Introduction

In the mid-1990s, the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders introduced serious illness as a potential traumatic stressor. The announcement of a life-threatening diagnosis, painful experiences, debilitating treatment side-effects and the knowledge of a poor prognosis can indeed be experienced as traumas, understood here as “life-altering” events that deeply challenge, even “shatter” people's sense of self and core beliefs (Janoff-Bulman, Reference Janoff-Bulman1992; World Health Organization, 1992; Mundy and Baum, Reference Mundy and Baum2004; Cordova et al., Reference Cordova, Riba and Spiegel2017; Tedeschi et al., Reference Tedeschi, Shakespeare-Finch and Taku2018). While illness-related traumas differ from those induced by natural or man-made disasters, insofar as they can be internal and repeated (multiple chronic stressors), empirical research suggests that individuals are likely to experience major psychological changes, whether negative or positive, in response to the trauma of illness (Sumalla et al., Reference Sumalla, Ochoa and Blanco2009; Swartzman et al., Reference Swartzman, Booth and Munro2017).

People with long-term illnesses are estimated to be two to three times more likely to experience psychological distress or mental health issues than the general population (Naylor et al., Reference Naylor, Parsonage and McDaid2012). Recent studies suggest that one in two cancer patients experiences high levels of psychological distress, and that up to a third of cancer patients or survivors experience posttraumatic stress disorder (Abbey et al., Reference Abbey, Thompson and Hickish2015; Arnaboldi et al., Reference Arnaboldi, Riva and Crico2017; Swartzman et al., Reference Swartzman, Booth and Munro2017; Mehnert et al., Reference Mehnert, Hartung and Friedrich2018). Similarly, posttraumatic disorders affect between 9% and 27% of intensive care survivors (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Bäckman and Capuzzo2007; Battle et al., Reference Battle, James and Bromfield2017; Hatch et al., Reference Hatch, Young and Barber2018; Askari Hosseini et al., Reference Askari Hosseini, Arab and Karzari2021), and up to 74% of people with HIV (Sherr et al., Reference Sherr, Nagra and Kulubya2011).

Overtime, the inner battles and struggles following trauma may instigate a process of transformative, positive psychological changes known as posttraumatic growth or PTG (Joseph and Linley, Reference Joseph and Linley2005; Calhoun and Tedeschi, Reference Calhoun and Tedeschi2013). In PTG theory, these changes may unfold in individuals’ sense of personal strength, how they relate to others, their openness to new possibilities in life, their appreciation of life, and their spirituality. To measure these, PTG theorists have developed the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI), which assesses changes in the five domains above and is, to date, the most common measure of growth. Studies using the PTGI indicate that growth is an important process for people with serious illness. For instance, between 10% and 73% of cancer patients experience moderate to high growth, as do 47% of heart disease survivors (Bluvstein et al., Reference Bluvstein, Moravchick and Sheps2013; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Kaminga and Dai2019).

Although PTG is understood as a process of positive cognitive and emotional transformation whereby individuals give deeper meaning and gain greater appreciation of life, rebuilding the shattered self entails sustained, confronting, difficult, and potentially distressing self-reflection (Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Hunt and Joseph2011; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Murphy and Regel2012). As such, PTG theory posits that positive and negative psychological responses to trauma are likely to coexist, and that some forms of distress may even act as “catalysts” for growth (Calhoun and Tedeschi, Reference Calhoun and Tedeschi1998). Such insight may explain inconsistent empirical links between PTG, psychological distress, and quality of life (Tanyi et al., Reference Tanyi, Mirnics and Ferenczi2020). Reviews reveal contrasting results between distress and growth: a negative association between PTG and posttraumatic stress disorder and depression for people with HIV (Rzeszutek and Gruszczyńska, Reference Rzeszutek and Gruszczyńska2018), but a positive one between PTG and stress for cancer patients (Marziliano et al., Reference Marziliano, Tuman and Moyer2020), for instance. Similarly, empirical studies suggest that the relationship between PTG and quality of life is complex and still ill-understood in people with serious illness — with results encompassing positive, negative, null, and curvilinear relations (Tomich and Helgeson, Reference Tomich and Helgeson2012).

