1. Introduction

In the transmission of the text of the New Testament the process of copying was repeated many times. In the course of this process variants in the text emerged in different ways. The textual critic has to think about different kinds of variants (shorter/longer text, different wording etc.) and their possible emergence all through his or her work of trying to reach the initial text. So, the question of the emergence of variants remains an important topic in modern research.Footnote 1 As Dirk Jongkind rightly puts it: ‘In the literature on textual variation in the New Testament there has always been a fascination with the “why?” of scribal variants.’Footnote 2 There have been many assumptions concerning the emergence of variants and observations of certain places of variation or manuscripts, but as Holger Strutwolf states: ‘Eine große Schwäche der bisherigen Textforschung stellt … immer noch die Kriterien- und Methodenfrage dar. Es gibt … bis heute keine empirisch-phänomenologisch fundierte Theorie der Variantenentstehung, die auf der Basis des vollständig erhobenen und kritisch evaluierten Variantenmaterials der Gesamtüberlieferung entwickelt und überprüft worden wäre.’Footnote 3 The INTF's (Institute for New Testament Textual Research in Münster) digital material available on the NTVMR (New Testament Virtual Manuscript Room)Footnote 4 makes this kind of research possible. As Klaus Wachtel says: ‘The digital age finally provides the technical means to accept this challenge [that the sources should be fully taken into account].’Footnote 5 In our project ‘Theory of Variation on the Basis of an Open Digital Edition of the Greek New Testament’ of the Cluster of Excellence in Münster we – Holger Strutwolf, Ulrich Schmid, Troy Griffitts and the author of the present article – examine the emergence of variants in the textual transmission of Acts. A part of studying the emergence of variants is always thinking about what scribes were likely to do, i.e. the aspect of scribal habits. Scribal habits are ‘an integral feature of textual criticism’.Footnote 6 Previous research about scribal habits often focuses on singular readings or Abschriften to detect certain characteristics of a scribe.Footnote 7 Scholars, however, also discuss problems concerning the singular readings method.Footnote 8 Some of the studies using singular readings include the subject of corrections.Footnote 9 Peter Malik studies the topic of corrections more closely and describes the difficulties in interpreting them.Footnote 10 As he rightly says: ‘corrections constitute an important piece in the puzzle of transmission history and as such are well worth closer attention’.Footnote 11 The present article follows his position that it is useful to put more focus on this subject. It shows that observing all corrections in a work of an individual manuscript – in the case of this article the work of Acts – is helpful in order to be able to judge the emergence of specific variants. It presents some exemplary results of the examination of corrections of a few manuscripts of Acts (GA 254, 467, 424 and 61) and shows the importance of the study of corrections in the course of building theories about the emergence of specific variants.

2. Different types of correction

In order to be able to discern and study corrections in a manuscript one first has to think about the question what different types of corrections there are. ‘Type of correction’ is understood as the way in which the correction took place, for example, crossing out something or putting certain reference marks in the text etc. The following paragraph will give a short overview of the types of corrections which one can find in Greek New Testament manuscripts.Footnote 12

In order to delete letters or words correctors marked the deletion by dots above or below the words,Footnote 13 crossed them outFootnote 14 or erased them.Footnote 15 In both of the latter cases the first-hand reading can be difficult to discern. This is also the case when correctors changed letters in words by writing over them, that is, when they changed the letters directly in the words.Footnote 16 There are other types of corrections where it is easier to make out the first-hand reading. Often correctors made insertions between the lines,Footnote 17 or wrote letters or words above the word they wanted to correct,Footnote 18 or marked the word which was in their view false by reference marks above it and wrote the corrected reading in the margin of the manuscript with the same mark.Footnote 19 The correctors also used signs to mark a place where an insertion was needed, and wrote the insertion with the same mark somewhere in the margin.Footnote 20 There are also special signs for alternative readings: one is a connection of γ and ρ and stands for γραφɛται – ‘it is written’ (in a different manuscript or in a text of a church father, for example), the other is the abbreviation ɛν αλλ for ɛν αλλοις, which means ‘in other [places/scriptures]’.Footnote 21 These alternative readings will always be found in the margin. Signs are also used to mark transpositions. In order to correct the word order letters or signs above words are used to mark the correct order, e.g. β α or // /.Footnote 22

