No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

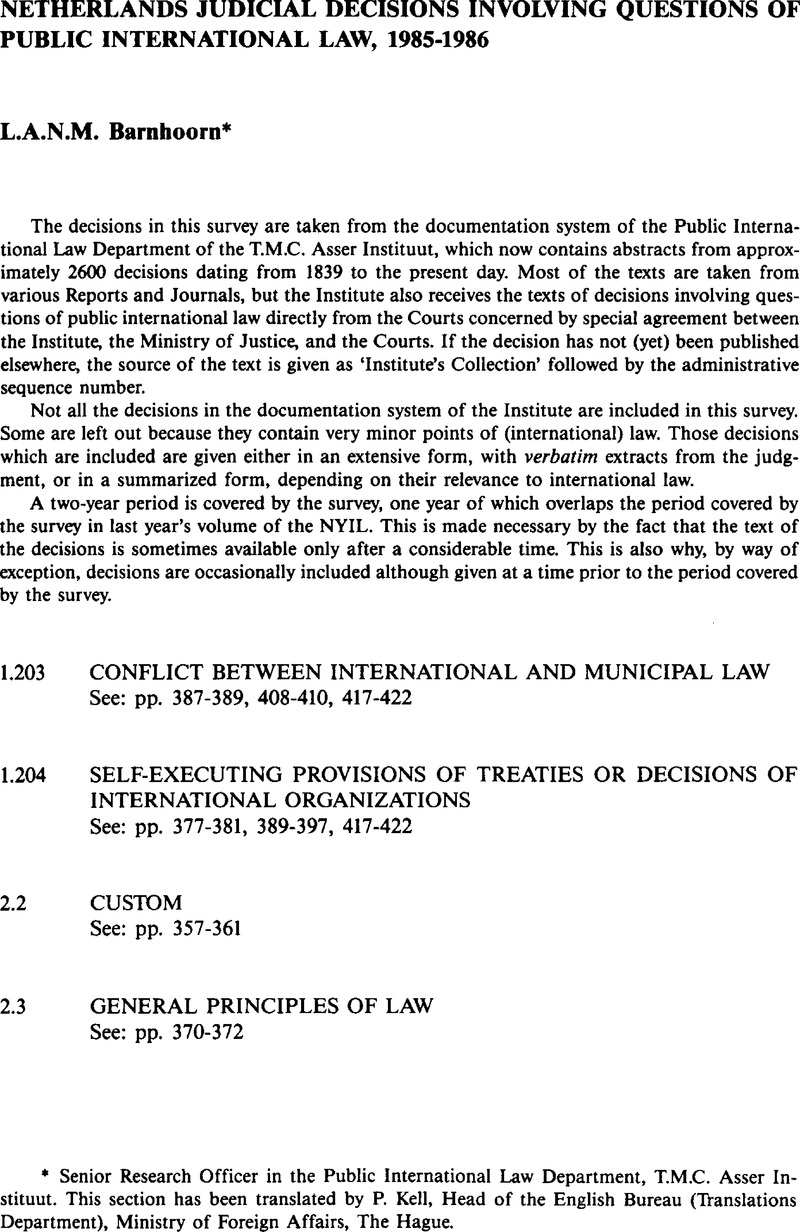

Netherlands judicial decisions involving questions of public international law, 1985–1986

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 July 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Documentation

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © T.M.C. Asser Press 1987

References

1. Institute's Collection No. 1892.

2. De Trappenberg had also brought proceedings against Morocco previously, in 1978, on the assumption that no recovery would be possible against B. It requested the Court for a garnishee order to secure the debt on funds held by Morocco in accounts at the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas. The Court complied, whereupon Morocco applied to the Court for an interlocutory injunction for the cancellation of the garnishee order. The President gave judgment for Morocco. (judgment of 18 May 1978, 10 NYIL (1979) pp. 444–445, ILR Vol. 65, p. 375).

3. Morocco relied, inter alia, on the order in council of 27 June 1967, Stb. 1967, No. 343, which provided among other things that diplomatic and consular representatives of a foreign power resident in the Netherlands and the civil servants assigned to them are not regarded as employees within the meaning of the Compulsory Health Insurance Act, provided that they are not of Dutch nationality.

4. NIPR (1985) No. 176.

5. B. had Moroccan nationality.

6. Partly reproduced in NIPR (1986) No. 222.

7. Stb. 1954 No. 596; NTIR (1958) p. 107.

8. Art. 158 (1) reads as follows: ‘In cases which have already been instituted before an ordinary court between the same persons on the same subject, or if the dispute is related to a case which has already been instituted before an ordinary court, a request may be made for the case to be referred to the other ordinary court …’

9. Art. 23 (1) reads as follows: ‘The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the Netherlands in respect of judicial matters in Surinam and in the Netherlands Antilles shall be regulated by Kingdom Statute …’ For an example of the application of Art. 23, see 17 NYIL (1986).

10. Note by de Waart, P.J.I.M., summarized in NJB (1986) p. 109 (No. 20).Google Scholar

11. 15 NYIL (1984) pp. 429–432.

12. 16 NYIL (1985) pp. 471–472.

13. 20 ILM (1981) p. 224; Trb. (1981) No. 155. Art. II reads: ‘(1) An International Arbitral Tribunal (the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal) is hereby established for the purpose of deciding claims of nationals of the United States against Iran and claims of nationals of Iran against the United States, and any counterclaim which arises out of the same contract, transaction or occurrence that constitutes the subject matter of that national's claim, if such claims and counterclaims are outstanding on the date of this agreement, whether or not filed with any court, and arise out of debts, contracts (including transactions which are the subject of letters of credit or bank guarantees), expropriations or other measures affecting property rights, excluding claims described in Paragraph 11 of the Declaration of the Government of Algeria of January 19, 1981, and claims arising out of the actions of the United States in response to the conduct described in such paragraph, and excluding claims arising under a binding contract between the parties specifically providing that any disputes thereunder shall be within the sole jurisdiction of the competent Iranian courts in response to the Majlis position.’

14. Art. VI (1) reads: ‘The seat of the Tribunal shall be The Hague, The Netherlands, or any other place agreed by Iran and the United States.’

15. This is the Act approving accession to the Convention concerning the privileges and immunities of the United Nations, as passed by the General Assembly of the United Nations on 13 February 1946. Art. 3 reads: ‘We reserve the right to ratify treaties and to take other measures in order to confer upon other international organisations privileges and immunities corresponding to those conferred upon the United Nations under article 1 of the said Treaty.’

