Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND), is a terminal, heterogeneous inherited or sporadic neurodegenerative disease characterized by the degeneration of both upper (corticospinal) and lower (spinal and bulbar) motor neurons leading to motor and extra-motor symptoms. These symptoms typically spread into different body regions with progressive muscle weakness and loss of voluntary muscle control of the bulbar, limb, thoracic, and abdominal regions, usually leading to death from respiratory failure, on average, 2–5 years after symptom onset (Hardiman et al. Reference Hardiman, Al-Chalabi and Chio2017). The severity of the illness and uncertainties regarding the time course of disability demands clinical care centered around the patient and carers. Disease-focused expertise offer a multidisciplinary approach that leverages the experience of several health-care providers in order to control the symptoms and assist people with ALS (PALS) to reach their fullest potential, assist their routines and participation, and maximize physical, psychological, and emotional comfort during disease progression (Gonçalves and Magalhães Reference Gonçalves and Magalhães2022; Hogden et al. Reference Hogden, Foley and Henderson2017; Paganoni et al. Reference Paganoni, Karam and Joyce2015). When faced with a terminal illness like ALS/MND, there is a tendency to question the meaning of life and death (Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Cotton and He2021).

Spirituality is a domain of supportive and palliative care in some national policies, and the European Association for Palliative Care has published a white paper encouraging multidisciplinary education on spiritual care for palliative care staff in order to provide this support as an integral part of palliative care (Best et al. Reference Best, Leget and Goodhead2020). PALS and their caregivers may seek out spirituality as a way to cope with disease progression, minimize their suffering, or provide hope. In this context, spirituality and religiosity must be distinguished as these terms are typically used as synonyms. Spirituality refers to personal attempts to understand final questions about life and their relation to the sacred and transcendent, including enhancement of meaning and purpose of life, relationship maintenance, provision of comfort, hope, and coping strategies, and a satisfying moral connection beyond the self and its relationship with others and a higher power (Evangelista et al. Reference Evangelista, Lopes and Costa2016; O’Brien and Preston Reference O’Brien and Preston2015; Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, Smith and Paasche-Orlow2020; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Cotton and He2021). Religion, in turn, corresponds to an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols aimed at facilitating closeness between individuals and the sacred, with religiosity being the ground level of religion, with which individuals believe, follow, and practice a given religion (Delgado-Guay Reference Delgado-Guay2014; Evangelista et al. Reference Evangelista, Lopes and Costa2016). Spirituality can lead, or not, to the development of religious practices (Selman et al. Reference Selman, Brighton and Sinclair2018; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Cotton and He2021).

Despite the significance and prevalence of spiritual distress and needs in the context of advanced disease, these needs were often reported as neglected, and spiritual care was lacking in patients facing terminal illness and their caregivers.

Few studies evaluate the role of spirituality and the role of spiritually integrated interventions targeting PALS and their caregivers. Therefore, the value of understanding the nexus of PALS and their caregivers and spirituality is undermined. In order to address this gap, we conducted a scoping review to synthesize research on the intersection of these topics to answer the question: what has been published in peer-reviewed literature about the role of spirituality, interventions targeting programs to address spiritual needs, and their outcomes for PALS and their caregivers?

Methods

A scoping review of scientific literature was performed with the primary objective of mapping scientific knowledge, based on the guidelines of the Joanna Briggs Institute for this type of study (Peters et al. Reference Peters, Marnie and Tricco2020). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff2009) was used to organize the information, and the recommendations described in PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews were followed (Tricco et al. Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin2018).

Research method

To answer our research question, we selected the scoping review methodology. Peer-reviewed articles published until April 2022 were obtained from CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE Complete, MedicLatina, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and SPORTDiscus. To identify relevant articles, search terms were focused on 2 distinct areas. First, keywords relating to “ALS” and “Motor Neuron Disease” were identified to capture the disease in question. Second, terms focusing on the relevant areas of “Spirituality” were identified for the current study. Combinations of descriptors were used, including medical subject headings, subject headings, and subject terms for each database, as well as using free-text terms and the “*” tool, which enhanced the search by including variations of the same word ((“amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”) OR (ALS) OR (“motor neuron disease*”) OR (ALS/MND) OR (“Motor Neuron Disorder*”) OR (MND)) AND ((Spirituality) OR (Spiritualism) OR (“spiritual need*”) OR (“spiritual care”) OR (“spiritual issue*”) OR (Existentialism) OR (“Life Purpose”) OR (“meaning*”) OR (“spiritual value*”)).

