Forms of National and European Identity in Europe

With Euroskepticism on the rise (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Isernia et al. Reference Isernia, Fiket, Serricchio, Westle, Sanders, Magalhaes and Tóka2012; Gernand Reference Gernand, Bach and Hönig2018) and right-wing populist parties fuelling discourses about the ‘true’ national and European people (Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2016), the European Union (EU) is facing numerous challenges. The question of “Who belongs to the nation or Europe?” is becoming more salient as immigration rates increase, evoking social comparisons of foreigners and conationals (Theiss-Morse Reference Theiss-Morse2009). At the core of those questions is a certain “we-feeling” that generates the awareness of belonging together as a group, sharing common political structures and fate (Easton Reference Easton1965). Without such a common identity, an essential characteristic of legitimate democratic rule with the prospect of stability (e.g., Westle Reference Westle2003a) and a core requirement for social cohesion is missing (Arant et al. Reference Arant, Dragolov and Boehnke2017). A common identity can act as glue that holds the citizens together by reducing social conflict, while increasing the willingness to cooperate, which in turn enhances the production of public goods, facilitates the democratic consensus-building processes, and allows for more efficient collective action (Tamir Reference Tamir1993; Canovan Reference Canovan1996; Miller and Ali Reference Miller and Ali2014).

Investigations about National and European identity on the micro level have drawn some attention in the past. Previous articles have focused on questions regarding the intensity or different relationships between national and European identification (Westle, Reference Westle2003a) as well as on their determinants or consequences (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2004; Clark and Rohrschneider Reference Clark and Rohrschneider2019). One of the main findings remains that national identification is stronger than identification with Europe and that European identification does not seem to change significantly over time (Duchesne and Frognier Reference Duchesne, Frognier, Niedermayer and Sinnot1995; Westle and Graf Buchheim Reference Westle, Buchheim, Westle and Segatti2016). Regarding aggregated attachment to Europe over time, from 1970 to 2007 there is no indicator for attachment to Europe moving up (Isernia et al. Reference Isernia, Fiket, Serricchio, Westle, Sanders, Magalhaes and Tóka2012) and even from 2008 to 2013, after the financial crisis, there are only marginal changes in attachment to the EU (Bergbauer Reference Bergbauer2017). Overall, attachment to Europe seems to neither increase nor decrease significantly over time.

But why is Euroskepticism on the rise when the strength of European identity has not changed? One possible explanation could be that the meaning citizens attach to national and European identity are not taken into consideration in studies that measure national and European identity as a one-dimensional construct, such as attachment (Dennison et al. Reference Dennison, Davidov and Seddig2020), feeling of belonging (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2004; Koos Reference Koos2012), or closeness to the nation/the EU (Plescia, Daoust, and Blais Reference Plescia, Daoust and Blais2021). Only few contributions consider what it means for citizens to identify with their nation or with Europe. Although there are some qualitative approaches to measuring the meanings or contents of national or European identity for some countries (Bruter Reference Bruter, by, Risse and Brewer2004a, Reference Bruter2004b), those approaches do not allow for large-scale cross-country comparisons. This article therefore asks which forms of national and European identity were found by previous research on the basis of standardized cross-national survey data. What are the similarities and what are the differences regarding their meaning and their contents? Which determinants and consequences accompany these different forms on the micro level? To answer these questions, the objective of the present literature review is to analyze quantitative articles that concern different meanings, objects, or contents of national and European identity, summarized under the term “forms” of national/European identity.

The following part will give an overview of theoretical approaches to forms of national or European identity. Thereafter, the basis on which the articles have been researched and selected is presented and the different operationalizations of forms across international surveys are reviewed. Then findings about which specific forms were found are compared, and a brief overview about determinants and consequences of these forms is presented. This article closes with the conclusion and discussion.

Theoretical Approaches on Forms of National and European Identity

In social psychology, social identity theory (SIT) is the most recognizable approach when it comes to explaining group identities. Social identity is described as “that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1974, 69). This collective social identity contains cognitive, affective, and evaluative elements (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1982). Further described in the self-categorization theory (SCT; Turner et al. Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987), individuals cognitively refer to social categories as prototypes, capturing intragroup similarities (assimilation) and intergroup differences (contrast). These “symbolic boundaries” separate a collective and internal “us” from a diffuse “them” (Eisenstadt and Giesen Reference Eisenstadt and Giesen1995; Hogg and Reid Reference Hogg and Reid2006). By shaping what it means to be part of a specific group, the content of an identity is constructed. This is what the term form is supposed to capture in this review. If an individual self-categorizes to belong to a certain social group, the groups’ identity is adopted through social identification and individuals’ self-esteem will become bound up to this social group (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979).

Constructivist approaches regard identity as a product of social cognition within social groups that is open to processes of change (David and Bar-Tal Reference David and Bar-Tal2009). A group identity emerges when a number of individuals identify with the same object while being aware of this identification (Lichtenstein Reference Lichtenstein2014). Although some argue this awareness of belonging together is mainly enforced by elites (Giesen Reference Giesen1993), it can also be based on individual feelings of togetherness. One source of identification can be based on the assumption of communalities between group members that contrast differences to outsiders (Estel Reference Estel, Hettlage, Deger and Wagner1997). In the national and European context, such similarities can only be assumed, as most of the group members cannot be experienced personally. Such social groups are often referred to as “imagined communities” (Anderson Reference Anderson1991, 49).

