Introduction

In a post-communist country that is still undergoing processes of democratization and where there is an oversaturation of media outlets, the media’s economic survival often depends on its political relationship with the state. In this regard, the government intervenes in the media through direct ownership or through indirect mechanisms of control, such as financing from the state budget, including advertising and vis-à-vis project co-financing. The media is then expected to promote the government’s work and publish positive news coverage of the leading political elites in power. Serbia represents a prime example of this case, where the media market is small and thoroughly oversaturated with many media outlets, the majority of which depend on government financial support as the key basis for their sustainability. Ryabinska (Reference Ryabinska2011) argues that in Serbia and some of its Balkan neighbors, the media “are not autonomous from governments or vested interests, but highly dependent on them, and they function not as democratic institutions, but as tools for trading influence and manipulating public opinion in the interests of power-holders” (4). As a consequence, powerful elites such as Aleksandar Vučić in Serbia will adopt authoritarian policies toward the media, thereby contributing to the decline in freedom of expression, where the media outlets serve as powerful PR for the Serb President and leading party officials.

We argue that due to the limited scope and nature of what constitutes media independence and pluralism, in addition to the lack of EU competences to instigate media freedom reform in some of its own Member States, has given Serbian politicians a margin for maneuver to manipulate basic norms and values in a manner that would serve their own interests. The EU does not have clear criteria for defining media freedom as it is not part of the acquis and exists solely as benchmarks for the negotiating chapters pertaining to freedom of expression, which include Chapter 23 on Justice and Fundamental Rights and Chapter 10 on Information Society and the Media. Given the difficulty in defining media independence and pluralism, we refer to the EU’s benchmarks as the basis of our analysis. Freedom of expression conditionality from Chapter 23 posits that Serbia respects independence of the media through “the application of a zero-tolerance policy as regards to threats and attacks against journalists… transparency (including on ownership of media), integrity and pluralism” (Conference on Accession to the European Union-Serbia 2016, 28). In these benchmarks, there is no mention of state withdrawal from the media, let alone limiting the state funding of the media. From an interview conducted with a former official from the EU Commission, we learned that media that is free from political influence and control is the core principle of media independence (EU Commission Official Y 2016).

To meet the EU conditionality on media freedom and thus bring the media environment up to European standards, the Serbian government adopted three laws – public information and the media, electronic media, and public broadcasting services – in August 2014 (B92 2014). Despite the adoption of the new media laws, Serbia has achieved very little progress in reforming the media sector, and significant state interference in the media persists. Political influence has had a negative effect on the media, especially through the continued financing of media outlets through indirect means such as project co-financing and state advertising. The EU Commission progress reports (2021, 2022) have also developed a critical stance toward the media environment in Serbia, stating “limited progress” had been made in “adopting and starting to implement a limited number of measures under the action plan related to the media strategy” (European Commission 2021a, 17–18). The previous media strategy initially adopted under the Democratic Party government in 2011 expired in 2016 with a new one established under the current President Aleksandar Vučić, leader of the Progressive Party, on January 30, 2020. Although it has been cited by journalists’ and media associations as a “brilliant success,” the EU Commission report (2021) argued that cases of threats, intimidation, and violence against journalists were still a source of serious concern while political and economic influence over the media continued to persist, particularly through project co-financing and advertising, which often offered public funds to media in close association with the ruling party and those who violate the journalistic code. Furthermore, although the privatization process has been completed, much of the media outlets continue to be influenced by the ruling party either through ownership structures or financing mechanisms.

We argue that the adoption of the three new media laws and the government’s action plan for their implementation was, in reality, a means to convince the EU on paper that Serbia was complying with conditionality stemming from Chapter 23 for the sake of advancement in the EU accession negotiations. By simulating EU-compliant change in the short run while seeking ways of reversing that change and maximizing profits in the long run, Serbian politicians were engaging in fake compliance. Noutcheva (Reference Noutcheva2006) argues that “if domestic actors pass legislation compliant with EU demands but legal enforcement does not follow up, and problems of technical nature are not obvious, the ensuing conclusion is that there is no political will to do the reforms requested. Hence, the actors do not believe in the appropriateness of these domestic changes” (11). A lack of political willingness on the part of Serbian political elites, in addition to limited EU competences, has not contributed to a conducive environment in which the media remain free from political influence.

This article examines the worsening media situation in Serbia dominated by the clientelist relationship between media outlets and Serbian political elites, predominantly those of the ruling Progressive Party. It will measure domestic compliance to EU conditionality through a comparative analysis of EU benchmarks stemming from Chapter 23 and the implementation record of Serbian media laws and the newly adopted Action Plan, supplemented by journalists’ association reports. By examining the Law on Public Information and the Media, we will argue that a lack of EU benchmarks has led to the continued state intervention of the media at all levels. The article will focus predominantly on ownership structures and non-transparent sales and project co-financing, where the Serbian government continues to maintain its political influence. We will also analyze the threats and attacks on journalists, another critical EU benchmark. We argue that the adoption of the media laws and action plan for their implementation were strategies the Serbian government used to persuade the EU of their compliance on paper. In reality, implementation was limited, and the media laws did not lead to greater transparency or state withdrawal from the media, including in financing and ownership, which posits a strategy of fake compliance. We conclude with a discussion on the credibility and clarity of EU competences in the area of media freedom, arguing that in the absence of clear conditions and acquis, media freedom decline is in the eye of the beholder, allowing room for Serbian elites to exploit EU demands to serve their own interests due to the gap between public engagements with Serbian officials, including in EU measures to drive domestic-compliant change, and the critical EU Commission progress reports.

