Introduction

Even after one year into the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the situation poses an enormous challenge to healthcare systems and societies around the world. In the beginning, medical care activities focused on the provision of intensive care beds for patients developing severe respiratory decompensation related to COVID-19 (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum2020). Furthermore, the reduction of physical contacts in the society and recently vaccinating the population are currently the most important measurements to get the pandemic under control. Even though the development in Germany was less severe in comparison to other European countries, more than 80,000 people died of or with COVID-19 in Germany by May 2021 (RKI, 2021). Additionally, poorer care of non-COVID-19 patients has been described (“Corona Collateral Damage Syndrome”) (Ramshorn-Zimmer et al., Reference Ramshorn-Zimmer, Fakler and Schröder2020).

Palliative and end-of-life care aim to alleviate suffering and improve the quality of life of patients with life-limiting illnesses at the end of life and is now an integral part of many healthcare systems (Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, 2020). Early in the pandemic, the German Society for Palliative Medicine (DGP) published recommendations for the care of patients with COVID-19 (Nehls et al., Reference Nehls, Delis and Haberland2020) and for the support of burdened, seriously ill, dying, and grieving people from a palliative care perspective (Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020). In addition, the DGP contributed to further recommendations on preclinical decision-making (Deutsche Interprofessionelle Vereinigung – Behandlung im Voraus Planen (DiV-BVP) et al., 2020) and prioritization of patients when resources are scarce [Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin (DIVI) et al., 2020].

There have also been a number of international publications on palliative and end-of-life care in pandemic times. Reports from patients, general practitioners, and nursing homes but also from palliative care providers showed that both the identification of individual preferences and the quality of care for seriously ill and dying patients varied greatly (Fallon et al., Reference Fallon, Dukelow and Kennelly2020; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Ekström and Currow2020; Radbruch et al., Reference Radbruch, Knaul and de Lima2020; Trabucchi and De Leo, Reference Trabucchi and De Leo2020). For example, the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), as well as strict isolation policies and visiting restrictions, led to great distress among those affected and those caring for them (Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020; Mottiar et al., Reference Mottiar, Hendin and Fischer2020). However, creative and innovative initiatives emerged with the aim of maintaining palliative and end-of-life care for patients and relatives and making it possible under limited contact conditions, e.g., “Palliative Care Pandemic Pack” for non-specialists (Ferguson and Barham, Reference Ferguson and Barham2020). Early in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, Etkind and Arya emphasized the pivotal role of palliative care in the pandemic including symptom management, training non-specialists, and participating in triage discussion (Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020; Etkind et al., Reference Etkind, Bone and Lovell2020).

Overall, it has become evident that the healthcare system in Germany was not sufficiently prepared for the challenges of palliative and end-of-life care in times of a pandemic.

To increase the pandemic preparedness of the German health care system, the Network University Medicine, funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research, was created, comprising 13 large-scale projects covering surveillance, testing, evidence synthesis, etc. One of the projects focuses on Palliative Care in Pandemic Times (PallPan) to develop a National Strategy for the Care of Seriously Ill Patients and their Relatives with recommendations based on studies examining the current situation of dying patients in the pandemic and existing evidence. This scoping review is, besides a number of other studies, the basis for PallPan developing and consenting recommendations for palliative care in pandemics. It is intended to elaborate an overview and summarize the literature about what is already known.

As the pandemic situation is developing quickly and new evidence is emerging almost daily, the aim of this review was to identify and synthesize relevant aspects and non-therapeutic recommendations of palliative and end-of-life care of seriously ill and dying people, infected and uninfected, and their relatives after one year into the pandemic to outline what actions, practices, and procedures were taken to deal with the pandemic and its consequences.

Methods

Design

We conducted a scoping review following the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guideline (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Godfrey, McInerney and Aromataris2015). The decision for a further review was based on the wealth of new publications following the experiences after one year into the pandemic to incorporate the latest literature for the development of the previously mentioned National Strategy for the Care of Seriously Ill Patients and their Relatives. A scoping review was preferred to a systematic review to map the current literature on palliative care and pandemics rather than to appraise the evidence on a specific research question (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Peters and Stern2018).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The literature to be examined refers to recommendations for action, practices, and procedures on palliative and end-of-life care undertaken by providers and on system level in the context of pandemics. Both published and unpublished primary studies and reviews of quantitative and qualitative research results, editorials, letters, reports, statements, and guidelines were included. The review contains every type of recommendation for the care of adult critically ill patients with advanced end-of-life conditions and dying patients with or without infection and for the care of family members and bereaved relatives in pandemics. Studies on communication strategies for end-of-life care of critically ill patients were included, as well as publications on the use of telemedicine and its benefits in the context of palliative care in times of pandemic. Furthermore, studies on the psychological (and physical) burden of palliative care and primary care professionals (mental health of professionals) were taken into account.

All references dealing with pediatric palliative care, screening, and testing to contain or prevent outbreaks (e.g., in nursing homes) were excluded as they were not part of the planned recommendations. In addition, descriptive studies on infected (COVID-19-) patients and publications that did not include or were not applicable to the context of palliative care were excluded.

Population

Publications focusing on adults aged 18 years and older dying (infected and not-infected) because of a severe, incurable disease, and their caring or bereaved relatives were included. In addition, all professional groups and institutions are involved in their care, both inpatient and home care, as well as specialist and non-specialist providers.

Literature search

We searched the database MEDLINE (PubMed) on 30th September 2020 and updated the search on 11th February 2021. Relevant articles that were known to the authors were included. All references were transferred to Endnote.

Search strategy

We developed the following search strategy using a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms related to palliative care in times of pandemic, which led to the combination of the following terms: Palliative*care* OR palliative*medicine* OR residential*facilities* OR terminal*care* AND COVID-19* OR corona* OR pandemic* OR pandemic*preparedness*. Search terms had to be included in the title/abstract. Only German and English literature was taken into account, with no restriction regarding the year of publication. Finally, a manual supplementary search was conducted on websites of international and national specialist palliative care associations, in newsletters and search engines (Google, Google Scholar).

