Introduction

The Crystal Palace Brass Band contest of 1860 was held at an early stage in the development of an all-brass ensemble, being described by Roy Newsome as ‘a major landmark in the history of brass bands’.Footnote 1 The dimension that sets it apart from all previous brass band competitions is the scale of the event allied to the participation of bands from all regions of England and a contingent of brass bands from Wales. No previous competition had offered such an inclusive entry. Not only was the event a ground-breaking one in terms of representation, organization and location, it was acknowledged by contemporaries as ‘the greatest meeting of brass instrument performers which has ever been assembled’.Footnote 2

Since many participants playing in the bands had little formal education, there is a dearth of evidence to draw upon. Indeed, there is a paucity of primary sources to inform any history of the brass band movement in the early period of its development. The scarcity of sources means that it is necessary to rely on evidence from reports in contemporary newspapers and journals. The risks of this approach are acknowledged; indeed this article will expose some of the very problems associated with using newspaper accounts without critical appraisal.

Although the 1860 contest was widely reported by newspapers as a success, the competition only continued at the Crystal Palace for a further three years. Despite the attentions of several authors, no definitive reason has been established for the ending of the contests after such a short series. Several reasons have been postulated. First, the death of the General Manager, Robert Bowley, in 1864, may have led to a fracture in the relationship between the organizer, Enderby Jackson, and the Crystal Palace Company.Footnote 3 As will be discussed below, however, this is an error that emerges in secondary sources and is carried forward in subsequent studies.

Second, Cyril Bainbridge argued that the energies of the organizer, Enderby Jackson, were diverted in other directions; he became involved in other aspects of music theatre and large-scale events unconnected with brass bands from 1863 onwards.Footnote 4 It has been suggested that the opposition of the Board of Directors of the Crystal Palace Company to Jackson's proposed international brass and vocal competition between Britain and France caused him dissatisfaction.Footnote 5 Third, sources have pointed to the trend of declining entries, most sharply witnessed in the fourth and final event held in 1863, as a reason for the ending of the series. This decline in participation may have convinced the board that the event was not worth continued support.

These may have been factors in the discontinuance of the series of brass band contests, but this article will demonstrate that there were additional elements that are more significant in helping to explain its short existence. Furthermore, with reference to previously unexamined correspondence between Jackson and officials of the Crystal Palace Company, the article will challenge the presumption that the contests were ever a financial success in the first place, and will establish a conclusive reason for their demise.

Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was originally designed to house the Great Exhibition of 1851, which ran for six months until October 1851, attracting over six million visitors, an epic number commensurate with the scale of the building itself. The site chosen for the Great Exhibition was in Hyde Park, London, on which the proposed structure was intended to be built as a temporary feature. The Exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria, who delivered a speech to 30,000 guests assembled inside the structure designed by Joseph Paxton. A choir of 600 voices was accompanied by an organ and 200 instrumentalists directed by George Smart, by then aged seventy-five, although the musical arrangements were organized by the Sacred Harmonic Society and its conductor, Sir Michael Costa.Footnote 6 Paxton was determined that his design should not be lost, and he formed the Crystal Palace Company to oversee its continuance. At the conclusion of the Exhibition on 15 October 1851, the building was dismantled and eventually transported to a new site located at Sydenham to the south of London. The reconstruction of the building took two years, during which time it was considerably enlarged and improved. Part of the grand plans for the new building saw the construction of extensive terraced gardens and water fountains. The official opening of the new venue was attended by even greater musical forces than those of the Hyde Park grand opening. Sir Michael Costa was again engaged with the Sacred Harmonic Society, whose orchestra was augmented by professional players at a cost of approximately 150 pounds, and invitations were sent out for participants from provincial choral societies.Footnote 7 The bands of both the Coldstream and Grenadier Guards, together with about 60 brass players from the Crystal Palace Company resident band, were utilized. Costa had insisted that he be given access to music on ‘a very grand scale’ before agreeing to the invitation from the Crystal Palace Company to lead the opening ceremony,Footnote 8 asking for ‘200 instrumentalists, 1,000 chorist[er]s and two military and the Crystal Palace bands’.Footnote 9 The grand opening was again executed by the Queen, and 40,000 people were able attend the magnificent ceremony.

The Crystal Palace always operated on a gargantuan scale; indeed, as Michael Musgrave notes, ‘a cultural facility of such scope had never existed before’.Footnote 10 The Board of Directors Crystal Palace Company was the embodiment of the entrepreneurial spirit of the mid-Victorian era. Whilst Britain was proud of its imperial might and industrial power, the greatest developments made in this era was the infrastructure improvements in transport, communications, utilities and public services. The Crystal Palace is a case in point. The original building was conceived and built in a remarkably short period of time. The venue was only intended to be used for the Great Exhibition, after which it was destined to be demolished. The opportunity to develop the structure beyond its original purpose was seized by a group of investors. Because the Crystal Palace was not allowed to remain in situ, a plan to move the building was conceived and a private company was formed by Paxton to raise the capital necessary for the undertaking. Despite the challenges presented by relocation, the Crystal Palace was transported to Sydenham and redeveloped. A factor in the design of the site had been the connection to the rail network. A spur from the nearby London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway was built to connect the Crystal Palace to the national rail network. This gave access to the venue by visitors throughout the nation, not just the London region. The Directors of the Board recognized that a connection to the rail network was vital to the national role of the Palace that they sought to develop.

Several of the Directors were entrepreneurs who had been involved in transport speculations involving railways and shipping. The railways took the goods from inland manufacturers to the ports where they were sent from Britain to the emergent imperial markets, as well as importing raw materials from the Empire to the home market as two-way traffic. Just as the Crystal Palace was a visionary concept, so too was the idea of a national network of railways, requiring the skill set of entrepreneurially minded risk takers. The secretary to the company, George Grove (later Sir George Grove, originator of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, had himself served as a civil engineer engaged in railway construction in India.Footnote 11 The original Company chairman, Samuel Laing, had an extensive career in railway matters; in 1840 he held a position with the Rail Road Commissioners reporting to the Board of Trade. He later became chairman and managing director of the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway. Laing had early on recognized the opportunity to develop passenger trade instead of relying on freight. One of the original purchasers of the Crystal Palace was Leo Schuster, who was also a director of the same railway company as Laing. Other directors were involved in other aspects of entrepreneurial activities: Arthur Anderson for example was a shipowner and founded the company that later became the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, after having secured a government contract to deliver mail to India in 1839.Footnote 12 Some of the leading figures in the Crystal Palace Company were very wealthy: the chairman of the company at the time of the 1860 Brass Band Contest was Thomas Newhall Farquhar, who was descended from wealthy parentage. Others were of more lowly origins, such as Anderson, who was born on Shetland; his first employment was as a beach boy, before enlisting in the Royal Navy. Charles Geach, one of the original directors, was born in St Austall, Cornwall, and began his career as a clerk with a draper in that village. The original investors in the Crystal Palace Company had the foresight to envisage a future for the building and the necessary means and skills to ensure the proposal was completed. This action stands in favourable comparison to the vision for the more recent national project, the Millennium Dome – it took almost a decade to secure the future of that enterprise. The entrepreneurs of the mid-Victorian era recognized the potential of the building from the very beginning of its construction.

