Introduction

The lived experience of cancer can impact all aspects of patients’ lives, influencing patients’ personal perceptions and affecting their sense of control. Perceived control, “the belief that one can determine one's own internal status and behavior, influence one's environment, and/or bring about desired outcomes” (Wallston et al., Reference Wallston, Wallston and Smith1987), can play an important role in patients achieving their care goals and in predicting physical (Infurna et al., Reference Infurna, Ram and Gerstorf2013) and psychosocial outcomes (Bárez et al., Reference Bárez, Blasco and Fernandez-Castro2007; Ranchor et al., Reference Ranchor, Wardle and Steptoe2010; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Lent and Raque-Bogdan2012). Perceptions of control have been shown to be modifiable and can be enhanced (Thompson, Reference Thompson, Snyder, Lopez, Edwards and Marques2021), thus creating pathways for patient empowerment and improved outcomes (Bailo et al., Reference Bailo, Guiddi and Vergani2019). Given the potential adaptive value of personal control in cancer, the Cancer Support Community (CSC) advocacy organization developed Valued Outcomes in the Cancer Experience (VOICE)™, a measure of patients’ perceived control over personal priorities within their cancer experience.

Although not all aspects of cancer can be controlled at all timepoints in the cancer continuum, enhancing patients' sense of control may positively impact their psychological well-being, hope, and resilience (Chi, Reference Chi2007; Bárez et al., Reference Bárez, Blasco and Fernández-Castro2009; Gorman, Reference Gorman, Bush and Gorman2018; Seiler & Jenewein, Reference Seiler and Jenewein2019). In CSC's Patient Empowerment Theoretical Framework, the enhancement of patient control is hypothesized to play a key role in changing patients’ beliefs about cancer and promoting positive behavior change, thus leading to improved patient well-being (Golant et al., Reference Golant, Zaleta, Ash-Lee, Breitbart, Butow, Jacobsen, Lam, Lazenby and Loscalzo2021). Prospective research shows that perceived control can change across the course of cancer (Bárez et al., Reference Bárez, Blasco and Fernández-Castro2009) and that patients who reported a greater sense of control after diagnosis also experience lower levels of psychological distress at 6- and 12-months post-diagnosis (Ranchor et al., Reference Ranchor, Wardle and Steptoe2010). Further, evidence suggests that even when accounting for effects of physical factors such as symptom burden and patient functional status, patients’ perceptions of control over their disease experience are independently predictive of depressive and anxiety symptoms (Zaleta et al., Reference Zaleta, Miller and Olson2020). Perceived control has also been shown to mediate the relationship between patients’ utilization of complementary and supportive therapies and their emotional well-being (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Miller and Arora2012). Collectively, these findings underscore the important role of patients’ perceptions of control for their well-being.

A measure that captures patients' sense of control in the face of a complex and diverse cancer care landscape has the potential to guide understanding of the patient experience and aid the development of supportive care interventions to enhance well-being. Traditional measures of perceived control in the context of illness have focused globally on patients’ sense of mastery of life problems and overall locus of control (Pearlin & Schooler, Reference Pearlin and Schooler1978; Wallston et al., Reference Wallston, Wallston and DeVellis1978) or narrowly on patients’ views about the controllability of disease course and perceived strain of the disease (Moss-Morris et al., Reference Moss-Morris, Weinman and Petrie2002; Hou, Reference Hou2010). Patients facing health threats routinely balance multiple priorities beyond delaying disease progression. These priorities can be broadly related to life plans (e.g., being present for important family events, having a sense of purpose in life), or more directly connected to the illness experience itself (accessing affordable care, engaging in shared decision-making, and minimizing pain and discomfort) (Jim et al., Reference Jim, Purnell and Richardson2006; Ellis & Varner, Reference Ellis and Varner2018; Rapkin et al., Reference Rapkin, Garcia and Michael2018; Covvey et al., Reference Covvey, Kamal and Gorse2019). Consequently, an important opportunity exists to develop a flexible and multifaceted measure of cancer patients’ personal sense of control over diverse areas of the cancer experience.

In the present study, we developed VOICE, a measure of patient perspectives about their personal control over goals that are highly valued and relevant to cancer patients. The specific aims of the study were to (1) construct and refine the VOICE measure and (2) evaluate the psychometric properties of the final VOICE scale.

