Introduction

Delirium (Latin: de and lira, “deviate from a line or furrow”) is the most common neuropsychiatric disorder. It is an unspecific, heterogeneous, comorbid brain disorder (Saxena and Lawley, Reference Saxena and Lawley2009). A key feature is the sudden fluctuating disturbance of consciousness or attention and cognition, as well as emotion, psychomotor activity, and perception (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Prevalence rates have often been assessed for elderly hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years. Few studies have focused on “very elderly” or “very old” patients, that is, those aged ≥80 years. The current prevalence rates of delirium in the elderly (patients aged ≥65 years) have been determined through cross-sectional designs of admission and incidence rates during or within the first days of hospitalization. They have usually been estimated from pooled data; thus, they are not generalizable to patients aged ≥80 years. In addition, there have been methodological problems, such as a lack of power, smaller sample sizes with no more than a few hundred patients, and a focus on specific patient populations (Inouye et al., Reference Inouye, Westendorp and Saczynski2014).

A single-day point prevalence-study of 311 adult patients in an acute hospital setting found that in 69 patients aged >80 years, the delirium prevalence rate was 34.8% (Bellelli et al., Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Di Santo2016). A retrospective evaluation of 2 years of data on 1,797 cardiac surgical patients aged >65 and >80 years (Kotfis et al., Reference Kotfis, Szylinska and Listewnik2018) found that 230 were >80 years old and 33.5% developed postoperative delirium. In addition to age, seven independent risk factors for developing post-cardiac surgery delirium were identified: diabetes, elevated creatinine, pneumonia, extracardiac arteriopathy, prolonged hospitalization time, and postoperative atrial fibrillation.

A review of the literature indicated the need for studies on the prevalence of delirium in individuals aged ≥80 years. Many studies have documented the prevalence rates of and risk factors for delirium in patients aged >65 or >75 years. In these age groups, the rates and risk factors have been found to vary by department, such as medical, surgical, and intensive care units (ICUs). Higher overall complication rates, as evidenced by persistent cognitive decline, nursing home admissions, and mortality, have also been reported (Watt et al., Reference Watt, Momoli and Ansari2019).

Life expectancy has increased; thus, the population of very old patients in healthcare facilities has also grown (Arai et al., Reference Arai, Ouchi and Yokode2012). Therefore, an in-depth knowledge of the prevalence rates of and risk factors for delirium is crucial for prevention, advance care planning, and improvements in healthcare professional and caregiver education. This comprehensive study evaluated the prevalence rates of and risk factors for dementia, as well as the medical characteristics of patients aged ≥80 years with delirium.

Methods

Patients and procedures

Patient data from January 1 to December 31, 2014 were prospectively collected from a delirium detection initiative (DelirPath) at the local university hospital, a tertiary care center. A total of 39,442 patients were registered. The exclusion criteria were age <18 years, length of stay <1 day, and missing data. This resulted in 28,860 eligible patients, 3,076 (10.7%) of whom were ≥80 years old (Supplementary Figure 3). To determine the hospital departments, the primary diagnoses were linked to the corresponding departments.

Measurements

The 13-item Delirium Observation Screening scale (DOS) is validated to indicate delirium on the basis of the DSM-IV criteria (Schuurmans et al., Reference Schuurmans, Shortridge-Baggett and Duursma2003; Gavinski et al., Reference Gavinski, Carnahan and Weckmann2016). The items assess the following symptoms: 1, disturbance of consciousness; 2–4, attention; 5 and 6, thought processes; 7 and 8, orientation; 9, memory; 10, 11, and 13, psychomotor behavior; and 12, affect. The symptoms are rated on a scale of 0–1 (nonexistent [0], sometimes to always existent [1], and unable to assess [–]), and the cut-off score for delirium is ≥3 (Scheffer et al., Reference Scheffer, van Munster and Schuurmans2011; Gavinski et al., Reference Gavinski, Carnahan and Weckmann2016). The values were aggregated throughout recordings. This approach was found to be valid. It enabled the correct identification of 91% of delirium diagnoses, as determined by the consultation–liaison psychiatry service.

The Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) comprises eight items based on the DSM-IV criteria. This two-point (absent vs. present) screening instrument was designed for use in ICUs (Bergeron et al., Reference Bergeron, Dubois and Dumont2001).