16. Art. 125b reads: ‘The petitioning party may at his discretion file a petition at the registry of the Sub-District Court in whose area the employment is normally performed or in whose area the other party has his place of residence and may request the Sub-District Court in the said petition to set a date on which the case will be heard in court.’

17. Art. 13a reads: ‘The judicial jurisdiction of the courts and the execution of court decisions and of legal instruments drawn up by legally authorised officials (authentieke akte) are subject to the exceptions acknowledged under international law.’

18. Note by D. Bomans.

19. Note by R. Fernhout. Discussed by Andriessen, A. and Wolff, T. in ‘Het begrip “hoofd-verblijf” in de Vreemdelingenwet’ (The concept of ‘principal residence’ in the Aliens Act), NJB (1986) pp. 640–643Google Scholar with comment by M.G.W.M. Stienissen, Th. Holterman, Jaime Sau C and W. Fleuren on pp. 1283–1285 and the reply by Andriessen en Wolff on pp. 1285–1286 (the comments and reply are also published in Migrantenrecht (1987) pp. 25–28). Also discussed by Boeles, P. in AA (1985) Katern 16, p. 622.Google Scholar

19a. Note by R. Fernhout.

20. Art. 13(3) reads: ‘An alien who has had his principal residence in the Netherlands for a period of five years may be refused the permit only: (a) if there is no reasonable guarantee that he will have sufficient means of support in the long term, or (b) if he has committed a serious breach of the peace, a serious offence against public order or constitutes a serious threat to national security.’

21. Art. 9 reads: ‘An alien holding a residence permit shall be allowed to reside in the Netherlands until such time as the permit expires.’ Art. 10 reads: ‘1. An alien shall be allowed to reside in the Netherlands for an indefinite period of time if: (a) he holds a permanent residence permit; (b) he has been admitted by Our Minister as a refugee. 2. Aliens other than those referred to in paragraph 1 may be granted permission to reside in the Netherlands for an indefinite period by or pursuant to an order in council.’

22. Andriessen and Wolff, op.cit. n.19, submit that until the date of the present judgment the Judicial Division regarded principal residence as a question of fact. They base their submission, inter alia, on the judgment of the Judicial Division of the Council of State of 22 February 1979, Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1979) No. 62, Gids Vreemdelingenrecht No. D 17–9.

23. The Judicial Division reached the same conclusion in relation to Art. 13(4) Aliens Act in the judgment of 28 February 1986 in the case of S.S.A.A. el K. v. State Secretary for Justice (AROB tB/S (1986) No. 42 with note by H.P. Vonhögen).

24. Note by D.J.M.W. Paridaens.

25. Note by R. Fernhout, summarised in WRvS (1985) No. 2.190.

26. With note by W.L.J. Voogt.

27. Art. 14(1)(c) reads: ‘An alien's permanent residence permit may be withdrawn … if he has been sentenced under a final judgment for an offence intentionally committed, which is punishable by a term of imprisonment of three years or more.’

28. C. also used this submission before the District Court of The Hague, when he applied for an interlocutory injunction to prevent his expulsion from the Netherlands, until the Judicial Division of the Council of State made a decision on his appeal against the withdrawal of the permanent residence permit. The President of the Court disagreed with C'.s submission and dismissed the application (judgment of 8 May 1984, KG (1984) No. 156).

29. In its judgment of 29 April 1986, the Judicial Division came to the same conclusion in the case of H.D. v. the State Secretary for Justice, concerning the withdrawal of the permanent residence permit of D., a Turkish national, who had been sentenced in the Federal Republic of Germany to 4 years' imprisonment for trafficking in narcotic drugs (WRvS(1986) No. 2.118). On the same day the Judicial Division held that an application by D. in 1984 for a permanent residence permit could be refused under Article 11(5) of the Aliens Act on account of the same conviction in Germany (WRvS (1986) No. 2.117 Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1986) No. 42 with note by D.J.M.W. Paridaens). For earlier decisions on the same subject, cf., 7 NYIL (1976) pp. 308–310 and 10 NYIL (1979) pp. 459–460.

30. Note by W. Jansen, summarised in WRvS (1985) No. R.122.

31. See infra n.33.

32. 213 UNTS p.221; ETS No. 5; Trb. (1951) No. 154. Art. 8(1) reads: ‘Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.’

33. After his divorce on 9 May 1979, the residence permit granted to him on 7 October 1977 for residence with his (Dutch) wife was not extended. His application for review of this decision was dismissed, as was his subsequent appeal to the Judicial Division of the Council of State (judgment of 9 May 1983, partially reproduced in Rondzending van de Werkgroep Rechtsbijstand in Vreemdelingenzaken (1983) No. D-65). B. was expelled on 5 January 1984. He then lodged a complaint with the European Commission of Human Rights, contending that his expulsion was in breach of the rights contained in Articles 3 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. On 8 March 1985 the Commission held that B'.s complaint against the Netherlands was admissible (Application No. 10730/84, Rondzending van de Werkgroep Rechtsbijstand in Vreemdelingenzaken (1985) p.222Google Scholar, with note by Jansen, W., Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1985) No.107Google Scholar with note by Boeles, P., Tijdschrift voor Familie en Jeugdrecht (1986) p. 143Google Scholar, with note by J.E. Doek, discussed by Claassen, C. in ‘Het omgangsrecht van de vreemdeling’ (Parental right of access for aliens), Migrantenrecht (1986) pp. 37–39.Google Scholar

34. The appeal to the Judicial Division was withdrawn on 23 October 1985.

35. Art. 80 reads: ‘Pending appeal, a decision may, at the request of the interested person, be stayed, in whole or in part, on the ground that execution of the decision would result in harm disproportionate to the interest served by immediate execution of the decision. Provisional measures to prevent such harm are also possible at his request.’

36. In an application by L. to the District Court of Amsterdam for an interlocutory injunction to restrain the State from expelling him, pending the hearing of his application for a review of the decision to refuse him a residence permit, L. cited the decision of the Commission in the B. case. The application for the injunction was dismissed by the President of the District Court, who held that disregarding the fact that the declaration of admissibility by the Commission in no way meant that B'.s complaint would ultimately be held to be well-founded by the Commission or the Court of Human Rights, the arrangement for access by B. to his daughter differed so markedly from that in the case of L. and his daughter that there were no reasonable grounds for supposing that the Commission would hold in L'.s case too that there was ‘family life’ within the meaning of Art. 8(1). Yet even if it had to be assumed that every arrangement for access between parent and child after divorce constituted ‘family life’, it did not follow, in the opinion of the President, that continued residence in the Netherlands had to be permitted ipso facto in all cases. Since the contacts between parent and child were not very frequent in the present case (once every 14 days), it could not be said that the removal from the Netherlands of the alien/parent would be a disproportionate hardship constituting an interference within the meaning of Art. 8(2) (judgment of 5 December 1985, Migrantenrecht (1986) No.20, upheld by the Court of Appeal at Amsterdam on 3 April 1986, Migrantenrecht (1986) No.40, with note by Jaime Sau C.). With respect to the meaning of the declaration of admissibility by the Commission in the application of B. the Judicial Division of the Council of State concluded in the same way in the case of L.M. v. the State Secretary for Justice (judgment of 20 June 1986, Gids Vreemdelingenrecht No. D5–25).

