The discussion around the classification of giraffe species and the separation of subspecies is ongoing (Fennessy et al., Reference Fennessy, Bidon, Reuss, Kumar, Elkan and Nilsson2016; Bercovitch et al., Reference Bercovitch, Berry, Dagg, Deacon, Doherty and Lee2017). The South African giraffe has been classified as G. camelopardalis giraffa, G. camelopardalis capensis and G. camelopardalis wardi. Here we refer to the subspecies as G. camelopardalis giraffa, adopting the widely accepted nomenclature and taxonomy that recognizes nine subspecies (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Brenneman, Koepfli, Pollinger, Milá and Georgiadis2007; Dagg, Reference Dagg2014). We examine the status of the South African giraffe in private and public reserves, and National Parks and Provincial Nature Reserves, and the factors that have contributed to an increase in the population of this subspecies.

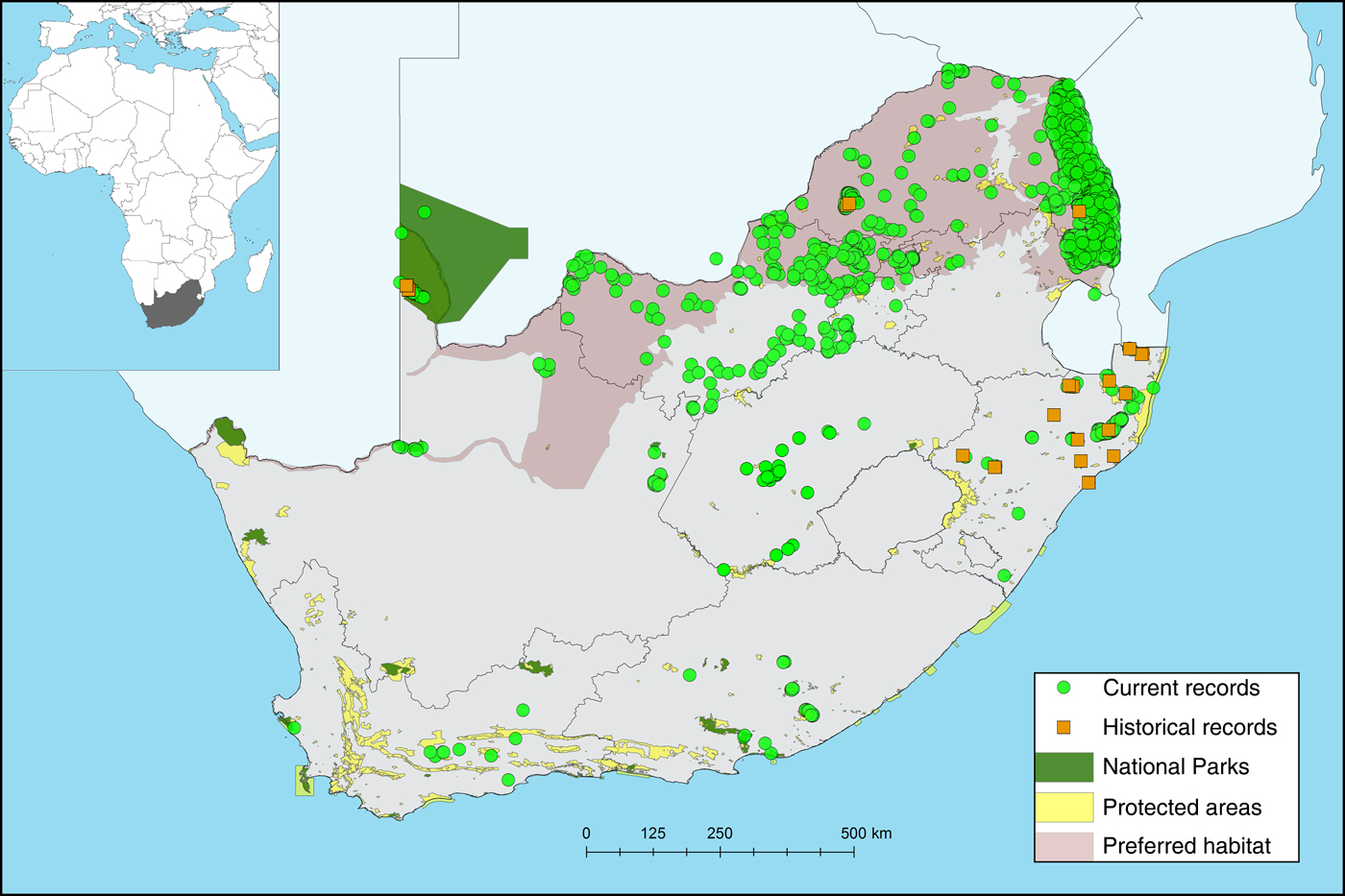

The current range of the South African giraffe is shown in Fig. 1. Within South Africa the subspecies’ preferred natural habitat is predominantly the savannah/woodland areas of Limpopo Province, the lowveld areas of Mpumalanga Province, northern sections of North West Province, and the north-east of Northern Cape Province. The natural distribution of the subspecies also includes sections along both sides of the Mozambique/South Africa border north of Swaziland, the South Africa/Zimbabwe border and the South Africa/Botswana border along the Limpopo River (Deacon & Parker, Reference Deacon, Parker, Child, Roxburgh, Do Linh San, Raimondo and Davies Mostert2016). We consider the giraffes residing in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park to be an extralimital species, given the lack of data on whether there has been interbreeding between the subspecies G. camelopardalis angolensis and G. camelopardalis giraffa (Kruger, Reference Kruger1994; Nico van der Walt, pers. comm.), and therefore this population was omitted from our estimates.

Fig. 1 Current and historical records of the South African giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa. Current numbers include private game farms, private nature reserves, Provincial Nature Reserves and National Parks, totalling 26,919–30,368 individuals.

In 1898 the Sabi Game Reserve, which later developed into Kruger National Park, was estimated to have a population of < 30 giraffes (Koedoe, Reference Koedoe1996). By 1938 the Park's giraffe population had increased to 200 individuals, reaching 3,300 by the late 1960s, and in 1979 the Park's population was estimated to comprise c. 5,000 individuals, with an estimated 8,000 within the whole country by the beginning of the 21st century (Fennessy, Reference Fennessy2009).