Methods and results

Scale development and validation were completed in three phases, each with separate participant samples: (I) item generation and initial item pool testing, (II) scale refinement, and (III) confirmatory validation analysis to corroborate scale psychometric properties and dimensionality. Participants were recruited through CSC's Cancer Experience Registry (an online, community-based research initiative examining the emotional, physical, practical, and financial impact of cancer), and through referrals from CSC's U.S.-based network partners, including Cancer Support Community and Gilda's Club partners. Phases II and III also included expanded recruitment efforts through CSC's MyLifeLine online community, social media, and advocacy partnerships. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional research policies and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Phase I: Item generation and initial item pool testing

Item generation

Initial item development was informed by exploratory qualitative focus groups and interviews with cancer patients (n = 8) and caregivers (n = 6) conducted between October and December 2016. Patient diagnoses included chronic myeloid leukemia (n = 5) and metastatic breast cancer (n = 3); caregivers provided care to patients living with lung, renal, and breast cancers, and multiple myeloma. Patients and caregivers were recruited separately. To understand and identify valued outcomes important to the cancer experience, discussions explored participants’ views on hope and well-being. Two key findings emerged: first, participants operationalized the concept of hope in terms of what they hoped for, describing a diverse range of personal priorities. Second, participants described having a sense of control in achieving their priorities as fundamental to psychosocial well-being. These findings, along with the input of a project advisory committee comprised of individuals with oncologic expertise in psychology, behavioral science, nursing, social work, and population health, were used to inform the development of response scale anchors and to generate an item pool of 54 valued priorities, representing 13 conceptual domains: Emotional Coping, Financial Capability, Functional Capacity, Health Engagement, Illness Knowledge, Longevity, Maintaining Independence, Personal Identity, Planning for the Future, Quality Care, Social Support, Spirituality, and Symptom Management. All items were worded in the positive direction to reduce the potential cognitive burden for respondents (Suárez-Alvarez et al., Reference Suárez-Alvarez, Pedrosa and Lozano2018), given the risk for cognitive impacts among cancer patients and survivors (Pendergrass et al., Reference Pendergrass, Targum and Harrison2018). Each item was paired with two rating scales: first, participants were asked to rate their sense of personal control using a 5-point scale (“Today, how much can you control whether … ”; 0 = Not at all; 1 = A little bit; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = Quite a bit; 4 = Very much). Each item was additionally rated by participants for level of personal importance on a 5-point scale (“Today, how important to you is … ”; 0 = Not at all; 1 = A little bit; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = Quite a bit; 4 = Very much) to guide prioritization of scale items. The 5-point Likert-type response format and anchors were selected in alignment with scale construction recommendations for unipolar items in health, social, and behavioral research (Krosnick & Presser, Reference Krosnick, Presser, Wright and Marsden2009; Boateng et al., Reference Boateng, Neilands and Frongillo2018) and have been widely used in measuring patients’ self-appraisals of their experiences (e.g., Chang et al., Reference Chang, Hwang and Feuerman2000; Webster et al., Reference Webster, Cella and Yost2003). To assess item clarity, relevance, and interpretation, cognitive interviews were conducted with cancer patients (n = 7; 42% of whom reported high school/GED equivalence or associate degree); item phrasing was adjusted in response to feedback.

Initial item pool testing

To identify domains and corresponding items of the highest importance to cancer patients and to reduce the initial item pool, items were tested through an online survey of 459 cancer patients recruited between November 2017 and April 2018, as previously described (Zaleta et al., Reference Zaleta, McManus and Buzaglo2019). Participants rated each item for personal control and importance, as described above, and also completed a series of cross-validation measures. Item descriptive statistics and iterative exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of importance ratings were executed to reduce the item pool according to patients’ prioritization of items. Items that had low importance ratings, did not load in the EFA at a level of ≥0.30, or were not related to conceptually relevant validation measures were reworded or removed to eliminate redundancy. In sum, 24 items were retained, 9 items were reworded, 21 items were removed, and 2 items were added to ensure conceptual domains were adequately represented. To reevaluate item clarity and comprehension, additional cognitive interviews were conducted with cancer patients (n = 8, 50% of whom reported high school or some college education) to confirm phrasing and comprehension. The interim VOICE measure comprised 35 items representing 14 conceptual domains: Access to Care, Care Coordination, End-of-Life Preparedness, Financial Capability, Functional Capacity, Health Engagement, Illness Knowledge, Longevity, Maintaining Independence, Personal Identity, Shared Decision-Making, Social Support, Spirituality, and Symptom Management.