37. B. remarried his ex-wife on 12 August 1985 and was granted a residence permit in September 1985.

38. Summarised in WRvS (1986) No. 2.86.

38a. Note by A.H.J. Swart.

39. 189 UNTS p. 137; Trb. (1951) No.131, amended by Protocol of 31 January 1967; 606 UNTS p.267; Trb. (1967) No.76.

40. Art. 1(F) reads: ‘The provisions of this Convention shall not apply to any person with respect to whom there are serious reasons for considering that: … he has committed a serious non-political crime outside the country of refuge prior to his admission to that country as a refugee’;

41. Art. 15(2) reads: ‘Admittance cannot be refused save for important reasons in the public interest, if refusal would force the alien immediately to return to a country as defined in para. 1.’

42. Art. 33 reads: ‘(1) No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. (2) The benefit of the present provision may not, however, be claimed by a refugee whom there are reasonable grounds for regarding as a danger to the security of the country in which he is, or who, having been convicted by a final judgement of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of that country.’

43. Art. 6 reads: ‘(1) In the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law.’

44. Art. 1(A) reads: ‘For the purposes of the present Convention the term “refugee” shall apply to any person who … (2) … owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.’

45. Art. 15(1) reads: ‘Aliens originating from a country where they have well-founded grounds to fear persecution for reasons of religion, political opinion or nationality … or membership of a particular group, may be admitted as refugees by Our Minister’. For Art. 15(2), see supra n.41.

46. In the case of F.S.E. v. the Minister for Welfare, Health and Cultural Affairs, the President of the Judicial Division similarly dismissed an appeal based on Articles 23 and 26 of the Convention since E. had not yet been recognised as a refugee (judgment of 25 June 1985, KG(1985) No. 282, Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1985) No. 87, with note by C. Groenendijk). Idem the Judicial Division in its judgment in the case of H.O. v. Burgomaster and Aldermen of Castricum relating to Art. 21 of the Convention (judgment of 20 December 1985, Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1985) No. 120, with note by C. Groenendijk).

47. Art. 11(5) reads: ‘The grant of a residence permit as well as extension of its validity may be refused on grounds derived from the public interest.’

48. T. was sentenced by judgment of the District Court of Amsterdam of 29 August 1980 to a term of imprisonment of one year, less the time spent in pre-trial detention, for an offence under the Opium Act.

49. Note by Swart, A.H.J., summarised in NJB (1985) p.816Google Scholar (No. 118) and DD (1985) No. 371.

50. Art. 3 reads: ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.’

51. 359 UNTS p.273; ETS No. 24; Trb. (1965) No. 9. Art. 9 reads: ‘Extradition shall not be granted if final judgment has been passed by the competent authorities of the requested Party upon the person claimed in respect of the offence or offences for which extradition is requested. Extradition may be refused if the competent authorities of the requested Party have decided either not to institute or to terminate proceedings in respect of the same offence or offences.’

52. Trb. (1971) No. 137; ETS No. 70.

53. Trb. (1979) No. 119; ETS. No. 86, Art. 2 reads: ‘Article 9 of the Convention shall be supplemented by the following text, the original Article 9 of the Convention becoming paragraph 1 and the under-mentioned provisions becoming paragraphs 2, 3 and 4: (2) The extradition of a person against whom a final judgment has been rendered in a third State, Contracting Party to the Convention, for the offence or offences in respect of which the claim was made, shall not be granted: a. if the afore-mentioned judgment resulted in his acquittal; …’

54. On 19 April 1985 Mc.C. was released after the West German authorities had withdrawn their extradition request. No reason was given for the withdrawal. In the case of K.G.W. v. the State Secretary for Justice, the Dutch Minister for Foreign Affairs stated that a request for the extradition of W., a German national, had been withdrawn by the German authorities because it has not proved possible to arrest W. in the Netherlands. The Minister made this statement at the hearing of the Judicial Division of the Council of State, which was hearing on appeal W'.s application to be admitted as a (de facto) refugee. The Division dismissed W'.s application. It considered that there was no well-founded fear of persecution because of political convictions, despite W'.s sentence to 13 months' imprisonment on 20 November 1978 by the Landgericht Hannover for criminal offences committed during the anti-atomic energy demonstration at Gröhnde on 17 March 1977 (judgment of 19 October 1984 (summarised in WRvS (1984) No. 2.134)).

55. Summarised in NJB (1986) p.168 (No. 1).

56. De Martens NRG, 2nd Series, Vol.33 p.41, Stb. 1898 No.113.

57. For Art. 6, see supra n. 43.

58. On 10 April 1984 the Netherlands sent an additional diplomatic note to the French Minister of Justice with a request that extradition should also be made possible, on the basis of reciprocity, for unlawful deprivation of liberty and extortion, which were offences that were not referred to in the 1895 Extradition Treaty between the Netherlands and France. This led H. to apply to the District Court of The Hague for an interlocutory injunction, claiming that the note should be retracted. The President dismissed the application. Cf., 17 NYIL (1986) pp. 267–269.

59. Judgment of 6 November 1985, RGDIP (1987) p. 981.

60. The plaintiffs summonsed the State to also appear before the full court of the District Court of The Hague mearly repeating their claims of the application for an interlocutory injunction. On 29 October 1986 the District Court dismissed the application on more or less the same grounds as the President (NJ (1987) No. 597).

