Introduction

Family is usually involved in medical decisions and provides assistance in the patients’ daily routine main activities in a palliative care context (Leow et al., Reference Leow, Chan and Chan2014). Thus, palliative care is based on an interaction and communication flow in a caregiving triad: the patient, the healthcare professionals, and the family. The general aim is to improve the quality of life both of the patients facing a potentially deadly disease but also their families via the prevention and relief of suffering (Hauser and Kramer, Reference Hauser and Kramer2004; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Davies and Higginson2010; Nambisan, Reference Nambisan2010).

In addition to physical suffering, psychological and spiritual distress are a major problem for palliative care patients and their families. It contributes to a decreased quality of life and increases patients’ and families’ suffering. Such distress is a huge challenge for healthcare professionals who care for these patients (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013; Rego et al., Reference Rego, Pereira and Rego2018; World Health Organization, 2018). Psychological suffering for palliative care patients is also often framed in terms of loss of dignity (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005). Dignity Therapy (DT) was developed by Chochinov et al. (Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005) as a brief and individualized psychotherapy based on the dignity model. Its primary purpose is to help patients with advanced disease to free themselves from the usual psychological and emotional anxiety by providing them with an opportunity for creativity or legacy. The aim is to reduce their suffering and increase their dignity. It also aims to help these patients to find a new meaning of life (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005; Fitchett et al., Reference Fitchett, Emanuel and Handzo2015).

DT first gives the patient a questionnaire that aims to be the guide of the forthcoming conversation with the therapist helping him/her to reflect upon the life moments that are more important and that they may want to convey to their loved ones: parts of their lives they feel that are or were more meaningful, stories that most would like to be remembered, or even some advice to their families or friends (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005). This conversation is recorded, transcribed, and edited in a document as a final legacy. It is then delivered to the patient who, if and when he/she wishes, may share with the people he/she most cherishes. Alternatively, the document is delivered to patients’ family members or other loved people but is always according to his/her specific will (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Opio2011; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Opio2015; Martinez, Reference Martínez, Arantzamendi and Belar2016).

Evidence shows that DT is effective in the reduction of several pathological issues related to the patient's end-of-life psychosocial experience: depression, anxiety, demoralization, dignity, wish of death, and suffering (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011; Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2014, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2017). However, its impact on the palliative patients’ family members is less explored. As mentioned before, the welfare of family members of someone who faces a terminal diagnosis is closely linked to the patient's welfare (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; EAPC, 2013). Thus, worries about the dignity and the path of end-of-life healthcare are provided to palliative patients with implications for both of them and their families (in the palliative phase and in the bereavement phase) (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007).

In this last phase — bereavement — families are challenged to adjust their daily lives without the physical, social, and psychological presence of their loved one. In addition to the end of the family as they knew it, each family member (with the death of the palliative patient), loses his individual relationship with him (Corless, Reference Corless, Ferrel and Coyle2001). DT has shown signs of being able to help in this difficult phase and is, therefore, of great importance for family members. In addition, the legacy document is usually delivered to the family members who, therefore (directly or indirectly), may experience the effects of DT (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007). This systematic review emerges from that context with the aim of exploring and synthesizing existing evidence about the impact that DT may have on the palliative patients’ family members.

Methods

A comprehensive systematic review using the PRISMA guidelines was conducted (Liberati et al., Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff2009; Shamseer et al., Reference Shamseer, Moher and Clarke2015).

Search strategy

In June 2020, a systematic review of the literature related to the terms “Dignity Therapy” and “Palliative Care” was undertaken in the following databases: TRIP database, Web of Knowledge, Scopus, Cochrane library, and PUBMED; no articles were excluded based on their publication date.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: articles published in Portuguese or English focusing on adult family members (≥18 years old) of palliative care patients to whom DT (intervention) had been applied in comparison (whenever possible) to a group with the same characteristics but who had achieved standard palliative healthcare/without intervention. The measured outcome was the effect of DT on the family members’ psychosocial and spiritual levels. Quantitative and qualitative studies were included. Studies performed on <18-year-old patients and/or family members were excluded as were ones that did not include the palliative patients’ participating family members. Opinion articles, clinical cases, review articles, guidelines, news, and editorials were also excluded.

Data collection and analysis process

Study quality and eligibility were performed individually by two researchers. Data extraction was done manually without any extraction software. The results were subjected to critical review by two researchers and a coordinator. Any differing opinions regarding the articles’ relevance were solved by reaching a consensus among the authors. The evaluation of the quality and evidence level (EL) of the included articles was discussed and decided by consensus among the authors. The EL and the strength of recommendation (RF) were assigned by the authors considering the criteria of the scale Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) of the American Family Physician (Ebell et al., Reference Ebell, Siwek and Weiss2004).

