1. Introduction

Norwegian is a language that generally adheres to a strict word order, but there are nevertheless certain structures in which alternations are possible. One relevant example is the so-called dative alternation (DA), in which the order of the two objects of ditransitive verbs may vary. The two structural variants are typically referred to as the double object dative (DOD), e.g. Liv ga gutten eplet ‘Liv gave the boy the apple’; and the prepositional dative (PD), e.g. Liv ga eplet til gutten ‘Liv gave the apple to the boy’. In the former, the indirect object (IO), realizing the recipient or beneficiary of the verbal action, precedes the direct object (DO), or theme, while in the latter, the opposite order occurs, and the recipient is realized by a prepositional phrase.

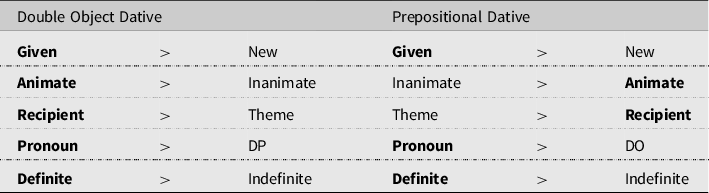

Several factors have been found to influence the order of the object arguments, such as givenness, pronominality, definiteness, animacy, and weight (Bresnan & Nikitina Reference Bresnan and Nikitina2003, Bresnan et al. Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina and Baayen2007, Bresnan & Ford Reference Bresnan and Marilyn2010, de Marneffe et al. Reference de Marneffe, Grimm, Arnon, Kirby and Bresnan2012). In this paper, we focus on the first two factors and aim to explore what effect they have on speakers’ preferences when it comes to double object structures in Norwegian. The two factors are clearly connected; givenness refers to the information structural status of a referent, and whether it has been previously introduced in the discourse or not. The choice of referring expression is usually determined by the givenness of the relevant referents, with pronouns and definite noun phrases being used with given elements and indefinite noun phrases with new ones (Gundel, Hedberg & Zacharski Reference Gundel, Nancy and Ron1993). Givenness also guides word order in the sense that given arguments generally precede new elements (the given-before-new principle; Clark & Sengul Reference Clark and Sengul1979). Thus, givenness affects both the order of arguments in a clause and the choice of referring expression. In fact, the different factors typically align, such that they reveal a preference for a definite, pronominal, animate, and/or light argument to precede one that is indefinite, non-pronominal, inanimate, and heavy. In the literature this is referred to as harmonic alignment, that is, the tendency for linguistic elements that are more or less prominent on a scale to be disproportionally distributed in respectively more or less prominent syntactic positions (Bresnan & Ford Reference Bresnan and Marilyn2010:183). As we will see, however, harmonic alignment is more a property of DODs than PDs. Even though all of the factors listed above clearly are at play in DA, we will focus on givenness and pronominality and explore what effect they have on speakers’ preferences when it comes to double object structures in Norwegian.

In order to investigate the effect of givenness on the DA, we developed a speeded acceptability judgment task in OpenSesame (Mathôt, Schreij & Theeuwes Reference Mathôt, Schreij and Theeuwes2012) that measures the reaction times (RTs) of the participants’ responses to test sentences which they were asked to judge as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Based on previous studies conducted on languages with DA (Clifton & Frazier Reference Clifton and Lyn2004, Brown, Savova & Gibson Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012, Kizach & Balling Reference Kizach and Laura2013, Kizach Reference Kizach2017), we expected there to be a significant difference in the RTs between the conditions conforming to and the conditions violating the given>new principle in the DOD, whereas no difference should be observed for the PD. All the former studies on dative alternation making use of RT data tested structures with noun phrase objects. The current study takes the investigation of DA one step further by including pronominal (given) objects as well. We expected slower reaction times when pronominal objects violated the given>new order (e.g. ‘She gave an apple to him’, ‘She gave a boy it’) than when DP (given) objects did so (e.g. ‘She gave an apple to the boy’, ‘She gave a boy the apple’).

The paper is structured as follows: The next section presents previous studies of DA making use of online measures in English and Danish, languages that share the dative alternation with Norwegian, followed by an outline of the dative alternation in Norwegian. Next, the goals of the current study and our research questions are provided, followed by the methodology in Section 3. The results are described in Section 4 and discussed in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Effect of givenness and pronominality on dative alternation

The factors that influence the choice of object order in ditransitive structures are numerous; for a full overview (for English) see Bresnan & Nikitina (Reference Bresnan and Nikitina2003), Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina and Baayen2007) and de Marneffe et al. (Reference de Marneffe, Grimm, Arnon, Kirby and Bresnan2012).Footnote 1 These studies reveal a preference for a definite, pronominal, animate, and light argument to precede one that is indefinite, non-pronominal, inanimate, and heavy. This is referred to as harmonic alignment, as linguistic elements that are more or less prominent on a scale tend to be disproportionally distributed in respectively more or less prominent syntactic positions (Bresnan & Ford Reference Stephens2010:183). There are clearly a multitude of factors involved in the choice of dative structure, but there is a general tendency for arguments to have more than one prominent/non-prominent feature, i.e. pronominal arguments are typically also given and light.

Givenness is a key element of the study of information structure. The given-before-new peinciple (henceforth given>new) was first introduced by Clark & Haviland (Reference Clark and Haviland1977) and focuses on the syntactic distinction that the speaker has to make between what is old information and what is new to the listener. The authors suggested that sentences are easier to process when given information precedes new information; there is overwhelming evidence from previous research that, all other things being equal, speakers prefer for given information to precede new (Birner & Ward Reference Birner and Ward2009), see e.g. Arnold et al. (Reference Arnold, Losongco, Wasow and Ginstrom2000), Kaiser & Trueswell (Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2004), Røreng (Reference Røreng2011), Burmester, Spalek & Wartenburger (Reference Burmester, Spalek and Wartenburger2014), Hung & Schumacher (Reference Hung and Schumacher2014).

