Introduction

Marine ecosystems are threatened by human activities on land and in the sea (Halpern et al., Reference Halpern, Frazier, Potapenko, Casey, Koenig and Longo2015). Coupled with growing human populations and economies, the main threats include overfishing (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Kirby, Berger, Bjorndal, Botsford and Bourque2001; Lotze et al., Reference Lotze, Lenihan, Bourque, Bradbury, Cooke and Kay2006; Worm et al., Reference Worm, Barbier, Beaumont, Duffy, Folke and Halpern2006, Reference Worm, Hilborn, Baum, Branch, Collie and Costello2009), pollution (Vitousek et al., Reference Vitousek, Mooney, Lubchenco and Melillo1997; Syvitski et al., Reference Syvitski, Vörösmarty, Kettner and Green2005), and habitat modification and degradation (Halpern et al., Reference Halpern, Walbridge, Selkoe, Kappel, Micheli and D'Agrosa2008, Reference Halpern, Frazier, Potapenko, Casey, Koenig and Longo2015; Burke et al., Reference Burke, Reytar, Spalding and Perry2011). Furthermore, climate change affects marine ecosystems through changes in sea level, aragonite concentrations, and temperature (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Kirby, Berger, Bjorndal, Botsford and Bourque2001; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Baird, Bellwood, Card, Connolly and Folke2003; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., Reference Hoegh-Guldberg, Mumby, Hooten, Steneck, Greenfield and Gomez2007). Marine protected areas are a key regional initiative that can help conserve marine biodiversity and sustain coastal resources (Gaines et al., Reference Gaines, White, Carr and Palumbi2010; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Graham, Jackson, Mumby and Steneck2010; Mumby & Harborne, Reference Mumby and Harborne2010; Edgar et al., Reference Edgar, Stuart-Smith, Willis, Kininmonth, Baker and Banks2014).

Given the growing threat to marine ecosystems, there is an increasing incentive to establish marine protected areas; for example, the Convention on Biological Diversity aims to represent 10% of marine habitats in protected areas by 2020 (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2011). As protected areas often constrain resource users such as fishers, establishing various types of zones can accommodate multiple conflicting and incompatible uses of the ocean (Crowder et al., Reference Crowder, Osherenko, Young, Airame, Norse and Baron2006; Yates et al., Reference Yates, Schoeman and Klein2015). Ocean zoning thus aims to regulate activities in time and space to achieve specific objectives for industries and biodiversity (Agardy, Reference Agardy2010).

Many approaches have been used to design zoning plans, from stakeholder- to software-driven processes. For example, stakeholder groups were responsible for developing networks of coastal marine protected areas in California (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Steinback, Scholz and Possingham2008; Gleason et al., Reference Gleason, McCreary, Miller-Henson, Ugoretz, Fox and Merrifield2010), and a national marine conservation strategy in the Marshall Islands (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Beger, McClennen, Ishoda and Edwards2011). In Papua New Guinea (Green et al., Reference Green, Smith, Lipsett-Moore, Groves, Peterson and Sheppard2009), Australia (Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Day, Lewis, Slegers, Kerrigan and Breen2005) and Indonesia (Grantham et al., Reference Grantham, Agostini, Wilson, Mangubhai, Hidayat and Muljadi2013), spatial planning software was used to identify priority areas for multiple human activities and biodiversity. Ideally, decision makers would utilize both stakeholder input and spatial planning software to identify zone placements to meet conservation and socio-economic objectives (Game et al., Reference Game, Lipsett-Moore, Hamilton, Peterson, Kereseka and Atu2011). However, there is limited guidance on how best to integrate these approaches to design a zoning plan for multiple uses. Few examples in the literature describe the challenges and opportunities associated with integrated approaches. Accessing lessons learnt from projects that pioneered such approaches remains a challenge. As an increasing number of nations embark on ocean zoning processes to conserve biodiversity and manage increasing economic activity, such guidance is required urgently to support effective decisions.

Here we describe the approach used to develop a zoning plan for Tun Mustapha Park in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo, in which the planning tool Marxan with Zones (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Ball, Stewart, Klein, Wilson and Steinback2009) was integrated with stakeholder consultation. Stakeholders included representatives from the government, academia, NGOs, and community members affected by the Park. One of the primary objectives of the plan was to meet basic representation targets for key marine habitats and species within the Park. We show how the representation of key marine habitats and species changed in each of three stages of the design process, as well as how evenly habitats and species are represented across each zone. We believe that lessons learned from our experience can guide decisions about how to zone for conservation and human uses elsewhere. In particular, we believe this study will be useful across the Coral Triangle, where an increasing number of zoning plans are underway, as the policy context and data limitations are similar.

