Article contents

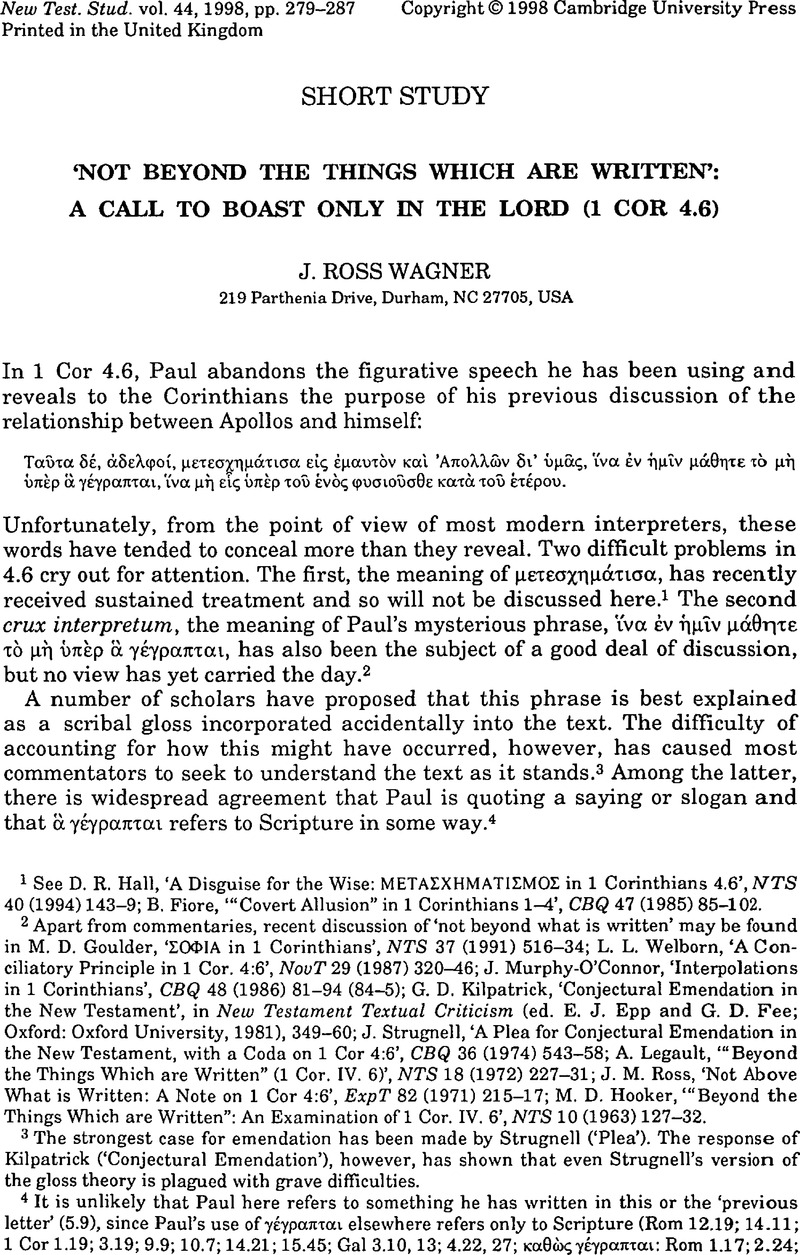

‘Not Beyond the Things which are Written’:A Call to Boast Only in the Lord (1 Cor 4.6)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Short Study

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1998

References

2 Apart from commentaries, recent discussion of ‘not beyond what is written’ may be found in Goulder, M. D., ‘σOφIA in 1 Corinthians’, NTS 37 (1991) 516–34;CrossRefGoogle ScholarWelborn, L. L., ‘A Conciliatory Principle in 1 Cor. 4:6’, NovT 29 (1987) 320–16;Google ScholarMurphy-O'Connor, J., ‘Interpolations in 1 Corinthians’, CBQ 48 (1986) 81–94 (84–5);Google ScholarKilpatrick, G. D., ‘Conjectural Emendation in the New Testament’, in New Testament Textual Criticism (ed. Epp, E. J. and Fee, G. D.; Oxford: Oxford University, 1981), 349–60;Google ScholarStrugnell, J., ‘A Plea for Conjectural Emendation in the New Testament, with a Coda on 1 Cor 4:6’, CBQ 36 (1974) 543–58;Google ScholarLegault, A., ‘“Beyond the Things Which are Written” (1 Cor. IV. 6)’, NTS 18 (1972) 227–31;CrossRefGoogle ScholarRoss, J. M., ‘Not Above What is Written: A Note on 1 Cor 4:6’, ExpT 82 (1971) 215–17;Google ScholarHooker, M. D., ‘“Beyond the Things Which are Written”: An Examination of 1 Cor. IV. 6’, NTS 10 (1963) 127–32.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

3 The strongest case for emendation has been made by Strugnell (‘Plea’). The response of Kilpatrick (‘Conjectural Emendation’), however, has shown that even Strugnell's version of the gloss theory is plagued with grave difficulties.