Results

Identification of studies

We found 294 articles using the search terms “Dignity Therapy” and “Palliative Care” in databases: 40 in the TRIP database, 117 in the Web of Knowledge, 50 in the Scopus, 25 in the Cochrane library, and 62 in PUBMED. Of these, 126 were duplicates and were excluded. Another 137 were excluded due to title and abstract readings leaving a total of 31 articles to be evaluated on a full reading basis. Out of this reading, 23 articles were excluded for not respecting the previously defined inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flow diagram of study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram showing the literature method search. n, the number of articles.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias was determined to evaluate the quality of the selected studies. The EL was assigned by the authors according to the SORT scale criteria (Ebell et al., Reference Ebell, Siwek and Weiss2004). The article-by-article evaluation is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Evaluation of the risk of bias

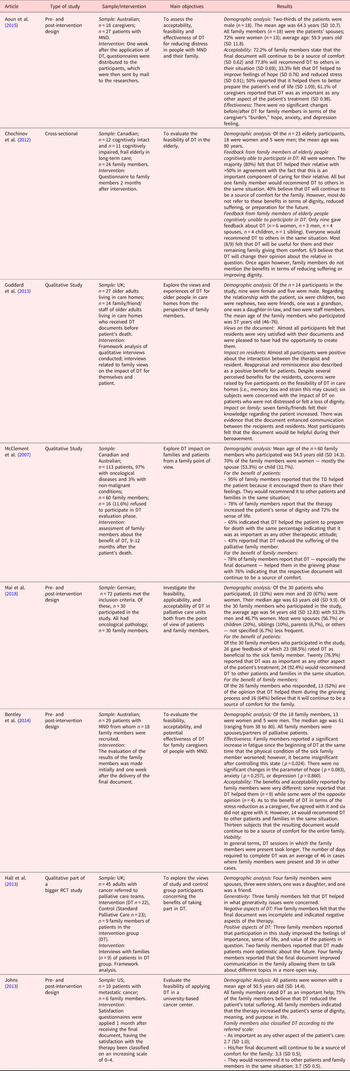

The characteristics of the studies evaluated in this review are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Systematic review results

Context of the studies and characteristics of the samples

The studies selected samples of populations from Australia (n = 3; 37.5%), Canada (n = 2; 25%), the United Kingdom (n = 3; 37.5%), and Germany (n = 1; 12.5%). In addition, n = 2 (25%) were carried out in elderly care homes (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013), n = 1 (12.5%) in palliative healthcare units (PHU) (Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018), n = 1 (12.5%) with patients under palliative healthcare teams (not having been specified in which context that healthcare was carried out) (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013), and n = 1 (12.5%) in terminal patients in the community (Johns, Reference Johns2013); the place of the study was not clearly specified in three studies (37.5%) (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). The patients involved in the studies mostly had oncological pathologies (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Johns, Reference Johns2013; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018) or motor neuron disease (MND) (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). In two of the studies, the patients were frail elderly people in care homes (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013).

The number of family members in the samples varied between 6 and 60: n = 6 (Johns, Reference Johns2013); n = 9 (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013); n = 14 (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013); n = 18 (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014); n = 18 (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015); n = 24 (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012); n = 30 (Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018); and n = 60 (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007) (Table 2). In the studies in which this information was available, they were mostly female constituting from 64.3% up to 72% of the sample (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015), except for one in which they were mostly men (53%) (Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). This information is not present in n = 3 (37.5%) of the studies (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Johns, Reference Johns2013). Most studies (62.5%) showed that the family members were mostly composed of the patients’ spouses (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018), except for one of the studies in which most family members were patient's children (12.5%) (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013). This information was not available in n = 2 (25%) of the articles (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Johns, Reference Johns2013). Three of the studies (37.5%) included not only family members but also friends (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013), care home staff designated by patients to be the recipients of the “generativity” document (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013), or even “others” — not specified (Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018) (Table 2). Finally, the median age was 57 with a minimum age of 54 years old and maximum age of 61 years old in relation to the analyzed family members’ age. This information was not provided in three articles (37.5%) (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Johns, Reference Johns2013).