Studies investigating the relationship between givenness and dative alternation in English (Clifton & Frazier Reference Clifton and Lyn2004, Brown et al. Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012, Bridgwater, Kyröläinen & Kuperman Reference Bridgwater, Kyröläinen and Kuperman2019) and Danish (Kizach & Balling Reference Kizach and Laura2013) have tested this by using speeded acceptability (Clifton & Frazier Reference Clifton and Lyn2004, Kizach & Balling Reference Kizach and Laura2013) and self-paced reading tasks (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012). However, these studies did not include pronouns among their test items; all the objects were expressed by definite or indefinite DPs. All the studies found a givenness effect on the DOD. The speeded acceptability tasks reveal significantly higher acceptability and faster RTs with DODs when the first object is definite and the second one is indefinite than the other way around; this difference is not found with the PD. These observations are corroborated in a memory recall experiment in Danish (Kizach Reference Kizach2017) where the participants had no trouble correctly repeating DOD sentences in which the first object was definite and the second indefinite, but they altered the definiteness of the sentences with indefinite–definite order at 94%. Clifton & Frazier (Reference Clifton and Lyn2004) tested the effect of givenness on both DODs and PDs in a task which included a context sentence introducing one of the object arguments, in addition to definiteness marking in the target sentences. In the task with no explicit context, definite>indefinite structures yielded faster RTs in the DOD. In the PD this preference was not only absent, but indefinite>definite orders resulted in faster RTs. In the task with added context, however, there was no change for the DOD, as given>new orders still had shorter RTs, but there was no longer a preference for new>given orders for PDs. Thus, the addition of context sentences has an effect on the processing of these structures.

The effect of givenness on the DOD was also found in the self-paced reading task in Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012). The participants read the second object significantly faster in DODs with given>new compared to new>given order, while for the PD there was no significant difference between the two (in fact, new>given was marginally faster). Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012) also test whether the dispreference for the DOD in contexts in which the recipient is new is due to the presence of an indefinite animate argument. The results for the test items in which both object arguments are animate suggest that this is not the case. For DODs, given>new structures are processed significantly faster, even when both objects are animate.

All of the studies outlined above suggest that the DOD is context-sensitive whereas the PD is not. Clifton & Frazier (Reference Clifton and Lyn2004) and Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012) argue that this is due to the non-canonical status of the DOD, as non-canonical structures are licensed only when contextually appropriate in the discourse.

In our task we also test the effect of pronominality. According to accessibility theory (Ariel Reference Ariel1990), more accessible arguments are more likely to be expressed by pronouns. Accessibility has three hierarchically ordered context types: general knowledge, physical surroundings, and previous linguistic material (Ariel Reference Ariel1988:68), the last one being what we mean by givenness here. Relatedly, when we look at the givenness hierarchy formulated by Gundel et al. (Reference Gundel, Nancy and Ron1993), referring expression and givenness are strongly intertwined, as what is the most appropriate referring expression is dependent on the givenness status of the referent. This way, pronominality goes hand in hand with givenness. The linearization of pronouns follows the given>new principle, as pronouns tend to precede non-pronouns (e.g. DPs). Violations of the given>new order with pronouns may thus be expected to be perceived as worse than violations involving definite DPs. Stephens (Reference Stephens2010) investigated the effect of discourse in English child language but included an adult control group. The participants had to describe a vignette by using a dative structure, for which the subject and either the theme or the recipient were given. They were free to use either pronouns or DPs to denote the items. Stephens (Reference Stephens2010) found that when participants used the DOD, they were unlikely to use a pronominal theme, making PDs the only structures in which pronominal themes can occur (as in e.g. He gave it to the woman).

Kizach & Vikner (Reference Kizach and Sten2018) conducted a corpus study in the online Danish corpus Korpus DK (available at: http://ordnet.dk/korpusdk) which included an analysis of the effect of pronouns. The authors found that pronoun-first is the dominant order in both DOD and PD constructions. However, a closer look at the data revealed that pronouns are used much more often in the DOD (59% of recipients were pronominal) than in the PD (9% of themes were pronominal). Thus, the use of referring expressions seems to affect the choice of structure. Similarly, Larson (Reference Larson1988) has claimed that DOD structures with a DP recipient and a pronominal theme are ungrammatical (e.g. *He gave the patient it) in English. This is further confirmed by a corpus analysis on DA structures conducted by Arnold et al. (Reference Arnold, Losongco, Wasow and Ginstrom2000) which revealed that 40% of recipients and only 2% of themes were pronominal.

There are relatively few studies of the dative alternation in Norwegian, and even fewer related to the role that information structure plays when it comes to object order. The only previous study that discusses this is Anderssen et al. (Reference Anderssen, Rodina, Mykhaylyk and Fikkert2014), which argues that the dative alternation in Norwegian is dependent on givenness and that this applies to both PD and DOD. Even though Anderssen et al. (Reference Anderssen, Rodina, Mykhaylyk and Fikkert2014) is a child language elicited production study, there was a small, adult control group, and the adults mainly used the pragmatically most appropriate object order. The authors do not comment on the use of referring expressions in the adult controls, but they clearly show a sensitivity to givenness in the choice of word order. The PD structure was typically used when the theme was given (74%) and the DOD was used when the recipient was given (88%).

