INTRODUCTION

It has been well documented that the rates of psychosocial distress in cancer patients at different stages of their treatment are high and that psychosocial interventions can be effective (NCCN, 2003; Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Grabsch and Clarke2007; Institute of Medicine, 2008; Watson & Kissane Reference Watson and Kissane2011; Moorey & Greer, Reference Moorey and Greer2012; Moorey, Reference Moorey2013). The prevalence of distress has been estimated to be between 25 and 47% in Western countries (Derogatis et al., Reference Derogatis, Morrow and Fetting1983; Farber et al., Reference Farber, Weinerman and Kuypers1984; Stefanek et al., Reference Stefanek, Derogatis and Shaw1987; Zabora et al., Reference Zabora, Brintzenhofe-Szoc and Curbow2001; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Angen and Cullum2004; Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Glaze and Oakland2011; Dolbeault et al., Reference Dolbeault, Boistard and Meuric2011; Gunnarsdottir et al., Reference Gunnarsdottir, Thorvaldsdottir and Fridriksdottir2012; Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Zajdlewicz and Youlden2014). Distress prevalence in Asian countries has been reported to range from 30 to 50% (Uchitomi et al., Reference Uchitomi, Mikami and Nagai2003; Akechi et al., Reference Akechi, Okuyama and Sugawara2004; Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Yamawaki and Akechi2005; Lam et al., Reference Lam, Chan and Hung2007; Shim et al., Reference Shim, Shin and Jeon2008; Wang G et al., Reference Wang, Hsu and Feng2011; Wang Y et al., Reference Wang, Zou and Jiang2013). The difference in prevalence rates may be related to the screening tools employed and the populations involved. The sample sizes in most of these studies were relatively small—between 100 and 450. There were a few exceptions. The first was the landmark study by Zabora and colleagues (Reference Zabora, Brintzenhofe-Szoc and Curbow2001), who utilized the 53-item Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) on newly diagnosed cancer patients at an oncology center in the United States with a sample size of 4,496 over a period of 6 years. The overall prevalence rate of distress for newly diagnosed cancer patients was found to be 35.1%, with a range of 29.6–43.4%. Three other studies utilizing the BSI–18 or the Distress Thermometer (DT) on more than a thousand patients reported a distress prevalence rate of 32–44% (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Angen and Cullum2004; Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Glaze and Oakland2011; Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Johansen and Annunziata2013).

Many of these studies demonstrated that gender, age, types of cancer, stage of diseases, pain, physical problems, social support, past psychiatric history, and financial stress are risk factors for psychosocial distress (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chang and Yeh2000; Zabora et al., Reference Zabora, Brintzenhofe-Szoc and Curbow2001; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Angen and Cullum2004; Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Johansen and Annunziata2013; Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Carsin and Timmons2013).

Despite strong recommendations from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and Institute of Medicine, routine screening for distress has not been offered in the majority of cancer care organizations in the U.S. (Deshields et al., Reference Deshields, Zebrack and Kennedy2013). After the distress screening, most distressed patients elected not to seek help (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Angen and Cullum2004). The levels of desire for help with distress were found to be low between 12% and 36% (Söllner et al., Reference Söllner, Maislinger and König2004; Graves et al., Reference Graves, Arnold and Love2007; Baker-Glenn et al., Reference Baker-Glenn, Park and Granger2011; Clover et al., Reference Clover, Kelly and Rogers2013; Dubruille et al., Reference Dubruille, Libert and Merckaert2015). The rates of referral acceptance by the distressed patients were found to be even lower: most of the studies reported rates between 17.8% and 28.2 % (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Akechi and Okamura2005; Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Ishibashi and Umezawa2010; Ito et al., Reference Ito, Shimizu and Ichida2011; Bauwens et al., Reference Bauwens, Baillon and Distelmans2014). However, the distress screening was found to contribute to the earlier start of psychiatric treatment (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Shimizu and Ichida2011). Routine screening for distress followed by personalized triage also resulted in more benefits for patients (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Waller and Groff2013). In order to facilitate referral acceptance, it has been recommended that patients should be asked whether they want to be referred for additional psychosocial care (Tuinman et al., Reference Tuinman, Gazendam-Donofrio and Hoekstra-Weebers2008; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Gallagher and Ryan2012; Bauwens et al., Reference Bauwens, Baillon and Distelmans2014).