Study area

Tun Mustapha Park is located in the northern region of Sabah. Prior to gazettement the region had no effective formal natural resource management plans, and laws regulating its resource use were not fully enforced. To address this the Sabah Government approved, in 2003, the intention to gazette the Park and the gazettement was finalized in May 2016. During this period the Park became part of two major initiatives: the Sulu Sulawesi Marine Ecoregion Programme and the Coral Triangle Initiative for Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security. The Initiative is a regional multilateral collaboration to manage coral reef resources. Tun Mustapha Park is one of the top priority sites within the region that will help fulfil multiple goals of the Initiative (Beger et al., Reference Beger, McGowan, Treml, Green, White and Wolff2015). The Park is globally significant for its marine life, with a rich diversity of coral reef, mangrove and seagrass habitats as well as several threatened species, including dugongs Dugong dugon, otters Lutra perspicillata, humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae, and marine turtles (Chelonia mydas, Eretmochelys imbricata, Lepidochelys olivacea; Dumaup et al., Reference Dumaup, Cola, Trono, Ingles, Miclat and Ibuna2003). The Park is home to > 187,000 people living in three administrative districts (Kudat, Pitas, Kota Marudu; Supplementary Fig. S1), almost half of which depend on marine resources for their livelihood and well-being (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2010; PE Research, 2011). Fishing is a primary economic activity in the region, and contributed 22% of total marine fisheries production in Sabah in 2008 (PE Research, 2011). Although trawl and purse seine fisheries are the largest fisheries in the region, the live reef fish trade, long-line and small-scale artisanal fisheries are significant for local livelihoods. Habitats and marine life are thus threatened by a suite of human activities, including overfishing, destructive fishing, unsustainable coastal land uses, and illegal harvesting of marine turtles and eggs (Jumin et al., Reference Jumin, Syed Hussein, Hoeksema and Wahid2013).

