As to Il paria in Poliuto, ignore what they say. I am not the sort of man who does such things! Besides, half of the former is in Anna [Bolena], and the other half in [Torquato] Tasso, and I insist that I am not the sort of man who does such things. Poliuto is entirely, entirely, that is almost entirely new, except the adagio of the primo finale. The rest is all new, and in Naples they have heard too much of my stuff, nor can I do such foolish things.Footnote 1

Writing on 15 July 1838, with these words Gaetano Donizetti reassured his brother-in-law Antonio Vasselli, who had evidently heard rumours insinuating that the score of Poliuto derived much of its music from Il paria. Donizetti's ironic statement – insisting on his creative integrity (not contemplating ‘such things’), while at the same time candidly alluding to his actual recycling of Il paria in Anna Bolena and Torquato Tasso – says much about his aesthetic approach to the practice of self-borrowing against the backdrop of the contemporary discourse on his works. In order to comprehend his words, we must go back to the 12 January 1829, when Il paria had its premiere at the same Teatro San Carlo (Naples), where Poliuto was due to debut in August 1838. The first opera Donizetti wrote as Director of the Royal Theatres in Naples was born under an unlucky star. Not only was it subject to the strict protocol of royal gala premieres – according to which no one in the theatre was allowed to applaud before the sovereign gave the signal – that could easily compromise the opera's success, but, in the nights following the opera's debut, the impresario Domenico Barbaja had also increased the ticket prices, thus disgruntling the audience and reducing attendance. The opera was dismissed after just six performances and, despite his initial, stated intention to revise its score, Donizetti had to put a pin in it, apparently not without regret.Footnote 2 His wish for his first opera to be staged with a tragic endingFootnote 3 emerges in a letter he wrote to his teacher Giovanni Simone Mayr, in which he commented on the audience's response to his subsequent opera for the Teatro San Carlo, Il castello di Kenilworth (6 July 1829): ‘(Between us). I would not give a piece of Il paria for the whole Castello di Kenilworth … Nevertheless. Fate is bizarre.’Footnote 4 In the years following its unfortunate premiere, Donizetti would instead turn to the score of Il paria to make use of the parts that he presumably considered worth giving a second opportunity. As well as in Anna Bolena (Milan, Teatro Carcano, 1830) and in Torquato Tasso (Rome, Teatro Valle, 1833), materials deriving from Il paria are found in Il diluvio universale (Naples, Teatro San Carlo, 1830), Francesca di Foix (Naples, Teatro San Carlo, 1831), La romanzesca e l'uomo nero (Naples, Teatro del Fondo, 1831), Marino Faliero (Paris, Théâtre-Italien, 1835) and Le duc d'Albe (due to be performed at the Académie Royale de Musique in 1840, but left incomplete).

Donizetti's repeated recycling of bits and pieces of Il paria must be read within the context of the nineteenth-century Italian operatic system, whose hectic schedules did not allow composers to indulge on their works beyond the time that was strictly necessary. The idea of an established repertory was only gradually emerging, fostered by the dissemination of Gioachino Rossini's works. Examining the latter's practice of self-borrowing, Marco Beghelli interprets it primarily as a ‘self-preservation instinct’, dictated by the composer's conviction that ‘high-quality musical materials had to be given their proper value, if contingent factors had prevented them from circulating’.Footnote 5 An analogous ‘self-preservation instinct’ must have guided Donizetti in his cannibalization of Il paria and, in the following years, of Imelda de’ Lambertazzi (Naples, Teatro San Carlo, 1830), Francesca di Foix, and Ugo, conte di Parigi (Milan, Teatro alla Scala, 1832), all united by an initially cold reception, which, in early-nineteenth-century Italy, almost always translated into an irreversible disappearance from the theatrical circuits. Before it was unexpectedly rehabilitated in numerous productions across the peninsula, Maria de Rudenz (Venice, Teatro La Fenice, 1838) was to follow a similar path, which brings us back to the letter quoted at the beginning of this text. The ‘adagio of the [secondo] finale’ of Poliuto (erroneously indicated as the ‘primo finale’), ‘La sacrilega parola’, in fact derives, with slight modifications, from the slow section of the Finale primo from Maria de Rudenz, ‘Chiuse al dì per te le ciglia’. Donizetti's words to Vasselli could therefore be paraphrased as follows: when composing a new opera, it was not his habit to unconscientiously bundle earlier fragments into a patchwork;Footnote 6 however, there were cases when he recast ideas from previous works, mostly unsuccessful ones, providing – I would argue – the conditions allowed for such a re-use. Proof of this lies in the chronological distance that could separate some of the source pieces from their second life. This is the case, for example, with Zarete's aria from Il paria, which re-emerged in Le duc d'Albe more than ten years after its composition.

There is one last aspect of Donizetti's letter to Vasselli that deserves closer attention, that is, the allusion to the Neapolitan audience's prior knowledge of ‘too much of his stuff’, which might have fed the rumour about the alleged re-use of Il paria into his new score. As Emanuele Senici has recently shown, ‘discussion about self-borrowing as a practice distinct from plagiarism emerged only in the early 1810s’, mostly in relation to Rossini.Footnote 7 This phenomenon is interlaced with the contemporary delineation of the concept of personal style – which, in order to be identified as such, must display internal recurrences – and with Rossini's style in particular, which is based on repetition on several levels.Footnote 8 Interestingly, the narrative of the earliest accusations of self-imitation to fall on Donizetti inevitably included more or less nuanced references to Rossini.Footnote 9 Yet in 1829 a reviewer resorted to a parallel with the Pesarese to justify Donizetti's presumed recycling of old ideas:

Some people, not without reason, argue that there are imitations of renowned motifs; but if this is a flaw, we wonder in which modern music it is not encountered: who has studied in depth German music does not grant the merit of originality except to a few of pieces by Rossini himself.Footnote 10

The latter article, opposing the intrinsic repetitiveness of ‘modern music’ to German music, refers to Il castello di Kenilworth, whose score appears not to contain cases of self-borrowing. The dividing line between the individuation of self-borrowing and the perception of a composer's style was very subtle and – much like what happened with Rossini – accusations of self-imitation in the press rarely corresponded to actual cases of recycling.Footnote 11 During the 1830s, as Donizetti was developing his own musical language, reviewers repeatedly reported the presence of vague ‘reminiscences’ from his previous works, which, however, were never explicitly named. When Lucia di Lammermoor premiered at the Teatro San Carlo, on 26 September 1835, the reviewer in I curiosi offered an artistic comparison between music and painting in response to the composer's detractors accusing him of self-imitation, which puts the question into focus:

Every composer has his own style, like painters have their own manner to paint. And if Raffaello's works can be distinguished from those of Michelangiolo, and these by those of Correggio, isn't it because each of these great artists used to have his own way of painting? Similarly, the musical works of the great maestri differ from each other for their diverse style, and it cannot be said that a maestro imitates when he writes according to his own system.Footnote 12

It comes as no surprise that many of the accusations originated in those areas where Donizetti's works had been circulating most intensively and, in particular, in Naples, whose theatres hosted the premiere of about 30 of the operas he composed for Italy, and where people knew ‘too much of [his] stuff’. As emerges clearly from his letter to Vasselli, Donizetti was perfectly aware of the system in which he was operating as well as the discourse surrounding his works, which might have in turn influenced his conception of self-borrowing.

By examining selected case studies from his versatile production, which unfolded over three decades and was staged in the foremost Italian and European theatres, this article questions Donizetti's self-borrowing as a chiefly economic practice, offering novel keys to reading his re-use of existing materials. I will first look at his self-borrowings across genres, dwelling on the ways in which he re-functionalized earlier serious passages within comic frames, almost inevitably to achieve a parodic effect. After discussing the links between parody and diegetic music – one of his favourite contexts for employing older materials – I will turn to Donizetti's serious production, advancing the hypothesis that his recourse to self-borrowing could take on semantic connotations. In so doing, in the second part of the article I will focus on examples grouped into three thematic areas, which – similarly to, and occasionally in connection with diegetic music – all involve the suspension of a character's habitual idioms: deception, rituals and madness. My ultimate concern is to demonstrate that Donizetti's use of self-borrowing could perform a dramatic function, deliberately connoting the altered modes of expression of the characters to which they are associated.

(Self-)Parody

In his recent book on Rossini, Emanuele Senici discusses the composer's practice of self-borrowing in relation to genre, observing that ‘self-borrowing across genres is decidedly frequent, even if probably not the norm’. Senici notes that whereas ‘opere serie borrowed mostly from other serie’, opere buffe ‘seem less genre specific in their helpings’, individuating in cabalette and strette a privileged context for the cross-migration of earlier materials. This tendency appears to be linked to Rossini's peculiar dramaturgy, entailing a distance between operatic representation and reality, and thus ‘blurring the distinction across genres’.Footnote 13 Although self-borrowings across genres are decidedly frequent even within Donizetti's production, their aesthetic premise is rather rooted in his Romantic dramaturgy, which was based on a representational distinction between – and characterization of – genres, moving towards a greater adherence to reality, before aspiring to bring them together. In fact, Donizetti's (self-)borrowings across genres tend to follow a trajectory leading from the serious to the comic,Footnote 14 and, more significantly, they appear to inevitably serve a more or less nuanced parodic purpose, whereas the degree of parodization depends on the level of recognizability of the earlier piece, which may at times be derived from a work by a different author. Within the context of this article, by parody (and self-parody), I am referring to a specific subcategory of re-use of earlier materials, generally entailing a modification of the music and/or the verbal text (or some aspects of them) to produce a comic effect, occasionally – but not necessarily – ridiculing the source piece.Footnote 15 The comic effect may at times derive solely from the incongruity between the parodied piece and the new dramatic context in which it is re-employed, and it may take place regardless of the audience's knowledge of the prior piece. As it will be discussed in detail later within this article, it is significant that Donizetti limited the majority of his (self-)parodied pieces to the aesthetic realm of diegetic music – here intended as ‘music heard as music’ – which, in some cases, can in turn involve a metatheatrical performance.Footnote 16

The most obvious case is offered by Le convenienze ed inconvenienze teatrali (Naples, Teatro Nuovo, 1827), a one-act dramma giocoso with spoken dialogues satirizing the contemporary operatic system, to a libretto by Domenico Gilardoni. Although no autograph score survives, an evaluation of its extant sources suggests that the opera's first version included the protagonist's aria di sortita from Donizetti's Elvida (Naples, Teatro San Carlo, 1826), as well as the ‘Canzone del salice’ from Rossini's Otello (Naples, Teatro del Fondo, 1816), followed by the cabaletta ‘Or che son vicino a te’ from Giuseppe Nicolini's melodramma Il conte di Lenosse (Parma, Teatro Ducale, 1801).Footnote 17 Elvida's aria, ‘Ah! Che mi vuoi? Che brami’, is pretentiously presented in the Introduzione by Corilla, the prima donna of a sloppy company rehearsing a serious opera, which the Neapolitan audience could identify as Donizetti's work that had premiered at the Teatro San Carlo just one year earlier. ‘Ah! Che mi vuoi? Che brami’ had also been published as a pezzo staccato, which allowed it to circulate even more widely. In the second part of the opera, the seconda donna's mother, Agata (an atypical buffo en travesti), offers to replace the primo musico, who has just abandoned the company. She then delivers a comic version of the then-celebrated ‘Canzone del salice’, whose words – and music – she keeps misremembering, its opening line becoming ‘Assisa a piè d'un sacco’ (‘Seated at the foot of a sack’). The following piece by Nicolini, which was regularly inserted in other composers’ works during the 1820s and 1830s, is clumsily distorted and enriched with passages of falsetto.Footnote 18 All (self-)parodied pieces are therefore explicit quotations from earlier, serious pieces that were familiar to the audience for whom the opera was intended, and whose mangled renditions would inevitably produce a comic effect. Additionally, their resurgence within a metatheatrical scene of an opera satirizing opera – with opera singers interpreting opera singers – provides the audience with clear signals of the presumable presence of a quotation from an earlier, operatic piece.