Theorizing the Impact and Effectiveness of the EU’s Rule of Law Conditionality in the CEECs and the Western Balkans

The EU has put human rights at the core of its enlargement policy since the introduction of the Copenhagen criteria in the enlargement process in 1993, which first became applicable to the Central and East European countries (CEECs). However, Kmezić (Reference Kmezić, Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2018) argues that regarding the CEECs, the European Commission defined its political criteria as far as back as its 2000 Agenda, mainly pertaining to the rule of law and fundamental rights, including freedom of expression (94). While many scholars (Prîban Reference Priban2009, 350; Grabbe Reference Grabbe2014; Ganev Reference Ganev2013, 32) argue that the EU’s transformative power had an overall positive impact on the democratization of the CEECs, recent shortcomings and democratic backsliding in the post-accession phase in the CEEC members and the Balkan candidates suggests that the effectiveness of EU rule of law conditionality was marginal and, according to Leino (Reference Leino2002), lacking any “actual substance.” Member States such as Hungary, which were models during the accession process, have now lapsed into a complete reversal of democratic practices, especially evident in Prime Minister Orbán’s one-party colonization of the media sector (Bajomi-Lázár Reference Bajomi-Lázár2013). Following the failure of political conditionality in the CEECS, the EU sought a “new approach” regarding the prioritization of the rule of law reforms in the Western Balkan candidates early on in the accession process and the introduction of an interim benchmarking system for Chapters 23 and 24 in order to “learn the lessons of the previous enlargements and to avoid having to initiate a Cooperation and Verification Mechanism after accession” (Kmezić Reference Kmezić, Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2018, 95). Moreover, Hillion (2018) argues that “the possibility was provided for Member States to suspend the whole negotiation process if they could see problems regarding the rule of law chapters” (cited in Huszka Reference Huszka2018). This approach became first applicable to the Western Balkan countries, but, once again, it failed to trigger the necessary reforms concerning the rule of law. While all the Balkan candidates suffer from substantial shortcomings when it comes to rule of law, Serbia serves as a prime example when it comes to violations of freedom of expression – a basic human right seen by the EU as one of the most significant cornerstones of democracy.

Very limited attention has been paid to the EU rule of law conditionality in Serbia, particularly regarding the analysis of freedom of the media. Huszka’s (Reference Huszka2018) article offers an analytical approach to the failure of the EU’s transformative power in the Western Balkans, focusing on rule of law in the Western Balkans, arguing that the EU was mainly concerned with prioritizing regional stability and security while sidelining other human rights issues, predominantly those pertaining to media freedom. This is also echoed in Vachudova’s (Reference Vachudova2014) study on the effects of EU leverage and democratization ten years after the EU’s first dramatic wave of accession between 2004–2007 in which she argues that “fears of instability in the Western Balkans have made the EU especially keen to apply its leverage there, while recent setbacks have underscored the importance of using more extensive and consistent conditionality well before accession” (134).

Kmezić’s (Reference Kmezić, Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2018) study on the transformative power of the EU’s rule of law conditionality, using media freedom in Serbia as a mini case study is the first to address the EU side of the conditionality-driven bargaining game regarding freedom of expression in Serbia. Through a brief analysis of the obstructionist policies of Serbian gatekeeper elites to democratic reforms in the area of media freedom, Kmezić (Reference Kmezić, Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2018) argues that this “fake compliance” or even non-compliance with EU rule of law conditionality can mainly be attributed to the EU’s lack of credibility and clarity to media freedom conditionality. Additionally, he argues that on the domestic side, legacies of the past have also played a substantial role in Serbian elites’ ability to engage in fake/non-compliance.

We argue that in the absence of clear and credible conditionality or benchmarks, what constitutes the serious degradation of the media freedom is in the eye of the beholder as it is not always clear cut, particularly if the decline has been gradual over time as is the case in Serbia. The Central and East European countries that were models during the accession phase and saw improvements in media freedom in the 1990s and 2000s have since lapsed into democratic backsliding, especially in Poland, Slovenia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary. The EU does not have much leverage in the post-accession phase to enforce compliance in Member States: while the EU used sizeable (conditional) rewards, most notably the golden carrot of membership, after accession, EU institutions can only use negative incentives – sanctions (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Reference Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier2019, 6). Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier (Reference Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier2019) argue that “the autonomy of EU institutions in deciding on sanctions is extremely limited: the member states themselves determine by unanimity (minus one) whether such a breach has occurred” (7). A notable example of the limits of EU leverage in the post-accession period where the EU lacked credibility in punishing Member States for abuses in the rule of law is the case of the Fidesz-led Hungarian government, which adopted a new Fourth Amendment that went against constitutional rights and basic democratic values. Regarding freedom of expression, including in independence of the media, “the amendment created a constitutional ban on political advertising during the election campaign in any venue other than in the public broadcast media, which is controlled by the all-Fidesz media board” (Scheppele Reference Scheppele, von Bogdandy and Sonnevend2015, 121). This was a measure to prevent opposition parties from political advertising and reporting on other, more independent media outlets and a means to control election campaigns.

Upon the request of the European Parliament, its Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) prepared a report on the Hungarian constitutional situation, including the impacts of the Fourth Amendment on the Fundamental Law of Hungary. On 3 July 2013, the report passed with a surprisingly lopsided vote: 370 in favour, 248 against and 82 abstentions. (Halmai Reference Halmai2019, 4)

Even though the report had passed, the sheer number of EU MEPs who had been against the report demonstrates that voices in the EU are mixed when it comes to determining the decline in rule of law in both Member States and candidates. Regarding the deteriorating state of the media in the Western Balkans, predominantly in Serbia, there is an overall lack of will on behalf of the EU to punish or publicly “name and shame” Balkan leaders, such as Vučić in Serbia, who are responsible for democratic backsliding. Instead, the EU appears to be rewarding Serbia for fake compliance while the critical Commission progress reports do not resonate with public statements and engagements with Serbian officials, creating a communication gap which Serbian elites can exploit to their advantage, allowing them to continue to engage in fake or even non-compliance. Moreover, the EU’s “double standards” in essentially rewarding Serbia despite fake compliance through the opening of accession chapters has given Serbian elites opportunity to exploit the EU’s ambiguous conditionality. Since 2019, the EU Commission has opened an additional two chapters: Chapter 9: Financial Services and Chapter 4: Free Movement of Capital. Thus far, the EU has opened 22 out of 35 chapters with two chapters being provisionally closed. In addition, Brussels continues to provide financial and technical assistance to the Western Balkan governments through the Instrument for Pre-Accession (IPA), to transpose (on paper) the EU acquis, which has not led to norm adoption and internalization but to shallow Europeanization (Zweers Reference Zweers and Cretti2022, 13).