Data extraction/synthesis of results

Titles and abstracts of the identified publications were screened by three researchers (EL, DG, SG) relying on the established inclusion–exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were discussed between the three researchers and, if necessary, solved with the senior author (CB). Afterward, all full texts were imported into the qualitative data analysis software MaxQDA and were appraised against the inclusion criteria by the three researchers and coded using a predetermined coding guide. The coding guide relies on key topics identified by clinical experts during a digital workshop. Since the results of the synthesis of the literature should primarily be used for the preparation of the recommendations of the PallPan project, we have decided to stick to the topics identified as most relevant for the planned recommendations by expert consensus. The eight key topics are (1) patient autonomy and decision-making, (2) communication with patients/families and strategies for the healthcare system itself, (3) symptom relief for patients infected with COVID-19, (4) enabling contact with relatives, (5) end-of-life care/dying support in pandemics, (6) care after death in pandemics, (7) maintaining palliative care and (8) integration of palliative care. In a first step, the literature was coded deductively according to the coding guide of the expert workshop, since these eight key topics were the basis for the recommendations for action. Whenever literature emerged that was not included in the coding guide but was still relevant, the coding guide was expanded inductively (e.g., telemedicine). 10% of the included articles were double-coded to ensure the reliability of the extracted results. Furthermore, each article was additionally assessed for recommendations for action or best practice examples that can be applied in palliative and end-of-life care. In a second step, a summary content analysis according to Mayring (Reference Mayring2003) was conducted inductively, which led to a synthesis of the main aspects and challenges highlighted in the results.

Results

Description of studies

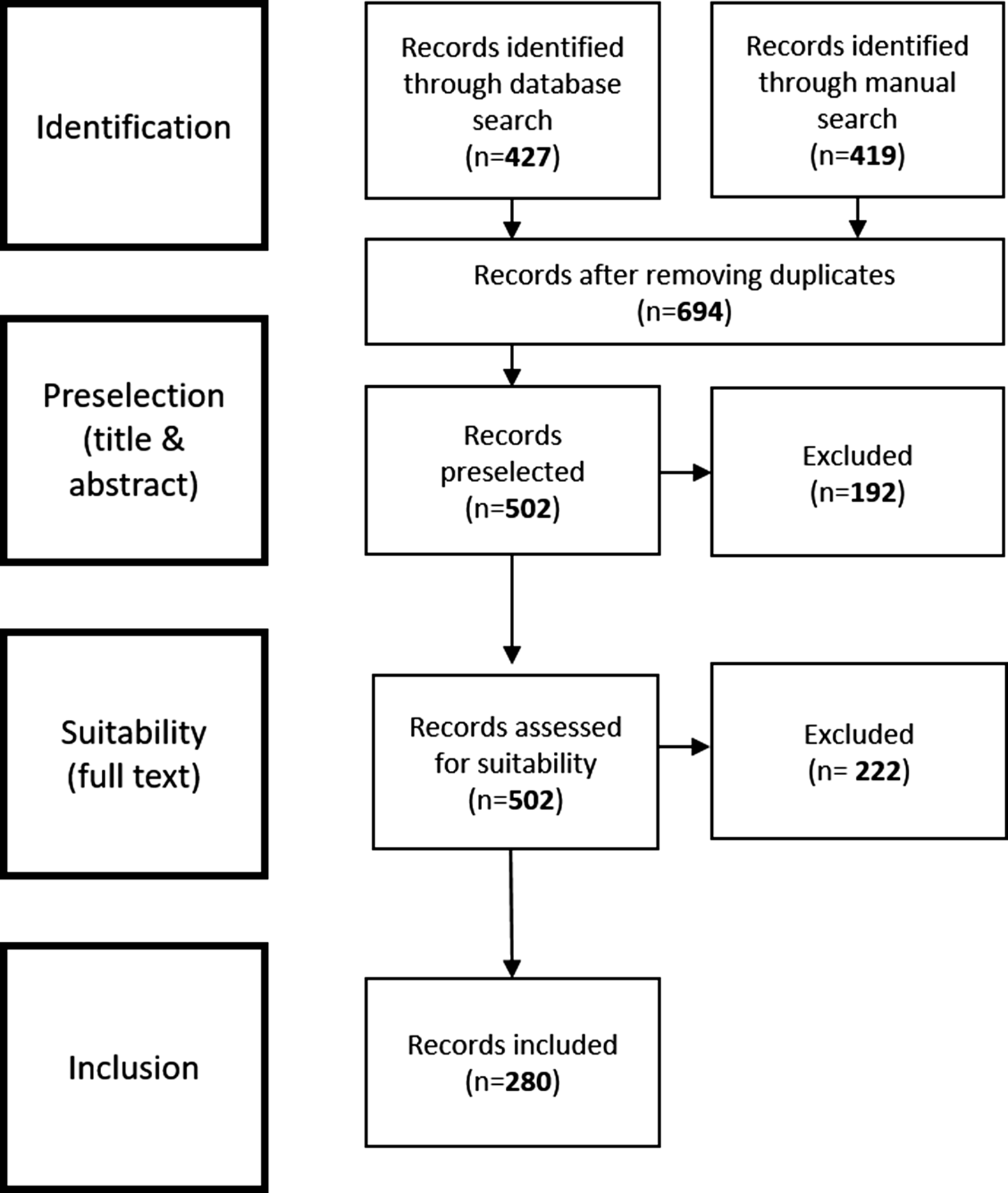

The search in MEDLINE (PubMed) yielded 427 studies. Additionally, 419 articles were added through manual search. After removing 152 duplicates, 694 articles were screened, and 192 articles were excluded according to exclusion criteria. A total of 502 articles were retained for full-text review, followed by the exclusion of further 222 articles. Overall, 280 articles were included in qualitative data extraction (Figure 1). They could be categorized in mainly special/fast-tracked articles (34%) and opinion papers/viewpoints/ commentaries/perspectives (19%), followed by reports/statement papers (14%), editorials (9%), and letters to the editor (6%). A total of 21 original articles and 9 reviews were included, 7 blog posts/website articles, as well as three interviews, one book section, and one protocol paper.

Fig. 1. Flowchart about the study selection.