The electronic Patient Assessment — Acute Care (ePA–AC) is a daily administered nursing instrument. It is used to assess mobility, personal care and dressing, feeding, elimination, cognition and alertness, communication and interaction, sleeping, breathing, pain, pressure ulcers, and wounds (Hunstein, Reference Hunstein2012).

Delirium determination

The DOS and ePA–AC were routinely administered to patients aged ≥80 years upon admission on regular floors. The ICDSC was administered to patients in the ICU three times per day. All instruments (DOS, ICDSC, and ePA–AC) were administered by nurses who had completed courses that included literature research, case reports, and epidemiology.

The determination of delirium was based on the DOS cut-off (≥3), ICDSC cut-off (≥4), DSM-5 criteria (disturbance in consciousness or attention), and the cognition-based construct based on the ePA–AC. This approach correctly identified 91% of the delirium diagnoses, as determined by the local team (n = 9) consultation–liaison psychiatry service (Bode et al., Reference Bode, Isler and Fuchs2019); thus, it was valid. Furthermore, this construct was tested against the validated DOS and ICDSC scales. It achieved almost perfect agreement (Cohen's κ 0.83, p < 0.001).

This study was approved by the local ethics committee (KEK-ZH-Nr. 2012-0263). A waiver of informed consent was obtained from the committee. All reporting followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement (Vandenbroucke et al., Reference Vandenbroucke, von Elm and Altman2014).

Statistical methods

Data analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0, and R version 3.5.0 for Windows. The descriptive characteristics were summarized on the basis of the parametric properties. Percentages are provided for the categorical variables, and means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges are provided for the continuous variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine the normality of the distribution of the data. For the continuous variables, the inter-group differences were assessed with the Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U test depending on their parametric properties, and for the categorical variables, Pearson's chi-squared test was performed.

In the first step, the delirium construct based on the DSM-5 was tested, and its agreement with the validated approach (DOS cut-off ≥ 3 or ICDSC ≥ 4) with Cohen's kappa coefficient was determined as a measure of concordance. Agreement was defined as follows: 0.61–0.80, substantial agreement; >0.80, perfect agreement (Landis and Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977).

In the next step, the data were dichotomized by the presence or absence of delirium. They were then further categorized by managing department (N = 27). Simple logistic regressions were performed to determine the prevalence rates of delirium by medical department and medical characteristics, including the corresponding odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals. Two-tailed tests were used in the inferential statistical analysis, and the significance level (α) was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of patients with delirium

Of the 3,076 patients aged ≥80 years, 1,285 (41.8%) developed delirium (Table 1 & Supplementary Figure 4). Gender was equally distributed across patients with and without delirium, with no significant effect on the development of delirium. The patients with delirium were less likely to have resided at home prior to admission (OR = 0.36). They were more likely to require assisted living services (OR = 2.73), to have been transferred from other hospitals (OR = 2.05), or to be admitted as emergencies (OR = 2.24).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and medical characteristics of patients with and without delirium

a Mean, standard deviation (SD)/median, interquartile range (IQR).

Furthermore, these patients required prolonged hospitalization. The length of stay was twice that of patients without delirium, and they were more likely to require treatment in the ICU. At discharge, the patients with delirium had greater physical and functional impairment, as indicated by the greater need for care at other hospitals (OR = 2.37) and rehabilitation centers (OR = 2.2) rather than the capability to return to their own residences (OR = 0.17). They also had more severe illness and a higher mortality risk during their stay (OR = 24.88).