The DT, with acceptable validity, has been recommended by the NCCN for screening of psychosocial distress (NCCN 2003; Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Donovan and Trask2005; Bultz et al., Reference Bultz and Carlson2006; Holland et al., Reference Holland and Bultz2011). It has been widely utilized internationally (Khatib et al., Reference Khatib, Salhi and Awad2004; Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Donovan and Trask2005; Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Yamawaki and Akechi2005; Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygur2007; Shim et al., Reference Shim, Shin and Jeon2008; Lam et al., Reference Lam, Chan and Hung2007; Holland et al., Reference Holland and Bultz2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hsu and Feng2011; Dolbeault et al., Reference Dolbeault, Boistard and Meuric2011; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Waller and Mitchell2012; Gunnarsdottir et al., Reference Gunnarsdottir, Thorvaldsdottir and Fridriksdottir2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zou and Jiang2013). At this Cancer Center (KF-SYSCC), the DT, including the Problem List (PL), has been used to screen distress for all new outpatients since 2007. When patients are identified as significantly distressed and express the desire for help from our Psychosocial Care Team (PCT), our social workers would initiate telephone or personal contact with them. When needed, patients were referred for further appropriate assessment and treatment. The PCT consists of 8 social workers, 1 clinical psychologist and 3 psychiatrists. Other resources include 2 spiritual counselors and 95 volunteers, who provide individual and/or group support.

The goal of this study was to assess, in a sizable sample, the prevalence of psychosocial distress among different cancer types and the probable related factors. We also retrospectively assessed the extent of contact established between the distressed patients and the PCT. We hypothesized that the prevalence of distress would be similar to that reported in Western countries; ethnic and cultural elements might affect the risk factors and psychosocial care patterns; and rates of contact with the psychosocial care team might be higher than reported by previous studies because of the initial outreach by our social workers.

METHODS

Data Collection

We retrieved data from the health information system at KF–SYSCC. Our cancer registry provides information about gender, age, cancer diagnosis, cancer site, cancer stage, date of cancer diagnosis, and cancer treatment received. Information on contact with the psychosocial care team (PCT)—including psychiatric consultations, outpatient visits, and psychologist visits—was obtained from registry data. There is a hospital information system at our cancer center that provides computerized physician order entry, imaging reports, laboratory and pathology reports, surgical records, and outpatient physician notes. The DT and pain scores were collected from this system.

Study Population and Eligibility

Data on all newly diagnosed cancer patients treated at KF–SYSCC between 2007 and 2010 who fit the following criteria were retrospectively collected for our study:

-

1. A cancer diagnostic category that had a sample size ≥100 in our study period (a total of 12 cancer types were selected).

-

2. Age 18 or older.

-

3. DT screening performed within 90 days of the diagnosis and before any treatment for that diagnosis.

Patients were approached by the nursing staff at the outpatient clinic to complete the Pain Scale and the DT/PL screening, along with an additional yes-and-no question: “Would you like to receive help from our psychosocial care team?” The questionnaires were collected at the outpatient clinic or sent in by mail from patients to the Department of Social Services.

Screening Tools/Questionnaires

DT screening is a self-report questionnaire that gathers information on the level of a patient's distress during the past 7 days on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 = no distress and 10 = extreme distress. It includes a Problem List, which consists of 39 questions about physical, practical, family, emotional, and spiritual/religious problems. The cutoff score for DT screening was set at ≥4, based on a previous study at our cancer center (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hsu and Feng2011). The pain score also used a 0–10 scale, with 0 = no pain and 10 = unbearable pain. According to previous studies (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Akechi and Okuyama2002; Gerbershagen et al., Reference Gerbershagen, Rothaug and Kalkman2011), a pain score ≥4 is considered moderate, which nevertheless requires intervention.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis of the demographic variables (gender, age) of the sample and the timing of screening. Rates of distress (percentage with a DT score ≥4) were summarized according to cancer type and such probable related factors as gender, age, disease stage, and pain score. In the univariate analyses, Pearson chi-square tests and an unadjusted p value were employed to demonstrate associations between prevalence rates of distress and categorical risk factors (gender, age, cancer type, cancer stage, and pain score). A stepwise logistic regression was also performed to fit the final model of distress, and adjusted p values were obtained. Information regarding patient contact with the PCT was retrieved from the computerized databases. We calculated the number of patients contacted by the PCT and plotted the timing of these contacts after DT screening. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant in all our analyses.

Ethical Considerations

The institutional review board at KF–SYSCC approved analysis of these data as a quality-improvement evaluation of clinical services and thus waived the requirement for obtaining informed consent from individual patients.

RESULTS

From the first day of 2007 to the last day of 2010, there were 5,770 newly diagnosed cancer patients seen at the outpatient clinic who had fellow-up oncology treatment at our cancer center: 8 were excluded for being younger than 18, and 427 were excluded because the number of cases for their cancer type did not reach the inclusion criteria (≥100 cases). Therefore, 5,335 newly diagnosed cancer patients representing 12 major cancer types were included in our study. Some 61.5% of our sample were women, which directly correlates with the breast cancer program, the largest program at our cancer center. Patient ages ranged from 18 to 96 years, with a mean of 53. The duration between cancer diagnosis and DT assessment ranged between 0 and 90 days (mean = 14.1 days, SD = 13.6 days). The 10th and 90th percentiles for duration were 0 and 30 days, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Gender, age, and timing of DT assessment for the prevalence sample (N = 5,335)

Overall, 1,771 (33.20%) patients were found to be significantly distressed, with a DT score ≥4. The prevalence rate varied from 22 to 36% among cancer types. Esophageal, breast, nasopharyngeal, gastric, thyroid, and lung cancers showed higher rates, while prostate and bladder cancer had the lowest. The differences were moderate (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Prevalence of distress (DT ≥ 4) and number of patients by cancer type (N = 5,335).