Phase II: Scale refinement

Participants

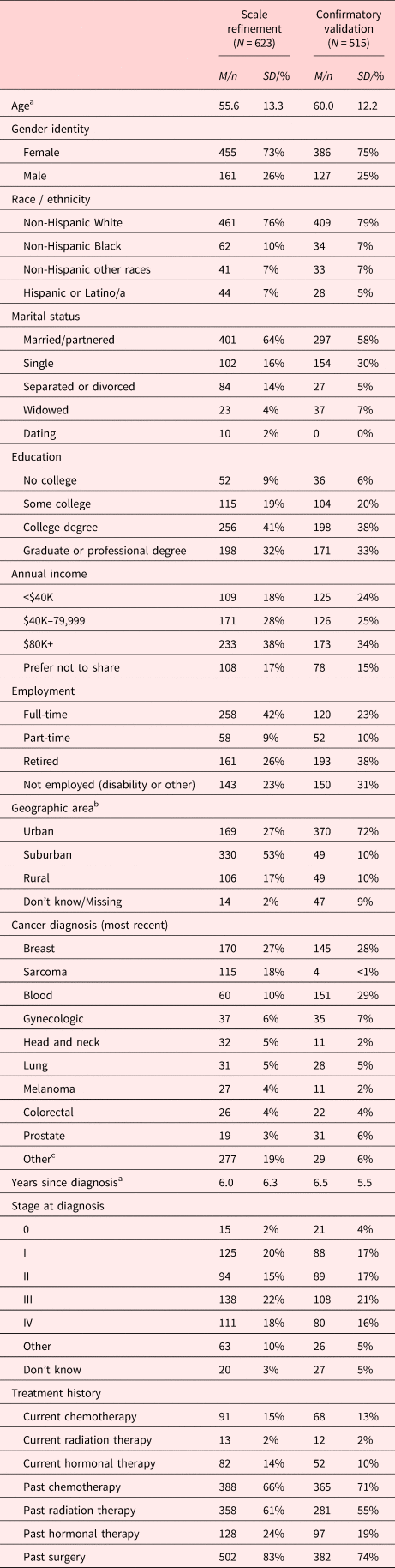

Participants for VOICE scale refinement efforts were recruited between May 2019 and February 2020. Individuals aged 18+ years who had ever received a cancer diagnosis and who could read English were eligible to participate; the sample comprised 623 participants who completed all VOICE items (Table 1). Participants provided informed consent online prior to survey completion, which took approximately 40 min. Ethics approval was obtained from Ethical and Independent Review Services (E&I, Independence, MO; Study # 16095).

Table 1. Participant descriptive characteristics

a Subsample sizes for Scale refinement sample: Age (n = 614), Years since diagnosis (n = 607); Confirmatory validation sample: Age (n = 515), Years since diagnosis (n = 515). Aside from Age and Years since diagnosis, the reported proportions above are calculated out of Scale refinement and Confirmatory validation total Ns (N = 623 and N = 515, respectively). Percentages may not total 100% due to incomplete or missing data.

b Geographic area self-reported in Scale refinement sample and derived from participant-reported zip codes in Confirmatory validation sample.

c Other cancers (≤1% each) included: esophageal, non-melanoma skin, thyroid, pancreatic, kidney, brain, and bladder, among others.

Measures

-

Socio-Demographics and Clinical History. Socio-demographic and clinical information (age, gender identity, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, annual household income, geographic area, self-reported cancer diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and cancer treatments received) were collected from participants.

-

VOICE. The 35 draft VOICE items were rated on two scales, level of perceived control (“Today, how much can you control whether … ”), and perceived importance (“Today, how important to you is … ”). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = Not at all; 1 = A little bit; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = Quite a bit; 4 = Very much).

-

PROMIS-29. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-29 (PROMIS-29 v2.0; Cella et al., Reference Cella, Riley and Stone2010) was used to assess self-reported symptoms and functioning across seven domains: depression, anxiety, pain interference, fatigue, sleep disturbance, physical functioning, and ability to participate in social roles and activities. Each domain is comprised of four items, rated on a 5-point scale, with an additional item on pain intensity rated from 0 to 10 (“no pain” to “worst pain imaginable”). Scale scores were converted to standardized T-scores (Mean = 50, SD = 10); normative reference groups are the U.S. general population, except sleep disturbance, where comparisons are to a mix of the U.S. population and people with chronic illness.