Prevalence rates of delirium by medical department

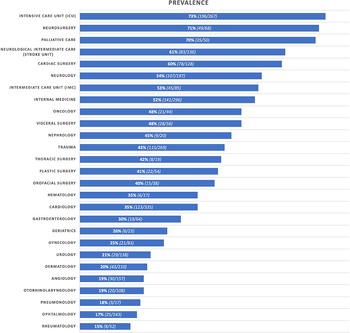

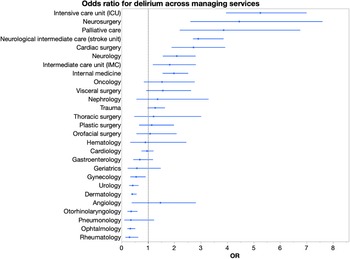

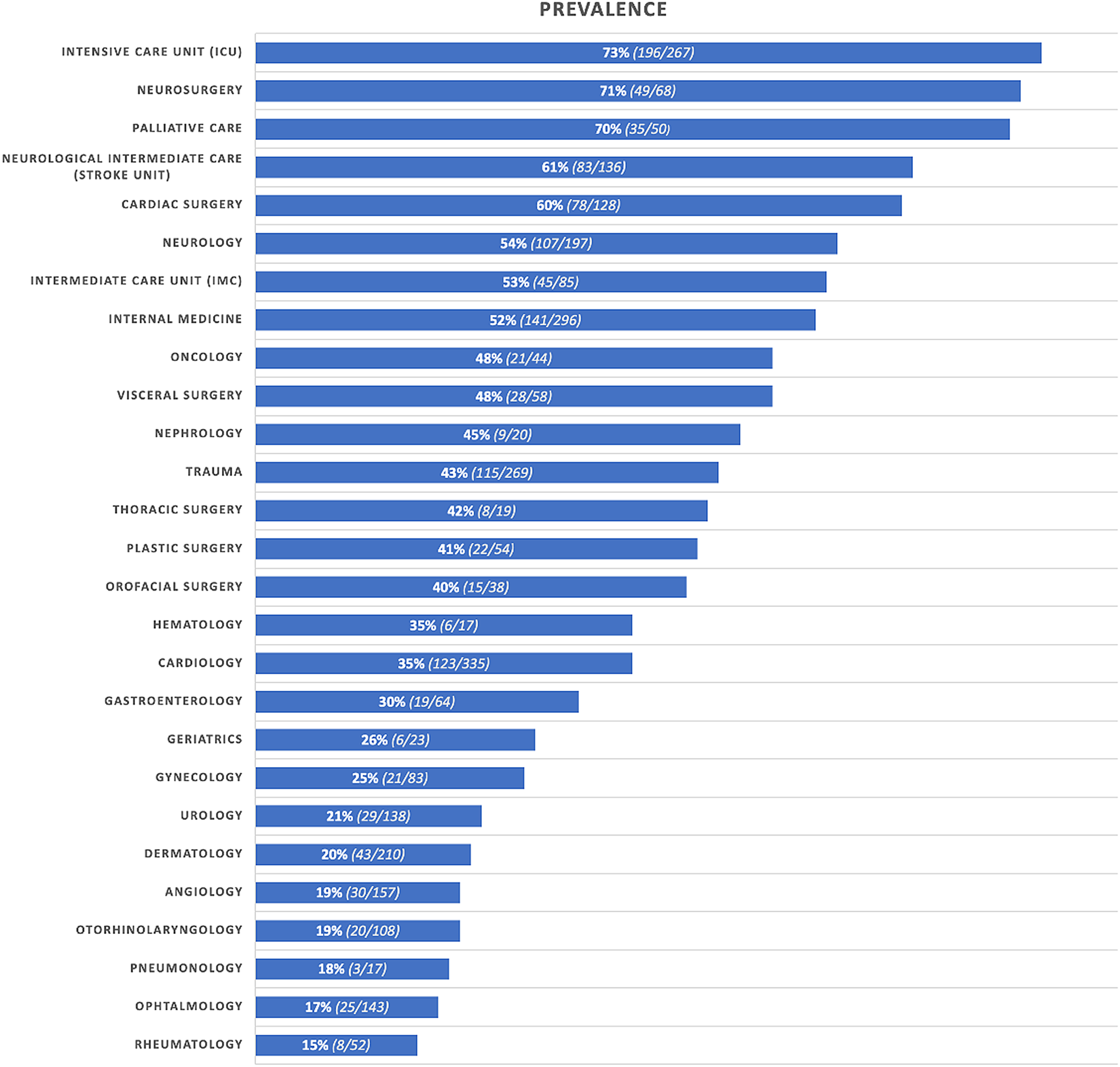

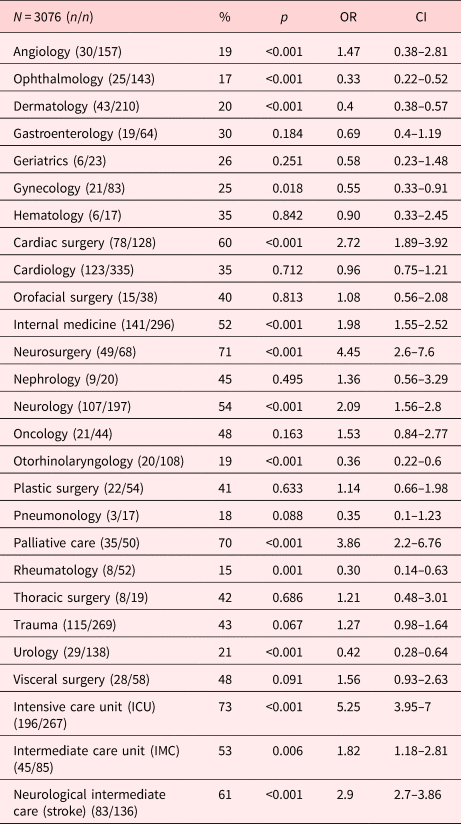

The highest delirium prevalence rates were found in the intensive medical services [ICU, 73%; stroke unit, 61%; and immediate care units (IMCs), 53%; Table 2; Figures 1 and 2]. High prevalence rates were also noted in the specialist departments for patients with brain disease (neurosurgery, 71%; neurology, 54%) and advanced and terminal illness (palliative care, 70%). Conversely, in rheumatology, the prevalence and risk were low (15%, OR = 0.3).

Fig. 1. Prevalence rates of delirium in 27 medical departments.

Fig. 2. Risk of developing delirium: Odds ratios (OR) and confidential intervals (CIs) for 27 medical departments.

Table 2. Prevalence rates and odds ratios for developing delirium

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Main findings

Very old patients, those aged ≥80 years, are an emerging patient population. However, much less data about delirium prevalence rates, risk factors, and further medical characteristics are available for these patients than for the elderly aged ≥65 years. This study of the occurrence of delirium in a population of 3,076 hospitalized patients aged ≥80 years is the largest to date.

The overall prevalence of delirium in patients aged ≥80 years was high: 41.8%. These patients were more likely to be admitted via emergency referrals and from facilities, such as nursing homes and assisted living housing. The length of hospital stay was twice that for other patients. Patients with delirium were less likely to return home (OR = 0.17) and more likely to be admitted to facilities, that is, other hospitals (OR = 2.37), rehabilitation centers (OR = 2.2), or assisted living (OR = 2.96). The mortality risk increased considerably (OR = 24.88).