Data and Methods

The literature pertaining to Serbian government influence in the media sector is marginal and limited; thus, much of our analysis stems from journalists’ reports and press releases published by journalists’ associations, the Belgrade Center for Human Rights, and EU progress reports. We primarily examine and focus on the government’s Action Plan for Implementation of Chapter 23 on Justice and Fundamental Rights. This will address the interim benchmarks outlined in Chapter 23 Serbia is required to comply with to become a fully fledged member of the EU. The Action Plan for Chapter 23 will focus on the criteria for the implementation of the newly adopted Media Strategy 2022–2025 and will be compared with EU benchmarks in addition to reports from the EU Commission and journalists’ associations on the state of the media in Serbia to test our hypothesis that Serbian elites are engaging in fake compliance with media freedom conditionality. The article is therefore split into two sections analyzing how the Serbian government has demonstrated fake compliance regarding media freedom conditionality by examining the government influence in the media through ownership structures, financing of the media through project co-financing in addition to other means of government control, followed by an analysis of the increased number of attacks and threats against journalists. The final section discusses the lack of EU competences in both the acquis and benchmarks, which allows for mixed interpretations of what constitutes media freedom and degradation of freedom of expression in Member States and candidates, thereby enabling Serbian domestic elites to exploit EU conditionality.

Ownership Structures and State Financing of the Media

One of the most evident ways political elites can influence media outlets, including editorial policy, is through means of direct ownership – media that the government either owns fully or holds a certain portion of shares thereof. Although the Serbian 2006 Constitution posits that all types of ownership are equal, which suggests that the government would thus be allowed to own a media outlet, much of the media owned by local municipalities and the state were often used as propaganda machines in the hands of political elites (Barlovac Reference Barlovac2015, 1). The EU had pushed for years the independence of the media through its enlargement strategy reports. Therefore, the Law on Public Information and the Media, adopted in August 2014 by the Serbian government, prescribed mandatory privatization of all media that is in “full or predominantly in public ownership and which are wholly or predominantly funded from public funds” (Službeni Glasnik 83/Reference Glasnik2014). The Law also prohibited further funding of the media from public revenues after July 1, 2015 (Službeni Glasnik 83/2014). As planned, almost all of the former state-owned regional media outlets in Serbia have been privatized since 2015, with the major Serbian print dailies Politika and Večernje Novosti being recently privatized in 2022 and 2021, respectively. Moreover, out of 73 public media, 34 were privatized; “14 were bought by pro-SNS entrepreneurs, who recouped the costs through grants provided by SNS-controlled local authorities” (Castaldo Reference Castaldo2020, 15). Instead of weakening the government’s grip on the Serbian media vis-à-vis privatization, control of the media by the Progressive Party has increased noticeably. The majority of the media outlets had been purchased by business tycoons with ties to the ruling party, such as Radoica Milosavljević who bought fourteen media outlets and whose media continue to receive large amounts of money during the calls for competitions in project co-financing. In addition, state and local government funding is systematically used to finance the loudspeakers of power close to them while independent media and those critical of the ruling party have almost no chance at receiving any type of fundingReference Glasnik.

According to a report published by the Belgrade Center for Human Rights in 2021, “many local self-governments, as well as republican authorities, continued with their practice of funding media via public contracts concluded for other reasons as well, thus indirectly influencing their editorial policies through covert subsidies” (Belgrade Center for Human Rights 2021, 110). One of the most drastic examples was that of Tanjug news agency which continued to operate until March 2021, despite being officially shut down in a government decision in 2015. Its trademark was purchased by a pro-government outlet along with companies owned by Željko Joksimović and Manja Grčić, both of whom are known for their affiliation with the ruling party. Tanjug also received 15 million RSD for concluding contracts with the Serbian government ministries for media coverage or “advertising” on their activities (Belgrade Center for Human Rights 2021, 110).

Another drastic and controversial example of state funding is the case of Telekom Serbia, the 78 percent state-owned cable and broadband provider. Telekom Serbia has been used as a political tool for the Progressives and Vučić to expand his media monopoly and stifle critical voices from opposition media in a move to control editorial policy. Telekom Serbia’s main rival is that of the more independent network Serbia Broadband (SBB). “According to the Regulatory Agency for Electronic Communications and Postal Services’ data, SBB held 45.6% of the market of media content distribution in the first quarter of 2021, while Telekom Serbia, with its provider Supernova, which it acquired in the meantime, held 45.4%” (Čačić Reference Čačić2021). Over the past three years, Telekom has spent exorbitant amounts for the acquisition of smaller cable channels, such as Kopernikus, Telemark, AVCom, and Radijus Vektor, elucidating the fact that their decisions to buy out opposition networks as politically motivated and backed by the ruling party. Among the most controversial purchases was that of Kopernikus in 2018 for around €200 million from a businessman (Srdjan Milanović) close to the Serbian Progressive Party, who shortly afterwards bought TV channels Prva and B92, turning them into pro-government outlets (Čačić Reference Čačić2021). Telekom also purchased the broadcasting rights to English Premier League matches in six seasons for an estimate of €600 million (Čačić Reference Čačić2021). All of these political maneuvers were seen as efforts to destroy the competition with SBB – the most drastic move being Telekom’s merging with Telenor to reduce its market share in the distribution of media content to silence the opposition channels and prevent citizens from being informed from multiple sources, which in turn also prevents media pluralism.

The newly adopted Action Plan for the Media Strategy 2022–2025 calls for preventing media control based on excessive dependence on state advertising, strengthening media pluralism, and further strengthening the transparency of media ownership. The benchmarks in the action plan which directly refer to state intervention and control in the media are “3.3.2.11: establishing a regulatory framework in the field of public information and advertising by public authorities and companies owned or financed mainly by the state” and “3.3.2.12: Effective monitoring of the implementation of tax relief and other forms of state aid that is a possible source of influence on media independence.” Both are stated as being “successfully implemented.”