Data collection method

All studies analyzed the effect of DT from the family members’ viewpoint. This includes their perception about the therapy effects on themselves and on the rest of the family as well as the perception of its effects on the ill family members. The family members’ feedback was obtained in all articles through a satisfaction questionnaire only varying the time in which it was applied: one week (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015), 1 month (Johns, Reference Johns2013), or 2 months after the administration of DT to the patient (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012) or 9–12 months after his/her death (Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). In three of the articles, there was no reference to the moment in which the questionnaire was applied (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). In most studies, the questionnaire was sent by e-mail or by mail (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). In one study, it was carried out in the form of an interview (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013). In the remaining ones, there was no reference to the way it was applied (McClement et al., Reference Martínez, Arantzamendi and Belar2007; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Johns, Reference Johns2013; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). In addition to the satisfaction questionnaire, interviews with the family members were also conducted in two of the studies (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018): This was by phone call in one of them (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013); no details were given in the other case.

Main outcomes: Acceptability and effectiveness

In the selected studies, the effects of DT on palliative patients’ family members psychosocial and spiritual levels were analyzed in terms of acceptability and effectiveness. Acceptability is based on family members’ perception about the usefulness of the intervention in several areas: the impact of care on the stress level, the impact on hope, preparation of the patient for end of life, and the impact on bereavement. Effectiveness was evaluated using validated scales in terms of the caregiver's burden feeling (through the application of the “Zarit Burden Interview – ZBI-12”) as well as in terms of anxiety and depression [quantified by the scale of Anxiety and Depression (HADS)]. One of these articles assessed the effectiveness independent of these two aspects and further analyzed the parameter “hope” that was determined via the Herth Hope Index scale.

Acceptability

Acceptability was analyzed in all of the studies. The final document was considered a source of comfort by the palliative patients’ family members, and most of them would recommend DT to other people in the same situation as theirs (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Johns, Reference Johns2013; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). Furthermore, the family members believe that DT helped them to better prepare for the end of life of the palliative patient (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). Some even mentioned that the intervention helped them to overcome the bereavement in a better way (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). In addition, the family members considered DT to be as important as any other aspect of the patient's treatment (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Johns, Reference Johns2013; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). The influence of DT in the stress level of care was studied in two articles (25%) (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015): The results were more heterogeneous and contribute to this reduction (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). This was not seen in the other study (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014). Finally, in the only article that evaluated the impact of DT on hope in terms of acceptability, 33.3% of the families felt that DT helped to improve their hope (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015).

Effectiveness

Effectiveness of DT was analyzed in only two of the included articles: Bentley et al. (Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014) and Aoun et al. (Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). In terms of effectiveness, there were no significant changes pre-/post-DT for the family members in terms of the caregiver's burden feeling (ZBI-12), anxiety, and depression (HADS) (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). One of those articles, apart from these two aspects, further analyzed the hope parameter via the Herth Hope Index scale. There were no significant differences (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014).

Limitations

Some aspects of disagreement were sometimes mentioned despite the fact that most family members were favorable to DT. In this context, some family members viewed the reading of the final document as potentially being hurtful or causing more suffering in the family in the bereavement process itself. They further suggested that it may sometimes portray the patient in an incomplete or imprecise way thus creating a distorted image of him/her. Finally, they considered the possibility of DT being physically/emotionally demanding for the patients not only due to the disease progression but also due to the implicit end-of-life message of this therapy (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013).

Discussion

DT is a psychotherapeutic approach based on a validated model of dignity in palliative patients (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005). Unlike most of the other palliative healthcare interventions that are more focused on symptoms, the effects of DT lie in its potential to improve the life meaning of the patients to whom it is applied (Chochinov, Reference Chochinov2007). In the field of DT, several studies have evaluated the psychosocial, spiritual, and physical effects of this intervention in palliative patients, but there are still only a few that have evaluated these outcomes on palliative patients’ family members. While DT's main focus is on the patient, family members are also a very important part and a potential target for this therapy (Hauser and Kramer, Reference Hauser and Kramer2004). Family caregivers often experience feelings of anxiety, exhaustion, and discouragement; they can potentially benefit from interventions that can mitigate these feelings such as DT (Adelman et al., Reference Adelman, Albert and Rabkin2004). Surprisingly, research on the effects of DT on family members is still rare. In addition, the literature has only a systematic review about these effects on family members based on different criteria (Scarton et al., Reference Scarton, Oh and Sylvera2018). Thus, further studies are needed to deeply explore the benefits of this therapy not only for the patients but also for their families.