In the posttraumatic stress and growth literature, more acutely perceived threats have been associated with heightened psychological responses, whether positive or negative (Cordova et al., Reference Cordova, Cunningham and Carlson2001; Holbrook et al., Reference Holbrook, Hoyt and Stein2001). As highlighted in a meta-analysis, stage 4 cancer patients experienced stronger positive links between posttraumatic stress and growth than less advanced patients, which led the authors to postulate that “the more an event is perceived as threatening [ … ] the more entrenched one will become in the rapid, cyclical process of growth and stress, leading to a stronger relationship between the two constructs” (Marziliano et al., Reference Marziliano, Tuman and Moyer2020). Against this backdrop, palliative care emerges as a particularly relevant setting to investigate PTG, as patients are likely to experience a heightened sense of vulnerability, being directly confronted with the threat of impending death (Casellas-Grau et al., Reference Casellas-Grau, Ochoa and Ruini2017).

To our knowledge, only two studies have focused on PTG in palliative care patients. One highlights positive links between growth and end of life dreams and visions (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Grant and Depner2020). The other, conducted by our research team, found positive associations between gratitude and growth (Althaus et al., Reference Althaus, Borasio and Bernard2018). However, key questions of PTG prevalence and associations with psychological distress and quality of life in palliative patients remain unanswered.

To fill this gap, this study investigates whether PTG is an empirically relevant concept for palliative care patients. To do so, we first assess PTG in palliative patients, in terms of prevalence and specific areas of growth. We then investigate associations between PTG and (i) psychological distress, exploring whether people faced with the heightened threat of advanced illness might experience co-occurring growth and distress; and (ii) quality of life, the most important outcome in palliative care, whose links with PTG in those with serious illness are still ill-understood.

Methods

This cross-sectional study deployed standardized, validated questionnaires to collect quantitative data about palliative care patients, as part of a wider research project examining gratitude at the end of life (Althaus et al., Reference Althaus, Borasio and Bernard2018).

Procedure and participants

This study was conducted at the Lausanne University Hospital, Switzerland. It was approved by the hospital's ethics committee. Recruitment took place between March 2015 and January 2016 at the palliative and supportive care service, which includes an inpatient unit, a consult team, a home care team, and an outpatient clinic. The palliative care team systematically identified eligible individuals, namely palliative care patients over 18 treated for a progressive disease reducing their life expectancy, who had been clinically stable for the past 24 h. People with cognitive or psychiatric disorders impairing their decision-making capacity and those with important communication issues were excluded. A researcher (independent from the healthcare team) visited eligible patients who agreed to be contacted for this study and informed them orally and in writing. She collected the written consent of those who agreed to participate and administered standardized questionnaires in face-to-face interviews.

Measures

Socio-demographic and medical assessments

We collected socio-demographic data on age, sex, nationality, mother tongue, civil status, education level, and occupation through face-to-face interviews. The healthcare team provided us with patients’ medical data, namely main diagnosis and health status assessed through the ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) Scale of Performance Status, which describes patients’ levels of functioning and autonomy in their daily activities and physical abilities — between 0 (“Fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction”) and 5 (“death”).

Posttraumatic growth: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI)

The PTGI consists of 21 items that each describe a potential change caused by a trauma on a 6-point Likert scale, between 0 (“I did not experience this change as a result of my crisis”) and 5 (“I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my crisis”) (Tedeschi and Calhoun, Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun1996). The questionnaire yields a total score (0–105, α = 0.89) and intermediate scores in five subscales: “relating to others” (0–35, α = 0.78), “new possibilities” (0–25, α = 0.73), “personal strength” (0–20, α = 0.77), “spiritual change” (0–10, α = 0.61), and “appreciation of life” (0–15; α = 0.61). Higher scores reflect higher levels of PTG. We used a validated French translation of the questionnaire (Lelorain et al., Reference Lelorain, Bonnaud-Antignac and Florin2010).

The PTGI is not a diagnostic instrument and lacks established cutoffs and reporting standards (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Kaminga and Dai2019). To examine and describe the levels of PTG experienced by our participants, we drew inspiration from a study on PTG in cancer survivors (Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Hoffmeister and Chang-Claude2011) and differentiated between no growth or low growth, moderate growth, and high to very high growth, as outlined in Table 1. Prior to administering the PTGI, we also sought to mitigate potential positivity bias by assessing overall, negative and positive subjective changes linked with the illness — through the questions: “Globally, to what extent would you say that your illness has negatively (Q1)/positively (Q2) changed your personality and/or your life?” (0–10).