The Action Plan envisages that after conducting an analysis of the regulatory framework in the field of advertising, with special reference to the problems related to advertising of public authorities and companies that are owned or financed by the state, propose or submit an initiative to adopt new or amend existing regulations, as a precondition for creating a level playing field for all media. (Government of Serbia 2022a, 165–166)

The most recent, revised report notes that “this analysis of the regulatory framework in the field of advertising is underway” and that “a working version of the Draft Law on Amendments to the Law on Public Information and Media has been prepared, comprising two parts – one in which members of the Group reached an agreement on and the other where no consensus was reached” (Government of Serbia 2022b, 560). For activity 3.3.2.12 regarding other forms of state aid that contribute to excessive state interference in the media, “the Ministry of Culture and Information monitors the registration of data on granted state aid within the existing regulations” (Government of Serbia 2022a, 166). However, there are numerous shortcomings regarding the scope of reporting funds allocated to media publishers, as well as insufficiently efficient systems for monitoring compliance with legal obligations (Government of Serbia 2022a, 166).

The benchmarks for Chapter 23 make no mention of the withdrawal of the state from the media, including in ownership from the media and financing. The recommendations for Chapter 23, however, posit, “implementation of the media strategy with a view to appropriately regulating state funding and putting an end to control of media by the state” (European Commission 2013, 38). However, these recommendations have no legal basis, unlike the interim benchmarks, and thus allow Serbian elites a margin of maneuver to manipulate EU norms and values in order to gain political points among their electorate.

A Serbian journalist from the Journalists’ Association of Serbia claims that while the privatization process had slowly started to phase the state out of some of the media, the Serbian government has recently found new ways to gain access and control through the use of the broadband and cable network provider Telekom Serbia, which has accumulated and created various channels for exorbitant amounts of money in order to destroy competition (Journalist B, Journalists’ Association of Serbia 2022). Furthermore, even with a change of power in the future, there is very little possibility that the government will relinquish control over the media, given past nationalist and authoritarian legacies (Journalist B, Journalists’ Association of Serbia 2022).

Project Co-financing

To persuade the EU that the Serbian government is complying with EU conditionality, the new law on project co-financing as a permissible form of state aid to replace state subsidies was adopted, coupled with the government action plan for its implementation. The purpose of the law was to monitor project co-financing and allow for media outlets to receive state aid in a transparent, non-discriminatory manner for projects whose content met the public interest. According to Sejdinović and Medić (Reference Sejdinović and Medić2021),

the main point of media reform was the establishment of a system of project-based co-financing of media content of public interest, which includes legal definition of public interest, a procedure for allocating funds and independent commissions composed of media experts or representatives of journalists’ and media associations. (14)

It was believed that this system would have provided Serbian citizens with significantly more quality media content, which was also free from political interference.

According to the Action Plan Report for the first quarter of 2022, the Ministry of Culture regularly submits reports on project co-financing, asserting that this activity is being successfully implemented. However, the EU Commission Progress Report for Serbia (2021) states that “the existing guidelines for media co-funding require an assessment of whether participants in the call for proposals have had measures imposed by state bodies, regulatory bodies, or self- regulatory bodies due to violation of professional and ethical standards” (European Commission 2021a, 36). It also posits that “the print media with the most violations of the journalistic code of professional conduct recorded by Serbia’s Press Council continued to receive public co-funding, especially at the local level” (European Commission 2021a, 36). In the revised and newly published 2022 progress report, the Commission noted that amendments to the Law on Public Information and the Media, which would include public co-financing, have started being drafted but that consultations were put on hold and are now long overdue, in addition to delays in the quarterly monitoring reports (European Commission 2022, 39). The critical stance of the EU regarding project co-financing suggests fake compliance despite the adoption of the new law in August 2014. The Serbian government claims that public authorities regularly prepare and submit reports on the co-financing of media projects, but these reports remain superficial and do not reflect genuine compliance in reality. In this regard, project co-financing, which was supposed to ensure media independence and pluralism through financing of media projects in a fair and transparent way whose content met the public interest, was still used to award large sums of money to pro-government media.

