The dhole Cuon alpinus is an Endangered social carnivore found in forested landscapes of South and South-east Asia. Historically widespread across Asia, the species' range has contracted by c. 80% (Wolf & Ripple, Reference Wolf and Ripple2017). The current distribution extends across most of South and South-east Asia and parts of China but is largely restricted to protected areas (Kamler et al., Reference Kamler, Songsasen, Jenks, Srivathsa, Sheng and Kunkel2015). The protected forest landscapes south of the River Ganges in India are a stronghold for the species (Acharya, Reference Acharya2007; Srivathsa et al., Reference Srivathsa, Karanth, Jathanna, Kumar and Karanth2014; Punjabi et al., Reference Punjabi, Edgaonkar, Srivathsa, Ashtaputre and Rao2017), with the largest dhole population (Kamler et al., Reference Kamler, Songsasen, Jenks, Srivathsa, Sheng and Kunkel2015). However, the species has undergone local extirpation across parts of its former range as a result of declines of prey species, loss of habitat and, potentially, disease (Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Nichols, Karanth, Hines and Christensen2010; Srivathsa et al., Reference Srivathsa, Karanth, Jathanna, Kumar and Karanth2014). Information on dholes in north-east India in particular is limited (Gopi et al., Reference Gopi, Lyngdoh and Selvan2010; Bashir et al., Reference Bashir, Bhattacharya, Poudyal, Roy and Sathyakumar2014; Lyngdoh et al., Reference Lyngdoh, Gopi, Selvan and Habib2014), despite the fact that this landscape shares continuous forest with Myanmar and South-east Asia, forming an important part of the species' global range.

Current knowledge of dholes in north-east India is restricted to landscapes north of the River Brahmaputra (Ginsberg & Macdonald, Reference Ginsberg and Macdonald1990). This is primarily because of the paucity of baseline ecological data from the region, given its undulating terrain, difficulty of access, wet climatic conditions, and socio-political insurgencies. Here we provide a compilation of dhole presence records from across north-east India using data extracted from multiple sources. Using data from camera-trap surveys we examine factors influencing fine-scale site-use by dholes in Dampa Tiger Reserve, Mizoram State. We discuss the implications of our results for dhole conservation in north-east India, where the focus of wildlife managers is directed mainly towards population recoveries of and local recolonization by the tiger Panthera tigris. We provide recommendations for management interventions that could facilitate conservation of dholes in this hitherto neglected landscape.

Dampa Tiger Reserve lies in the Indo-Myanmar Biodiversity Hotspot (Mittermeier et al., Reference Mittermeier, Robles-Gil, Hoffman, Pilgrim, Brooks and Mittermeier2004; Fig. 1). The reserve is contiguous with the Chittagong Hill Tract region of Bangladesh to the west. The core area of the Reserve covers 500 km2, and the multi-use buffer covers an area of 488 km2. The Lushai Hills traverse the reserve, with altitudes of 250–1,100 m. Mean annual rainfall is 2,000–2,500 mm (Islam & Rahmani, Reference Islam and Rahmani2004). The Reserve supports a high diversity of carnivores, including, in addition to the dhole, four species of felids and two species of ursids (Singh & Macdonald, Reference Singh and Macdonald2017). In this study we also recorded the elephant Elephas maximus, gaur Bos gaurus, sambar Rusa unicolor, red serow Capricornis rubidus, muntjac Muntiacus muntjak and wild pig Sus scrofa.

Fig. 1 North-east India, with Dampa Tiger Reserve in Mizoram and locations where the dhole Cuon alpinus has been recorded, with corresponding reliability scores (see text for details).

We compiled dhole presence records for nine north-eastern states (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tripura and West Bengal). We searched for records from 1990 onwards in newspaper reports, scientific articles, grey literature (including species checklists), and reports by forest department personnel, local informants and naturalists working in the region. For each record we noted the type of evidence (direct/indirect), date of sighting, administrative status of location (protected/non-protected), and source person or reference. We assigned reliability scores for each record (1–5; with 1 being most reliable, and 5 least reliable; Supplementary Table 1).

From December 2014 to March 2015, we deployed 79 pairs of Cuddeback Ambush IR camera traps (Model 1187; Cuddeback, De Pere, USA) across 80 km2 in the north-east of Dampa Tiger Reserve's core area. At each station we placed two cameras facing each other, c. 30 cm above the ground, on either side of forest trails or on riverbeds (Singh & Macdonald, Reference Singh and Macdonald2017). Mean inter-trap distance was 1.02 ± SD 0.33 km, with traps remaining active for an average of 64 days (range 3–91; Singh & Macdonald, Reference Singh and Macdonald2017). Although the stations were intended to photograph wild felids, they also photographed other carnivores. Dholes generally use forest trails and riverbeds for movement, marking territories and hunting, and our sampling design therefore incorporated areas used by the species.