In many cases it is difficult, if not impossible, to decide whether the correction was made by the scribe himself or by a later corrector.Footnote 23 In some cases, however, it is most probable that the scribe made the correction himself. That is the case when a word is written – or started, but not completed – then crossed out and written again immediately after, because here we see that the crossed-out word and the correction occur immediately one after the other in the same line, so the correction must have been made in the copying process.Footnote 24 These are called ‘in scribendo corrections’.Footnote 25

3. The Different Character of Corrections in Manuscripts

As Schmid aptly argues in his contribution from 2008, it is profitable for the examination of the emergence of variants to keep in mind the different stages of literary production and reproduction.Footnote 26 The process of correcting a manuscript also belongs into this context. As mentioned above, often it is difficult, if not impossible, to know whether the corrections were introduced by the scribe himself or by a later corrector.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, the places of correction have the advantage that they show definite intervention into the text. We therefore can clearly see an activity of a corrector and deduce hints to his reasons for doing so.Footnote 28 I would not go as far as Jonathan Vroom to say that the corrections ‘reveal the mental operations of ancient scribes themselves, what they were thinking as they reproduced and read texts, and what they viewed as a deficiency or error that needed fixing’,Footnote 29 but I would say they give hints about these processes. And more importantly, the complete examination of all the places of correction in a work in an individual manuscript – here shown in the example of the text of Acts – allows us to make conclusions about the character of the correction and the copying of the first hand.Footnote 30 This is because, on the one hand, it shows what mistakes the first hand is prone to make, which helps the examination of the emergence of specific variants, and, on the other, it reveals the attention of the corrector concerning certain aspects. This will be illustrated with some examples in the following paragraphs. The focus here is not on the content, on how the corrections are spread over the manuscript and in what contexts the corrections lie, as Jakob W. Peterson has it in his study.Footnote 31 The present article is focusing on the different aspects which are corrected and their quantities – changes of letters (some of which are mere orthographic corrections), insertions, substitutions, deletions, transpositions.Footnote 32 In connection with this the question of whether these changes evoke a change of meaning has to be always kept in mind. I am not trying to give an exhaustive examination and study of all the corrections of the manuscripts in this essay, but I will offer a quantitative analysis of the corrections in Acts in a few manuscripts – 254, 467, 424 and 61 – and illustrate the results with a few examples.Footnote 33 This will shed light on the character of the copying of the first hand and the corrections and show how decisions about the emergence of variants at specific places are made possible.

3.1 Minuscule 254

Minuscule 254 is a manuscript from the fourteenth century, which is now located in the National Library in Athens (shelf number EBE 490). It has 453 leaves, 1 column and 42 lines per page and contains Acts, the Pauline Epistles and Revelation. This is a manuscript with commentary. In the manuscript there are 193 places of correction in Acts.Footnote 34 At two places, the first hand is not recognisable so the category of correction cannot be detected. In a great number of the places (141) the corrections change letters in words. In sixty-two of these places clearly false forms (i.e. non-existent forms or forms which create syntactically wrong readings) are corrected. In Acts 2.11/14,Footnote 35 for example, αρβɛς is corrected to αραβɛς,Footnote 36 and in Acts 2.30/26 αρπου to καρπου (this is probably a haplography because it is preceded by the preposition ɛκ). At thirty-eight places the change of letters relates to corrections of minor errorsFootnote 37 such as the exchange of letters which are pronounced in the same way (e.g. in Acts 4.28/20 προωρησɛ is corrected to προωρισɛ) or the deletion or insertion of the movable ν (e.g. in Acts 19.4/34 πιστɛυσωσιν is changed to πιστɛυσωσι). The change of letters pronounced in the same way represents the biggest proportion of the minor changes (eighteen places). The rest of these changes concern words of the first hand which exist and would be possible in the context but are replaced by the corrector. The great portion of obvious errors allows the conclusion that the other cases are also the results of the inattentiveness of the scribe.

Thirty-four places contain insertions of words. Most of them are only small insertions, e.g. of articles, particles or conjunctions. For instance, in Acts 15.28/4 γαρ is inserted by the corrector. Nine of the places of insertions have no correct text in the first hand, either in form or content. In Acts 9.40/34, for instance, a necessary verb, the introduction of speech ɛιπɛν, is left out in the first hand: … και ɛπιστρɛψας προς το σωμα ɛιπɛν ταβιθα αναστηθι … This suggests that here the scribe forgot a word in the course of copying the text, that is, this place shows an error of the first hand rather than a variant of the Vorlage.