Further cases can be found in the score of Il campanello (Naples, Teatro Nuovo, 1836), a one-act farsa with spoken dialogues for which Donizetti was the author of both the libretto and the music. Based on the vaudeville La sonnette de nuit (Paris, Théâtre de la Gaité, 1835), the opera opens with the celebrations for the marriage between Serafina and the apothecary Don Annibale Pistacchio, who must leave for Rome the following morning to collect his aunt's inheritance. The celebrants are soon joined by Enrico, Serafina's former lover, who comes up with a plan to prevent the marriage from being consummated, also relying on Don Annibale's legal duty to make his products available even at night. As early as his first appearance on stage, Enrico presents himself as an untrustworthy person, who has betrayed Serafina in the past and is ready to resort on his acting – and lying – skills to get her back: he firstly tries to convince her that he will die out of love if she rejects him, and, as soon as he realizes that Serafina no longer believes him, he threatens to kill Don Annibale. In the following scenes, Enrico's acting reaches a higher degree of metatheatricality. When Don Annibale and his guests surprise him kneeling at Serafina's feet, he gets by pretending that he was rehearsing an unspecified ‘scene’. In the opera's original version, at Don Annibale's request, Enrico is forced to improvise a ‘tragedia in 25 atti con monologo, prologo, epilogo, riepilogo, ed a piccole giornate’ (a tragedy in 25 acts with monologue, prologue, epilogue, summary, divided into short days), implicitly satirizing Romantic theatre. When, the following year, he revised the opera for the Teatro del Fondo and was therefore requested to replace the spoken dialogues with recitatives, Donizetti interpolated a parodied version of the opening phrases from Rossini's ‘Canzone del salice’. Here its first line becomes ‘Assisa a piè d'un gelso’ (‘Seated at the foot of a mulberry’). It is then the time for Enrico to sing a ‘certa canzone che in Milano appresi’ (‘certain song I had learned in Milan’) in order to prolong the party, which is no more than Maffio Orsini's brindisi ‘Il segreto per esser felici’, from Donizetti's Lucrezia Borgia, actually premiered in Milan in 1833. In the 1837 revision, Donizetti replaced ‘Il segreto per esser felici’ with Il bevitore, a brindisi he had newly published as part of the collection of chamber music, Nuits d’été à Pausilippe (1836). After all the guests have left and Don Annibale is finally ready to reach his spouse, the concluding part of the opera is articulated as a succession of gags staged by Enrico to ‘suspend time’, thus preventing the newlyweds from being alone.Footnote 19 In the second gag, he is disguised as an opera singer looking for a remedy against hoarseness. As he pretends to take the medicine offered to him by Don Annibale, Enrico tests his voice by singing the gondolier's barcarola, ‘Or che in ciel alta è la notte’, from Donizetti's own Marino Faliero (Paris, Théâtre-Italien, 1835). Like the previous example, Il campanello includes a comic re-functionalization of prior, serious pieces, at least one of which was by a different composer. Unlike that, however, this opera alternates earlier pieces whose parodies would be immediately recognizable, including the brindisi from Lucrezia Borgia in the opera's first version, and the ‘Canzone del salice’ in its 1837 revision, with others that would be less familiar, such as the gondolier's barcarola from Marino Faliero, which had not yet been staged in Naples, and Il bevitore.Footnote 20 Before delving into the implications of the source pieces’ lesser – if not null – recognizability, it is worth embarking on a journey to Paris.

The two works examined so far both belong to the tradition of comic operas with spoken dialogue, which was remarkably vivid in early-nineteenth-century Naples (and, in particular, at the Teatro Nuovo),Footnote 21 and also had roots in French opéra comique.Footnote 22 Writing on La fille du régiment (Paris, Opéra-Comique, 1840), the composer's first actual test of opéra comique, William Ashbrook defined Marie's ‘chant du régiment’ (‘Chacun le sait, chacun le dit’) as ‘one of Donizetti's more improbable self-borrowings’, evidently referring to the distance from its source opera, Il diluvio universale (Naples, Teatro San Carlo, 1830), in terms of time span, genre and destination.Footnote 23 Nevertheless, Donizetti's compositional strategies for the comic works ‘alla francese’ he had written for Naples – including his consolidated practice of parodization of prior, serious pieces – offer a relevant context against which to re-examine the piece. The opera takes place at the time of the Napoleonic wars, and Act 1 is set on the mountains of Tyrol; Marie is an orphan who was found as a child on the battlefield, and adopted by the soldiers of the Twenty-First Regiment of the French army. At her first appearance on stage, in her duet with Sulpice (the Regiment's sergeant), she claims she would be ready to march to the battlefield and join the fight: Marie possesses the heart of a soldier (‘Et comme un soldat j'ai du cœur!’), and the – feminine – role of vivandière she proudly purports to have been granted ‘à l'unanimité’ (‘unanimously’), as a proof of her capacity, does not seem to deflate her unbecoming military ambitions. Marie sings the ‘chant du régiment’ later in Act 1, at the request of Sulpice, to celebrate Tonio (her Tyrolean lover) for having saved her life. After a virtuosic cadenza marking the passage to diegetic music, Marie sings the two couplets constituting the song, each of which opens with a martial sentence (a 4 a′ 4 b 4) sustained by a light accompaniment in the strings (Martial, F major, 4/4), and is followed by a waltz-like section (Allegro vivace, F major, 3/8) that is immediately repeated by the chorus of soldiers. The martial sentence with which Marie sings the praises of the Twenty-First Regiment has its roots not only in Donizetti's aforementioned azione tragico-sacra, Il diluvio universale, but also – before that – in the composer's unfortunate dramma per musica Alfredo il grande (Naples, Teatro San Carlo, 1823). In the older score, the sentence coincides with a march played by a banda sul palco accompanying the arrival of the Danish troops at the end of the Introduzione.Footnote 24 In Il diluvio universale, it is at the core of the stretta (‘Sì, quell'arca nell'ira de’ venti’) from the Act 1 Introduzione, during which Noè foresees that his ark will save ‘the just man’, in response to Cadmo's followers’ attack. Its melodic line (Maestoso, C major, 4/4) is almost identical to its regimental version, but in Il diluvio universale it is solemnly accompanied by the winds. The ‘chant du régiment’ reappears during Marie's singing lesson in Act 2, set in the castle of the Marquise de Berkenfield, who has taken the girl to live with her, claiming to be her aunt (though, by the end of the opera, she will reveal herself to be Marie's mother). The singing lesson scene features an additional earlier piece: while accompanying Marie at the piano, the Marquise urges her to sing a ‘romance nouvelle, d'un nommé Garat, un petit chanteur français’ (‘a new romance by someone named Garat, a minor French singer’), which the Parisian audience would identify as a parodied version of the air de salon by Pierre-Jean Garat ‘Le jour naissait dans le bocage’. As she lazily sings it, Marie is distracted by Sulpice, prompting her military songs. Marie's performance gives way first to a rataplan and then to the second part of the ‘chant du régiment’, before exploding in a succession of scales and arpeggios. The reprise of the ‘chant du régiment’ within the singing lesson builds a long-distance bridge between the two pieces, which both emerge as parodies. However, whereas Donizetti's re-use of Garat's song provides his French audience with a recognizable model, this is not the case with the ‘chant du régiment’, whose predecessor could not be acknowledged (similarly to what has already been observed with Il campanello). Here the discourse shifts – at least in terms of reception – from the parody of a specific piece, to the parody of a musical style broadly speaking, characterized by stereotyped features. By re-employing the earlier theme from Il diluvio universale in La fille du régiment, Donizetti in fact offered the audience a parody of the martial style the piece belonged to, here re-negotiated in a comic way through its incongruous combination with the voice of a young girl (a virtuosic soprano) raised by a bunch of French soldiers, celebrating their Twenty-First Regiment, ‘le seul à qui l'on fasse crédit / dans tous les cabarets de France’ (‘the only one given credit / in all the taverns of France’), and aspiring to join them on the battlefield. Further cases can also be found within the composer's most popular comic operas.

In L'elisir d'amore, Donizetti employed earlier, serious pieces to accompany the entrances of both Belcore and Dulcamara. As is well-known, Belcore's cavatina, ‘Come Paride vezzoso’, explicitly recalls ‘Come un'ape ne’ giorni d'aprile’ from Rossini's La Cenerentola (Rome, Teatro Valle, 25 January 1817), which the valet Dandini sings to present himself disguised as Don Ramiro, the Prince of Salerno, at the house of Don Magnifico. What is lesser known is that the march opening it derives from Donizetti's own Alahor in Granata (Palermo, Teatro Carolino, 1826), where it anticipated the triumphal return of King Hassem (a heroic contralto en travesti). Donizetti trivialized its orchestration to depict the character's vulgarity: the elegant, light accompaniment of the winds gives way to the percussion, which bombastically punctuates the strings. The piece is introduced by the prolonged roll of a diegetic drum off-stage, drawing the audience's attention on the military parade. Similarly, later in the first act, Dulcamara's cavatina is prepared by a solo trumpet announcing his arrival. Attracted by the sound of the diegetic instrument, the villagers gather on stage, singing the choral section which anticipated the entrance of Queen Elisabetta in Il castello di Kenilworth. As Federico Fornoni has recently highlighted, Elisabetta's arrival was signalled earlier, in the preceding duet of Amelia–Warney by two trumpets, which reappear right before the aforementioned chorus, while the Royal cortège proceeds, so as to ‘establish a “realistic” sonic definition of the celebratory pomp’.Footnote 25 Whereas in its serious predecessors the ‘timbral-spatial effect serves to outline the characters’ traits’,Footnote 26 the trumpet opening Dulcamara's cavatina and, retrospectively, the drum anticipating Belcore's entrance contributes to constructing the characters’ masks (in the case of Belcore, the mask is further refined by means of the verbal-musical allusion to Dandini's cavatina), at the same time satirizing a stereotypical model. Although the quotation is not literal, another case in point is the Notturno ‘Tornami a dir che m'ami’ that Norina and Ernesto sing in the third act of Don Pasquale (Paris, Théâtre-Italien, 1843) in order to set a trap for the opera's protagonist. The melodic line recalls the love duet ‘Tu, l'amor mio, tu l'iride’ from the Prologue of Caterina Cornaro, which Donizetti had completed between 1842 and 1843, but which would not receive its premiere until 12 January 1844, at the Teatro San Carlo (after Don Pasquale). By abundantly enriching the duet's melodic line with a plethora of chromaticisms, embellishments, portamenti and intervals creating specific effects (including the ascending major sixth at the words ‘[mi] chiami’ (‘you call me’)), Donizetti parodies typical sentimental emblems, within the context of a number involving a metatheatrical performance. As they sing their Notturno within the fictive context of the opera, Norina and Ernesto are also acting to the detriment of Don Pasquale, which leads us to our next point.