61. This Article defines tort.

62. Cf., 9 NYIL (1978) pp.337–348.

63. Cf., supra n. 54.

64. On 6 December 1985 France decided to deport them to a country which did not have an extradition treaty with the Netherlands. Pending their extradition, they were accommodated in a hotel to the north of Paris. On 13 February 1986 they were transferred to the French part of St. Martin in the Caribbean. After protests by the local population, they were sent back to Paris, where they arrived on 20 February 1986. After the European Convention on Extradition entered into effect for France on 11 May 1986 (cf., DD (1986) pp.848–849), the Netherlands submitted a fresh request for extradition. On the basis of this request, the plaintiffs were then rearrested. On 9 July the Paris extradition court ruled that extradition was admissible for unlawful deprivation of liberty and extortion but not for threats to life, because extradition [for this offence] had already been declared admissible in 1985, after which the Dutch Government had withdrawn the related request for extradition. On 30 October the French Government served the orders permitting extradition. The following day they were transported to the Netherlands. The District Court of Amsterdam deemed them guilty of unlawful deprivation of liberty and extortion and sentenced them to eleven years imprisonment, less the time spent in pre-trial detention including that in France following the first Dutch extradition request as well as the second request. In relation to the length of sentence the Court took into account the fact that it was not possible to consider the time spent in France after the withdrawal of the first Dutch extradition request in ‘assignation à residence’ (6 December 1985 - 19 May 1986) as ‘pre-trial detention’ and the fact that the Public Prosecutor dropped the offence of threats to life, because extradition was not declared admissible by France for this offence (judgment of 19 February 1987).

65. Summarised in DD (1986) No.299.

66. Art. 12 reads: ‘(1) The request shall be in writing and shall be communicated through the diplomatic channel. Other means of communication may be arranged by direct agreement between two or more Parties’.

67. On 14 May 1985, the last day of the Pope's visit to the Netherlands, A. was taken from a train at Venlo and found to be in possession of a pistol and falsified travel documents. He was sentenced by the District Court of Roermond to 3 months' imprisonment for these offences. He was not released at the end of his sentence since Turkey had by this time applied for his extradition.

68. In the case of M.D. v. Public Prosecutor, the Supreme Court held that the District Court had wrongly declared that the extradition of D., a Yugoslav national, was admissible to the Justizbehörde of the Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg instead of to the Federal Republic of Germany. Although Article 6(a) of the Agreement between the Netherlands and Germany concerning additions to and the implementation of the European Convention on Extradition allowed for the possibility of correspondence between the Ministers of the States of the Federal Republic of Germany and the Dutch Minister of Justice, this did not alter the fact that extradition was possible only to the Federal Republic of Germany as contracting party as referred to in Article 1 of the European Convention on Extradition (judgment of 23 April 1985, NJ (1985) No.777. Summarised in DD (1985) No.377, NJB (1985) p.817 (No.119) and ELD (1986) p.271).

69. The Minister of Justice ruled at the beginning of May 1986 that A. could not be extradited to Turkey, because the Turkish authorities would not provide the Netherlands with a guarantee that he would not receive the death penalty in Turkey. He therefore remained in prison as an undesirable alien. As it was not expected that he could be expelled from the Netherlands, he was released at the end of October 1986. On 7 April 1986 the State-Secretary for Justice ruled for the same reasons that S. could not be extradited to Turkey (Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1986 No. 98 with note by D.J.M.W. Paridaens), although the Supreme Court declared his extradition admissible (17 NYIL (1986) p. 282 n. 90).

70. Summarised in DD (1985) No.363 and NJB (1985) p.816 (No.117).

71. Art. 539a reads: ‘(1) The powers conferred under any statutory provision in respect of the investigation of criminal offences outside a Court of law, may, unless otherwise provided for in this Title, be exercised outside the Court's jurisdiction. (2) … (3) The powers conferred under the provisions of this Title can be exercised only subject to international law and inter-regional law.’

72. Art. 4 of the European Convention on mutual assistance in criminal matters of 1959 (472 UNTS p.185; Trb. (1965) No. 10) and Art. 5 of the Agreement concluded between the Netherlands and Germany in 1979 on supplementing and facilitating the application of the European Convention on mutual assistance in criminal matters (Trb. (1979) No.143).

73. Note by G. Caarls (RV), summarised in NJB (1986) p.54 (No.12).

74. Art. 21 reads: ‘An alien may be declared undesirable by Our Minister: (a) if he has repeatedly committed an offence under this Act; (b) if he has been sentenced under a final judgment for an offence intentionally committed, which is punishable by a term of imprisonment of three years or more; (c) if he constitutes a threat to public peace, public order or national security and is not permitted to reside in the Netherlands by virtue of any of the provisions of Articles 9 or 10; (d) by virtue of that which is provided by or pursuant to an international agreement as referred to in Article 60 of the Constitution.’

75. 374 UNTS p.3; Trb. (1960) No. 40.

76. Trb. (1978) No. 171.

77. KG (1983) No. 280, Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenwet (1983) No. 49, with note by C.A. Groenendijk, summarised in NJB (1983) p. 1059 No. 17 and in Rondzending van de Werkgroep Rechtsbijstand in Vreemdelingenzaken (1983) No. D-76.

78. Institute's Collection No. 2371.

79. Art. 15 reads: ‘Aliens who are classified as undesirable in one of the Benelux countries may be expelled across an external frontier unless another Benelux country has an obligation to take over the alien or another Benelux country has given express consent to admit such aliens to its territory.’ Art. 16 reads: ‘Each of the Benelux countries shall grant consent for transit through its territory of aliens who are the subject of an expulsion order in another Benelux country and who may be expelled to third countries, if this is the quickest and simplest method of expulsion. The expenses incurred in connection with the transit shall be borne by the country which made the expulsion order. If the takeover by the foreign frontier control authorities does not take place for any reason, the alien shall be taken back by the last-mentioned Benelux country. If under agreements concluded with neighbouring third countries aliens are handed over by the foreign authorities to the authorities of one of the Benelux countries and the said aliens are in fact intended for another of the Benelux countries, the former Benelux country shall likewise grant consent for the transit of the alien through its territory at the expense of the country of destination.’

80. The Court of Appeal held that the correctness of its standpoint was borne out by the fact the Decision was not included in the summary of the common rules of law of the Benelux countries whose interpretation is entrusted to the Benelux Court. The contracting parties had therefore not wished to treat the Decision as one of the common rules of law which help to determine the relationship between the government and the individual in the States concerned. In its judgment in the case of A.H. v. the State of the Netherlands, the Court of Appeal of The Hague likewise denied that the relevant provisions should have direct effect (see infra n. 163).

81. All that could be established was that H. was born at Beirut in 1960.

82. Note by W.L.J. Voogt; summarised in WRvS (1985) No. 2.116.

83. 189 UNTS p. 137, Trb. (1951) No. 131, amended by Protocol of 31 January 1967, 606 UNTS p.267, Trb. (1967) No.76. Art. 33 reads: ‘(1) No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion’.

84. Cf., 14 NYIL (1983) pp.391–394.

85. Note by A. Possel.

86. Art. 429 quater reads: ‘(1) Any person who, in the exercise of his profession or the conduct of his business distinguishes between (onderscheid maakt tussen) persons on account of their race shall be liable to a term of detention (hechtenis) not exceeding one month, or a fine not exceeding ten thousand guilders.(2) … Cf., 13 NYIL (1982) p. 308’.