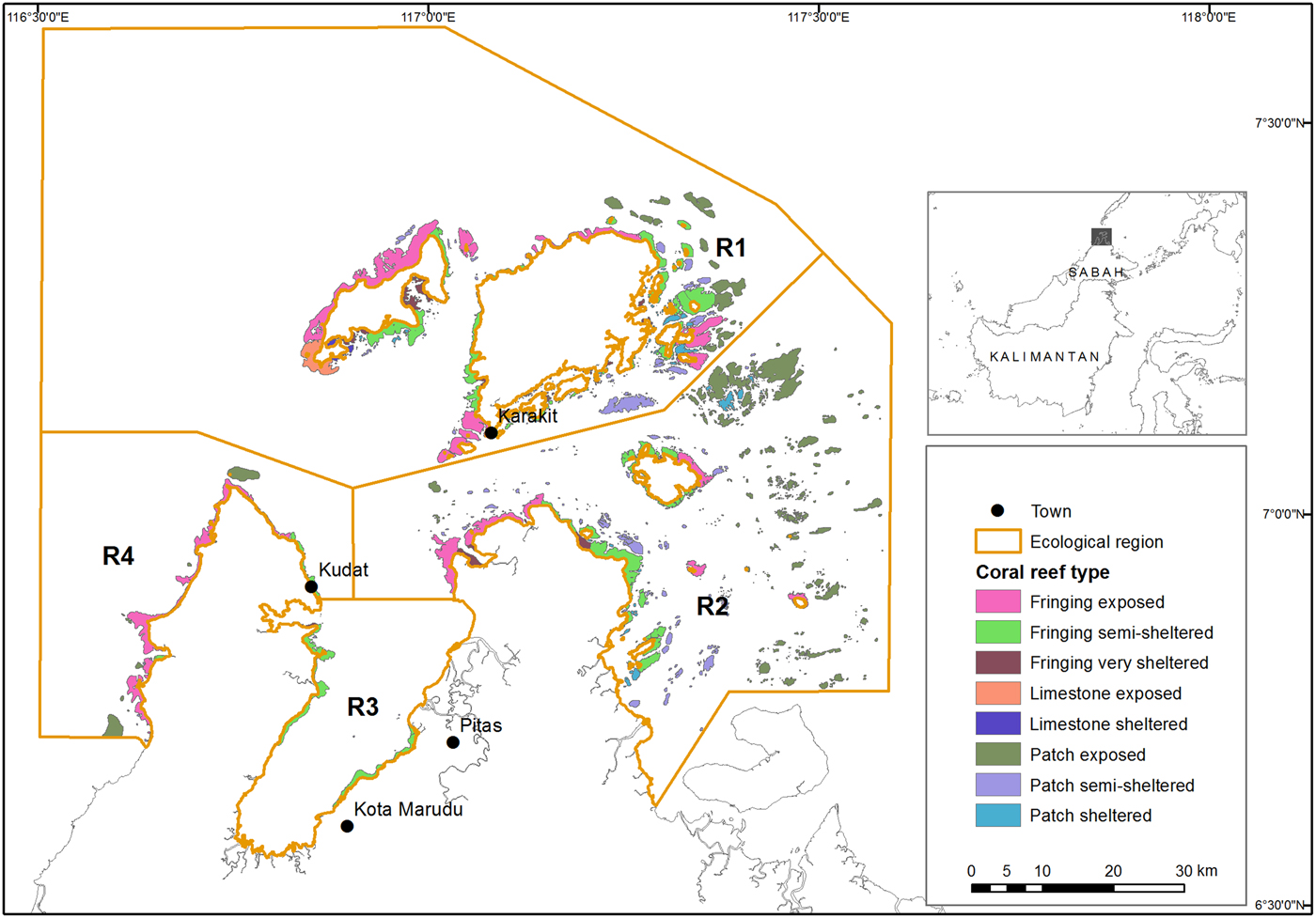

We categorized the Park into four ecological regions, based on geographical location, ocean currents and wind regimes that influence the development of coral reef ecosystems, and report our results according to these regions (Fig. 1). The planning area is 1.02 million ha, which includes areas three nautical miles (5.6 km) from the mainland and two nautical miles (3.7 km) from the islands within the Park. We excluded an area of c. 560 ha adjacent to Kudat Town because of heavy degradation and industrial development, including regional port and ferry terminals, and a landing jetty.

Fig. 1 Coral reef types and ecological regions (R1–R4) within Tun Mustapha Park, Sabah, Malaysia.

Methods

Zoning process

In 2003 the Sabah State Government approved the intention to gazette and zone the area for multiple uses, including conservation and fishing. The Sabah State Government has three objectives for Tun Mustapha Park: (1) eradicate poverty, (2) develop economic activities that are environmentally sustainable, and (3) conserve habitats and threatened species. In 2011 an Interim Steering Committee (henceforth the Committee) was established to manage and guide the development of an integrated management plan for the Park. The Committee comprises stakeholders representing the region's interests and is chaired by the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Environment. There are six technical working groups focused on various aspects of management, including a zoning working group, which facilitated all stages of the planning process described here, via review, feedback and endorsement of the final draft to the Committee. Stakeholder outreach was focused on the three objectives, with emphasis on how they could be achieved by a well-designed multiple-use marine protected area.

Prior to this zoning effort two major marine zones existed within the proposed boundary of the Park: a commercial fishing zone (> 3 nautical miles from the mainland and > 1 nautical mile from the islands) and a traditional fishing zone (< 3 nautical miles from the mainland and < 1 nautical mile from the islands). Both zones were insufficient to protect key habitats such as mangroves and coral reefs, existing laws were not fully enforced and as a result overfishing occurred and threatened species were killed. Potential new zone types were developed consultatively with key stakeholders from Sabah Parks, Department of Fisheries Sabah, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Land & Survey Department, Sabah Forestry Department, and Persatuan Pemilik Kapal Nelayan Kudat (Kudat Fishing Boat Owners’ Association) and other NGOs (Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Aliño, Atkinson, Belida, Binson and Campos2014). The new zone types determined for the Park were (1) a preservation zone, prohibiting all extractive activities; (2) a community use zone, in which non-destructive small-scale and traditional fishing activities are allowed and the nearby communities are encouraged to take part in the management of their own resources; (3) a multiple use zone, in which non-destructive and small-scale fishing activities as well as other sustainable development activities, such as tourism and recreation, are allowed; and (4) a commercial fishing zone, in which large-scale extractive fishing practices are allowed. Certain types of commercial fishing activities, such as long line (rawai) and recreational fishing, are also allowed in multiple use zones but not in the community use zone.

