Introduction

Protected areas are tools for conserving biodiversity but their objectives are often in conflict with other interests and values, thereby resulting in violence, loss of livelihoods, displacement of communities and resource degradation (Castro & Nielsen, Reference Castro and Nielsen2001; Treves & Karanth, Reference Treves and Karanth2003). Conflicts occur when two or more parties hold strong views over conservation objectives and one party tries to assert its interests at the expense of the other (Young et al., Reference Young, Marzano, White, McCracken, Redpath and Carss2010; Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013, Reference Redpath, Bhatia and Young2015). Such conflicts can occur when parties representing conservation interests try to impose restrictions on the use of forests and wildlife resources or displace and relocate local people from their abodes as a result of the establishment of protected areas (Vodouhe et al., Reference Vodouhe, Coulibaly, Adegbidi and Sinsin2010; Velded et al., Reference Velded, Jumane, Wapalila and Songorwa2012). Conflicts can also occur when protected wildlife has impacts on people and their activities, such as predating farm crops and livestock, resulting in retaliatory killings (Dickman, Reference Dickman2010; Mateo-Tomás et al., Reference Mateo-Tomás, Olea, Sánchez-Barbudo and Mateo2012).

Although in these circumstances conflicts may be inevitable, the challenge is to prevent such conflicts escalating, or to minimize their impacts (Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013). Since the 1980s, in response to such conflicts, there has been a move from conventional centralized approaches of protected area management to participatory and integrative approaches, including co-management and community-based natural resources management. Some scholars contend that co-management between local people, other stakeholders and state agencies offers substantial promise for conflict management (Butler, Reference Butler2011; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Ross and Coutts2016). These approaches are expected to foster community empowerment (Plummer et al., Reference Plummer, Crona, Armitage, Olsson, Tengö and Yudina2012), ensure inclusive decision making and legitimacy (Berkes, Reference Berkes2009; Sandström et al., Reference Sandström, Crona and Bodin2014), and lead to benefit sharing and, ultimately, livelihood enhancement (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shivakoti, Zhu and Maddox2012; Ming'ate et al., Reference Ming'ate, Rennie and Memon2014). Others have argued that co-management can strengthen the state's control over resources, leading to further marginalization of local communities (Castro & Nielsen, Reference Castro and Nielsen2001). Castro & Nielsen (Reference Castro and Nielsen2001) advocated that a clear assessment of the benefits and limitations of co-management as a mechanism for promoting conflict resolution, peacebuilding and sustainable development is necessary.

Studies of co-management have focused on the role and prospects of co-management in conflict resolution and management (e.g. Zachrisson & Lindahl, Reference Zachrisson and Lindahl2013; De Pourcq et al., Reference De Pourcq, Thomas, Arts, Vranckx, Léon-Sicard and Van Damme2015) but little is known about the actual contribution and influence of co-management in preventing or mitigating conflicts in protected areas. A key question is, to what extent does the involvement or otherwise of key stakeholders in protected area management affect the prevention and mitigation of conflicts? Here we focus on a case study in Ghana's largest national park, Mole National Park, which is currently implementing co-management programmes to promote stakeholder participation in Park management.

Specifically, we address three questions: (1) How do actors in the Park perceive conflicts between Park authorities and surrounding communities? (2) How have co-management initiatives helped to manage or prevent conflicts from escalating? (3) How can co-management initiatives be improved to enhance conflict management? Our study is based on the propositions that actors perceive conflicts when they are excluded from decision making regarding protected area management, and involvement (or exclusion) of key stakeholders, including surrounding communities, in the form of co-management has a significant impact on the prevention and mitigation of conflicts.