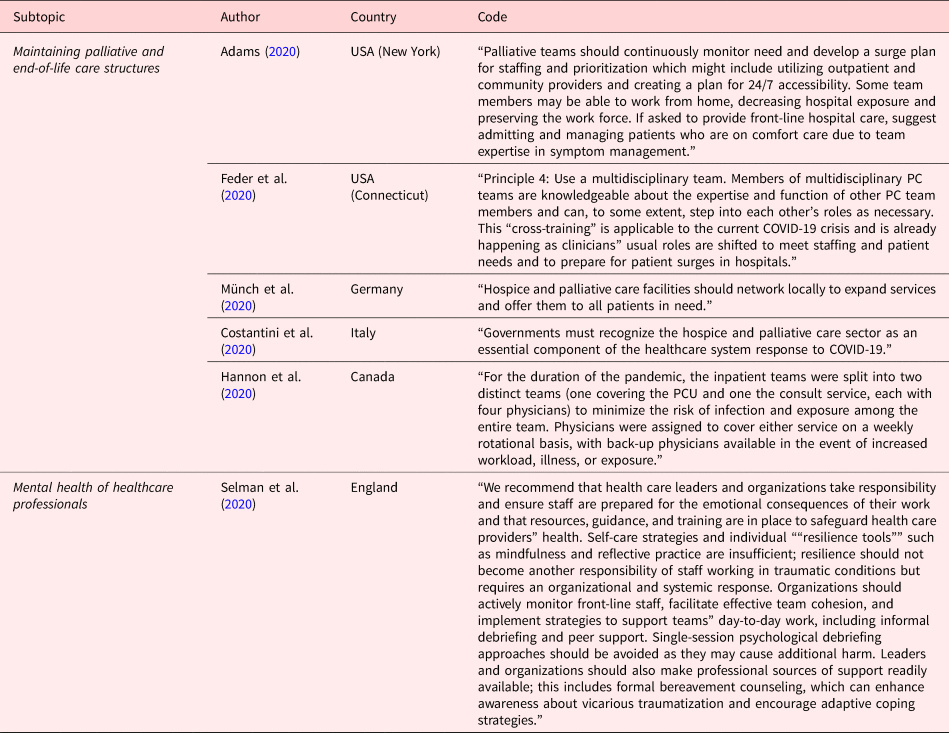

Overall, three main aspects and challenges could be identified through the analysis: maintaining palliative and end-of-life care structures despite limiting physical contact, supporting patients and relatives, and enabling contact and integrating specialist palliative care into other settings. The following sections reflect these themes in more detail. For this purpose, text passages with similar content have been summarized. Illustrative codes are shown in Tables 1–3.

Table 1. Illustrative quotes: maintaining palliative and end-of-life care structures

Table 2. Illustrative quotes: supporting patients and relatives and enabling contact

Table 3. Illustrative quotes: Integration of specialist palliative care into other settings

Maintaining palliative and end-of-life care structures

Due to the necessary reduction of physical contact, it was challenging for palliative and end-of-life care providers to maintain their daily work. In addition, in some cases, the numbers of infected patients have increased dramatically and parts of the teams have also been infected and were unable to work (Blinderman et al., Reference Blinderman, Adelman and Kumaraiah2020; Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Maddocks and Etkind2020; Schoenmaekers et al., Reference Schoenmaekers, Hendriks and van den Beuken-van Everdingen2020). Therefore, services must be flexible, adapt, and change their organization and work schedules as needed (Nevzorova, Reference Nevzorova2020). Home visits must be limited to those who actually need care and cases should be shared with colleagues in order to make better decisions (Nevzorova, Reference Nevzorova2020; Valenti, Reference Valenti2020). Frequent testing of the staff is recommended (Szczerbińska, Reference Szczerbińska2020) as well as designating one single professional who does in-person visits in the community setting (Tran et al., Reference Tran, Lai and Salah2020). Furthermore, hospice and palliative care facilities should network locally to expand their services and offer them to all patients in need (Boufkhed et al., Reference Boufkhed, Namisango and Luyirika2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020). As multidisciplinary teams are common in palliative care, team members can to some extent step into other roles if necessary, to compensate for shortfalls (Feder et al., Reference Feder, Akgün and Schulman-Green2020). Another option in resource-limited settings might be, to shift certain tasks from highly trained clinicians to those with limited training, to save costs and resources, but basic training should be a requirement (Knights et al., Reference Knights, Knights and Lawrie2020; Lopez et al., Reference Lopez, Finuf and Marziliano2021). Healthcare teams can be supported by maintaining an adequate patient-to-staff ratio and ensuring frequent breaks (Mottiar et al., Reference Mottiar, Hendin and Fischer2020). Providing and ensuring work-relevant information and the distribution of responsibility in order to keep additional workload low are essential (Hower et al., Reference Hower, Pfaff and Pförtner2020).

Healthcare institutions should develop a response plan for pandemics (Boufkhed et al., Reference Boufkhed, Harding and Kutluk2021) like COVID-19 with the domains staff, stuff, space, and system to ensure high-quality palliative care delivery for patients and relatives and attend to the needs of non-palliative care professionals as they care for infected patients (American Geriatrics Society, 2020; Sese et al., Reference Sese, Makhoul and Hoeksema2020). Policies and protocols that impact physical and psychological safety (e.g., PPE, physically distanced workspaces, time for recovery from vicarious trauma, and compassion fatigue) should be regularly assessed and adjusted (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Peck and Humphreys2020). In this context, it is crucial to ensure the availability (responsibility of individual governments) (Nyatanga, Reference Nyatanga2020; Valenti, Reference Valenti2020), training in and use of PPE for staff in all palliative care settings [Agar, Reference Agar2020; Alhalabi and Subbiah, Reference Alhalabi and Subbiah2020; Bern-Klug and Beaulieu, Reference Bern-Klug and Beaulieu2020; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Peck and Humphreys2020; Cohen and Tavares, Reference Cohen and Tavares2020; Fausto et al., Reference Fausto, Hirano and Lam2020; GovScot, 2020; Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Schoenherr and Elia2020; Kluger et al., Reference Kluger, Vaughan and Robinson2020; Mehta and Smith, Reference Mehta and Smith2020; Mottiar et al., Reference Mottiar, Hendin and Fischer2020; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Moine and Engels2020; Nevzorova, Reference Nevzorova2020; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Grant and Detering2020; Task Force in Palliative Care (PalliCovidKerala), 2020; Yardley and Rolph, Reference Yardley and Rolph2020]. To achieve this, PPE should be stockpiled for palliative care providers in long-term care and community settings (Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020).