3. The current study

In this study we want to investigate whether the patterns observed in Danish and English related to the information structural requirements of ditransitives can be found in Norwegian as well. The results from the elicited production task in the child language study reported in Anderssen et al. (Reference Anderssen, Rodina, Mykhaylyk and Fikkert2014) suggests that this is the case, both in child language and in the very limited adult control data.

In the current task, we rely on explicit context to introduce the given element in the test structures in order to ensure a more natural setup in terms of what is given and what is not. We also make use of two measures, offline explicit acceptability judgements and online implicit reaction time measures.

The effect of pronominality was also tested in the current task. We expect pronominality to reinforce givenness in the sense that the preference for given>new found with DODs in previous studies is expected to be stronger with pronominal objects. The question is whether such an effect will be found with PDs as well. One the one hand, PDs may be less influenced by pronominality, as given themes tend not to be pronominal (Kizach & Vikner Reference Kizach and Sten2018); on the other, pronouns may reinforce the given>new principle.

Thus, the main goal of this paper is to investigate how givenness and pronominality affect the acceptability and RT of alternating dative structures in Norwegian. This adds to the body of research already conducted on other languages with the same type of alternation with ditransitives, i.e. English and Danish; but it also consistently includes contexts and adds pronominality to test (i) how it interacts with givenness and (ii) whether there is any cumulative effect of the two factors.

The aim of the paper is to answer the following research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1. To what extent are ditransitive structures that violate the given>new principle accepted as grammatical in Norwegian?

-

RQ2. To what extent is information structure reflected in RTs?

-

RQ3. To what extent does the choice of referring expression (DP vs. pronoun) affect the acceptability and RTs of double object structures?

-

RQ4. Is there a general effect of referring expression on structure (DOD vs. PD)?

Previous research has found that most of the items are judged as acceptable, but this was for studies including DPs only. We also expect structures involving given DP to be mostly considered ‘good’. However, pronominal given objects might yield a different result, as English DODs with pronominal themes have been claimed to be ungrammatical (Larson Reference Larson1988, Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Losongco, Wasow and Ginstrom2000) or at least strongly dispreferred (Stephens Reference Stephens2010). If this holds for Norwegian, DODs violating the given>new principle with given pronominal objects should be judged as ‘bad’ (RQ1). Similarly, we expect RTs to be significantly faster with the DOD when it occurs in accordance with the given>new principle compared to those contexts in which this word order violates this principle. The PD should show no such effect, if Norwegian behaves the same way as Danish and English (RQ2). A different pattern might emerge when the given object is expressed by a pronoun (RQ3). We expect the same differences in judgements and RTs to hold for the DOD, perhaps even more strongly, as both givenness and pronominality are ‘pulling’ in the same direction. Thus, we may observe even slower RTs in new>given orders in DODs when the given object is also a pronoun. With regard to the PD, if it is truly insensitive to context, pronominality should not affect it. However, if acceptability or RTs are affected, this will indicate that the PD is not as independent as previously assumed; it might just be less sensitive than DODs. The final question relates to whether the choice of referring expression will affect both structures the same way (RQ4). We know from Danish corpora that DODs are much more likely to appear with a pronominal recipient (59%) than PDs are to occur with themes expressed by pronouns (9%) (Kizach & Vikner Reference Kizach and Sten2018). If this general distribution holds for Norwegian as well, referring expression may affect the two structures differently.

According to harmonic alignment the different factors affecting DA tend to be aligned. Naturally, factors like animacy and weight might still be at play even if they are not directly controlled for in this study. Our test items had prototypical animacy, i.e. animate recipients and inanimate themes, and weight may also play a role, especially in items with pronominal objects, as these are invariably lighter than the indefinite DPs. Thus, weight reinforces givenness and pronominality, even though it is not a factor that is being tested. Also, note that Harmonious alignment does not apply between animacy and givenness/pronominality in PDs in our design, as it does not do so prototypically. One might question whether this lack of alignment might explain the absence of a givenness effect in PDs in previous studies. Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012) has shown that the preference for given>new is also present in DOD structures with two animate objects, but this does not mean that animacy does not affect PDs, in which the inanimate object precedes the animate one.

4. Methodology

4.1 Participants

Thirty-one Norwegian native speakers completed the study. The sample contained 20 female, 10 male, and one non-binary participants. The participants were recruited through social media in the Tromsø area and with fliers on campus of the University of Tromsø, and they were awarded with a cinema ticket with a value of approximately 15 euros upon completion of the task, which took approximately 20 minutes to complete. Each participant received a sequential numerical ID at the testing; unfortunately, due to a compiling error, two participants were given the same ID, and it was thus not possible to detangle them in the data analysis phase.

4.2 Materials

A speeded acceptability task was designed using OpenSesame (Mathôt et al. Reference Mathôt, Schreij and Theeuwes2012). Each test item, including fillers, consisted of a context and a target sentence, thus ensuring that given elements had been previously introduced. The participants had to either accept or reject these sentences in their contexts, while the reaction times of their responses were measured.

The task consisted of three groups of sentences: target ditransitive sentences, transitive sentences (which were target sentences for a different study), and fillers which were divided into grammatical/ungrammatical or pragmatically felicitous/infelicitous variants. There was a total of 256 items. The full list of items will be found in appendix Tables A1–A4.