Diegetic Music and Altered Modes of Expression

As mentioned earlier, the examples discussed so far are indicative of a persistent tendency: in at least five cases, the (self-)borrowed pieces appear in their original context as diegetic music; and in almost all cases (except the two examples from L'elisir d'amore, both involving the sound of diegetic instruments), they are re-elaborated as diegetic music in their second, comic destination. In his pioneering study on the dramaturgy of Italian opera, Carl Dahlhaus describes diegetic music as ‘interpolated music’, which emerges as a quotation, an intrusion ‘from another world outside […] in a context where music is the language of the drama's entire world’.Footnote 27 Two years later, in an article addressing its various dramaturgical functions, Luca Zoppelli proposed a narratological study of diegetic music, in the wake of Mikhail Bakhtin's theories of the modern novel. According to Zoppelli, the ‘dialogic’ nature of the modern novel presents analogies with operatic discourse: in an opera, musical expression is in fact determined by ‘an interaction of the author's discourse with the fictive [i.e. pertaining to fiction] discourse of the characters’. Within this dialectic relation, there are cases involving an ‘abdication of the author’ – which translates into a ‘suspension of the composer's “narrative” responsibility’ – among which Zoppelli sees diegetic music. In other words, the audience perceives the passages of diegetic music as ‘products of the characters, as events determined by them and not by the composer, who gives them voice but remains separate from them’.Footnote 28 Narrowing our discussion to Donizetti's production, in the same book quoted previously, Fornoni explores the composer's intensive use of diegetic music against the wider backdrop of the sonic spatialization of his theatre. After examining examples of diegetic music from Lucrezia Borgia, Linda di Chamounix, Poliuto and La favorite, Fornoni notes that the audience's attention is attracted also by the fact that the pieces at issue have ‘a timbral characterization foreign to the ordinary, operatic code’.Footnote 29

Turning back to Donizetti's self-borrowings across genres, we may conclude that they are frequently circumscribed within passages of diegetic music that are somehow foreign to the ongoing musico-dramatic discourse, within ‘interpolated music’, which the audience tends to perceive as a product of the characters, and in which the discourse of the composer takes a step back. In their new context, the earlier materials Donizetti had composed for a different work – where they may have also fallen inside his narrative responsibility – would therefore undergo a process of parodic re-functionalization. There is, however, one additional aspect that requires further discussion. Within the restricted space of diegetic music, the character is offering a performance within the performance, which implies a further degree of fiction, as well as – I argue – a suspension of the character's usual modes of expression. When Enrico sings the gondolier's barcarola, he adopts a foreign idiom in order to fool Don Annibale. Before she finds her own voice, Marie sings through the martial ways of her adoptive fathers and, later, through the mannered ways of her rediscovered mother. We may thus say that both Enrico and Marie are resorting to altered modes of expression, for which I propose the locution ‘metafictive modes of expression’. The intent behind Donizetti's re-use of earlier, serious pieces within a comic context is self-evident: regardless of the prior piece's recognizability, Donizetti quotes a genre that is foreign to the one within which it is re-employed, and which becomes the object of his parody. Donizetti's treatment of self-borrowing across genres calls, however, also for a reconsideration of the use of pre-existing materials within his serious production, where it often signals a different sort of departure from the character's usual modes of expression.

Deception and Forgiveness

Compared to the examples discussed so far, in Linda di Chamounix, Donizetti's first opera for the Kärntnertortheater in Vienna (1842), the interconnection between diegetic music and self-borrowing is less evident. A melodramma semiserio in three acts, Linda derives its subject from the French play La grâce de Dieu, ou La nouvelle fanchon by Adolphe-Philippe d'Ennery and Gustave Lemoine.Footnote 30 Donizetti had seen the play himself, as he wrote to Vasselli in a letter presenting the planned layout of the opera:

It's about youths who leave Savoy for Paris in order to earn their bread. […] One girl is several times on the point of allowing herself to be seduced, but each time she hears the song of her native land, thinks of her father and mother, and resists … Then she no longer resists … Her seducer wants to marry someone else. Then she goes mad (humph!); she returns home with a poor boy [Pierotto] who encourages her to keep walking by playing her the song: he does not, she stops … Both of them nearly die of hunger; the seducer arrives … he did not get married. The girl recovers, because when hearing this, a woman recovers immediately.Footnote 31

Linda's actual plot diverges from Donizetti's original outline in at least one crucial aspect. Unlike the protagonist of La grâce de Dieu, Marie, Linda never succumbs to the seducer's temptation, and thus preserves her chastity.Footnote 32 The centrality of diegetic music in this opera dates back to the original play, which in turn dramatizes the then-popular song ‘À la grâce de Dieu’ (1835), composed by Loïsa Puget to a text by her husband, Lemoine. The song is introduced by the protagonist's mother as a farewell before Marie leaves for Paris, sounding as a premonition of the events to follow. In the course of the play, it will subsequently serve a therapeutic purpose: after Marie loses her mind, Pierotto is unable to calm her down until he goes off-stage, and plays ‘À la grâce de Dieu’ with his hurdy-gurdy, at whose sound she starts following him; once he has brought her back to Chamounix, Marie finally regains her mind by re-hearing the song performed by the voice of her mother. In Donizetti's opera, the function of the song as it was originally designed in the play is split between two different pieces: Pierotto's ballata ‘Per sua madre andò una figlia’, which he sings before they travel to Paris, and the cabaletta of the Act 1 love duet Linda–Carlo, ‘A consolarmi affrettisi’. When Carlo tries to seduce her, Linda is able to resist as she hears the ballata which Pierotto is playing down in the street (or which, in Fornoni's opinion, ‘resounds only in the girl's mind’Footnote 33) and, like in the play, the young Savoyard succeeds in making her walk towards Chamounix by incessantly playing it on his hurdy-gurdy. Nevertheless, Linda regains her mind only when she hears Carlo replicating the cabaletta theme in the opera's final scene, which requires further discussion.

The cabaletta from the Act 1 love duet recurs many times throughout the opera before becoming the catalyst of Linda's recovery. When the duet takes place, the Viscount Carlo's real identity has not yet been revealed, as Linda is still convinced that he is a painter and he is going to marry her as soon as he is granted a position. The duet is structured in the so-called ‘solita forma’: in the primo tempo, we learn that the two lovers have been having a secret, daily rendezvous since the first day they met, but a mysterious reason prevents Carlo from marrying Linda; in the cantabile, they agree that the hardest thing for two lovers is to keep their love secret and to stay apart; in the tempo di mezzo Carlo promises Linda that this situation will soon come to an end, implying that he will marry her, and giving rise to the cabaletta. The latter expresses the two lovers’ impatience for the day they will be married and entails a mutual promise (see Table 1). Here I wish to emphasize that the union to which they aspire requires a double legitimation, by heaven (‘innanzi al ciel’, whereby the latter word appears no fewer than 30 times in the printed libretto) and by the people (‘agli uomini’), that is by the community. The cabaletta theme first recurs in the Parisian act, as a result of Linda's madness: after being cursed by her father, Antonio, her first musical reaction is to sing its beginning, during which she ‘va serenandosi’ (‘she becomes calmer’). At the words ‘tua sposa diverrò’ (‘I shall be your wife’), however, she cannot carry on, and takes refuge in a repeated E-flat, against a G major backdrop, before turning to the cabaletta ‘No, non è ver, mentirono’ – the only new musical material she is able to produce after losing her mind. Linda ideally concludes the phrase no earlier than Act 3, when she is back in Chamounix, resuming the melodic line where she had left it in her mad scene, but in F major.Footnote 34 Pierotto's annoyed reaction to Linda's ‘mechanical’ repetition of the cabaletta theme informs the audience that she has been obsessively replicating it since the moment she lost her mind. Linda's recurring repetition of the theme, which Pierotto can perceive (‘E via! Sempre lo stesso’ (‘Come on! Always the same!’)), retroactively connotates the cabaletta as diegetic music.Footnote 35

Table 1 Gaetano Donizetti, Linda di Chamounix, Act 1, No. 3 Scena e Duetto di Linda e Carlo, cabaletta (verbal text)

Carlo's final repetition of the theme further reinforces this supposed ontological status of the cabaletta. When he joins her – unmarried – in Chamounix, Linda admits that a similar voice had flattered her in the past, but she rules out that it can belong to ‘her’ Carlo, as he would have comforted her heart with ‘un caro accento, / che rammenta il più bel dì’ (‘the dear accent, / which recalls our happiest days’). Understanding what she is referring to, Carlo re-enacts the theme of the cabaletta in the original key of G major, at the sound of which Linda regains her mind. The printed libretto for the opera's premiere (A-Wn) presents the following stage direction accompanying Carlo's part: ‘Linda riconoscendo il canto lo segue, lo ripete [con] ansia, confusa poi dalla viva repente emozione va mancando, e sviene in braccio di Maddalena, sorretta da Antonio, e dal Visconte’ (‘Linda, recognizing the song, repeats it with anxiety, then confused by the sudden emotion she swoons, and faints in Maddalena's arms, sustained by Antonio and by the Viscount’). When transferring it from the libretto to his autograph score – as it was his habit – Donizetti included only a contracted version: ‘Linda lo ascolta con tutta l'attenzione’ (‘Linda listens to him with all her attention’).Footnote 36 Providing that, in this specific case, Donizetti's omission of the explicit reference to a song (‘canto’) is intentional, it can be argued that, though not diegetic music, the cabaletta has a ritual function: it is a private, shared promise, whose words constitute a specific formula. In order for Linda to recover, Carlo's voice in itself is not enough, nor are his ‘flatteries’: she demands to listen their mutual promise.

