“Virilists and Jews are doing the land reform,” shouted a disappointed MP of the peasant party, Jan Dąbski, after an unexpected turnaround of the voting in the Polish parliament in July 1919 (Jan Dąbski, PSL Piast, 64:30).Footnote 1 He probably meant the MPs of the Club of Constitutional Work, some of them Jewish real estate moguls, who entered the Polish Sejm after recognizing their mandates from the pre-war imperial Austrian Parliament. “A peasant liberum veto,” the nationalists and conservatives replied in kind, when the peasant MPs refused to proceed with subsequent amendments to the land reform bill and left the room, singing an anti-aristocratic anthem, “Hail the Magnates.”Footnote 2 The land reform bill had already been disputed for a couple of days in the Sejm, and on each seating it whipped up emotions. It was finally accepted after a few more rounds of confrontations, but its form and later execution deeply disappointed both its supporters and beneficiaries.

In an Eastern European comparison, the Polish reform was, among contemporaries and modern scholars alike, widely considered moderate for its defenders or barely effective for its critics (Ludkiewicz Reference Ludkiewicz1929; Pronin Reference Pronin1949; Błąd Reference Błąd2020; Roszkowski Reference Roszkowski1995). They all agree, however, that it was far from radical. This is a surprising fact. At the outset of the Polish state re-created in 1918, the land reform set the agenda in most political programs. The manifesto of the first government of Poland urged peasants to accept democratic statehood if they “wish[ed] to be the master of their own land” (“Manifesto of the People’s Government of the Republic of Poland” 1918).Footnote 3 The significance of the problem was indeed grave. The vast majority of the population, 75 percent of all people in Poland, lived in rural areas, and over 65 percent earned their living from farming according to the 1921 census (Landau and Tomaszewski Reference Landau and Tomaszewski1957, 49). The countryside was suffering from poverty and land hunger resulting from overpopulation of peasant land, reaching from two to ten million people, depending on estimates. At the same time, less than 1 percent of landowners controlled almost half (47.3 percent) of the agricultural land. This 1 percent was manorial lands, sharply contrasting with more than two million unsustainable, small farms of up to five hectares, 60 percent of all farms (Błąd Reference Błąd2020, 100). The inhabitants of manors and peasant huts differed in all but the formal classification as farmers.

Against this poignant property concentration, the Polish land reform was very moderate and remains a theoretical outlier in a broader comparative light. According to Michel Albertus (Reference Albertus2015), in a global comparison, several factors enabled far-reaching reforms. A conflicted elite looks for support among the rural population or tries to outmaneuver its landed rivals and, hence, pushes the land reform. In turn, states can perform swift reforms only without looking back at various stop points, as bicameral parliaments or constitutional courts, which tend to protect private property and estate privileges (other comparisons with a more regional scope were presented by Roszkowski Reference Roszkowski1995; Jorgensen Reference Jorgensen2006; Richter Reference Richter2018). The Polish elites were conflicted and unsettled by war. The political conflict along ideological lines was intense and went across the old estates or class divisions. In a democratic, unicameral parliament, envoys of peasant constituencies confronted the waning power of the landed nobility, stripped of blazons and formal privileges. When the new state emerged on the wave of popular enthusiasm bordering revolution, its old elites were in disarray and grudgingly accepted wide-reaching democratization.

This is the time when interwar Poland was certainly the closest to introducing any more daring redistributive reforms (Próchnik Reference Próchnik1933; Porter-Szűcs Reference Porter-Szűcs2014). The landed elite hardly had any direct political representation and was politically isolated in the days of parliamentary surge, universal suffrage, and revolutionary shockwaves sent over Europe (Wojtas Reference Wojtas1983, 46; Próchnik Reference Próchnik1933). Meanwhile, the mass parties unified peasants, workers, and intelligentsia members, the latter often of gentry origin but already disenfranchised and often critical of the historical role of the nobility (Nałęcz Reference Nałęcz1994; Smoczyński and Zarycki Reference Smoczyński and Zarycki2017; Kurjanska Reference Kurjanska2019). Nonetheless, despite the unsettling war, raging rural poverty, land hunger, a seemingly wide consensus about the need to modernize rural areas, internal and external Bolshevik threat (another factor boosting land reforms in the region) (Alanen Reference Alanen, Granberg and Nikula1995; Jorgensen Reference Jorgensen2006; Suodenjoki Reference Suodenjoki2017; Richter Reference Richter2020), the swiping popular-democratic swerve, an initially unicameral parliament, and later autocratic rule (from 1926 onward), the Polish land reform remained minor.

The post war opportunity window defined future possibilities for all involved parties, sealing the divisions on the problem affecting directly two-thirds of the country’s population. Hence, it may be called a critical juncture, which could shift the scales and reconfigure the situation (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007). Decisions made in a relatively short time affected the situation for a long time and the opportunity window for daring moves closed soon afterward. Considering such a setup, it is a conundrum worth solving as to why the reform could not be executed effectively, despite a broad acceptance of its necessity across the political spectrum.

It has been argued that in Eastern Europe, the national question was a more important determinant of land reforms than strictly social or agronomic considerations (Richter Reference Richter2018). Correspondingly, to understand this debate, one must consider the ethnic composition of the country. Most postimperial states were characterized by ethnic diversity, but the relationship between ethnic groups was entangled with estate and class differentiation in various ways. Where landed elites were not the titular nation in the new state, a sort of ethnic reversal occurred, tumbling cultural hierarchies and privileges (Riga and Kennedy Reference Riga and Kennedy2009). This usually led to swift and uncompromising changes in land tenure aimed at unsettling the old, now foreign, elites and the creation of propertied national peasantry, as in the Baltic states (Richter Reference Richter2018; Jorgensen Reference Jorgensen2006). In other cases, though, the old elites remained the dominant national group in the new nation state and retained most of their land, as in post-Trianon Hungary (Eckstein Reference Eckstein1949). In Poland, the new national consolidation encompassed both scenarios.

Old elites of falling empires became obsolete former oppressors of the now dominant Polish nation (chiefly Germans, occasionally Russians, and other imperial elites), whereas in other places, these were the Polish nobles who were the guardians of the nation against encroachments of imperial governments and ethnically diversified peasantry. While the large proportion of urban industrialists were perceived as foreign, namely, German or Jewish (Zysiak Reference Zysiak2014), the land reform concerned the redistribution of land owned by the Polish noble class. Hence, it was relatively easier to negotiate limiting the powers of so-called “foreign elements” in the factories than to take land from the aristocratic elite and landed gentry who historically had been self-appointed torchbearers of Polishness. The land reform touched a sensitive nerve. While aiming at an expansion of Polish smallholdings in the former Prussian partition (at the expense of German landowners), many Polish politicians and pundits wanted to avoid parceling large Polish estates in the multiethnic Eastern regions.

In this way, nationalism underpinned the debate over redistribution. However, the literature on multiethnic legacies of empire in the nation state too rarely meets with structural social history and studies in social cleavages (Hein-Kircher and Kailitz Reference Hein-Kircher and Kailitz2018). The debate over land reform clearly shows that one set of problems could not be understood without the other and that the redistribution-heterogeneity nexus must be addressed. Despite some inconclusive evidence, there seems to be a historic link impeding powerful interclass transfers in conditions of ethnic diversity (Alesina and Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004). Beyond simpler entanglements (foreign vs. domestic elite; ethnically othered poor), in horizontally heterogenous states alternative cleavages weakened left-wing mobilization anyway (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2000). However, a mediating factor of multiculturalist policies may counteract this link, securing already existing redistributive institutions and perhaps fostering new schemes (Kymlicka and Banting Reference Kymlicka and Banting2006). Ways of defining “national political community” (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2001) have a significant influence on how heterogenous polities deal with redistribution. While Polish land reform was by no means to be a simple redistribution between ethnic groups, complex negotiations about national-political community are the crux of its conception, delivery, and stillbirth.