We examined site-use patterns through an occupancy approach that accounted for imperfect detection (MacKenzie et al., Reference MacKenzie, Nichols, Lachman, Droege, Royle and Langtimm2002). We treated each station as a site, and each trap-day as an independent temporal replicate. During exploratory analyses we calculated Moran's I to check for spatial dependence of detections. Spatial dependence dropped beyond 2.3 km, with < 10% of distance-pairs falling within the first distance class (Supplementary Fig. 1). We considered this to be negligible with respect to the total number of trap stations and detections, and therefore treated each station as an independent site. The detection matrix therefore contained non-detections and detections (coded as 0 and 1, respectively) for 74 sites (data from five sites could not be retrieved), with a varying number of temporal replicates (3–91 days).

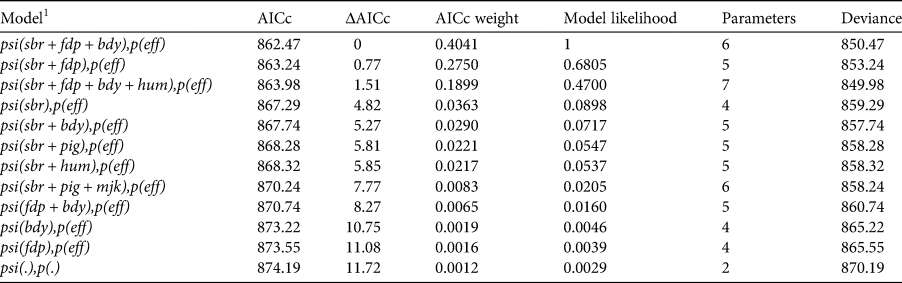

We used photo-capture frequencies of key prey species (sambar n = 236, muntjac n = 145, wild pig n = 92; predicted positive influence), distance to reserve boundary (predicted positive influence), photo-capture frequencies of forest department personnel (predicted positive influence) and photo-capture frequencies of other humans (predicted negative influence) as factors likely to influence site-use by dholes. We used trap effort (number of days a trap station was active) at each site as a covariate for detection probability, predicting that higher effort would translate to higher detectability. We tested singular and additive effects of the covariates, in which each represented an ecologically plausible hypothesis. Covariates were checked for cross-correlations and z-transformed prior to analyses. Models were ranked using Akaike information criterion corrected for small sample sizes (AICc; Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2002). Parameter estimation and model comparisons were calculated with PRESENCE 11.9 (Hines, Reference Hines2006).

We obtained presence records from 80 locations for 1990–2018, of which we considered 41 records from 2010–2018 with reliability scores of 1–3 (Supplementary Table 2). In the case of multiple records for the same site, we considered the most recent record with the highest reliability score. Most records were from Arunachal Pradesh (n = 14) and Assam (n = 8), with five records from Mizoram and Nagaland, four from West Bengal, three from Meghalaya and two from Sikkim. There were no recent records of dholes from Manipur and Tripura. A total of 5,033 camera trap-days in Dampa Tiger Reserve generated 500 photo-encounters of dholes, comprising 92 detections (one per 24 hour duration) across 33 sites. Using the top-ranked occupancy model (Table 1), we estimated mean site-use probability to be psi = 0.50 ± SE 0.03 (Fig. 2) and trap-level detectability to be P = 0.87 ± SE 0.02. The top three models received similar support based on AICc scores; we interpret the covariate effects on probability of site-use from these models. Sambar encounters, forest department personnel encounters and distance to reserve boundary had positive effects on probability of site-use by dholes (Table 2, Fig. 3). The slope coefficient associated with effort as a covariate for detectability was positive (mean = 0.23 ± SE 0.2).

Fig. 2 Estimates of probabilities of site-use (psi) by dholes in Dampa Tiger Reserve (Fig. 1) during December 2014–March 2015, based on camera-trap surveys and occupancy modelling.

Fig. 3 The effect of (a) sambar Rusa unicolor encounter frequency, (b) forest department staff encounter frequency, (c) distance to reserve boundary, and (d) other human encounter frequency on the probability of site-use by dholes in Dampa Tiger Reserve during December 2014–March 2015. Grey lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Table 1 The 11 top-ranked models (based on AICc scores) and the intercept-only model [psi(.), p(.)] for the probability of site-use by dholes in Dampa Tiger Reserve, Mizoram during December 2014–March 2015.