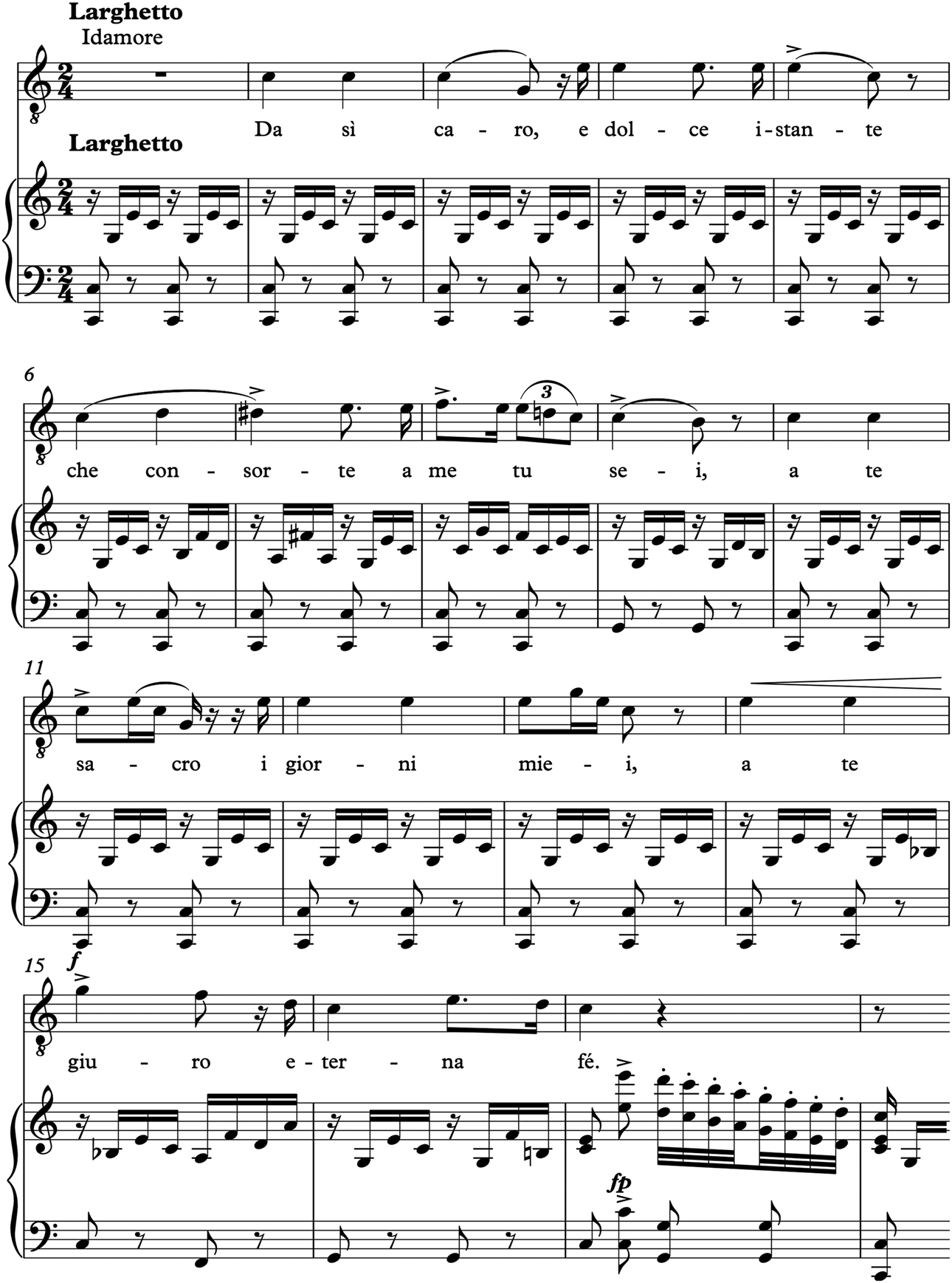

Whether it might be interpreted as diegetic music or as a shared verbal formula, the cabaletta in the love duet seems to fall among those cases of ‘suspension of the author's responsibility’, to use Zoppelli's words. Within the cabaletta, the composer's ‘voice’ gives way to Carlo and Linda's fictive voices, which – as we will see – rely on earlier musical materials. But are they also turning to a metafictive mode of expression? And, if so, what is the difference among the various occurrences of the theme? An examination of the piece in light of Donizetti's recourse to earlier melodic ideas can help answer these questions. The opening bars of the cabaletta theme can be found, almost identical, in a tragedia lirica Donizetti had written for the Teatro San Carlo ten years earlier, Sancia di Castiglia (1832).Footnote 37 In its original context, this piece was part of the opera's final scene, depicting the protagonist's hesitation between her protective instinct towards her son, Garzia – whom she believed to have lost his life in battle, but who has returned to Castile, thus becoming the legitimate heir to the throne – and her love for her second husband, Ircano, who plots to poison his rival for the crown, and convinces Sancia to help him carrying out this crime.

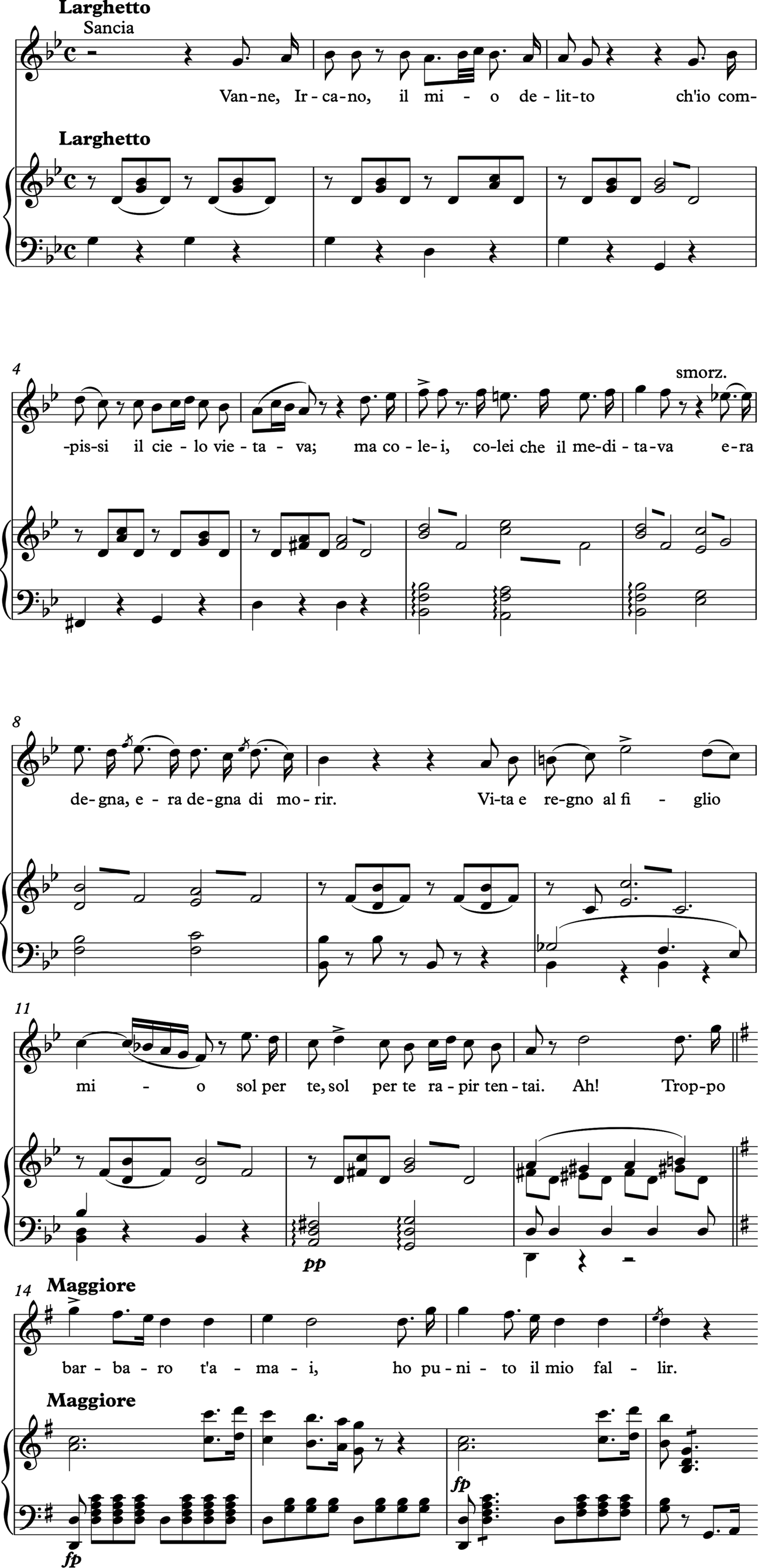

The opera's Finale has its roots in the model of the ‘gran scena’, which – in its standard layout – includes an opening scene introduced, or interposed, by a choral episode, a slow cavatina (here intended as a short aria in one tempo), and a transitional scene leading towards a double aria in four movements.Footnote 38 During the transitional scene, Sancia takes the golden cup from which Garzia is about to drink as part of the coronation rite, and has the poison herself, thus giving rise to the final aria, made up of a cantabile (‘Vanne, Ircano’), a tempo di mezzo (‘Traditore – Ardir contento’) and the closing cabaletta (‘Ah figlio mio non piangere’). The melodic line of the cantabile sets to music two quatrains of ottonari (see Table 2) and follows the structure of a lyric form a 4 a′ 4 b 4 c 4, (see Ex. 1) which starts in G minor and shifts to G major in the c section. The last two lines – corresponding to the c section – condense Sancia's dramatic gesture, at the same time indicating the cause of her guilt (‘Ah troppo barbaro t'amai’ (‘I loved you, too much a savage’)), and her ensuing self-punishment (‘ho punito il mio fallir’ (‘I have punished my wrongdoing’)). As Ashbrook has observed, a varied version of the melodic arch outlined in c resurfaces, in G major, in the cabaletta, where it anticipates the opening bars of ‘A consolarmi affrettisi’.Footnote 39 This cabaletta covers two stanzas of settenari (see Table 3), and its melodic line is constructed on a lyric form a 4 a′ 4 b 4 c 4 (see Ex. 2). At this point of the ‘gran scena’, Sancia has dispelled all doubt: whereas the first two lines (in E minor) refer to the present, starting with the third she foresees a reconciliation, when her soul could reach her son. Following an inexorable progression, in the third couple of lines Sancia begs Garzia to forget her guilt and, eventually, in the last couple of lines, advances a request to forgive her, thus offering peace to her soul. This last request (which refers to their imagined, future reconciliation) corresponds to the c section of the lyric form, where the melodic line shifts to G major (this time from the relative minor), recalling the melodic line of the c section in the cantabile. These two occurrences are linked by a cause-and-effect relationship: in the c section of the cantabile, Sancia underlines her act of atonement, thus setting the conditions to beg for Garzia's forgiveness in the corresponding point of the cabaletta's melodic line.

Ex. 1 Gaetano Donizetti, Sancia di Castiglia, Act 2, Ultima Scena, cantabile. Derived from the piano-vocal score n. 6706–6720 (Milan: Ricordi, 1832), and checked against Donizetti's autograph score. Bar numbers are an addition of the author

Ex. 2 Gaetano Donizetti, Sancia di Castiglia, Act 2, Ultima Scena, cabaletta. Derived from the piano-vocal score n. 6706–6720 (Milan: Ricordi, 1832), and checked against Donizetti's autograph score. Bar numbers are an addition of the author

Table 2 Gaetano Donizetti, Sancia di Castiglia, Act 2, Ultima Scena, cantabile (verbal text)

Table 3 Gaetano Donizetti, Sancia di Castiglia, Ultima Scena, cabaletta (verbal text)

Although the similarities with the love duet cabaletta from Linda di Chamounix are limited to just two bars, and while it is legitimate to wonder whether this is an aware case of self-borrowing or, rather, a recurring trope, a comparative reading with Sancia's cabaletta can offer new insights into the later opera as it has been examined so far. In Linda di Chamounix, Donizetti re-functionalized the pre-existing idea within a different structural frame, a 4 a 4′ b 4 a 4 coda4, whose a corresponds to the c section of Sancia's cabaletta (see Ex. 3). Whereas in the first opera the motif arrived at the end of a binary lyric form, as an unexpected relief switching to the major key, in the love duet it constitutes the main melodic material of a circular ternary lyric form. The strophe presents three repetitions: it is first exposed by Carlo, immediately repeated by Linda (with Carlo's brief interjections) and, after an interlude, it is sung by the two lovers joining a 2. The tension–relief dialectic of the original small binary form gives rise to an unproblematic, balanced structure, whose repetitions impress it in the audiences’ aural memory, thus allowing them to recognize it in the following scenes. When Carlo repeats it in the opera's Finale, the cabaletta theme in part recovers its original function. In the transitional section preceding it, during which Linda still refuses to recognize Carlo, his interventions are in G minor. Linda subsequently opens prospects for a resolution, in E-flat major, by prompting him to replicate the theme (‘un caro accento etc.’). As he gathers her tip, Carlo moves back to G minor one last time, before switching to G major for the reprise of ‘A consolarmi affrettisi’.Footnote 40 At a tonal level, the theme arrives as a relief, coming from its parallel minor; at a dramatic level, its function is to conclude Linda's agony.

