Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

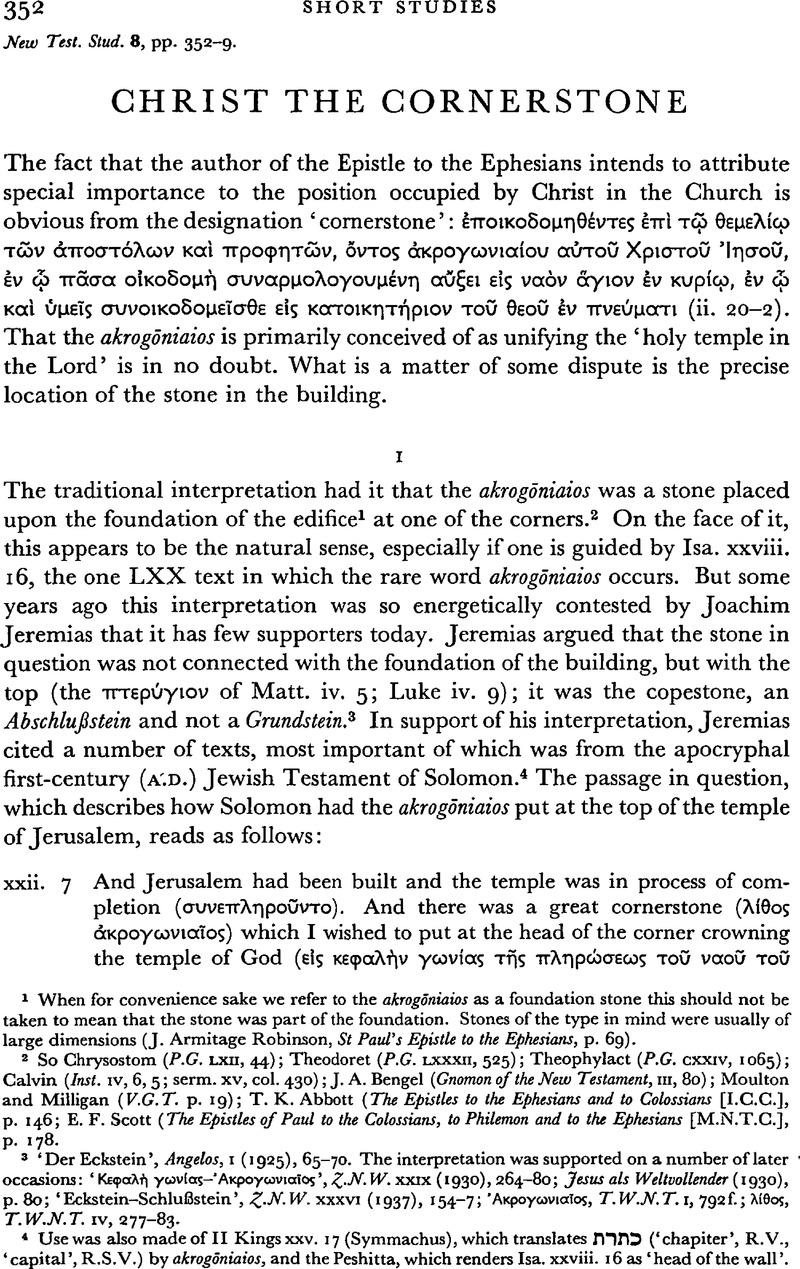

2 So Chrysostom, Google Scholar (P.G. LXII, 44;Google Scholar) Theodoret (P.G. LXXXII, 525); Theophylact (P.C. cxxiv, 1065);Google Scholar Calvin (Inst. iv, 6, 5; serm. xv, col. 430); Bengel, J. A. (Gnomon of the New Testament, III, 80);Google ScholarMoulton, and Milligan, (V.G. T. p. 19 ); Abbott, T. K. (The Epistles to the Ephesians and to Colossians) [I.C.C.], p. 146;Google ScholarScott, E. F. (The Epistles of Paul to the Colossians, to Philemon and to the Ephesians) [M.N.T.C.], p. 178.Google Scholar