The new Poland emerged on the wave of pan-European democratization expressed in electoral reforms, parlamentarization, and land redistribution schemes (Mazower Reference Mazower2000; Fischer Reference Fischer2011; Ihalainen Reference Ihalainen2017). As it was a composite, patchwork state emerging on debris of three empires, the political scene was highly fractured, and national-political community and statewide cleavages were still largely in flux (Caramani Reference Caramani2004). Simultaneously, it was a strongly nationalizing state trying to unify its population and territory (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996) and an empire trying writ small to govern a heterogeneous population (Kumar Reference Kumar2010). The historical moment was marked by falling international acceptance for tiered citizenship and open discrimination (Fink Reference Fink, Boemeke, Feldman and Gläser1998). All these vectors met in the question of land tenure. Simultaneously, land reform was a nationing move and posed a danger to the national land holdings.

What makes nationalisms grounded, as Siniša Malešević (Reference Malešević2019) has recently argued, are national assumptions and imageries ingrained in a dense network of institutions. Taking this metaphor all too literally, I ask how nationalism was landed in the legislative process of state integration, aimed at creating landed citizens. While the main political parties shared tacit Polish nationalism, the history of earlier political alignments can shed light on underlying assumptions of its different breeds. Who was intended to be the carrier of the nation, and how the nation was envisioned in space, was to decide the fates of the land reform affecting a social and national jigsaw puzzle. To assess the ethnic underpinnings of the final form and execution of the land reform, one must first unpack the black box of the parliamentary process and look at its results.

Tipping the Scales of the Property Regime

The voting on the land reform bill interrupted by the peasant walkout is a good example of the meaning of sequence in political action (Slez and Martin Reference Slez and Martin2007). The support for particular provisions was determined by other, already accepted regulations (for instance, acceptance of expropriation was conditional upon the allowed limits of land holdings and financial compensations, to name only the simplest interdependency). Moreover, subsequent alternative proposals for amendments (such as those stipulating these limits) were voted one by one, meaning that every MP had to calculate carefully so as not to overbid. Once rejected, an amendment would not be back on the agenda again, and what remained was often unsatisfiable. However, to push through any idea in a highly fragmented parliament, one had to estimate forces carefully and gather support. This encompassed many lobbying and negotiations on private conventicles beyond the parliamentary forum or in the restaurant where MPs used to dine. This was the case as well this time, and one socialist politician was even accused on the parliamentary forum of consuming a too flamboyant chicken to speak in the name of the poor in the debate. Nonetheless, what mattered more was the sequence.

Most of the peasant MPs hoped for at least the compromise property limits free of parcellation, as proposed by a peasant politician Józefat Błyskosz and Stanisław Staszyński, then representing the National-Peoples Union, a political alliance of nationalist and conservatists (100–300 morgens as a limit free of parcellation, with some exemptions). This was still a viable backup option when, after days of debate, it became clear that the variant initially proposed by the land commission (60–300 morgens) would not gather enough support. Indeed, it was voted out by the skin of the teeth. However, the more compromising amendment gathered the same number of supporters as opponents, which meant that it was rejected too (Cimek Reference Cimek2006). This, practically, would bury the hope for substantial land reform in the peasant country with land hunger looming large. That is why the peasant representatives left the room, as they did not see another way out.

They had tried every formal trick to reassume the voting, but to no avail. The right, who held the position of the speaker, pushed to vote on further amendments. This would frame the peasant MPs to either accept the very moderate land reform or reject it straight away, taking political responsibility for its failure. The tense situation was mediated by socialist leader Ignacy Daszyński, the consumer of conspicuous chickens. He was aware that burying the vital longings of peasants under party quibbles and indefinite voting would be a heavy blow for the shaky legitimacy of parliamentarism in the peasant country. Thanks to his intervention, the voting was postponed, and after another day of formal quarrels, and even attempts to exchange the speaker of the Sejm, a tentative compromise was reached. The last standing amendment regarding these limits was sent again to the land commission (Komisja Rolna, the body which prepared the initial draft) to be redrafted in a way acceptable for the peasant parties.

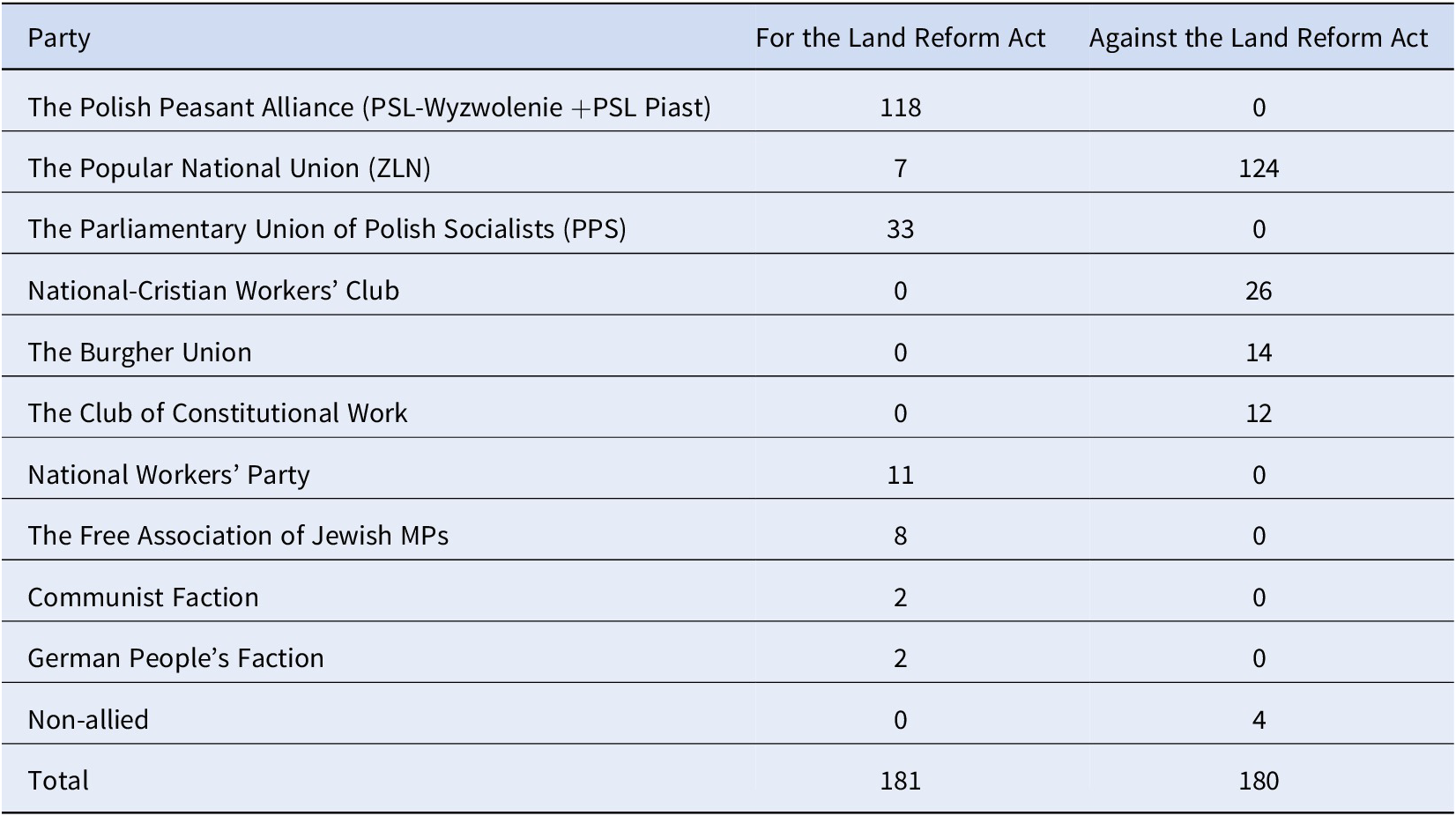

The commission redrafted the amendment, proposing two alternative wordings (and limits of holdings). The more daring, with a hybrid limit of 60–180 hectares, with exemptions for western and eastern lands, passed by a single-vote majority.Footnote 4 The peasant parties PSL Piast (Polskie Sronnictwo Ludowe – Polish People’s [Peasant] Party) and PSL Wyzwolenie, now forming an alliance, voted unanimously for the bill (giving 118 votes); the socialists chipped in with 33, while the rest were gathered among the National Workers Party, the Free Association of Jewish MPs, and some scattered members of ZLN (Związek Ludowo Narodowoy – Popular National Union), and other right-wing parties, mostly nationalist peasants keeping low profile in the Sejm and priests familiar with the rural reality (see table 1). However, the majority of the nationalists, and all conservatives, voted against the reform.Footnote 5

Table 1. Distribution of votes in the voting on the Land Reform Act of 10th of July 1919

Source: the name list of voting MP’s included in the stenographic transcripts of the Sejm Proceedings, session 67. Party affiliations verified with (Rzepecki Reference Rzepecki1920).