Conflict and conflict management: a theoretical framework

Conflicts have broadly been defined as differences in interests, goals or perceptions (Coser, Reference Coser1957; Pruitt et al., Reference Pruitt, Rubin and Kim2003). This definition has, however, been criticized for not distinguishing between conflicts and causal factors (Yasmi et al., Reference Yasmi, Schanz and Salim2006; De Pourcq et al., Reference De Pourcq, Thomas, Arts, Vranckx, Léon-Sicard and Van Damme2015) as differences are inevitable in almost all social encounters. Glasl's (Reference Glasl1999) impairment approach to conflict, however, provides clear criteria for distinguishing between conflict and non-conflict situations. Glasl (Reference Glasl1999) describes conflict as a situation in which an actor feels impairment from the behaviour of another actor because of differences in perceptions, emotions and interests. This approach notes three key elements that describe conflicts. Firstly, conflicts are attributed to two actors, the opponent and the proponent (Yasmi et al., Reference Yasmi, Schanz and Salim2006; Marfo & Schanz, Reference Marfo and Schanz2009). Secondly, the defining element of conflict, which is the key criterion to distinguish conflict situations from non-conflict situations, is the experience of an actor's behaviour as impairment. Thirdly, the approach distinguishes between the sources or causes of conflicts and the actual conflict situations. These three distinctions provide the framework for our study. Glasl (Reference Glasl1999) further provides a nine-stage conflict escalation model (Table 1) that describes the stages of a conflict, the threshold to the next stage, and strategies for de-escalation.

Table 1 A nine-stage model of conflict escalation (Glasl, Reference Glasl1999).

*In mediation a third party moderates between disputing parties, whereas in arbitration a third party listens to the concerns of both sides and reaches an independent decision.

Approaches to conflict management generally refer to a range of options for preventing the escalation of conflict (Yasmi, Reference Yasmi2007; Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013) but most do not provide a clear delineation of the stages of conflict management based on the level of escalation and resultant outcomes. Moore (Reference Moore2003), however, outlined a continuum of conflict management approaches ranging from informal, collaborative and private approaches that involve only the conflicting parties or a mediator, to more coercive actions that can involve violence (Fig. 1). The most appropriate and legitimate means of addressing a conflict depends on the situation and intensity or stage of the conflict (Glasl, Reference Glasl1999; Engel & Korf, Reference Engel and Korf2005). Moore's (Reference Moore2003) continuum of conflict management approaches reflects Glasl's escalation model. We therefore applied Glasl's impairment approach and conflict escalation model to define the conflict situation and stages of escalation, and Moore's (Reference Moore2003) conflict management strategies to analyse the contribution of co-management in prevention and mitigation of conflicts, to determine at which stages of conflict co-management is possible and can yield positive outcomes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Stages of conflict escalation and conflict management strategies (adapted from Glasl, Reference Glasl1999, and Moore, Reference Moore2003).

Study area

Forest and wildlife resources are the main source of livelihood for many rural people in Ghana. However, in the process of utilizing these resources they have severely depleted them. In 2000, to ameliorate this situation and to address the increasing conflicts between protected area management and surrounding communities, the Wildlife Division of the Forestry Commission commissioned a policy for Collaborative Community Based Wildlife Management. The aim was to ‘enable the devolution of management authority to defined user communities and encourage the participation of other stakeholders to ensure the conservation and a perpetual flow of optimum benefits to all segments of society’ (Forestry Commission of Ghana, 2000, p. 6). This policy culminated in two primary institutional mechanisms for implementing collaborative forest and wildlife management both within and outside protected areas: Protected Areas Management Advisory Units and Community Resource Management Areas. The latter provide a mechanism by which authority and responsibilities for wildlife are transferred from the Wildlife Division of the Forestry Commission to rural communities within the same socio-ecological landscape, who collaborate with other non-local stakeholders to achieve linked conservation and development goals and derive economic incentives through the promotion of community-based tourism, art and craft production, and promotion of alternative livelihood options such as beekeeping. Protected Areas Management Advisory Units serve as focal points in which protected area administrators and stakeholders, including local government, government agencies, NGOs and surrounding communities, come together to exchange ideas on natural resource management and to resolve any conflicts. All surrounding communities are part of a Protected Areas Management Advisory Unit and therefore benefit from its activities. On the other hand, only communities who have formed Community Resource Management Areas enjoy benefits accruing from them.

Our study focuses on the 4,577 km2 Mole National Park, which was gazetted as a National Park in 1971 and has had a turbulent history that involved the forced eviction of whole communities from within the Park (Forestry Commission of Ghana, 2011). The Park's enclosure of traditional hunting grounds, farmlands and sacred sites resulted in the loss of livelihoods and homes, fuelling resentment towards the Park's authorities. The turbulent history of the Park's establishment, its effects on the socio-economic well-being of c. 40,000 people and its present drive to curb depletion of forest and wildlife resources and encourage the participation of stakeholders in protected area management make it an ideal case study (Yin, Reference Yin2013).