The primary four design principles considered in the zoning process were protection of key habitats in no-take areas, replication, representation and connectivity (Lee & Jumin, Reference Lee and Jumin2007; Green et al., Reference Green, Fernandes, Almany, Abesamis, McLeod and Aliño2014). Specifically, the representation goal was to ensure that all major habitats were included within no-take zones, and the replication goal was to ensure that each habitat was protected in multiple individual no-take zones. The zoning process was undertaken in three stages: prioritization, review and consultation (Fig. 2), each of which produced a proposed zoning map. The entire process involved academics, government and NGO representatives, and local communities. Here we describe each stage of the process and evaluate how well each resulting zoning plan achieved the conservation and socio-economic goals for the Park.

Fig. 2 The iterative planning process used for Tun Mustapha Park, Sabah, Malaysia (Fig. 1; refer to Supplementary Fig. S2 for the full zoning process).

Stage 1: prioritization using Marxan with Zones

We used the systematic conservation planning software Marxan with Zones (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Ball, Stewart, Klein, Wilson and Steinback2009) in the creation of multiple use zoning plans to ensure a repeatable, transparent and scientifically credible methodology (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Wilson, Watts, Stein, Carwardine, Mackey and Possingham2009). We identified priority areas for three zones: (1) preservation, (2) community use, and (3) multiple use. We did not include a zone for commercial fishing activities (i.e. trawling and purse seine gear). Rather, the commercial fishing zone was restricted to > 3 nautical miles from the mainland, which is the legal limit for commercial fishing activity in Sabah. However, this limit is not strictly enforced, and commercial fishing occurs closer to shore; a problem that will be addressed when the zoning plan is implemented.

For each zone Marxan with Zones requires two types of information: (1) how much and what type of features (e.g. habitat, distribution, fishing grounds) should be included in each zone, and (2) the cost of implementing the zone.

We targeted 15 conservation features (habitats and species) and two socio-economic features (fishing grounds and historical sites) in each of the four ecological regions for inclusion in preservation and community use zones (Table 1; Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Aliño, Atkinson, Belida, Binson and Campos2014). We set a target for each feature in each zone to address the principle of replication, which helps to ensure the zoning plan is resilient to catastrophic events (Green et al., Reference Green, Smith, Lipsett-Moore, Groves, Peterson and Sheppard2009, Reference Green, Fernandes, Almany, Abesamis, McLeod and Aliño2014). A minimum of 30% representation of habitats and species was set, in line with general recommendations from conservation science (Bohnsack et al., Reference Bohnsack, Causey, Crosby, Griffis, Hixon and Hourigan2000; O'Leary et al., Reference O'Leary, Winther-Janson, Bainbridge, Aitken, Hawkins and Roberts2016). This is higher than the 20% target set for the broader Coral Triangle (White et al., Reference White, Aliño, Cros, Fatan, Green and Teoh2014) but is justified by the prevailing threats of unsustainable fishing practices, such as dynamite and cyanide fishing. The Balambangan Island caves and historical sites were fixed as targets to protect their unique status (Lee & Jumin, Reference Lee and Jumin2007).

Table 1 Representation targets for conservation and socio-economic features for preservation, community use, and multiple use zones in Tun Mustapha Park, Sabah, Malaysia (Figs 1 & 3).

The coral reefs were divided into eight distinct types on the basis of a rapid morphological assessment of the Park's reef area, combining reef data from Zulkafly et al. (Reference Zulkafly, Magupin and Jumin2011) and UNEP-WCMC et al. (2010). Each reef type represents different reef assemblages based on the general influence of wind and ocean current exposure. Mangrove data were sourced from remotely sensed images from the SPOT-5 satellite, from 2006. Turtle nesting and feeding grounds, dugong habitat, and traditional fishing grounds were mapped using data from a community survey conducted during 2006–2007 by WWF-Malaysia and Sabah Parks (Jumin et al., Reference Jumin, Magupin and Kassem2012). The survey team visited 58 villages, interviewed > 500 people, using a structured questionnaire, and conducted discussions and mapping with > 1,500 local community members.

Many of the Park's communities depend on fisheries for subsistence and livelihoods, and therefore we aimed to minimize the impact of preservation zones on these communities. We developed a proxy of opportunity cost that was a function of distance from fishing villages (the closer to the village, the higher the cost) and important fishing grounds (higher cost where important fishing grounds existed). Furthermore, we targeted traditional fishing grounds in the community use and multiple use zones where traditional fishing is allowed. Distance from the village was used as the management cost for the community use zone: the further an area is from a village, the more costly it will be for the community to manage the area. As a cost is required for each zone, we defined the cost in the multiple use zones as the area of the planning unit; this essentially identifies the smallest area possible that achieves the conservation and socio-economic targets. We constrained Marxan with Zones to ensure that some of the preservation zones were adjacent to community use zones so that communities could benefit from the spillover of adult fish from the preservation zone.