In addition, as the careful reader would notice, this tug of rope included changing the measurement unit stipulated by the bill from morgens to hectares. Hence, the same number expressing the bottom limit free from parcellation (i.e., weakening the impact of the reform) was actually bigger than initially debated. Many MPs may have been misled into accepting the bill.Footnote 6 Thanks to this stretch, the accepted reform was minor. Despite this stretch, the reform was sluggish. Therefore, it is worth asking how we can explain its relative weakness. Let us take a look at the debating parliament before this contested voting.

Poland, Its Minorities, and Its Parliament

The territory of the new Poland was still in the making among the “Central European civil war” (Böhler Reference Böhler2018) but in any possible form it would encompass ethnically diversified populations. Poland’s minorities were likely to exceed 30 percent of the total population. The figures in the 1921 census were as follows: Poles, 69.2 percent; Ukrainians, 14.3 percent; Jews, 7.8 percent; Belarusians and Germans, 3.9 percent each, with most of the Slavic minorities and a considerate proportion of Germans being rural populations (Horak Reference Horak1961, 81). All this was not a good platform for the harmonic coexistence of a diverse population now lumped together in one state, which Poles claimed to be their own. Not without reason, this diversity was not reflected in the legislative body.

The first Polish parliament (Sejm) after the creation of the independent state in November 1918 was active between February 1919 and November 1922. Its main duty was to create a constitution, and indeed one was finally accepted on March 17, 1921. The composition of the legislative Sejm changed as the borders of the country were not settled—when new territories were included, MPs were also added. While originally 296 MPs were elected in 1919, the ongoing cooptation of representatives of prewar imperial parliaments and various auxiliary elections made the composition as many as 432 MPs when the Sejm was dissolved. These machinations concerned chiefly ethnically mixed regions where elections were not conducted because of war and instability or were boycotted by local populations who opposed incorporation into Poland. What resulted was a virtual lack of representation of national minorities of the eastern lands, Belarusians, Lithuanians, and Ukrainians. This lack had grave consequences, going beyond a simple boost for the parliamentary position of the nationalist right.

Indeed, the nationalist political conglomerate, the National Democracy, with some conservative and Christian democratic allies acting under the umbrella name of Popular National Union (Związek Ludowo-Narodowy; hereafter, ZLN), capitalized on the peculiarities of the first elections. This ethnonationalist political alliance had already built numerous institutions in all three imperial states before the emergence of Poland on their debris. The idea of a national and nationalizing state appealed to a vast array of social groups, ranging from peasants to aristocrats. Firmly grounded in nationalist, middle-class, and landed gentry, the nationalists defended private property and a conservative idea of the state (Wapiński Reference Wapiński1980; on nationalist agitation among peasants, see Wolsza [Reference Wolsza1992]). While the peasant parties unanimously supported parliamentarism and claimed the commanding position in the state for the peasants (Cimek Reference Cimek2005), the most numerous social group, they differed in many aspects. The PSL Piast was more conservative and did not stand up against the church as the PSL Wyzwolenie did, which, in turn, was willing to cooperate with the socialists in the name of the popular classes. Christian democracy was not very strong and formed smaller parties catering to clerks and workers, which supported labor legislation but often sided with nationalists in other matters (Polonsky Reference Polonsky1972). All in all, the right held sway. At the beginning of the term, the nationalist camp (32 percent of seats) could easily count on the support of the right-wing peasant faction (PSL Piast) with 13 percent and smaller, center-right, conservative, or peasant formations summing up to another 20 percent (Ajnenkiel Reference Ajnenkiel1989, 28). Left-wing peasant parties and the socialists maintained a stable but limited foothold in the legislature, but they had little say in passing a standard bill, with 17 percent and 10 percent of seats, respectively.

It is easy to notice that peasant parties could not boast a clear majority in a peasant country, even if they principally agreed on the issues concerning land reform. The socialists supported the socialization of manorial land and not its redistribution to private owners, which effectively marginalized their position in this debate. The bulk of influence belonged to the nationalist ZLN, which practically decided the fate of the bills. Nonetheless, the extreme internal heterogeneity of this big-tent nationalist formation, the populist origins of some of its members, and the hairbreadth voting regarding the bill allowed the flickering moods of single MPs to tip the scales. Therefore, collective realignments following persuasive speeches or lobby consultations had a large impact (Ermakoff Reference Ermakoff2008). The fragmentation of the parliament paralleled the fragmentation of the state, and the major political forces had different visions of managing the diversity of the country.

The nationalists aimed at a hegemonic state putting into practice the idea of national assimilation. Non-Polish groups would be Polonized (Slavic minorities), marginalized (Jews), or encouraged to leave (Germans). The Slavic minorities of the eastern territories were considered a “passive tribal mass” (Maj Reference Maj, Jachymek and Paruch2001), not having decisive national properties. Hence, their national strives were reduced to haphazard outbursts and mere criminal activities to be eliminated. In contrast, long-cultivated anti-Germanism rendered Germans a severe danger, now whipped up by the presence of a vibrant residue minority. Jews were considered even more dangerous and foreign to Polish culture, and anti-Semitism became the main pillar of the national democratic political agenda (Bergmann Reference Bergmann2015). Not surprisingly, the idea of discriminating the minorities below the bar of the universal rights of citizens was openly discussed in nationalist circles. For instance, Roman Dmowski believed that the minorities should control no more than 25 percent of seats in the Polish parliament (Proceedings of the Polish National Committee in Paris, March 2, 1919, in Bierzanek and Kukułka Reference Bierzanek and Kukułka1965, 85–86). The idea was later put into practice with the help of the electoral law. “This system, strictly proportional and fully just [sic], is obviously unfavorable for dispersed minorities,” (Lutosławski Reference Lutosławski1922, 6.) commented one of its designers, nationalist priest Kazimierz Lutosławski, with unveiled satisfaction.

Among the peasant right, the possible influence of non-Polish elements in state politics triggered suspicion, too. Although supportive of universal suffrage, Wincenty Witos, leader of PSL Piast, himself of peasant stock, scolded the fact that “a Polesie villager living in forests and rushes” is entitled to decide “the fate of the Polish state” because “the legislators forgot about the difference” separating Polish people from “inhabitants of our land with lower national awareness” (Reference Witos1926, 4–5). The left-wing peasant movement was more supportive of the aspiration of minorities, yet it did not cross the line of questioning Polish territorial integrity.

Landing the Nation

On the surface, the land reform debate concerned the historical rights of people who had been deprived of land for generations. Indeed, the peasant populations might have had reasonable doubt about whether they had any stake in the new Polish state had it preserved land ownership. Peasants remembered the postfeudal realities of the second serfdom preserved well into the 19th century. They were aware that the three emperors had given them land unlike the Polish insurrections, which had failed partly because they did not address this issue in a sufficiently robust manner. The need to reform land ownership had haunted reformers in Poland ever since the noble estate republic finally collapsed in 1795—or even earlier, when necessary steps toward modernization were debated by the so-called Great Sejm (1788–1791) (Kizwalter Reference Kizwalter2014; Leszczyński Reference Leszczyński2020). Because land reform was perceived as “an unbroken thread” in the “history of Poland,” “since the struggle for independence begun,” there was a general agreement about the historical significance of the reform in the chiefly agrarian state and the right time to perform it (Jan Dąbski, PSL Piast, 44; see also Juliusz Poniatowski, PSL Wyzwolenie, 50; cf. Błąd Reference Błąd2020).