The Crystal Palace Company's connections with Enderby Jackson date back to 1859, when he was engaged to organize a handbell-ringing contest at the Crystal Place.Footnote 13 Jackson had been negotiating with the Company to host a brass band competition. The Company tested his abilities by arranging for him to bring 12 of the best handbell-ringing teams drawn from the north of England to compete at a contest at the Crystal Palace.Footnote 14 Presumably buoyed by the results of this initial experiment, the Crystal Palace Company agreed to Jackson staging a brass band competition at the Crystal Palace in 1860. By this year Jackson had organized many brass band contests in various locations throughout England, ranging from Darlington and Newcastle in the north, through Liverpool, Birmingham and Sheffield, to Lincoln and Norwich in the east and Bristol in the west.Footnote 15 It was apparent that these events had the capacity to draw enormous numbers of visitors attracted by the novelty of brass band music.

A feature of Jackson's contests was the inclusion of other attractions, such as horticultural shows, fireworks and gymnastic displays; but perhaps his main entrepreneurial skill lay in harnessing the power of publicity to ensure maximum interest in his events. A condition of entering many of his contests was the requirement for the competing bands to march to the railway station in their hometowns and then march to the venue from the destination railway station.Footnote 16 Jackson organized a brass band contest in collaboration with the Darlington Horticultural Show on 26 July 1858. This event was serviced by the provision of excursion trains from the surrounding towns and the crowd was estimated to be in the region of 20,000 spectators witnessing the contest.Footnote 17

Enderby Jackson as Brass Band Entrepreneur

Jackson was a central figure in the early years of the national development of the brass band movement, due to the standardizing effects of competition on a national level among participating ensembles. Jackson was therefore ideally placed to document the beginnings of the movement, and he produced a series of articles in later life entitled ‘Origin and Promotion of Brass Band Contests’. These articles were serialized in the Musical Opinion and Music Trade Review in 1896 and 1897. He discoursed on a wide variety of topics in these articles, ranging from instrument development to his recollections of the earliest brass band contests. The articles have been referenced extensively by authors engaged in charting the evolution of the brass band movement. They are not contemporaneous accounts but written many decades after the events that Jackson was describing.

Jackson also produced an autobiography describing his life and documenting his dealings with brass bands. This manuscript has never been published, existing only as a handwritten memoir. The location of the original manuscript is currently unknown, only photocopies are known to be in existence, one at Scarborough Library Archive, the Roy Newsome Brass Band Archive at the University of Salford, and the Enderby Jackson Archive held at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. The autobiography has also informed research in the same way that his articles have been used. The detail contained therein has been quoted without question, particularly regarding the series of brass band contests held at the Crystal Palace. In the absence of any other contemporary recollections, the manuscript has usually been taken at face value.

According to his autobiography Jackson was born in Mytongate, Kingston upon Hull, in 1827. His father was a tallow chandler and was himself descended from ancestors involved in that business. Jackson's mother died when he was young, and he does not appear to have enjoyed a close relationship with his father. He did work in the family business in his youth, but his writings make it clear he never intended to continue in his father's occupation.

Jackson was fortunate enough to have a grammar-school education, and he proved himself to be an adept student. He also took private music lessons and was able to play several instruments, as well as compose and harmonize music. Jackson claimed his love of music was inspired by hearing Louis Jullien's orchestra play at the Theatre Royal in Hull, where his father was responsible for the maintenance of the candles to illuminate the stage. The sight of Jullien's orchestra performing led Jackson to devote himself to his musical studies, to the chagrin of his father. Jackson decided he preferred music to being a ‘partner in Candle-making’.Footnote 18 Shortly after making this decision Jackson left his family and commenced work as a flute and cornet player on the York circuit. Jackson does not give a date for this fracture with his father, but he never refers to him again in his autobiography.

According to his autobiography, Jackson was engaged by the Doncaster Theatre for race week in 1853, and whilst chatting to a colleague was struck by the other's observation that prizes were awarded to horses and other animals to reward excellence, but this was never offered to musicians.Footnote 19 Musing on this thought, Jackson conceived the idea of promoting brass band competitions. In his autobiography Jackson states he circulated rules for a brass band contest to his principal friends, and the manager of the Belle Vue Gardens, John Jennison, seized his plan, which presumably resulted in the series of brass band contests at Belle Vue that began in 1853.Footnote 20

In due course Jackson organized a competition between brass bands at the Zoological Gardens, Hull, on 30 June 1856 in collaboration with a business partner, Robert Alderson. Also included in the fare for the day was ‘rural sports for juveniles’, with a pyrotechnic display to conclude the event.Footnote 21 The contest attracted a large entry of bands. Excursion trains were organized from East Riding, West and South Yorkshire, and Lincolnshire, bringing an estimated 14,000 visitors to the event. Receipts for the day totalled nearly 300 pounds.Footnote 22 The number of visitors attracted to the event gave Jackson the belief that brass band contests were a viable proposition, and he was soon promoting brass band contests in cities and major towns throughout England.

One of the factors behind the success of these contests was the negotiations with train companies for cheap excursion rates for the bands and supporters to travel to the venues. The expanding network of the train system gave opportunities for workers from densely populated areas of the country to travel to distant locations for leisure activities. The impact of railway excursions for the mobility of the lower classes is a little explored aspect of the development of the railway network. The railway excursion is generally defined as a return trip at reduced fares, either organized and promoted by a railway company or by a private organizer working in concert with the railway company, and restricted to a discrete group and/or offered to the general public.Footnote 23 Jackson was a private organizer, negotiating with railway companies to transport visitors to his brass band contest attractions. The best-known example of an excursion agent would be Thomas Cook, although this company aimed its prices towards the interests of the lower middle classes rather than the working class, generally selling first- or second-class tickets.Footnote 24

It would be difficult to compile a full list of all the competitions that Jackson organized since he was not always named specifically in the contest advertisements; but he was certainly very active in the eight years from 1855 to 1863. As stated above, Jackson's style of contest had hallmarks: they were often mounted in collaboration with other attractions, usually culminating in a massed performance of the competing bands and a fireworks display. The judges were often from a cohort of regular army bandmasters, with the dynastic figure of British military music in the Victorian era, Charles Godfrey (senior), a regular choice. Godfrey had begun his career as a drummer boy in a militia band before enlisting in the Coldstream Guards. He rose to become the bandmaster of this band and three of his sons became bandmasters in the British Army. His eldest son, Daniel Godfrey, was bandmaster of the Grenadier Guards Band. Daniel's son, also named Daniel, did not follow his father in a military career, but studied at the Royal College of Music, before he became the conductor of the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra.Footnote 25 In addition to their involvement in British Army music, the Godfreys arranged many of the orchestral pieces for brass bands that were used in the explosion of contests in the decades after 1860.