3 ‘Der, Eckstein’Google Scholar, Angelos, I (1925), 65–70.Google Scholar The interpretation was supported on a number of later occasions: ‘Κεϕαλή γωνλας –' Ακρογωνιαίος’, Z.N. W. XXIX (1930), 264–80; Jesus als Weltuollender (1930), p. 80; ‘Eckstein–Schluβstein’, Z.N. W. XXXVI (1937), 154–7; Ακρογωνιαιος, T. W.N. T. I, 792 f.; λιθος T.W.N.T. IV,277–83.Google Scholar

4 Use was also made of II Kings xxv. 17 (Symmachus), which translates ηℸηℶ (‘chapiter’, R.V., ‘capital’, R.S.V.) by akrogōniaios, and the Peshitta, which renders Isa. xxviii. 16 as ‘head of the wall’.

1 Hanson, S., The Unity of the Church in the New Testament, Colossians and Ephesians (Uppsala, 1946), p. 131.Google Scholar

2 Dibelius, M., An die Kolosser, Epheser, an Philemon (1953, 3rd ed.), p. 72; Schlier, H., Christus und die Kirche im Epheserbrief (1930), P. 49;Google ScholarJeremias, F., ‘Das orientalische Heiligtum’, Angelos, IV (1932), 64f.;Google ScholarCadbury, H. J., The Beginnings of Christianity, v (1933), 374;Google ScholarMichel, O., ναóς, T.W.N.T. IV, 892;Google ScholarVielhauer, P., Oikodome (Diss. Heidelberg, 1939), p. 127;Google ScholarKnox, W. L., St Paul and the Church of the Gentiles (1939), pp. 188f.;Google ScholarHanson, , op. cit. p. 131.Google Scholar

3 Wenschkewitz, H., ‘Die Spiritualisierung der Kultusbegriffe Tempel, Priester und Opfer im Neuen Testament’, Angelos, IV (1932), 178;Google ScholarCerfaux, L., La Théologie de l'Église suivant saint Paul (1948), p. 260; Best, E., One Body in Christ (1955), p. 166. See footnote to Eph. ii. 20 in New English Bible.Google Scholar

4 Percy, E., Die Probleme tier Kolosser- und Epheserbriefe (1946), pp. 329ff., 485ff.;Google ScholarLyonnet, S., ‘De Christo summo angulari lapide secundum Eph. ii. 20’, Verbum Domini, XXII, (1949), 74ff.Google Scholar

5 He excluded this possibility in Angelos, I (1925), 69; Z.N.W. XXIX (1930), 277, n. 3.Google Scholar

6 But not as uncommon as Lyonnet supposes (op. cit. p. 8,).Google ScholarCf., Yalcut Gen. 102Google Scholar to Gen, . xxviii. 22;Google ScholarPirke, R. Eliezer35.Google Scholar

1 Moreover, it scarcely need be pointed out that the whole thrust of gōniaios in akrogōniaios is lost in the keystone idea.

2 Op. cit. p. 164.Google Scholar

3 Cf., Deut. iv. 32; xiii. 8; xxx. 4; Ps. xviii. 7Google Scholar (xix). 6;Jer, . xii. 12;Google ScholarMatt, . xxv. 31.Google Scholar The word is used in the same sense by Aristotle, Polit. IV, 12;Google ScholarPlato, , Phaedo, 109 D.Google Scholar

4 It has this nuance in compounds like άκροθινιον (Hdt. I, 86; Thucyd. I, 132, 2; Heb. vii. 4).

1 Cf., G. H. Whitaker, ‘The Chief Corner Stone’, Exp. XXII (8th ser. 1921), 471.Google Scholar

2 The messianic interpretation of akrogōniaios is already hinted at by the addition of ήπ αūτώ. So also the Targum, which reads: ‘Behold, I have set a king in Zion…whom I will maintain and strengthen.’ On the eschatological use of the text in IQS viii. 4;–11 see below.