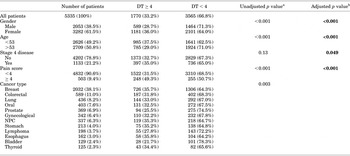

Pearson chi-square tests for associations revealed that female gender, younger age, and higher pain score were associated with higher rates of distress, while stage of disease was not. However, when the stepwise logistic regression was performed, the final model identified four variables that met the p < 0.05 significance level for entry into the model: female gender, younger age (<53 years), pain score ≥ 4, and stage 4 disease were statistically associated with distress (by adjusted p value, Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence rates of distress for five categorical risk factors (N = 5,335)

aUnadjusted p value: chi-squared test.

bAdjusted p value: logistic regression.

Among the 1,771 significantly distressed patients who were willing to receive assistance from the PCT, 628 (36%) established contact: 352 (20%) with only social workers, 206 (12%) with only psychiatrists, and 70 (4%) with both social workers and psychiatrists. As a result, of all the significantly distressed patients, 422 (24%) had contact with social workers and 276 (16%) with psychiatrists (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Contacts with the psychosocial care team by patients with DT ≥ 4.

The vast majority of these patients (up to 86%) had contact with social workers within 30 days of screening, as the social workers had made the initial effort to reach out to most of them. Visits to psychiatric staff were spread out over a year, with only 52% within the first three months (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Timing of patients' contacts with the psychosocial care team after DT screening.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of Distress and Associated Factors

Our study revealed that between 22 and 36% of newly diagnosed cancer patients are significantly distressed. As we had hypothesized, these results are similar to those reported in Western countries (Zabora et al., Reference Zabora, Brintzenhofe-Szoc and Curbow2001; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Angen and Cullum2004; Reference Carlson, Waller and Mitchell2012). There are moderate differences in prevalence rates among different cancer types. The rate of significant distress was positively associated with younger age, female gender, and higher pain score, and somewhat with stage of disease. The weak association between disease stage and rate of distress may be partially due to cultural factors and family relationships. It has been observed that a good portion of the Asian patient population may be informed only of their diagnosis and not of the stage of their illness, or their prognosis. Usually, only family members are fully apprised of a patient's condition (Tang & Lee, Reference Tang and Lee2004; Li et al., Reference Li, Yuan and Gao2012). This cultural factor associated with truthtelling practices will affect a patient's subsequent emotional response to distress.

Our univariate analysis showed that the prevalence of distress varies from one cancer type to another. However, the multivariate logistic regression conducted on type III analysis of effects based on the Wald test showed that cancer type was not statistically significant (p = 0.20). This indicates that, after controlling for gender, age, disease stage, and pain score, cancer type was not associated with a difference in prevalence of distress. The difference in DT score by cancer type seen in the univariate analysis can be accounted for by differences in gender, age, disease stage, and pain score.

Contacts with the PCT

In our study, the PCT established contact with up to 36% of distressed patients, which exceeds the higher range of most of previously reported rates of referral acceptance of 17.8–28.2% (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Akechi and Okamura2005; Reference Shimizu, Ishibashi and Umezawa2010; Ito et al., Reference Ito, Shimizu and Ichida2011; Bauwens et al., Reference Bauwens, Baillon and Distelmans2014). One exception was a study that reported an acceptance rate of 46.8% in 284 distressed patients referred to a psycho-oncology service by oncology staff (Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Rossi and Caruso2011). In that study, the staff were first trained through seminars, including webcast lectures, on the psychosocial aspects of cancer care, emotional distress, and the use of the DT/PL. This may have contributed to the much higher referral acceptance rate. However, there are reviews that discourage confidence in significant changes in clinical practice being delivered by simple educational interventions (O'Brien et al., Reference O'Brien, Rogers and Jamtvedt2007; Forsetlund et al., Reference Forsetlund, Bjorndal and Richidian2009; Bauwens et al., Reference Bauwens, Baillon and Distelmans2014).

Our results with a higher rate of contact with the PCT are partly related to the fact that our social workers proactively made phone contacts with distressed patients who had expressed a willingness to receive assistance from the team. After the initial phone call, social workers would arrange for personal or phone interviews. If necessary, patients could be referred to a psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist, or a spiritual counselor for further care. However, there was a small percentage of distressed patients who requested a meeting with social workers through referrals from the attending oncologists or due to their need for assistance with financial or other practical problems. This type of contact with social workers was estimated to be below 5% of the 24% of distressed patients who had contact with social workers.