87. 660 UNTS p.195; Trb. (1966) No. 237.

88. Cf., 16 NYIL (1985) p.497 n.100.

89. Cf., 16 NYIL (1985) p.498 n.101.

90. Cf., 16 NYIL (1985) p.500 n.103. Fläkt appealed in cassation against the judgment but later withdrew the appeal.

91. Cf., 7 NYIL (1976) pp.330–331 and 8 NYIL (1977) pp.272–273.

92. Cf., 16 NYIL (1985) pp. 497–500.

93. The Court of Appeal took the following evidence into account in addition to the two letters: ‘… 4. A press release dated 7 March 1975 of the Embassy of Saudi Arabia at The Hague containing, inter alia, the following passages: …4. The Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia in The Hague would like to explain to the friendly Dutch people the whole truth behind the news published, on 8 March 1975, in “Vrij Nederland” under the title “Saudi Arabia refuses granting an Entry-visa: Jewish journalists may not accompany van der Stoel … It is regrettable that the writer of the news in question did not mention the whole story when he referred to his telephone call with the Consul of Saudi Arabia as the objectivity and honesty of quotation would necessitate; because the Consul made it clear to him in reply to his question over the reasons for banning Jews from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia that along history Saudi Arabia had nothing against Jews as being such. Nevertheless the last 27 years experience has always proved that Jews wherever they are do deeply stick to double loyalty, loyalty for Israel and loyalty for the State to which they belong and since the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is basically opposed to the principle of double loyalty and also was opposed to the creation of the Jewish racial State then it is only but natural that Jews are banned from Saudi Arabia on this basis. (…)5. The generally known fact, evident among other things from repeated statements on the subject in the media, that Saudi Arabia and in particular its Embassy still held the view expressed at 4. above regarding the non-admittance of Jews at the time when the charges were brought …’

94. Note by J. de Boer.

95. Note by J.A.O. Eskes, summarised in WRvS (1986) No. 3.108, discussed by D. de Wolff and F. Pennings in NJB (1986) pp. 498–499.

96. Art. G3(3) provides that the Central Polling Office shall refuse an application if: (a) there are reasons connected with public order or morals.

97. Applications Nos. 8348 and 8406/78, Decisions and Reports (1980) p. 187Google Scholar, NJ (1980) No. 525, with a note by A.E. Alkema.

98. 14 NYIL (1983) pp. 403–406.

99. Art. 8: ‘(1) Appeal lies to the Judicial Division of the Council of State if: … (a) the decision is in conflict with a provision binding on anyone …’

100. Note by J.P. Scheltens.

101. Notes by C.P.M. Cleiren and G. Oosterhof (p.64) and by P. Wattel (p.222).

102. Discussed by van Wieringen, J. in Delikt en Delinkwent (1986) pp. 790–798Google Scholar and (1987) pp. 389–394, summarised in NJB (1985) p.915 (No. 23).

103. Stb. 1966 No.332. Art. 16(1)(a) reads: ‘If a motor vehicle is driven on a public road without tax having been paid beforehand, the tax may be demanded subsequently in accordance with Chapter IV of the General State Taxes Act, provided always that: (a) the tax levied in the demand shall be increased by 50 percent, with a minimum of Df1. 25 and a maximum of Df1. 500, subject to analagous application of Art. 25, paragraph 5 of that Act’.

104. For Art. 6(1), see supra n. 43.

105. Art. 18(1) increases the reassessment and Art. 21(1) the ex post facto assessment by 100%, except in cases where the fact that too little tax has been levied is not attributable to intent or gross negligence.

106. Both Articles provide that if charges are dropped or the person concerned is acquitted or convicted by final judicial decision in respect of Art. 68, the surcharge ceases to have effect. The lapsing of the right to bring proceedings under Art. 76 of the Act is treated as the equivalent of a final conviction.

107. Note by P.A. Stein, summarised in NJB (1986) p.758 (No.120), discussed by J. Leijten in NJB (1986) p.815.

108. Note by A. Jacobs.

109. 359 UNTS p.89; Trb. (1982) No. 3. Art. 6(4) reads: ‘With a view to ensuring the effective exercise of the right to bargain collectively, the Contracting Parties undertake to recognize: (1) … (4) the right of workers and employers to collective action in cases of conflicts of interest, including the right to strike, subject to obligations that might arise out of collective agreements previously entered into’.

110. Art. 93 reads: ‘Provisions of treaties and of resolutions by international institutions, which may be binding on all persons by virtue of their contents shall become binding after they have been published’.

111. Art. 25 reads: ‘(1) The Committee of Experts shall consist of not more than seven members appointed by the Committee of Ministers from a list of independent experts of the highest integrity and of recognised competence in international social questions, nominated by the Contracting Parties’.

112. Art. 31 reads: ‘(1) The rights and principles set forth in Part I when effectively realised, and their effective exercise as provided for in Part II, shall not be subject to any restrictions or limitations not specified in those Parts, except such as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others or for the protection of public interest, national security, public health, or morals. (2) The restrictions permitted under this Charter to the rights and obligations set forth herein shall not be applied for any purpose other than that for which they have been prescribed’.

113. AB (1983) No. 560, with note by F.H. van den Burg. KG (1983) No. 333.

114. NJ (1985) No. 758.

115. This was the case, however, in the State of the Netherlands v. Algemene Christelijke Politiebond (General Christian Police Union) and Nederlandse Politiebond (Dutch Police Union). The President of the District Court of Utrecht therefore held that Art. 6(4) was not applicable to collective action taken by the police. Since various of the individual instances of action were incompatible with the legal protection to which subjects of the law are entitled and which the police are bound to provide, they were unlawful since they were in breach, inter alia of Art. 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights (judgment of 8 November 1983, AB (1983) No. 561, with note by F.H. van den Burg; upheld by Amsterdam Court of Appeal on 28 March 1985, NJ (1985) No. 759). As regards the application of the reservation, cf., also Supreme Court, 6 December 1983, 16 NYIL (1985) pp.526–528.

116. The text of the gloss reads: ‘It is understood that each Contracting Party may, insofar as it is concerned, regulate the exercise of the right to strike by law, provided that any further restriction that this might place on the right can be justified under the terms of Article 31’. Trb. (1962) No. 3, p.42.

117. In the judgment referred to above in n. 114, the Supreme Court left undecided whether Art. 6(4) could be regarded as a provision which may be binding on all persons by virtue of its contents.

