exists and protects. We understand that some citizens have problems because of that, but it is not forever. It is better to be alive than dead and sick. The EU is very unpopular among the majority of Czechs nowadays, so walking with EU flags is not very welcome as the EU did not help […] (FB_comment_Open Borders event PL/CZ_23_9.05.2020).

For some commentators, references to the imaginary of European integration and the EU were less valued than more pragmatic argumentation. Some Polish commentators from the Polish-Czech border region also supported closed borders and referred to national solidarity and rational necessity, stating that people working in Poland had the same problems with jobs and meeting relatives due to the regulations. Notably, they locate their points of reference not in the peculiarities of the borderland region, but in the nation-state, insofar as not only crossing the borders but also protesting publicly were understood as thoughtless actions and a potential space for pandemic spread.

Similar arguments were also used by commentators from the Polish-German border town, although it must be stressed that this perspective was observable only among Polish users commenting on the Nasze Słubice.pl Facebook page. There was a clear aversion to cross-border workers, justified by the need to maintain security measures.

The borders should be sealed even tighter and not opened. Including truck drivers, who should be under more control than they are now (FB_Nasze Słubice_36_17.04.2020).

Cross-border workers were accused of selfishness, a desire for profit. They were portrayed as individuals who did not care about their relatives and put the Polish society as a whole at risk. The often very emotional comments paint a picture of “the others” or “strangers” from abroad who pose a danger and could bring the plague. Importantly, being a Pole and living in Poland but working across the border can complicate the obviousness of inclusion into (national) “us.”

National Interests in Focus

The fourth identified line of argumentation expressed nationalist tensions at the local level. Closed borders were constructed discursively as a guarantee of order and security in the town limited to the national territory. From such a perspective, the imaginary of a transnational borderscape could be seen as an illusion, divorced from reality. In the Polish-German twin town, some Polish social media commentators emphasized that Słubice and Frankfurt/Oder were two separated cities governed by two sovereign nation-states which pursued individual policies and took the steps they considered appropriate, thus contesting the idea of twin town.

Notably (especially in the Polish-German case), the revival of borders awakened old historical tensions and stereotypes. Within this discursive strand, a few references to the Second World War and the image of Germans as an aggressor that established concentration camps, called themselves the Herrenvolk and still posed a threat to Poland in their national unpredictability. Here, the cross-border relationship was constructed by referring to national and not local identities. To some extent, this phenomenon was also visible in the Polish-Czech case, where protests with Polish flags on both sides of the border were presented as a negative flashback to previous Polish-Czech conflicts and the 1938 annexation of Cieszyn Silesia by the Poles. As artist, sociologist, and member of the city council in Cieszyn, Joanna Wowrzeczka observed, for the most part, Czechs did not join the anti-rebordering protests. According to her, it turned out that they “are not always happy while listening to the Polish language next to them.” Certain Czech Facebook users confirmed that line of thought, commenting that Poles, especially homeless individuals, spend a lot of time on the Czech side of the river and cause untidiness there. Interestingly, Polish commentators rarely commented negatively on the Czechs, although, in the reaction to negative attitudes stemming from the Czechs, a certain rivalry became apparent in terms of which city needed its cross-border neighbor more:

The whole of Český Těšín used to shop ONLY in Poland…That is because you cannot buy anything you need in Český Těšín except for products in the supermarkets and Vietnamese shops (FB_Město Český Těšín_29_25.04.2020).

The anti-migrant sentiment among some Czech commentators was, however, based on economic considerations: there were fears that Poles take jobs away from Czechs—a situation possibly exacerbated by a potential economic crisis. Such also threats appeared in the interviews with Joanna Wowrzeczka, who stated that transnational relations and integration there requires much further work:

Maybe Czechs want to keep their labour market inaccessible for foreigners in case of harsh austerity and predicted unemployment; but—who knows—maybe a love on both sides of the river is still an object of desire and fantasy rather than a reality. And although it works well on the cultural level, it is still platonic on the political and structural level (Krytyka Polityczna, 25.05.2020).