The rest of the corrections include seven substitutions, seven deletions and two transpositions. The substitutions show orthographically similar words such as for example διανοια and διακονια in Acts 6.4/14. So, here, it is possible to assume a negligence of the scribe as well. And the case is similar with the deletions, because repeated writings of words or unnecessary additions are corrected, as for example in Acts 19.11/12–24: … ɛποιɛι ο θɛος θɛος δια των χɛιρων παυλου.

The study of the corrections in Acts in this manuscript, therefore, shows that the first hand copied his Vorlage with some inattentiveness or a lack of knowledge of Greek forms. This allows the conclusion that possible variants can have arisen as scribal errors. For, in contrast to obvious errors, orthographically similar words etc. are not immediately visible as errors of the scribe and can be accepted as correct and copied by subsequent scribes.

Another example from this manuscript will illustrate this further. In Acts 22.2/14 there are the variants a προσɛφωνɛι, b προσɛφωνησɛν and c προσφωνɛι. We can see three different tenses – imperfect, aorist and present. Thus, here the textual critic is likely to think about the question which tense is grammatically more correct and whether there perhaps was a development in the language over time. So, it could be a case of which tense the scribe thought was grammatically (more) correct at this certain place so that he wrote it consciously or automatically. In minuscule 254, however, the first hand has variant (c) προσφωνɛι. The corrector inserts an ɛ to form προσɛφωνɛι (variant a) instead. The corrector could have had a different Vorlage or perhaps he had a different grammatical understanding. But, looking at the examination of all the places of correction in this manuscript, a simple scribal error is more probable here. In that case, the scribe has only forgotten one letter, the augment for the past tense. As the scribe has made many morphological mistakes, this is not unlikely. Further, the accent supports this,Footnote 38 because there is an acute above the ω, which is correct in the imperfect, whereas in the present there should be a circumflex above the ɛι.

With the help of the CBGM (Coherence-Based Genealogical Method), which was introduced by the INTF, the relationship between the texts of manuscripts can be examined.Footnote 39 Looking at the potential ancestors of 254, we see that the closest ones have variant a (Fig. 1).Footnote 40 The difference in percentages is not great, but it is a slight support for the assumption that variant c in 254 has emerged as an error for variant a.

Figure 1. Potential ancestors of minuscule 254 (variants shown for Acts 22.2/14)

This example shows well how a variant which is possible and correct in the context can have been created as a scribal error.

3.2 Minuscule 467

Minuscule 467 is a manuscript from the fifteenth century, which is now located in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris (shelf number Gr. 59). It has 331 leaves, 1 column and 21 lines per page and contains Acts, the Pauline Epistles and Revelation. This manuscript is similar to 254 with respect to its mistakes, although it does not have as many. In 467 we find 133 places of correction in Acts. At 113 of these letters in words are changed. Forty-six of these changes are corrections of obvious mistakes, as in Acts 2.46/28, where the first hand wrote μɛταλαμβανον, in which the augment ɛ is not put in instead of the α to create a correct form (the page break between the prefix and the rest of the form might have been the reason for this mistake), or in Acts 4.34/20, where in κητορɛς a τ is missing for κτητορɛς before the correction. Forty-four places of correction concern minor mistakes such as letters which are pronounced in the same way or single/double letters. The high proportion of mistakes suggests that the other places could also be results of the negligence of the scribe rather than variants found in the Vorlage of 467.

In the rest of the places of correction there are nine insertions, six deletions and five substitutions of words. Looking at the nine insertions, it is remarkable that five of them are singular readings in the first hand and most of the insertions are only short.Footnote 41 This together with the other observations suggests that they are the result of the inattentiveness of the scribe as well. The deletions concern one singular reading in the first hand and mostly dittographies and obvious errors. Three out of the five substitutions are singular readings in the first hand and are obvious mistakes, e.g. in Acts 21.37/2–4 the first hand has μɛλλοντɛς, which would not fit into the context and is corrected to μɛλλων δɛ.