Jackson appears to have had a good working relationship with Godfrey as well as numbers of other leading military musicians who appear consistently as judges at his contests. In his autobiography, Jackson quotes from a note sent to him by Godfrey (senior) congratulating him on the success of the Crystal Palace contest in 1860, concluding with the following ‘The progress that music is making in the Provinces (more especially in the North) is extraordinary and reflects great credit on all concerned particularly yourself for the zeal and ability displayed by you on the late occasion’.Footnote 26

Jackson's writings reveal him to be a highly organized and determined man of many talents. He spent a great deal of time travelling around the country engaged in his business of promoting and organizing brass band contests. He set the blueprint for brass band competitions and was driven to succeed in his chosen line of work, having renounced a steady life and income when he left his family profession. He does appear to have had a strong sense of his own self-worth, claiming to have ‘imparted healthful moral excitement and musical zeal to the British workman’.Footnote 27 Whatever his motives, he was an impresario who made a mark on the life of the vernacular music experience of the Victorian lower class.

Robert Bowley and the Crystal Palace Company

In his autobiography, Jackson always refers to the general manager of the Crystal Palace, Robert Bowley, in warm terms, describing him as a ‘true and fast friend’.Footnote 28 What little that survives of the correspondence between Jackson and the Crystal Palace Company is usually signed by Bowley on behalf of the Company. Bowley is named in the newspaper accounts praising Jackson and presenting prizes at the Crystal Palace brass band contests. Jackson appears to have had a good relationship with Bowley during the years the contests were held at this venue and Bowley played a pivotal role in the negotiations between Jackson and the Company.

Despite Bowley's role in the organization of the Crystal Palace as general manager, surprisingly little of his life story has survived considering his status in this important venue. His biography has to be pieced together from census returns, commercial directories, and his obituary. Robert Bowley was born on 13 May 1813 in Charing Cross, London, where his father was a bootmaker. He continued in that line himself, appearing as ‘bootmaker’ in commercial directories as late as 1851, but he was also an enthusiastic amateur musician, joining the Benevolent Society of Musical Amateurs and later becoming its conductor. By the time of his marriage in 1834, he had already joined the Sacred Harmonic Society, and was to play an active part in this organization up until his death, both as a librarian and secretary. Bowley was responsible for the planning of the Handel festival that took place in 1857. This event became a triennial festival after the 1859 festival.Footnote 29 Presumably as a result of this success Bowley was appointed general manager of the Crystal Palace in 1858. In his study of music at the Crystal Palace, Musgrave asserts that Bowley was already the general manager by 1857 and was ideally placed to oversee this important initial festival, noting that Bowley was both ‘secretary of the Sacred Harmonic Society and the Manager of the Crystal Palace’ at the ‘Great Handel Festival’ held in 1857.Footnote 30 Whatever the exact dates involved, however, Bowley played an integral part in the establishment of the Handel Festivals held triennially after 1859, which were to assume an important role in the cultural life of the Crystal Palace.

Bowley was also an organist, having been being appointed organist of the Independent Orange Street Chapel, just south of Leicester Square, London in 1834. Bowley was therefore a musician, albeit an amateur, as well as a capable manager of the Crystal Palace. As we have seen he appears to have a good working relationship with Jackson, presenting prizes at the conclusion of the brass band competitions, and complimenting Jackson on the running of the contests.Footnote 31 Both Jackson and Bowley were born to parents in the ‘trading class’, and they shared similar talents: they were both musicians and natural organizers. Each left their family businesses behind to pursue their own career prospects, although Bowley's son, Kanzow Thomas Bowley, is listed in the 1861 census living with his father and family as a bootmaker, so it would seem he continued in the family business. As general manager of the Crystal Palace, Bowley liaised with Jackson and in his letter of introduction to Jackson, dated 23 May 1860, Bowley announced ‘I can confidently state that the success of this undertaking will be most unusual’.Footnote 32 The letter was sent to Jackson for him to use in his negotiations with the railway companies to bring the competing bands from their hometowns to London. The letter gives a clear indication that Bowley was confident of the success of the proposed competition, allowing Jackson an implied association with a venue beginning to promote high-quality musical events for mass audiences and participants.

How was Contest Series Judged a success?

The measurement of success is the central theme of this article, but success is a subjective term that varies depending on the perspective of the participant. The most important objective was to make a profit, increasingly necessary in these times of musical change from ‘patronage networks’ to ‘overtly driven modes of operation’.Footnote 33 The realization of profit was the ultimate aim of the Crystal Palace Company and always a concern of both the Board of DirectorsFootnote 34 and of the organizer, Enderby Jackson. It is therefore necessary to take a close view of the financial arrangements surrounding the contest series.

Financial Rewards

This exercise has never been undertaken on this series of contests before, but it is possible to establish with reasonable accuracy the amount of revenue achieved for each day. An examination of the surviving records indicates the viability of the events, whether a profit was made, and how it was ultimately distributed.

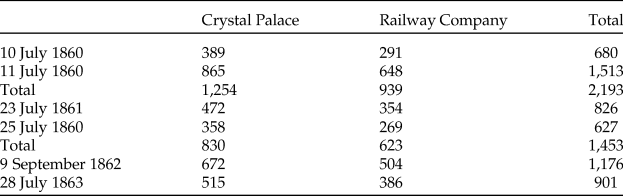

It is a simple matter to extract the visitor numbers from newspaper reports that were circulated on a daily basis; these were sometimes presented together with a cumulative figure of visitors to the Crystal Palace venue since its opening at the new site. Except for the first day in 1860, when admittance was half a crown (2 shillings and sixpence), all admission charges were one shilling for adults or sixpence for children under the age of 12.

The inaugural Crystal Palace Brass Band Contest was held over a two-day period, Tuesday and Wednesday 10 and 11 July 1860. The 1861 contest was held as a two-day contest in the same vein as the previous year, but two weeks later in the year than the 1860 event. Another difference was that the days did not run consecutively as in 1860, but were held on Tuesday and Thursday. It is not clear why the days were changed, although 10 July 1861 was booked as a Great Gala to celebrate Queen Victoria's birthday. On this date the tightrope artist Blondin was engaged and appeared before an audience of 37,347 visitors, 34,349 of whom were paying one shilling each for the privilege.Footnote 35 Blondin had been booked to appear on Wednesdays throughout July, and given his undoubted popularity, perhaps the band contest had to accommodate Blondin's act, so the contest days were changed to Tuesday and Thursday instead of consecutive days.

In contrast to the preceding contests, the 1862 contest took place on one day only, 9 September. The reason for the change of date was given in a report at an acrimonious meeting between the Crystal Palace Company directors and shareholders. The chairman stated the company had decided not to incur any great expense in booking special attractions due to the rivalling lure of the International Exhibition held in South Kensington. This new exhibition took place between May and September and the Crystal Palace Company was acutely aware this would impact on their own visitor figures.Footnote 36 For that reason the board had concentrated on repairing and improving aspects of the Crystal Palace, including the acoustics of the building with an eye to the upcoming Handel Festival. The visitor figures for the brass band event still represent a healthy, but not exceptional, attendance. The final contest was held on 28 July 1863, on one day as in the previous year.