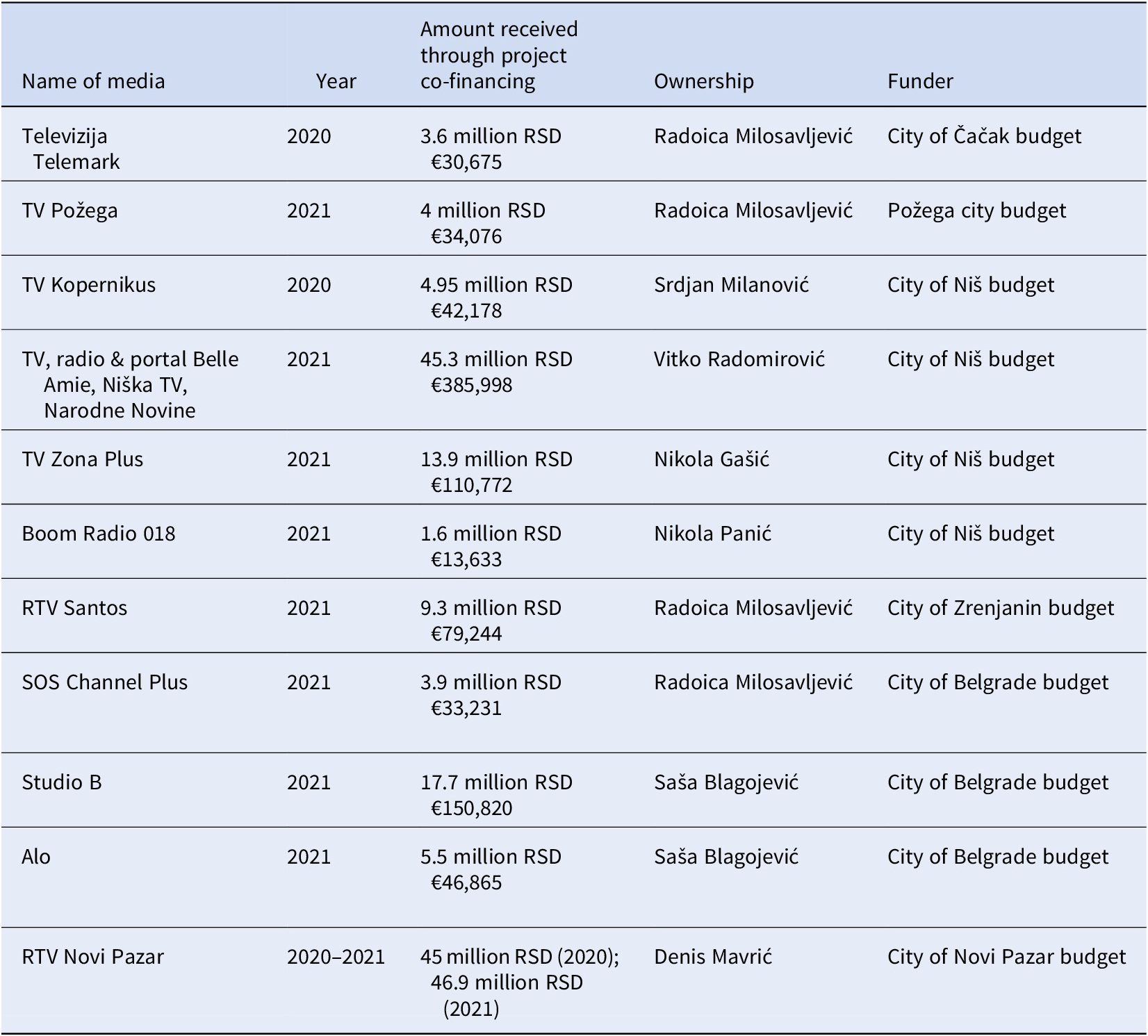

The biggest winners in project co-financing competitions were media that were “very close to the ruling party” in terms of editorial policies or ownership structures. Table 1 demonstrates a few examples of the media outlets connected to government officials that received the greatest amounts of money through project financing competitions for the years 2020–2021. SOS Channel Plus, RTV Santos, TV Požega, and TV Telemark are privatized media owned by Radoica Milosavljević who is affiliated with the Socialist Party of Serbia. During the privatization process, Milosavljević purchased eight media outlets in Serbia: RTV Kruševac, RTV Kragujevac, TV Pirot, RTV Brus, Centar za informisanje Novi Kneževac, TV Požega, RT Dimitrovgrad, and RTV Pančevo. He is also one of the biggest donators and supporters of the Serbian Progressive Party (Kostić Reference Kostić2019). From 2015 to 2020, thirteen of his media companies received €3.1 million (Aleksić Reference Aleksić2021; Obrenović Reference Obrenović2021).

Table 1. Results of Project Co-Financing Competitions in 2020–2021

(Source: Torović Reference Torović2020; Danas 2021; Ljubičic Reference Ljubičić2020; Djurić Reference Djurić2021; Pudar Reference Pudar2021; Obrenović Reference Obrenović2021)

TV Kopernikus is owned by Srdjan Milanović, the brother of a high-ranking SNS official (Cuckić Reference Cuckić2020). Finally, Studio B is newly owned by Saša Blagojević who also owns the pro-government tabloid Alo. Both Studio B and Alo are pro-regime media outlets that support the ruling party (Nedeljković and Jovanović Reference Nedeljković and Jovanović2020, 18). Additionally, he is also a friend of the Minister of Finance Siniša Mali (Nedeljković and Jovanović Reference Nedeljković and Jovanović2020, 20). TV Zona Plus’s ownership is still in the hands of the Gašić family, also functionaries of the SNS. Denis Mavrić who owns RTV Novi Pazar is affiliated with Rasim Ljajić, whose party is in a coalition with the ruling SNS.

Tabloids close to the authorities also received the greatest amounts of money in the calls for competition in project co-financing during the COVID-19 state of emergency. The Journalists’ Association of Serbia (UNS) published an analysis according to which in the first five months of 2020, Alo, Kurir, Srpski Telegraf, and Informer received slightly fewer than 26 million RSD at local public calls. According to the Press Council, these same media outlets violated the Code of Ethics of Journalists of Serbia as many as 3,900 times in the second half of 2019 (Sejdinović and Medić Reference Sejdinović and Duško2020, 19).

This political influence, as shown in Table 1, demonstrates unfair and non-transparent allocation to certain media outlets that are close to the ruling party. Discriminatory allocations to favored media continued, thus promoting media content where the government was allowed to interfere in the production of content and editorial policy and use it for their own personal and political party needs. A journalist from the Independent Journalists’ Association of Vojvodina argues that “the problem is that they abuse the laws so that the money is allocated to their media; in the Commission, they put people who are loyal to them, and the whole process cannot be controlled by anyone on the outside” (Journalist A from the Independent Journalists’ Association of Vojvodina 2016). Therefore, the entire process becomes non-transparent as the same journalist once again argues: “if in the Commission, there are no members of the press and media associations, we do not know what the content of the project is, and we especially do not know how it has been carried out and for what funds have been spent” (Journalist A from the Independent Journalists’ Association of Vojvodina 2016).

To conclude, project co-financing, although changed and now defined in the Law on Public Information and the Media, has so far not promoted independent media that are free from political interference. Media that have been favored by the government and whose new owners are connected to the ruling Progressive Party received greater amounts through project co-financing as opposed to smaller, independent media or media critical toward the government. Tanja Maksić, a journalist from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, claimed that this affects the poor quality of reporting and that there is no media pluralism, which should be the basic feature of the media system, with more sources and topics (Fonet 2022). The pro-regime media and those whose ownership structures are close to the ruling party were expected to report on the work of self-government and promote a positive image of Aleksandar Vučić and the Progressive Party. In this regard, “in many cases, project-based co-financing has essentially turned into payment for marketing services, i.e., media financing for the sake of uncritical promotion of the activities of government representatives, which is deeply inconsistent with the goal and significance of media reforms” (Sejdinović and Medić 2020, 19). In addition, most of the financing often went to pro-government tabloids who continuously violated the journalistic code of ethics. The Europeanization literature on the degree of domestic change in project co-financing, as stipulated by the Law on Public Information and the Media, indicates that the degree of domestic change was low. The Serbian government merely “absorbed” the media law into their domestic structures without modifying existing processes and policies. As a result, political interference via project co-financing and discriminatory as well as non-transparent funding allocations to media outlets continued, despite the adoption of the new law and the government’s action plan for its implementation.