Stage 2: review and enforceability assessment by Sabah Parks

The Marxan with Zones planning stage produced several zoning solutions that met the Park's conservation and socio-economic targets. As the analysis is based on a grid of small planning units, the boundaries of the zones are jagged and realistically cannot be enforced. Thus, the best solution Marxan with Zones map (Fig. 3a) was submitted to Sabah Parks to assess in terms of enforceability. Based on this map, Sabah Parks identified general areas for each zone, using the map as a guide to refine zone boundaries. This produced the first draft zoning plan that was endorsed by the Committee for stakeholder consultation (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3 The evolution of the zoning plan for Tun Mustapha Park through each stage of the planning process: (a) prioritization: best solution from Marxan with Zones results; (b) review: draft zoning plan endorsed by the Tun Mustapha Park Interim Steering Committee; and (c) consultation: revised zoning plan incorporating feedback from the stakeholder consultation.

Stage 3: stakeholder consultation

The stakeholder consultation was conducted by Sabah Parks, with support from WWF-Malaysia, Department of Fisheries Sabah, and Universiti Malaysia Sabah. Facilitators with in-depth knowledge of the Park, its stakeholders and their languages conducted consultations for feedback on the draft zoning plan produced in Stage 2, targeting three main stakeholder groups: local coastal communities, the private sector, in particular commercial fishers, and government agencies. Consultations were conducted in two steps, taking accessibility and efficiency of information dissemination into consideration, as well as the role and influence of the stakeholders in the decision making process. The first step involved discussions with district officers, briefing during District Offices Development Committee meetings (Pitas and Kota Marudu), an exhibition at the annual Kota Marudu Corn Festival, pilot testing on Banggi Island, where community leaders and members of the communities were invited to the district office of Banggi for presentations about the zoning process, and early ground surveys (Pitas, Kudat, Banggi, Matunggong). During the ground surveys facilitators visited at least 134 coastal communities/villages and the commercial fishing group based in Kudat, to inform community groups about the proposed plans, and to establish contact with village heads to assist with information dissemination for the second step.

The second step of the consultations involved the use of a semi-structured questionnaire as a tool for systematic capture of stakeholder feedback on the draft zoning plan, including direct input to the draft zoning map attached to the questionnaire. There were 1,017 respondents from the coastal villages (72% of targeted respondents) and 18 from the commercial fishing group (75% of targeted respondents).

Subsequent to the consultation with the coastal communities and the private sector, consultations were conducted with the district offices of Pitas, Kota Marudu, Kudat and the sub-district of Banggi, presenting the outcome of the previous consultations. Feedback from the stakeholders was incorporated into the draft zoning plan and, when necessary, follow-up consultations with specific stakeholders were undertaken to reach a consensus on their input to the zoning plan. The consultations resulted in a third zoning plan (Fig. 3c).

Evaluation of zoning maps produced in each planning stage

For each stage of the zoning process we calculated the amount of each conservation feature represented in each zone by region (Fig. 4). We also used an additional metric to illustrate how evenly the habitats were represented within each zone. This metric is a modification of the Gini coefficient (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Pressey, Fuller, Segan, McDonald-Madden and Possingham2011), which is widely used in economics as a measure of income equality. Here we used it to quantify the evenness of habitat representation within each zone for each planning stage. We modified the coefficient so that a value of 1 indicates perfect evenness across conservation features, and values closer to 0 indicate uneven representation. We also capped the coefficient, so that 30% protection was considered to be the maximum. For simplicity in the evaluation, we aggregated the coral reef types and report representation of coral reef habitat as a whole.

Fig. 4 Percentage allocation of conservation features to each zone (multiple use, community use, preservation) across planning stages for each of the four ecological regions in Tun Mustapha Park, Sabah, Malaysia. The target for the preservation zone was 30% per feature.

Results

The zoning plan resulting from Stage 1 (Marxan with Zones prioritization) achieved all conservation targets (Table 2). Stage 1 met the design principles for the preservation zones, representation of features and replication of features across regions. We found an even representation of features in the preservation zones, and an unequal representation of features in the other two zones (Table 2).

Table 2 Modified Gini coefficients for each of the three stages of the zoning process for Tun Mustapha Park, Sabah, Malaysia (Fig. 3), indicating habitat representation within each zone. Higher values indicate a more even representation of habitats/features.