Both approaches share the prerequisite that an individual has to refer to the specific social group as part of its self-understanding. On the individual level, the relationship between a person and a group can be considered as vertical identification, describing an individual’s specific perceptions of sharing precious and exclusive commonalities characterizing the group (belonging to). On the group level, collective identity is based on horizontal relationships between group members who share a common collective identity (belonging together; Eisenstadt and Giesen Reference Eisenstadt and Giesen1995; Westle Reference Westle, Brettschneider, van Deth and Roller2003b; Kaina Reference Kaina2012). This sense of belonging together can also be a part of an individuals’ psychology; therefore, vertical as well as horizontal identification can be applied to the micro level.

Potential Forms of National and European Identity

Research on forms of national identity is a lot more extensive than on European identity. Thus, it was decided to structure this part along relevant theories of forms of national identity, whereas theories about forms of European identity are mentioned separately at the end of this part.

In political science, macro-level theories of nation-building offer directives for the investigation of forms on a more micro level. The most prominent approach stems from Kohn’s work on nationalism (Kohn Reference Kohn1944), which is in turn rooted in previous insights of Meinecke’s distinction between Staatsnation (state nation) and Kulturnation (culture nation) of nation-building processes (Meinecke Reference Meinecke1908, Reference Meinecke and Kimer1970). A civic nation is founded upon political institutions and political ideals, whereas an ethnic nation is built upon the belief in a historical, prepolitical culture uniting the nation. Although the ethnic form is assumed to be more prominent in Eastern European countries, Western European countries are mostly based on civic conceptions (Kohn Reference Kohn1944). One point of interest is therefore to see whether these theoretical discrepancies between Eastern and Western European countries are found empirically.

A similar approach differentiates between the demos and ethnos principles as nation-founding ideas. Following the principle of the ethnos, a nation is built upon common ancestry, history, place of birth, socialization, and culture, whereas the idea of demos does not attribute any relevance to ethnic or cultural factors but instead relies on the commitment to democracy (Francis Reference Francis1965). This distinction can be transferred to the micro level and is referred to as “ethnic–civic dichotomy” (Giesen and Junge Reference Giesen, Junge and Giesen1991; Ignatieff Reference Ignatieff1994) or ascribed and achieved social identities (Huddy Reference Huddy2001).

The ethnic form is often linked to organic/illiberal/exclusionary and the civic to rational/liberal/inclusive tendencies of the nation (Brown Reference Brown1999). While some argue that societies are either ethnic or civic (Miller Reference Miller2000), others criticize those different forms of national identity are considered simultaneously (Smith Reference Smith1991; Giesen Reference Giesen1993; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004). Even though the ethnic–civic dichotomy is the most common typology that is used to distinguish different forms of national identity, there are also alternative approaches and the critique that a simple dichotomy is not able to cover the complexity of national identity (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka and Beiner1999; Nielsen Reference Nielsen and Beiner1999; Kuzio Reference Kuzio2002).

Some researchers argue that ethnic and cultural aspects should be distinguished from each other because ancestry or the place of birth is inherent and therefore clearly more restrictive toward outsiders than cultural aspects (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka and Beiner1999; Nielsen Reference Nielsen and Beiner1999). In line with this argument, Eisenstadt and Giesen (Reference Eisenstadt and Giesen1995) developed a theoretical model of collective identity that contains primordial, civic, and cultural forms.

On the other side, it might occur that cultural aspects interweave with the ethnic or civic form. Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2004) states that it is not possible to say whether an element is clearly civic or ethnic, and cultural aspects belong to both. Ethnic nationalism is always ethnocultural and civic nationalism, as a purely acultural understanding of nationhood, is not widely held. This means that besides being a stand-alone cultural form of national identity, cultural aspects might merge with the previously formulated civic and ethnic forms. A common language and culture can be seen as part of the political aspects of a nation, as common language is essential for participation and cultural aspects such as norms are essential for common laws and the political rules of living together. Cultural heritage such as a common history and religion can be seen as parts of ethnicity and might belong to an ethnic or ethnocultural form. Empirically, this will be reflected within the problems of assignment of single items to specific forms of national identity.

Another source of identification might derive from the economic, social, and welfare systems of the nation. Economic outputs and welfare benefits, as well as technological and scientific achievements, may be seen as sources for a socioeconomic form of national identity. Previous studies on national pride hint at the high relevance of economic aspects, although doubting the stability of economic issues and thus whether they can constitute a form of collective identity (Mohler and Götze Reference Mohler, Götze, Mohler and Bandilla1992). Socioeconomic aspects, similar to cultural, might interweave with the civic or ethnic form of national identity, as questions about the distribution of socioeconomic goods depend on the underlying concept of who is regarded as eligible.

Another field in political science that might contribute to specific forms of national and European identity is the field of nationalism and patriotism. Variants of nationalism or patriotism might be closely linked to conceptions of national identity. Nationalists often idealize their nation and decide who belongs to it based on descent, race, or heritage (Kosterman and Feshbach Reference Kosterman and Feshbach1989; Blank and Schmidt Reference Blank and Schmidt2003; Huddy Reference Huddy, Grimm, Huddy, Schmidt and Seethaler2016). This highlights some similarities to ethnic national identity. Constructive patriots cherish humanistic and democratic principles and endorse citizenship toward the state, if they see those ideals endangered (Schatz, Staub, and Lavine Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999). This clearly shares some similarities with the concept of civic national identity. Nevertheless, from a sociopsychological point of view, nationalism and patriotism do not refer to the content of identity directly. Past research often confounded the content of identities with processes of identification. The latter addresses the cognitive or affective orientation toward a group, such as nationalism or patriotism (Ditlmann and Kopf-Beck Reference Ditlmann and Kopf-Beck2019). Also described as modes of identification (Roccas and Elster Reference Roccas, Elster and Tropp2012), items for these concepts often ask how strongly respondents identify with different identity content. Some researchers even highlight the distinctiveness to forms of national identity by declaring nationalism and patriotism as consequences of them (Blank and Schmidt Reference Blank and Schmidt2003). As this literature review focuses on contents or forms of identity, it was decided to not include studies that investigate variants of nationalism or patriotism.