There were considerable variations in delirium prevalence by medical department. For more than one-third (8 of 27) of the departments, the prevalence rate exceeded 50% (ICU, 73%; neurosurgery, 71%; palliative care, 70%; stroke unit, 61%; cardiac surgery, 60%; neurology, 54%; IMCs, 53%; and internal medicine, 52%). Interestingly, these services were associated with brain, heart, or severe infectious diseases. This confirms the findings of previous studies regarding the increased risk for these patients to develop delirium (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Perkins and Prasad2019; Mossello et al., Reference Mossello, Baroncini and Pecorella2019).

Few studies have discussed the prevalence rates of delirium in patients aged ≥80 years, and comparisons are few (Mazzola et al., Reference Mazzola, Bellelli and Broggini2015; Eide et al., Reference Eide, Ranhoff and Fridlund2016; Kotfis et al., Reference Kotfis, Szylinska and Listewnik2018). Thus, studies describing the prevalence rates in patients aged ≥65 years were considered. Men have been found to be at a higher risk for developing delirium (1) and other diseases (Angele et al., Reference Angele, Pratschke and Hubbard2014; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Tanislav and Kostev2019). This also applies to patients aged ≥65 years. In those aged ≥80 years, being male was not a risk factor. The reasons might be life expectancy and sociodemographic distribution.