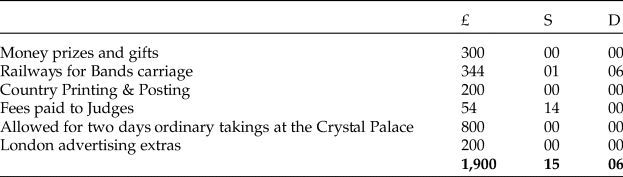

In consideration of the financial aspects of the brass band contests held at the Crystal Palace, it has been the practice of authors to rely on the figures presented by Jackson in his autobiography in which he details his expenditure.Footnote 37 Jackson refers to numbers from his cash book when compiling his autobiography in 1885 (see Table 1), stating that ‘After this money was realized by admissions, reserved seats, programmes, the Palace Company took two thirds, and I received as my total renumeration, the remaining one third over expenses’.Footnote 38 Programmes were charged at three pennies each and there were few, if any, reserved seats at the concert before the final.Footnote 39 If Jackson's figures are correct then the Crystal Palace brass band contest in 1860 would have had to generate more than £1,900 15s 6d before any profit was realized.

Table 1 Jackson's cashbook figures for the 1860 Crystal Palace Brass Band Contest

The original contract between Jackson and the Crystal Palace Company is held at the Scarborough Library Archive and details the terms to which the brass band contest held in 1860 was subject. The contract gives specific detail concerning financial aspects of the contract. The Company guaranteed Jackson £600 for expenses. The company also defrayed the cost of publicity in London as well as other places, together with all expenses at the Palace. The contract clarifies that season-ticket holders were to be admitted free. It goes on to state that the £600 expenses, cost of publicity in London together with other places, and a total of £800 (two day's ordinary takings) would be deducted from the balance of receipts, with the net amount divided two thirds to the Company and one third to Jackson. In the annotations in the contract it is noted that the £400 per day should be deducted as separate items and not as a cumulative £800. The inference being that any loss on an individual day should be borne by the company.Footnote 40 The visitor numbers are presented in Table 2. Season-ticket holders were admitted free, whereas all other attendees had to pay the admission rate.

Table 2 Visitor analysis: Crystal Palace Brass Band Contests 1860–1863

(a) Morning Advertiser, 11 July 1860, 5 (b) The Examiner, 14 July 1860, 12 (c) London Evening Standard, 24 July 1860, 6 (d) Morning Post, 26 July 1861, 7 (e) London Evening Standard, 10 September 1862, 3 (f) London Evening Standard, 29 July 1863, 3.

A further clause in the contract states that the Company had entered into an agreement with the Railway Company whereby the Crystal Palace Company would receive four sevenths of the ‘joint amount of admission and traffic receipts, the four sevenths coming to this Company shall be taken as the portion under this head[ing]’.Footnote 41 This arrangement had a net effect of reducing the revenue to the Crystal Palace Company and Jackson.

The cost of an excursion train ticket to the Crystal Palace was one shilling and sixpence; this covered the cost of both the train fare and admittance to the Crystal Palace.Footnote 42 This arrangement applied to all excursion trains to the Crystal Palace, not just the brass band contest. It is reasonable to assume that the season ticket holder would pay for the train as well, the cost being 6d. Due to the fact that the admittance price remained constant it is likely that the agreement between the Crystal Palace Company and the Railway Company remained in force for all the brass band contests for the four years 1860–63.

The revenue generated from admittance is shown in Table 3. To present the most favourable position of profitability, all visitors have been costed as adults. Season-ticket holders have had the excursion-train charge added to the total admittance receipts, presuming that all visitors travelled by excursion train (although undoubtedly some would have made alternative arrangements). It is obvious that the 1860 contest did not generate anywhere near the £1,900 15s 6d that Jackson details in his autobiography. The entire ‘two day's admittance’ would have raised a revenue of only £1,254, even before any deductions for costs and ‘ordinary day's takings’. There would of course be some adjustments for programmes and reserved seats, but these would not have significantly altered the total revenue raised.

Table 3 Financial analysis - Crystal Palace Brass Band Contests 1860–1863

There is no information relating to the agreement for the 1861 contest, but in 1862 the Secretary of the Crystal Palace Company, George Grove, sent a letter to Jackson outlining the terms for that year's contest. This shows that this contest was running on a much smaller scale than the first year. The arrangement of costs has changed for this year, with costs to both Jackson and the Crystal Palace Company being split equally for a total overall cost of £412 12s, representing £206 6s each.Footnote 43

A key element of this agreement is that it is stipulated that the contest must consist of not less than 20 bands. Again, the receipts were to be divided – two thirds to the Company, one third to Jackson. There is no reference to any adjustment for a ‘ordinary daily receipts’ as in the 1860 contest; nor is there any reference to an arrangement with railway companies as in the original contract. There is no reason to suppose that the arrangement with the railway company would be any different to that of 1860, given that it is an agreement for all excursion trains to the Crystal Palace, not just for the brass band contest.

It can therefore be seen that the overall revenue raised by admittance fell year on year, and it is evident that the profit would not have been sufficient to sustain the interest of the Crystal Palace Company or to be a lucrative reward for the exertions of the redoubtable Jackson.

Reception

A further measure of success is the resultant publicity generated by the events. The newspaper coverage of the contest was circulated throughout Great Britain and is an important factor in the growth of both the brass band medium and the contest series, as well as the inspiration for other rival attractions, as will be demonstrated. Although the press coverage does not constitute a financial reward, it is still a reward of sorts to the sponsoring organization, the Crystal Palace Company, and the organizer, Jackson. The Crystal Palace would be hosting great events from all parts of the country organized by the Volunteer movement and the various national movements, Oddfellows, Temperance Societies, Choral groups, and so on. These newspaper reports are a barometer of the contest's success, since they give impressions of the atmosphere and the overall organization involved. They attest to the smooth running of a contest that involved many participants and would have established the credentials of the Crystal Palace, and they identify those responsible for dealing with such a complex event. Caution is needed, because some of the reports were worded in a standard fashion and one can detect the hand of Jackson in the wording of the coverage. In any case, the media reception did give an impression of a national venue capable of coping with huge numbers of visitors, and it helped the Crystal Palace Company in projecting itself into the national consciousness.