Although, some researchers argue that national pride can be equated with patriotism (Rose Reference Rose1985) or even nationalism (Solt Reference Solt2011), it is still regarded as an important and distinguished component of social identity (Smith Reference Smith2007). In line with a differentiation between an abstract general national pride and pride toward specific domains (Evans and Kelley Reference Evans and Kelley2002), Hjerm (Reference Hjerm2003) suggests a differentiation between political (civic, economic, and social security) and cultural (history, cultural practices and achievements connected to the people) national pride. In sum, scholars of nation-building, nationalism, and patriotism, as well as national pride, point to the existence of at least an ethnic/cultural and a civic form of national identity.

Europe can be regarded as a culturally and historically defined social space, and the EU as a distinct civic and political entity. Previous qualitative studies indicate that this distinction is valid in the minds of the citizens in Europe (Bruter Reference Bruter, by, Risse and Brewer2004a, Reference Bruter2004b). In contrast to national identity, this allows for a clearer distinction of cultural and civic identity. Similarly, a distinction between the EU as a common cultural heritage and a political project can be drawn (La Barbera, Ferrara, and Boza Reference La Barbera, Ferrara and Boza2014). The cultural form of European identity derives from a common historical-cultural memory and heritage of Europe (Eder Reference Eder2004) and is the outcome of cultural conditions within European civilization (Delanty Reference Delanty2005).

The civic form describes the relationship between people and the EU in the same manner as on the national level, focusing primarily on the political institutions, citizenship, and the legal implications of it (Shaw Reference Shaw1997). When thinking about the EU’s original idea as an economic community, a potential socioeconomic form of identity might be especially important for the European level. In line with that, Lichtenstein (Reference Lichtenstein2014) distinguishes between an economic (single market, currency), political (democratic values), cultural (e.g., history, religious values), and geographic (borders) community.

Presented concepts of a cultural form of European identity contain aspects such as a common history and religious values and are thus ethnocultural. Besides those aspects, this article argues that European identity construction may also be based on more essentialistic traits, such as the place of birth or having European ancestry.

Selection Criteria, Data, Measurement, and Operationalization of the Articles

This literature review compares empirical contributions on the basis of standardized survey data about different forms of national and European identity on the micro level. To find relevant literature, a list of different search terms (Appendix I) was created and applied to different scientific search engines and databases.Footnote 1 Then, relevant articles were selected based on the following:

(a) Content Criteria

The studies must investigate different forms (meanings) of national or European identity. This excludes studies that operationalize identity with one-dimensional measures such as questions about attachment, closeness, or belonging to a nation or Europe. As mentioned in the theory part, studies about nationalism and patriotism are also excluded. It was decided to keep this as a strict limitation to improve the comparability between the studies and to limit the already large body of literature. Although, studies about nationalism often use similar measures, the articles must explicitly mention investigating questions of identity as their main focus of analysis.

(b) Formal Criteria:

The underlying data has to be based on cross-national surveys. As the objective of this literature review is to summarize studies about different forms of national and/or European identity in Europe, the articles must yield a comparative character. As a minimum requirement, articles have to analyze at least three European countries. Single-country studies were excluded. Also, the articles have to be published in English. The starting point of the analysis was determined to be the year 1995 when the first national identity module of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) was introduced, as this turned out to be the most used data source.

First, an overview about the data sources, measurements, and operationalization of all articles found will be presented. As the different operationalization of forms is the core concern in the field of national and European identity research, this part focuses on the different approaches found. To do so, articles are ordered according to the cross-national survey data they are based on.

International Social Survey Programme

The national identity module of International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) has been conducted in three waves in 1995, 2003, and 2013. Table 1 summarizes all studies based on these data and gives detailed information about the assignment of its items to specific forms (see Table 1). The publications are ordered according to their derived forms of national identity. As the survey only focuses on national identity, European forms cannot be considered.

Table 1. ISSP true national question

The first and dominant approach to measuring forms of national identity was introduced within this survey. Respondents were asked about the importance of different aspects of being a true member of the national group (which from here on will be referenced as the ‘true national’ battery). The intention of this question is to measure forms of national identity based on the societal boundaries of the respondents. An item for the importance of having national ancestry was added in the second wave. In the second and third wave, the question and its specific items are the same. It is difficult to tell whether the question measures horizontal or vertical identification, as the question can be understood in various ways.

Although not worded identically, most studies follow the logic of the ethnic-civic dichotomy. Two studies identify a cultural vs civic form distinction (Shulmann Reference Shulman2002; Koos Reference Koos2012).

Some researchers focused on the ethnic form only (Ariely Reference Ariely2019, Reference Ariely, Zajda and Majhanovich2021; Canan and Simon Reference Canan and Simon2019). Jayet (Reference Jayet2012) distinguished between respondents according to the importance they give to any of the criteria overall.