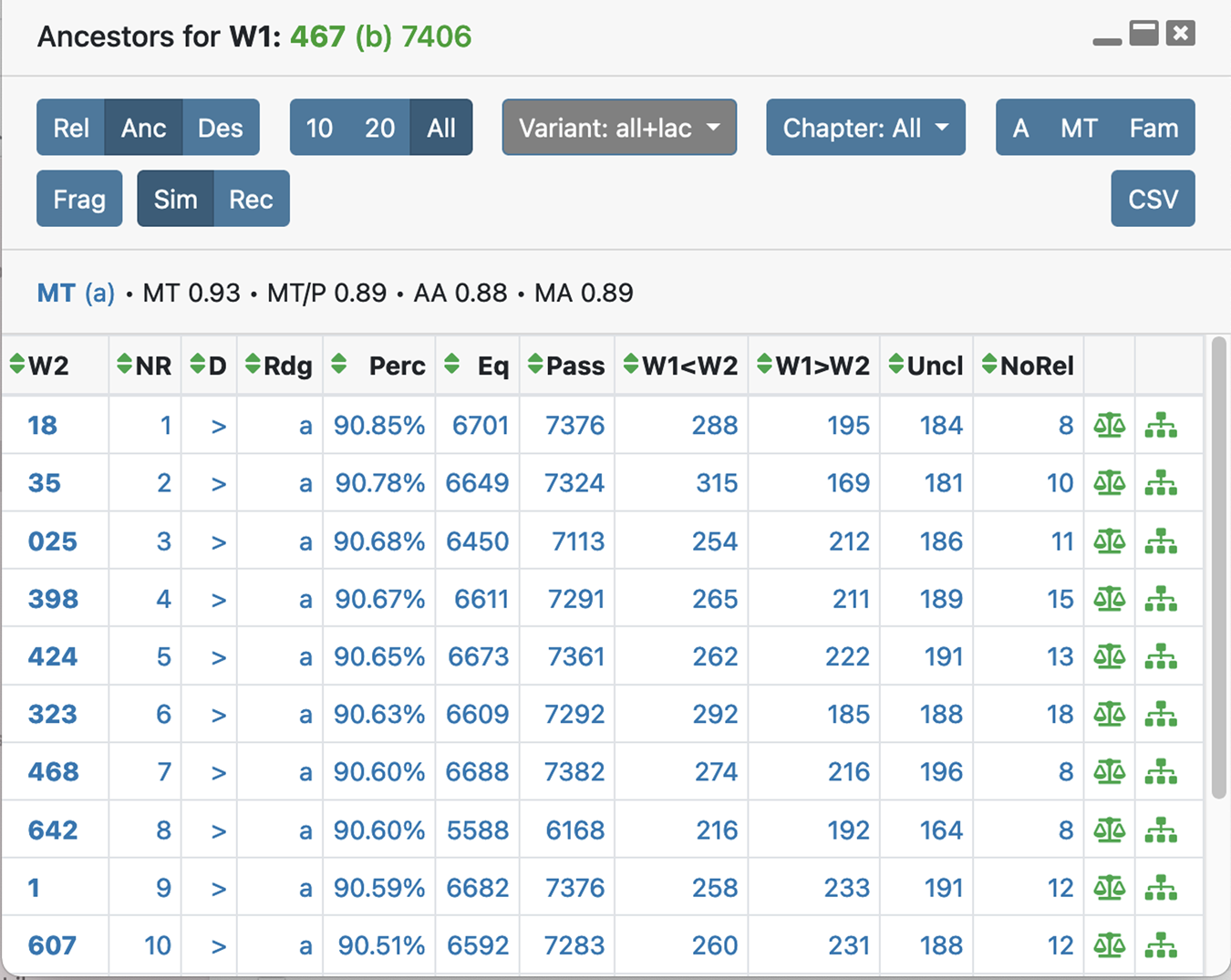

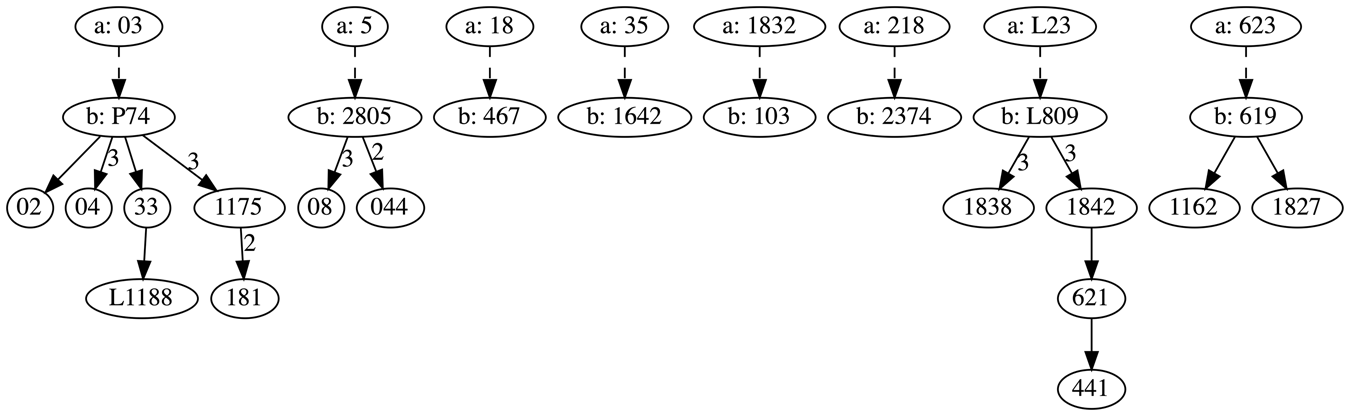

So all these observations lead to the conclusion that the readings of the first hand at the places of correction are probably mostly mistakes of the scribe. This hypothesis helps us to assess individual places of variation. In Acts 13.18/10 the first hand wrote ɛτροφοφορησɛν (variant b), which is a possible word in the context, but is corrected to ɛτροποφορησɛν (variant a). Given the high degree of clear errors in the other places of correction where letters are exchanged, this should also be seen as a mistake of the first hand. A look at the lists of the potential ancestors in the CBGM supports this view: the nearest potential ancestors have reading a ɛτροποφορησɛν (Fig. 2). The coherence at this place of variation shows that reading b probably emerged several times without a connection to other texts which have this reading (Fig. 3). These observations show that it is likely that the variant emerged as a mistake several times.

Figure 2. Potential Ancestors of minuscule 467 (variants shown for Acts 13.18/10)

Figure 3. Coherence in the attestation of variant b at Acts 13.18/10

In Acts 21.25/14 variant b απɛστɛιλαμɛν can also be an easy mistake for variant a ɛπɛστɛιλαμɛν. And again, the possible ancestors of 467 show variant a (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Potential ancestors of minuscule 467 (variants shown for Acts 21.25/14)

Thus, again, the examination of all the corrections helps us to assess individual places of variation. Similar to minuscule 254, in minuscule 467 the character of the corrections supports the view that certain possible variants emerged as errors in this manuscript.

3.3 Minuscule 424