In the studies that assessed the DT effects on palliative patients, it is clear from the literature that DT has a positive impact in terms of acceptability especially in patients’ dignity (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011; Houmann et al., Reference Houmann, Chochinov and Kristjanson2014; Rudilla et al., Reference Rudilla, Galiana and Oliver2015; Donato et al., Reference Donato, Matuoka and Yamashita2016; Julião et al., Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2017; Scarton et al., Reference Scarton, Oh and Sylvera2018), opinions about the benefits of the therapy (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Opio2011; Fitchett et al., Reference Fitchett, Emanuel and Handzo2015; Martínez et al., Reference Martínez, Arantzamendi and Belar2016), decreased suffering (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Opio2011, Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Martínez et al., Reference Martínez, Arantzamendi and Belar2016; Julião et al., Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2017), will to live (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Houmann et al., Reference Houmann, Chochinov and Kristjanson2014; Fitchett et al., Reference Fitchett, Emanuel and Handzo2015; Donato et al., Reference Donato, Matuoka and Yamashita2016; Martínez et al., Reference Martínez, Arantzamendi and Belar2016; Julião et al., Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2017; Scarton et al., Reference Scarton, Oh and Sylvera2018), and life purpose (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005; Houmann et al., Reference Houmann, Chochinov and Kristjanson2014; Fitchett et al., Reference Fitchett, Emanuel and Handzo2015; Donato et al., Reference Donato, Matuoka and Yamashita2016; Scarton et al., Reference Scarton, Oh and Sylvera2018). The acceptability parameter was evaluated here, and the results of this review were similar to palliative patients’ family members, suggesting that DT can have the same positive effects.

On the other hand, the effectiveness results with regard to palliative patients were less consistent in terms of depression and anxiety scores. The results were favorable in some studies (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2014); others were not statistically significant (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Donato et al., Reference Donato, Matuoka and Yamashita2016; Martínez et al., Reference Martínez, Arantzamendi and Belar2016). The same phenomenon occurred in this review for palliative patients’ family members. There were no significant changes pre-/post-DT in terms of effectiveness for family members (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). In articles whose results in terms of effectiveness for patients were favorable, the study sample experienced high levels of depression and anxiety at baseline. The authors suggested that low base rates of distress and anxiety were a possible explanation for the inability to demonstrate DT's influence on this outcome in other studies (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2014). In fact, the studies in this review that analyze this outcome for palliative patients’ family members found that there were no significant changes but do suggest that DT can decrease anxiety and depression in family caregivers who are experiencing moderate to high levels of distress (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015). Similarly, a letter to the editor presented the effects of DT on 25 palliative patients’ family members using the mental health inventory (MHI) in which the family members indicated moderate to high psychological well-being before the intervention: The results showed no significant differences before and after the intervention — likely because of the high baseline MHI scores (Julião, Reference Julião2017). Thus, further studies are needed to better explore this point — preferably with participants with high baseline levels of anxiety and depression.

The gender of the caregiver seems to influence the experience of caring for the palliative patient (Washington et al., Reference Washington, Pike and Demiris2015). In this review, most family members were female and the patient's spouse makes it difficult to extrapolate the results to the remaining family members. Examples include friends or other acquaintances (like care home staff) that are sometimes designated by the patients to be the receivers of the final document (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018) and that are often also involved in the care of these patients. In general, to fully evaluate the effect of DT in demographic terms, it would be necessary in all analyzed articles to characterize both the patient getting the therapy and his/her family members in a better way. It would also be helpful for future researchers to understand the wide range of recipients to whom DT documents are provided. This could ascertain its effectiveness according to the presented characteristics but also understand in which family members/friends/other acquaintances and with what characteristics the therapy may be more effective. The studies that analyze these parameters do not do it in a critical way — they present the results only quantitatively (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018).

Most patients in these studies had cancer (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Johns, Reference Johns2013; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018), which is similar to the WHO report. Oncological pathologies are one of the main pathologies suffered by patients in need of palliative care (World Health Organization, 2018). It would be interesting to study the impact of DT on family members of patients with other types of pathologies besides cancer and MND, i.e., chronic cardiovascular and respiratory disease.

When DT is provided in the last few weeks or months of life, patients and their families may experience it quite differently than when it is provided in the last few years of life. Two of the studies were about frail elderly people in care homes who may not be typically seen as terminal patients; their main objective was to assess the feasibility (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013), acceptability, and potential effectiveness (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013) of DT in older people in care homes. The findings of these two studies suggest that DT may be useful for enhancing the end-of-life experience for residents and their families. They introduce evidence that DT has a role to play among this population suggesting the need for further study in this area. Thus, existential issues facing the elderly likely approximate those facing people who are approaching end of life because of illness (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012).