A drastic decline in wildlife across South Africa as a result of European colonization and intensive hunting (Selous, Reference Selous1908) prompted the establishment of National Parks and Reserves during 1926–1937 (National Agricultural Marketing Council, 2006; Carruthers, Reference Carruthers2008). As the idea that wildlife should be researched began to take hold in the middle of the 20th century (Kingdon, Reference Kingdon1988), as did the idea that wildlife ranching could provide as productive a livelihood as domestic animal ranching (Dasmann & Mossman, Reference Dasmann and Mossman1960; Carruthers, Reference Carruthers2008; Tutchings & Deacon, Reference Tutchings and Deacon2016). Since the 1960s wildlife numbers on commercial farms have continued to rise, as has their economic value (Smit, Reference Smit and Schutte2006; Carruthers, Reference Carruthers2008). In the early 1980s there were c. 250 privately owned giraffes in South Africa, but following their introduction into numerous private and provincial game reserves (reserves managed by governmental nature conservation authorities; Theron, Reference Theron2005) it is now estimated there are giraffes on most of South Africa's estimated 12,000 game farms and ranches (WRSA, 2014). Populations comprise 1–250 individuals, with a mean of 30 per property stocking giraffes (M. Child, unpubl. data).

To assess the number of G. camelopardalis giraffa occurring in South Africa, we collected data during 2014–2016 by liaising with the managers/owners of the various private reserves, official Provincial Nature Reserves and National Parks. A modified method based on the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria version 3.1 (IUCN, 2001) was used to calculate the Extent of Occurrence (EOO), defined as ‘the area contained within the shortest continuous imaginary boundary which can be drawn to encompass all the known, inferred or projected sites of present occurrence of a taxon, excluding cases of vagrancy’ (IUCN, 1994). Using the range map (Fig. 1) as a baseline, the EOO for each district was considered to be the proportion of land within the district boundaries that encompassed the natural habitat of G. camelopardalis giraffa. We used the counts provided by ranch owners/managers to estimate the number of giraffes on each farm within a district. Ranch and reserve owners who provided census numbers conduct annual game counts via helicopter, fixed-wing aircraft or repeatable drive counts as part of their sustainable game ranching practice, to stock the farm appropriately according to its carrying capacity (Deacon et al., Reference Deacon, Tutchings and Bercovitch2016, unpubl. data). We used the EOO to calculate the approximate number of giraffes on game ranches and farms in each district and within the natural habitat of the subspecies. Based on the EOO we estimated there are 9,642 South African giraffes occurring on privately owned game farms or ranches that are registered with the national wildlife ranching organization (Wildlife Ranching South Africa), and an additional 3,781 in Provincial Nature Reserves.