Importantly, the criticism of people working abroad was expressed by FB commentators of all nationalities. Discussions about better working conditions in Germany or the Czech Republic involve stereotypical statements about colonized Polish-German relations, “cunning” Poles, or “exploitative” Germans. Even positive attitudes expressed by Frankfurt/Oder residents of solidarity and longing for a neighbor during the protests were interpreted by some Polish discussants as a desire for cheap labor and products:

You can’t say that a German misses a Pole, but a German misses the bazaar, cigarettes, and fuel. (FB_Nasze Słubice_59_3.04.2020).

From this perspective, the negative image of Germans as national community and not local neighbors being demanding and rude when in Słubice was validated:

It’s true…they come into the restaurant speaking in German…there are also some, who, if you answer them in Polish, they’ll make a face, as if I don’t know what…because a Pole speaks to him in Polish… And if you don’t understand them at all… they’ve got a lot of nerve… it’s everyday life at work. […] (FB_Nasze Słubice_40_20.04.2020).

Moreover, the image of Polish cross-border workers was constructed to highlight their disloyalty to Poland, by pretending to be German and criticizing Polish people; yet, they should nonetheless stay in Germany and live there. It must be underlined here that, although this line of argumentation was not widespread among Polish Facebook users, it nevertheless demonstrates that old historical traumas are still alive in the collective memory, able to re-emerge in times of crisis.

Within this discursive strand the imaginaries of the nation-state and closed borders as a guarantor of safety and respect for the national rights and interests were predominant. Thus, the imaginary of a united transnational city was questioned, revealing tensions surrounding everyday experiences, economic asymmetries, and historical conflicts.

Discussion and Conclusions

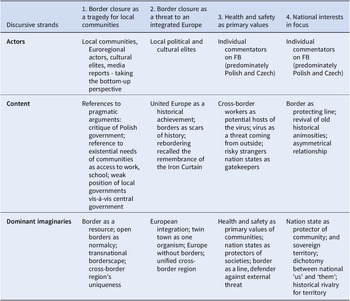

The sudden border closure has revealed a fragility of local imaginary of transnational borderscape and the weakness of local actors vis-à-vis governmental authorities. As Table 1 demonstrates within the discourse on border closure, we could identify four discursive strands that show both opponents and supporters of rebordering politics.

Table 1. Four discursive strands on border closure.

Source: Authors.

The critique of border closure was dominant throughout the entire debate and was represented by both local communities and elites. Their argumentation also influenced the way in which local media and politicians covered the issue. In their anti-rebordering perspective, actors referred to the imaginaries of the cross-border region’s uniqueness and a Europe without borders (including long-standing practices and Schengen regulations) as normalcy. Border communities used the arguments of their existential needs that could be met only by cross-border practices. Hence, border reinforcement was discursively constructed as a personal tragedy. The anti-rebordering discursive strand was also constructed by local cultural and political elites. However, they used rather the normative line of argumentation and the imaginary of an integrated Europe. Yet, the border closure was discussed within a local and European framework, regarding the imaginaries of twin towns, a unique borderland region, and a Europe without borders (limited to the EU).

Nevertheless, within the analyzed discourse we identified also two, more national-oriented, strands that supported the border closure. They were represented by ordinary inhabitants commenting the situation on Facebook pages. It should be mentioned that similarly to the anti-rebordering perspectives, they also used pragmatic and normative argumentation strategies. The former referred, in accordance to state argumentation strategy, to health and safety as primary values of societies reproducing the imaginary of a secure, bounded nation state, and the border as a protective barrier against the virus carrying by “the others.” The latter revealed, more openly nationalist and stereotype-based attitudes, including the revival of (regional and national) historical conflicts, as well as anti-migrant sentiments based on economic asymmetries. This pro-rebordering discursive strand did not resonate as much in the analyzed media and in public discourse. Importantly, the arguments here were constructed with reference to spatial imaginary limited by (safe) materialized national boundaries, without perceiving the space “beyond the line” (Brambilla Reference Brambilla2015, 17) as a part of their “own” world.