Methods

Data collection

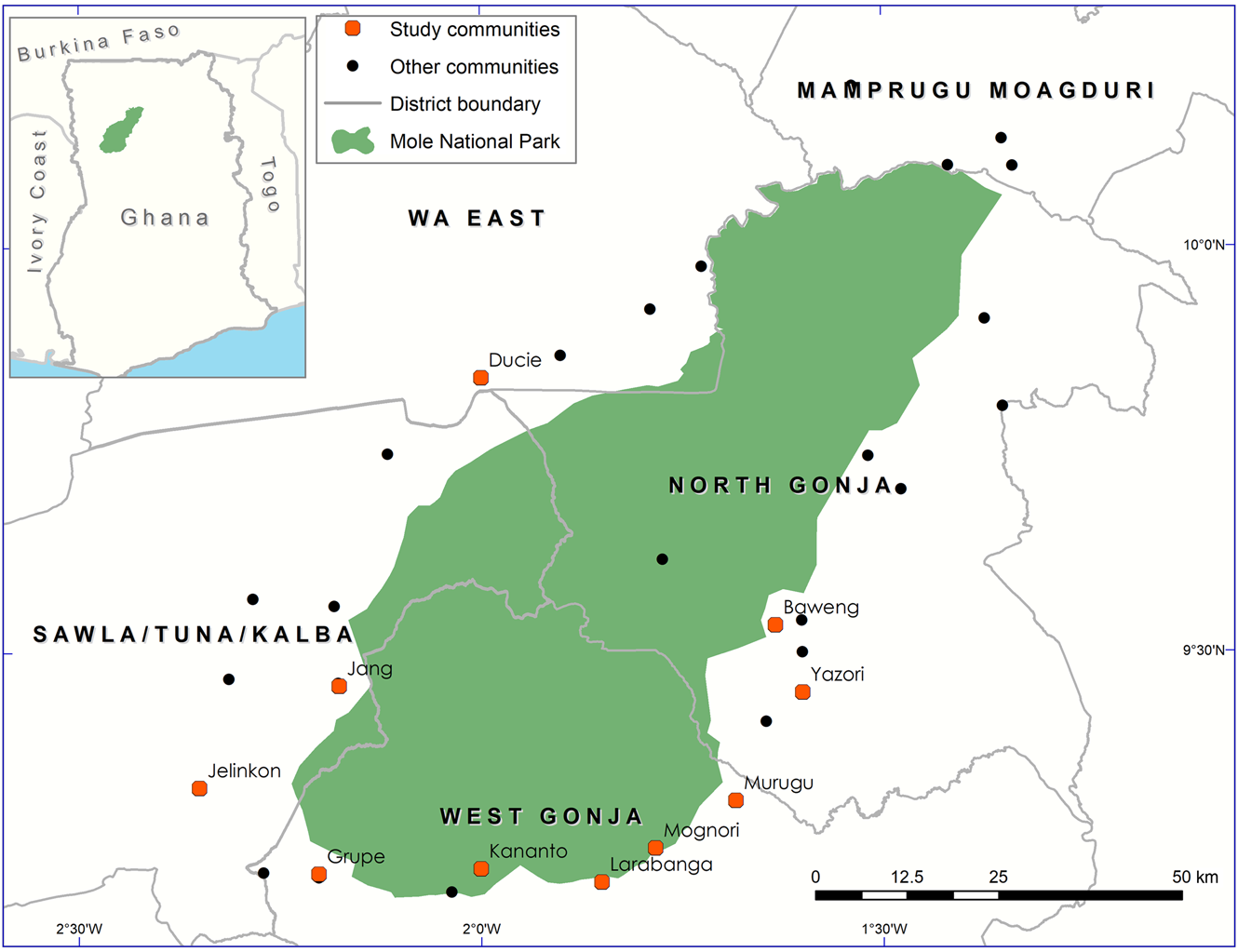

A case study approach was adopted because of its appropriateness for addressing either a descriptive question (what happened?) or an explanatory question (how or why did something happen?), and also because it enables the researcher to examine a ‘case’ in-depth within its ‘real-life’ context (Yin, Reference Yin2013, p. 16). Data were collected during October–December 2015. Of the 33 communities surrounding the Park (Fig. 2) 10 were selected, to provide a diverse range of cases (Table 2). A community in this context refers to a group of people who live within a defined geographical area, share the same values and customs, and are subject to a chief. Thus, communities were selected based on their proximity or remoteness to the Park, their ethnic background and the availability or non-availability of Community Resource Management Areas in the communities. The identification and selection of information-rich cases in qualitative research ensures that individuals or groups of individuals who are especially knowledgeable about or have an experience with a phenomenon of interest are selected (Creswell & Plano Clark, Reference Creswell and Plano Clark2011; Palinkas et al., Reference Palinkas, Horwitz, Green, Wisdom, Duan and Hoagwood2015).