Such considerations were vital in the time of tormented state building and the challenge of the nominally pro-peasant Bolshevik regime looming large in the east. Members of Parliament were aware of the possible political volatility of the peasant population frustrated with land hunger. The proponents of the land reform floated a vision of a landed nation where citizenship was grounded in land ownership and “homeless popular masses which are susceptible to various Bolshevik agitations” “will feel grateful to the state, to the government, to the Sejm, and will feel organically bound to the state” (Jan Dąbski, PSL Piast, 44:33–34; see also Eugenusz Okoń, PSL Wyzwolenie, 157). Also, for Władysław Grabski, a national democratic politician supporting the reform, the reform would create “citizens of the country, even if they do not feel citizens yet—they are potential citizens and valuable material for the future” (Reference Grabski1919, 26). The final integration of rural populations into the state was a common coin in the Sejm and beyond.

These visions built upon the peasant attitude toward land. In the Polish case, there had barely been a living tradition of the land commune of the Russian type, and land had long been considered private property. In this way, the idea of the noble class nation entrenched in land property was generalized to encompass the peasant population. Now reaching beyond landed elites, the idea fulfilled the spatial, landed element existing in the Polish concept of citizenship (obywatelstwo), originating in the political imaginary of the political nation of the nobles (Janowski Reference Janowski and Bauerkämper2003). Correspondingly, the land reform was to be the means to bind the landed peasants to the new state. “Every farmhand, every proletarian, every pariah should feel that he has a stake in the existence of the state,” declared Jan Dąbski of PSL Piast (44:34), who initiated the land reform debate in June 1919. He connected land not only to the state as a political bond but also to the nation: “The land reform concerns land, the natural fundament of the nation – the territory, which is a condition of existence for the nation and statehood. […] The land reform that gives the land into the hands of a good owner is a great and effective state act, as it gives the land into the hands of those who will not give it away” (Jan Dąbski, PSL Piast, 44:33–34).

Other peasant politicians, too, saw “the rebirth of life” and the “creation of a powerful force within the nation” as dependent solely on land reform (Juliusz Poniatowski, PSL Wyzwolenie, 50:4). Such a project of the landed nation had its geopolitical outcomes. It chipped into the vision of greater Poland, which would make use of its capacities of an empire writ small—multiethnic composition, hybrid statehood, and universalizing ambition of a civilizing, bulwark nation: “Whoever does not want to do small, parochial [kramarskiej] politics but big international politics, whoever wants to turn Poland into a great power [wielkie mocarstwo] that will thrive between our two enemies, the Germans and the Muscovites, must build a strong bloc of states around Poland, united with one idea. Such a bloc could be built when the nations of the east are given a guarantee of Polish democracy [demokratyzmu]” (Jan Dąbski, PSL Piast, 44:53).

This was—rhetorically and quite literally in Polesie marshlands—a swampy ground. The elephant in the room was the fact that a large proportion of peasants, colonists, and land laborers were of an ethnically diversified background and either did not identify themselves as Polish or were excluded from the national community by other contemporary Poles. In the eastern lands, land redistribution would mean giving the land to Belarusians and Ukrainians, hence diminishing the Polish ownership. The possible impact of land reform on the national structure of land ownership was ushered in for the first time only indirectly, already as a preemptive counterargument. This testifies to the fact that the issue was considered possibly dangerous for the reform but also too important to ignore straight away. “It is about making […] citizens of our state out of these dissatisfied masses. It is about securing the interest of the state connected with land. Gentlemen, we have been debating the eastern borderlands many times […] and we bemoaned that the ethnographic holdings [stan posiadania etnograficzny] of Poland in the east is fragmented” (Jan Dąbski, PSL Piast, 44:33–34).

The key is to give the land “to firm and strong hands” which “won’t allow the land to be taken by any blow,” and the “millions of arms of the people” are contrasted with the “hands of the individuals” (i.e., the Polish noblemen on the borderland). “The land owned by peasants is safe for the nation” (Jan Dąbski, PSL Piast, 44:33–34), as the punchline goes, but it remained untold who these peasants would be.

Nationing the Land

Peasant parties certainly did not intend for the land reform to exclude the minorities. It was more the other way around; the idea was to keep the land for Poland and intensify the Polish influence to boost the political and national loyalties of the minorities. Among the left and the center, it was genuinely believed that Polishness could be an attractive and inclusive civilizational project if backed by an actual transfer of land titles. The rhetoric of the Polish civilizing mission in the east found its place here, just like in numerous associations grounded to spread Polishness and affiliated modernizing ideas deployed in the region (Ciancia Reference Ciancia2020). Against this backdrop, Błażej Stolarski of PSL Wyzwolenie took up the idea of “Polish holdings,” hitherto used in the debate to protect the holdings of the landed gentry. He did so, however, simply to accuse the nobility of the fact “that soil owned by the great landowners was in many places forever lost for Poland” and “fell prey to the international [sic] and its growth” (46:68). Witos argued, in a similar vein, “We do not want that [the foreign land grab] to be repeated. The people’s element gave evidence that it’s unperishable and could not be destroyed by enemies, and we want to settle Polish soil with this element and keep the land for Poland” (47:24).

However, more farsighted voices pointed out that the land reform was not only a key to the successful integration of the eastern lands to the state but also of their inhabitants to the nation: “Gentlemen, for God’s sake, go to Wilno, Lida, or Grodno. As a Belarusian, catholic, or orthodox, what is important for the people to join Poland, he will answer: land reform! […]. What you are doing is pushing the kresy in the Russian hands!” (64:2), as Dąbski attempted to appeal before the voting. He continued another day, “We won’t attract these peoples [without] broad liberties, new cultural values, integrating into Polishness those hitherto downtrodden” (44:53). The idea was to make Polishness an attractive political project and promote a possibly unified state. In the speeches in the parliament, the general vision of expanding the landed nation was, however, often conflated with arguments aimed against an alternative line of argumentation, also aiming at nationalization but of land without people.

Indeed, the question of Polonization of those lands was also the aim of the nationalist right. They had a different vision, however. Many, but not all, national democrats bent over backward to limit or at least delay the land reform. They did not want to use it for binding the local populations with Poland. Instead, the nationalists took the side of the landowners. They took eastern borderlands as empty land available for settlement and colonization, releasing the manorial lands in central and southern (ethnically Polish) Poland from claims of land-hungry peasants. “The land question would be easier solvable” when the “question of the eastern borderlands will be solved conveniently for us,” claimed one nationalist member of the land commission, himself a man of the Lithuanian borderland (Witold Staniszkis, ZLN, 45:44). The minister of agriculture, Stanisław Janicki (also associated with National Democracy), struck similar chords. The colonizing mission in the east correlated with the modernizing ambitions of the state and the goal of equalizing the population density, which was indeed lower in the eastern marshlands. However, Janicki did not beat around the bush and flagged “political factors,” that is, “national existence in the borderlands,” as an important consideration in the land reform: “Polishness stands firmly where a Polish peasant cultivates the Polish land,” so “the resettlement acting should be treated as an integral principle of the land reform” (45:31). Surplus Polish peasants should just go east.