There are some similarities and differences in the assignment of items to forms. The item being born in the country was ascribed to the ethnic form in all studies, being supplemented by the ancestry item since it was added in 2003. Not as clearly assigned to the ethnic form was the item representing belonging to the dominant religion, which in some studies was part of the ethnic form (Heath, Jean, and Spreckelsen Reference Heath, Jean and Spreckelsen2009; Berg and Hjerm Reference Berg and Hjerm2010; Reeskens and Hooghe Reference Reeskens and Hooghe2010) while others regarded it as cultural indicator (Koning Reference Koning2011; Vlachová and Hamplová Reference Vlachová and Hamplová2023). Some also allocated the residence item (Hjerm Reference Hjerm1998; Jones and Smith Reference Jones and Smith2001) to the ethnic form and others to the civic form (e.g., Shulman Reference Shulman2002; Koning Reference Koning2011). Although giving importance to the place of birth seems to be the core feature of ethnic national identity, when thinking about it in terms of the jus soli versus jus sanguinis, it can be regarded as a feature that makes acquiring citizenship more accessible in comparison to ancestry.

Nearly all studies including a civic form assigned the respect for laws and institutions item to it. Although some regarded language also as part of the civic item (Hjerm Reference Hjerm1998; Berg and Hjerm Reference Berg and Hjerm2010; Aichholzer, Kritzinger, and Plescia Reference Aichholzer, Kritzinger and Plescia2021), others allocated it as a part of an ethnocultural form (Haller and Ressler Reference Haller and Ressler2006; Pehrson, Vignoles, and Brown Reference Pehrson, Vignoles and Brown2009). The different allocation of items to factors might be explained by measurement inequivalence, indicating that the meaning of specific items varies between countries (Heath, Jean, and Spreckelsen Reference Heath, Jean and Spreckelsen2009).

Jayet (Reference Jayet2012) distinguished respondents according to the importance they give all of the criteria overall, building no clear form. Ariely (Reference Ariely2020) used relativized scores (Wright, Citrin, and Wand Reference Wright, Citrin and Wand2012), and in his following work (Ariely Reference Ariely, Zajda and Majhanovich2021) he used a single-item measure (ancestry) for an ethnic form of national identity only. Taniguchi (Reference Taniguchi2021) used single-item measures for the ethnic (ancestry), civic (institutions and laws), and cultural (language) forms of national identity.

Larsen (Reference Larsen, Holtug and Uslaner2021) combined the true national battery with measures of intensity of national identity and distinguished between ethnic and civic national identity. The former consisted of people assigning religion and being born in the country importance, but respecting laws and institutions, speaking the language, and feeling national was viewed as unimportant. The latter contained those who gave high importance to respecting laws and institutions and low importance to being born or having residence in the country or sharing the dominant religion.

Beyond the usual variable-centered approaches that mostly produce an ethnic-civic factor solution, May (Reference May2023) chose latent class analysis as a person-centered approach. Four ideal-typical patterns of national boundary making were repeatedly found across 42 countries and all three waves of ISSP. May differentiates between (1) the “Exclusionists” (rating all criteria high, except for religion), (2) the “Assimilationists” (rating all criteria high, born and residence only moderately high, rejecting religion and ancestry), (3) the “Integrationists” (high support for language, laws, and institutions; rather supporting citizenship and feel; rejecting born, religion, and ancestry), and (4) the “Pluralists” (rejecting most criteria).

The ISSP also included questions about national pride. Two articles were found to connect those questions to national identity (see Table 2). Based on this question, Domm (Reference Domm2004) differentiates between political and cultural national pride. By merging the true national question with a question about national pride, Koos (Reference Koos2012) finds an ethnocultural, welfare, and great-power civic form of national identity The presented forms are additionally distinguished and labeled as “pragmatic” (e.g., ancestry, born, religion = ethnocultural; residence = ethnocultural/pragmatic). The welfare-civic form shows some similarities to a socioeconomic form of national identity (fair and equal treatment of all groups, social security system), whereas other socioeconomic factors are labeled as “pragmatic” (economic, scientific, and technological achievements).

Table 2. ISSP National Pride

European Values Study

Of the three studies based on data from the European Values Study (EVS) and World Values Survey (WVS) data (see Table 3), two of them focused on forms of national identity (Ariely Reference Ariely2013; Simonsen and Bonikowski Reference Simonsen and Bonikowski2019), one on national and European identity (Wegscheider and Nezi Reference Wegscheider, Nezi, Bayer, Schwarz and Stark2021), and one on European identity only (Voicu and Ramia Reference Voicu and Ramia2021). All of them used the imported true national battery of ISSP, which was also translated into an additional item for the European forms in EVS 2018. Articles based on these data revealed the ethnic–civic dichotomy.

Table 3. Studies based on EVS data

Simonsen and Bonikowski (Reference Simonsen and Bonikowski2019) differentiated between thin (rating all criteria low), thick (rating all criteria high), undifferentiated (all criteria neither high nor low), and constitutional (institutions and laws, language) forms. Ariely (Reference Ariely2013) decided to measure ethnic (ancestry) and civic (institutions and laws) forms via single indicators and further used relativized scores (Wright, Citrin, and Wand Reference Wright, Citrin and Wand2012), which indicates the surplus of importance of the ethnic form over the civic form, as most respondents rate civic criteria high, anyway. Wamsler (Reference Wamsler2023) differentiates between ethnic (born and ancestry) and civic national identity (laws and institutions and language). The only study focusing on forms of national and European identity simultaneously (Wegscheider and Nezi Reference Wegscheider, Nezi, Bayer, Schwarz and Stark2021) differentiated between ethnic and civic on both national and European level. Again, ancestry and born are assigned to the ethnic form of national and European identity. Voicu and Ramia (Reference Voicu and Ramia2021) tested for measurement inequivalence of the cultural and ethnic form of European identity. Their results point towards a common understanding of an ethnic form of European identity (born, ancestry, and religion) but an uncommon conception of a cultural form. This means that cross-country comparisons based on EVS 2017 data are possible for ethnic European identity, but not for the cultural form. On the European level, religion was also added to the ethnic form. The national civic form contains institutions and laws, language as well as culture. On the European level, the civic form contains culture. This contrasts with the theoretical expectation of a civic–culture dichotomy on the European level but also indicates that a more primordial ethnic form might exist on the European level. In contrast to the theoretical conceptions previously introduced, an ethnic form of European identity is formulated which contains ethnocultural (religion) and purely ethnic items alike (born and ancestry).