118. Convention concerning freedom of association and protection of the right to organize, 9 July 1948, 68 UNTS p.18; Stb. 1948 No. J 538.

119. Art. 138 reads: ‘(1) Anyone who unlawfully enters a house, or the enclosed area or premises occupied by another person, … is liable to a term of imprisonment not exceeding six months or a fine not exceeding Df1. 600 … (3) The penalties determined in para. 1 may be increased by a third, if two or more persons commit the offence in conjunction’.

120. The Procurator-General demanded a prison sentence of eight weeks, five weeks of which would be suspended for a period of two years. The District Court of The Hague sentenced S., an Iranian national, in absentia to five months' imprisonment, 137 days of which were suspended for a period of two years and less the time spent in pre-trial detention (14 days), for occupying the Iranian Embassy in The Hague on 26 April 1984 and depriving the ambassador, the staff and other persons present in the Embassy of their freedom and destroying property (judgment of 17 September 1984, cf., Ch. Rousseau in RGDIP (1984) p. 955). As regards the occupation of the same embassy by 19 Iranians on 27 September 1984 and the unlawful detention of the ambassador and a number of embassy staff, the District Court of The Hague imposed a prison sentence of 4 months, 87 days of which were suspended for a period of two years and less the time spent in pre-trial detention (27 days). The Court therefore ordered the immediate release of the defendants (judgment of 30 October 1984, Institute's Collection No. 2397).

121. Summarised in NJB (1985) p. 1356 (No. 206).

122. 616 UNTS p. 79; Trb. (1972) No. 97. Art. 21: ‘(1) Transit through the territory of one of the Contracting Parties shall be granted on submission of a request by the means mentioned in Article 11, paragraph 1, provided that the offence concerned is not considered by the Party requested to grant transit to be an offence of a political character and that the person concerned is not a national of the country requested to grant transit’.

123. 6 Yearbook of the European Convention on Human Rights (1963) p. 14Google Scholar; Trb. (1964) No. 15. For the text of Art. 3 see under Held.

124. 16 NYIL (1985) pp. 509–513. A map of the Baerle-Duc enclave is printed on p. 511.

125. Institute's Collection No. 2304.

126. Application No. 10819/84.

127. The criminal proceedings before the District Court of Amsterdam were instituted on 31 May 1985 by means of the issue of a summons.

128. The Belgian Court of Cassation reached the same conclusion in its judgment of 17 January 1984, in which K's appeal against his provisional arrest was dismissed (Rechtskundig Weekblad (1984–1985) pp. 1147–1148Google Scholar, summarised in ELD (1985) pp. 374 and 375).

129. Note by H. Meyers, summarised in NJB (1986) p. 291 No. 44.

130. 516 UNTS p. 205; Trb. (1959) No. 123. Art. 15 reads: ‘(1) The coastal State must not hamper innocent passage through the territorial sea. (2) The coastal State is required to give appropriate publicity to any dangers to navigation, of which it has knowledge, within its territorial sea’.

131. Art. 14 reads: ‘(1) Subject to the provisions of these articles, ships of all States, whether coastal or not, shall enjoy the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea. (2) Passage means navigation through the territorial sea for the purpose either of traversing that sea without entering internal waters, or of proceeding to internal waters, or of making for the high seas from internal waters. (3) Passage includes stopping and anchoring, but only in so far as the same are incidental to ordinary navigation or are rendered necessary by force majeure or by distress. (4) Passage is innocent so long as it is not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal State. Such passage shall take place in conformity with these articles and with other rules of international law. (5) Passage of foreign fishing vessels shall not be considered innocent if they do not observe such laws and regulations as the coastal State may make and publish in order to prevent these vessels from fishing in the territorial sea. (6) Submarines are required to navigate on the surface and to show their flag’.

132. Arts. 14 to 17 fall within sub-section A: ‘Rules applicable to all ships’ of Section III ‘Right of innocent passage’ of the Convention.

133. S & S (1981) No. 104.

134. At the moment in question the ship was sailing in the Wielingen, a navigable channel the status of which under international law is a matter of dispute between the Netherlands and Belgium, cf., the map on p. 404 Cf., also Bouchez, L.J., ‘The Netherlands and the Law of International Rivers’, in International Law in the Netherlands, Vol. I (1978) p. 248Google Scholar et seq, ibid., The Regime of Bays in International Law (1964) pp. 130–135Google Scholar, Roos, D., ‘Grenzen van de territoriale zee en de Wielingen kwestie’ (Boundaries of the territorial sea and the Wielingen case), De Nederlandse Loods (1985) pp. 16–29Google Scholar, ibid., ‘Zeeuws territoriaal water en de Wielingenkwestie’ (The territorial waters of the province of Zeeland and the Wielingen issue), Zeeuws Tijdschrift (1985) No. 4, pp. 124–132Google Scholar. The 1979 situation on the map has, inter alia, been changed by the extention of the Dutch outer territorial sea limit from 3 to 12 miles in 1985 (17 NYIL (1986) pp. 244–245). In Belgium a similar Act is in preparation.

135. This is a reference to the consideration referred to under The Facts.

136. The Supreme Court used the Dutch translation of the text of the Convention.

137. Reported under WRvS (1985) No. V. 53.

138. Stb. 1975 No. 352; 7 NYIL (1976) p. 372. Art. 4: ‘It is prohibited to discharge or take aboard a vessel or aircraft with the aim of discharging, or deliver with the aim of discharging any waste or pollutant or noxious substances other than those covered by Art. 3(1) unless exemption is granted.’

139. The appellants also applied to the President of the Administrative Disputes Division of the Council of State for suspension of the exemption in accordance with Article 60a of the Council of State Act. This in turn led Kronos Titan to apply to the President to extend the former exemption of 7 April 1982 until such time as he had given judgment on the application for suspension. In a judgment of 23 December 1983 the President dismissed the application of Kronos Titan (WRvS (1984) No. G.5). Subsequently, on 30 May 1984, he dismissed the appellants' application for suspension because the objections had been declared unfounded in a Royal Decree of 25 February 1983, there was no evidence from official reports since then that there had been significant changes in the discharge area and the Crown would rule on the appeals in the short term. However, since allowing a further increase in the quantity of vanadium and chrome would not contribute to a gradual reduction in the pollution caused by the discharges (which was the aim of Art. 1 of the EC Directive of 20 February 1978), he granted the provisional measure ordering that for a period of one year the maximum amounts of vanadium and chrome which could be discharged were 187.5 tonnes and 75 tonnes respectively (WRvS (1984) No. G. 44).