Ex. 3 Gaetano Donizetti, Linda di Chamounix, Act 1, No. 3 Scena e Duetto di Linda e Carlo, cabaletta, bars 126–147. Derived from the Reduction for Voice and Piano Based on the Critical Edition of the Orchestral Score Edited by Gabriele Dotto (Milan: Universal Music Publishing Ricordi, 2008)

To sum up, the love duet cabaletta, which might be interpreted either as diegetic music or as a shared verbal formula, has its roots in a melodic gesture representing, in its original dramatic context, Sancia's hope for forgiveness. Forgiveness is a central theme in many of Donizetti's operas, oscillating between its Catholic overtones and human emotions.Footnote 41 Re-examining Carlo's final re-proposition of the cabaletta theme against the backdrop of its predecessor shifts the focus from its therapeutic to its twofold, redemptive function. As early as his romanza in the second act, before joining Linda, Carlo remarks that he is not a traitor, but to deserve her mercy and forgiveness: ‘Linda, non sono colpevole, / un traditor non sono: / ah! Ben di te più misero / pietà merto, perdono’ (‘Linda, I am not guilty, / I am no traitor: / ah! A great deal more wretched than you, / I deserve compassion and pardon’). When he joins her in Chamounix, before the closing denouement, Carlo explicitly asks her to forgive him: ‘È il tuo ben, che ancor t'adora, / che da te perdono implora, / uno sguardo, un tuo sorriso, / e felice tornerò’ (‘It is your beloved, who still adores you, / who implores your pardon, / one glance, one of your smiles, / and I shall be happy once more’). It is only by means of the theme's final reprise, implicitly restating his promise of marriage, that Carlo will eventually lead Linda not just to regain her mind, but also to forgive him. Though wrongfully, Linda has in turn been believed guilt by her father, representing the whole community. As Emanuele Senici has observed, the beginning of her madness coincides with the moment in which Antonio curses her.Footnote 42 By repeating their shared promise, Carlo exonerates Linda once and for all, thus sealing her innocence and redeeming her in the eyes of Heaven, of her father, and of the whole community (‘innanzi al cielo, agli uomini’). Coming back to the question on their modes of expression, we can conclude that, in the first act, Carlo makes a promise which – unlike Linda – he is aware he might not to be able to fulfil. Within the context of the cabaletta, he more or less consciously deceives Linda through a metafictive mode of expression, for which Donizetti relies on an earlier musical idea. By repeating the melodic line first presented by Carlo, Linda takes on a mode of expression which she believes to be genuine, remaining subjugated. It is only in the opera's final scene, when he re-enacts the theme, that Carlo's promise achieves validity, and his modes of expression become sincere.

Prayers and ‘Saintly Voices’

A predictable context for recycling existing materials is found in prayers, whose ontological status oscillates between diegetic music and verbal ritual. Prayers always involve not only the ‘abdication of the composer's voice’, but also the characters’ use of formulaic modes of expression, which encouraged Donizetti to transfer whole pieces from one score to the other on more than one occasion. A case in point is the prayer opening the Act 1 Introduzione from Maria de Rudenz, which later merged, in the same position, into La fille du régiment. The earlier ‘Laude all'eterno amor primiero’ (Andante, F major, 4/4) is unequivocally connotated as diegetic music, sung from inside a hermitage by a chorus of nuns over a strophic structure, and accompanied by the timbre of the organ. In the later opera, the prayer leaves its strictly religious setting to be recited by a chorus of Tyrolean women kneeling at the foot of a wooden statue of the Madonna, in search for protection from the advancing enemy. In its new, lay attire, the piece (‘Sainte Madonne’, Larghetto, F major, 4/4) maintains the earlier melodic line almost unaltered (though the strophic repetitions of the original are reduced), but it is supported only by the winds, marking its timbral edges.

A shift of setting and orchestral colour accompanies the journey of another – recurring – case of self-borrowing, which involves the protagonist's prayer in the closing number from Maria Stuarda (1834).Footnote 43 Maria's prayer, ‘Deh! Tu di un'umile’ (Andante comodo, 3/4, E-flat major), constitutes the slow section of her ‘gran scena’. William Ashbrook suggests that its melodic line in turn ‘derived from Il paria’,Footnote 44 but the question on whether this is a conscious derivation, or whether the two pieces at issue are based on the same, standard melodic trope, remains open. In the older score, the melodic idea appears in the instrumental interlude (Larghetto, 3/4, B-flat major) preceding Zarete's Act 2 aria, which depicts an ancient temple: it is based on the succession of two descending tetrachords covering an octave, the second of which ends on a diminished seventh chord on b-natural. The opening section of Maria's prayer follows a similar pattern, but the shared melodic gesture has a different functional weight on the structure of the two pieces. In the interlude from Il paria, it is the first half of the opening eight-bar phrase, which precedes the theme proper, and is heard only once. On the contrary, in Maria's prayer it covers the first four bars of the lyric form (A = a 4 a′ 4 b 4 c 4) around which the whole piece is constructed, articulated as follows: AA′B interlude A″A″′B′ coda. The final repetition of B – which is a shortened, varied version of A touching A-flat major – ends on the same diminished seventh chord on b-natural observed in the interlude from Il paria. It is tempting to read the rhythmic-melodic characterization of Maria's part, deviating from the flat layout of its presumed model, as an intentional allusion to the opening motif of the second section from the English anthem, ‘God save the Queen/King’ (1744[?]). In the anthem, two minor thirds are linked by a rising minor second, whereas in Maria Stuarda Donizetti links two falling fourths by a downward major second. Reinforced by Donizetti's actual quotation of the anthem in the overture he added to the score of Roberto Devereux (Naples, Teatro San Carlo, 1837) for the opera's Parisian premiere (1837), this hypothesis would provide the whole piece with a more explicit political dimension. The prayer implies a responsorial interaction with the chorus of Maria's households, arguably recognizing her as the legitimate heir to the English throne. In this light, the topical presence of the harp, whose arpeggios sustain the entire prayer, appears to allude here not merely to an otherworldly atmosphere, but also to Maria's Scottish origins.

The harp accompaniment disappears in both later uses of Maria's prayer, respectively in Le duc d'Albe and in Linda di Chamounix. In the latter, it becomes the ‘Gran Preghiera’ in which the Prefetto unites the villagers at the end of No. 5 Scena e Finale Atto primo, before the young Savoyards’ departure for Paris (‘O tu che regoli’, Religioso, 3/4, D major).Footnote 45 The outline of the new piece diverges from the earlier one in terms of structure and orchestral colour. Whereas in Maria Stuarda the prayer entails the repetition of the same melodic material, in Linda the theme is varied at each reprise, and is followed by a contrasting section presented by Antonio. The prayer's first exposition, sung by the Prefetto alone, is sustained by the strings in arpeggios. As the piece proceeds, the orchestral accompaniment is intensified by the progressive addition of woodwinds, brass and percussion, mirroring the gradual involvement of the whole community, and amplifying the role of the Prefetto as the village's spiritual guide.

In the second act of Le duc d'Albe, set in late-sixteenth-century Brussels, at the time of the Spanish domination, the prayer is deprived of its predominantly religious connotations to become a subversive hymn to Freedom (‘Liberté! … Liberté chérie!’, Larghetto, E major, 2/4). Sung by a group of conspirators, ‘tous à genoux’ (‘all kneeling’), as they arm themselves to attack their enemy, the piece preserves the responsorial structure of its predecessor. The first strophe is presented by Henri, the Duke's unwitting long-lost son, who is joined by the other conspirators in the subsequent repetitions. Similarly to Maria's prayer, the hymn's melodic line follows a lyric form (a 4 a′ 4 b 4 c 4) but, unlike the prayer, it presents a binary metre, 2/4. The change of metre involves a contraction of the melodic arch, which loses some of its repeated notes, to match the new, French prosody. In this version, Donizetti abandons the regular support of the arpeggios, which retrospectively seem to be a marker of religiousness. The novel, discontinuous accompaniment tends to emphasize the strophe's desinential sections, through the prevailing timbre of the winds, which provides the piece with an aura of solemnity. Two things should be noted here: on the one hand, moving from one work to the other, Donizetti not only re-adapts the piece, but also redresses it with a peculiar, orchestral colour depicting its dramatic context; on the other hand, he draws a timbral line delimiting the earlier piece, as well as the characters’ employment of formulaic modes of expression.