Inclusion criteria

To be included in this review, an article had to address spirituality in patients with ALS/MND and in their caregivers, namely, in the domain of meaning/purpose of life, throughout the disease course. The search methodology included all types of qualitative, quantitative, and mix-method studies, regardless of their design. Only articles written in English, Spanish, French, and/or Portuguese were selected from articles worldwide.

Exclusion criteria

Publications that did not target PALS or their caregivers’ outcomes were excluded, such as health-care professionals providing services to the patients and families. In addition, publications were excluded if they only addressed religiosity or whose focus was not spirituality. Finally, publications that fulfilled the aforementioned criteria but reported studies other than primary research were also excluded, such as editorials, letters, concept papers, review articles, unpublished (gray) literature, dissertations, books, and book studies.

Selection and eligibility of articles

The results of each search in the different databases were imported into the bibliographic reference management software Mendeley®. Duplicate references were removed, and an initial selection by title and abstract was independently conducted by 2 researchers (F.G. and M.I.T.) using Rayyan® according to the outlined inclusion/exclusion criteria.

The full texts of the remaining references were obtained to determine their inclusion or exclusion in the final study based on the full text. Disagreements on the inclusion of an article were subject to discussion with a third researcher (B.M.) to reach a consensus. The PRISMA model was used to organize the information resulting from the article selection process.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were obtained using customized extraction forms. The following information was recorded for each study: (a) study ID, (b) author and year of publication, (c) country, (d) aim, and (e) population and characteristics. Two researchers performed the data extraction and synthesis processes independently (F.G. and M.I.T.). A third researcher (B.M) resolved any disagreement. Finally, the data were sorted into tables through a narrative summary of the data extracted from each article.

Thus, the data related to spirituality identified in the studies with a qualitative component were recorded according to (a) author and year, (b) category, (c) subcategory, (d) descriptive theme, and (e) population. In studies with a quantitative component, the data were recorded according to (a) author and year, (b) measures and type of intervention, (c) findings, and (d) population. Two double-entry tables were constructed based on the dimensions evaluated for each study. Numerical referencing was used to identify the studies.

To map the knowledge obtained from the analysis of the themes and subthemes that emerged from the studies, a thematic construction and analytical structure was carried out, with the respective schematic and numerical representation of the included studies.

Results

Selection of studies

A total of 1,208 articles were extracted from the initial search carried out in the different databases. After removing the duplicates, 1,136 articles were selected for the first analysis by title and abstract. The full-text analysis included 55 articles, of which 18 were considered for this review (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Process of identification and inclusion of studies – PRISMA diagram flow.

Characterization of the studies

Table 1 presents the summary information of the final studies analyzed, including authors, year, country, study aim, type of study, and population and characteristics. Most of the identified studies were qualitative (n = 14) (Akiyama et al. Reference Akiyama, Kayama and Takamura2006; Cipolletta and Amicucci Reference Cipolletta and Amicucci2015; Dos Santos Costa et al. Reference Dos Santos Costa, Comassetto and Maria Dos Santos2021; Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Foley et al. Reference Foley, O’Mahony and Hardiman2007; Hamama-Raz et al. Reference Hamama-Raz, Norden and Buchbinder2021; Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Jeppesen and Handberg2018; O’Brien and Preston Reference O’Brien and Preston2015; Ozanne et al. Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2013, Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2015; Rosengren et al. Reference Rosengren, Gustafsson and Jarnevi2015; Warrier et al. Reference Warrier, Sadasivan and Polavarapu2020; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Peng and Zeng2021) and used semi-structured interviews for data collection except 2 studies: one used biographies selected through a search by keyword (Rosengren et al. Reference Rosengren, Gustafsson and Jarnevi2015) and the other used internet and print-published narratives written by people with ALS/MND (O’Brien and Preston Reference O’Brien and Preston2015). Three were identified as quantitative (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, O’Connor and Kane2014; Fegg et al. Reference Fegg, Kögler and Brandstätter2010; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Felgoise and Walsh2009): 1 was a cross-sectional study that utilized a single treatment group (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, O’Connor and Kane2014) and the other 2 were cross-sectional studies with the application of scales (Fegg et al. Reference Fegg, Kögler and Brandstätter2010; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Felgoise and Walsh2009). The protocol (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, Aoun and O’Connor2012) was the basis for a study (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, O’Connor and Kane2014).