Integrated and United Project

The four articles based on data from the 2007 Integrated and United Project (IntUne; see Table 4) used the “true national/European” battery to measure respective forms and transferred the national questions to the European level. Compared with the original true national battery from ISSP, the items “exercising citizen rights” and “sharing cultural traditions” were added.

Table 4. Studies based on IntUne data

Best (Reference Best2009) finds an ascribed and acquirable form on the national level, with cross-loadings of the cultural tradition item. Serricchio and Bellucci (Reference Serricchio, Bellucci, Westle and Segatti2016) identify the same forms on the national and European level. Guglielmi and Vezzoni (Reference Guglielmi, Vezzoni, Westle and Segatti2016) discovered that parts of the meanings of national and European identity seem to merge and found a national and European civility form but a merged ancestry, citizenship, and Christianity form. This has been replicated in Segatti and Guglielmi (Reference Segatti, Guglielmi, Westle and Segatti2016). This indicates that national and European ancestry, citizenship, and religion refer to common forms of identity in the minds of Europeans, whereas in the case of civility, they still distinguish a national from a European one.

Across all studies, the “born” and “ancestry” items are assigned to the ethnic form on both the national and European level. Respecting institutions and laws as well as exercising citizens’ rights are constantly assigned to a civic form.

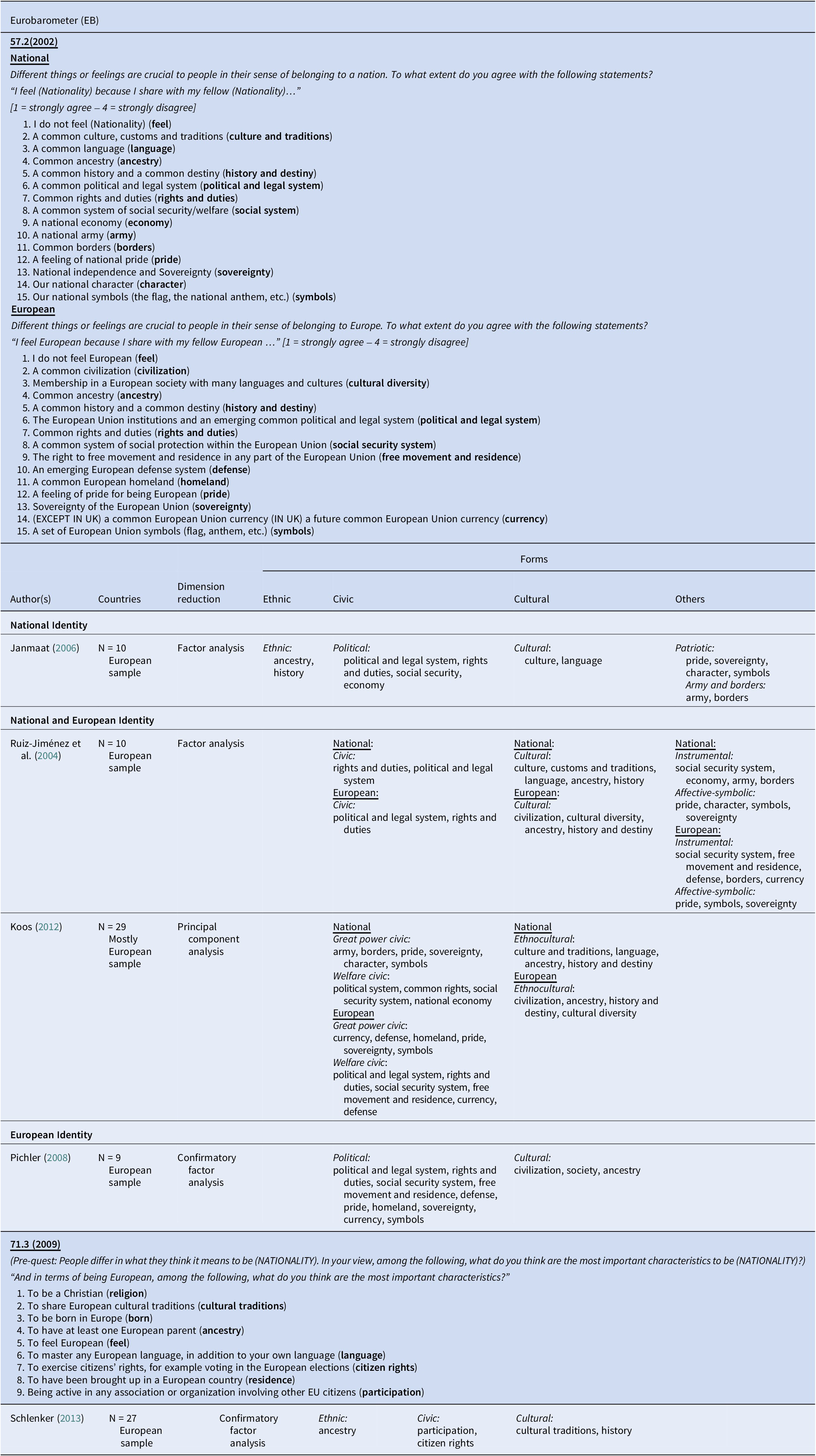

Eurobarometer

Five studies relied on Eurobarometer (EB) data. One study focused on the national level only (Janmaat Reference Janmaat2006), two of them on the European level (Pichler Reference Pichler2008; Schlenker Reference Schlenker2013), and two on both (Ruiz Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Antonia, Górniak, Kandulla, Kiss and Kosic2004; Koos Reference Koos2012) (see Table 5).