Fig. 2 Mole National Park, showing the surrounding communities and study communities.

Table 2 Characteristics of the 10 selected study communities (Fig. 1).

We used focus group discussions, in-depth interviews and observations to ensure triangulation and validation of information from the various sources, as prescribed for case study research (Yin, Reference Yin2013). At least two focus groups were held in each community, with occupational and social groups who had an interest in the Park and were often in conflict with Park authorities, including seven with farmers, two with hunters, 10 with women engaged in agro-based small-scale industries, one with young people and three with the elderly. Focus groups are ideal for research relating to a group of people who share characteristics, such as occupation, and experience the same group norms, meanings and processes (Silverman, Reference Silverman2013). Focus groups comprised adults ≥ 18 years of age who resided in the communities. In the focus groups community members were invited to talk freely about actions of the managers of the Park that they perceived as an impairment or conflict and about the factors that led to conflicts, to describe the extent of local people's involvement in co-management (including the forms this involvement took and their roles and responsibilities in such arrangements), and how this co-management arrangement may have helped reduce incidents of conflict and how co-management could be improved to enhance conflict management.

In-depth interviews were also conducted with Tendanas (the local customary authority overlooking land issues in Northern Ghana), chiefs of the communities, local government representatives in the communities, Park officials and representatives of environmental NGOs working in the area. Participants were purposefully selected (Creswell & Plano Clark, Reference Creswell and Plano Clark2011). Tendanas and chiefs were selected as they are knowledgeable about the history, culture and values of the communities (Tonah, Reference Tonah2012). Environmental NGOs were selected to provide information on their role in facilitating co-management initiatives and the influence of these initiatives on conflict management. In addition, secondary data were collected from policy documents, Park management reports and constitutions of co-management boards, and from observations during our field work. Interview questions depended on the roles of the interviewees in co-management in the Park. Questions generally focused on individual roles, co-management processes, the contribution of co-management to reducing conflicts and how co-management could be improved to enhance conflict management. In-depth interviews were generally used as a follow up to focus group discussions: issues that were raised during the focus groups were probed further, for depth and details (Morgan, Reference Morgan1997).

Data analysis

In total, 26 focus groups were held and 22 interviews conducted. Focus groups and some interviews with local leaders were conducted in the native languages of the various ethnic groups of the participants, with the help of translators. These interviews and discussions were recorded, with the consent of all participants, and translated and transcribed into English. Focus groups lasted 35–45 minutes. The transcripts were analysed using an inductive approach in which we allowed the research findings to emerge from the frequent, dominant or significant themes inherent in the data (Thomas, Reference Thomas2006). Using Glasl's (Reference Glasl1999) definition of conflict and conflict escalation model and Moore's (Reference Moore2003) classification of conflict management strategies, we identified texts representing actions perceived as impairments, sources of impairment, impairment experienced, characteristics of conflict escalation and conflict management strategies, which we then coded.

Data obtained from secondary sources and observation were reviewed and analysed based on relevant themes such as co-management in the Park and the history of the study area. Connections were then drawn between the analysis of the focus groups and interviews and the secondary sources and observation data to arrive at the contributions of co-management in mitigating conflicts.

Results

Perception of conflicts

Actions that community members perceived as impairment, as articulated in the focus groups, primarily concerned their livelihoods, with problems such as loss of food crops, reduced incomes, food insecurity, increased poverty, less land for farming, and loss of raw materials to sustain livelihoods (Table 3). These impairments were blamed on unclear Park boundaries, overlapping land claims, need for income and an absence of a policy on compensation. Interviews with Park officials revealed four key behaviours of surrounding communities perceived as impairment to conservation and the Park's objectives (Table 4), mainly related to issues that threatened the destruction of forest and wildlife species and the degradation of the environment.

Table 3 Community perspectives of the actions or behaviours of Mole National Park officials perceived as impairment, sources of impairment, and impairment experienced.