In Stage 2 Sabah Parks altered the zone boundaries. This process maintained the 30% habitat targets achieved for Region 1 and Region 2 but did not maintain the 30% targets for coral reefs and seagrass in Region 3 or for seagrass and turtle nesting in Region 4 (Fig. 4). The Gini coefficient indicated reduced evenness in representation of features in preservation zones across the Park (Table 2). The draft zoning map from this stage produced large coastal preservation zones, particularly around Banggi Island, driven by the desire to protect important coastal habitats such as seagrass and mangroves (Fig. 3b).

In Stage 3 the stakeholder consultation process produced a result that reflects the general preference of stakeholders for more area assigned to community use and less for preservation. No 30% targets were achieved in Regions 1, 2 or 3. In these regions some features still achieved some inclusion in preservation areas (corals, dugong), but in Region 3 only 6% of corals were represented, and none of the estuary, mangrove or seagrass features (Fig. 4). The 30% targets for coral reefs and turtle habitat were achieved for Region 4 (Fig. 4). Stakeholders' preference to have preservation zones located away from their villages contributed to the lack of coastal habitats in the preservation zone. In some cases stakeholders recommended relocation of a preservation zone to areas that do not contain conservation features or important habitats. Some governmental decisions made during this process also contributed to the target shortfall, including excluding coastal land area and mangrove forest reserves from the Park boundary, and amending the outer boundary in some regions (Fig. 3c). This development equates to a change in management objectives during the process, where stakeholders decided that some nearshore habitats could not be represented, given their socio-economic and political needs.

Changing conservation objectives to accommodate economic and political realities is common (Sale et al., Reference Sale, Agardy, Ainsworth, Feist, Bell and Christie2014; Gormley et al., Reference Gormley, Hull, Porter, Bell and Sanderson2015; Goldsmith et al., Reference Goldsmith, Granek, Lubitow and Papenfus2016) but it compromises management outcomes and the livelihoods of people who depend on sustainable resource use. For example, many important fisheries species that are well protected on coral reefs require nursery habitat in seagrasses and mangroves (Olds et al., Reference Olds, Connolly, Pitt and Maxwell2012), which remain unprotected.

The biggest change was evident in Region 3. After the stakeholder process the coastal boundary of the Park was altered significantly; in some areas it was moved to 500 m away from the coastline, and the total area of the Park was reduced. Additionally, coastal habitats such as mangroves, seagrass and turtle nesting areas were excluded from the Park. As in Region 3, mangroves are not represented within the Park in Region 4, although some mangrove areas are protected by forestry management regulations (Boon & Beger, Reference Boon and Beger2016). The changes in the Park and zone boundaries reduced the Gini coefficient for the preservation zone but increased it slightly for the community use zone (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S3).

Discussion

The establishment of Tun Mustapha Park as a multiple use park under IUCN Category VI (Protected Area with Sustainable Use of Natural Resources) is the first of its kind to be established in Malaysia, and the first under the Coral Triangle Initiative (Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Aliño, Atkinson, Belida, Binson and Campos2014; Beger et al., Reference Beger, McGowan, Treml, Green, White and Wolff2015). We believe the Park makes substantial progress towards the protection of biodiversity and the ecosystem services it provides to the local communities. The planning process began with the approval of the intention to gazette the Park by the Sabah State Government in 2003, and spanned more than a decade and included the establishment of a management plan and the design of the Park zoning plan. However, it was not a perfect planning process and we focus the discussion on the challenges and lessons learned. Our aim is to assist other integrated planning processes within the Coral Triangle, and elsewhere, to establish marine protected areas.

Our evaluation shows that the conservation targets were substantially compromised in Stage 3 of the planning process, during the stakeholder consultations, when areas near the coastline were excluded from the Park and the outer boundary of the Park was reduced. These modifications reflect the concerns of the stakeholders, including local communities, government agencies, and industries (e.g. commercial fishing), who thought that they would not have access to natural resources once the zones were established. These concerns are, in part, attributable to the perception that the law under which the Park was established (Sabah Parks Enactment 1984) is focused on protecting biodiversity and does not allow for extractive activities, such as fishing. This perception arose because most parks established under this law are no-take state parks (established as IUCN category II) that allow only non-extractive recreational activities. However, as demonstrated with Tun Mustapha Park, special provisions can be made to allow for the establishment of multiple use parks (IUCN category VI). Educating stakeholders on the benefits of no-take areas to fisheries and food security, as well as clear communication of the special provisions of law, might have prevented some of the changes that occurred in Stage 3.