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies

Note: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; MND, motor neuron disease; QoL, quality of life.

Characterization of the participants

The characteristics of the participants in the selected studies are summarized in Table 1. A total of 378 patients participated in the studies, 214 ALS patients and 164 caregivers. In one study, the sample was not the primary caregiver but all family members in contact with the patient and somehow care for them (Cipolletta and Amicucci Reference Cipolletta and Amicucci2015).

Three studies used a sample with ALS patients and caregivers (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, Aoun and O’Connor2012; Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Jeppesen and Handberg2018). One of them was the protocol that recruited a total of 100 participants, of which half were ALS patients and the other half caregivers (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, Aoun and O’Connor2012).

From 10 studies that included ALS patients, 4 did not indicate the sex of the patients (Foley et al. Reference Foley, O’Mahony and Hardiman2007; Hamama-Raz et al. Reference Hamama-Raz, Norden and Buchbinder2021; Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009; O’Brien and Preston Reference O’Brien and Preston2015), 4 did not indicate the mean age (Foley et al. Reference Foley, O’Mahony and Hardiman2007; Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009; O’Brien and Preston Reference O’Brien and Preston2015; Rosengren et al. Reference Rosengren, Gustafsson and Jarnevi2015), and 3 did not indicate the time since diagnosis (Fegg et al. Reference Fegg, Kögler and Brandstätter2010; Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009; Rosengren et al. Reference Rosengren, Gustafsson and Jarnevi2015).

From the 8 studies that included caregivers, 6 presented spouses as being the most prevalent family related in the care of patients with ALS. Only 1 study showed incomplete information about the mean age, gender, and relationship with the patient (Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009).