The distinguished discursive strands do not create black and white pictures. Although they encompass argumentations for or against border closure it is necessary to remember that the analysis grasped the first stage of rebordering and people’s reactions were dictated by their personal situations, interests as well as emotions. Normative argumentation strategy referring to the project of integrated Europe seems to be more internalized by local elites than borderland communities. They, in contrast, tend to use a more pragmatic orientation that is more contextualized and situational. What is more, it is the nation state and not the European Union that is perceived as a guarantor for security and order.

Nevertheless, taking into consideration the scale of border-based challenges, one can assume that the experience of closing borders has created more favorable conditions for further reproduction of imaginary of border as a problem rather than a protector. According to our findings, it can be argued that border closure manifested and made border residents more aware of how connected the twin towns were and are and, in line with our theoretical assumptions, it functions more as transnational, multifaced, and multilevel borderscape than a territorial separating line. What is more, it showed economic interdependences within regional cross-border imaginaries: restrictions in border permeability made transnational flows more complicated and hence, influenced both the individuals’ lives and regional economic situation. It is worth noting that the critique on rebordering by using the pragmatic perspective came predominately from Polish commentators and, thus, revealed the economic asymmetries along the two borders. These asymmetries were more noticeable in the Polish-German case, especially as more Poles work in Germany, leading also to a greater interdependency: some German companies, as well as health and social care institutions, rely heavily on Polish workers.

Moreover, the Polish-German cross-border cooperation in Słubice and Frankfurt/Oder, as well as political efforts toward integration and the construction of the image of a single transnational city (e.g., by using one city brand; Opiłowska Reference Opiłowska2017) testify to an advanced level of transnational integration. Cooperation in the Polish-Czech case is also an important factor, but it is most noticeable in cultural and infrastructural areas, most often funded by the EU. In addition, the imaginary of one Polish-Czech city is not as embedded in local politics and public discourse as in Polish-German case. It may result from the less developed institutionalization of cross-border cooperation or from the more regional-based legacy of conflict in Cieszyn Silesia.

As argued in the theoretical section, crisis can create advantageous conditions for (re)emerging imaginaries (Sum and Jessop Reference Taylor2013). Nevertheless, our analysis has demonstrated that different borderland actors tend to refer rather to “old” catalogue of available spatial imaginaries of the cross-border town, integrated Europe without borders, or a safe nation-state rather than create new ones. Taking into consideration that many borderlanders function within transnational borderscapes, the sudden rebordering has provoked debordering arguments approving the recent (defined as “normalcy”) status quo in everyday discourses. Hence, our study has shown how bigger imaginaries can be made useful in argumentation strategies of local actors.

Although our analysis reveals discourse on the border closures in only two selected twin towns in a specific moment of pandemic, other studies (Wille and Kanesu Reference Wille, Weber, Mein and Pause2020) suggest that similar reactions could be observed in a wide range of European border regions. Furthermore, it was an attempt to capture a dynamic situation, wherein any changes in border management are felt soonest by people in borderland regions. The context of borderlands as a space where at least two nations and different levels of governing (European, national, regional, local) meet and overlap demonstrates the importance for further research to focus on the consequences of the present situation on future cross-border cooperation, including its structure, opportunities, (new) strategies (Wille and Weber Reference Wille, Weber, Mein and Pause2020), as well as imaginaries and identities. Moreover, taking into consideration that crises and growing uncertainties create favorable ground for exclusionary nationalism, the further research should also focus on the impact of pandemic on border politics of nation-states as “it appears that the current pandemic has hastened movement away from international cooperation and reinvigorated a my-nation-first approach” (cf. Kenwick and Simmons Reference Klatt2020, E 55).

Financial support

This article is part of the research project “(De/Re)Constructing borders—narratives and imaginaries on divided towns in Central Europe in comparative perspective,” financed by the National Science Center within the OPUS framework, UMO-2018/29/B/HS6/00258.

Disclosures

None.