The reduction of the Park's outer boundary in Stage 3 reflects concerns of government agencies. In Sabah different government agencies have jurisdiction over different habitats important for marine biodiversity (e.g. mangroves, estuaries, turtle nesting areas). The Parks Enactment law does not allow for collaborative management, and the sole mandate of management belongs to the Sabah Parks Board of Trustees for a period of 99 years (Thandauthapany, Reference Thandauthapany2008). The lack of regulatory support for collaborative management contributed to the doubts of other government agencies that the Park could be managed successfully by multiple agencies. Consequently, government agencies preferred to maintain current management practices. For example, the Forestry Department requested that mangrove forest reserves remain under their management, and the District Offices requested the exclusion of some coastal area from the Park for development purposes (Binson, Reference Binson2014). Excluding these areas may influence the effectiveness of the Park in terms of marine resource management and biodiversity conservation. Most mangrove areas that are important for fish breeding will remain as mangrove forest reserves under the management of the Forestry Department, which does not regulate fishing activities, and turtle nesting beaches will remain as state land under the management of the Land Office, and will be subject to development. Overall, the exclusions reduced the total area gazetted under Tun Mustapha Park from the proposed 1.2 million ha to 898,762 ha (Warta Kerajaan Negeri Sabah, 2014).

We believe that if stakeholders had been involved earlier in the planning process the resulting zoning plan would have yielded better protection for biodiversity. Collective decision making on critical issues such as the park boundary, conservation objectives, features to be protected and their conservation targets, and the types of zones is a crucial step in conservation planning and the success of conservation plans (Margules & Pressey, Reference Margules and Pressey2000; Carwardine et al., Reference Carwardine, Klein, Wilson, Pressey and Possingham2009; Watts et al., Reference Watts, Ball, Stewart, Klein, Wilson and Steinback2009). Although the benefits of involving stakeholders at the beginning of the planning process are well known (Pollnac & Crawford, Reference Pollnac and Crawford2000; Beger et al., Reference Beger, Harborne, Dacles, Solandt and Ledesma2004; Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Day, Lewis, Slegers, Kerrigan and Breen2005; Crawford et al., Reference Crawford, Kasmidi, Korompis and Pollnac2006; Gaymer et al., Reference Gaymer, Stadel, Ban, Cárcamo, Ierna and Lieberknecht2014), inadequate resources delayed the consultation process until funding from the USAID Coral Triangle Support Partnership could be secured in 2010, facilitating a focused and structured effort to bring about the zoning and design of Tun Mustapha Park. This effort commenced with the establishment of the Interim Steering Committee in January 2011.

The delay led to other, not yet mentioned, challenging negotiations during stakeholder consultation in Stage 3. Several government agencies requested that new areas for commercial fisheries, aquaculture and socio-economic development be identified. Stakeholders in the trawl fishery were concerned that the exclusion of trawl fishing from multiple use zones would make their fishery unprofitable. Many of the trawl operators have to service significant loans taken out to buy boats and gear, which they feel they will not be able to repay if spatial restrictions are placed on their fishing effort (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Daw and McClanahan2009; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Travis and Dasgupta2011; Cinner, Reference Cinner2011; McNally et al., Reference McNally, Uchida and Gold2011). In line with institutional and legal support, adequate funding of the process over multiple years is vital to maintain momentum and to achieve stakeholder buy-in throughout the process.

Important hurdles tackled during the planning process arose from realities and perceptions of the legislation relevant to Malaysian marine parks. The Sabah Parks Enactment is perceived to be a strong legislation that does not allow for multiple use and collaboratively managed parks. We found that a legal framework that allows for the implementation of a conservation planning process geared towards multiple use and collaborative management would ensure commitment and foster confidence among the stakeholders involved in the process.

A decision support tool such as Marxan with Zones is useful because it translates the planning goals into spatial maps and provides several zoning options for consideration by stakeholders. In the development of a zoning plan for Tun Mustapha Park only one zoning map was given to Sabah Parks (Stage 2) for consideration. The decision to use only the best option produced by the Marxan with Zones analysis was based on the desire to keep communications with stakeholders simple, rapid and less technical. However, this was a mistake and we learnt that a number of different zoning plans should have been submitted to demonstrate that there are multiple ways to achieve the desired goals (Game et al., Reference Game, Lipsett-Moore, Hamilton, Peterson, Kereseka and Atu2011; Linke et al., Reference Linke, Watts, Stewart and Possingham2011).