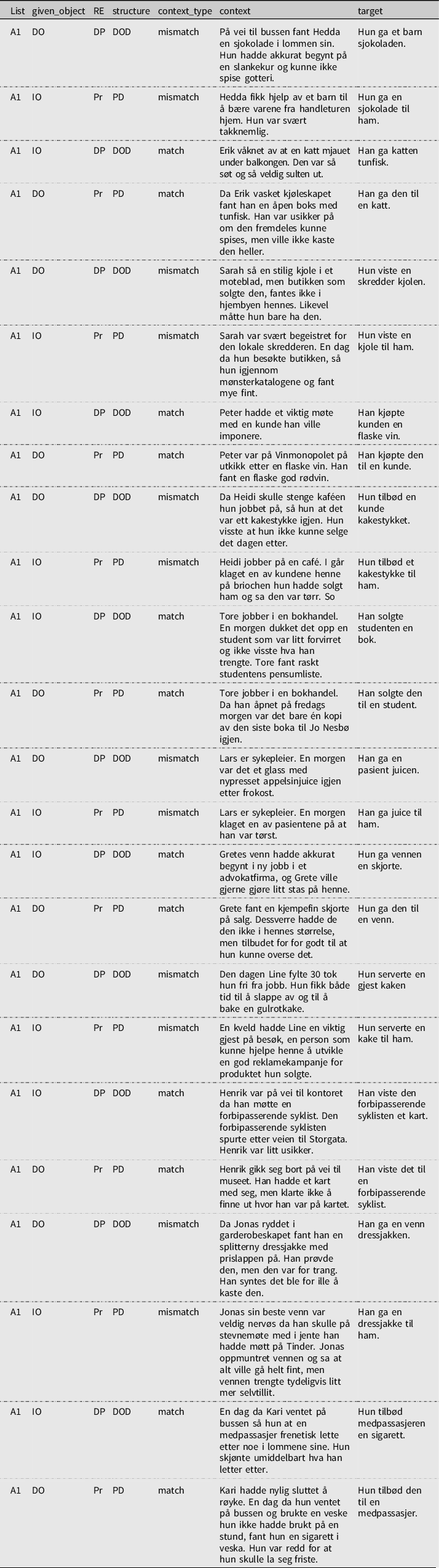

There were three dependent variables: structure (PD vs. DOD), given object (DO vs. IO), and the referring expression of the given object (DP vs. Pronoun), giving us a 2 × 2 × 2 (= 8) matrix of target sentences for each example. The new objects were always expressed with an indefinite DP. There was a total of 12 examples amounting to 96 test items. The items were evenly distributed between two lists (A and B) so that a single participant would not see all eight variants of the same test item, but rather four. These lists were further divided into two blocks (A1 and A2, B1 and B2), each containing only two ditransitive items of the same example. This allowed us to pseudo-randomise the items by avoiding that items of the same example appeared in the same block. Half of the participants (n = 15) were assigned to list A and half (n = 16) to list B.

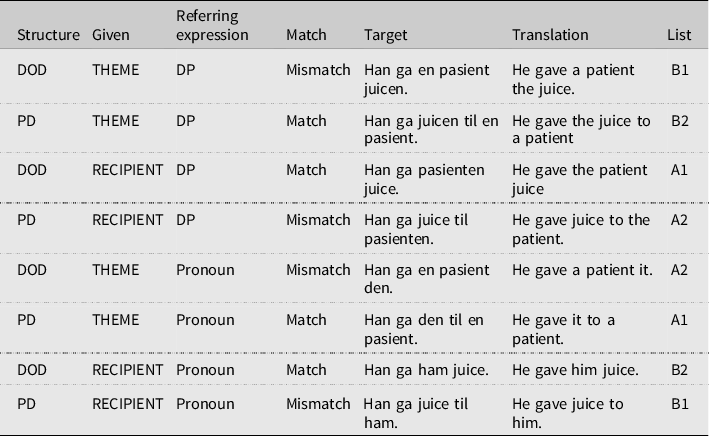

The items were coded as match or mismatch depending on whether the word order of the structure (DOD or PD) reflected the given>new principle. In the former the given>new order is preserved, while in the latter, it is violated. Thus, match within the DOD means that the recipient is given and the theme is new, while the opposite is true for match PD items.

A matrix of one of the examples is displayed in Table 1. The list column (A1/B1 or A2/B2) specifies in which list and block that item was placed. In order for the participants to be tested on the full array of conditions, they saw four items from one example and four from another, such that each participant responded to the same number of structures in which the objects were realized by DPs or pronouns, the DO or the IO was given, and the DO preceded the IO. Examples of contexts in which the items appeared are provided in (1).

Table 1. Test items in different conditions distributed over lists A and B.

-

(1)

4.3 Fillers

The ratio of fillers to test items was approximately 3:1. The fillers consisted of transitive items (n = 72) which were the target structure for another study and contained both grammatical and ungrammatical items. In addition, there were 44 items that only had the function of fillers. These were either grammatical/ungrammatical (n = 20) or pragmatically felicitous/infelicitous (n = 24). The fillers included a context and a target sentence that was judged as good or bad. All of the test items will be found in appendix Tables A5–A7.

4.4 Procedure

The participants gave their consent to participate and filled in a background questionnaire, and completed a practice loop with items. The task was organized into two blocks, and participants had the possibility of taking a break after the first one.

The test was structured as follows. First the context sentence appeared on the screen. For longer contexts this was spread over two lines. When the participants had finished reading it, they had to click the mouse button to continue. When the target sentence appeared, the mouse cursor was moved automatically to the centre of the screen by using the Mousetrap extension (Kieslich and Henninger Reference Kieslich and Felix2017). This ensured the same distance from both response buttons, and the RTs were measured from this point. With the target sentence, two buttons, one with ‘good’ and one with ‘bad’ written on it, appeared on the screen, one on the left and one on the right. The placement of the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ button was constant throughout the experiment.