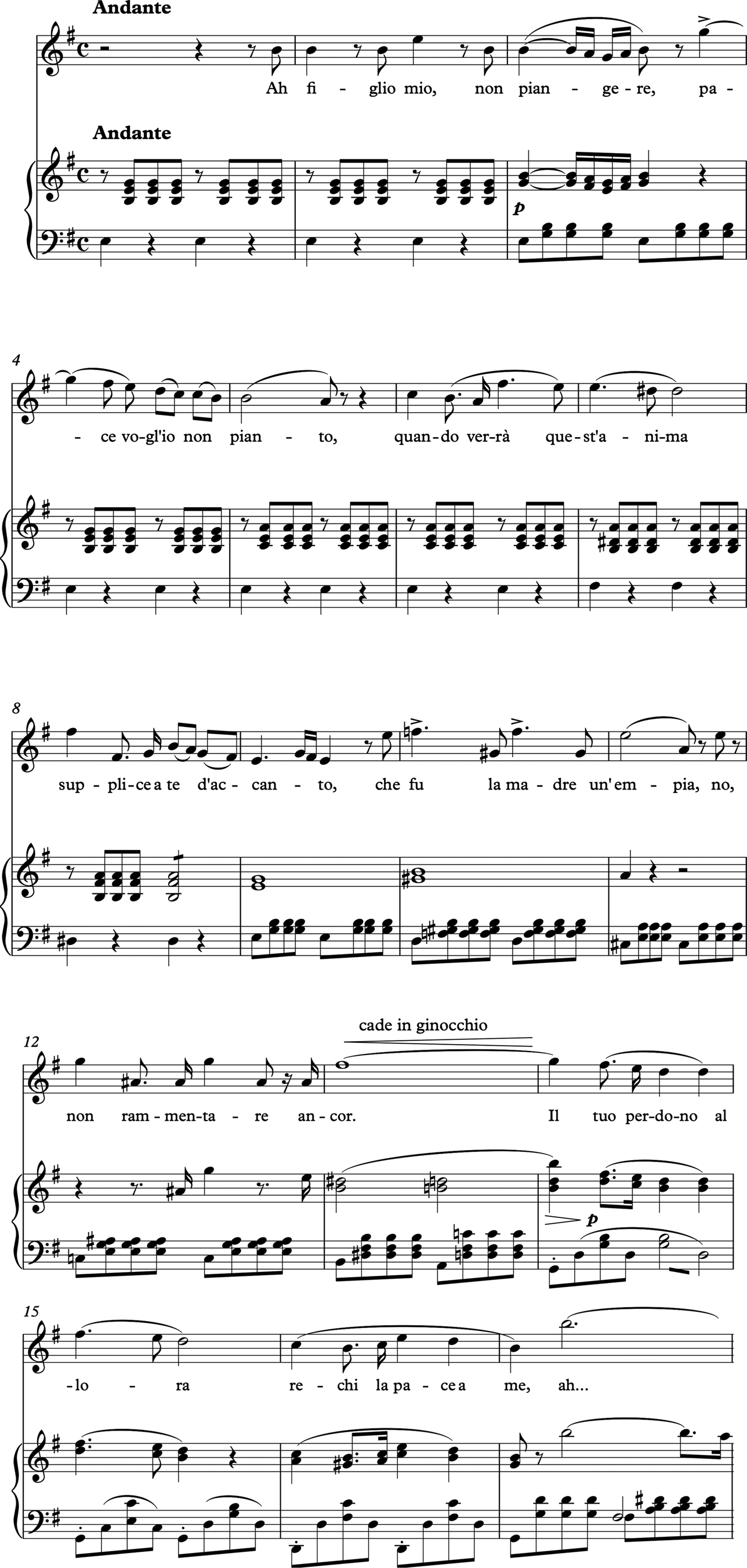

The migration of prayers across his scores – and across different confessions – might serve as a helpful context against which to examine Donizetti's re-use of the Larghetto from the Finale ultimo of Il paria in his first opera for Paris, Marino Faliero. Il paria is set in sixteenth-century India, where religious conflicts are intertwined with private life. Akebare, high priest and leader of the Brahmins, has granted his daughter's hand to Idamore, ignoring that the latter is the son of a ‘paria’. The final scene takes place in the Tempio di Brama, where Idamore and Neala are about to get married. The Larghetto (‘Da sì caro e dolce istante’, C major, 2/4) coincides with the wedding ritual, and it is constituted of two parallel strophes A (a8 a′8) A′ (a8 a′8), followed by an 11-bar coda: Idamore sings the first strophe alone (see Ex. 4), and is subsequently joined by Neala in the second. The strophes share the same verbal text, a quatrain of ottonari which appears to be a verbal wedding formula sealing the mutual vow (see Table 4). The melodic line remains in the area of the key signature, and is prevailingly diatonic, with only one chromatic passage in the first phrase, and a diminished seventh chord on the tonic in the second phrase, respectively underscoring the key words ‘consorte’ (‘spouse’) and ‘giuro’ (‘I promise’). The sonic space of the ritual is circumscribed by the presence of the harp, which first introduces and then accompanies the strophes with its arpeggios. Unlike other numbers of the score, where Donizetti experiments with exotic timbres, ‘Da sì caro e dolce istante’ portrays an ethereal atmosphere transcending the specific religion of the celebration, which dissolves as soon as Akebare's following sanction commences.

Ex. 4 Gaetano Donizetti, Il paria, Act 2, Finale, Larghetto. Derived from Donizetti's autograph score. Bar numbers are an addition of the author

Table 4 Gaetano Donizetti, Il paria, Act 2, Finale, Larghetto (verbal text)

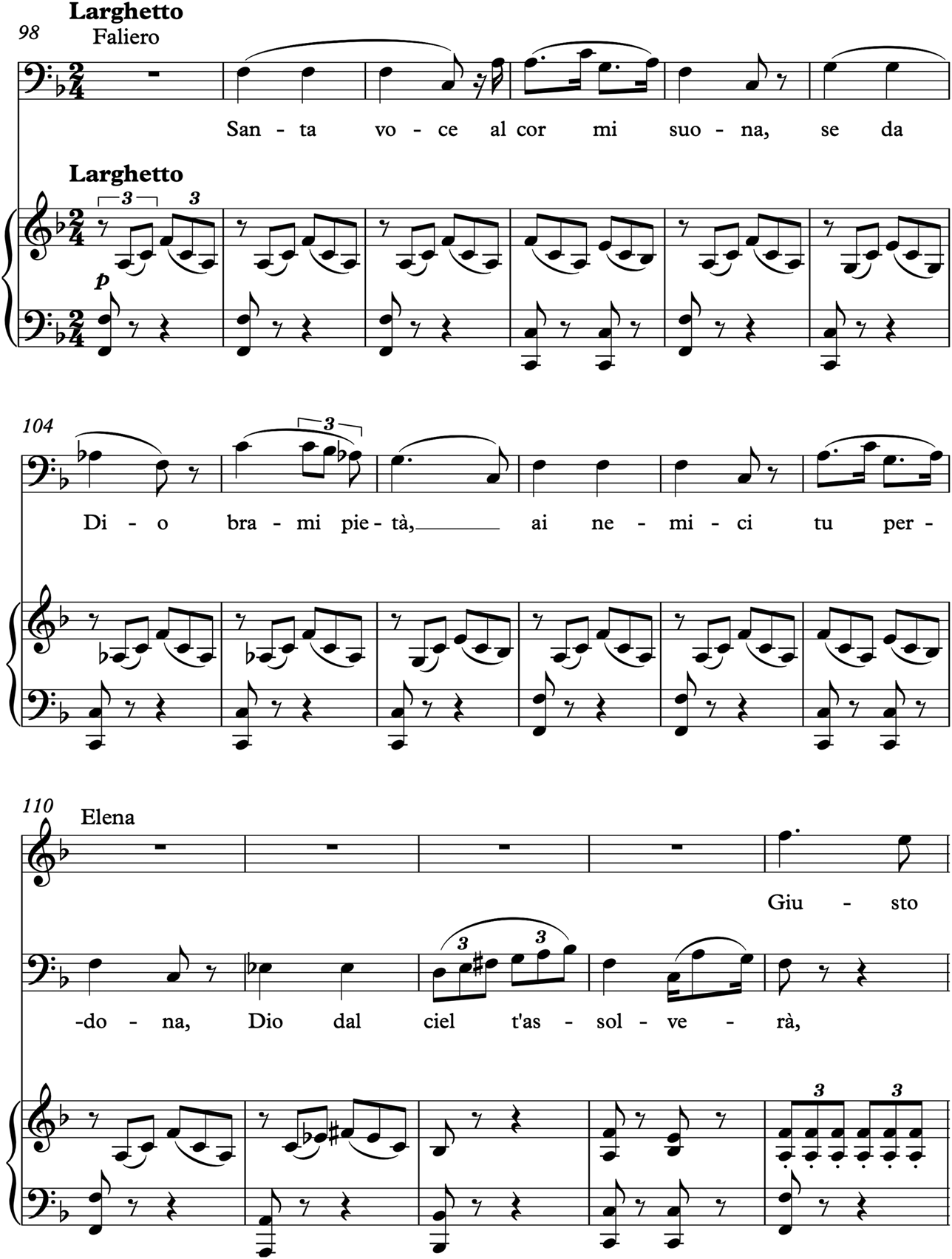

The absence of markedly exotic elements allowed Donizetti not only to place ‘Da sì caro e dolce istante’ at the centre of a parody satirizing contemporary Romantic trends, in La romanzesca e l'uomo nero,Footnote 46 but also to re-use it in his Torquato Tasso, set in late-sixteenth-century Ferrara, before adapting it to Marino Faliero. In both La romanzesca e l'uomo nero and Torquato Tasso, the theme accompanies a spontaneous expression of love. In the former case, it is sung by Antonia as the Andantino ‘Dopo tante e tante pene’ from her terzetto with Tommaso and Nicola. At this point of the terzetto, Antonia is still alone on stage with Nicola (whom she believes to be her beloved Filidoro), and she anticipates the joy of their imminent elopement and union.Footnote 47 In the latter case, the theme resurfaces in the first-act duet between Tasso and Eleonora, when the poet reads her the episode of Olindo and Sofronia, which she understands he wrote while thinking of their impossible love. At the words ‘lo sprezza’ (‘she scorns him’), Eleonora can no longer refrain from admitting her love to him on the melodic line deriving from Il paria, which is subsequently taken up by Tasso.Footnote 48 Thus, though losing its original ritual nature, in the cases just described the theme preserves its primary semantic function as an expression of love and amorous abandonment. The dramatic affinities with its source opera are less evident in Marino Faliero – set in mid-fourteenth-century Venice – where the theme can be heard in the cantabile of the closing duet between the protagonist and Elena, ‘Santa voce in cor mi suona’ (Larghetto, F major, 2/4). In the number's opening scene, Elena joins her husband in prison, where he is waiting to be executed, after the Council of Ten condemned him to death. Relieved to see her, Faliero expresses his desire to be buried with his nephew Fernando, who has just been killed by Steno. Faliero requests that both their faces be covered with a scarf he found on Fernando's corpse, which he does not know was a gift from Elena. At the sight of the scarf, Elena can no longer hide her secret, and confesses her adultery to Faliero in the duet's opening tempo. The following, frantic exchange is accompanied by a recurring syncopated motif in the strings, accelerating towards the moment in which Faliero is about to curse his wife. As if suddenly unable to complete his sentence, he suppresses his impulse and remains still, looking at the sky (‘Resta immoto! Guarda il Cielo’). After eight bars in which the strings in pizzicato and tremolo mark the passage to the following tempo, Faliero presents a varied version of the melodic line from Il paria, on the first of the three quatrains of ottonari constituting the cantabile (see Table 5). The melodic line is constructed around two parallel phrases in 2/4, F major (see Ex. 5). The only two transitional deviations from the key signature emblematically correspond here to the occurrences of the word ‘Dio’ (God): whereas in the first phrase the melodic line touches the minor parallel, in the second phrase it goes as far as G minor. Although Faliero's phrases – similarly to what was noted above for La romanzesca e l'uomo nero and Torquato Tasso – lose the ritual function of their original predecessor, they are equally delimited through a connotative orchestral colour, here embodied by the arpeggios of the strings, creating a suspensive effect. The arpeggios stop towards the end of Faliero's theme (bar 112) and disappear during the contrasting section introduced by Elena, only to resurface one last time at the end of the closing coda, when Faliero and Elena's parts re-unite on the words ‘Dio perdon’ (‘God, forgiveness’). In the following tempo, the recurring syncopated motif re-emerges, thus permanently closing the suspensive effect.