Characteristics of studies with a qualitative component

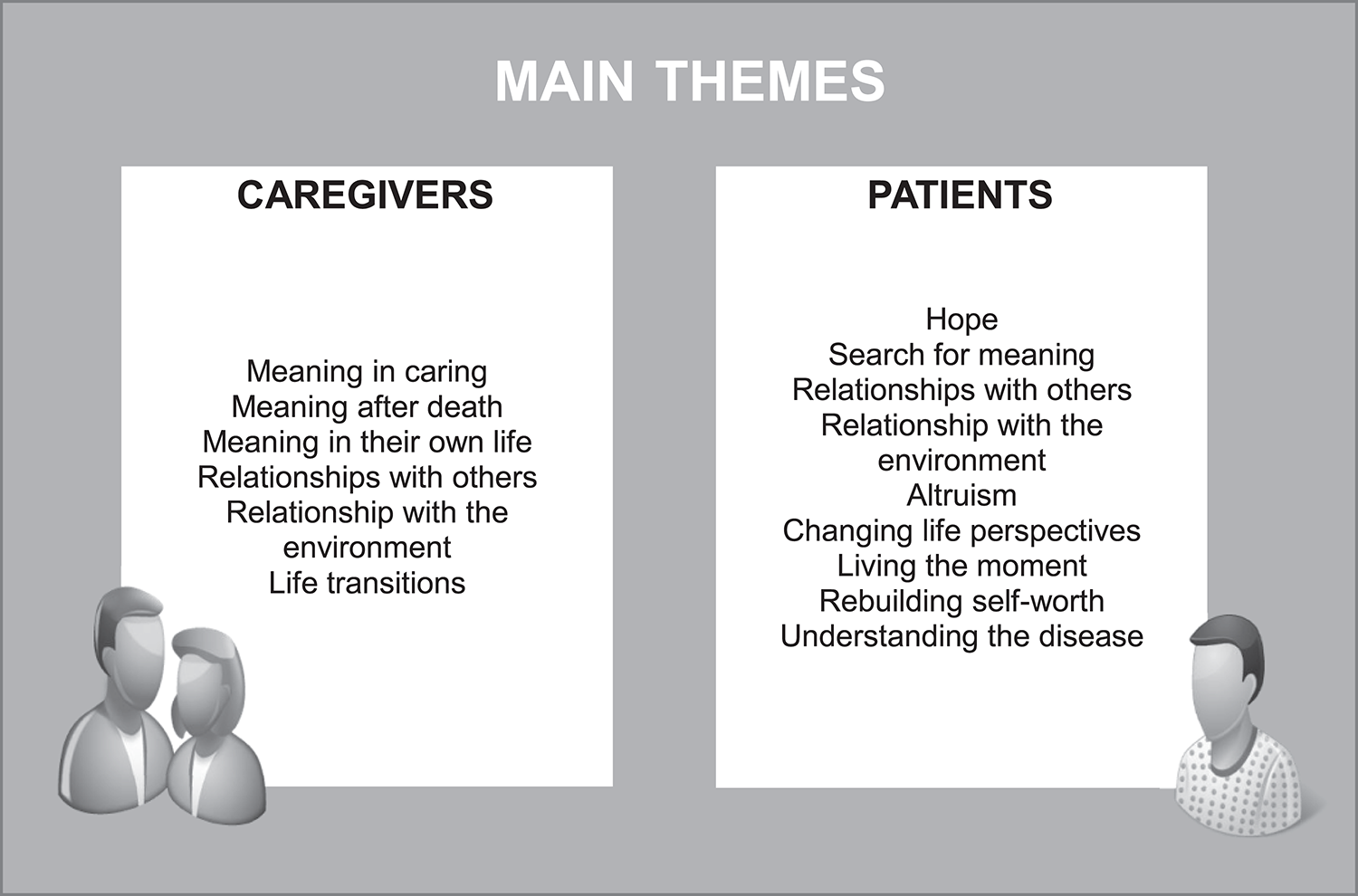

Table 2 describes the resulting categories and subcategories of the studies. The main themes for caregivers and patients are represented in Figure 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of studies with a qualitative component

Fig. 2. Main themes for caregivers and patients, based on the qualitative studies.

Caregivers

Caregivers highlighted the meaning in caring by continuous processing of knowledge and the understanding of ALS, where caregivers intensified experiences living a shared meaningful everyday life among PALS (Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Jeppesen and Handberg2018). For the family caregiver, the process of care was more than an act and assumed a sense, driven by love and a mutual exchange understood in the valorization of being, giving meaning to the life of both (Dos Santos Costa et al. Reference Dos Santos Costa, Comassetto and Maria Dos Santos2021).

Caregivers reported changes in the marital relationship, intimacy, and communication between the couple, and in addition, they did not have time for themselves since caregiving became their primary focus and major responsibility (Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009; Warrier et al. Reference Warrier, Sadasivan and Polavarapu2020). However, they reported that relationships with others and the environment were illuminated as meaningful for their own life and must be preserved (Ozanne et al. Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2015).

Spirituality involved the imminence of the loss process, as well as the need to adapt to a new reality in life, which included the addition of limitations of basic functions that fleetingly impact the routine and habits (Dos Santos Costa et al. Reference Dos Santos Costa, Comassetto and Maria Dos Santos2021). The course of the disease alters normative life transitions of the caregivers, namely, with the increasing need for care, for example, when mechanical ventilation is requested to prolong the life of an ALS patient (Akiyama et al. Reference Akiyama, Kayama and Takamura2006). A feeling of being supported by health-care professionals, self-help groups, and other people influenced finding meaning in prolonging life (Akiyama et al. Reference Akiyama, Kayama and Takamura2006; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Jeppesen and Handberg2018; Ozanne et al. Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2015).

Even in the end stage, when patients cannot react, caregivers reported that they find other meaning in the situation to continue caring for them (Akiyama et al. Reference Akiyama, Kayama and Takamura2006). Shortly after the partner’s death, a shift is highlighted in the wishes for their own life to change, and thoughts of a continued life arose (Ozanne et al. Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2015).

Patients

Patients expressed 2 different ways of living with the disease: either to lie down, be angry, and let the disease take over the everyday life or to live right here and now, the time that is left. In Rosengren et al.’s (Reference Rosengren, Gustafsson and Jarnevi2015) study, female patients highlighted that they took control of their life situation by choosing to live in the moment. While trying to make sense of life, some patients search for a positive aspect to emerge as a tranquil composure and hope, acquiring strength from turning misfortune into an advantage (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, O’Connor and Kane2014; Hamama-Raz et al. Reference Hamama-Raz, Norden and Buchbinder2021). They argue that the feeling gets stronger to utilize all moments regarding a limited lifetime where every second counts (Rosengren et al. Reference Rosengren, Gustafsson and Jarnevi2015).