Table 4 Park officials’ perspectives of actions or behaviours of surrounding communities perceived as impairment, sources of impairment, and impairment experienced.

Contribution of co-management to conflict prevention and management

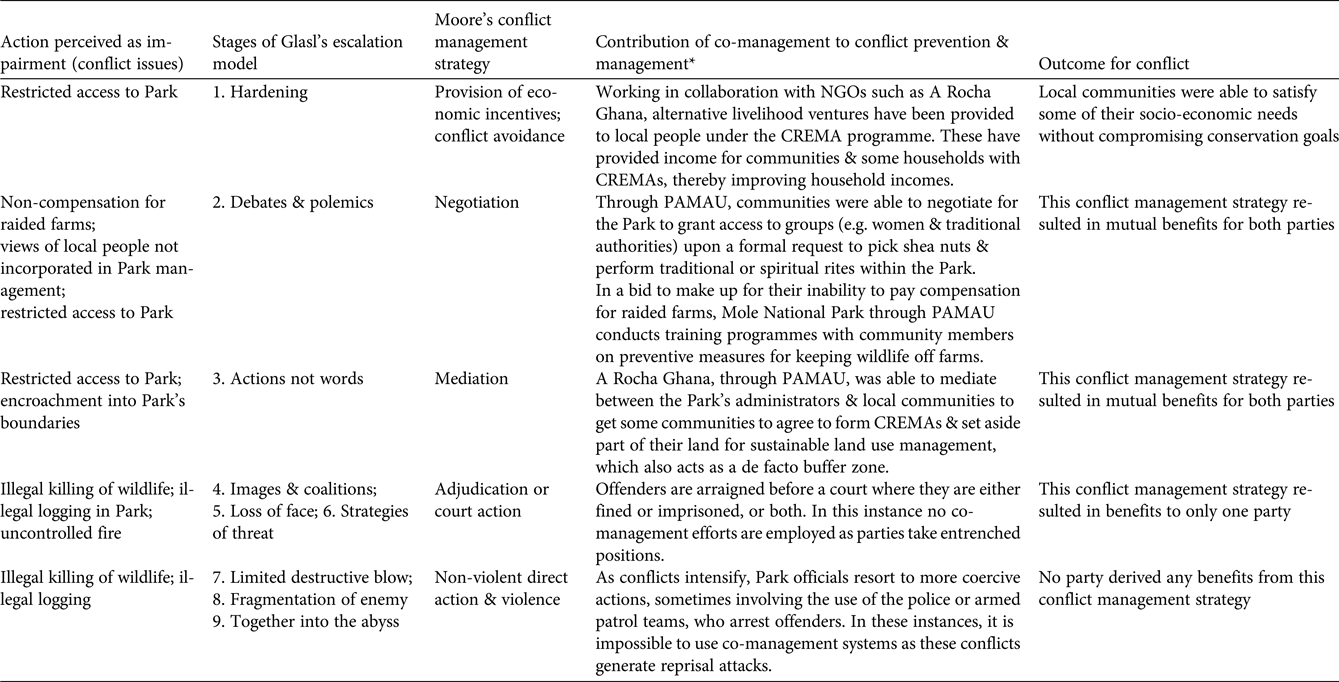

We categorized and analysed conflicts (perceived impairments) described by community members and Park officials according to the characteristics of the stages of Glasl's conflict escalation model. The stages of conflict escalation therefore do not necessarily represent the sequence in which the conflicts occurred. However, interviews with Park managers revealed that conflict management strategies were executed at the same time with all communities, which suggests that most conflicts might have occurred contemporaneously. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the conflicts differed, as communities without Community Resource Management Areas received no economic compensation for loss of their livelihoods and hence had negative attitudes towards Park authorities. Table 5 presents conflict situations, the stage of escalation of the conflict, conflict management strategies employed (Moore, Reference Moore2003) and how co-management contributes to managing conflicts in the Park. All of Moore's conflict management strategies are employed in the Park except arbitration. However, in addition to the strategies presented by Moore, we included provision of incentives, which was a key conflict management strategy employed in the Park. Using Glasl's conflict escalation model as an analytical tool, we found that characteristics described in the first, second and third stages of conflict were present in conflict over restricted access to the Park, non-compensation for raided farms, views of local people not incorporated in Park management, and encroachment into the Park boundary. Participants in focus groups and interviews described how their standpoints at these various stages of conflict clashed, yet the parties were not entrenched in their positions because of open dialogue and a commitment to resolve the conflicts. They further attested that conflict avoidance and the use of economic incentives were used as conflict management strategies in the first stage of conflicts. An NGO official remarked:

We realized that most of these conflicts are as a result of impacts on livelihoods, therefore conflict management should target the root cause, which is providing alternative livelihoods. In collaboration with Park management, we have provided alternative livelihood sources in the form of beekeeping and community-based tourism, which have provided income for households in those communities.