Safety of Journalists

The European Commission Progress Report for Serbia (2021) claimed that violence and threats against journalists continued, while “most media associations withdrew from the group on the safety of journalists in March 2021, citing hate speech and smear campaigns against journalists and civil society representatives, including by the head of the ruling party caucus” (European Commission 2021a, 34). Other reports by journalists and the Media Sustainability Index (IREX) have also published figures on the number of attacks and threats against journalists in 2020 and 2021. The IREX reported that, “for the first time in two years, several journalists were arrested, and 189 attacks on journalists were registered, of which 32 were physical attacks and 14 were attacks on journalists’ property” (IREX 2021). The increase in the number of incidents against reporters and media in 2020, corroborated by the data of the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia, was particularly concerning. “The safety of journalists was threatened 186 times during the reporting period; 32 of these assaults were physical” (Belgrade Center for Human Rights 2020). According to the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia, in another report, “in the period from the introduction of the Covid-19 state of emergency on 15 March to 6 May, a total of 47 cases of incidents against journalists were recorded. Among them, there were 32 cases of pressure and 15 cases of various forms of attacks on journalists. Of the 15 attacks, there were two threats to life, two detentions as a form of physical threat to journalists, seven verbal threats, two physical attacks on journalists, and two attacks on property” (Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia 2021a, 10). These numbers relating to the attacks and threats to the safety of journalists did not diminish following the state of emergency and the pandemic; rather they seemed to worsen. The safejournalists organization published a comparative analysis in 2022 where it compared figures from 2021 to 2020 for all the Western Balkan countries. In the report, it claimed that in Serbia there were 33 threats to the life and physical safety of journalists in 2021, as opposed to 15 in 2020. There was also an increase in the number of attacks and threats to media organizations, from 4 in 2020 to 11 in 2021. The number of actual attacks on journalists had, however, decreased, from 28 in 2020 to 5 in 2021, but, according to the report, this does not mean that the situation regarding journalists’ safety is relaxed (Trpevska and Micevski, Reference Trpevska and Micevski2022, 47).

According to both the EU progress report and the latest implementation report, there has been an increased number of actions taken by the Prosecutor’s Office and the Ministry of Interior to better ensure the safety of journalists, including in the number of cases filed, the number of meetings organized by the Standing Working Group, the decision made to act urgently in cases of criminal offences committed to the detriment of journalists, as well as the increase in the number of contact points. However, according to the data presented by journalists’ associations and the EU, it is clear that Serbian political elites are once again engaging in compliance on paper, without implementing the necessary reforms needed to ensure the protection and safety of journalists. The Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia (2021) reported that

only in the first eight months of 2021, out of 55 registered cases of attacks on journalists, in 16 of them a decision on dismissing criminal charges was made or a formal note was made that there were no elements of a criminal offence, while such a decision or formal note was made in 24 cases out of 57 filed in 2020. (Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia 2021b, 11)

The EU Progress Report (2021) similarly corroborated this fact:

According to the Republic Public Prosecutor’s Office’s (RPPO) information regarding those acts that qualify for criminal prosecution, by the end of December 2020, out of the 55 cases filed in 2020, 37 cases were considered by the RPPO and 18 cases were dismissed. Altogether, three cases (three convictions in court) were finalised, while criminal proceedings continued for the 34 remaining cases. (European Commission 2021a, 35)

The Belgrade Center for Human Rights (2021) report claimed that “by the end of October 2021, prosecutors formed 66 cases concerning the safety of journalists, a third of which were dismissed. Only six convictions were handed down in 125 such cases formed in 2020 and 2021 (Danas 2021). In an interview with a journalist we conducted, it was stated that “the Serbian government gives the illusion that they are working on cases for the safety of journalists by dismissing them on the ground that there is no criminal charge” (Interview with Journalist B, Journalists’ Association of Serbia 2022).

While actions toward the protection and safety of journalists have been taken, compliance remains superficial due to an insufficient number of resolved cases and a lack of efficiency in resolving them, indicating once more that the degree of Europeanization was low.

Soft Power Instruments? The Limits of EU Competences in Rule of Law Conditionality

The EU’s position regarding the conditionality pertaining to media freedom is rather complex, as there exists no official law that would instigate media freedom reform in EU Member States and in the applicant countries. Media regulation is in the hands of Member States to implement, leading to significant variations in the form and level of media regulation (Harris Reference Harris2013). This lack of capacity therefore raises questions about the competences of the EU in the area of media freedom. Moreover, the independence and pluralism of the media are often contested in both nature and scope due to the apparent lack of definition in the EU’s acquis. Referring to Kmezić’s (Reference Kmezić, Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2018) study on the Serbian government response to EU demands vis-à-vis media freedom, it is this lack of clear and credible conditionality linked to the EU’s limited competences that allows for the Serbian domestic elites to engage in a strategy of fake compliance, exploiting this ambiguity to suit their own political or party needs. Developing from Kmezić’s (Reference Kmezić, Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2018) argument, we posit that in the absence of clarity and credibility in the EU’s conditions and the acquis, the decline in media freedom and what constitutes freedom of expression is in the eye of the beholder, which is not always transparent. We elucidate this by first offering an analysis of the EU acquis followed by the specific benchmarks in Chapter 23 on Justice and Fundamental Rights that refer directly to freedom of expression. Then. we conclude with a discussion on the mixed statements made by EU officials on the state of media freedom in Serbia and the discrepancy between public engagements with Serbian officials and EU progress reports, which creates a communication gap which the Serbian government can exploit.