Table 5. Studies based on Eurobarometer data

Janmaat (Reference Janmaat2006) derives an ethnic, political (civic), cultural, patriotic and army, and borders form. Using the equivalent question for European identity, Ruiz Jiménez et al. (Reference Jiménez, Antonia, Górniak, Kandulla, Kiss and Kosic2004) find a cultural, civic, instrumental, and affective-symbolic form on the national and European level. Koos (Reference Koos2012) distinguishes between great-power civic, welfare civic, and ethnocultural forms on the national and European level. Concentrating on European forms only, Pichler (Reference Pichler2008) derives a political (civic) and cultural form. Based on a “true national/ European” question in EB 71.3 (2009), Schlenker (Reference Schlenker2013) finds an ethnic, civic, and cultural form of European identity.

Overall, ancestry is part of the ethnic form in both studies that include an ethnic form, whereas it is allocated to the cultural form in those without an ethnic form. Political and legal systems as well as rights and duties are a stable part of the derived civic forms.

On the European level the civic–cultural distinction is the most prominent, being supplemented by instrumental/affective-symbolic (Ruiz-Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Antonia, Górniak, Kandulla, Kiss and Kosic2004) or great-power-civic, welfare-civic, and pragmatic forms (Koos Reference Koos2012). Among others, the instrumental as well as welfare civic forms contain social security system and economy items. This indicates the relevance of socioeconomic aspects. In the instrumental approach, a distinguished form is derived—whereas the welfare-civic form merges civic with socioeconomic aspects. In contrast to the true national/European questions in other surveys, the number and variety of items seems to allow for a broader distinction of forms.

After reviewing the different approaches on measuring forms in the different international survey data, the overall core findings are summarized. Overall, even earlier studies state that the citizens across most European countries favor civic criteria (Jones and Smith Reference Jones and Smith2001) and that ethnic criteria lost relevance over time (Canan and Simon Reference Canan and Simon2019). Comparing the appearance of specific forms of national identity between Eastern and Western Europe, there is no consensus regarding whether there is an ethnic–civic gradient between those regions. Citizens of Eastern European countries often lean toward ethnic or ethnocultural national identity compared with Western European citizens in some studies (Janmaat Reference Janmaat2006; Best Reference Best2009; Ariely Reference Ariely2013; Larsen Reference Larsen, Holtug and Uslaner2021). Other studies find no clear distinction (Shulman Reference Shulman2002; Björklund Reference Björklund2006).

For European identity most studies find a civic and a cultural form (Haller and Ressler Reference Haller and Ressler2006; Pichler Reference Pichler2008). Although most Europeans give more importance to civic aspects of their European identity, some empirical results show that the cultural form is much stronger than expected (Ruiz Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Antonia, Górniak, Kandulla, Kiss and Kosic2004). Most Eastern European countries favor cultural ideas of European identity, whereas Western and Southern European countries mostly favor civic or instrumental considerations (Ruiz Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Antonia, Górniak, Kandulla, Kiss and Kosic2004; Janmaat Reference Janmaat2006; Koos Reference Koos2012).

Most of the studies operate on pooled data, albeit there are some concerns about the comparison of forms between countries. Many studies report measurement inequivalence across countries. This indicates that the meaning of specific items vary across countries and are not comparable. One strategy to face this problem is to use the least ambiguous single-item indicators (e.g., Reeskens and Hooghe Reference Reeskens and Hooghe2010) or to choose analysis methods that are person-centered such as latent class analysis (e.g., Wegscheider and Nezi Reference Wegscheider, Nezi, Bayer, Schwarz and Stark2021).

Overall, the most important insight is that single indicators are not consistently assigned to certain forms. Speaking the national language, for example, is an indicator for the cultural form of national identity in some exhibitions (Koos Reference Koos2012), whereas it is assigned to the civic form in others (Björklund Reference Björklund2006). In summary, all of these methodological concerns raise doubts about the comparability of distribution, determinants, and consequences of specific forms.

Determinants of Forms of National and European Identity

Within micro-level determinants, higher age and religiosity have a positive relation with ethnic forms across all studies. Less educated and people from lower social status also favor ethnic forms (Haller and Ressler Reference Haller and Ressler2006). In contrast, higher education, younger age, and experiences abroad are found to reduce ethnic forms of national identity (Jones and Smith Reference Jones and Smith2001; Kunovich Reference Kunovich2009). National pride (Ariely Reference Ariely2019), identification with the nation, higher levels of in-group trust, and anti-immigrant attitudes also positively correlate with the ethnic form (Wegscheider and Nezi Reference Wegscheider, Nezi, Bayer, Schwarz and Stark2021). Vlachová and Hamplová (Reference Vlachová and Hamplová2023) found no evidence that the increasing share of Muslim and immigrant population in countries influences the importance of cultural national identity.

Notably, some determinants influence the civic form similarly. Right-wing ideology and religiosity also foster the civic form of national identity (Haller and Ressler Reference Haller and Ressler2006; Guglielmi and Vezzoni Reference Guglielmi, Vezzoni, Westle and Segatti2016). Higher education and higher social status (Kunovich Reference Kunovich2009), as well as left-wing ideology (Guglielmi and Vezzoni Reference Guglielmi, Vezzoni, Westle and Segatti2016) reduce the importance of the civic form of national identity. People at higher ages tend to give higher importance to all criteria, whereas people with university degrees tend to give less importance (Jayet Reference Jayet2012). This indicates that socioeconomic differences tend to influence the overall importance of social boundaries instead of specific forms.