-

HHI. The Herth Hope Index (HHI; Herth, Reference Herth1992) was used to measure hope in the participant sample. The HHI is a 12-item measure developed to measure hope in adults in clinical settings. Items are rated on a 4-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 4 = Strongly agree).

-

FACIT-COST. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACIT) COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST, Version 1; deSouza et al., Reference deSouza, Yap and Wroblewski2017) was used to assess financial toxicity. The 11-item measure assesses financial distress in cancer patients, with participants rating each item in reference to the past seven days on a 5-point scale (0 = Not at all; 4 = Very much).

-

GSE-SF. The General Self-Efficacy — Short Form (Romppel et al., Reference Romppel, Herrmann-Lingen and Wachter2013) measure was used to assess general self-efficacy. The 6-item scale asks participants to rate each item (e.g., “It is easy for me to stick to my aims and accomplish my goals”) on a 5-point scale (1 = Not true at all; 4 = Exactly true).

-

C-CARES Care Coordination. The Care Coordination subscale from the Cancer Care Assessment and Responsive Evaluation Studies (C-CARES; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Zullig and Phelan2015) survey was used to evaluate patient experiences with medical care coordination. The 4-item subscale rated participant experiences on a 5-point scale (1 = Never; 4 = Always).

-

PSQ Accessibility and Convenience. The Accessibility and Convenience subscale from the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18; Marshall & Hays, Reference Marshall and Hays1994) was used to measure medical care experience. The 4-item subscale measures experiences of receiving medical care on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly agree; 5 = Strongly disagree).

-

PTGI-X. The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory — Expanded (PTGI-X; Tedeschi et al., Reference Tedeschi, Cann and Taku2017) examines patient perspectives following a cancer diagnosis across five domains: Appreciation of Life (3 items), Personal Strength (4 items), New Possibilities (5 items), Relating to Others (7 items), and Spiritual and Existential Change (6 items). The 25-item measure examines the degree of change participants experienced as a result of cancer on a 5-point scale (0 = I did not experience this change as a result of my cancer; 5 = I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my cancer).

Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R 3.6.2 (R Core Team, 2017), with GPArotation (Bernaards & Jennrich, Reference Bernaards and Jennrich2005) and psych (Revelle, Reference Revelle2017) R packages. An iterative process guided by best-practice guidelines, including internal and external item characteristics, was used to inform item retention decisions (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Sinar and Balzer2002). Selection of the response scale for inclusion in the VOICE measure was informed by the level of participant endorsement on the importance and control scales. EFA was conducted using principal axis factoring (PAF), implementing a direct oblique rotation method. Overall model fit was assessed using goodness of fit criteria including: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Root Mean Square of Residuals (RMSR), and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). The model was considered to have good fit if the RMSEA was <0.06, RMSR < 0.08, and TLI > 0.95, while an RMSEA value of <0.08 was considered an acceptable fit (Browne and Cudeck, Reference Browne, Cudeck, Bollen and Long1993; Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; West et al., Reference West, Taylor, Wu and Hoyle2012). An iterative process was used to determine the exclusion of items based on: factor loadings (<0.30), item communalities, and item-factor correlations, as well as inter-item correlations and Pearson correlations (r < 0.30) between VOICE items and the comparison validation measures (PROMIS-29 subscale T-scores, HHI, FACIT-COST, GSE-SF, C-CARES Care Coordination, PSQ Accessibility and Convenience, PTGI-X). Additionally, the theoretical and practical implications of each item were assessed independently by authors and reconciled in a series of consensus meetings. We sought to retain at least three items per factor, in alignment with recommended practices for latent construct measurement (El-Den et al., Reference El-Den, Schneider and Mirzaei2020).

Results

-

Participant Socio-Demographics. Participants were predominantly female (73%), Non-Hispanic White (76%), and completed a college degree (73%). The average age was 55.6 years (SD = 13.3; range = 18 to 90), and the average time since initial cancer diagnosis was 6 years (range = <1 to 41). The most frequently represented diagnoses included breast cancer (27%) and hematologic cancers (10%; Table 1).