The time in which the final evaluation was applied, in the studies in which it was known, also varied between one week after the performance of DT and 12 months after the death of the patient in question. This later case involved family members already in the bereavement phase. Bereavement is a complex and multidimensional process that involves the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domain (Sanders, Reference Sanders1999; Chochinov, 2005). The experience of losing someone close often comes up as a profound change in an individual's life path involving a lengthy process of restructuring the meaning of the loss in which the individual has to relearn how to live in a new world without the person lost (Puigarnau, Reference Puigarnau2010). The moment of application of the evaluation about the effects of the DT can thus depend on the moment it was applied and, consequently, on the stage the family is going through. This leads to different evaluations by the family members who are inherently at different stages in the course of the disease or the bereavement for the palliative patient in question (Kübler-Ross, Reference Kübler-Ross1969).

It is also necessary to consider how the respective evaluation of the therapy was carried out. Besides indicating a lack of standardization, this may also have influenced the family members’ responses. For instance, family members who answered questions in person or on the phone with a member of the research team — especially in cases where they were the ones who applied the therapy — may have inhibited them from highlighting any potential negative aspects of the therapy thus constituting a limitation of the studies in question. This approach to evaluation can be seen in a positive way because this contact with the therapist/research team may give way to the creation of a therapeutic alliance and to a future feeling of ease for the family to address sensitive issues that they may need to face. Furthermore, the benefits of this therapy are complemented by a personalized description based on the participants’ free comments introducing subjectivity (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). This heterogeneity and subjectivity can be beneficial from the viewpoint of reading each individual study. It can allow the benefits of the therapy to be addressed in a more broad, unique, and comprehensive way. However, the measures used in these studies may vary depending on the country, culture, socio-economic status, age, gender, marital, and familial status, i.e., single, have children or close family members, or if they have gone through a similar disease/situation of a family member (death in palliative care). The specific outcomes that could be affected include acceptability, the notion of benefit from the therapy, a feeling of reduced stress, improved parameters of hope, and better preparation for the end of life. This impact is due to the subjective conceptual character and difficulty in generalizing these feelings.

A key limitation of most studies in this review was the low number of participants (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Cann and Cullihall2012; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Speck and Martin2013; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013; Johns, Reference Johns2013; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, O'Connor and Breen2014; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2015; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Goebel and Jentschke2018). This makes it difficult to extrapolate the conclusions to the general population. This comparison was not made except for one of the articles in which there was a control group submitted to standard palliative care compared with another one that received standard care in addition to DT (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Speck2013). To determine the effectiveness of this therapy for family members and patients, future prospective studies with suitable controls should be performed as in Julião et al. Here, DT improved depression and anxiety in the treated patients (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2014, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2017).

All of these findings raise important questions: Namely, whether the same would be true in patients with different characteristics from the patients analyzed in the studies in this review, whether the measures used are the most appropriate to assess the effects of this type of intervention, and whether the results would be similar in studies with a larger number of participants because most of these studies had small sample sizes.

Conclusion

The main objective of this systematic review was to explore the psychosocial and spiritual outcomes of DT on palliative patients’ family members. The importance of family members in palliative care is recognized worldwide and is an integral part of the WHO definition of palliative care (World Health Organization, 2018). In this context, it is necessary to perform more studies involving the family members of palliative patients as participants with the aim of covering the entire care unit for patients at the end of their lives (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Davies and Higginson2010; Nambisan, Reference Nambisan2010). Without the perspectives of family caregivers, it is difficult to fully understand the needs for palliative care and develop effective interventions in this regard (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Deas and Howting2016).

The evidence suggests that family members generally believe that DT will better prepare patients for end of life and overcome the bereavement phase. In addition, the legacy document was considered to be a source of comfort, and most family members would recommend DT to others in their situation considering DT as important as any other aspect of the patient's treatment.

The results of this systematic review are encouraging but still reveal many aspects that need to be investigated further so that DT can be used in the most appropriate and beneficial way possible. Further studies are also needed to evaluate the effects of DT on family members. They should preferably be methodologically more uniform: not only in relation to the patient samples but also to the measures used to quantify the benefit of this therapy, forms of evaluation, as well as ways and times in which the therapy is applied. Thus, the conclusions can be more objectively useful and generalizable. It would also be interesting to perform studies with a larger number of participants and, whenever possible, with a control group. The results of such studies could have a significant impact on the way patients and family members deal with end of life and bereavement issues. This could improve the overall well-being of these patients and their families.

Authors' contribution

All authors contributed substantially to either or both of the study conception and/or to the data acquisition, analysis, or interpretation. All authors contributed substantially to the drafting or revising of the manuscript. All authors have given final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This review received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.