Table 5 Conflict management strategies, contribution of co-management to conflict prevention and management and conflict outcomes.

*CREMA, Community Resource Management Area; PAMAU, Protected Areas Management Advisory Unit.

For conflicts in the second stage, participants in focus groups and interviews described how such conflicts were managed through negotiations between the parties. A Park official stated:

In a bid to make up for our inability to pay compensation for raided farms, we have negotiated with community members whereby we offer them training on preventive measures of keeping wildlife from destroying their farms.

When negotiations failed, NGO officials from A Rocha Ghana served as mediators between the Park and local communities. A male farmer in Jelinkon said:

We have always been sceptical about the Park managers so when they brought the idea that we form Community Resource Management Areas and set aside part of our land for sustainable land use management, we thought it was another ploy to take more land from us and we refused until A Rocha officials convinced us to do so.

Conflict management strategies that involved open and transparent dialogue in the form of negotiation, mediation and economic incentives were deemed by interviewees to result in positive outcomes because they resulted in mutual benefits for both parties: local communities were able to satisfy some of their socio-economic needs without compromising conservation goals. In Mognori a woman remarked:

Through deliberative processes, the Park management now allows us to collect shea nuts or fuel wood from the Park. Our chiefs are also allowed to perform traditional rites inside the Park. These activities do not harm wildlife or the forest, so the Park management is happy and we are also happy about this development.

In situations where deliberative processes are not employed and dialogue breaks down because of mistrust between parties, conflict could escalate to the fourth, fifth and sixth stages (Glasl, Reference Glasl1999). This is because conflict tends to be about gaining the upper hand and threatening the opponent, to force them in the desired direction (Glasl, Reference Glasl1999; Moore, Reference Moore2003). This proved to be the case in Mole National Park, where interviews with Park managers revealed that when dialogue broke down, the Park recorded an increase in illegal activities as local people resorted to killing of wildlife, logging and uncontrolled bushfires in the Park. To address these problems Park management resorted to arrests and court actions, which often resulted in one party being aggrieved. This development further triggered conflicts to escalate to the seventh, eighth and ninth stages because of entrenched positions. Park officials resorted to more coercive actions, including the use of the police or armed patrol teams to force local people to conform to the Park's laws. In an interview a Park official lamented:

The local people are armed, therefore our Park rangers are also armed and we also use the police to be able to counter any attacks during patrols as such actions have resulted in deadly clashes in the past.

Although these strategies sometimes helped to reduce illegal activities inside the Park, they did not involve any co-management systems, as dialogue is almost impossible at this stage because of heightened tensions and loss of trust between parties.

Discussion

We found that the perception of conflict by surrounding communities was usually caused by an effect on local livelihoods, whereas Park administrators perceived conflict when they experienced impairment of conservation goals or a flouting of rules. This suggests that actors will react when they experience impairment in their well-being (e.g. livelihoods) or feel that their core values or interests, such as maintaining conservation goals or traditional livelihoods, are threatened. Conflicts over biodiversity often emerge from impacts on biodiversity, usually in response to an effect on local livelihoods or other triggers (Young et al., Reference Young, Marzano, White, McCracken, Redpath and Carss2010), but incompatible values and interests can further escalate such conflicts. For instance, in situations where community members’ interests, such as hunting, were clearly at variance with conservation goals, collaboration was impossible, as acceding to this interest would undermine conservation goals. Therefore, conflict escalation as a result of incompatible differences also resulted in the unwillingness of parties to consider a negotiated agreement (Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013; Holland, Reference Holland, Redpath, Gutierrez, Wood and Young2015).