Alongside clinical staff, chaplains should continue to work and certified chaplain interventions should be offered where available (Bajwah et al., Reference Bajwah, Wilcock and Towers2020; Bolt et al., Reference Bolt, van der Steen and Mujezinović2020; Ferrell et al., Reference Ferrell, Handzo and Picchi2020; Lawrie and Murphy, Reference Lawrie and Murphy2020). Therefore, if possible, a partnership with local spiritual counselors willing to visit patients face-to-face or virtually should be arranged (Schoenmaekers et al., Reference Schoenmaekers, Hendriks and van den Beuken-van Everdingen2020). Students (of social work) (Bern-Klug and Beaulieu, Reference Bern-Klug and Beaulieu2020) or volunteers who can provide psychological, psychosocial, and bereavement support by using digital technology or telephones can be employed (Cripps et al., Reference Cripps, Etkind and Bone2020; Fausto et al., Reference Fausto, Hirano and Lam2020; Cheng, Reference Cheng2021; Lopez et al., Reference Lopez, Finuf and Marziliano2021).

In the home care setting, family caregivers should be empowered to participate in providing care and be enabled to manage care with remote advice and support from community palliative care services (WHO, 2018; Chidiac et al., Reference Chidiac, Feuer and Naismith2020). Furthermore, they can be trained in the administration of medication at home to reduce avoidable hospital stays (Chidiac et al., Reference Chidiac, Feuer and Naismith2020; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Maynard and Lyons2020; Schoenmaekers et al., Reference Schoenmaekers, Hendriks and van den Beuken-van Everdingen2020).

Mental health of healthcare professionals

Staff should be offered special psychological support (Krishna et al., Reference Krishna, Neo and Chia2020; Szczerbińska, Reference Szczerbińska2020) and regular supervision to prevent burnout (Downar and Seccareccia, Reference Downar and Seccareccia2010; Nouvet et al., Reference Nouvet, Sivaram and Bezanson2018; WHO, 2018; Krakauer et al., Reference Krakauer, Daubman and Aloudat2019; Browne et al., Reference Browne, Roy and Phillips2020; Chidiac et al., Reference Chidiac, Feuer and Naismith2020; Hendin et al., Reference Hendin, La Rivière and Williscroft2020; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Beattie and Geller2020; Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Schoenherr and Elia2020; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Ekström and Currow2020; Boufkhed et al., Reference Boufkhed, Harding and Kutluk2021; Varani et al., Reference Varani, Ostan and Franchini2021). Peer-support (telephone or virtual) and informal debriefing to support teams’ day-to-day work should be implemented (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Peck and Humphreys2020; Mehta and Smith, Reference Mehta and Smith2020; Pattison, Reference Pattison2020; Schoenherr et al., Reference Schoenherr, Cook and Peck2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020). “Palliative care provider groups” should be formed to supply mutual support and coverage if a team member becomes overwhelmed by the situation (Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020; Mehta and Smith, Reference Mehta and Smith2020). Increased collaboration can decrease feelings of loss of control and minimize trauma response in teams (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Peck and Humphreys2020). Another important aspect is to recognize the hard work of staff in concrete ways (Bern-Klug and Beaulieu, Reference Bern-Klug and Beaulieu2020), ensure resilience (Etkind et al., Reference Etkind, Bone and Lovell2020), and focus on wellness and self-care (Hannon et al., Reference Hannon, Mak and Al Awamer2020). Therefore, resources for self-care and coping should be created, formalized, and disseminated (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Peck and Humphreys2020), including healthy food, enough sleep, social connections, and limiting news media (Kluger et al., Reference Kluger, Vaughan and Robinson2020).

Supporting patients and relatives and enabling contact

The restrictions on physical contact and the associated limitations on visits have led to great distress for all those involved. Therefore, patients and relatives must be supported and touch points need to be ensured as much as possible.

Physical face-to-face visits

It is necessary to continue to allow physical visits, even if in limited form (e.g., only one person for a limited time after having determined that the relative has no symptoms or infection) (Estella, Reference Estella2020; Lawrie and Murphy, Reference Lawrie and Murphy2020; Nevzorova, Reference Nevzorova2020). This is especially important for dying patients, as it has a great impact on the subsequent bereavement and processing of death (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Turnbull and Oppenheim2020; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Ekström and Currow2020; Mercadante, Reference Mercadante2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020). Family members should be allowed to visit deteriorating patients (Guessoum et al., Reference Guessoum, Moro and Mallet2020; Halek et al., Reference Halek, Reuther and Schmidt2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020). If it is not possible, it should be explicitly explained to the caring relatives that the patient will be adequately accompanied by staff (ÖGARI, 2020). It should not be forgotten that hospice workers and volunteers are also a crucial part of the circle of visitors to support patients and families (DGP, 2020).

Appropriate visiting concepts, including safety measures, should be developed and used in the institutions (DGP, 2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Moine and Engels2020). It is important to communicate in an open way what visitor regulations are in place and why. Therefore, institutions should provide information about their “pandemic policies” on their website and guide patients and relatives through internal processes and regulations (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Turnbull and Oppenheim2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020). Furthermore, evidence-based interventions, like rapid COVID-19 testing, tracing, and isolating cases can be established to avoid infections in healthcare institutions and to enable contact (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Broden and Meyer2020; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Moine and Engels2020).

Personal protective equipment

A frequent recommendation to enable visits is to include the provision of PPE to relatives and the development and provision of training on the appropriate use (Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020; Bear et al., Reference Bear, Simpson and Angland2020; Bern-Klug and Beaulieu, Reference Bern-Klug and Beaulieu2020; Eriksen et al., Reference Eriksen, Grov and Lichtwarck2020; Estella, Reference Estella2020; Hendin et al., Reference Hendin, La Rivière and Williscroft2020; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Ekström and Currow2020; Kent et al., Reference Kent, Ornstein and Dionne-Odom2020; Krones et al., Reference Krones, Meyer and Monteverde2020; Mercadante, Reference Mercadante2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020). Family caregivers should be considered when distributing PPE to protect themselves when caring for infected patients at home (Kent et al., Reference Kent, Ornstein and Dionne-Odom2020). PPE allows staff members to assist the patient during their last hours (Mottiar et al., Reference Mottiar, Hendin and Fischer2020), which reduces the risk of patients dying alone in isolation (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Johnson and Wynia2020).