We made an alternative estimate of the number of privately owned giraffes by multiplying the number of registered farms by the mean number of giraffes per farm, as provided in the farmers’ responses (Table 1). The result (12,059) is higher than that estimated from the EOO. Combining these two alternatrive estimates with the numbers in South Africa's National Parks (Table 2) yields a current population estimate of 21,053–24,502 (based on the EOO) or 23,470–26,919 (based on farmers' responses) G. camelopardalis giraffa in South Africa, with approximately half the estimated population on privately owned land.

Table 1 Numbers of South African giraffes Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa as of 2016 on private farms and/or ranches in South Africa (modified from Deacon & Parker, Reference Deacon, Parker, Child, Roxburgh, Do Linh San, Raimondo and Davies Mostert2016), by province, with number of farms registered with Wildlife Ranching South Africa (WRSA), number of responses (% response rate) and mean number of giraffes per farm provided by owners, estimated total number of giraffes (extrapolated from the number of registered farms), Extent of Occurrence (EOO, see text for details of calculation), total number of giraffes on private farms based on the EOO within each province, and number of giraffes in governmental Provincial Nature Reserves.

Table 2 Numbers of G. camelopardalis giraffa in South African National Parks as of 2013 (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Gaylard, Greaver, Hayes, Cowell and Ellis2013).

Both the genetic purity and the genetic diversity of the South African giraffe are of concern. The unrestricted exchange of giraffes by non-state entities could result in the hybridization of the subspecies where extralimital G. camelopardalis angolensis are, or have been, exposed to populations of the endemic G. camelopardalis giraffa, such as in Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park. Therefore the monitoring of giraffe subpopulations and regulation of associated translocations is imperative to maintain the purity and genetic diversity of the giraffe subspecies.

Globally Giraffa camelopardalis is categorized as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List (Muller et al., Reference Muller, Bercovitch, Brand, Brown, Brown and Bolger2016); however, with no immediate threats severe enough to cause a population decline in the foreseeable future, it has been recommended that the G. camelopardalis giraffa subspecies in South Africa remains categorized as Least Concern (Deacon & Parker, Reference Deacon, Parker, Child, Roxburgh, Do Linh San, Raimondo and Davies Mostert2016; Deacon et al., Reference Deacon, Tutchings and Bercovitch2016, unpubl. data). This recommendation was made in a detailed report by the IUCN Species Survival Commission Giraffe and Okapi Specialist Group (Muller et al., Reference Muller, Bercovitch, Brand, Brown, Brown and Bolger2016). The threats, or lack thereof, were discussed in detail by the Endangered Wildlife Trust and are compiled in their status report (Deacon & Parker, Reference Deacon, Parker, Child, Roxburgh, Do Linh San, Raimondo and Davies Mostert2016). The increase in private ownership of giraffes across South Africa and the economic interest in conserving a thriving, healthy and viable population, and by default a suitable environment for giraffes, have stimulated an increase in giraffe numbers. However, continued monitoring and surveillance of protocols and adherence to best practice are essential to retain a healthy subspecies population, especially as habitat loss and fragmentation, along with landscape changes, continue to reduce the number of suitable environments across the rest of the continent (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Thornton and Kruska2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank South African National Parks, Wildlife Ranching South Africa and all participating ranch owners for providing giraffe population data for this nationwide census, and similarly the Provincial Nature Reserve officials and the various offices of the Departments of Environmental Affairs and Tourism. We thank the National Research Foundation, the Eastern Free State Highlands Nature Club and the Natural Bridge Wildlife Ranch in Texas, USA, for their continued support, and Matthew Child at the Endangered Wildlife Trust for liaison with various stakeholders.

Author contributions

FD collected the study data and liaised with all managers/owners of private ranches and National Parks. FD and AT jointly wrote the article.

Biographical sketches

Francois Deacon is an animal habitat specialist. He quantifies habitat resources in relation to the needs of wildlife species in Africa. Andy Tutchings has been involved with giraffe and elephant conservation in Africa for 15 years and has a passion for conservation education programmes. Both authors are founding members of the IUCN Species Survival Commission's Giraffe and Okapi Specialist Group, currently collaborating on wildlife projects throughout southern Africa.