Several participants stated that their perspectives had changed. Appreciation of the new life was interpreted differently by patients: some, instead of enjoying participating in activities with their loved ones, were now able to enjoy watching them (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008). Other perspectives included gratitude for past experiences, appreciation of residual time and function, living in the present, appreciation of the natural world, and the importance of getting things done (Foley et al. Reference Foley, O’Mahony and Hardiman2007; Ozanne et al. Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2013). Others hoped that the disease would stop or at least not become much worse and survive over a particular time (Hamama-Raz et al. Reference Hamama-Raz, Norden and Buchbinder2021; Ozanne et al. Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2013; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Peng and Zeng2021). Many kept their mind occupied by focusing on daily activities or hobbies like continuing to work while still able to do. However, some chose to stop work to concentrate on other more valued aspects of their lives, make holiday trips as a distraction, as an assertion that life was not yet over and was there to be enjoyed, writing to reflect on their lives, and meditation to help in their search for giving meaning to their situation (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Peng and Zeng2021).

Computer technology accessibility and augmentation played an increasingly important part in this new way of life by providing opportunities for virtual socializing through online forums, access to information to enable people to manage their own condition, and, crucially, voice software for augmentative and alternative communication to restore a voice to those unable to speak (Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009).

A sense of community that supported the internal relationships between PALS and their relatives occurred, building up a sense of fighting ALS together (Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Jeppesen and Handberg2018; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Peng and Zeng2021). This sense of community was reported as meaningful in different studies, where the process of sharing the experience of living with ALS among patients and caregivers was very important and self-described by patients as “openness, understanding, joy of life, and humor.” Sharing laughs can also be important and helps to disarm the tragedy of the disease; a good sense of humor and calm with caregivers and health-care professionals helped to deal with problems when something went wrong and feel being accepted as an individual (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Ozanne et al. Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2013; Rosengren et al. Reference Rosengren, Gustafsson and Jarnevi2015).

Characteristics of studies with a quantitative component

Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, Aoun and O’Connor2012 (S7) created a study protocol with the potential to provide a precise intervention based on Dignity therapy to ameliorate psychosocial and existential distress and improve the quality of care provided to people with ALS and their family caregivers. The cross-sectional study S9 (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, O’Connor and Kane2014), developed by the same author in 2014, showed that the individual results on anxiety and depression are encouraging and suggest that dignity therapy has the potential to decrease anxiety and depression in family caregivers who are experiencing moderate to high levels of distress. Family caregivers felt that the therapy provided a benefit to their family members and that the document would help them in bereavement, describing the experience as satisfactory and recommending it to others. Whether a family caregiver was directly involved in the therapy or not had little impact on the acceptability or feasibility of the intervention. However, family caregivers’ level of acceptance of their partner’s imminent death, or the quality of the relationship between family caregiver and partner, may be negatively impacted, as suggested by the comments that were provided on the feedback questionnaire, which can lead to dignity therapy having a potentially negative impact on family caregivers at the time of the intervention.

Murphy et al. (Reference Murphy, Felgoise and Walsh2009) used different scales to study the relationship between several variables in caregivers; for example, the relationship between spirituality, measured by the Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS), with quality of life (QoL), measured by the Quality of Life Inventory, Overall Life Satisfaction Score (QoLI), and psychological morbidity, measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory, General Severity Index Score (BSI). Spirituality was considered a significant predictor of QoL (0.321; p < 0.01) but not a significant predictor of psychological morbidity.

Fegg et al. (Reference Fegg, Kögler and Brandstätter2010) used the Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation Scale (SMiLE), a measure to assess the meaning in life (MiL), in PALS comparing with a representative sample of the German population. Subjects of the representative sample showed a significantly higher SMiLE index (indicating the overall importance of the respondent’s MiL areas) compared to PALS (p < 0.001). This was due to a significantly higher satisfaction in the listed MiL areas (p < 0.001). However, importance ratings between importance and satisfaction did not differ significantly.

The results of the studies are described in Table 3.

Table 3. Studies with a quantitative component

Note: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; QoL, quality of life; MiL, meaning in life; SMiLE, Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation Scale.

Discussion

This scoping review broadly examined the nature and extent of research on the relevance of spirituality and the role of spiritually integrated interventions targeting PALS and their caregivers. Most literature is based on qualitative approaches. These are useful to identify experiences and self-related perceptions, especially in the light of spirituality, a domain where open questions and narratives can be a useful method to understand and narrow the path of the interventional approaches (Fanos et al. Reference Fanos, Gelinas and Foster2008; Foley et al. Reference Foley, O’Mahony and Hardiman2007; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Jeppesen and Handberg2018; O’Brien and Preston Reference O’Brien and Preston2015; Ozanne et al. Reference Ozanne, Graneheim and Strang2015; Rosengren et al. Reference Rosengren, Gustafsson and Jarnevi2015). Furthermore, qualitative studies highlight the importance of differential approaches according to the stage of the disease and its progression (Akiyama et al. Reference Akiyama, Kayama and Takamura2006; Dos Santos Costa et al. Reference Dos Santos Costa, Comassetto and Maria Dos Santos2021), including the availability to speak and communicate and to use augmentative and alternative strategies that allow PALS to express their insights during the course of the disease and to actively communicate with their family and caregivers (Locock et al. Reference Locock, Ziebland and Dumelow2009).