-

Rating scale selection. Participant endorsement for level of importance for the 35 draft VOICE items was high: 21 of 35 items were rated in the highest response categories (Quite a bit or Very much) by 90% or more of participants (average importance rating across 35 items = 85%; range = 32–99%). In contrast, endorsement for level of control for the 35 VOICE items exhibited substantive response variability; with the average rating items in the highest response categories (Quite a bit or Very much) at 63% across all 35 items (range = 26–89%). No item was rated by 90% or more of participants in the highest response categories for control. The ceiling effect in importance ratings, coupled with response variation in control ratings, informed the decision to discontinue the use of the importance ratings and continue with the perceived control rating scale for subsequent analyses in the development of the VOICE measure.

-

Item reduction. Evaluation of EFA results, inter-item correlations, and correlations between the VOICE items and cross-validation measures, described below, led to the exclusion of 16 items, minor rewording of four items, major rewording of one item, and addition of one item, resulting in a final 21-item VOICE measure for confirmatory testing (Table 2).

-

Exploratory factor analysis. EFA supported a 20-item, seven-factor structure: F1: Purpose and Meaning, F2: Functional Capacity, F3: Longevity, F4: Quality Care, F5: Illness Knowledge, F6: Social Support, and F7: Financial Capability (Table 2). The seven factors exhibited strong item-factor correlations ranging from r = 0.75 to 0.88 (Mean = 0.82). Items that had factor loadings <0.30, had low communality, or were not associated with conceptually relevant validation measures, were removed from analyses. The final EFA included 20 items loading across seven factors, explained over half of the variance in the data (54%), and demonstrated good model fit (RMSEA = 0.027, 90% CI = 0.015–0.038; RMSR = 0.01; TLI = 0.982). As the Financial Capability factor was only represented by two items, an additional item was developed (“you can get the medical care that you need no matter how much it costs”) to ensure adequate representation of the conceptual domain for confirmatory validation testing.

-

Inter-item correlations. Inter-item correlations were also used to determine item retention or removal, with highly correlated items removed. For example, the item “maintaining your independence” was dropped due to the high correlation with “being well enough to attend important events” (r = 0.61) and “doing activities you enjoy” (r = 0.57). The item “your medical team coordinates your follow-up appointments and referrals” was also removed due to the high correlation with the items “your health care team understands your values and goals for care” (r = 0.55) and “your medical providers work together to plan your care” (r = 0.52).

-

Correlations with comparison measures. Items with low correlations (r < 0.30) with measures hypothesized to be conceptually relevant were dropped or reworded. For example, “whether you have a strong relationship with God” was dropped because it exhibited low correlations among all cross-comparison measures (M = 0.07), including those expected to have strong correlations (HHI: r = −0.21; PTGI: r = 0.11). Similarly, the item “whether you are offered treatments to provide relief from your symptoms and side effects” was removed due to low correlations with comparison measures, including PROMIS Physical Function (r = 0.15) and PROMIS Pain Interference: (r = 0.21).

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis of interim 20-item pool (N = 623)

h2 = communality. Item-total r = corrected item-total correlation.

Item phrasings were reworded and finalized prior to CFA as follows:

a you live without physical discomfort (pain, nausea, bloating, etc.).

b your medical providers work together to plan your care.

c you understand the short-term and long-term side effects of your treatment.

d you have people you can turn to for help with day-to-day needs.

e you understand the costs of your own illness and treatments.

† An additional item was added to Financial Capability to bring total number of subscale items to 3: you can get the medical care that you need no matter how much it costs.

Phase III: Confirmatory validation analysis

Participants

Participants for the 21-item VOICE confirmatory validation analysis were recruited from September to December 2020, within a larger survey examining patient care experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethics approval was obtained from NORC at the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB00000967; Protocol #20.08.21). Participants were included in the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) if they had complete data for all VOICE and PROMIS-29 items (N = 515).

Measures

Confirmatory validation analysis measures included the 21-item VOICE measure (Appendix 1), socio-demographic and clinical items as described in Phase II, as well as the following scales: PROMIS-29 and HHI (as described above), the Perceived Health Competence Scale (PHCS), the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10©), and the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS-12):

-

Perceived Health Competence Scale (PHCS) measures an individual's capacity to effectively manage their own health outcomes. The eight items assess an individual's sense of competence and control over health-related outcomes and behaviors (e.g., “I'm generally able to accomplish my goals with respect to my health”) on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree), with higher scores reflecting a greater sense of perceived health competence (Shelton Smith et al., Reference Shelton Smith, Wallston and Smith1995).