The two-day event in 1860 generated publicity on a national scale, being reported extensively throughout England and Wales. The contest attracted a large number of visitors over the course of both days. There is no doubt that this contest represented a triumph of organization; no brass band contest had been arranged on such a scale prior to this event. In terms of logistics this competition must surely be viewed as having been a success. This inaugural event was widely acclaimed as such, The Times, reporting ‘For a first experiment of this kind the success was quite extraordinary’.Footnote 44 In his autobiography, Jackson records he was congratulated by Charles Godrey (senior) on the second day. The music critic of The Times, J.W. Davidson then ‘honoured him by eulogising on his spirited conducting’. And finally, Bowley publicly tendered his thanks on behalf of the Crystal Palace Company.Footnote 45 These proceedings were covered extensively by London newspapers, and summaries of the contests, together with an account of the concert and award presentation ceremony, were circulated throughout the country. Not all accounts were universal in their praise: the Morning Chronicle made reference to an inordinate delay waiting for the judge's decisions, noting that ‘The proceedings might have gone more smoothly certainly; nevertheless, taking all things into account, we must pronounce the monster meeting of the Brass Bands a success’.Footnote 46

Newspaper reports on the 1861 contest were, on the whole, muted in their response to the events over the two days. There was some interest in the prize for the best bass on Thursday, which was won by Mr. Midgely from the Keighley Band, playing a double B-flat trombone ‘of his own invention’.Footnote 47 There were no eulogies featured, unlike the previous year. A somewhat sour note was injected by The Era, which stated that ‘The list of competitors was very long, and the time occupied in getting through the various programmes was very tedious’.Footnote 48 This contrasts vividly with the report of the 1860 contest from the same newspaper, which declared ‘The performance of Tuesday and Wednesday will long live in the memory of all who were present, thanks to Mr. Enderby Jackson, who has proved a perfect Napoleon in the organisation and marshalling of large masses of musicians’.Footnote 49 Overall the majority of the detailed reports were carried by provincial newspapers; for some reason this particular contest did not attract much interest amongst the London publications.

In 1862 the contest was given detailed coverage by several of the London newspapers, and the tone was generally more complimentary than that offered in 1861. The most praise was given to the efforts of the combined bands in the customary concert before the winning announcements: ‘the effect on the multitude was particularly striking, and the whole can only be summed up in one word – Sublime’.Footnote 50

The coverage of the contest held in 1863 was muted, with no major London publication giving any account apart from The Era and The Sun. Even these accounts were functional, containing the details of bands attending and results. There was an absence of congratulatory comments as in previous years. The most extensive accounts appeared in provincial publications where local bands had won a prize (a very detailed account appeared of the exploits of the Blandford Band winning first prize together with the celebrations of the Blandford town populace on the band's return to Blandford).Footnote 51

Band participation

The last factor to consider is the level of band participation in the contest, which proves the most difficult element to establish. As will be demonstrated, Jackson usually advertised inflated estimates of the number of brass bands appearing in the contest. The number of participating bands would vary in advertisements leading up to the contest, then the published programme on the day contained fewer bands than had been claimed. The final complicating issue is that some bands simply did not appear on the day of the contest. It is not always possible to establish precisely how many bands did compete, since all the bands were split between the platforms distributed throughout the grounds of the Crystal Palace during the initial rounds. However, there are clues that help give an understanding of the number of actual participants.

Bands attending

The advertisements for the 1860 contest gave varied numbers of bands expected to attend, ranging from 99 to 115.Footnote 52 Bell's Life and Sporting Chronicle provides a comprehensive list of 72 bands for the event on Tuesday 10 July and 98 bands for the Wednesday 11 July contest.Footnote 53 The list contains details of conductors and leaders of the respective bands. Due to the dislocation of performance sites referred to above, it is unlikely that any person apart from the organizer would know the exact number of bands attending the contests.

The newspaper accounts for the 1860 contest state that 44 bands attended on Tuesday 10 July, and 52 on the second day, Wednesday 11 July. Many of the bands attending on the first day also played on the second day, so considerably fewer than the 100 advertised, doubtless having been placed to attract visitors, would have appeared over the two days. Listeners were free to wander as they pleased to enjoy the grounds, but a focal point was the concert held before the finals when all bands were expected to muster in the Crystal Palace. The combined bands then played several pieces whilst the judges made their decisions, selecting two bands from each of the platforms to perform in the final.Footnote 54 The concert and final performances were attended by thousands of visitors.

Evidence of reduced expectations in terms of the number of bands anticipated for the 1860 contest can be found in advertisements dated as late as 7 July. These advertisements for the contest also contained instructions for the band leaders to gather at Exeter Hall on the evening of Monday 9 July 1860. The instructions detail that bands competing were to be distributed in the Crystal Palace grounds on eight platforms.Footnote 55 This announcement was changed on 9 July when the number of platforms was reduced to six.Footnote 56

All bands were expected to play twice: the first piece was the nominated test piece, ‘the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel's Messiah’, and then a piece of the band's own choosing. A remarks sheet held at the Roy Newsome Brass Band Archive at the University of Salford details the bands competing on platform 4 in the second round on Tuesday 10 July 1860. The sheet names each band in order of appearance, but ‘the band playing sixth’ is missing. This should have been the Blandford Band and it is highly likely that they did not play. They also appear on the programme for Wednesday, but given their absence on Tuesday, it is unlikely that they were in attendance. And in 1861 Blandford are reported playing for a demonstration by the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows at Weymouth on Monday 23 July 1861, the night before they were due to play at the Crystal Palace,Footnote 57 which makes it unlikely that they played in London the next day. In 1862 and 1863 Blandford began attracting coverage from local newspapers, particularly in 1863 when the band won the contest. It is therefore highly likely that 1862 was in fact the first year the Blandford Brass Band appeared at the Crystal Palace contest, despite their inclusion in the list of bands entered in the earlier years.

On the day of the second contest newspapers were proclaiming that 115 bands were to compete on Wednesday 11 July 1860,Footnote 58 whereas in its report on the day's events the Morning Chronicle stated that there were 72 bands at the contest.Footnote 59 There were actually 52 bands listed in the programme, but it is certain that fewer than 52 bands played in the contest. The programme shows both the Compstall Band from Cheshire and the Wednesbury Band are duplicated: appearing twice in the same programme on different platforms.Footnote 60 The Blandford Band are shown as entered on platform 4 but it is likely they did not play for the reasons given above. A further brass band, the Witney Amateurs are listed as playing on platform number 6. According to the programme they had elected to play as their own choice a Grand Selection from Lucretia Borgia by Donizetti. This band had played on the first day of the contest, Tuesday 10 July 1860 when one of the players present, William Smith, had performed with that band.

William Smith was a blanket manufacturer who penned his memoirs in 1872, describing playing with the Witney Amateurs at the Crystal Palace contest on the Tuesday. Smith gives a detailed account of his experience at the Crystal Palace contest in 1860, and, although there are some inaccuracies in his memoirs, his account is a crucial piece of evidence of the events of the contest. The band had chosen to play a Selection from Verdi's Il Trovatore for their own-choice piece; this had been arranged as a solo for one of their bass players to play with the band accompanying the player. This choice was made because there was a prize for the best bass in the contest. Witney went through to the final on Tuesday, expecting to have to play the test piece, the Hallelujah Chorus, but Jackson demanded that the final competition piece should be from an operatic selection. This came as a surprise to the Witney Band, as well as other bands. The Witney Band did not have any other music and were forced to play the bass solo arrangement from Il Trovatore again. This obviously limited the appeal to the judges and the band did not feature in the prize list. Smith only mentions playing on the Tuesday and also makes it clear that they did not have any other piece of music with them, certainly not the Grand Selection from Lucretia Borgia by Donizetti that was listed in the programme.Footnote 61

It is significant that the Witney Band were listed playing a piece they evidently did not have, and it is highly unlikely that they would have participated in the Wednesday competition. The Saltaire Band had been disqualified from playing on the Wednesday contest by virtue of winning second prize on the Tuesday contest. This therefore means that at least three bands, Saltaire, Witney and Blandford, did not play on Wednesday. There were two duplicated bands, Compstall and Wednesbury, which further reduced the total. There were at most 48 bands present on Wednesday 11 July 1860. The likelihood is that even more bands were absent from the programme.