The quantitative instruments adopted by studies on the spiritual dimension is relevant, and the research summarized by the present scoping review considers only a small number of them: SPS and SMiLE (Fegg et al. Reference Fegg, Kögler and Brandstätter2010; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Felgoise and Walsh2009). Nonetheless, others can be found in the literature and can be used in further studies to evaluate and to monitor PALS and caregivers’ progression (Blaber et al. Reference Blaber, Jones and Willis2015), with some common instruments that can be used in a palliative care setting to measure QoL, in general, and spiritual well-being, in particular, as well as different domains of spirituality (relation with themselves, other people, environment, or transcendental). When selecting the appropriate instrument in PALS, researchers and health-care providers should consider the clinical and cultural traits of the population, as well as the validation of their psychometric properties (Long Reference Long2011). This study highlights the importance of integrative care that goes beyond the biologic aspects of interventions and that considers the spiritual needs. Therefore, it can encourage professionals to consider this dimension when delivering care to PALS and caregivers and consider this dimension a useful and indispensable component of palliative care (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Shin and Choi2012). Accordingly, this increases the need for increased investment in health-care professionals’ education, training, and capacitation for times when healing therapies can no longer control the disease and spiritual support can help manage distress, meaningfulness, and QoL (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Shin and Choi2012; Long Reference Long2011). The importance of spiritual care is highlighted, especially in a situation like ALS that affects a person’s sense of meaning in life due to its impacts on physical activity, social participation, self-perception deterioration, and loss of autonomy. The evidence included in this review suggests the need to address the loss of hope or meaning in life for PALS and their caregivers during the course of the disease and after the bereavement and continuous life transitions. Furthermore, this includes strategies targeting the rebuilding of the self-worth, changing life perspectives, and continuous capacitation and promotion of the ability to establish efficient relationships with others and the environment.

This scoping review indicates several directions for future investigation, especially systematically including spirituality in palliative care teams and interventions aimed at PALS and their caregivers.

Some limitations of the present study include the exclusion of studies in languages other than English, Spanish, Portuguese, or French. Second, as it was a scoping review, we did not systematically assess the scientific rigor of our literature sample.

It is also important to highlight an additional limitation resulting from the current state of the literature based on the nature and categorization of spirituality. The unclear delimitation of the boundary and definition of spirituality is also a finding in and of itself. Nevertheless, defining thematic subcategories in spirituality as we did in this scoping review can be a useful tool to guide health-care providers to better structure their intervention and assessment of the spirituality domains and their evolution along different stages of the disease or even after with regards to caregivers’ self-identification and rebuilding their paths after bereavement.

More intervention should be empirically developed in order to test spirituality and spirituality care on the impact over QoL, copping, and readjustment to life at the different stages of PALS and their caregivers. In addition, there is a clear need to raise awareness of this among health-care professionals involved in providing this care.

Conclusion

This scoping review illustrates the importance given to spirituality by caregivers and PALS with respect to 2 principal domains: (1) searching for meaning and purpose of life; (2) the relationships between them, others, and the environment. Overall, this review found support for spiritual-integrated care interventions for PALS and their caregivers. Spirituality is considered to be a unique part of everyday interactions and life, and spiritual care should always be considered as a way to target and improve patients’ and their caregivers’ QoL by addressing psychosocial and spiritual suffering and capacitation that can make the difference throughout the whole disease course, and the constant search for meaning was, in the most of times, the strength to continue the journey on its different domains.

Therefore, practitioners in contact with PALS and their caregivers must have proper training, formation, and capacity to assess and address the spiritual needs and to explore and put in practice ways of intervening and evaluating their applicability, being able to recognize the signs of distress experienced and prove an effective continuous follow-up and way to communicate with PALS.

Thus, it is of great importance to carry out experimental studies in the area of spirituality in order to systematically explore the impact of spiritual interventions and their results.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.