Goals of care discussion/advance care planning

It is essential to be in contact with the family if the patient cannot express himself, e.g., with regard to goals of care discussions (Eriksen et al., Reference Eriksen, Grov and Lichtwarck2020; Kluger et al., Reference Kluger, Vaughan and Robinson2020). Goals of care discussions/advance care planning (GoC/ACP) and patient autonomy emerged to be an even more important topic during pandemic times.

The consensus of the synthesized literature is that GoC /ACP needs to be updated or created, especially for seriously ill people, to prevent triage discussions and to assign a specific contact person for each patient if possible. This is especially the case for patients who are older or suffer from advanced chronic diseases and patients that live in community and nursing homes/long-time care settings (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Johnson and Wynia2020; Adams, Reference Adams2020; Alhalabi and Subbiah, Reference Alhalabi and Subbiah2020; Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020; Bajwah et al., Reference Bajwah, Wilcock and Towers2020; Battisti et al., Reference Battisti, Mislang and Cooper2020; Bern-Klug and Beaulieu, Reference Bern-Klug and Beaulieu2020; Borasio et al., Reference Borasio, Gamondi and Obrist2020; Brighton and Evans, Reference Brighton and Evans2020; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Peck and Humphreys2020; Clarfield et al., Reference Clarfield, Dwolatzky and Brill2020; Cooper and Bernacki, Reference Cooper and Bernacki2020; Desai et al., Reference Desai, Kamdar and Mehra2020; Estella, Reference Estella2020; Fadul et al., Reference Fadul, Elsayem and Bruera2020; Flint and Kotwal, Reference Flint and Kotwal2020; Gillessen and Powles, Reference Gillessen and Powles2020; GovScot and SPCPA, 2020; Hendin et al., Reference Hendin, La Rivière and Williscroft2020; Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Lovick and Polak2020; Inzitari et al., Reference Inzitari, Udina and Len2020; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Ekström and Currow2020; Kamal et al., Reference Kamal, Casarett and Meier2020; Kent et al., Reference Kent, Ornstein and Dionne-Odom2020; Knights et al., Reference Knights, Knights and Lawrie2020; Kotze and Roos, Reference Kotze and Roos2020; Kunz and Minder, Reference Kunz and Minder2020; Lawrie and Murphy, Reference Lawrie and Murphy2020; Michels and Heppner, Reference Michels and Heppner2020; Mohile et al., Reference Mohile, Blakeley and Gatson2020; Moore, Reference Moore2020; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Sampson and Kupeli2020; Mottiar et al., Reference Mottiar, Hendin and Fischer2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020; NHS, 2020; Núñez et al., Reference Núñez, Madison and Schiavo2020; Peate, Reference Peate2020; Petriceks and Schwartz, Reference Petriceks and Schwartz2020; Raftery et al., Reference Raftery, Lewis and Cardona2020; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Grant and Detering2020; Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Ferrell and Wiencek2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020; Sieber, Reference Sieber2020; Spicer et al., Reference Spicer, Chamberlain and Papa2020; Szczerbińska, Reference Szczerbińska2020; Task Force in Palliative Care (PalliCovidKerala), 2020; Ting et al., Reference Ting, Edmonds and Higginson2020; Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Wladkowski and Gibson2020; Weinkove et al., Reference Weinkove, McQuilten and Adler2020; WHO, 2020). If possible technical possibilities (e.g., telecommunication) can be used for GoC /ACP, to keep the risk of infection low for all involved (Mehta and Smith, Reference Mehta and Smith2020; Lopez et al., Reference Lopez, Finuf and Marziliano2021).

Every inpatient should have a treatment escalation plan (control for patient, relatives, and healthcare workers) so that treatment decisions do not have to be made at short notice in a crisis (Downar and Seccareccia, Reference Downar and Seccareccia2010; Clarfield et al., Reference Clarfield, Dwolatzky and Brill2020). Building a therapeutic relationship is very important (Mottiar et al., Reference Mottiar, Hendin and Fischer2020) and patients have to be involved in decisions. If this is not possible, the clinicians should rely on relatives (shared-decision-making between team, patient, and relatives) (Eriksen et al., Reference Eriksen, Grov and Lichtwarck2020; Feder et al., Reference Feder, Akgün and Schulman-Green2020; Gaur et al., Reference Gaur, Pandya and Dumyati2020; Koffman et al., Reference Koffman, Gross and Etkind2020; Milano, 2020; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Tavares and Tzanno-Martins2020). Already existing assessment tools should be used to support decisions and can be included in GoC/ACP discussions with patients as well (Fiorentino et al., Reference Fiorentino, Pentakota and Mosenthal2020; Lapid et al., Reference Lapid, Koopmans and Sampson2020; McIntosh, Reference McIntosh2020). The patient's category status in the medical record should be updated accordingly (Hendin et al., Reference Hendin, La Rivière and Williscroft2020). Patients and relatives should be informed openly and honestly about the consequences and risks (infection/restricted visiting arrangements) that can result from a hospital stay (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Deodhar and Chaturvedi2020).

Healthcare systems can cooperate with the home care setting to ensure that primary care providers create awareness of GoC/ACP and that all can offer basic palliative care goals of care and symptom control (Essien et al., Reference Essien, Eneanya and Crews2020; Lopez et al., Reference Lopez, Finuf and Marziliano2021). The crisis could offer a chance to discuss GoC/ACP more openly in the population and to increase death literacy (Lapid et al., Reference Lapid, Koopmans and Sampson2020).

Communication in times of pandemics

All rules of communication that exist in palliative care continue to apply (Gibbon et al., Reference Gibbon, GrayBuck and Mehta2020; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Tavares and Tzanno-Martins2020; Schlögl and Jones, Reference Schlögl and Jones2020). Additionally, a COVID-19 specific language should be used (Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Abrukin and Blinderman2020) (e.g., “COMMUNICoVID” — How to communicate with families living in complete isolation) (Mistraletti et al., Reference Mistraletti, Gristina and Mascarin2020) and it is strongly recommended to encourage palliative care providers to honestly communicate the clinical uncertainty (e.g., of the COVID-19 trajectory) to families and patients. It is critical to provide transparent medical care, appropriate support, and counseling (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Rome and Constanza2020). Staff should be made aware of barriers resulting from communicating with patients in PPE (especially with masks/face shields) and trained in overcoming them (Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020) (e.g., pinning photos of their faces on the PPE to humanize themselves) (Brown-Johnson et al., Reference Brown-Johnson, Vilendrer and Heffernan2020; Reidy et al., Reference Reidy, Brown-Johnson and McCool2020).