In 1861, detailed lists of bands attending were featured in advertisements, when 41 bands were listed for Tuesday 23 July.Footnote 62 However, some advertisements still contained vague figures of ‘upwards of one hundred bands, from all parts of England’.Footnote 63 Jackson must have been aware that a much reduced number of bands were competing since the published programme for Tuesday 23 July only contained the names of 19 bands playing instead of the 41 listed the previous day in newspapers.Footnote 64 Out of the 19 bands listed as performing on the Tuesday, only 17 played, representing less than half of the original entry as published in newspapers.Footnote 65

The contest held on Thursday 25 July 1861 had 54 bands listed as competing in the London Evening Standard, but in the event only 20 bands attended.Footnote 66 This represents an even greater proportion of absentees than on the first day. An analysis of the bands listed as playing in the programme show a combined total of 27 individual bands, much less than the vague figure of over one hundred claimed in the pre-contest advertisements.

In 1862 the contest was advertised throughout England, although most of the advertisements consisted of details of excursion trains travelling to the contest. Shortly before the contest, a list of 49 bands was published.Footnote 67 Twenty-six bands actually attended the contest.Footnote 68 It is of note that the larger proportion of bands entered were from the midlands and southern regions. There were seven bands entered from the Yorkshire area, with no representative from Lancashire.

The following year, 1863, saw several advertisements in the metropolitan newspapers containing all bands listed as attending.Footnote 69 All the lists are identical, and they name 46 bands. As if to reinforce the message that a large number of bands would attend, the London Evening Standard carried a report that ‘upwards of thirty of the bands arrived from various parts of England yesterday’.Footnote 70

Reports of the 1863 contest were widely circulated in newspapers throughout England and all reports state that bands played on three platforms in the grounds of the Palace, seven bands per platform. At the conclusion of the preliminary round, 12 finalists were selected from the entry, presumably four from each platform.

All reports carried by newspapers agree that 21 bands attended the 1863 contest. Two surviving remarks sheets for this contest, held at the Roy Newsome Brass Band Archive, detail the bands performing on platforms one and three. There are no remarks available for Platform Two. The remarks for platform one list five bands, four of which are named in order of merit: Blandford, Brighton, Leyburn and Albion Heckmondwyke. The fifth band is not named. The remarks for platform three list four bands, all of which are again named in order of merit: Dewsbury Band, Matlock Band, Doncaster and Kirkburton Band.

The remarks sheets usually contain details of all the bands competing. The one surviving remarks sheet from the 1860 contest gives a brief summary of each band performing, and this sheet has one band missing in numbered order, indicating that one band (Blandford, as detailed above) did not attend.Footnote 71 It is reasonable to assume that the nine bands listed on platforms one and three in 1863 were the only ones playing on these two platforms. If 21 bands attended in 1863 it would be disproportionate to have the remaining 13 playing on platform two; this would affect the performance timings for the whole contest. It is therefore most unlikely that 21 bands played at this contest, contrary to all the publicity published after the event. It is reasonable to assume that either four or five bands played on platform two, meaning a maximum of 14 bands attended the contest and performed in the initial rounds.

Jackson and Bowley

In his memoirs Jackson states that in 1864 he became involved with theatrical and music hall speculations to such an extent that these responsibilities ‘precluded me from giving the time to the Palace Contest’. As a result of this decision, he goes on to say Mr Bowley promised ‘the contest would not be entrusted to any other person so long as he lived, a promise he honestly carried out’.Footnote 72 Jackson also states that he had given five continuous years to the Crystal Palace Company, all of which were successful financially, ‘which was well known to Sir George Grove … his musical services being limited to writing out programmes etc. from copy supplied’. Reading the Jackson autobiography, therefore, one is left with the impression that Jackson simply lost interest in staging a brass band contest at the Crystal Palace.

Death of Bowley

Several authors have contended that Bowley died in 1864 and this was a further contributing factor in the discontinuance of the Crystal Palace brass band contests. However, Bowley did not die in 1864, but remained in post as the general manager of the Crystal Palace until 1870. In 1870 Bowley had been suffering from ill health for several months and was urged by his physician to leave his work for a period of recuperation at the seaside. Bowley had steadfastly refused to take the advice, until arrangements had been made for him to go Scotland via Birmingham, accompanied by a friend. On Wednesday 24 August Bowley left his home, telling his wife that he was going to the Crystal Palace to pick up some papers that he intended taking with him to Birmingham on Sunday. He travelled into London and took a journey on the steamer ‘Ceres’ on the River Thames. Whilst the boat was travelling in the centre of the river, Bowley deliberately jumped from the boat, and although he was recovered promptly, he died from drowning. Several letters were found on his person indicating that he was suffering from fatigue, one extract reading “I feel so weak, so worn out, I can do nothing … It is so hard, as head, hand, and energy are all gone”. The inquest, held at Admiral Hardy Tavern, Greenwich on Friday 26 August returned a verdict ‘That the deceased committed suicide while labouring under temporary derangement’.Footnote 73 Whatever the reason for the discontinuance of the brass band contests at the Crystal Palace, it was not the death of Bowley.

Correspondence ending the Competition

New light on this vexed issue, however, can be shed with reference to a letter that has come to light in the Roy Newsome Brass band Archive at the University of Salford. The letter is written by Bowley to Jackson.

April 7 1864

Dear Sir,

I have submitted our correspondence to a Committee of the Directors who have undertaken to advise on the specialities of the coming season. The result of their deliberations is, that from the experience derived from the visit of the Orphionistes and the cost connected therewith,Footnote 74 it is not likely that the addition of vocal music to a Brass Band Contest would be of service.

With respect to the proposed International Brass Band Contest, they would only concur in its being carried out at a moderate expense and at a moderate outlay.

It would be requisite if I am to bring it under their notice again, that you should inform me precisely of the cost which would be entailed upon the company, as well as the number of English and French Bands which it is understood would compete.

I may add that Brass Band Contests with us, as you are doubtless aware, have failed in realizing any considerable results. The only new features would be the concurrence of the foreign bands.

If therefore you will give me at your earliest convenience, a detailed estimate of the cost to be incurred by the company, I will again place it before our committee and let you know the result immediately.