For proponents of the reform, such arguments were nothing more than a thin veil hiding the sheer material interest of the landowners. If peasant politicians occasionally struck similar chords, this strategy was harshly criticized by the socialist MPs, who recognized the rights of ethnically diversified populations. In a skillful reversal, they cast the blame for agrarian underdevelopment on the noble class owners who now conveniently assumed the mantle of agrarian progress. While the “conservative” vision of the land reform “aimed at refocusing the attention of the people […] to the object of desire,” namely, “the Lithuanian and Belarusian lands,” they, as Norbert Barlicki argued, “must belong to the numerous local inhabitants who need the land there” (45:62). Arguably, Polish socialists were not free from patronizing attitudes toward the Slavic minorities of the eastern lands, but they definitely were the only political force able to admit them to the Polish polity as equals, instead of instrumentally trading with their interests (Jeliński Reference Jeliński1983; Michałowski Reference Michałowski, Jachymek and Paruch2001). All in all, the bulk of the debate concerned who would best serve the Polish territorial interest as the principal landowner: the peasantry, the landed elite, or the state.

Here, the core of the controversy over land reform reveals itself. In the Sejm, almost no national minorities were represented apart from those not prioritizing land ownership (the Jewish circle and a small, mostly urban, German group supported the project of the land commission). Among Polish parties, with the partial exception of the socialists, there was a shared consensus. It was the idea that the Polish land holdings guaranteed the territorial integrity and possible expansion of the state. What was common sense as well was the vision of modern, productive agriculture. However, the bone of contention was how these goals would be put into practice. Historian Katharyn Ciancia (Reference Ciancia2020) recently described competing visions of Polish civilization proselytized on the eastern borderlands. The old idea of a noble class manor as a torchbearer of Polishness clashed with a vision of modernization through colonization in the name of the nationalizing state and, in the parliament, with the prospects of attracting the minorities to Polishness with the land. All of them embodied the myth of a bulwark Polish nation with outposts facing the foreign environment, but they represented contrasting visions of this nation (Berezhnaya and Hein-Kircher Reference Berezhnaya and Hein-Kircher2019). While one preserved the idea of a manor house and nobility as a core of the nation withstanding russification and contamination by ethnic and estate otherness, the other coupled progressive postulates of land redistribution, population equalization, agricultural improvement, and the levelling up of the downtrodden mass. In some versions, this mass was only now to become Polish. It was Polonization of people through land instead of the Polonization of land through people.

Further Ethnicization of the Debate

The already heated debate over the land reform was unexpectedly punctuated by the urgent motion of the nationalist MPs regarding the Versailles negotiations. The 1919 Peace Conference created new states, but the impossible “One nation, one state” formula resulted in more than 25 million unassimilable minorities. Accordingly, the accompanying Minority Treaties, first with Poland and later with other states, sought to manage this situation, “a liberal minority rights regime that tried to create both ‘tolerant majorities’ and ‘loyal minorities’” (Riga and Kennedy Reference Riga and Kennedy2009, 461). The information that Poland was included in the group of new states and had to sign the so-called Minority Treaty created furious reactions, some of them suggesting an international (i.e., Jewish) conspiracy against Poland (Golczewski Reference Golczewski1981, 308; cf. Fink Reference Fink2006). A militant declaration expressing indignation against breaching the sovereignty of the Polish state was immediately accepted by the Sejm by unanimous acclamation. These lamentations notwithstanding, it was now clear that Polish legal order would need to be indifferent to ethnicity, and open discrimination was no longer advisable. The land reform was to be formally blind as well, not only concerning the eastern Slavic minorities but also with respect to the German colonists, who were widely perceived as heirs of Prussian colonization of Polish lands and, hence, legitimate targets of expropriation (Blanke Reference Blanke2014). The debate entered new registers.

The ethnic arguments reached their peak in the argumentation of the conservative landowners. Stanislaw Chaniewski, known for an unwillingness to beat around the bush, disclosed the national, colonizing ambitions and openly claimed that it was the private, large land ownership that would best serve the national interests. Not only were the landed elites torchbearers of Polishness, but they, in contrast to the impersonal state ruled by law, could remain openly discriminatory in managing the land. This curious idea begs for quoting at length:

Land expropriation according to the idea of the peasant parties will cut short the possibility to freely dispose the land of our former borderlands. […]. The state won’t be able to make an exception for a Pole, over the heads of a closer local, possibly having closer rights [sic]. In contrast, private property will have free choice. He [the private owner] can sell the land to whoever he pleases. […]. You can call it imperialism or nationalism, I do not care, but […] you cannot convince us that our peasant will be happy starving on a scrap of land only to allow some Hryćko or Gawryło [stereotypical Belarusian and Ukrainian peasant names] to take more land. (49:33)

The question of whether the benign landowners would indeed suppress the land hunger of “Hryćko or Gawryło” simply to welcome a Polish peasant from overpopulated central Poland must, for now, remain an unresolved mystery. What is clear is that Chaniewski revealed, in plain words, the crucial nexus of this debate. Not only did the rule of law badly serve the Polish land grab, but it was now additionally limited by the minority protection regime. Hence, even the redistribution of state land should be abandoned because one could not exclude the German colonists: “Almost two-fifths of peasants [in Western Poland] are Germans, and one cannot simply remove them now under the accusation of intolerance. If the article 91 of the Peace Congress demands far reaching guarantees for the minorities, then the Germans under the international care cannot be excluded from the colonization. […] We cannot dream to abruptly remove the Germans and exclude them from acquiring land on our western borderlands” (49:46).

What is more, the parcellation would encourage the Polish peasant to buy the land from the state and not from the suppressed German colonists. Hence, “the German element, which necessarily needs to be removed, […] would not be weakened but strengthened on the Polish lands.” All in all, any “parcellation would be a national defeat” (49:46). The shrinking possibility of legal discrimination seemed to stick in the craws of many MPs of aristocratic stock, accustomed to a tiered vision of citizenship, and more virulent nationalists alike, albeit for different reasons.

However, such an argumentation was a double-edged sword. Peasant MPs used the same arguments with an opposite vector, arguing that on the western lands “the issue of expropriation of land is a thoroughly national one” (Juliusz Poniatowski, PSL Wyzwolenie, 50:7; cf. Józef Kowalczuk, PSL Piast, 50). They argued that the majority of the larger property was owned by the Germans and, hence, should be expropriated along with the general and universal land reform, not violating the equality of citizens but nevertheless preventing the German landowners from voluntarily selling the land to German colonists. So, in a way, they applied the same private nationalism that Chaniewski used to protect the Polish land in the east against “Hryćko and Gawryło.” At the same time, Poniatowski warned against taking up the “shameful practices” of “German colonization in Poland” against the inhabitants of the eastern lands and hoped that “any evidence of disgrace against the Polish nation wouldn’t be gathered and such things wouldn’t be undertaken by the Polish government” (50:14). Whether that was, indeed, to be the case remained an open question.

The entanglement of the land reform debate and the controversy over minority protection reached its zenith in the metonymic conflation of the noble class owners who sold out Polish land and their political representatives selling Polish independence at the Versailles. Jan Smoła of PSL Wyzwolenie (as the reader already noticed, a heterogenous party) defended the sovereignty of the state, entitled to expropriate without international consultation, whatever the reason: “You, gentlemen of the right have already contributed to the fact that there in Paris again clauses are applied to the Polish state. You led us into various subjugations […] but we won’t give up on independence, and we will distribute the national good alone” (52:44). Admittedly, this statement was uttered against the clergy, who tried to limit the national sovereignty by asserting that the last instance for the redistribution of church lands is the Holy See.

Finally, the limits of parcellation were increased in the eastern lands. Although wrapped up in agronomic considerations of soil quality, an MP from the Burgher Union summed up the issue: it was not a secret that “these lands were inhabited by foreign peoples” and “parcellation on far eastern lands” would cause these lands to “fall in hands of unpolish peoples.” Hence, “now a larger norm for these owners” “who saved Polish national interest” would “save the land, the space, for the Polish national interest” (Józef Zmitrowicz, 64:8). In the final wording, however, any reference to colonization was wiped off. Interestingly, nobody else but the same socialist Barlicki who defended Lithuanian rights to the land suggested penning the bill accordingly: “In the project of the land commission there is a term ‘colonizing, colonist,’” he claimed. “But we have our own term, a very good one: farming and farmer” (61:47). The exact intentions of these whitewashing moves are not clear. It seems plausible that socialists, when facing the failure of their own ideas of ethnic integration via socialization of land, wanted to prevent the destructive performative impact of the bill on the prospects of this integration. Despite all these efforts, there was still a long way to go to execute the bill.