Only two studies concern determinants of forms of European identity. The ethnic and civic forms of European identity are both positively influenced by national and European identification, higher levels of in-group trust, and anti-immigrant attitudes. Additionally, identification with the world reduces ethnic national and European conceptions (Wegscheider and Nezi Reference Wegscheider, Nezi, Bayer, Schwarz and Stark2021).

European civility positively correlates with female gender, age, religiosity, living in small towns, right self-placement on the political spectrum, higher education, EU knowledge, and experiences abroad. In this article, a common ancestry factor for national and European levels is derived. The importance of this criterion is fostered by higher age, living in a small town, being part of the working class, religiosity, being born in the country or in another EU state, and right self-placement on the political spectrum (Guglielmi and Vezzoni Reference Guglielmi, Vezzoni, Westle and Segatti2016). Strikingly, right self-placement seems to foster an overall ethnic and civility on the national and European level alike.

The most important finding is that the same determinants on the micro level seem to foster both ethnic and civic forms of national identity alike. Generally, the more socially vulnerable (being older, lower educated, having no experiences abroad) tend to give higher importance to ethnic and civic criteria alike to narrow the in-group. In contrast, at the European level, the importance of civic aspects of European identity seems to be stronger among the more privileged citizens of Europe.

Consequences of Forms of National and European Identity

Two major branches of research on consequences could be distinguished: attitudes toward out-groups and political attitudes.

Attitudes toward Out-Group Members

Ethnic national identity fosters anti-immigrant attitudes (Kunovich Reference Kunovich2009; Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2021), negative attitudes towards Muslims (Simonsen and Bonikowsi Reference Simonsen and Bonikowski2019) and xenophobia (Janmaat Reference Janmaat2006). In most studies, civic national identity has a reducing effect on Xenophobia (Hjerm Reference Hjerm1998) and anti-immigrant attitudes (Pehrson, Vignoles, and Brown Reference Pehrson, Vignoles and Brown2009, Simonsen and Bonikowski Reference Simonsen and Bonikowski2019). However, it also shows positive relations to anti-immigrant attitudes (Janmaat Reference Janmaat2006) and xenophobia (Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2021) in some studies. Kunovich (Reference Kunovich2009) finds that a commitment to the ethnic as well as civic form of national identity is associated with restrictive sentiments concerning immigrants, preferences for assimilation, and following national interest in international politics. A preference for civic national identity is related to less restrictive sentiments for those indicators (Kunovich Reference Kunovich2009). Wamsler (Reference Wamsler2023) found that the ethnic form is a negative predictor of trust in strangers (for individuals living in more civic-oriented nations), which also applies for the civic form (although not as strong).

All in all, the theoretically assumed exclusiveness of an ethnic identity proves to be true for all research results reviewed here. However, the effects of civic national identity seem to be ambivalent.

Political Attitudes

Civic national identity correlates positively while ethnic national identity correlates negatively with trust in political institutions (Berg and Hjerm Reference Berg and Hjerm2010). Ethnic national identity fosters patriotism and nationalism, but the civic form inhibits both (Ariely Reference Ariely2020). Rating all criteria of belonging high (Exclusivists) is shown to be positively related to national attachment, general and domain-specific pride, and national chauvinism, whereas rating all of them low (Pluralist) is negatively related to them (May Reference May2023). Domm (Reference Domm2004) finds that both political and cultural national pride increase support for European integration. Emphasizing national and European ancestry reduces while emphasizing European civility increases identification with Europe (Segatti and Guglielmi Reference Segatti, Guglielmi, Westle and Segatti2016). In line with this finding, people giving low importance to all criteria of national belonging show only average EU support, whereas people with high levels of civic and low levels of ethnic connotations showed the highest support for EU (Aichholzer, Kritzinger, and Plescia Reference Aichholzer, Kritzinger and Plescia2021). One study finds that both achieved and ascribed national identity reduce support for the EU (Serriochio and Belluci Reference Serricchio, Bellucci, Westle and Segatti2016). One study demonstrates that the civic form of European identity has a strong positive, the cultural a moderate positive, and the ethnic a negative relation with cosmopolitan attitudes (Schlenker Reference Schlenker2013).

In conclusion, most articles indicate that people defining their national group in mainly civic terms tend to support the idea of the EU more than people who give importance to ethnic criteria in national identity.

Conclusion, Discussion, and Outlook

This research note reviewing literature captured cross-national studies on forms of national and/or European identity in Europe based on international surveys from 1995 to 2023. Overall, the majority of articles scrutinized forms of national identity solely, but only a few focused on the European or both levels at the same time, revealing a gap in the existing literature.

Most studies about forms of national identity empirically derived the well-known ethnic–civic dichotomy, but only a few find additional forms, such as a cultural form, when supplementing the ISSP measure with other items (Shulman Reference Shulman2002; Koning Reference Koning2011). In the few articles concerning the European level, the most common distinction relates to a civic–cultural dichotomy (Ruiz-Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Antonia, Górniak, Kandulla, Kiss and Kosic2004; Pichler Reference Pichler2008; Koos Reference Koos2012; Schlenker Reference Schlenker2013). However, in most of these articles (Ruiz-Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Antonia, Górniak, Kandulla, Kiss and Kosic2004; Pichler Reference Pichler2008; Koos Reference Koos2012) the cultural form often contains items that are typically classified as ethnic in other studies, such as ancestry. No study empirically derived a possible socioeconomic form, although some of them reveal items that might contribute to such a form. In conclusion, cultural and socioeconomic aspects seem to interweave with the more prominent approaches (e.g., welfare-civic; Koos Reference Koos2012).