Dear Sir,

Very truly yours,

Rob Bowley.Footnote 75

The key consideration in commissioning the contests was that of financial return for the Crystal Palace Company; it is clear from the letter from Bowley to Jackson that the venture bringing brass bands to the Crystal Palace had ‘failed to realize any considerable results’. There was no reference to Jackson staging a brass band competition at the venue in 1864 other than his proposed International Contest between France and England. However, this proposed international contest was viewed in an unfavourable light due to the costs that had been incurred when L'Orpheonistes had visited the Crystal Palace in 1860. In his autobiography Jackson writes that his proposed International Meeting of the Musical Workmen of France and England was greeted with every courtesy by the proposed French participants, but opposed from ‘other parties’, by which he presumably meant the Board of the Crystal Palace. Far from being distracted by other interests, in April 1864 Jackson had been involved in negotiations to run an international contest with Bowley and the Board of the Crystal Palace Company. The letter makes it clear that no brass band competition would be considered along the lines of those held in previous years. The discontinuance of the contests was effectively announced in this letter to Jackson from the Crystal Palace Company, signed by Bowley.

Jackson Autobiography

Much of what has been written about the Crystal Palace series of brass band contests in the 1860s has been based on the Jackson autobiography. This reliance on Jackson's recollections can now be shown to be seriously problematic in any consideration of the facts. Jackson made a number of claims in support of his assumed success with the contests, yet much of what he wrote was an attempt to manipulate his legacy.

One of the most startling claims in Jackson's autobiography comes in his story of how the brass band contests were preceded by a handbell-ringing contest held in 1859. According to Jackson, the Crystal Palace Company tested his abilities by asking him to organize a contest for 12 teams of handbell ringers in that year. He took 12 of the best bands of that class in England and ‘achieved a success wonderful in its way, which has not since that time been attempted’.Footnote 76 This ‘fact’ has been alluded to earlier and is repeated in almost every study of the Crystal Palace brass band contests as the model for his future success.

The truth is, however, that there was no contest of 12 teams of handbell ringers in 1859; the event that Jackson organized was an appearance at the Crystal Palace by two teams of handbell ringers, from Barnsley and Holmfirth, near Sheffield. These two groups appeared on Saturday 15 October, Monday 17 October, and Tuesday 18 October 1859. The appearance was billed as an ‘Instrumental Concert’ by two companies of Yorkshire handbell ringers.Footnote 77 It was further advertised in other London newspapers. The Saturday admittance was charged at half a crown with 926 visitors paying for entry. Monday and Tuesday were charged at one shilling per visitor (half price for children over three years of age but under 12). The event was not a contest, but a demonstration of the art of handbell ringing. There were only two teams of 12 members each participating. The Barnsley Chronicle describes the event in glowing terms and compares the whole event to a competition, whereby the Barnsley handbell-ringing team outplayed the Holmfirth ringers.Footnote 78 The account of the handbell-ringing event at the Crystal Palace as recounted in Jackson's autobiography is thus inaccurate, it is hard to take at face value any of his recollections of the landmark events that were the Crystal Palace brass band contests.

Inflation of Numbers of Participating Bands

One of the constant themes in the above analysis is the inflation of numbers of bands competing. Not one of the six contests in the Crystal Palace series matched the attendance anticipated in pre-contest press advertisements. It is of course inevitable that some bands would fail to appear, but where evidence is available it is apparent the proportion of absences were in the region of 50 per cent. This continual overestimate indicates that Jackson deliberately inflated the list of bands entered to increasing the anticipated spectacle of the occasion in the full knowledge that fewer bands would attend. This was not confined to one unfortunate event, as we have seen, but amounted to a stratagem – a series of contrived manipulations by Jackson to exaggerate the scale of the event.

This ploy was not limited to Jackson's Crystal Palace events. The very first brass band contest that Jackson organized was held at the Hull Zoological Gardens on Monday 30 June 1856. Of 21 bands entered, only 14 made their appearance, two of which withdrew from the contest apparently on seeing the calibre of the bands they were playing against.Footnote 79 Both were local Hull bands and this withdrawal would not have involved any great inconvenience to the players. The contest was very well attended and probably a financial success, but a third of the bands entered did not appear.

A further brass band contest that Jackson organized – together with a business associate, Robert Alderson – was held at the Newhall Gardens, Sheffield, on 14 June 1858. Interestingly, this is the only example of a contest with an advertisement asking for entrants that has so far come to light.Footnote 80 The entrance fee for the brass bands was half a Guinea (ten shillings and sixpence).Footnote 81 27 bands were advertised as competing in the contest,Footnote 82 but only 16 made an appearance. The Sheffield Independent gave a more detailed report a week later which stated ‘the number of bands present was 26, but the contest was limited to the following 16’ and then listed the competing bands.Footnote 83 The Sheffield Daily Telegraph gave an even more detailed report, although did not pretend to have enjoyed the experience, giving a less than flattering description of the sound of the bands they heard. This report stated that 27 bands had entered but not more than 16 or 17 proceeded to the trial.

Describing the events of the day, the Sheffield Independent stated that 26 bands were present, but the contest was limited to just 16 bands.Footnote 84 Several other newspaper accounts confirm that a number of bands were present but did not play as implied in the Sheffield Independent. Of the bands that did not perform, three had entered from Lincolnshire, travelling approximately 80 miles to reach the contest venue, whilst two bands had entered from Sunderland, a distance of approximately 120 miles. It seems to be a peculiar idea that bands would pay money to enter a contest and travel such long distances, only to decide not to play as inferred in the report from the Sheffield Independent. A further entrant not appearing was the Holbeach Brass Band, who had also failed to appear for the Hull Zoological Contest organized again by Jackson at the Hull Zoological Gardens in 1856. It is more likely that the names of these bands were entered in the full knowledge that they would not appear, but to make the list of contenders, and therefore the contest itself appear more impressive.

A further example of this Jackson trait is exhibited at a contest held at the Trent Bridge Cricket ground on 10 September 1860. This contest attracted an entry of 12 bands, and the proceedings were reported in detail by the Nottinghamshire Guardian on 13 September 1860.Footnote 85 The report listed the band title, names of the leaders of each ensemble and the pieces they played. One of the bands was the 1st Boston Lincolnshire Artillery Volunteers band, led by their bandmaster Mr Keller, but the Stanford Mercury newspaper of 21 September 1860 claimed that neither Keller nor the band had any knowledge of their entrance to the contest. Not only had the band not attended the contest, but no communication had ever passed between the band and the organizers of the contest. The report concluded ‘to say the least of such conduct, it is remarkably cool, and belongs to the Barnum order of doing things. We hope that the managers of the Boston contest were more honourable than this’.Footnote 86 The American showman, Phineas Taylor Barnum, was known for his use of sensational and exaggerated publicity to popularise his events. He had also attracted notoriety for his exhibits that were later found to be hoaxes. The reference to the managers of the Boston Brass Band Contest was a direct allusion to Jackson, who was also an organizer of this contest.