The War Mobilization and the Postwar Backlash

Nonetheless, even if the path from a bill to an act was short—according to the Small Constitution, legal acts were published after being signed by the prime minister and the responsible minister—the execution by the government could be postponed for a long time. What is more, the land reform required many supplementary acts to be put into practice. The devil was in the details, such as timing, compensation for the parceled land, and schemes of its redistribution. Months passed, and not much happened. As the reform loomed large, landholders scrambled to minimize its impact on them. Peasants could only look on as they sold their land to speculators or divided their holdings among family members to avoid parcellation. The situation with forests was even more alarming. Many owners simply cut down all their trees and sold them for timber, assuming that forests would be nationalized.

What whipped up proceedings in the Sejm was the war with Bolshevik Russia. Unlike in many other successor states of the Russian Empire, this conflict was not a civil war. Despite the Bolshevik attempts to kick-start a proxy communist regime, efforts to turn the war into an internal conflict on a mass scale went off half-cocked. Nonetheless, it was not simply a war of states, as the visions of social order that clashed were manifestly different. Bolsheviks tried to attract the landless with the promise of immediate land redistribution, and they indeed occasionally expropriated manorial lands on the seized areas (Davies Reference Davies1972; Lehnstaedt Reference Lehnstaedt2019; on landless farm laborers and the Bolsheviks, see Szczepański [2000]). Correspondingly, the stake of land reform was now much higher. The danger of introducing it from outside, over the heads of the Polish landed elite, just like in the Czarist reform of 1864, loomed large. This entanglement initially stimulated promises aimed at binding the peasants with the state. However, the low level of internal unrest minimized the pressure to deliver them.

When the Bolsheviks advanced, the idea was floated to form a coalition government that would unite the major political forces around the common task of universal mobilization to defend the country. Immediately, a controversy broke out over whether this should be a more popular peasant-worker government or, rather, a strong government of “national salvation.” All these were contested notions, and there was already a growing skepsis against the mere rhetoric of democratization of the ownership structure, as one of the speeches shows: “The national defense, gentlemen, that’s what is at stake. Defense of the nation’s independence. […] Defense of the peasant and worker masses in the military, but not with cheats and scythes upended in the newspaper newsrooms” (Ignacy Daszyński, PPS, 156:21–22). Peasant and socialist MPs were anxious about the instrumentalization of the patriotic fervor among the popular classes. Many realized that the failure to implement a land reform contributed to the frustration of the rural poor.

Now, landless masses on the battlefield were to decide the fate of war against the Bolsheviks, who were promising land redistribution. This time, the previously imagined Bolsheviks turned up in flesh and blood at the gates of Warsaw. To “save Poland in the present situation,” the “state has to be reconstructed to make workers and peasants feel at home” by the immediate “implementation of the land reform which can no longer remain on paper only” (157:22), appealed the radical priest Okoń. In early July, Witos made an urgent move regarding the bill on the state purchase of land to be distributed. The bill—repeating the previous agreements in a less radical form—was passed unanimously amidst war mobilization and patriotic fervor (Land Reform Act of July 15, 1920; see Ustawa z dnia 15 lipca 1920 roku o wykonaniu reformy rolnej 1920). Arguably, this was possible only because Bolsheviks were sieging Warsaw and had already begun to liquidate landed nobility as a class on the eastern borderlands. The bill included parcellation of state-owned land and church demesnes, as well as parcellation of private estates with partial compensation. The land was to be given with priority to landless peasants and agricultural laborers, and with second priority to smallholders. At the same time, those who had appropriated land spontaneously or avoided military service were deprived of the right to receive land.

Interestingly, again, the land reform coincided in time with the question of minorities. On the very same day, when the bill on compulsory selling of the land for redistribution was finally passed, a liquidation bill also went through (July 14, 1920; note that bills are announced with a later date than there are voted). It stipulated the compulsory selling of German-owned land to the Polish state (Ustawa z dnia 15 lipca 1920 r. O likwidacji majątków prywatnych w wykonaniu traktatu pokoju, podpisanego w Wersalu dnia 28 czerwca 1919 roku 1920). Under Articles 92 and 297 of the Versailles Treaty, Poland had the right to purchase, with reasonable compensation, any properties owned by German citizens. In addition, all postarmistice property transactions on the postwar Polish territory were declared futile, allegedly to avoid any property transfer once the German state realized the necessity of giving up these lands. This created serious troubles for many Germans with incomplete paperwork.

A coalition government was formed a few days later, and Witos became prime minister. These steps assured the popular classes about their political representation, and the Bolsheviks were defeated. While the peasants were often indifferent at the beginning of the conflict, later they more willingly supported the Polish forces, enthusiastically chasing the Bolsheviks once they were in retreat, and the promise of the land reform clearly contributed to this shift.Footnote 7 The land reform, however, got stuck as before, and the left wing suffered defeats regarding the constitution, finally accepted in March 1921. Not only was the parliament to be bicameral, introducing an important stop point hindering any further daring reforms, but private property was now entrenched in the constitution (Article 99), making any swift expropriation impossible. In May 1921, the land reform was back on the agenda, but this time it was an outright backlash. The constitutional protection of property was interpreted in a manner requiring full compensation for parceled land, initially being half of an average price. Once the state strengthened and the threat of radicalism and destabilization seemed to be gone, the right-wing MPs did not hesitate to undermine the legitimacy of previous decisions and bills. “The atmosphere in which the principles of the land reform were decided”—claimed one of them—was an atmosphere “marked by the westward spread of moods predicting the abolition of private property.” Thus, the bill on the implementation of the land reform had been “accepted unquestioned” because “the enemy had already encroached through the walls of our fortress” (Witold Staniszkis, ZLN, 314:29–33). Once the Bolshevization of the landless masses was no longer a threat, the balance of forces changed too.

The political loyalties of landless farm laborers were directly questioned. Indeed, occasionally they had greeted the Bolsheviks with enthusiasm and assisted in the expropriation of manor houses (Szczepański Reference Szczepański2000). The right wing politicians made hay while the sun shined: “The representatives of the Farm Laborers Union almost everywhere welcomed the Bolsheviks very kindly” (Jan Zamorski, ZLN, 173:22). It was now possible to argue that the landless population did not deserve land because it had proved to be disloyal. The accusation that manor servants, “under the influence of the Union,” had “helped the Bolsheviks and greeted the Polish military with dissatisfaction,” while those not affiliated with the Union had “behaved completely differently” (Karol Mierzejewski, ZLN, 201:27), was also deliberately used to undermine the position of unions.Footnote 8 These arguments had an ethnic undercurrent, too, as many of these land laborers were ethnically diversified according to the nationalist standards, many of them being, for instance, poor, rural Belarusians. Their political volatility was easy grist for the mill of accusations against the traitors of Polishness.

The Ethnicized Impact of the Reform

All in all, the results of the reform were far below expectations. The land parcellation was further diluted by a supplementary bill (Act of December 28, 1925, on Land Reform Implementation; see Ustawa z dnia 28 grudnia 1925 roku o wykonaniu reformy rolnej 1925). After the democratic swerve had faded away and old elites had regained resoluteness, the dust of the initial critical juncture settled, and the window of opportunity for more daring moves closed. The redistribution ebbed and flowed, barely exceeding parcellation of state land and voluntary reselling by private owners, who could themselves choose the areas to be sold out. Not surprisingly, many landowners were selling out the worse land for a full market price simply to acquire cash for investment or consumption. When these incentives vanished after the great crisis of 1929, the reform slowed down rapidly. By 1938, roughly 2,654,800 hectares of land had undergone redistribution into 734,100 parcels, acquired by 629,900 people (Błąd Reference Błąd2020, 104). Only 7 percent of arable land was parceled, including the expropriation of German property and distribution to veteran colonists. These figures made the reform the most insignificant of the interwar reforms in all of Eastern Europe (Roszkowski Reference Roszkowski1995, 129). Additionally, the state parceled all the land it acquired and much land it had already had. Thus, the reform was also a de facto privatization, unlike in other comparable cases, in which the state took an actively developmental role. While the reform was minor and theoretically ethnically blind, the minorities were indeed targeted.