Telecommunication/telemedicine

Recently, communication has increasingly taken place via telephone and digital/virtual media to maintain palliative and end-of-life care. A few points should be noted when using electronic devices in healthcare. The equipment used has to be disinfected regularly (Cormi et al., Reference Cormi, Chrusciel and Laplanche2020). Staff taking care of patients with serious COVID-19 infections should receive training in online clinician–family communication (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Ekström and Currow2020) and needs training in online communication (e.g., Vital Talk COVID-19 communication guides) (Gray and Back, Reference Gray and Back2020). Contact with the family should be made at least once a day (Adams, Reference Adams2020; Bajwah et al., Reference Bajwah, Wilcock and Towers2020; Hart et al., Reference Hart, Turnbull and Oppenheim2020; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Ekström and Currow2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020), preferably by the same person, possibly by email, so that the relatives are informed about the situation (Milano, 2020). Videophone communication should be preferred if possible, especially when breaking bad news (Alhalabi and Subbiah, Reference Alhalabi and Subbiah2020; Hart et al., Reference Hart, Turnbull and Oppenheim2020). There are also patients or families for whom online communication is not suitable because they are too ill or they do not have the technical possibilities. They should rather be contacted by telephone or be prioritized for personal contact (Kent et al., Reference Kent, Ornstein and Dionne-Odom2020).

Virtual visits

Virtual visits can be used, when face-to-face communication is not essential, to fit social distancing rules or when people are in quarantine. Virtual visits are very helpful when urgent decisions are necessary, but it is not appropriate to talk on the phone or when a personal visit would cause a delay or to prevent unnecessary use of PPE (Fausto et al., Reference Fausto, Hirano and Lam2020; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Gannon and Palfrey2020). Virtual contacts should be facilitated and daily updates should be organized even when the patient is not able to talk (Krakauer et al., Reference Krakauer, Daubman and Aloudat2019; Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Johnson and Wynia2020; Chidiac et al., Reference Chidiac, Feuer and Naismith2020; Cooper and Bernacki, Reference Cooper and Bernacki2020; Curley et al., Reference Curley, Broden and Meyer2020; Farnood and Johnston, Reference Farnood and Johnston2020; Guessoum et al., Reference Guessoum, Moro and Mallet2020; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Beattie and Geller2020; Knights et al., Reference Knights, Knights and Lawrie2020; Mayland et al., Reference Mayland, Harding and Preston2020; Mehta and Smith, Reference Mehta and Smith2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020; Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Abrukin and Blinderman2020; Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Ferrell and Wiencek2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020; Ting et al., Reference Ting, Edmonds and Higginson2020; Yardley and Rolph, Reference Yardley and Rolph2020; Pahuja and Wojcikewych, Reference Pahuja and Wojcikewych2021). This could be provided by additional staff (e.g., students, retired professionals) (Chidiac et al., Reference Chidiac, Feuer and Naismith2020). Therefore, structures for use of telecommunication should be set up (Feder et al., Reference Feder, Akgün and Schulman-Green2020; Gibbon et al., Reference Gibbon, GrayBuck and Mehta2020; Kent et al., Reference Kent, Ornstein and Dionne-Odom2020; Perrone et al., Reference Perrone, Zerbo and Bilotta2020; Schoenherr et al., Reference Schoenherr, Cook and Peck2020), while being cautious if it creates stress in actively dying patients (Fusi-Schmidhauser et al., Reference Fusi-Schmidhauser, Preston and Keller2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020). Through virtual visits, consultations [including symptom control (Kent et al., Reference Kent, Ornstein and Dionne-Odom2020) like monitoring opioid use (Adhikari et al., Reference Adhikari, Gupta and Sharma2020)] in clinics or medical offices can be reduced and thus lower the risk of infection (Perrone et al., Reference Perrone, Zerbo and Bilotta2020). In general, it is important to humanize technology and providers should prepare the family prior to the conference for what they may see. Furthermore, naming everyone in the room and how they are connected, explaining how the patient is being monitored and have guidance on what to say is helpful. Regular reassurance and check-ins should be provided. Pitfalls of technology (setting expectations, having a back-up plan, considering a test call) and elements of physical and human contact (singing favorite songs, having the family watch elements of comforting care such as holding the patient's hand, sharing favorite stories) should be considered (Ritchey et al., Reference Ritchey, Foy and McArdel2020).

There is emerging evidence on the utility of telemedicine in the provision of palliative care (Fadul et al., Reference Fadul, Elsayem and Bruera2020). However, adequate preparation and technical expertise are needed for an effective implementation into acute care settings. Palliative care and hospice teams will need to be proactive in identifying, implementing, and training on the most suitable remote platform to deliver services to patients and families (Creutzfeldt et al., Reference Creutzfeldt, Schutz and Zahuranec2020; Fadul et al., Reference Fadul, Elsayem and Bruera2020). It is crucial to ensure good WIFI connection and communication technology infrastructure (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Schoenherr and Elia2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020), to support and train staff in technology use (Hower et al., Reference Hower, Pfaff and Pförtner2020), and to organize information and data flow (Mody and Cinti, Reference Mody and Cinti2007; Behrens and Naylor, Reference Behrens and Naylor2020; Boufkhed et al., Reference Boufkhed, Namisango and Luyirika2020; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Peck and Humphreys2020; Hanratty et al., Reference Hanratty, Burton and Goodman2020; Hower et al., Reference Hower, Pfaff and Pförtner2020; Knights et al., Reference Knights, Knights and Lawrie2020). Governments should support digital education for aged care and on communication technology infrastructure, digital proficiency of staff and patients, and the provision of tech staff (Siette et al., Reference Siette, Wuthrich and Low2020). Furthermore, they should establish guidance (Rubinelli et al., Reference Rubinelli, Myers and Rosenbaum2020), e.g., on balancing data security/privacy and use of communication technology (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Turnbull and Oppenheim2020).