Ex. 5 Gaetano Donizetti, Marino Faliero, Act 3, No. 13 Scena e Duetto, cantabile, bars 98–114. Derived from the piano-vocal score based on the Revisione sui materiali autografi a cura di Maria Chiara Bertieri (Bergamo: Fondazione Teatro Donizetti, 2008, 2020)

Table 5 Gaetano Donizetti, Marino Faliero, Act 3, No. 13 Scena e Duetto, cantabile (verbal text)

In the case of Marino Faliero, Donizetti's self-borrowing falls outside the sphere of ritual pieces that imply a clear suspension of the author's narrative responsibility, as described by Zoppelli. His compositional strategies suggest, however, an implicit suspension of Faliero's ongoing modes of expression, for which Donizetti exploited a pre-existing piece that, in its original context, embodied not just a religious ritual, but an exchange of vows between the betrothed (the latter function being in part maintained even in its subsequent re-uses). Within the sonic space of his theme, Faliero appears to be guided by a Deus ex machina of sorts, to whom he can do nothing but surrender, and whose foreign modes of expression – the ‘saintly voice’ he hears in his heart – he makes his own, progressing towards a new emotional state and thus granting Elena his final forgiveness.Footnote 49

Reminiscences and Madness

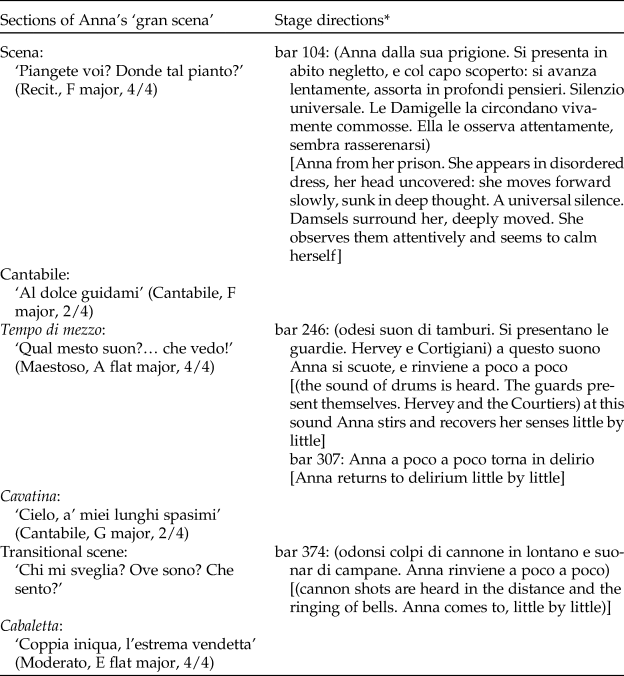

Donizetti's self-borrowing from Il paria to Marino Faliero allows for the investigation of a further case study, which shifts the discussion from diegetic music and rituals to the operatic representation of madness, implying a character's altered state of mind and – arguably – modes of expression.Footnote 50 I will focus, in particular, on the protagonist's mad scene at the end of Anna Bolena, which features ideas dating back to two different earlier works. The opera's final number re-elaborates the previously discussed structural model of the ‘gran scena’. For the second wife of Henry VIII, Donizetti reshaped its internal articulation in order to reach a macrostructure that could better fit the unfolding of the action. More specifically, he incorporated the cavatina in the final aria, which consequently appears to have two cantabili separated by a scene, before culminating – through a tempo di mezzo – in the closing cabaletta.Footnote 51 Even before Anna makes her entrance, the audience is forewarned of her delirium through the words of the chorus of her damsels (‘Chi può vederla a ciglio asciutto’), who have just left the prison where the Queen is incarcerated, and can now describe her continuous emotional swings. Donizetti would subsequently exploit the unusual succession of two slow tempos to emphasize Anna's repeated alternation from delirium to consciousness: she is delirious during her opening scene, and the following cantabile; she regains her mind as she hears the diegetic sound of the drums accompanying the entrance of Hervey and the guards, which mark the beginning of the tempo di mezzo; she reacts to Smeton's confession, towards the end of the tempo di mezzo, with a second phase of delirium, that will also embrace the cavatina; much like at the beginning of the tempo di mezzo, she is brought back to reality one last time as she hears the diegetic sound of cannons and bells announcing the marriage between Enrico and Giovanna (see Table 6).

Table 6 Structure of Anna Bolena's ‘gran scena’ at the end of Act 2, No. 11 Ultima Scena

* The stage directions reflect the layout of the opera's critical edition, where the portions of text derived from the printed libretto are in parentheses. See Gaetano Donizetti, Anna Bolena, ed. by Paolo Fabbri, Edizione critica delle opere di Gaetano Donizetti (Milan – Bergamo: Ricordi – Fondazione Donizetti, 2017).

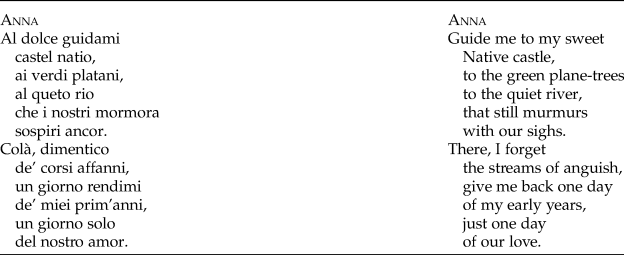

Anna's phases of delirium imply a perceptual shift towards the past, in opposition to the inexorable passing of time. During her opening scene (‘Piangete voi? Donde tal pianto?’), Anna re-lives the preparation of her marriage with Enrico. Here I would like to remark that, unlike most contemporary models, the scene presents no reminiscence motif, since the only recognizable melodic element is the second theme of the overture. Its transient apparition, in a major key, is interrupted when Anna fears that Percy could learn of her imminent wedding. She subsequently imagines that Percy has joined her and that, after initially blaming her, he is now willing to forgive her. In the following cantabile (‘Al dolce guidami’), Anna begs Percy to bring her back to her ‘castel natio’ (‘native castle’), where they had exchanged vows, so that she can re-live at least one day of their past love (see Table 7). The time shift is, therefore, twofold: whereas in the first part of the recitative Anna re-enacts her wedding with Enrico, when all her griefs originated, she subsequently strives to return to the place embodying the past of the re-enacted past. During the phase of delirium following Smeton's confession, through which she finds confirmation of her forthcoming death sentence, Anna revives her recent habits, recalling an episode from the opera's Introduzione. She asks Smeton to accompany her last prayer – which constitutes the cavatina of the ‘gran scena’ – with his harp, before her suffering can find relief in death.

Table 7 Gaetano Donizetti, Anna Bolena, Act 2, No. 11 Ultima Scena, cantabile (verbal text)

Writing in 1819, Artur Schopenhauer offered a philosophical account of madness within the wider context of its relationship with genius. Schopenhauer observed that mad people are not usually mistaken in their understanding of ‘what is immediately present’; rather, he explains,

their ravings always refer to what is absent or past, and only through these does it refer to its connection with the present. That is why their illness seems to me to affect the memory in particular; […] it has the effect of tearing apart the threads of memory, so that the continuous connections in the memory are abolished and a uniform or coherent recollection of the past becomes impossible.Footnote 52

Although Anna's memory seems to go around in circles, with no apparent linear continuity, she is perfectly able to discern present events and foresee their imminent effects. Not only does she come back to her senses twice, but in the first tempo di mezzo Anna is also aware of the psychic alteration she has just gone through (‘Oh! In quale istante / del mio delirio mi riscuoti, o cielo!’ (‘Oh! You shake me from my delirium at such a moment, o Heaven!’)). What is even more relevant to our discourse on self-borrowing is that Donizetti relies on pre-existing musical materials to depict both of her phases of delirium.