The danger of “taking of land by foreign hands” and losing it for Poland “seriously worried the public,” which ended in the parliamentary question expressing anxiety about “wild parcellation of land, often going into Ruthenian hands” (parliamentary question of ks. Dr. Kazimierz Kotula, no. 1076, note that he previously voted for the reform, just as a form of securing the land for the nation). Correspondingly, there was much rhetorical framing of the reform as a reversal of earlier Prussian colonization on the western lands (Richter Reference Richter2020, 273). But the bulk of actual land Polonization was still executed by various, hand-tailored administrative measures and harassments. According to the liquidation act with the annulment law, the Polish administration liquidated about 200,000 hectares of privately owned German land in the early 1920s. Affected property owners often complained that Poland offered unfairly low prices as compensation (as low as 10 percent of the market value, additionally lowered by numerous Germans selling the land at the same time) and hesitated to pay them swiftly. In addition, Poland refused to recognize property rights to farms created by the Settlement Commission during and after the war. From 26,000 settlers whose property rights were challenged because of the faulty paperwork of the Prussian government or mortgage issues, about 4,000 decided to accept Polish citizenship (a condition for staying and retaining the land), but rights to about 60,000 hectares of land nonetheless remained questioned (Blanke Reference Blanke2014, 68–70). The farmers were forced to vacate the land in 1920. Their cases in the League of Nations blazed the path for many other German-Polish clashes which were to be considered by this body (Raitz von Frentz Reference Raitz von Frentz1999). This system was not effective, though, and did little to reverse the tide of new territorial arrangements and property redistribution along national lines.

In contrast, the eastern Slavic minorities were not actively encouraged to leave the country. They did not profit equally from the land reform, however. For instance, Ukrainian farmers received only 6 percent of the land redistributed in East Galicia (Giordano Reference Giordano2001). This is a strikingly low proportion concerning the fact that after all in Eastern lands the general figures for land parcellation were the highest (Horak Reference Horak and Völgyes1979, 138–143). Instead of parceling land from former Russian demesnes and other state property to the local peasants to bind them with the state, the solution adopted was to distribute it among war veterans turned into settlers Polonizing the land (Ciancia Reference Ciancia2020; Kuźma and Ohir Reference Kuźma and Ohir2020). This solution was possible only because of lacking parliamentary representation for the eastern lands, as the settlers were resented by local peasants and Polish nobility alike. A danger for both groups (as competitors for parceled land, taken partially from former estates, respectively), settlers themselves petitioned the state to include more local populations in the process to cool down the tension (Stobniak-Smogorzewska Reference Stobniak-Smogorzewska2003, 22, 46, 63). These attempts were a voice in the wilderness, but the colonization had unintended impact as well. As much as one-fourth of acquired land was sold to the local peasants by settlers trying to make ends meet (Kuźma and Ohir Reference Kuźma and Ohir2020). All in all, the veteran colonization ultimately backfired and only increased ethnic conflict in the region.

Not only did the Ukrainian and Belarusian peasants receive a small amount of parceled land, but some of their holdings were confiscated. Poland declared even smaller farms as abandoned if their owners had been displaced during the war (Richter Reference Richter, Balkelis and Davoliūtė2016). Countless farmers fell victim to war evacuations, targeting, in particular, populations deemed unreliable by the Czarist government, such as Volhynian Germans (Gatrell Reference Gatrell2005). After returning from exile, they often found their land and farmsteads occupied by others, and their tenure agreements were not respected.Footnote 9 German nationals and Ukrainian nationals were often expropriated because the requirement of continuous residence was, for them, unfulfillable due to war resettlements. It was levied only for those once deported because of their Polish origins, which obviously targeted the minorities indirectly (Richter Reference Richter2020, 282). Last but not least, according to the land reform act, the peasants had to buy out the parceled land, the state serving as a creditor only (Roszkowski Reference Roszkowski1995, 139). This introduced another ethnic filter, as acquiring a loan from the land bank required additional administrative literacy. The result was the significant emigration of peasantry from these lands, especially after the further deterioration in living conditions after the great crisis (Horak Reference Horak and Völgyes1979, 144). A possibly arbitral crediting decision was not always made in favor of Ukrainian or Belarussian peasants. As we have seen above, such an ethnicized impact of the reform was considered by the lawgivers. What entanglements decided that a broad national alliance, ready to support a universalistic reform ethnically skewed in practice anyway, could not be formed?

Taming the Reform: The Structure of Cleavages

The fact that the conservative political camp representing large landowners did not support far-reaching land reform is not surprising. They tried to veil their goals in the cloth of protecting the national interest, allegedly better served by private property, capable of bypassing any universalist state policies and openly discriminating against various ethnic groups. They were not, however, those who decided on the fates of the reform. Those who held sway in the parliament were the nationalists, still boasting a broad popular base in rural areas. They seemed to agree with the peasant parties on the necessity of reforming the agrarian economy, they shared the idea of the nationalizing state, and they wanted to assimilate the Slavic minorities; but they nevertheless clashed on the actual execution of the land reform. Their action in the parliament was so divergent that it led to a clinch described at the beginning of the article and effectively blocked further-reaching reforms.

Two visions of civilization were applied by Polish nationalists on the eastern lands now incorporated into the Polish state. The enlightened reformers wanted to patronize local peasants and ushered them into the modern democratic state under Polish tutelage. They clashed with the conservative representants of the Polish ex-nobility residing in manor houses, considered a stronghold of Polishness and European civilization. A similar controversy came to the fore in the Polish parliament. While almost all the political forces shared basic premises of Polish nationalism and aimed at the integration of the state territory under Polish leadership, they differed in the assessment of how to achieve such a goal and who could do it. The visions of the nationalizing state were strikingly different.

Peasant parties and most of the smaller center formations supported the vision of property-based peasant stability, possibly binding the ethnic others via land ownership. Despite their tacit national profile, peasant leaders (of both the right-wing Piast and the left-wing Wyzwolenie) were ready to distribute the land to all Polish citizens, regardless of their ethnicity. While they admitted that plots on the eastern lands would be given to Ukrainian or Belarusian populations, they accepted it as a means useful for integrating the territory and binding the local populations with the Polish state. They considered the noble class as a bygone formation which brought no prospects for the future of the Polish state. Similarly, they considered German landowners as rightfully expropriated, but they nurtured no obsession against well-integrated German farmers who accepted Polish citizenship and wanted to toil their plots.

In contrast, the political alliance built around National Democracy tended to see the landowners as legitimate heirs of the Polish national tradition and heroes of the long struggle for the Polishness of land. Hence, they were afraid that parcellation would weaken the “Polish” land holdings—in the east by distributing the land to peasants considered non-Polish and in the west by weakening the drive to buy out the German colonists. Some more daring nationalists were ready to admit that their ambition to Polonize the cities (i.e., push out Jews) would be compromised if Polish peasants got land, which would after all keep them in rural areas. Admittedly, this argument was voiced more prominently as a retrospective critique of the reform (Stojanowski Reference Stojanowski1937). Such a stance, especially the vision of a bulwark nation in the east, was not obvious for a party having its roots in a populist national project and openly opting for an ethnically homogenous, compact statehood with forcefully integrated Slavic minorities. In the National Democracy camp, there were also prominent voices in favor of strengthening the middle peasantry as a stronghold of the nation and an anti-revolutionary safety net (Wojtas Reference Wojtas1983, 66). As a socialist politician noted bitterly, “There are still signs of the old affect toward peasants; on the other side there are those who from 1905 on brought a new element of the landed elites” to National Democracy (Zygmunt Dreszer, 47:41).Footnote 10 The nationalist party indeed evolved from a populist movement to a modern catch-all party (Porter Reference Porter2000). Amidst this process, it began to attract landowners by promising stability and taming the revolutionary upsurge after 1905. Internal voices in the movement admitted this, too (Kozicki Reference Kozicki1964, 284–285; cf. Wapiński Reference Wapiński1989, 157). During the turbulent early years of independence this tendency intensified, and many estate owners looked favorably at the nationalist camp as capable of controlling the masses (unlike the elitist conservative politicians), effectively blocking the revolution again. Nonetheless, the stance of the party toward the land reform had deeper roots than catering only to the landed elites.