Minuscule 424 is a manuscript from the eleventh century, which is now located in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna (shelf number Theol. gr. 302, fol. 1–353). It has 353 leaves, 1 column and 22 lines per page and contains Acts, the Pauline Epistles and Revelation and also a commentary. This manuscript is different from the manuscripts presented above. It has 267 places of correction in Acts. Twenty-four of those are unclear as most of the time the first hand, twice also the correction, cannot be identified clearly. At nine of those places the category of correction cannot be detected because of this. At most of the places of correction letters are changed in words (127) and words are inserted (66).

Only three times in the case of the changing of letters a clear mistake is corrected – in Acts 5.33/12 the missing λ is inserted into βουɛυοντο, so the correct form βουλɛυοντο is created, and in Acts 13.10/4 and 18.14/44 a superfluous ι is deleted (the relative pronoun ωι, which is wrong in this context, is corrected to the interjection ω). In fifty-seven places corrections of minor errors can be found, such as the change of letters which are pronounced in the same way, e.g. in Acts 24.5/42 ναζοραιων is changed to ναζωραιων. An interesting difference to minuscule 254 is that most of these minor changes in minuscule 424 concern the movable ν (39), so the corrector seems to have a certain focus on this aspect. In all the other places possible variants are found to do with tense, aspect, voice, case, number, orthography, simplex/compound, part of speech (participle/verb), similar words.

The insertions also show possible variations. There is no place where a grammatical or contextual error could be seen before the insertions. At one place the insertion is not readable. The types of insertion vary considerably in terms of parts of speech. Most often pronouns are inserted (twenty), at thirteen places two or more words are inserted (e.g. prepositions with their corresponding case), at nine places the insertion is an article and at eight places it is a conjunction. Once a participle, twice an infinitive, four times an adjective, three times a noun, three times a preposition and twice an adverb can be found.