Regarding determinants and consequences, the main finding is that the ethnic and the civic form are sometimes influenced in the same way by the same variables and sometimes have similar consequences, which contradicts the common expectation that both forms have different effects on political attitudes. This might be rooted in the different allocation of specific items to various forms. Another explanation could be that respondents who favor ethnic notions of nationhood do so by also embracing civic conceptions (Helbling, Reeskens, and Wright Reference Helbling, Reeskens and Wright2016). Last, the possibility that these shortcomings might be rooted in the measurement instruments has to be considered.

In nearly all articles, the true national/European battery was employed. Two major concerns can be summarized:

Concerns with the question: Most importantly, by asking about criteria of belonging, this measurement tool does not necessarily account for personal identification. It is not clear whether respondents rate the importance of specific items based on their personal affection or evaluation or according to the perceived collective importance. In countries with descent principle (ius sanguinis), the importance of having ancestry to become a citizen is structurally high—even if the ethnic component of national/European identity has no personal importance for the respondents.

Concerns with items: Another concern is the lack of measurement invariance, indicating that the items inherit different meanings across different countries. Further, the inconsistent allocation of the same items to different forms between the analyzed articles and the reported issues with cross-loadings indicate the ambivalence or two-dimensionality of some items.

Recent person-centered approaches of latent class analysis (May Reference May2023; Simonsen & Bonikowski Reference Simonsen and Bonikowski2019) try to overcome these issues. They also reveal that some respondents rank all criteria low and some rank all criteria high and that certain ideal types act similar to the ethnic–civic dichotomy by emphasizing ethnic or civic criteria over the other. This indicates that the question measures two underlying aspects. First, it measures the degree of exclusiveness respondents emphasize regarding membership criteria. Second, it measures the importance of different aspects according to ethnic and civic conceptions.

How could research improve the measurement of forms of national/European identity? Some suggestions are as follows:

-

(1) One possible way could be to move away from the rating of in-group criteria. An alternative approach might ask respondents about their own identification based on certain aspects of their country/Europe. Respondents might be asked how different aspects (e.g., “the constitution of [COUNTRY]”) affect their own attachment (e.g., increasing or decreasing it). This would allow for a clearer distinction between the personal relevance of certain aspects or the perceived collective importance.

-

(3) Existing measures should take more items into consideration that might account for additional shades of national/European identity. For example, some studies suggest the existence of additional cultural and socioeconomic forms. Some aspects seem to interweave with established forms of identity, but they could as well constitute a separate form, if enough items are integrated to allow for adequate analysis.

-

(3) Existing items should be more specific to reduce the problem of different interpretations. Items concerning language and culture are probably known as best examples (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004), as both of them can be understood in civic, ethnic, or cultural terms.

Distinguishing between ethnocultural meanings (e.g., national traditions and customs, cultural heritage) and more value-based connotations (e.g., socially liberal values) might offer a more nuanced perspective.

-

(4) Existing items should avoid carrying different stimuli. One example is the item “to respect institutions and laws,” as it could produce opposing reactions for different people because both constructs in this item can be fundamentally distinct and therefore carry different meanings. It can be associated with respect for the constitution and democracy as ideals, which seem to be indicators for a civic form—because without it, one can hardly speak of a civic identity. Yet, respondents could also associate it with the functioning of the institutions and laws, which some might evaluate as good but others might perceive as bad and therefore emphasize or reject it as a component of identity.

-

(5) A further suggestion is to separate items concerning political ideas from items concerning their realization. Respondents might identify with the principle of democratic values but not identify with the realization of them.

Even recent studies have to rely on relatively out-of-date survey data. In the most recent ISSP 2023 National Identity and Citizenship module the true-national battery has not received any innovation, but some recently included questions (e.g., concerning the possibility to become “truly [NATIONALITY],” where respondents must choose between two fictional persons with different traits) might be promising.

Only a few articles are based on cross-national data after the refugee crisis in 2015 (Wegscheider and Nezi Reference Wegscheider, Nezi, Bayer, Schwarz and Stark2021; Voicu and Ramia Reference Voicu and Ramia2021). Available surveys also lack theoretically relevant correlates. Concerning determinants, most studies rely on sociodemographic variables exclusively. Social-psychological and right-wing populism research may contribute further correlates of potential forms of national and European identity such as perceptions of distributive or procedural justice (Tyler and Blader Reference Tyler and Blader2003), the fit between the individuals’ and the groups’ values and norms (Hogg Reference Hogg2000), economic deprivation (Rippl and Seipel Reference Rippl and Seipel2018), or welfare chauvinism/ populism (van der Waal et al. Reference van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, de Koster and Manevska2010). Regarding consequences, no article was found concerning questions of social cohesion. Investigating the connections between forms of identity and solidarity between citizens of the EU or toward outward groups seems to be promising.

In summary, future research should try to overcome relying on the rating of perceived group criteria as an indicator for forms of national and European identity. Research should be encouraged to test new measurement tools that include more aspects of national/European identification and test them alongside relevant theoretical variables.

As globalization progresses and global challenges arise, one necessary step is to understand what constitutes feelings of togetherness. Being able to empirically capture the complexity of national and European identity might be a cornerstone to comprehend under which conditions social cohesion emerges.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their valuable feedback. Special thanks go to Prof. Dr. Bettina Westle and my other colleagues of the EUNIDES project for their support on writing this article.

Disclosure

None.

Financial support

This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF)).

(Grant number: 01 UG2111).