3 For a discussion of what the image of the akrogōniaios was intended to convey see Hooke's, S. H. essay, ‘The Corner-Stone in Scripture’, The Siege Perilous, pp. 235 ff.Google Scholar

4 So the editorial insertion, which reads ℸdoubtηℸℸ. Both author and editor alter the wording of Isaiah (note the use of the plurals) to make the reference to the community explicit.

5 Cf., IQS ix. 5f.Google Scholar

6 Cf., D. Feuchtwang, ‘Das Wasseropfer und die damit verbundenen Zeremonien’, M.G.W.J. XI-XII (1910), 10f. and n.Google Scholar; Jeremias, J., ‘Golgotha und der heilge Felsen’, Angelos, II (1926), 95.Google Scholar

1 Yoma v. 2; cf. Leviticus Rabbah xx. 4.

2 Semitic cosmogony, the reader need hardly be reminded, represented the world as emerging out of the primeval morasses. The mountain peaks, because they were first to appear, were naturally regarded as the first things to be created, and as Zion was the mountain par excellence the stone on its summit was given pride of place as the first created thing.

3 The difference of opinion was part of a controversy over cosmological and cosmogonical topics carried on by these two rabbis.

4 Cf., P. Sanh. 29a; also Ex. Rabbah xv. 7.Google Scholar

5 Cf., E. Haupt, Die Gefangenschaftsbriefe (K.K.N.T. 8–9), p. 95, following H. von Soden.Google Scholar

6 The κεϕαλή γωνιας stone of Ps. cxvii (cxviii). 22 is also combined, thus indicating, incidentally, the direct connexion between the teaching of the epistles and that of the early church (Acts iv. 11) and our Lord himself (Mark, xii. 10 and parallels). For the view that Mark, xii. 10; Acts iv. 11; Rom, . ix. 33;Google Scholar Eph. ii. 20; I Pet. ii. 6–8 point to a primitive collection of testimonia on Christ the ‘Stone’ or ‘rock’, cf. at length Selwyn, E. G., The First Epistle of St Peter, pp. 268ff.Google Scholar

1 Yoma, v. 2.Google Scholar

2 Cf. the participles συναρμολογοūμενον (iv. 16) and a συναρμολογουμήνη (ii. 21).

3 Cf., I Kings vii. 13–22; II Kings xxv. 13–17;Google Scholar II Chron, . iii. 15–17; iv. 12–13;Google ScholarJer, . lii. 17–23; also Zech. iv. 7: ‘Zerubbabel…shall bring forward the top stone amid shouts of “Grace, grace to it” (lit. “how beautiful”)!’Google Scholar

4 The equation of the stone and the altar probably owes something to Jacob's altar.-stone (Gen, . xxviii. 10ff.).Google Scholar

5 See at length Wensinck, A. J., ‘The Ideas of the Western Semites Concerning the Navel of the Earth’, V.A.A. XVII, (1916), 1ff.Google Scholar

1 On the rain-making ceremonies associated with the Feast of Tabernacles see Feuchtwang, op. cit.

2 E.g. Yoma, P. V. 3. Cf., John vii. 37f.; Rev. xxi. 6; xxii. 17.Google Scholar

3 The notion was largely inspired by Gen, . xxviii. 17. Yoma, B.54b; Gen, . Rabbali iv. 2;Google Scholar Nu. Rabbah xiii. 4 make the celestial world also evolve from the ebhen shetiyyah!

4 A. Fridrichsen is of the opinion that the akrogōniaios joins two walls of the building (‘Themilios, I. Kor. iii. 11’, T.Z. [1946], p. 316). Is it too fanciful to suppose with Theodoret (P.G. LXXXII, 525) and Calvin (comm. on Eph. ii, C.R. 174–6)Google Scholar that the two walls represent the Jews and the Gentiles? Cf. however Abbott, , op. cit. p. 71.Google Scholar

5 Auxein looks back to akrogōniaios, which, as the navel, is the vital principle of life. Cf. the λιθοιƷωντες I Pet. ii. 5 (Selwyn, , op. cit. pp. 158f.).Google Scholar