5. Results

The statistical package R was used to run the statistical analyses, including lme4 (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Machler, Bolker and Walker2015 ) and lsmeans (Lenth Reference Lenth2016) packages.

5.1 Acceptability judgements

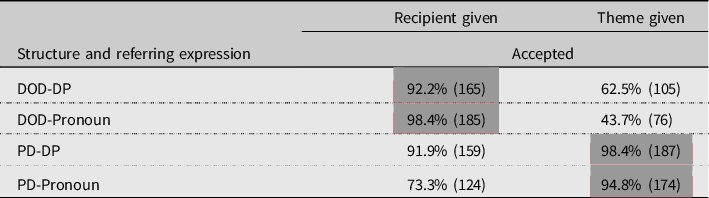

Here we focus on the mean acceptability ratios in the dataset. Table 2 includes acceptance ratios for all responses.Footnote 2

Table 2. Proportion of accepted sentences in the different conditions. The results for the pragmatically felicitous conditions appear in shaded cells; the raw numbers are in parentheses.

Pragmatically felicitous examples are accepted at a very high rate, 92–98%. When both object arguments are realized by DPs, DODs are accepted at 92% in match contexts. In mismatch contexts, they are only accepted 63% of the time. When the given object is realized by a pronoun, the difference is even larger; pragmatically appropriate DODs are accepted at 98% and inappropriate ones at 44%. The latter is a very low acceptance rate compared to what has been found in earlier studies and could be indicative of a qualitative difference between the structures (Larson Reference Larson1988, Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Losongco, Wasow and Ginstrom2000).

As in previous studies (Clifton & Frazier Reference Clifton and Lyn2004, Brown et al. Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012, Kizach & Balling Reference Kizach and Laura2013), the PD appears to be less sensitive to pragmatic context, at least when the given theme is realized by a DP. In these cases, the difference in the acceptability rate between match and mismatch orders is 98% vs. 92%. Interestingly, however, there is a clearer difference when given objects are realized by pronouns: 95% vs. 73%.

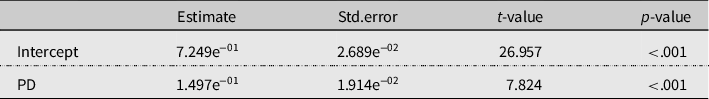

We first ran a linear mixed effect analysis with response type as the dependent variable and the structure as our independent variable; participant and test item were set as random effects (see Table 3). The other factors were not included for this preliminary analysis. The DOD is set as the intercept; The random intercept was estimated at SD 0.10508 for participants, and SD 0.04508 for test item.

Table 3. Statistical comparison of the acceptability of the two structures.

The model reveals that there are significantly more ‘good’ than ‘bad’ responses in the DOD (intercept), as expected from the raw data; and we can also see that the PD has significantly more ‘good’ responses than the DOD. In order to grasp the source of this effect, we ran subsequent statistical models separately for DOD and PD: two linear mixed effects regressions were fitted for the two structures. Context type (match/mismatch) and referring expression were set as fixed effects and participant and test item as random effects. The model also tested for interaction between the fixed effects. The intercept is set for match and DP object. The random intercept of the DOD model was estimated at SD 0.1415 for participants, and SD 0.1124 for test item. The results are displayed first for the DOD (Table 4), followed by the PD model (Table 5).

Table 4. Statistical analyses on the acceptability rate of DODs.

Table 5. Statistical analyses on the acceptability rate of PDs.

The result of the intercept entails that there are significantly more ‘good’ responses than ‘bad’ responses. The model shows that the acceptability is significantly lower when the order is new>given (p < .001, 92% vs. 62% in Table 2 above). The acceptance rate for pronominal recipients is higher than for DP recipients in given>new order (p < .05, 98% vs. 92%). Finally, we can note a strong givenness by referring expression interaction as givenness has a larger effect for pronouns than for DPs.

The same test was applied to the PD structure, reported in Table 5. The random intercept for participants was estimated at SD 0.06807, for test item at SD 0.05814. Again, the statistical significance of the intercept reveals that there are more ‘good’ than ‘bad’ responses. We find that the PD is significantly less likely to be accepted in the new>given order (p < .001, 91.9% vs. 98.4%). This is consistent with the pragmatics of the structure, but nevertheless unexpected, as previous studies have suggested that the PD is not sensitive to context. Furthermore, we can see that the acceptance is lower when the recipient is pronominal, but not to a significant degree. Lastly, there is an interaction between givenness and referring expression which means that givenness effects DP and pronominal objects differently. This is evident also from the percentages of rejection rates in Table 5, as mismatch PDs with pronominal objects are rejected at a rate of 73.3%, contrasted to the rejection rate of 91.9% for the DP items.

5.2 Reaction times (RTs)

Having established that the acceptance ratio differs depending on information structure for both alternates, let us turn to RQ2 and the differences in reaction times, bearing in mind that this is a subconscious online measure. The mean RT for the full dataset is 3376 ms, while the median is 2907 ms. However, the RTs of ‘bad’ responses were slower overall, with a mean 4123 ms compared to a mean of 3447 ms for ‘good’ responses. We have thus decided to focus on the RTs of ‘good’ responses only, as the majority of ‘bad’ responses involved DODs (161/210) and thus including all responses would result in an RT bias against the DOD. A less advantageous consequence of this is that most of the answers excluded in this section are responses to the DOD structures.