The nationalist attitude to the land reform can be explained by the history of the emerging party system and ideological cleavages organizing it. Miroslav Hroch once pointed at a varying relationship of the peasant movement to the national one across Eastern Europe. In some cases, agrarianism was “born from the core of national movement and as its specialized continuation, while in the Polish countryside it started in competition with national political parties, even though one of them, the national democrats, made the peasant myth into one of the basic pillars of their program” (Hroch Reference Hroch, Schultz and Harre2010, 87, 98; author’s translation). Hence, the bulk of the nationalist movement, controlling the largest party in the Polish Sejm, was not directly affiliated with the interest of the peasantry despite long-term, successful efforts to mobilize it for the national cause (Wolsza Reference Wolsza1992) and significant numbers of peasants in their ranks (12 peasants out of 74 MPs in the core ZLN, the proportion exactly paralleling the number of landowners, see Wojtas [1983, 72]). As a consequence, the nationalists were not ready to support more daring reforms, possibly encroaching on the interests of all the other groups they wanted to attract. The tent of the nationalist party was too big to be moved in the direction of a property-based nation of individual peasants, even if this would secure the land holdings of the Polish nation.

Such a cleavage can be analyzed against the backdrop of a broader political landscape in Poland and abroad (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). In a European comparison, the place of peasant movement in relationship to other ideological currents was crucial to determining the political trajectories of the state between dictatorship and democracy (Moore Reference Moore1966; Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991). Polish socialists, even leaving alone the increasingly marginal communist party, were too orthodox to unanimously support land ownership of individual peasants and, therefore, remained a relatively weak party of urban workers and radical intelligentsia.Footnote 11 The communist threat was real, but it remained merely external, despite the hysterical reactions of some of the right wing politicians. In fact, the internal social conflict was weak, so the push to give land to the peasants to prevent their radicalization withered away just as the war with the Russian Bolsheviks was won.Footnote 12 Similar peril pushed many nominally elitist and socially conservative regimes to execute more daring land reforms. In Finland, for example, after beating the socialist contenders in the civil war, the victorious right gave land to peasants to secure their support, arguably because a sort of peasantism remained in the core of the national project (Alanen Reference Alanen, Granberg and Nikula1995, 43). In contrast, in Poland, there was no need to bid for peasant voters who did not vote socialist anyway.

While precise data on the social background of voters is not available, looking at the regional voting patterns clearly confirms that in rural regions, especially in the ethnically mixed eastern lands, socialists did not score high. For instance, the Polish Socialist Party (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) gained over 20 percent of votes in Warsaw and 16.5 percent in provincial Lublin. Meanwhile, the party rarely crossed the 2 percent threshold in the eastern constituencies. A striking exception is the Belarusians-Polish area around Pinsk where the PPS crossed 40 percent in three constituencies.Footnote 13 The agrarian question was addressed in socialist programs, and there were even voices postulating a tighter alliance with peasants, inspired by successes of Nordic socialisms (Wojtas Reference Wojtas1983, 358). The PPS itself hardly tried to mobilize peasants besides publishing one, not particularly popular, periodical.Footnote 14 All in all, these efforts stopped at the bar of tactical alliance with the left of the peasant movement.

Although the PPS did not cater to peasants, a broader anti-leftist alliance supported by peasants fearing the socialization of land did not form in Poland, in contrast to the European-wide pattern. Poland did not enter the fascist path, common in cases in which such an alliance came to fruition (Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991). The left was too weak to be dangerous, and peasant land ownership too minor to be feared about. It remained so despite the intensifying drift to the right of the National Democracy after 1922 (Brykczynski Reference Brykczynski2016) and its growing, or returning, sympathy for peasants (Wojtas Reference Wojtas1983, 92). The PSL Piast courted the nationalist, hoping in vain for swifter land reform, but this marriage of convenience, even when holding formal power during the so-called second, and later third, Witos’s government in 1923 and 1926, was merely a stalemate.

It was the former socialist born of borderland nobility and supporter of the federative idea, Józef Piłsudski, who organized a preemptive coup d’état, derailing Poland from the parliamentary-democratic path in May 1926. The coup was initially backed by the secular intelligentsia and the socialist party fearing right-wing nationalism (Plach Reference Plach2006). This constitutes an interesting mirror image to the right-wing movements taking power by fanning antisocialist obsessions. The combination of inclusive nationalism and sensitivity to inequality, the bygone of Piłsudski’s hallmarks, was exactly the missing piece to overcome the nationalist opposition to the land reform.

Many have hoped for such a breakthrough, but it did not come to fruition. Piłsudski’s regime widely coopted the landed elites instead and cemented the new state elite along with the old property regime. Piłsudski intensely tried to alienate the state and landed elite from the nationalists and build support beyond the left (Garlicki Reference Garlicki and Coutouvidis1995). This shift was sealed by flamboyant aristocratic rallies in Nieśwież and Dzików, visited by Piłsudski or his close cooperators (Kasiarz Reference Kasiarz2020), and ministerial nominations of conservatives, reaching its zenith when a die-hard landed mogul of the eastern lands, Karol Niezabytowski, became the minister of agriculture (Próchnik Reference Próchnik1933, 256). The landed elite found an unexpected safe haven in Piłsudski’s political apparatus. Yet again, the marshal grasped the reigns on the back of the left, just to turn to the right afterward. In response, the nationalists, cut from their landed allies, drifted back to their populist origins, but now brushed with a fascist taint. This in turn made them more interested in pushing out Jewry from the cities than strengthening peasant households. All this buried the last hopes for any intensified land redistribution.

The miniscule Polish reform, being a global outlier from a bird’s eye view, appears to be a contradictory case after one zooms in. The parliamentary rhetoric, sequence of moves, and voting alignments show the entanglement of the land reform with the ethnic diversity in a postimperial, nationalizing state, or perhaps even a small empire disguised as a nation state. The reform was considered a stabilizing factor binding the population with the state, a factor which farsighted nationalists acknowledged. This assumption, historically accurate (Mazower Reference Mazower2000), mattered doubly in the age of revolutionary shockwaves over Europe and the ongoing war with the Bolsheviks. The reverse interpretation, seeing the reform as a Bolshevik idea itself, popped up only occasionally in internal quibbles and on the international forum (Richter Reference Richter2018). This did not suffice, however, to harness enough support for a daring reform.

In the current moment, national self-determination and minority protection were setting the tone for constitutional ideas travelling across borders. It became clear that the reform, at least officially, could not serve the ethnic Poles only. Therefore, it was perceived as ambiguous, if not dangerous, for Polish national aspirations in the east. Arguments presenting the local Polish gentry as fundaments of Polishness could gain traction despite the alternative vision of broadening the legitimacy of the state among minorities via land redistribution. While peasants remained land hungry, minorities were increasingly antagonized to the Polish state. Both problems were addressed after the World War II in the Stalinist land reforms and involuntary population resettlements, creating an ethnically homogenous land of landed peasants.

Disclosure

None.

Financial Support

My research was supported by the National Science Centre, Poland, research grant Opus 14, no. 2017/27/B/HS6/00098, realized at the Robert Zajonc Institute for Social Studies, University of Warsaw. The article was written during my fellowship at the Academy of Finland Centre of Excellence in the History of Experiences, University of Tampere.

Acknowledgments

I would like to warmly thank Claudia Eggart, Pertti Haapala, Ville Kivimäki, and Sami Suodenjoki for their useful comments on various drafts of this paper.