The role of the residence prior to admission has not yet been studied in detail; however, patients admitted from assisted living facilities have been found to have worse outcomes (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Mendelson and Bingham2008; de Saint-Hubert et al., Reference de Saint-Hubert, Schoevaerdts and Poulain2009). Assisted living residency housing prior to admission has been found to be a predisposing factor in delirium (OR = 2.72), and independent living has been associated with a low risk (OR = 0.36). Similarly, in the present study, very old patients with delirium were almost twice as likely to be admitted from nursing homes (OR = 2.2) than from their own residences. Assisted living has been found to be associated with higher morbidity (Kosar et al., Reference Kosar, Thomas and Inouye2017; Vossius et al., Reference Vossius, Selbæk and Šaltytė Benth2018), and multimorbidity (Inouye, Reference Inouye2018). This suggests that assisted living might be a predisposing factor for delirium. This finding could enhance awareness of delirium in very old individuals, especially in emergent situations in which it is under-detected (Elie et al., Reference Elie, Rousseau and Cole2000).

Emergency admission was a substantial risk factor for developing delirium (OR = 2.24). Patients in the emergency room often suffer from multimorbidity involving acute decompensated diseases (McPhail, Reference McPhail2016); thus, the occurrence of delirium might be indicative or predictive of disease severity and trajectory. This was supported by the prolonged hospitalization. The average hospital stay of patients with delirium was twice as long as that of other patients (12.3 vs. 7.8 days). Their mortality risk was substantially higher (OR = 24.88). It was also considerably higher than that found in prior studies (Mazzola et al., Reference Mazzola, Bellelli and Broggini2015). Regarding the increased mortality risk resulting from delirium, it was not methodologically possible to distinguish the incidence of suicide. This is relevant because the prevalence of suicide as a consequence of neuropsychiatric disease has been underestimated (Arciniegas and Anderson, Reference Arciniegas and Anderson2002; Coughlin and Sher, Reference Coughlin and Sher2013; Costanza et al., Reference Costanza, Baertschi and Weber2015, Reference Costanza, Amerio and Aguglia2020a, Reference Costanza, Amerio and Radomska2020b; Eliasen et al., Reference Eliasen, Dalhoff and Horwitz2018).

A highly relevant clinical finding was the prevalence of delirium in the very old, that is, patients aged ≥80 years. The prevalence in the general population was found to reach 20% (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Weiner and Arora2016); however, it was twice as high (41.8%) in the very old. Thus, two out of five patients aged >80 years developed delirium during hospitalization. The prevalence rates of delirium in patients aged ≥80 years by medical department were found to be highest in the ICUs and IMCs. Previous studies on ICUs have found wide variations (7–89%) in the prevalence rates of dementia. For patients aged ≥80 years, the rates increased to 53–73%.

Limitations

The large sample size, which included consecutive admissions over 1 year, is a strength of this study. There are a few limitations. The etiologies of delirium (e.g., previous dementia, sepsis, or brain tumor) were not included in this analysis. The patient sample was from a tertiary care center; thus, replication is needed to facilitate generalizability to other healthcare settings.

Implications

Unlike previous studies on elderly individuals, this study has comprehensively described the prevalence rates of delirium in a large sample. Thus, the findings are based on the data for patients aged 80–102 years in 27 medical departments. With an aging society (7), studies need to focus on the growing number of older patients among hospitalized populations. The findings of the present study indicate that delirium was frequently diagnosed in those aged ≥80 years. Specifically, patients admitted as emergencies or from assisted living housing were hospitalized longer. In addition, they were more likely to die before discharge or to require assisted living housing upon discharge. These findings could inform advanced care planning. They also confirm those of previous studies regarding the need to screen patients aged ≥80 years, and even those who are younger, for delirium.

Conclusion

Delirium occurs frequently in individuals aged >80 years. It is likely underdiagnosed; however, it is an indicator for the subsequent loss of independence and, ultimately, mortality. This study is the largest to assess the prevalence and medical trajectories of very old patients with delirium. This study extends the limited knowledge about delirium, a life-threating condition, in an increasingly aging society. These results also suggest that the accurate detection of delirium in patients aged >80 years could be achieved with the nursing instruments used in daily practice. Studies on delirium outcomes are required to determine the potential of the approach adopted in this study for maintaining the independence of and lowering the morbidity and mortality rates in this growing population.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951521001814.

Acknowledgment

We thank the clinical staff who made this study possible.

Funding

This work was supported by the clinician scientist program of the medical faculty of the local university (Program Number: 45800).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.