4 It is unlikely that Paul here refers to something he has written in this or the ‘previous letter’ (5.9), since Paul's use of γέγραπται elsewhere refers only to Scripture (Rom 12.19; 14.11; 1 Cor 1.19; 3.19; 9.9; 10.7; 14.21; 15.45; Gal 3.10,13; 4.22, 27; Кαθὼςγέραπται: Rom 1.17; 2.24; 3.4, 10; 4.17; 8.36; 9.13, 33; 10.15; 11.8, 26; 15.3, 9, 21; 1 Cor 1.31; 2.9; 2 Cor 8.15; 9.9), although his reference to ‘the Scriptures’ is relatively rare (αἰ γραϕαἱ: Rom 1.2; 15.4; 16.26; 1 Cor 15.3, 4; оι γɛγραiμμένоι: Gal 3.10). The variant reading 6 (D F G ![]() ) may have arisen from assimilation to Paul's normal habit of referring to Scripture in the singular or from a belief that he was referring to a particular text (for the latter suggestion, see Welborn, , ‘Conciliatory Principle‘, 324).Google Scholar

) may have arisen from assimilation to Paul's normal habit of referring to Scripture in the singular or from a belief that he was referring to a particular text (for the latter suggestion, see Welborn, , ‘Conciliatory Principle‘, 324).Google Scholar

5 Notes on Epistles of St Paul (London: Macmillan, 1895) 199.Google Scholar The suggestion is also found in Robertson, A. and Plummer, A., The First Epistle of St Paul to the Corinthians (ICC; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1911) 81.Google Scholar Neither work mentions the citations in 1 Cor 2.9 and 16, however.

6 Hooker, , ‘“Beyond the Things Which are Written”’, 130.Google Scholar A similar proposal is made by Ellis, E. E., Prophecy and Hermeneutic in Early Christianity (WUNT 18; Tübingen: Mohr, 1978) 61, 214.Google Scholar

7 Barrett, C. K., The First Epistle to the Corinthians (HNTC; New York: Harper & Rowz, 1968; reprint, Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1987) 107;Google ScholarFee, G. D., The First Epistle to the Corinthians (NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987) 169.Google ScholarGoulder, , ‘σOφIA’, 526Google Scholar n. 27.

8 Welborn, , ‘Conciliatory Principle’, 324 n. 27.Google Scholar

9 Noted by Mitchell, M. M., Paul and the Rhetoric of Reconciliation (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1992) 220 n. 183.Google Scholar

10 Welborn, , ‘Conciliatory Principle’, 325.Google Scholar He quickly dismisses this solution, however.

11 Mitchell, Reconciliation, suggests this solution in a footnote (227 n. 183). P. W. Schmiedel also argues for this interpretation, but adds that Paul's reference here to 1.31 is ‘careless (unvorsichtig)’ and ‘unclear (ungenau)’ (Die Briefe an die Thessalonicher und an die Korinther [HCNT 2; Freiburg: J. C. B. Mohr, 1889] 88).Google Scholar See also Hays, R. B., First Corinthians (Interpretation; Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 1997), 68–9,Google Scholar for a reading of 4.6 along the lines we are proposing here.

12 Welborn, , ‘Conciliatory Principle’, 325.Google Scholar

13 But see note 4 above.

14 Welborn, , ‘Conciliatory Principle’, 325 n. 28 (emphasis his).Google Scholar

15 Ibid., 326. This sentiment was expressed by Strugnell as well;‘… such a reference to Scripture would be irrelevant at this point in Paul's argument’ (‘Plea’, 555; emphasis original).

16 On this see Dahl, N. A., ‘Paul and the Church at Corinth according to 1 Cor 1:10–4:21’, in Studies in Paul (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1977) 54;Google ScholarMitchell, , Reconciliation, 207 n. 113.Google Scholar In Mitchell's analysis, 1.10, ‘The call for unity and an end to factionalism’, serves as the thesis statement for Paul's argument in the entire letter (198–200).