Regarding our second research question, which sought to assess how co-management contributed to preventing conflicts from escalating, we found that co-management is able to contribute to conflict prevention and management in instances where dialogue between conflicting parties and third-party mediation are possible. This enables parties to openly discuss shared problems and agree on acceptable solutions (Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2013). However, the process of dialogue requires transparency and trust, without which conflicts could escalate to a higher stage (Ansell & Gash, Reference Ansell and Gash2008; Sandström et al., Reference Sandström, Crona and Bodin2014). Successful conflict management is based on the intensity or level of escalation of the conflict (Yasmi et al., Reference Yasmi, Schanz and Salim2006). It is therefore necessary to understand the context within which conflicts occur, as well as the dynamics of conflict escalation, to help anticipate the appropriate conflict management strategy. In the case of Mole National Park most conflicts concerned livelihoods, and therefore conflict management strategies such as provision of economic incentives proved successful. In consonance with other findings (e.g. Castro & Nielsen, Reference Castro and Nielsen2001; De Pourcq et al., Reference De Pourcq, Thomas, Arts, Vranckx, Léon-Sicard and Van Damme2015; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Ross and Coutts2016), we found that economic incentives were used both to encourage local people to participate in co-management arrangements and as a strategy for preventing and managing conflict. Community-based co-management initiatives that provided economic incentives were a key factor in variations among surrounding communities regarding the level of conflict escalation and the contribution of co-management in conflict mitigation. Communities that were not beneficiaries of community-based co-management expressed negative attitudes towards Park officials as these communities did not benefit from economic incentives such as alternative livelihoods and eco-tourism although their livelihoods had been affected by conservation. Although the Community Resource Management Areas initiative is a laudable venture, it has resulted in minimal economic effect in the area, as not all surrounding communities are beneficiaries because of inadequate funding by the state.

Regarding how co-management can be improved to enhance conflict management, we found that local knowledge, skills and practices were not incorporated into formal conflict management strategies. Park officials expressed fear that familiarity between local chiefs and local people could undermine the fight against illegal activities in the Park, but local chiefs believed they had better skills and knowledge to manage conflicts by virtue of the respect and status they enjoy in the communities. They further believed that traditional norms, taboos and the fear of ostracism or gossip were more effective in keeping people from engaging in illegal activities and managing conflicts than Park laws and imprisonment. Castro & Nielsen (Reference Castro and Nielsen2001) attested that one of the major benefits of co-management is the opportunity it offers for incorporating local knowledge, skills and practices into formal conflict management. Our interviews with stakeholders revealed that communities were represented on co-management boards as homogenous groups rather than as specific resource groups. This can overshadow specific needs of different segments of the communities, including farmers, hunters and women, who all have different interests in the use and management of the Park's resources (Neumann, Reference Neumann1997; Engel & Korf, Reference Engel and Korf2005). Park officials and NGO representatives, however, cited financial constraints for the inability to have all stakeholder groups from all communities represented on such boards.

Based on the two propositions of our study, we found that beyond their exclusion from decision making, actors perceived conflict when their socio-economic well-being (livelihoods and social needs) or core values and interests (conservation goals) were threatened. Secondly, the involvement of key stakeholders in the form of co-management helped to mitigate or prevent conflicts from escalating in the first to third stages through open and transparent dialogue in the form of negotiation, mediation and economic incentives.

We focused on assessing the contribution of co-management to conflict mitigation in the context of protected areas, and have shown that involving stakeholders, including surrounding communities, in co-management that involves open and transparent dialogue in the form of negotiation, mediation and economic incentives can influence successful conflict management. However, the success of co-management in preventing conflicts from escalating is dependent on a number of factors. Key among them is to first understand the context in which protected area conflicts occur, which includes determining which actions actors perceive to be impairments and what the sources of those impairments are. This is important in identifying what actors’ experienced impairments are, which then determines what form co-management should take to address those impairments. To ensure sustainable co-management it is important to incorporate local knowledge, ensure stakeholder representativeness and maintain dialogue among stakeholders while ensuring trust and transparency throughout the conflict management process.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written as part of the PhD study of OS, with a scholarship from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst and a travel grant from Müller-Fahnenberg-Stiftung. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and design: OS; data collection, analysis and interpretation: OS, US; writing and revision: OS, US.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx Code of Conduct. Formal approval and permits were sought from the Wildlife Division of the Forestry Commission of Ghana before commencement of the research. Free, prior and informed consent was sought from community members and other stakeholders before focus group discussions and interviews.