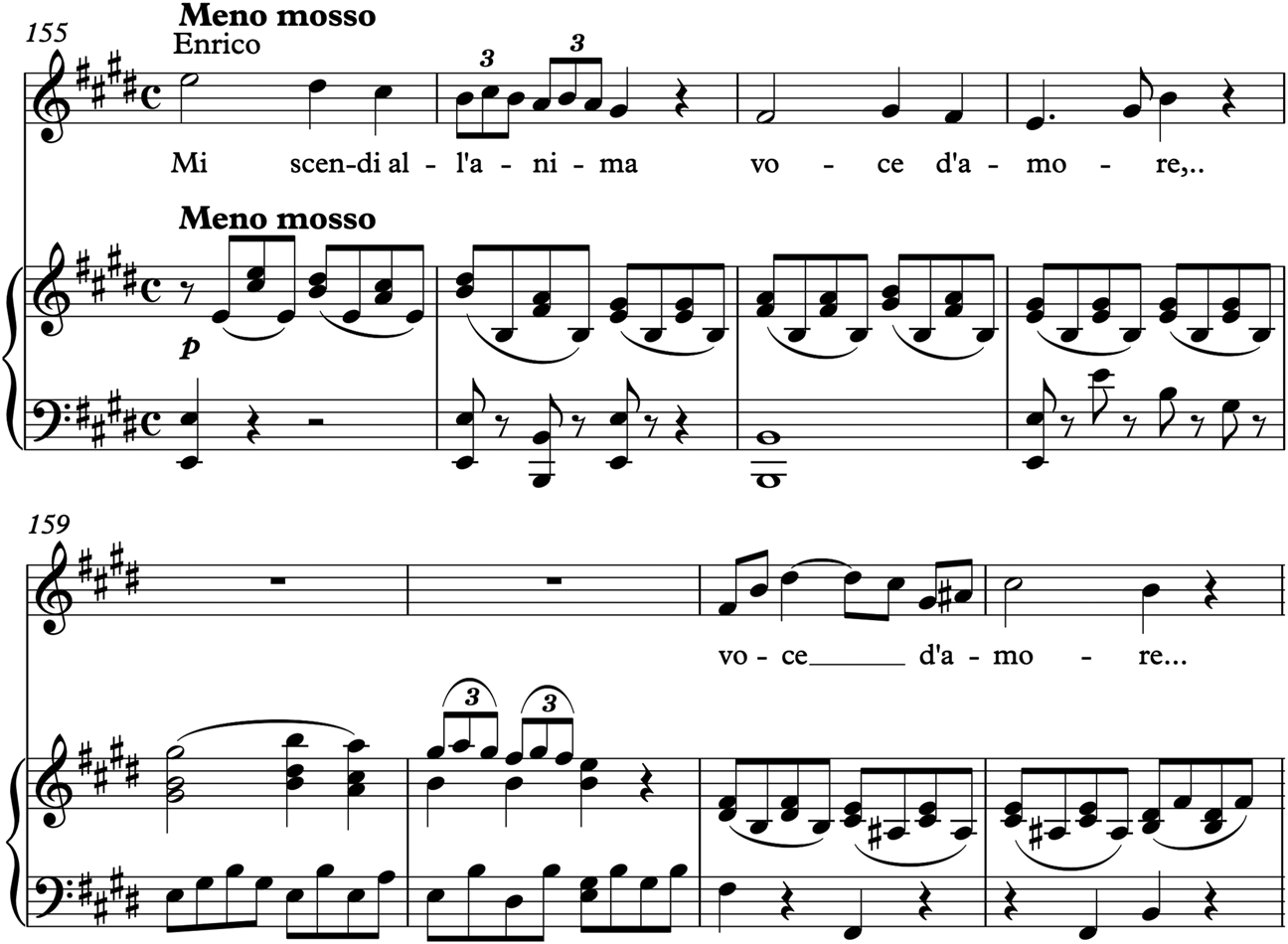

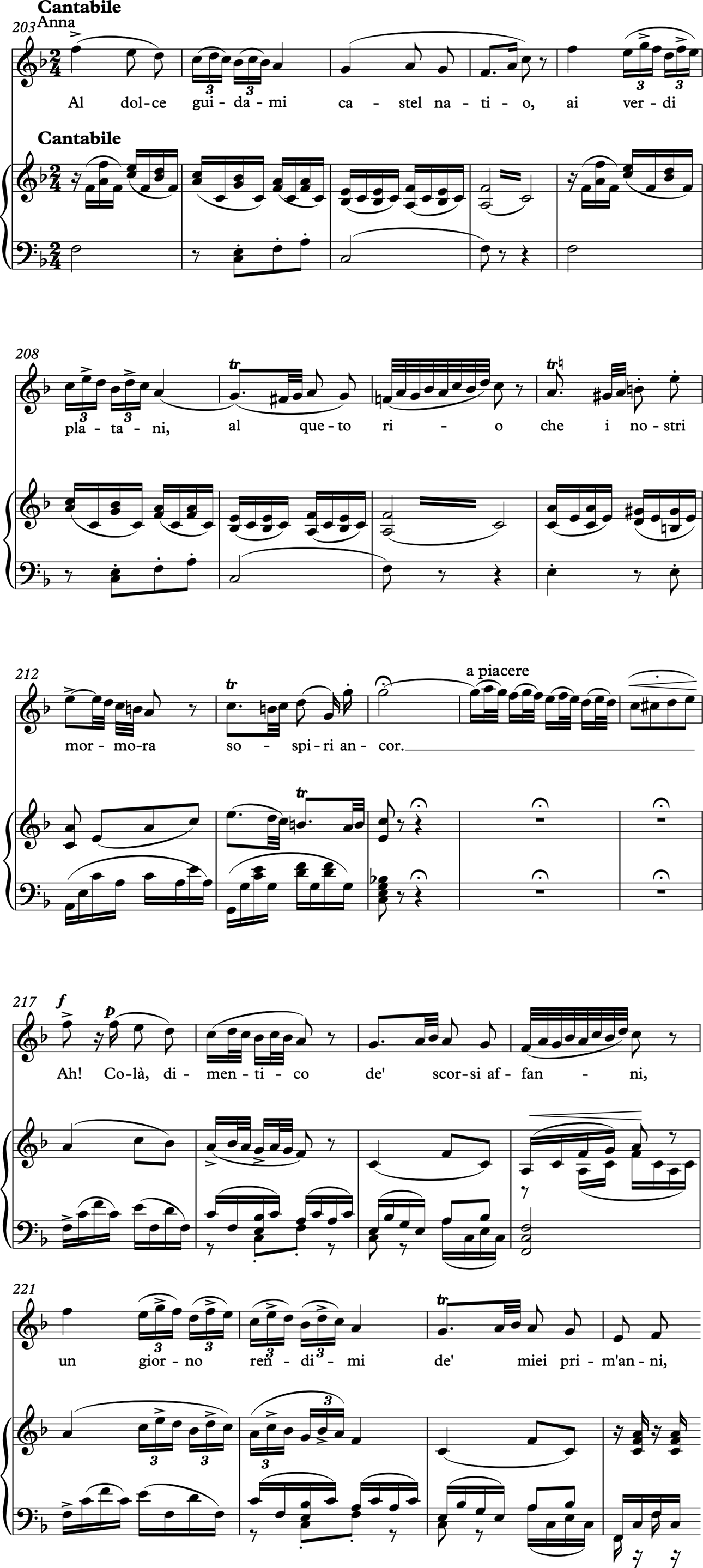

Anna's ‘Al dolce guidami’ re-elaborates the opening theme of the cabaletta from the protagonist's Act 1 cavatina in Enrico di Borgogna (Venice, Teatro San Luca, 1818). A melodramma per musica in two acts, the first opera Donizetti wrote as a professional moves from the pastoral atmosphere of the first scenes towards the heroic ambitions characterizing the second act. In his cavatina, Enrico (a contralto en travesti) is desperately searching for Elena, whom he ignores to have been promised to the son of the reign's usurper. Whereas in the slow section, ‘Care aurette che spiegate’, he addresses the natural elements to find Elena, in the closing cabaletta, ‘Mi scendi all'anima voce d'amore’, he foresees a resolution offering consolation to his heart. The cabaletta opens with an ethereal eight-bar phrase (a4 a′4) before proceeding in a purely Rossinian, virtuosic style which does not contemplate the reprise of the initial melodic figuration (see Ex. 6). It is the cabaletta's first phrase that re-emerges, almost identical in its melodic features, in Anna Bolena's mad scene. In the later opera, the pre-existing phrase is re-functionalized as the main melodic material (a) within a wider, balanced Liedform a4+4 b4+2 a′4+4 (see Ex. 7). It would be tempting to emphasize that, in its original context, this melodic gesture represents ‘a voice of love’ soothing the soul of Enrico, who – by the end of the opera – will discover he is the son of the defunct king of Borgogna, thus reclaiming his legitimate throne and his ‘native castle’. Donizetti's re-employment of the theme within Anna's mad scene must be read, however, against the number's second borrowing.

Ex. 6 Gaetano Donizetti, Enrico di Borgogna, Act 1, No. 2 Recitativo e Cavatina Enrico, bars 155–162. Derived from the Revisione e spartito canto/pianoforte a cura di Anders Wiklund, used at the Donizetti Opera Festival (Bergamo) in 2018

Ex. 7 Gaetano Donizetti, Anna Bolena, Act 2, No. 11 Ultima Scena, cantabile, bars 203–224. Derived from the Vocal Score Based on the Critical Edition of the Orchestral Score Edited by Paolo Fabbri (Milan: Casa Ricordi, 2017)

For Anna's prayer ‘Cielo, a’ miei lunghi spasimi’ (Cantabile, G major, 2/4), constituting her cavatina, Donizetti adapted a piece by a different composer, the then-renowned ballad Home Sweet Home by Sir Henry Rowley Bishop. After first appearing in his Who Wants a Wife? (1816), it subsequently resurfaced as a Sicilian Air within the volume National Airs edited by Sir Bishop in 1821. Bishop would finally recycle it in his operetta Clari, or the Maid of Milan (1823), with lyrics by John Howard Payne. In this new guise, the ballad became famous, spreading across Europe.Footnote 53 The operetta's subject revolves around the maiden Clari, who has come to Duke Vivaldi's palace with a promise of marriage that does not materialize. In her ballad, Clari expresses her nostalgic feelings towards her home – a different variation on the theme discussed above in relation to Anna's cantabile. The piece reappears as a reminiscence motif throughout the work, including a celebrated scene set at her father's household, in which it is played by a flute.

Although both Enrico's cavatina and Clari's ballad show more-or-less-nuanced dramatic affinities with Anna's mad scene – presumably reinforcing the condition for their re-employment – I would like to shift the focus onto a different aspect. The operatic representation of madness almost inevitably involves the use of reminiscence motifs, typically in the opening scene, and/or virtuosic vocal writing, which is usually confined to the closing cabaletta and contributes to the altered mode of expression.Footnote 54 Anna's mad scene presents no reminiscence motifs; additionally, her delirium finds room in the number's slow sections, rather than in the cabaletta: in the latter (‘Coppia iniqua, l'estrema vendetta’), she is perfectly conscious, which provides her final words of forgiveness with unparalleled dramatic power and authority. Donizetti's compositional strategies to represent both moments in which Anna is out of her senses, retracing her past, involve the use of pre-existing materials, deriving from musical-dramatic contexts that are foreign to the score. In the case of the prayer – in itself implying an abdication of the author's voice as well as the use of a foreign mode of expression – he resorted to a then-celebrated piece by a different author, originally serving the function of a reminiscence motif. Clari's ballad would have been easily recognized by the audience, bearing the potential to bring to mind its specific dramatic situation, and thus having a semantic value. In other words, within Anna's mad scene, (self-)borrowings take the place of the canonic reminiscence motifs, at the same time becoming the musical instrument through which to codify her altered modes of expression.

Conclusions

At the beginning of this article, I applied Beghelli's use of the term ‘self-preservation instinct’, which he identifies as the main cause behind Rossini's self-borrowings, also to Donizetti's way of recycling earlier materials, often deriving from works ostensibly destined to fall into oblivion. From this perspective, the practice of self-borrowing proves to be primarily economic, leading to a double benefit: saving time – within the context of a production system that left no room for hesitation – while capitalizing on pre-existing products. Donizetti would return to his musical archive in search of ideas or ready-made pieces (which he would always, however, re-adapt or re-compose to meet their new dramatic contexts) until the end of his career, when he had reached a prominent role in the European theatrical landscape. Pieces from L'Ange de Nisida – composed in 1839–40 for the Parisian Théâtre de la Renaissance, but unperformed for reasons beyond Donizetti's control – would re-emerge, for instance, not only in the score of La favorite (Paris, Académie Royale de Musique, 1840), which was its reworking, but also in Maria Padilla (Milan, Teatro alla Scala, 1841) and Don Pasquale.Footnote 55 Nevertheless, the examples discussed in this text call for a reassessment of the composer's aesthetic conception of self-borrowings.

The destination of most of Donizetti's self-borrowings consists in dramatic contexts implying the suspension of authorial narrative responsibility (as is the case with diegetic music and rituals), or what I have described as the suspension of a character's usual modes of expression. Donizetti's frequent reliance on pre-existing materials within these ontological boundaries (where they appear to be more legitimate) stresses their nature of foreignness to the ‘tinta’ of the work in which they would merge: reversing our perspective, Donizetti treats his own earlier music as a foreign product deriving from a different creative background. The result is the emergence of circumscribed ‘sonic islands’ – not too far from Dahlhaus's idea of diegetic music as ‘interpolated music’ – separated from the surrounding musical and dramatic context, and detached from the creative discourse inherent to the opera. Shifting to a different aspect of the same phenomenon, on several occasions Donizetti resorted to earlier pieces when revising his works and, more frequently, adapting them in view of specific productions.Footnote 56 This is certainly interlaced with the practice of replacing a certain piece of a given opera with another that could either better fit a specific singer's abilities or meet the audience's expectations. This latter practice, however, pertained to the performative sphere.Footnote 57 Whereas the ‘economic’ advantages of turning to his earlier works are obvious, here I would like to emphasize that, especially if the replacements depended on contingent requirements, adaptations fall outside the creative discourse of an opera, intended as an original, unitary work of art.

In some instances, Donizetti's self-borrowings are limited to a single melodic idea, which he would re-functionalize within a different structural frame. This has been observed, for example, for the final section of Sancia's cabaletta, which would later become the main melodic idea of the cabaletta from the love duet Linda–Carlo, or the motif from Enrico's cavatina, which would later resurface in Anna Bolena's mad scene. In these cases, the main reason behind Donizetti's recourse to prior materials seems to lie outside his wish to save time, becoming instead an instrument for a specific compositional strategy. In the same article on Rossini's self-borrowings from which I quoted earlier, Beghelli points out that

the transfer of his own themes that Rossini carries out from one score to another does not appear to have the aesthetic and semantically symbolic weight as what we would define a true self-quotation – such as, just to mention one example, the theme from Tristan and Isolde that Wagner includes in the third act of The Master-Singers with an intellectually allusive meaning.Footnote 58

The same does not seem to apply unconditionally to Donizetti's production. The ‘intellectually allusive meaning’ of a self-quotation requires it to be recognizable, which – except for his (self-)parodies – is not the case in Donizetti's works and would most likely be inopportune. Shifting the focus from the reception of a work to its creative process, however, Donizetti's dramaturgy appears to be animated by voices from his own artistic production that served a semantic function and bore a potential of intertextual allusiveness. In other words, Donizetti appears to adapt the economic practice of self-borrowing to an artistic means of organizing his dramaturgy.

When, in October 1960, Donizetti's first theatrical work, the scena lirica Il Pimmalione (1816), received its world premiere in Bergamo as part of the Teatro delle Novità, Marcello Ballini reported that the audience could grasp a motif anticipating Lucia's mad scene:

there even appears (and the audience's murmurs yesterday, at this point in the performance, were almost touching) an unbelievable anticipation of Lucia: precisely in the Air of Pigmalione, who feels he is becoming mad because his work does not yet show the result he seeks, this anticipation comes to light, almost identical to the celebrated Spargi d'amaro pianto … from Lucia's mad scene.Footnote 59

The inverted reminiscence of ‘Spargi d'amaro pianto’ (which, in the former work, consists only in an instrumental motif) led Ballini to read Pigmalione's frame of mind retrospectively, through the lens of Lucia's madness. At the end of our journey, it is rather tempting, however, to read ‘Spargi d'amaro pianto’ as yet another foreign – and meaningful – reminiscence through which to express Lucia's altered modes of expression, resonating within Donizetti's semantic soundscape.