The EU’s acquis is categorized into 35 chapters in the accession negotiations; Chapter 23 on Justice and Fundamental Rights and Chapter 10 on Information Society and the Media are the two chapters that would have the most impact on media freedom. Each chapter focusing on a specific policy area in the accession negotiations comes with a specific set of conditionality, or interim benchmarks, that an applicant country must comply with to proceed further down the path toward accession. Thus far, we have examined and analyzed the conditionality from Chapter 23, for Serbia. Chapter 10 does not have yet interim benchmarks; thus, it has been left out of the study.

All accession countries and Member States have adopted their own legislation pertaining to the freedom of the media to respond to EU conditions. For Serbia, these domestic media laws were adopted in August 2014 and were included in Serbia’s Action Plan for Chapter 23. According to an official from the EU Commission,

The [accession] procedure not only looks at if the [media] laws have been adopted but also looks into their effective implementation. Thus, the EU does not close chapters. First, the government has to adopt the law; second, it has to build the capacity to implement the law and then establish a track record of implementation. (European Commission Official W 2015)

The acquis chapters and the interim benchmarks are tailored specifically to each accession country. Regarding Serbia, Chapter 23 on Justice and Fundamental Rights mentions the following interim benchmarks the country needs to meet to proceed to the next phase in the accession negotiations: “full respect for independence of the media, a zero-tolerance policy as regards to threats and attacks against journalists,” as well as “creating an enabling environment for freedom of expression, based on transparency (including on ownership of the media), integrity and pluralism” (Conference on Accession to the European Union-Serbia 2016, 28).

While an independent media implies media that is free from political influence, the benchmarks make no mention of state intervention in the media, which would include state withdrawal and regulation of media financing. Moreover, although the conditionality in Chapter 23 mentions ownership transparency, this does not account for transparency in financing. The conditions for independence and pluralism of the media, which would include media that are free from political intervention, form part of the political criteria applicable to all accession countries. However, we argue that the conditionality pertaining to freedom of expression are complex and open to interpretation. According to an official from the EU Commission, “a lot of what is in the political criteria is not based on texts, but it is more based on an understanding which is very open to interpretation” (European Commission Official X 2015). The same official from the EU Commission additionally claimed, “I think we are on quite dodgy ground making some of those recommendations given what happens in our own Member States” (European Commission Official X 2015). Serbia, along with other accession countries, must align its own domestic laws with those of the EU’s legislative corpus, the acquis, or in other words, adopt and implement the acquis. However, based on our findings, state intervention, including financing and ownership, are not part of the acquis. The European Parliament notes the following:

The acquis that is specifically relevant to the media sector and to media freedom is mostly associated with the processes of liberalisation and harmonisation of the internal market at the EU level and refers only indirectly to media freedom and pluralism. They follow long-established internal EU policies on media freedom and pluralism and, therefore, the newly shifted focus is reflected only in an indirect manner, that is, it is not included explicitly in the acquis. (European Parliament 2014a, 41)

We argue that this has a real effect on the capacity of the EU to spur reforms in the media sector, both in its own Member States and in candidate countries such as Serbia. This effect has been observed in various EU documents that are part of the accession process with Serbia, including through a lack of detailed benchmarks, a lack of deep analysis, fragmentation, and sections devoted to the issue being relatively concise and/or general (Bajić and Zweers Reference Bajić and Zweers2020, 18). Out of the 50 benchmarks, only two are devoted to freedom of expression while the rest are devoted to the fight against corruption and the judiciary. Moreover, the EU accession reports, which are the most visible signs of Serbia’s progress, also suffer from a lack of detailed analysis. Issues pertaining to media freedom, such as political interference and violence against journalists, have all been addressed but without much detail on how they should be resolved (Bajić and Zweers Reference Bajić and Zweers2020, 18). The lack of overall clarity in EU conditionality undermines the whole process of enlargement; this is because in the absence of a clear and credible criteria, the EU fails to monitor and simulate domestic-compliant change regarding the rule of law.

Credibility refers to the consistent use of instruments, linked to progress, or in the absence of progress, sanctions. However, when it comes to enlargement, applicant countries like Serbia will be reluctant to meet the demands that were not required of the Central and East European countries that acceded to the EU in 2004 and 2007, respectively. The EU adopted far more stringent conditionality, introducing them early on in the accession process than it had for the CEECs, making genuine compliance by domestic elites more difficult due to the issue of “double standards” and inconsistency of EU demands. Credibility also refers to the public engagements with Member States and aspiring candidates such as the Western Balkan applicants. Mixed voices in the EU regarding what constitutes the decline in media freedom and freedom of expression in general has led to a dissonance between public discourse and actual findings of the decline and limitations to media freedom in the EU Commission progress reports. While the EU Commission cites limited progress in the area of freedom of expression with the continuation of economic and political influence over the media outlets, this is not echoed in the EU’s public statements and actions toward Serbia. In her recent visit to Serbia, President of the EU Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, praised Aleksandar Vučić on Serbian progress toward accession, stating that, “it’s amazing to see the progress,” while simultaneously commenting that “it is essential to progress on the rule of law,” but “I know that you are working on it” (European Commission 2021b). This is in stark contrast to the EU progress reports that criticize and admonish Serbia for fake or even non-compliance evident in the lack of progress toward rule of law, especially freedom of expression. In 2015, the former EU Commissioner responsible for Enlargement Johannes Hahn made a statement that was not only admonished by the journalists’ associations in Serbia but also went against the very principle of human rights and democratic values, and thus enabled Serbian politicians to continue exercising their control over the media while compliance to EU conditionality had a “negligible effect” (Vogel Reference Vogel2015, 10). He claimed that he needed “evidence, and not only rumours” in response to concerns over the declining media environment in Serbia (BIRN 2015). Other statements have also contributed to the EU’s lack of credibility when it comes to enforcing domestic reforms in response to EU conditionality. In a report, the European Parliament claimed that

the EU does not have a specific policy devoted to media in the area of the Western Balkans. Media freedom, as conditional for EU membership, forms only a part of the EU’s enlargement strategy and, despite its importance for the democratic functioning of a country, is not necessarily the most central element of establishing compliance with EU norms. (European Parliament 2014b, 7)

Such a statement allows for Serbian elites to transpose EU conditionality on paper rather than efforts to genuinely reform the media sector in a way that would include the phasing out of government control and lead to norm internalization.