Table 1. PTGI scores with corresponding degrees of growth

Quality of life: McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire – Revised (MQoL-r)

The 14-item questionnaire assesses the quality of life of people with life-threatening illnesses (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Sawatzky and Russell2017). It yields a total score (0–10, α = 0.87) and four subscales scores, addressing physical (0–10, α = 0.66), psychological (0–10, α = 0.85), existential (0–10, α = 0.57), and social quality of life (0–10, α = 0.71). An additional item assesses individuals’ overall, subjective quality of life. Higher scores reflect higher quality of life. The questionnaire was translated into French by the Canadian team who developed the MQoL-r.

Psychological distress: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The HADS consists of 14 items rated on a Likert scale yielding a total score (0–42; α = 0.73), a depression score (0–21; α = 0.73), and an anxiety score (0–21, α = 0.66) (Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983). Higher scores reflect higher levels of distress. The scale was validated in French (Razavi et al., Reference Razavi, Delvaux and Farvacques1989).

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to examine participants’ socio-demographic and medical characteristics and their levels of growth, psychological distress, and quality of life. Based on the PTGI results, we further assessed the prevalence and most salient dimensions of growth. Pearson correlations were performed to explore associations between PTG (PTGI total score), quality of life, and psychological distress. Finally, we performed linear regression to examine which factor(s) could predict growth (PTGI total and subscale scores), controlling for age, sex, education level, civil status, and health status. Given the exploratory nature of this study, we used backward elimination procedures to identify the model with the best predictive value — as there is less risk of making type II errors than with the stepwise and forward methods. We also performed a Bonferroni correction (for multiple comparisons) to limit potential type I errors due to multiple comparisons — with a significance level set at p = 0.01 since we have five subscales.

We established a minimum threshold of 10–15 observations for each predictor (Bressoux, Reference Bressoux2010). To manage missing data, we calculated quality of life and PTG scores using mean imputation, as long as there was no more than one missing item per subscale (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Sawatzky and Russell2017). For the HADS, we calculated subscale means if at least half of the items had been answered (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Fairclough and Fiero2016). Data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 24.

Results

Participants

The clinical team identified 164 patients as eligible for this study, 100 (61%) of whom were informed but did not participate, for the following reasons: unwilling to participate (26 patients), no longer a patient of the palliative care service (22), worsening psychological or cognitive problems (16), physical problems (15), emergence of other exclusion criteria (communication or not clinically stable) (11), deceased (7), and cannot be reached (3). Sixty-four patients (39%) agreed to participate, seven of whom did not provide any answer to the PTGI, and two of whom had more than one missing data per PTGI subscale. The 55 participants (34% of eligible patients) who completed the PTGI are included in this study. Their demographic and medical characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Participants’ demographic and medical characteristics (N = 55)

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

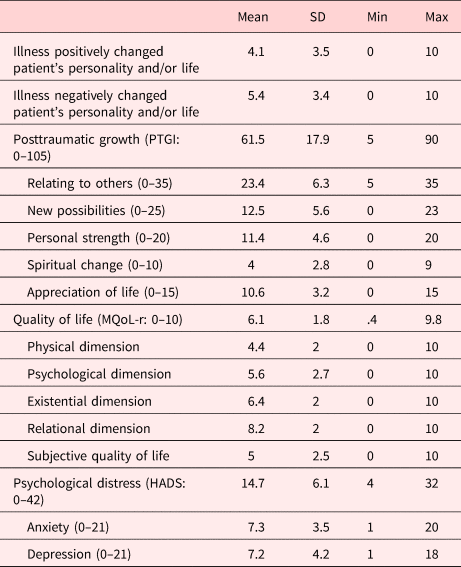

Descriptive analyses of PTG (including overall positive and negative illness-related changes), quality of life, and psychological distress

Considered in the light of possible score ranges, our participants’ overall mean scores reflect low to moderate levels of growth, moderate quality of life, and relatively low levels of psychological distress. They also reported moderate levels of both positive and negative changes on their personality and/or life linked with the illness (as detailed in Table 3).

Table 3. Participants’ levels of PTG, overall positive and negative changes linked with the illness, quality of life, and psychological distress (N = 55)

MQoL-r, McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire – Revised; PTGI, Posttraumatic Growth Inventory; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SD, Standard Deviation.