At twenty-two places of correction text is deleted, at four of which the first hand cannot be read. Only once an error is corrected in these places (in Acts 10.47/33 a superfluous καθως is deleted), at the rest of the places again possible variants can be found. At forty-one places there are substitutions, but in most of these the sense does not change because of that, and two transpositions can be found.

Thus, on the whole it can be seen that the character of the corrections is completely different from that in minuscules 254 and 467. Whereas in 254 and 467 mainly errors (concerning e.g. the form of words) were corrected, the corrections in 424 suggest that the manuscript was corrected against a different Vorlage. As already stated, the manuscript itself is from the eleventh century, but as Wachtel says, ‘[d]ie Handschrift wurde … systematisch nach einem anderen Text korrigiert, der bereits für das 4. Jahrhundert und früher nachzuweisen ist.’Footnote 42

In two places, though, the corrector created readings which can indicate a combination of variants. So, perhaps there was more than one Vorlage for the corrector or he knew other variants which he had in mind while he inserted the corrections. The two places are as follows.

In Acts 3.18/22–28 there are three quite similar variants. They only differ through the use of the pronoun αυτου. Variant a puts it after χριστον: παθɛιν τον χριστον αυτου, while variant b (which is the first hand of 424) has it before παθɛιν: αυτου παθɛιν τον χριστον (It therefore belongs to παντων των προφητων, which is mentioned before that.) The corrector of minuscule 424 inserts αυτου after χριστον, so we get variant c, which on the other hand has αυτου in both places: αυτου παθɛιν τον χριστον αυτου. So, here we see another way in which variants may have emerged: in minuscule 424 variant c could have emerged as a combination of a and b. One reason for this could be that the corrector wanted to emend from variant b to variant a but forgot to cross out the first αυτου, or he wanted to keep both variants.Footnote 43

In Acts 3.11/6 του ιαθɛντος χωλου (variant b) was corrected to αυτου ιαθɛντος χωλου (variant d). This variant, which cannot be found in any other manuscript, could be interpreted as a combination of variant b and variant a (αυτου).

To sum up, the analysis of the corrections in minuscule 424 shows a further possible emergence of variants. Here the character of the corrections is quite different. It is less a correction of mistakes than a revision with the help of another, different, form of the text. The detailed study of all the places of correction supports the conclusion that variants may also have emerged by combining several other variants, a phenomenon which is known and discussed in textual criticism.Footnote 44 Here the variant clearly emerged through the correction with the help of one or more different Vorlagen. The overall study of the corrections suggests this, and the examination of the possible combinations of variants in particular gives more hints in this direction.

3.4 Minuscule 61 or Codex Montfortianus

Minuscule 61 or Codex Montfortianus is a manuscript from the sixteenth century, which is now located in Trinity College, Dublin (shelf number MS). It has 455 leaves, 1 column and 21 lines per page and contains the Gospels, Acts, the Pauline Epistles and Revelation. This manuscript is again a different case.Footnote 45 It has 266 places of correction in Acts. There are ten insertions, twelve deletions, seventeen substitutions and one transposition. Seventy-nine places show changes of letters in words, of which sixteen places are only corrections of minor mistakes in orthography. In 147 places – by far the biggest part – the scribe wrote or at least began to write a word or words, crossed them out and wrote them again, sometimes in a neater way or correcting spelling mistakes. For instance, in Acts 1.14/10 he first wrote ομοθυμαθον, crossed it out and then wrote ομοθυμαδον next to it. It is most unlikely that he wrote both words and someone else crossed out the first later, as it is the same word with an orthographic error. Of these in scribendo corrections 131 are changes of letters in words (seventy-four of those only minor ones), eight are substitutions, six are deletions, one is an insertion and one is a transposition.