The mean RTs divided by condition are displayed in Table 6. All trials above 8500 ms were excluded, leaving us with a total of 1147 observations (521 DODs and 626 PDs).

Table 6. Average RTs for the ‘good’ trials. Shading marks the pragmatically felicitous conditions.

The overview above reveals that the RTs for the conditions in which word order violates the given-before-new principle are consistently longer than those in which word order is in accordance with this principle, by 100–500 ms. Subsequent statistical tests will show whether the difference in RTs is significant.

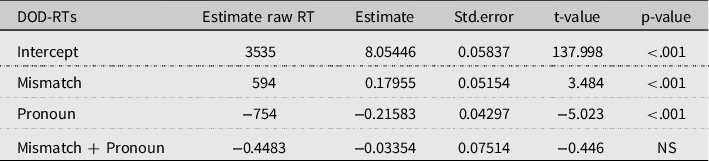

The RTs were transformed into logarithmic values in order to conform to normality, and linear mixed effects regressions were applied on these responses. Context and referring expression were set as fixed effects; participant and test item were set as random effects. The model tested for interaction between the fixed effects. We report the results of the model on the logarithmic data, but we nevertheless display also the estimate of the raw RTs to reveal the magnitude of the effect of the conditions on the RTs. The results are displayed in Tables 7 and 8, separately for each structure. The intercept is set to DP object and match context. The random intercept for participants was estimated at SD 0.22281 and for test item at SD 0.09606. The mean and median RTs for the DOD structure are 3355 ms and 2907 ms, respectively.

Table 7. Linear mixed effects of the DOD.

Table 8. Linear mixed effect of the PD.

The results in Table 7 confirm that the mismatch conditions are significantly slower than the match conditions for DODs (RQ2). The RTs of the items with a pronominal given object in the match condition are significantly faster than the DP items. Finally, we can see from the model that there is no interaction between condition and referring expression, which means that for the DOD givenness has the same effect on both referring expressions when it comes to RTs (RQ3).

The results from the analysis of the PD responses follow in Table 8. The fixed, random effects, and the intercept were set the same way as for the DOD model. The random intercept for participants was estimated at SD 0.19354 and for test item at SD 0.09485. The mean and median RTs for the PD structure are 3054 ms and 2621 ms, respectively.

The results reveal that the items in the mismatch conditions are significantly slower. This is the expected direction for RTs but nevertheless a surprisingly significant result, considering that previous studies have not found an effect of context on the PD. In row three, we can see that the RTs are much slower when the given object is a pronoun. Again, as for the DOD, there is no interaction between condition and referring expression (RQ3).

From the results presented above it is clear that both givenness and referring expression have an effect on RTs. It also transpires that items with pronominal objects have faster RTs when compared to the DP items in DOD structures, but the opposite holds for the PD. It thus seems that DPs and pronouns affect the two alternates differently. Recall that we did not have any clear predictions for this research question, but the finding that DODs are much more likely to occur with a given object realized by a pronoun than PDs (Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Losongco, Wasow and Ginstrom2000, Kizach & Vikner Reference Kizach and Sten2018) suggests that these elements might be preferred with the DOD. Furthermore, given that previous research shows that the PD is insensitive to information structure (Clifton & Frazier Reference Clifton and Lyn2004, Brown et al. Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012, Kizach & Balling Reference Kizach and Laura2013) and that non-target structures yield longer RTs, we might expect faster RTs for this object order overall.

In order to investigate the effect of pronouns, we conducted pairwise comparisons on the logarithmic models presented for the RTs above (Tables 7 and 8, respectively), separately for DOD and PD. The pairwise comparisons compared the referring expressions in match and mismatch conditions in each structure. These are displayed in Tables 9 and 10.

Table 9. Pairwise comparisons of RTs of referring expressions in DOD.

Table 10. Pairwise comparisons of RTs of referring expressions in PD.

The analyses reveal that the RTs of DPs are significantly slower than that of pronouns in the DOD in both match and mismatch conditions; for the PDs, however, the RTs of DPs are faster than that of pronouns, but to a significant degree only within the mismatch conditions.

In order to check these further, we conducted two linear mixed effects regressions on DP and pronominal items separately, having the structure (DOD vs. PD) and context type (match vs. mismatch) as fixed effects. The intercept was set to the match condition with the DOD structure. The random effects were set as in the previous models, and the random intercept for participants was estimated at SD 0.2028, for test item at SD 0.1041 in the DP model (Table 11); the values were 0.2294 and 0.0991for the pronominal model (Table 12). The mean and median RT for the DP items were 3249.283 and 2757, whereas for the pronominal items these were 3124.893 and 2727.5.

Table 11. Linear mixed effects on the DP items (RE = referring expression).

Table 12. Linear mixed effects on the pronominal items (RE = referring expression).

The tables show that the RT of the PD is significantly faster than that of the DOD with DP items (Table 11). This is consistent with previous studies, as the PD generally has faster RTs. There is no interaction of structure and context which means that givenness has roughly the same effect on the two alternates. Surprisingly, the results reveal that the PD is significantly slower than the DOD in conditions with pronominal objects. This is a new finding since the previous studies testing RTs did not compare pronominality within the two alternates. This means that RTs of the PD is generally faster with DP objects, whereas the DOD benefits from pronominal objects. The possible reasons for this will be put forth in the discussion.

6. Discussion

In this paper, we have investigated to what extent the two alternate dative structures are sensitive to givenness in Norwegian. In what follows we will discuss three key findings that cumulatively answer our research questions.