Prevalence of PTG

Twenty-four (44%) participants reported no to low growth (IC: 30.5–56.7%), 26 (47%) moderate growth (IC: 34.1–60.5%), and 5 (9%) high to very high growth (IC: 1.5–16.7%).

Most salient areas of growth

When standardizing mean scores to allow for meaningful comparison, participants scored highest in the areas “appreciation of life” (14.1/20; original ![]() $\bar{x}$ = 10.6 [0–15]) and “relating to others” (13.4/20; original

$\bar{x}$ = 10.6 [0–15]) and “relating to others” (13.4/20; original ![]() $\bar{x}$ = 23.4 [0–35]), followed by “personal strength” (11,4/20; same as original), “new possibilities” (10/20; original

$\bar{x}$ = 23.4 [0–35]), followed by “personal strength” (11,4/20; same as original), “new possibilities” (10/20; original ![]() $\bar{x}$ = 12.5 [0–25]), and “spiritual change” (8/20; original

$\bar{x}$ = 12.5 [0–25]), and “spiritual change” (8/20; original ![]() $\bar{x}$ = 4 [0–10]).

$\bar{x}$ = 4 [0–10]).

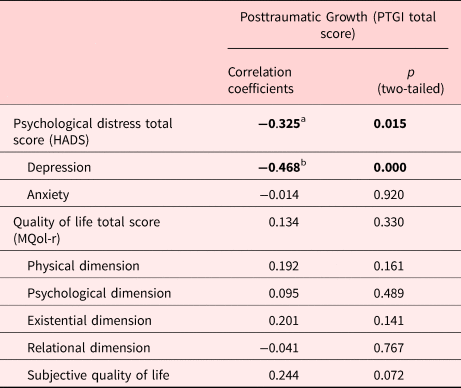

Bivariate associations of PTG with psychological distress and quality of life

Table 4 shows Person correlations between growth, psychological distress, and quality of life. We found significant negative correlations between PTG and psychological distress (total HADS score), and between PTG and depression (HADS depression score). There was no significant correlation with quality of life (total and subscale scores of the MQoL-r) or with anxiety.

Table 4. Pearson correlations

PTGI, Posttraumatic Growth Inventory; MQoL-r, McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire – Revised; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

a Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level.

b Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level.

Bivariate associations between positive and negative illness-related changes

Pearson correlation between reported positive and negative changes on patients’ lives and/or personalities was negative but not significant (r = −0.167, p = 0.228).

Multivariate associations of PTG with psychological distress and quality of life

We performed regression analyses on the PTGI total score and each PTGI area of growth in relation to psychological distress (HADS depression score and anxiety score) and quality of life (MQoL-r total score). The final model explains 21.9% of total variance for the PTGI total score, 40.2% of total variance in the area “appreciation of life,” 23.3% in “personal strength,” 17.4% in “new possibilities,” and 13.7% in “relating to others.” No significant model was found for “spiritual change.” As shown in Table 5, depression (HADS depression score) is the only variable associated with the PTGI (total score and subscales). It is significantly and negatively associated with the PTGI total score and with the areas “relating to others,” “personal strength,” and “life appreciation.”

Table 5. Final models from linear regression for the PTGI (total score and subscales)

CI, Confidence interval; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

The significance level is at p = 0.01 with Bonferroni correction.

Discussion

To investigate whether PTG is an empirically relevant concept for palliative care patients, this study's first aim was to assess PTG in terms of prevalence and areas of growth. We found that 44% of our participants experienced no growth or low growth, 47% moderate growth, and 9% high to very high growth. With 56% of palliative patients reporting moderate to very high PTG levels, our study reveals a prevalence level similar to that of cancer patients (46% to 73%), and higher than heart disease survivors (47%) (Bluvstein et al., Reference Bluvstein, Moravchick and Sheps2013; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Kaminga and Dai2019). Our results are particularly close to those of women with breast cancer (57–59%), adolescents and young adults with cancer (59%), and open heart surgery patients (57%) (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Kaminga and Dai2019). While PTG prevalence rates should be compared with caution, as different studies might use different cutoffs, over half of palliative patients reported experiencing significant positive changes following the trauma of their illness. About 1 in 10 of our patients experienced high to very high growth, suggesting that PTG is a process worthy of further consideration and exploration in palliative care.