1 sbr, sambar encounter frequency; fdp, encounters of forest department personnel; bdy, distance to reserve boundary; eff, trap effort; hum, human activity; pig, wild pig encounter frequency; mjk, muntjac encounter frequency.

Table 2 Slope coefficient estimates ± SE for ecological and management covariates for the top three models (i.e. those with AICc scores < 2; Table 1) influencing site-use by dholes in Dampa Tiger Reserve, Mizoram during December 2014–March 2015.

1 sbr, sambar encounter frequency; fdp, encounters of forest department personnel; bdy, distance to reserve boundary; hum, human activity.

There are records of dholes across several areas of north-east India, including in unprotected areas. Previous global assessments indicated that the species faced near or complete local extirpation to the south of the River Brahmaputra (Ginsberg & Macdonald, Reference Ginsberg and Macdonald1990), contrary to our findings from Dampa Tiger Reserve. Corroborating current knowledge from other landscapes, we found a positive relationship between dhole site-use and sambar presence (Acharya, Reference Acharya2007; Andheria et al., Reference Andheria, Karanth and Kumar2007; Punjabi et al., Reference Punjabi, Edgaonkar, Srivathsa, Ashtaputre and Rao2017). Across their extant distribution, the range of dholes overlaps with that of tigers and leopards Panthera pardus. Wildlife managers in this region and elsewhere subscribe to unsubstantiated notions that dhole presence impedes colonization by tigers (P. Singh, pers. comm.), and consequently treat dholes as a problem species. On the contrary, tigers, leopards and dholes can exist provided protected areas support adequate densities of medium- to large-sized prey species (Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Srivathsa, Vasudev, Puri, Parameshwaran and Kumar2017).

Dampa Tiger Reserve is an important refuge for dholes in north-east India. It supports large tracts of inviolate protected spaces, and habitat connectivity with forested landscapes of the Chittagong Hill Tract region to the west, Mamit Forest Division to the north and Thorangtlang Wildlife Sanctuary to the south. Our camera-trap data indicate the presence of a guild of large herbivores in the Reserve, with at least five prey species of medium and large ungulate herbivores, facilitating the long-term persistence of dholes there. Our findings re-emphasize the importance of protected areas, which can serve as source sites for sustaining dhole populations across the region.

In areas with low prey densities, carnivores may have significant dependence on livestock (Khorozyan et al., Reference Khorozyan, Ghoddousi, Soofi and Waltert2015), and are consequently stigmatized. There is a strong negative relationship between dholes and livestock owners in Arunachal Pradesh (Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Datta and Madhusudan2004; Lyngdoh et al., Reference Lyngdoh, Gopi, Selvan and Habib2014) and other locations in the region. Given that dholes also occur outside protected areas in this region, they are potentially vulnerable to retributory killing. Negative interactions between people and dholes necessitate interventions to reduce poaching and facilitate recovery of prey, especially for species such as sambar that are impacted by low recovery rates following prolonged poaching (Steinmetz et al., Reference Steinmetz, Chutipong, Seuaturien, Chirngsaard and Khaengkhetkarn2009). Our findings need to be augmented with a systematic survey across the locations we identified, specifically in the states of Mizoram and Nagaland, to facilitate a pan-north-east India strategy for dhole conservation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pu Liandawla for granting us permission to work in Dampa Tiger Reserve, Pu Laltlanhlua and Pu Lalrinmawia for administrative and logistic support, Nandita Hazarika, Ecosystem-India, and Alexandra Zimmerman, WildCRU and Chester Zoo, for coordinating and administering this study, Assistant Conservator of Forest Pu Vanlalrema, Range Officer Pu Vanlalbera, D. Barman, K. Lalthanpuia and others for field support, the Robertson Foundation for a grant to DWM for funding the camera-trap study, and the Editor and two anonymous reviewers for feedback. AS was supported by the University of Florida, Wildlife Conservation Society's Christensen Conservation Leaders Scholarship, and Wildlife Conservation Network's Sidney Byers Fellowship.

Author contributions

Conception: PS, AS, DWM; data collection: PS; data analysis: PS, AS; writing: all authors, lead by PS.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. Data on presence records were obtained from published literature, media reports, and a network of researchers and naturalists who agreed to share information. All necessary research permits for camera-trap surveys were obtained from the State Forest Department of Mizoram.