Care after death/bereavement support

Virtual bereavement counseling and support groups should be provided to relatives (Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020; Hado and Friss Feinberg, Reference Hado and Friss Feinberg2020). This might help coping with remote send-offs such as funeral live-streaming and saying goodbye via video chat (Frydman et al., Reference Frydman, Choi and Lindenberger2020; Moore, Reference Moore2020; Núñez et al., Reference Núñez, Madison and Schiavo2020). Relatives could be encouraged to express grief online, via telephone, letters, or videos and/or have online funerals (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Francis and Brown2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020). It is suggested to have a proper funeral after the pandemic or have a commemoration at home. Staff members can also provide an image of the deceased ones’ faces to the relatives (with permission) for better coping with bereavement (Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020).

Integration of specialist palliative care into other settings

The last but equally important aspect is the support of other clinical areas and settings by specialist palliative care teams. There is a necessity for palliative care to be available across different units, where patients at the highest risk reside (Arya et al., Reference Arya, Buchman and Gagnon2020). Palliative care delivery will frequently need to be undertaken by primary care teams under the guidance of specialist palliative care services (Davies and Hayes, Reference Davies and Hayes2020; Ferguson and Barham, Reference Ferguson and Barham2020; Krishna et al., Reference Krishna, Neo and Chia2020; Petriceks and Schwartz, Reference Petriceks and Schwartz2020; Weinkove et al., Reference Weinkove, McQuilten and Adler2020). Every clinician with palliative care experience should be identified for providing (online) education sessions for primary care staff to coach symptom management and end-of-life care (Downar and Seccareccia, Reference Downar and Seccareccia2010; Knights et al., Reference Knights, Knights and Lawrie2020; Lai et al., Reference Lai, Wang and Ko2020; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Maynard and Lyons2020; NHS, 2020; Radbruch et al., Reference Radbruch, Knaul and de Lima2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020). Therefore, it is crucial to develop standardized order sheets and protocols, including order sets for end-of-life symptom management and continuous palliative sedation therapy for a particular use by non-specialist physicians (Downar and Seccareccia, Reference Downar and Seccareccia2010; Bowman et al., Reference Bowman, Back and Esch2020; Cripps et al., Reference Cripps, Etkind and Bone2020; Hannon et al., Reference Hannon, Mak and Al Awamer2020). The developed plans and palliative care assessments need to be clear and simple to understand to achieve maximum relief of symptoms (Fusi-Schmidhauser et al., Reference Fusi-Schmidhauser, Preston and Keller2020). Involved allied healthcare workers like social workers and spiritual care staff can provide psychosocial support and bereavement counseling (Downar and Seccareccia, Reference Downar and Seccareccia2010; WHO, 2018; Etkind et al., Reference Etkind, Bone and Lovell2020). Furthermore, non-specialist staff in all different clinical areas has to be coached in primary palliative care communication skills (e.g., asking about hopes, worries) (Desai et al., Reference Desai, Kamdar and Mehra2020; Gibbon et al., Reference Gibbon, GrayBuck and Mehta2020; Hannon et al., Reference Hannon, Mak and Al Awamer2020; Mottiar et al., Reference Mottiar, Hendin and Fischer2020; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Moine and Engels2020; Rajagopal, Reference Rajagopal2020; Sese et al., Reference Sese, Makhoul and Hoeksema2020; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Deodhar and Chaturvedi2020).

Triage/ethic committees

Each hospital that does not have an ethics committee ought to organize one in case of triage. Complex triage decisions should never rest on a single person but involve an interdisciplinary team (e.g., existing of an intensive care physician, an internist, and a palliative care specialist) (Borasio et al., Reference Borasio, Gamondi and Obrist2020; Mercadante, Reference Mercadante2020; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Kaye and Mody2020; Obata et al., Reference Obata, Maeda and Rizk2020).

Primary care staff

There are special recommendations for primary care staff (including ICUs and emergency departments). For these teams, it is relevant to embed palliative care into their department and to organize regular rounds to support and promote appropriate consultation (Adams, Reference Adams2020) and to screen for patients with palliative care needs (Adams, Reference Adams2020; Fusi-Schmidhauser et al., Reference Fusi-Schmidhauser, Preston and Keller2020; Gibbon et al., Reference Gibbon, GrayBuck and Mehta2020; Haydar et al., Reference Haydar, Lo and Goyal2020; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Abrukin and Flores2020). This includes peer education and support (Mody and Cinti, Reference Mody and Cinti2007; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Peck and Humphreys2020; Hado and Friss Feinberg, Reference Hado and Friss Feinberg2020; Hower et al., Reference Hower, Pfaff and Pförtner2020; Rim et al., Reference Rim, Kelly and Meletio2020) as well as engagement with institutional crisis response teams to ensure palliative care needs are incorporated into system-level response plans (Feder et al., Reference Feder, Akgün and Schulman-Green2020; Münch et al., Reference Münch, Müller and Deffner2020; Sese et al., Reference Sese, Makhoul and Hoeksema2020; Pahuja and Wojcikewych, Reference Pahuja and Wojcikewych2021). Pathways can be identified for rapid consultation and involvement of palliative care teams (Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Ferrell and Wiencek2020). The integration of palliative care into different settings and the involvement of specialists helps not only to provide essential care to patients but also to reduce the emotional burden of healthcare workers being at frontline (Nevzorova, Reference Nevzorova2020).

System level

Governments must recognize the hospice and palliative care sector as an integral component of the healthcare systems’ response to pandemics (WHO, 2018; Costantini et al., Reference Costantini, Sleeman and Peruselli2020; Laxton et al., Reference Laxton, Nace and Nazir2020; Mercadante, Reference Mercadante2020; Salifu et al., Reference Salifu, Atout and Shivji2020) and the need for ongoing education and training offered to healthcare workers (WHO, 2018). Collaborative relationships between generalist and specialist providers of palliative care have to be developed and better understood to inform national policy and to evolve recommendations for service delivery during future pandemics (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Maynard and Lyons2020).

Discussion

In this scoping review, the relevant aspects of palliative and end-of-life care of severely ill and dying people and their relatives during pandemic times have been synthesized. As an overall result, three central aspects have emerged through the analysis: maintaining palliative and end-of-life care structures despite limiting physical contact, supporting patients and relatives, and enabling contact and integrating specialist palliative care into other settings.