With an overall PTGI mean score of 61.5, our participants experienced levels of growth similar to those of cancer survivors 3 years after diagnosis (61) and hospice patients who experienced end of life dreams and visions (64); significantly higher than non-dreaming hospice patients (50), terminal cancer patients (52), women with advanced breast cancer (44), and heart disease survivor (ranging 41–58); and lower than men with advanced cancer (76) (Mystakidou et al., Reference Mystakidou, Tsilika and Parpa2008, Reference Mystakidou, Parpa and Tsilika2015; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Shakespeare-Finch and Scott2012; Rand et al., Reference Rand, Cripe and Monahan2012; Bluvstein et al., Reference Bluvstein, Moravchick and Sheps2013; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Lin and Chen2015; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Grant and Depner2020). While our participants’ mean score is still classified as low (just under the 63 cutoff), it is located at the higher end of growth levels reported by those with serious illness.

Areas where participants experience the greatest levels of growth are “appreciation of life” and “relating to others,” mirroring the areas of positive changes identified by palliative hospice patients, patients with advanced cancer, and cancer survivors (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Gamblin and Geller2011; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Shakespeare-Finch and Scott2012; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Grant and Depner2020). As shown by a grounded theory study with breast cancer patient, serious illness can lead people to feel more grateful for and appreciate “the small, intangible things in life” (Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Weller-Newton and Shimoinaba2021). Indeed, appreciation, defined as acknowledging the value and meaning of something (event, person, behavior, or object) and feeling a positive emotional connection to it, is a core concept of gratitude (Adler and Fagley, Reference Adler and Fagley2005; Rusk et al., Reference Rusk, Vella-Brodrick and Waters2016), which is also strongly and positively linked with PTG, as shown in our previous publication (Althaus et al., Reference Althaus, Borasio and Bernard2018). Recognizing the fragility of life, some people also make a conscious decision to enjoy every moment they live; in the word of a participant: “No matter how long you live, what counts the most is how happy you are in this process” (Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Weller-Newton and Shimoinaba2021). Our findings further underline the importance of interpersonal relationships at the end of life, which were found to improve quality of life and give meaning to the lives of palliative patients (Stiefel et al., Reference Stiefel, Krenz and Zdrojewski2008; Fegg et al., Reference Fegg, Kogler and Brandstatter2010; Giovannetti et al., Reference Giovannetti, Pietrolongo and Giordano2016; Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Berchtold and Strasser2020).

The second aim of this study was to explore associations between PTG, psychological distress, and quality of life. Overall, our final model explained 21.9% of the PTG total score variance and between 13.7% and 40.2% of variance for single PTG areas. Our results indicate that PTG is linked with psychological distress in an ambivalent way, presenting a significant negative association with depression, but only a weak, non-significant association with anxiety. These findings partly echo results from a recent meta-analysis in oncology, with 45% of reviewed articles focusing on depression highlighting a negative association with PTG, against 25% of reviewed articles focusing on anxiety (Casellas-Grau et al., Reference Casellas-Grau, Ochoa and Ruini2017).

Such results suggest that moderate to very high growth is associated with lower levels of depression, possibly because those experiencing growth are able to adequately process past traumas and build a stronger, more positive sense of self and life narrative overtime. When considering the ensemble hypothesis on human cognitive abilities (Kellogg et al., Reference Kellogg, Chirino and Gfeller2020), depressive disorders are associated with excessively pessimistic explanatory styles and persistent negative rumination. Thereby, people tend to focus on and blame themselves for negative past experiences, leading to difficulties in imagining a positive future. Based on our results, we could hypothesize that experiencing PTG processes — gaining a greater appreciation of life or developing better relationships, for instance — lessen such pessimistic, self-blaming outlook. Such interpretation finds support in longitudinal studies, which found that overtime, PTG is a predictor of lower levels of depression (Tanyi et al., Reference Tanyi, Mirnics and Ferenczi2020). As proposed in PTG theory, growth might be best understood as an initially challenging, difficult process of self-introspection and reconstruction, from which positive psychological effects may emerge in the long run.

That is not to say that growth replaces or roots out negative psychological processes. Indeed, the non-significance of the negative association between positive and negative changes reported by our participants supports one of the key postulates in PTG theory, namely that positive and negative psychological responses to trauma are likely to coexist, and that mental “health” and “illness” evolve on two linked but distinct continua (Westerhof and Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010). This might further help to explain the lack of a clear correlation between PTG and anxiety, which is characterized by an excessive anticipation of danger, alongside anticipation of positive future events (Miloyan et al., Reference Miloyan, Pachana and Suddendorf2014; Pomerantz and Rose, Reference Pomerantz and Rose2014). Faced with the heightened threat of advanced illness, people may thus simultaneously experience deep appreciation of the present moment and strong worrying about their future.