6.1 Sensitivity to givenness

Previous studies have revealed that DODs are affected by givenness in Danish and English, and the same is clearly the case for Norwegian as well. Unlike other studies, we have also found givenness to affect PDs, since the items were more likely to be accepted with a given theme than with a given recipient (p < .001). DODs are more strongly affected than PDs, however, as there were significantly more items judged as ‘bad’ in the mismatch condition compared to the PD (Table 3 above). Furthermore, this rejection rate was more pronounced for pronominal objects than for DP objects, as indicated by an interaction effect between givenness and referring expression in these structures (DOD: p < .001/PD: p < .01).

As expected, DODs had slower RTs in mismatch conditions when compared to match conditions (p < .001). This was also true for the PDs (p < .01). Thus, the PD is sensitive to givenness in Norwegian (albeit less so than the DOD). This means that a givenness effect was observed both in the acceptability ratios (RQ1) and RTs (RQ2) in both alternates.

These results are consistent with the results of the Norwegian child language study reported in Anderssen et al. (Reference Anderssen, Rodina, Mykhaylyk and Fikkert2014), where a small group of adult controls in a production task used PDs in theme-given contexts 74% of the time and DODs in recipient-given contexts, 88% of the time, clearly indicating that the choice of word order is dependent on givenness.

In English and Danish, the lack of sensitivity to givenness in PDs has been attributed to this being the canonical structure (recall Section 2.1 above). In fact, in both Kizach & Balling (Reference Kizach and Laura2013) and Clifton & Frazier (Reference Clifton and Lyn2004), the new>given version of the PD was preferred (faster RTs and higher acceptability) when givenness was expressed only through definiteness marking. This result was significant in Clifton & Frazier (Reference Clifton and Lyn2004), while in Kizach & Balling (Reference Kizach and Laura2013), it was only approaching significance. In Clifton & Frazier’s (Reference Clifton and Lyn2004) second experiment, which included contexts, this preference was neutralised and there was no effect of givenness.

We have seen that there are many factors involved in determining object order in ditransitives and that these often align. In fact, double objects involve many different types of prominence hierarchies: a preference for given elements to precede new ones, animate referents to precede inanimate ones (Comrie Reference Comrie1989, Corbett Reference Corbett2000), recipients to precede themes (Givón Reference Givón1984, Bresnan & Kanerva Reference Bresnan and Kanerva1989, Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1992), and pronouns to precede DPs. The DOD represents the optimal alignment of all these factors when the given object precedes the new one and the given element is expressed by a pronoun, see Table 13. The PD, on the other hand, is always less optimal because the theme always precedes the recipient, and the inanimate referent typically precedes the animate one. As a consequence, when the given>new principle is obeyed, there is a conflict between the givenness hierarchy, on the one hand, and the animacy and the thematic role hierarchies, on the other.

Table 13. Alignment of various prominence hierarchies in the DOD and the PD, the properties that should come first due to harmonic alignment are expressed in boldface.

This inherent conflict between different types of prominence hierarchies with PDs might explain why there is a preference for the indefinite>definite order when contextual givenness is not included in the task in Clifton & Frazier (Reference Clifton and Lyn2004) and Kizach & Balling (Reference Kizach and Laura2013). In the absence of context, the order indefinite>definite aligns definiteness with both animacy and the recipient role, making this the most harmoniously aligned structure. When givenness is added as a factor, however, the order definite>indefinite aligns with givenness, making it more likely that this order will be preferred. If there is variation in how the relevant factors (givenness, thematic role, animacy) are weighted in different languages, this might explain why there is an effect of givenness (albeit small) in Norwegian but not in Danish and English. Indeed, this kind of variation has been shown for different varieties of English. For example, Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2003) shows that speakers of American English are affected by the length of the possessum in their choice of the Saxon genitive, while speakers of British English are not. Similarly, speakers of New Zealand English are more likely to use inanimate recipients in DODs than speakers of American English (Bresnan & Hay Reference Bresnan and Jennifer2008), and US speakers were more sensitive to the length of themes in the PDs than their Australian peers (Bresnan & Ford Reference Bresnan and Marilyn2010). If the explanation in terms of different hierarchies is correct, this means that subtle variations in experimental materials may result in different outcomes.

6.2 The effect of referring expression on acceptability

For RQ3, we predicted that the addition of pronominality would lead to a lower acceptance rate and longer RTs in the mismatch conditions because of the double violation of harmonic alignment. Our results indicate that this is indeed the case, at least for acceptability ratings, as an interaction was found between givenness and referring expression in both structures. Sentences in the mismatch condition with a pronominal object theme, i.e. Han ga en pasient den ‘He gave a patient it’ were rated as unacceptable in the majority of cases (56%), which is consistent with the claim that the equivalent structure is ungrammatical in American English (Larson Reference Larson1988, Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Losongco, Wasow and Ginstrom2000, Stephens Reference Stephens2010).Footnote 3

6.3 The effect of referring expression on structure

With the final research question (RQ4), we asked to what extent there is a general effect of referring expression on processing of the two alternates. To determine this, we compared the RTs of pronominal and DP objects and found that DODs are processed faster when the given object is a pronoun, while PDs have faster RTs with DPs, but only significantly so in the mismatch condition. Moreover, pronominal DODs have significantly faster RTs than pronominal PDs (p < .001), while the PDs have significantly faster RTs than the DODs when the given object is a DP (p < .001). This result strongly suggests that there is something like a pronominal bias in the DOD and a DP bias in the PD as far as processing is concerned.