The use of a planning tool and the associated internal learning processes of the implementing agencies were a novel step for Malaysian national parks planning. Many marine protected areas worldwide are planned without the use of decision support tools but although there are many valid planning approaches, decision support tools ensure that resulting plans achieve goals efficiently (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Steinback, Scholz and Possingham2008). Furthermore, they identify places that are required to achieve goals and places that are not needed to achieve goals, and provide stakeholders with alternatives for achieving their goals. Marxan with Zones was chosen because Sabah Parks and WWF-Malaysia required a decision support tool that was transparent, repeatable and could directly identify areas required for various management types (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Ball, Stewart, Klein, Wilson and Steinback2009; Game et al., Reference Game, Lipsett-Moore, Hamilton, Peterson, Kereseka and Atu2011). Marxan with Zones produces multiple options for decision making and informed selection of zones that can serve to guide an iterative decision process in stakeholder consultations. However, because of the need to reach a large number of stakeholders rapidly, the approach used in Tun Mustapha Park was to focus on the best solution produced by Marxan with Zones, which facilitated direct input from stakeholders into the Marxan design. Although this approach is flawed, by using Marxan with Zones the zoning team could assess whether conservation targets had been achieved and provide recommendations where critical areas needed to be included in the zoning plan.

The use of Marxan with Zones was challenging because it was new to most people involved in the zoning process. WWF and Sabah Parks staff invested considerable time in learning and understanding how to use the software. Although the software itself is relatively simple to use, it requires a sophisticated understanding of the principles of systematic conservation planning, as well as spatial analysis skills. We learned that understanding the basic guiding principles of systematic conservation planning and the socio-economic benefits of marine protected areas is perhaps more fundamental compared to understanding the mechanics of a decision support tool, as such technical expertise can be sourced externally. This type of education requires long-term commitment and ideally would start in university environmental programmes.

Future planning processes would benefit from explicit consideration of social implications, such as poverty traps, in planning tools. For instance, social equity is an important consideration in trading off conservation, cost and equity outcomes in reserve design (Agardy, Reference Agardy, Sinclair and Valdimarsson2003; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Travis and Dasgupta2011; Halpern et al., Reference Halpern, Klein, Brown, Beger, Grantham and Mangubhai2013). Although poverty traps were not considered explicitly in the tools used for the Tun Mustapha Park planning process, the process has helped to start discussions between fishers and the government. These discussions have brought poverty traps to the government's attention and it is seeking solutions, although implementation (e.g. trawler buy-back) is hindered by inadequate funding.

Zoning the ocean is one of many interventions used to manage natural resources. There are other effective tools that can be used either in isolation or in conjunction with ocean zoning, including various fisheries management regimes (e.g. quotas, gear restrictions; Day & Dobbs, Reference Day and Dobbs2013; Costello et al., Reference Costello, Ovando, Clavelle, Strauss, Hilborn and Melnychuk2016; Hilborn, Reference Hilborn2016). The designing of the zoning plan described here is part of the overall initiative to develop an integrated management plan for the Park. We hope that the lessons from this zoning process will provide guidance for implementation of similar initiatives in Malaysia and elsewhere, as ecosystem approaches to resource management become more important regionally and globally. Collaborative planning processes that involve representative stakeholders in all phases will lead to outcomes that foster the protection of biodiversity and security of livelihoods for many generations to come.

Acknowledgements

The Tun Mustapha Park Project is funded by WWF and the United States Agency for International Development Coral Triangle Support Partnership. Robecca Jumin received a PhD grant from the WWF Russell E. Train Education for Nature Fellowship. Carissa Klein was supported by a postdoctoral research fellowship from the University of Queensland and a Discovery grant from the Australian Research Council (DP 110102153).

Biographical sketches

Robecca Jumin's interest is in conservation planning, and especially in the integration of science and human dimensions in marine conservation and resource management. Augustine Binson is specialized in park management, and ensures that a good governance and management system is in place for Tun Mustapha Park. Jennifer McGowan is focused on developing novel methods for the conservation of mobile marine species, and integrating these methods into spatial decision-support tools. Sikula Magupin is a geographical information system specialist with an interest in coastal management and spatial conservation planning. Maria Beger's research interest is in spatial conservation planning, environmental management and ecology, combining empirical and theoretical approaches. Christopher Brown is interested in the conservation of marine ecosystems and sustainable management of fisheries. Hugh Possingham is Chief Scientist of The Nature Conservancy and a professor at The University of Queensland. Carissa Klein's primary research interest is in supporting marine conservation decisions, especially in tropical ecosystems.