Our results further indicate that PTG is not associated with quality of life. This is aligned with findings from young adult cancer survivors and colorectal and hepatobiliary carcinoma cancer patients, but differ from results in breast cancer patients, for whom the two dimensions are positively associated (Casellas-Grau et al., Reference Casellas-Grau, Ochoa and Ruini2017). One possible explanation for this lack of association is that at the end of life, other dimensions could “override” PTG processes in determining quality of life — such as relationships, a quality of life area where our participants scored particularly high. Overall, our findings underline the importance and uniqueness of the PTG concept in understanding the experience of those living with serious illness, capturing how they may give deeper meaning and gain greater appreciation of life in the aftermath of trauma — which is different from assessing one's own, current life as good or satisfying through a questionnaire like the MQoL-r (Tedeschi et al., Reference Tedeschi, Calhoun, Groleau and Joseph2015).

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the PTGI has been criticized for occasionally eliciting responses that reflect “defensive” growth geared towards maintaining self-esteem and control, rather than “true” growth (Zoellner and Maercker, Reference Zoellner and Maercker2006; Calhoun and Tedeschi, Reference Calhoun and Tedeschi2013). Secondly, we cannot infer causal relationships based on a cross-sectional design, which is an important limitation when investigating a transformational process like PTG. Thirdly, our relatively small sample size resulted in low statistical power and limited generalizability. As such, we were not able to explore potential associations between growth and quality of life subscales — although it would have been particularly interesting to investigate potential links between the PTG area “relating to others” and social quality of life, both of which explore aspects of participants’ relationships, such as communication, support, and compassion. Fourthly, the application of our exclusion criteria, coupled with people's refusal or inability to participate, resulted in a low participation rate — a frequent occurrence in palliative care studies. This may have induced a selection bias, with better-off patients more likely to participate than those experiencing higher levels of psychological or physical distress (White and Hardy, Reference White and Hardy2010). Finally, we did not collect data on posttraumatic stress disorder, which would have given us a more complete picture of the positive and negative responses to trauma in palliative patients. We also lack data on participants’ religious and spiritual beliefs, which would have provided context to the PTGI spiritual subscale results, and information on what people experienced as trauma and when it occurred, which could have helped to make sense of results on growth intensity and on the nature of illness-related trauma.

To gain a better understanding of the dynamic nature of PTG, future research could adopt longitudinal designs to investigate the psychological trajectories of patients overtime, in terms of both distress and growth. In addition, in order to overcome the biases inherent to the use of self-report questionnaires, future research could explore growth through patients’ autobiographical life narratives (McAdams, Reference McAdams2001; Wengraf, Reference Wengraf2001). This approach, which builds upon narratives of identity and personality development, presents an interesting new perspective for examining the cognitive and emotional processes and determinants of PTG.

Conclusion

Fifty-six percent of study participants reported moderate to very high PTG levels. We believe that this makes PTG a process worthy of further consideration and exploration in the context of palliative care. Moreover, this study uncovered a significant negative association between growth and depression. These results highlight the importance of considering PTG in the psychological care of palliative patients, which offers the possibility of “living a life at a deeper level of personal, interpersonal, and spiritual awareness” (Tedeschi et al., Reference Tedeschi, Calhoun, Groleau and Joseph2015). Interventions geared towards fostering growth, including narrative and expressive therapies (Calhoun and Tedeschi, Reference Calhoun and Tedeschi2013), may thus represent promising avenues to improve the experience of individuals in palliative care. To maximize the potential of such interventions, we must first gain a better understanding of the patterns and dynamics underlying PTG processes. A study utilizing a life narrative approach to this effect is currently in preparation.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the Leenaards Foundation for their financial support, and Prof André Berchtold, from the University of Lausanne Institute of Psychology, for his precious advice on statistical analyses. We are extremely grateful to the people who accepted to take part in this study.

Funding

This study was partly funded by the Leenaards Foundation (as part of the call for projects “Quality of life for the elderly”, grant number 3961/ss).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared none.