140. 78/176; OJ (1978) L 54/19. Art. 1(1) reads: ‘The aim of this Directive is the prevention and progressive reduction, with a view to its elimination, of pollution caused by waste from the titanium dioxide industry’.

141. 11 ILM (1972) p. 262; Trb. (1972) No. 62.

142. On the same day, the Crown gave a similar ruling on the appeal of the appellants against the exemption granted to Pigment Chemie of Homburg (Federal Republic of Germany) for the discharge of the same kind of waste (WRvS (1985) No. V. 53). The legal developments preceding this appeal corresponded to those in the Kronos Titan case, see n. 139 above (Cf., also Milieu en Recht (1985) p. 178). For judgments relating to exemptions in respect of the discharges of Pigment Chemie cf., 15 NYIL (1984) p. 469 n. 157.

143. Article 2.01 (1) reads: ‘The master of every vessel shall be obliged when entering or leaving the port area to make use of the eastern approach to the port area, as indicated. Entering or leaving the port area in any way other than via the eastern approach is prohibited at all times’. Article 2.10 (1) reads: ‘Small vessels. It is prohibited to enter the port area or to be in the port area with a vessel which is propelled exclusively by one or more sails and with vessels with a water displacement of less than 15 cu.m., other than a tugboat.’

144. De Martens NRG Vol. 20 p. 355; Trb. (1955) No. 161, Art. 1 reads: ‘The navigation of the Rhine and its estuaries from Basle to the open sea either down or up stream shall be free to the vessels of all nations for the transport of merchandise and persons on the condition of conforming to the provisions contained in this convention and to the measures prescribed for the maintenance of general safety. Apart from these regulations no obstacle of any kind shall be offered to free navigation. The Lek and the Waal are considered as being part of the Rhine’. This text is taken from an unofficial English translation published in Cmnd. 2421.

145. The Scaldis had a water displacement of less than 15 cu.m.

146. See map on p. 409.

147. Cf., HR 9 March 1936, AD (1935–1939) No. 55 (in note). This has not evidently been altered by the fact that a barrier dam now closes off access to the open sea.

148. The District Court held that the provisions were necessary because of the danger which could arise if a disaster were to occur in the relevant area, since this might have serious or extremely serious consequences owing to the nature of the substances carried in the area and the loads being handled, i.e., oil products (Shell Nederland Chemie).

149. As regards the institution of the National Ombudsman, cf., ten Berge, J.B.J.M. in ‘The National Ombudsman in the Netherlands’, 32 NILR (1985) pp. 204–224CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Kirchheiner, H.H., ‘The National Ombudsman in a Democratic Perspective’, 32 NILR (1985) pp. 183–203.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

150. At the request of the National Ombudsman, the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs provided him with the following information on this point: ‘… In particular, there is no evidence whatsoever of a NATO rule to the effect that in the event of dual nationality member States are required to accord full recognition to military service performed in an allied country. The NATO States have expressly left the power to call up persons with dual nationality for military service to the individual Governments … Nevertheless, what does exist is the Convention of Strasbourg of 6 March 1963 on reduction of cases of multiple nationality and military obligations in cases of multiple nationality; however, neither the Netherlands nor Greece is a party to this Convention … This means that the Greek authorities are under no obligation whatsoever to recognise military service performed in another NATO country’. The Netherlands acceded to this Convention on 9 May 1985. The Convention entered into effect for the Netherlands on 10 June 1985: Trb. (1985) No. 75. The text of the Convention is published in Trb. (1964) No. 4, 634 UNTS p. 221, ETS No. 43.

151. The Minister for Foreign Affairs put it as follows: ‘… Because there is no treaty provision between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and Greece, it is necessary for the Dutch Embassy to proceed with caution in a case of desertion by a Dutch national who is also a national of the country of settlement, because there is great likelihood that intervention by the Government of the country where the person has settled will be construed as interference in internal affairs and may be counter-productive. I would point out here that the Kingdom of the Netherlands, unlike various other European countries, does intervene on behalf of a national with the authorities of the countries whose nationality the relevant Dutch national also possesses …’

152. Discussed by Swart, A.H.J. in note in Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1984) No. 115Google Scholar and by Zwart, J. in Onrechtmatige eigenwijsheid (Unlawful conceitedness) NCJM-Bulletin (1985) pp. 65–71.Google Scholar

153. Trb. (1982) No. 188; Trb. (1985) No. 68 (Dutch translation), Art. 36 reads: ‘The Commission, or where it is not in session, the President may indicate to the parties any interim measure the adoption of which seems desirable in the interest of the parties or the proper conduct of the proceedings before it’.

154. For the text see under Held.

155. Aanh. Hand. II 1977/78, 1581.

156. Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 27 June 1980, 28 European Yearbook (1980) pp. 313–314.Google Scholar

157. Art. 42 reads: ‘(1) The Commission shall consider the report of the rapporteur and may declare at once that the application is inadmissible or to be struck off its list. (2) Alternatively, the Commission may: … (b) give notice of the application to the High Contracting Party against which it is brought and invite that Party to present written observations to the Commission on the application. Any observations so obtained shall be communicated to the applicant for any written observations which he may wish to present in reply …’

158. The Court of Appeal of The Hague on 7 September 1984 upheld the judgment of the President of the District Court of Rotterdam.

159. Cf., van Dijk, P. and van Hoof, G.J., Theory and Practice of the European Convention on Human Rights (1984) pp. 57–58Google Scholar. For the reactions of States to a request by the Commission under Art. 36 or to the submission of a complaint to the Commission, cf., 17 NYIL (1986) p. 281 n.89 and 16 NYIL (1985) p. 513 n. 134.

160. Art. 38 reads as follows: ‘(1) Pending the decision of the Judicial Division on the appeal, the alien against whom the contested decision has been made, shall not be expelled. (2) Derogation from the provision in the first paragraph is possible: (a) in cases where the request for review has been decided in accordance with the opinion of the Commission; (b) in cases where, should the decision on the appeal be awaited, there would be no opportunity for expulsion in the foreseeable future’.