Interestingly, the fastest mean RTs in the study come from match conditions in both structures: 2730 ms for theme-given DP objects in the PD, and 2811 ms for recipient-given pronominal object in the DOD. Similarly, the slowest recorded RTs were confined to the mismatch conditions, but again, the two structures differ with regard to which type of referring expression this applies to. For the DOD, structures with theme-given DP objects have the slowest RT (4048 ms). For PD, the slowest mean RT is 3319 ms and occurs with pronominal recipients. In fact, for the DOD, the match condition with DP objects is slower than the mismatch with pronominal object, while for the PD, the match condition with pronominal objects is slower than the mismatch with DPs objects (see Table 9). Thus, the PD has an RT advantage, but only when the given object is a DP.

So why is the DOD processed faster when it involves a pronoun, while the PD has faster RTs with DPs? Recent years have seen an upsurge of studies exploring how factors such as animacy, givenness and topicality influence processing, see e.g. Burmester et al. (Reference Burmester, Spalek and Wartenburger2014) and Hung & Schumacher (Reference Hung and Schumacher2014) and references therein. Such studies provide even more convincing evidence that elements that are more prominent according to various prominence hierarchies are more easily processed if they precede less prominent elements, in accordance with the original idea expressed by e.g. Clark & Haviland (Reference Clark and Haviland1977). To our knowledge, no study has so far considered potential differences between definite DPs and pronouns in terms of processing speed depending on the structures in which they occur. Recall that in Danish and English pronouns are used frequently in DOD structures, but rarely in PDs (Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Losongco, Wasow and Ginstrom2000, Kizach & Vikner Reference Kizach and Sten2018). We do not know what the situation is for Norwegian, but if similar distributions are attested, this might be a frequency effect. The question is whether this distribution is a reflection of deeper properties of the two structures. If so, this might be related to the clash in prominence between factors that are inherently prominent in DA structures, such as animacy and thematic role, on the one hand, and information structural factors such as givenness and pronominality, on the other (see Table 13). Even though previous studies have not tested pronominal objects, the findings in Clifton et al. (2004) support these observations partly, as they conclude that the DOD in general ‘was responded to more slowly and accepted less frequently’ than the PD in their study, which only tested DPs.

Another explanation is related to syntactic structure. In languages such as Norwegian, which do not have case marking, the PP clearly marks the recipient, ensuring that the theme (DP) and the recipient (PP) are differentially marked syntactically.Footnote 4 This also makes PDs more transparent interpretively, and might cause them to be processed faster. The DOD has no such syntactic marker, as the recipient and the theme are differentiated by their position only (and often animacy as well). Thus, using a pronominal referent to mark the previously encountered object might have a positive effect on processing and simultaneously distinguish between the two objects more clearly.

Moreover, as also indicated in Table 13, the first objects in ditransitive structures are different in other important respects. Even though both recipients and themes can be either animate or inanimate, the test items in this task had prototypical animacy (Velnić Reference Velnić2018): the recipient was animate (i.e. pasient ‘patient’), and the theme was inanimate (i.e. juice ‘juice’). As animate entities might be more likely to be expressed by a pronoun, animacy might also play a role. This factor has been attested as influential in the dative alternation in English (Bresnan et al. Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina and Baayen2007) and GermanFootnote 5 (Kempen & Harbusch Reference Kempen and Karin2004); moreover, animate referents are typically found in syntactically prominent positions and often referred to by pronouns (Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Losongco, Wasow and Ginstrom2000, Branigan, Pickering & Tanaka Reference Branigan, Pickering and Mikihiro2008). Thus, animacy might explain why DOD structures are processed faster with pronominal objects. However, recall the results from Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012) where both (DP) objects were animate: they revealed that the dispreference for the DOD in theme-given contexts is not due to the indefinite animate argument, as given>new structures in DODs were processed significantly faster even when both objects are animate (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Savova and Gibson2012).

7. Conclusion

This study has shown that the PD is sensitive to givenness in Norwegian, but less so than the DOD. Thus, the difference between the DOD and PD observed for English and Danish is to some extent also found in Norwegian. We propose that different alignments of the prominence hierarchies involved in the two structures explain the discrepancy in sensitivity to givenness in Norwegian, with a pragmatically appropriate DOD being the optimal alignment of all of them. This might also explain crosslinguistic differences, as various factors might not have the same weighting in different languages, see e.g. Bresnan & Ford (Reference Bresnan and Marilyn2010).

The current study is different from previous ones because it includes pronominal objects. Our results reveal that these elements had the expected effect on acceptability judgements, as givenness had a stronger effect on both DOD and PD structures involving pronominal objects. However, referring expression did not have the expected result on RTs in the sense that pragmatically inappropriate structures with pronominal objects did not consistently have longer RTs. Rather, including pronouns in the study revealed that the two dative alternates have different optimal referring expressions. PDs where the given object is realized by a pronoun have longer RTs than those involving DPs. For the DODs, the situation is the opposite; structures with pronouns have faster RTs. One possible explanation for this behaviour might be the frequency with which the two types of referring expressions are used in the two structures, which might cause prototypical structures to be processed faster.

Acknowledgements

We thank Björn Lundquist for his immense help with the statistical analysis, Isabel Nadine Jensen and Tor Håvard Solhaug for piloting the task, Anna Katharina Pilsbacher and Tor-Willy Knudsen for assisting with the scheduling of participants and the data collection. We would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers who have contributed in making this paper a better scientific study.

APPENDIX Target items divided per lists

Table A1. Test items in list A1.

Table A2. Test items in list A2.

Table A3. Test items in list B1.

Table A4. Test items in list B2.

Table A5. Grammatical/ungrammatical fillers.

Table A6. Pragmatic fillers.

Table A7. Transitive fillers (targets for another study).