The principles of palliative care aiming to increase the quality of life, support the patients and their families and friends, and allowing dying in dignity still apply to humanitarian crises such as the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. However, the restrictions imposed by the pandemic on health care systems and thus palliative care are challenging for professionals as they need to accept that elements taken for granted before the pandemic are not possible anymore like unrestricted visiting, physical contact, or direct patient contact. Even more, the use of PPE, often felt as distancing to the patients, is now the basis for any patient contact. However, the pandemic also provides an opportunity for the development of palliative care. The need for palliative and end-of-life care becomes evident in a pandemic which is reflected in the first topic of this scoping review, maintaining palliative and end-of-life care structures despite limiting physical contact. Palliative care services and teams need to adapt to the current situation and partially find new ways of working. Health care providers and decision makers should support existing services rather than questioning them. Working under these constraints is demanding and many professionals suffer from mental health problems for which health care leaders and organizations need to take responsibility (Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020).

The second aspect, supporting patients and relatives, lies in the very heart of palliative care. Providing symptom management and support for dying people and their relatives should be paramount irrespective of the setting and the underlying disease or infectious status. Key issue and cause of severe distress is the reduction of physical contact accompanied by strict visitor restrictions in inpatient settings. Patients and relatives need to be supported and contact between them should be allowed wherever possible.(Estella, Reference Estella2020; Lawrie and Murphy, Reference Lawrie and Murphy2020; Nevzorova, Reference Nevzorova2020). At the beginning of the pandemic, the provision of sufficient PPE had been a major logistical challenge, especially in the home care setting (Nyatanga, Reference Nyatanga2020; Valenti, Reference Valenti2020). However, the recent experience in many countries shows that there are meanwhile sufficient amounts of PPE in all settings. Consequently, relatives should be provided with PPE for visits to their loved ones (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Ekström and Currow2020). Virtual visits can be another solution (Fausto et al., Reference Fausto, Hirano and Lam2020; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Gannon and Palfrey2020), but the situation must be assessed individually, as virtual contact can be perceived as a burden for severely ill or dying patients (Fusi-Schmidhauser et al., Reference Fusi-Schmidhauser, Preston and Keller2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020). Especially in times of pandemics, open communication with patients and relatives is even more essential. This also relates to goals of care and advance care planning discussions to foster patient-centered care. The synthesized literature clearly underpins that they form an important basis for remaining able to act in times of scarce resources. Triage discussions and treatment that is not wanted by patients can thus be avoided especially in seriously ill, older people, or people who live in nursing homes/long-time care settings (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Sampson and Kupeli2020; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Chao and Sowden2020; Sieber, Reference Sieber2020). These discussions and conversations should be honest and direct (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Rome and Constanza2020). Nevertheless, the general rules of communication in palliative care still apply (Gibbon et al., Reference Gibbon, GrayBuck and Mehta2020; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Tavares and Tzanno-Martins2020; Schlögl and Jones, Reference Schlögl and Jones2020). Therefore, it is important to also train other non-specialist staff on the basics of palliative care communication skills (Desai et al., Reference Desai, Kamdar and Mehra2020; Gibbon et al., Reference Gibbon, GrayBuck and Mehta2020; Hannon et al., Reference Hannon, Mak and Al Awamer2020; Mottiar et al., Reference Mottiar, Hendin and Fischer2020; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Moine and Engels2020; Rajagopal, Reference Rajagopal2020; Sese et al., Reference Sese, Makhoul and Hoeksema2020; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Deodhar and Chaturvedi2020).

The third area covered by this review is the integration of specialist palliative care into other settings, to support other disciplines and identify patients in need of palliative care at an early stage. The call to integrate specialist palliative care even more into the health care system already existed before the pandemic. Basic knowledge on symptom management and communication is necessary in every health care setting caring for severely ill and dying patients. Specialist palliative care professionals need to further develop their advisory and teaching roles to foster the skills of other professionals and teach them palliative care principles. Primary carers (e.g., in ICUs and emergency departments) and palliative care teams in particular need to network and collaborate to ensure the best possible treatment for severely ill patients (Adams, Reference Adams2020).

Overall, every aspect mentioned has to be adapted individually to the context of each setting in different countries. To support this and to be prepared for future pandemics, we need to learn from each other and from the developed solutions.

Strength and limitations

A strength of this scoping review is the inclusion of a wide range of publications and aspects up to February 2021 in quite a dynamic time. Also, the qualitative approach of analyses of the publications’ content helped to capture all relevant topics. Limitations are the lack of quality appraisal of the included publications and the limitation to English and German articles. In addition, only one database was searched, leading to a particular risk that allied health literature was neglected. As the review is part of a wider project with very strict time limits, we did not have the resources to conduct a full systematic review. As we were mainly interested in the various aspects of palliative and end-of-life care, we felt a scoping review would better meet our circumstances.

What this study adds

This study adds an overview of relevant aspects and non-therapeutic recommendations in palliative and end-of-life care after one year into the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Only a very limited number of the included articles presented results from research studies. This is of course due to the limited time factor and the novelty of the global pandemic situation, but it also demonstrates that there are research gaps and enormous potentials to close them. Of particular interest are the long-term effects on the individuals involved, both patients and family members, as well as healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

The results of the scoping review indicate that besides the integration of advance care planning in every clinical area and setting, the further development and expansion of digitalization in the healthcare sector is needed and must continue in order to be able to offer telecommunication and telemedicine. Using electronic devices in communication is helpful in non-pandemic times as well and will be increasingly requested. It also supports a lively exchange between professionals, patients and relatives, e.g., in goals of care discussions. Therefore, infrastructure must be provided, but staff must also be trained in specific “online communication skills”. In addition and especially in order to provide sufficient advance care planning, every healthcare professional should have basic knowledge of palliative care, which must be trained across all relevant clinical disciplines. Finally, a national strategy for integrating palliative care in pandemic times should be developed in each country.

Author contributions

CB and STS obtained funding for PallPan. Concept and design of the review: CB, DG, EL, and STS. The analysis was carried out by DG, EL, SG, and MW. The synthesis was mainly performed by EL and DG. DG and EL wrote the manuscript with support from SG. SG, MW, STS, and CB critically reviewed the manuscript. CB supervised the project. All authors provided critical comments on drafts of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

PallPan is funded within the Network University Medicine by the German Ministry of Education and Research (Förderkennzeichen 01KX2021). The funding body has no role in the design of the study and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This was a secondary data analysis, which was based on published aggregate data. Neither informed consent to participate nor ethical approval is required.