In terms of psychiatric contacts, our finding of 16% is comparable to two previous studies conducted in Japan (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Ishibashi and Umezawa2010; Ito et al., Reference Ito, Shimizu and Ichida2011). Ito and colleagues (Reference Ito, Shimizu and Ichida2011) reported that, of 520 patients who started chemotherapy during a 6-month period, 26 (5%) were seen for psychiatric assessment and treatment. The number of patients screened positive for distress was 146 (of a total of 441 screened), yielding a distress rate of 33.1%. All patients who screened positive were recommended for a consultation with psychiatric services. Therefore, the referral acceptance rate was 17.8% (26/146). In another study, Shimizu and coworkers (Reference Shimizu, Ishibashi and Umezawa2010) reported that 25% of distressed patients received psychiatric visits. This higher rate appeared to be related to the fact that they had made every effort to schedule psychiatric appointments on the same day as the screening.

It is worth noting that contact with social workers occurred mostly within 30 days of their diagnosis, but only half of the visits to psychiatrists took place within the first 3 months. This may be due to the fact that most of patients were preoccupied with the immediate need for medical and physical management of their illness. Seeking psychiatric/psychological help can be stigmatic, or it may not be at the top of a distressed patient's priority list. Many distressed patients may prefer self-help, may fail to consider their problems serious, or are already in therapy for their distress (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang and Chiu2009; Clover et al., Reference Clover, Kelly and Rogers2013; Reference Clover, Mitchell and Britton2015). Our patients were screened weekly during all their hospital stays (for surgery or other treatments). If repeated screening showed significant distress, it could lead to further psychiatric referrals, which could be better accepted as the processes of medical treatment evolved. This may also explain why visits to the psychiatric staff were spread out in the months following their cancer diagnosis.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

One of the strengths of our study is its large sample size. The sample sizes of most previous studies on distress have ranged between 100 and 450. There were four studies that had sample sizes greater than 1,000. The first was reported by Zabora et al. (Reference Zabora, Brintzenhofe-Szoc and Curbow2001), with a sample size of 4,496. The second study used the BSI–18 on all outpatients at all treatment stages at a tertiary cancer center in Canada and had a sample size of 2,276 over a period of 4 weeks. They reported that 37.8% of their cancer patients were distressed (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Angen and Cullum2004). The third and fourth studies utilized the DT to assess cancer outpatients. The third screened outpatients during their first visit to the medical/radiation oncology clinic at a community cancer center in the United States. Of the 1,281 screenings collected over a period of 9 months, 32% rated distress above the threshold (DT ≥ 4) (Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Glaze and Oakland2011). The fourth, a multicenter nationwide study in Italy conducted during an index week at all centers, screened 1,108 newly diagnosed outpatients with cancer over a 2-day period. Some 47% of these patients fulfilled the criteria for distress when the DT cutoff was set at ≥4, and 33% when the cutoff was ≥5 (Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Johansen and Annunziata2013).

The weakness of our study is that it is retrospective in nature. The sample consisted only of patients who chose to start treatment at our cancer center, which amounted to about 60% of all new cancer outpatients. Up to 40% of the patients in our study had already received a cancer diagnosis or had been informed that they might have cancer when they first came to the clinic. Some may have gone “hospital shopping,” thus delaying initiation of treatment, as about 10% of the sample was screened more than 30 days after their diagnosis. Another weakness is that this is a single-institution study. Caution is required when generalizing our results to other oncology settings.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Our rate of contact with the PCT by distressed patients is relatively high among this type of study, but it could be even higher if it weren't for the low return rate of questionnaires, as many were not completed immediately during outpatient clinic visits. This led us to initiate a new program using electronic devices where patients could complete questionnaires on a touch screen, so that the results could be made available to the staff on a real-time basis, which will hopefully lead to prompt and appropriate delivery of psychosocial care for distressed patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Screening for psychosocial distress in newly diagnosed cancer patients at KF–SYSCC revealed that as many as a third of patients were significantly distressed, with up to 36% identified as distressed making contact with the PCT. Most patient contacts with social workers occurred within a month of screening. However, only half of the initial psychiatric visits were made within the first three months. Engaging family members while assessing patients would be a very important approach for Asian patients, because the family plays such a key role in the patient's perception of and ability to cope with their illness. A patient's follow-up contact with the psychosocial care team, especially with the psychiatric staff, should be closely monitored to facilitate timely intervention. Further studies are needed to evaluate the outcome of routine screening of psychosocial distress, of follow-up assessments, and of interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the excellent editorial assistance rendered by Jamie Chen-Fenner and Mona Wang Ono.