In addition to public engagements and statements by EU officials praising Serbia for efforts in other policy areas while ignoring rising concerns over the deterioration of the media, EU officials have offered rewards in the form of opening accession chapters, the latest being cluster 4 in December 2021, which is comprised of four chapters.Footnote 1

Conclusion

Democratic backsliding, including a decline in media freedom, is not a relatively recent or new trend, but historically it can be traced back to the legacies of communist rule in the former Yugoslavia. Moreover, media freedom was seriously curtailed during the 1980s when nationalists such as Slobodan Milošević came to power, under whom Aleksandar Vučić took on the role of information minister, sanctioning journalists and attacking media that were critical of the government. The political parties that had formed part of the Democratic Opposition that had brought about the downfall of the Milošević regime in 2000 lacked pre-communist legacies to fall back on and were much more concerned with political reform; thus, they failed to break away from their authoritarian predecessors (Kmezić Reference Kmezić, Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2018, 101).

While the EU retained a critical stance toward the declining media freedom standards in Serbia and its Balkan neighbors, it lacked both the competences and credible, clear conditionality that would have brought the media environment in line with European standards, thus enabling both media that were independent of political control and respect for media pluralism. Through its external incentives, the EU can either offer rewards to Serbia for compliance in the form of IPA and technical assistance, and the opening and closing of accession chapters, or it can withhold rewards and “punish” Serbia for lack of compliance, such as through the use of sanctions. Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier (Reference Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier2019) argue that “enlargement conditionality is dominated by ‘positive’ conditionality that seems to exclude the possibility of adequate responses in the case of a serious backlash against media freedom” (17). In Serbia, the praising of Serbian domestic elites by EU officials while overlooking abuses to media freedom has not led to a consistent conditionality policy and therefore genuine reform. This “positive” conditionality we have discussed in the paper has allowed for Serbian politicians to continue simulating domestic-compliant change to reap EU rewards in the form of funds and the opening of new accession chapters, while continuing to violate media freedoms. Mixed messages from the EU contribute to the overall absence of credibility, particularly in relation to what constitutes a free media.

The democratic backsliding and rise of illiberal democracies in the CEECS in the post-accession phase seems to suggest that the EU failed in its democracy promotion. However, we argue that despite the transition into illiberal democracies, the EU was successful in its external incentives approach in the Europeanization and democratization during the 2004 and 2007 enlargements of the post-communist bloc countries. With regard to Serbia and the Western Balkans, we argue that the EU has failed in this respect because mixed voices of EU officials, which sideline abuses in media freedom, have given Serbian elites the opportunity to simulate domestic-compliant change in a manner that would serve their own political interests rather than engage in genuine media reform.

Additionally, instead of having a consistent policy of sanctioning Serbian elites for fake or even non-compliance, the EU has often praised and chosen to reward Serbia for compliance in other policy areas, mainly that of its relations with Kosovo for the sake of regional stability, therefore contributing to the concept of “stabilitocracy.” Serbia ranks as the worst in the Reporters Without Borders Freedom of the Press Index (2022) than all the other Balkan applicants, 79th out of 180 countries (Bosnia: 67th, Kosovo: 61st, Montenegro: 63rd, North Macedonia: 57th) (Reporters Without Borders 2022). By comparison, the Member States and former Yugoslav republics rank at a higher standing: Croatia ranks 48 and Slovenia as 54.

Although Serbia’s ranking in the Reporters Without Borders Freedom of the Press Index had improved from its standing of 93rd to 79th, this does not suggest that media freedom has improved in the country (Reporters Without Borders 2022). Prior to the COVID-19 state of emergency, the Serbian government adopted a new media strategy for 2020–2025 in January 2020 along with an action plan for its implementation. However, findings by the European Commission 2021 report indicate “limited progress” when it comes to media freedom, with some journalists positing that reality on the ground is much worse than what can be gathered on this formulation of “limited progress.” Željko Bodrožić, President of the Independent Association of Journalists of Serbia, argues that

limited progress from the European Commission Report does not exist in practice. On the contrary, freedom of expression and equal terms for the work of the media are seriously undermined because the ruling Serbian Progressive Party directly or indirectly controls the majority of the media, turning them into its propaganda outlets. We are light years away from what the European Union considers to be proper media freedoms. (Švarm Reference Švarm2021)

The Action Plan stipulates that the media in Serbia should be free, journalists should be safe, the legal framework improved, and ownership transparent. While the document was drafted in a transparent way and identifies everything that is wrong, journalists, such as Bodrožić, worry that these are mere words on paper. Although Belgrade seems to have at least formally fulfilled the EU requirements through the adoption of a new media strategy and an action plan for its implementation, fake compliance remains to be the norm with no real efforts by the Serbian government to reform the media that would be in line with European standards.

Acknowledgements

For Oliver Ivanović (1953–2018), Serbian politician in Kosovo: May he see the work to which he dedicated himself finished.

Disclosures

None.

Appendix: List of Interviewees

Journalist A from the Independent Journalists’ Association of Vojvodina, Email interview, September 8, 2016.

Journalist A from the Independent Journalists’ Association of Vojvodina, Email communication, November 15, 2016.

Journalist B from the Journalists’ Association, of Serbia Zoom interview, October 14, 2022.

European Commission Official W, Face-to-face interview June 23, 2015.

European Commission Official X, Face-to-face interview, April 14, 2015.

European Commission Official X, Face-to-face interview, June 23, 2015.

European Commission Official X, Email interview, November 14, 2016.

European Commission Official Y, Face-to-face interview, April 14, 2015.