161. The Court of Appeal of The Hague upheld the judgment of the President of the District Court of The Hague. Unlike the President of the District Court, the Court of Appeal was also required to consider the question whether the request of the Commission under Art. 36 meant that the State was no longer at liberty to expel S. from the Netherlands. Like the President of the District Court of Rotterdam, the Court of Appeal held that this was not the case. The State did after all have a certain discretion as to whether or not to accede to such a request (judgment of 14 June 1984, Institute's Collection No. 2374). However, the Supreme Court quashed this judgment. The Court of Appeal had concluded as regards the application of the criterion for suspension (cf., NYIL (1985) pp. 492–496 and (1986) pp. 270–271) that the State Secretary's assessment of the situation was reasonable. The Supreme Court held that this conclusion did not preclude the possibility that the court which assessed the facts might itself arrive at a different decision from the State Secretary on the question whether reasonable people could doubt whether the alien was a refugee. The Supreme Court referred the case to the Court of Appeal at Amsterdam in order to answer the question on the basis of the correct criterion (judgment of 23 May 1986, RvdW (1986) No. 112, summarized in NJB (1986) p. 755 No. 112, NJ (1987) No. 188

162. Art. 3 reads: ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’.

163. Since the Commission had failed to make a request in accordance with Art. 36 after the submission of a complaint, The Hague Court of Appeal took this in the case of A.H. v. The State of the Netherlands as an indication that the complaint had little chance of success (judgment of 26 October 1984, in the case A.H. v. The State of the Netherlands, Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1984) No. 115, with note by A.H.J. Swart) or that the alien need not fear inhuman treatment after he had been extradited (The Hague Court of Appeal, 20 October 1983, in the case of S.S.D. v. The State of the Netherlands, Rechtspraak Vreemdelingenrecht (1983) No. 109, with note by A.H.J. Swart).

164. Summarised in NJB (1986) p. 732.

165. Note by P.W.C. Akkermans. discussed by Kuyper, P.J. and Wellens, K.C. in ‘Deployment of Cruise Missiles in Europe: the legal battles in the Netherlands, the Federal Republic of Germany and Belgium’Google Scholar, supra pp. 145–227.

166. Art. 90 reads: ‘The Government shall promote the development of the international legal order.’

167. Trb. (1985) No. 145.

168. 8 ILM (1969) p. 679; Trb. (1972) No. 51.

169. Art. 94 reads: ‘Statutory regulations in force within the Kingdom shall not be applicable if such application is in conflict with provisions of treaties that are binding on all persons or of resolutions by international institutions’.

170. The Dutch translation of the NATO decision and the Dutch declaration are given in Bijl. Hand. II 1979/80 - 15.887 No. 7.

171. Bijl. Hand. II 1983/84 - 18.169 No. 38.

172. In November 1983 a number of people from the peace movements formed what was called an ‘initiative’ group and instructed two lawyers, A.H.J, van den Biesen and P. Ingelse, to study whether legal steps could be taken against the State to prevent stationing. In April 1984 the initiative group set up the Foundation for the Prohibition of Cruise Missiles. The Foundation gave instructions to prepare proceedings and announced publicly that anyone could be included as a co-plaintiff in the proceedings after transferring Df1. 35 to cover the costs of the proceedings. In the end this invitation was taken up by 19,248 persons. After they had been divided into two groups, all of them acted with the Foundation as plaintiffs in the proceedings. This is why the District Court refers below to two sets of proceedings.

173. The writ of summons was published in full in 1985 by Ars Aequi at Nijmegen under the title ‘De dagvaarding’ (The writ of summons) and numbered 126 pages. An English translation was also published there. Cf., also Rabus, W.G., ‘Enkele volkenrechtelijke kanttekeningen bij de dagvaarding van de Stichting Verbiedt de Kruisraketten tegen de Staat der Nederlanden’ (Some international law remarks on the writ of summons of the Foundation for the Prohibition of Cruise Missiles), 60 NJB (1985) pp. 701–706Google Scholar, Willems, J.C.M., ‘Het proces tegen de Staat: Internationaal recht versus kruisraketten’ (The proceedings against the State: international law versus cruise missiles), 60 NJB (1985) pp. 707–713Google Scholar, Willems, J.C.M., ‘Het proces tegen de Staat inzake de plaatsing van kruisraketten’ (The proceedings against the State: international law versus cruise missiles), Rechtshulp (1985) No. 12 pp. 3–10Google Scholar (comment by H. van Son and reply by Willems, J.C.M. in Rechtshulp (1986) No. 2Google Scholar), Dekker, I.F. and Schrijver, N.J., Ars Aequi (1986) Katern No. 16, pp. 642–643, No. 17 pp. 699–700.Google Scholar

174. The Foundation has appealed against the judgment to the Court of Appeal of The Hague.

175. De Martens NRG, 3rd series, Vol. III p. 486; Stb. 1910 No. 73; Trb. (1966) No. 281.

176. 94 LNTS p. 65; Stb. 1930 No. 422.

177. 75 UNTS; Trb. (1951) Nos. 72–75.

178. 78 UNTS p. 277; Trb. (1969) No. 32.

179. 16 ILM (1977) pp. 1391–1449; Trb. (1978) Nos. 41–42.

180. 7 ILM (1968) p. 811; Trb. (1968) No. 126.

181. 213 UNTS p. 221; Trb. (1951) No. 154.

182. 6 ILM (1967) p. 368; Trb. (1969) No. 99.

183. Cf., also the literature referred to at 14.127 in 16 NYIL (1985) pp. 570–571. Cf., also 16 NYIL (1985) pp. 320–332.

184. Bijl. Hand. II 1985/86–17.980 No. 24.

185. On 5 November 1985 another Foundation, namely the Stichting Miljoenen zijn Tegen (the Millions are Against Foundation), applied for an interim injunction in an attempt to stop the parliamentary approval of the agreement. It requested the President of the District Court of The Hague to order the State to investigate whether the contents of the agreement on the stationing of 48 cruise missiles on Dutch territory, which had by then been signed but not yet ratified by Parliament, were not in breach of international law. The President dismissed the application, holding that it required the court to interfere in the process by which a convention is concluded. Under the Dutch constitutional system, however, the power to conclude treaties was reserved to the King and the States General. The courts could not interfere. He then held that the premise that such an investigation had not yet taken place was incorrect. It was reasonable to assume that the State had instituted an investigation on many previous occasions into the question whether the threat to use nuclear weapons and a possible use thereof itself was permissible under international law. The State gave eight examples of cases in the period 1949 to 1985. The fact that the Foundation did not agree with the conclusions of the investigations was an insufficient reason for ordering a further investigation. (KG (1985) No. 376, AB (1986) No. 41).

186. Cf., also supra pp. 551–552, Dekker, I.F. and Schrijver, N.J. in Ars Aequi (1986)Google ScholarKatern 17 p. 700, Katern 18 pp. 750–751, Katern 19 p. 784 and Kooijmans, P.H. in ‘Karakter en looptijd van het verdrag over kruisvluchtwapens: politiek in een juridisch jasje’ (Character and validity of the Agreement on cruise missiles; politics with a legal mantle), Internationale Spectator (1986) pp. 47–52Google Scholar.