The study of all these places of correction helps to assess individual places. For example, there are three places where several words are crossed out – Acts 7.35/23, 7.37/29 and 23.23/23. The question one could ask is whether these are later corrections or corrections the scribe made while copying. At all these places the crossed-out words occur later in the sentence, always after the same word, so the insertion can easily be explained by a parablepsis:

Acts 7.35/23: … τις σɛ κατɛστησɛν αρχοντα και λυτρωτην απɛστɛιλɛν δικαστην ɛφ ημας τουτον ο θɛος αρχοντα και λυτρωτην απɛστɛιλɛν ɛν χɛιρι αγγɛλου …

Acts 7.37/29: … προφητην αναστησɛι υμιν κς ο θɛος υμων ως ɛμɛ αυ ɛκ των αδɛλφων υμων ως ɛμɛ αυτου ακουσɛσθɛ⋅

Acts 23.23/23: ɛτοιμασατɛ στρατιωτας διακοσιους απο τριτης ωρας της νυκτος οπως πορɛυθωσιν ɛως και σαρɛιας, και ιππɛις ɛβδομηκοντα, και δɛξιολαβους διακοσιους, απο τριτης ωρας της νυκτος.

Given that the scribe of 61 crossed out and rewrote words at many places while copying it is quite plausible that he did the same at these places. So, it is more likely that he realised his parablepsis at once and corrected the mistake himself than that it was a later corrector.

In Acts 14.17/16 we see how corrections can give additional information for assessing potential ancestors. In minuscule 61 the scribe began with the letter υ, then crossed it out and wrote ημιν. So, he clearly wanted to write υμιν first, but corrected himself. Both readings are attested in other texts as well. Υμιν is variant a and ημιν is variant b. If we then look at the list of potential ancestors of 61, we see that the closest ones show reading a (Fig. 5). So, normally one could get the impression that reading b emerged from reading a. But if we take the correction into account, the evaluation is different. The scribe began to write υμιν, reading a, but corrected himself. Even considering the fact that υ > η is an Itacism and one can easily be changed to the other, here it should mean that his Vorlage most probably read ημιν, reading b – which at least the seventh potential ancestor of 467 (398) has – because, looking at the other places of correction, the scribe probably was not writing under dictation but was copying from a written exemplar and checked his text while copying (see the parablepses described above). So, in this case the closest potential ancestors are not the most likely source of the variant in this text.

Figure 5. Potential ancestors of minuscule 61 (variants shown for Acts 14:17/16)

In Acts 16.14/32 the character of correction in minuscule 61 helps us to assess a variant reading. Here we see that the scribe first wrote ηνοιξɛ. He then crossed it out and wrote διηνοιξɛ instead. So, he forgot the prefix first. In this manuscript we clearly see that it is a mistake the scribe made and corrected. Ηνοιξɛ is variant c and is read in a few other manuscripts. Looking at the coherence in the attestation of this reading we see that it probably emerged multiple times without a connection between the texts of the manuscripts (Fig. 6). So, it was probably a mistake made by several scribes. The evidence here in minuscule 61 supports the assumption that this reading emerged as a mistake.

Figure 6. Coherence in the attestation of variant c at Acts 16.14/32

4. Conclusion

The article has shown clearly that the examination of individual places of correction with regard to the character of the whole respective manuscript can be profitable for assessing specific variants and their emergence.

By studying all the corrections in a work in a manuscript – and even more so when the whole manuscript can be studied – the character of the copying of the first hand can be detected, e.g. the many morphological mistakes in minuscule 254. Such an examination can then help to assess individual places of variation because the character of the copying of the first hand can indicate that certain variants in manuscripts emerged as simple scribal errors and were copied again because they could not be detected as such. Furthermore, the examples show that the examination of corrections can also bring into focus the character of corrections in a manuscript, for instance the revision with the help of a different Vorlage we have seen in minuscule 424. This can then be useful, for example, for detecting certain variants as a combination of different available Vorlagen.

Therefore, corrections should not be left out of consideration while critically assessing a place of variation. Thus, Barbara Aland's statement ‘wir müssen den Charakter einer Handschrift studiert haben, um nicht zufällige Fehler als bewusste Interpretationen fehl zu deuten’Footnote 46 is supported by the results of this study, and the examination of the corrections of a manuscript is of great help in assessing the character of that manuscript.

A continued study of corrections in manuscripts could offer more evidence for the emergence of variants. A tool on which we are working in our project will be helpful here.Footnote 47 We are tagging the complete ECM text – base text and variants – of Acts morphologically. Each word is marked with the corresponding lemma and the morphology. When this tagging and also a search tool are complete, a search through all the variants will be possible.Footnote 48 It should then, for instance, be possible to search for the insertion of certain parts of speech. Thus, a more thorough study of the corrections of specific manuscripts will become much easier.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S002868852200008X.

Competing interests

The author declares none.