17 Mitchell, , Reconciliation, 219.Google Scholar

18 So Fiore, , ‘“Covert Allusion”’, 93–4;Google ScholarHall, , ‘Disguise’, 147.Google Scholar

19 Fiore, , ‘“Covert Allusion”’, 94.Google Scholar

20 Hall, , ‘Disguise’, 147.Google Scholar

21 For the double ἲνα as a characteristic of Paul's style, see Gal 3.14; 4.5, and the remarks of Robertson, & Plummer, , First Corinthians, 82.Google Scholar

22 ‘Durch (ϕυσιоῦσθαι wird Кαυχᾶσθαι ἐν ἀνθρώπоις (3.21) sachlich erläutert ….’ (Der erste Korintherbrief[MeyerK5; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1910] 104).Google Scholar

23 Mitchell also cites this parallelism of ϕυσιоᾶσθαι and Кαυχᾶσθαι. as evidence for her view that Paul in 4.6 is referring to the quotation in 1.31 (Reconciliation, 220 n. 183).

24 ‘Jeremiah 9:22–23 and 1 Corinthians 1:26–31: A Study in Intertextuality’, JBL 109 (1990) 259–67.Google Scholar

25 This judgment is shared by Hooker, , ‘“Beyond the Things Which are Written”’, 129Google Scholar; Mitchell, , Reconciliation, 212;Google ScholarWelborn, , ‘“Conciliatory Principle”’, 325.Google Scholar

26 Recognized by Lightfoot, , Notes, 169;Google ScholarRobertson, & Plummer, , First Corinthians, 28;Google ScholarSchrage, W., Der erste Brief an die Korinther (1 Kor 1,1–6,11) (EKK 7.1; Zürich: Benziger/ Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1991) 205;Google ScholarKoch, D.-A., Die Schrift als Zeuge des Evangeliums (BHT 69; Tubingen: Mohr–Siebeck, 1986) 35–6.Google Scholar

27 Lightfoot, , Notes, 169;Google ScholarRobertson, & Plummer, , First Corinthians, 28;Google ScholarSchrage, , Korinther, 205;Google ScholarKoch, , Schrift, 36.Google Scholar

28 Hagner, D. A., The Use of the Old and New Testaments in Clement of Rome (Leiden: Brill, 1973) 203–4.Google Scholar See also Lightfoot, , Notes, 169.Google Scholar While for the most part Clement follows the wording of Jer 9.22–3, his citation contains a clause unique to the text of 1 Kgdms 2.10 (Кαὶ πоιɛῖν Кρνμα кαὶ διКαιоσύνην). It is also apparent that he is dependent on Paul's particular wording in 1 Cor 1.31, ὁ Кαυίώμɛνоς ἐКρίῳ Кαυὶάσθω. Clement's quotation may suggest that he recognized in 1 Cor 1.31 a reference to 1 Kgdms 2.10. At the least, it shows that Clement knew both Jer 9.22–3 and 1 Kgdms 2.10 well enough to conflate them with one another and with Paul's distinctive citation of these texts.

29 From this point on, for convenience, I will refer to the text cited by Paul in 1.31 as 1 Kgdms 2.10 rather than writing 1 Kgdms 2.10/Jer 9.22–3. This is not to rule out Paul's use of Jer 9.22–3, but only to observe that no influence of the Jeremiah text independent of the material shared with 1 Kgdms 2 can be established. Although I believe the case for understanding 1.31 as a reference to 1 Kgdms 2.10 is sound, the principal thesis argued in this paper – that Paul's expression in 4.6 refers to the text quoted in 1.31 – would not be materially altered were it shown that Jer 9.22–3 is the only source of the quotation. The majority of the echoes identified below in 4.6–13 hold for both Jer 9 and 1 Kgdms 2, although I believe that the correspondences with 1 Kgdms 2 are more significant and ultimately more illuminating of Paul's thought.

30 Plank, K. A. (Paul and the Irony of Affliction [Atlanta: Scholars, 1987] 47)Google Scholar notes the correspondence between these terms in 4.10 and 1.26, but does not appear to recognize their connection with the OT text cited in 1.31.

31 Paul's use of ϕρόνιμоι in 4.10 actually is closer verbally to 1 Kgdms 2.10 (ϕρόνιμоς) than is his use of σоϕός in 1.26. For the association of ἔνδоξоς with πλоἔσιоς, see Sir 10.22 (a text that appears to echo Jer 9/1 Kgdms 2): πλоύσιоς кαὶ ἕνδоξоς Кαὶ πτωχός τо кαύχημα αὐτῶν ϕόβоς Кυρηоυ (cited in Hagner, , Clement, 204Google Scholar n. 1).

32 In addition, his depiction of the apostles as ᾄτιμоι (4.10), λоιδоρоύμɛνоι,διωкόμɛνоι (4.12), δυσϕημоύμɛνоι (4.13) corresponds to his statement that God has chosen τὰ ἀγɛνῆ, τὰ ἐξоυθη μένα, τо μὴεντα (1.28).

33 Note the emphasis throughout 1 Cor 1–4 on God as giver (1.4, 30; 2.12; 3.5, 8,10,14; 4.5, 7).

- 3

- Cited by