Band Participation Analysis

The above examples demonstrate three aspects of Jackson's approach to handling the list of entrants to any competition he organized. First, he had access to a large amount of detail about bands, including the names of ensembles and their respective leaders. This is borne out by the detailed list of entrants advertised in the Bell's Sporting Life newspaper, whereby every band had a conductor or leader named in the advertisement. Second, this detail was used in advertisements in the full knowledge that some bands were not aware they had been entered and it was therefore certain they would not attend the contest. Third, Jackson knew the newspapers would use the official information he circulated himself without questioning the accuracy of the detail contained. It is possible the list of entrants for the contest at Trent Bridge Cricket ground contained even more bands that were unaware they had been announced as entrants to the contest. The overall decline in the numbers of participating bands is demonstrated in Table 4

Table 4 Competing bands analysis: Crystal Palace Brass Band Contests 1860–1863

Summary of Reasons for Discontinuance

The period of the Crystal Palace contests was one of unprecedented growth in brass band contests, yet ironically this may have contributed to a falling away of support for the Crystal Palace contests. The prize money on offer was generous, in the first two years, and it is notable that some of the top contesting bands supported the events and were successful in their placings. However, participating in the contests in the capital entailed costs for accommodation and food that would have depleted funds, even if a band was fortunate enough to win prize money in the midst of such a large entrance field.

Jackson organized many large-scale contests and had a coterie of bands that appeared regularly. Even Bramley Temperance Band, whom Jackson had publicly disqualified from the initial 1860 Crystal Palace contest, seemed to have been forgiven, appearing at a contest organized by Jackson at York in 1861. This event drew 25,000 visitors for the day.

In some ways the initial Crystal Palace contest may have been a victim of its own success. The publicity generated attracted the interest of other promoters: when a contest was held in Exeter in July 1861, the announcement advertising the contest stated it was intended to hold ‘one of those band contests which annually draw thousands to the Crystal Palace’.Footnote 87 There were a number of contests held during the summer of 1861 that provided rival attractions to travelling to the Crystal Palace.

Broader economic changes during this period also had an impact: the effects of the American Civil War were beginning to be felt in 1861 in the regions of the country concerned with the cotton industry. The ‘cotton famine’, as it became termed, caused great distress amongst the lower class, particularly in Lancashire and some parts of Yorkshire. The top bands did not appear to be affected – Black Dyke Mills Band was active in various parts of England throughout this period – but smaller, less proficient bands would have felt the effects wrought by the resultant blockade of produce from the southern states of America. Evidence of this can be found in a letter in the Roy Newsome Brass Band Archive. The letter is from the leader of the Kirkburton Band near Leeds regarding their attendance at the Crystal Palace contest in 1861.Footnote 88

Kirkburton July 16th 1861

Sir,

I am sorry to inform you that we the members of the Kirkburton Temperance Brass Band cannot attend the Band Contest held Sydenham on 29Footnote 89 inst on account of being short of employment our present circumstances will not allow it,

From your truly

J. Charlesworth LeaderFootnote 90

An additional factor with the 1861 Crystal Palace contest is that it involved an extra day in London. This may not have been a problem to bands based in the South, but it would have been a factor in the decision of bands from the North whether to compete or not. The 1861 contest shows a growing attendance from bands based in the midlands and southern England, probably because locally based bands did not have to incur the costs of stopping in London, or the bands were travelling from areas unaffected by the financial impact of the cotton famine experienced in the northern districts.

Leaving aside the vexed issue of which bands did attend the competition at the Crystal Palace, the event suffered an overall decline in entrants from the first year onwards. Only 27 individual bands competed in the 1861 competition, 26 in the one-day event in 1862, and a reported 21 but more likely 14 in 1863. All these numbers contrast sharply with the numbers of bands advertised; but viewed against Jackson's propensity to inflate numbers this is not unremarkable.

The visitor totals attending the contests are respectable, but they do not represent significant spikes amongst the general running of the venue. The company expected large numbers of visitors, and attractions such as the appearance of M. Blondin drew vast crowds to watch his high wire acts. There are a number of references to the brass band competitions not troubling the excursion trains that had been laid on to accommodate visitors, as well as competing events held around the time of the competition that made visitors choose which event they wished to attend, often to the detriment of the contests. The Dover Express remarked that over a thousand people had travelled to the Crystal Palace the previous week on a trip organized by the Dover Working Man's Institute. The growing popularity of the events at the Crystal Palace meant that the lower classes were choosing from a greater variety of events to attend than previously. One of the special excursion trains for the 1863 contest only attracted 24 travellers from Stamford on the Great Northern Railway.Footnote 91

One of the reasons previously put forward for the discontinuance of the contests is the death of Bowley in 1864, but this is clearly unfounded since he lived until 1870. Bowley obviously had a good working relationship with Jackson at the beginning of the contests, as witnessed by his appearance at the awards ceremonies and his praise of Jackson (reported by the media), but it is obvious from barbed comments in his autobiography that Jackson had a dislike of the secretary of the Crystal Palace Company, George Grove. Jackson states that Bowley would not entrust the running of a brass-band contest at the Crystal Palace to anyone else, despite Bowley signing the letter that effectively ended Jackson's activities there, so it may be that Grove was behind the decision and Jackson recognized that Bowley was simply following the Board of Directors’ instructions in writing to him as he did. Jackson's insistence, in his autobiography, that his five years’ service to the company resulted in financial successes is contradicted by the letter he received from Bowley and should be understood as his attempt to shore up his reputation as a successful entrepreneur.

Grove's letter to Jackson in 1862 makes it clear that the contest was to be arranged with a participation of no fewer than 20 bands. That was a condition of the terms agreed, so there is therefore no reason to suspect this was not a similar requirement for the 1863 contest. Twenty-six bands attended in 1862, as far as can be established. Considerably fewer attended in 1863 – well below the 20-band requirement – yet all of the reports available contain the phrase ‘twenty one bands attended’. This points to the conjuring of a smoke screen that would have been difficult to disperse were it not for the two surviving contest remarks sheets. It is probable that Jackson composed and sent the reports for publication in the newspapers, and in 1863 he was still hoping for a better year in 1864, but is incontrovertible that the overall trajectory of brass band participation in the series of contests organized by Jackson at the Crystal Palace was downwards from the opening year.

Conclusion

These contests clearly show the popularity across England and Wales of brass bands, which had only emerged as a distinct musical identity within the previous decade. Jackson undoubtedly made a huge contribution to the development of this movement; his contests gave a national dimension that was important in the beginnings of standardization in rules for these ensembles. As Denise Odello has noted, a national network results in regulation and codification.Footnote 92 Jackson began this process with his far-sighted decision to organize brass band contests on a national level; however, his writings in later years reveal that he was possessed of a strong sense of self-belief but was embittered by his short involvement at the height of brass band popularity, as well as evidence of manipulation of the truth to enhance his own personal reputation.

That the decision to discontinue the brass band competitions at Crystal Palace was made on a financial basis is evidenced by the letter to Jackson signed by Bowley in 1864. Although there is no other documentation of the discussion between Jackson and the Company apart from this one letter, it confirms that a lack of financial viability – the journey from ‘extraordinary success’ to ‘failed in realizing any considerable results’ – was the single most important reason for the cancellation of brass band contests at the Crystal Palace.