-

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10©) was used to measure resilience in the sample. The 10-item measure asks participants to indicate how true each statement is of their ability to handle hardships on a 5-point scale (0 = Not true at all; 4 = True nearly all the time). Higher scores reflect greater resilience and ability to handle hardships (Davidson, Reference Davidson2020).

-

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS-12) was used to measure intolerance of uncertainty, which is the tendency to consider the possibility of a negative event occurring as unacceptable (Carleton et al., Reference Carleton, Norton and Asmundson2007). The 12-item short form asks participants to rate statements (e.g., “Unforeseen events upset me greatly”) from 1 (Not at all typical of me) to 5 (Entirely typical of me); higher scores represent greater intolerance.

Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corp, 2016) and R 3.6.2 (R Core Team, 2017), with lavaan (Bernaards & Jennrich, Reference Bernaards and Jennrich2005) and psych (Revelle, Reference Revelle2017) R packages. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the 21 VOICE items. To confirm dimensionality of the shortened scale, CFA was conducted using maximum-likelihood factor extraction, fixing factor loadings for the first indicator in each factor to 1.0. Overall model fit was assessed using goodness of fit criteria including: RMSEA, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). The model was considered to have good fit if the RMSEA was <0.06, CFI > 0.95, SRMR < 0.08, and TLI > 0.95, while an RMSEA value of <0.08 was considered an acceptable fit (Browne and Cudeck, Reference Browne, Cudeck, Bollen and Long1993; Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; West et al., Reference West, Taylor, Wu and Hoyle2012). Internal consistency reliability was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha. Convergent and discriminant validity were evaluated through Pearson correlations with PROMIS-29 subscales, HHI, PHCS, CD-RISC-10, and IUS-12. We hypothesized that poorer quality of life, lower hope, lower health competency, and lower resilience were associated with lower perceived control (Chi, Reference Chi2007; Bárez et al., Reference Bárez, Blasco and Fernández-Castro2009; Gorman, Reference Gorman, Bush and Gorman2018; Seiler & Jenewein, Reference Seiler and Jenewein2019; Thompson, Reference Thompson, Snyder, Lopez, Edwards and Marques2021). Correlations were considered large if r ≥ 0.50, medium if r = 0.30–0.49, and small if r = 0.10-0.29 (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992). Known groups validity was examined using Hedge's g or Glass's delta (used when groups have unequal variance) to estimate effect sizes between identified groups for income (<$40K vs. $40K+ annual income), current cancer status (first time or recurrence vs. remission), metastatic status (no evidence of disease or localized vs. metastatic), currently receiving treatment (yes/no), and Pearson correlations to examine associations with time since cancer diagnosis (modeled continuously). We hypothesized that patients with lower income, as well as those with active or advanced disease (more recent diagnosis; having active cancer, either first time or recurrence; current metastatic disease; currently receiving treatment) would report lower perceived control (Bosma et al., Reference Bosma, Schrijvers and Mackenbach1999; Ranchor et al., Reference Ranchor, Wardle and Steptoe2010; Warren, Reference Warren2010).

Results

-

Participant Socio-Demographics. Participants were predominantly female (75%), Non-Hispanic White (79%), and completed a college degree (72%). The average age was 60 years (SD = 12.2, range = 20–88), and average time since initial cancer diagnosis was 6.5 years (range = <1 to 56 years). The most frequent diagnoses included breast cancer (28%) and hematologic cancers (29%; Table 1).

-

Descriptive Statistics of VOICE Control Ratings. There was variability in participant endorsement across the 21-item VOICE control ratings, with between 19.4% and 76.3% (M = 50.3%) of participants feeling Quite a bit or Very much in control. The five most highly endorsed items were distributed across Purpose and Meaning, Quality Care, and Illness Knowledge, and included: “you understand your own diagnosis” (76.3%), “your life has value and worth” (69.5%), “you see a doctor who specializes in your illness” (67.0%), “you understand how to manage your own symptoms and side effects” (65.6%), and “you have a sense of purpose in your life” (64.1%). The five least endorsed items were concentrated in the Longevity and Financial Capability factors, including: “your illness does not get worse or come back” (19.4%), “you have a long life” (22.7%), “you understand the costs of your own illness and treatments” (30.5%), “you have other treatment options if your treatment does not work” (35.8%), and “you can get the medical care that you need no matter how much it costs” (40.5%).

-

Confirmatory Factor Analysis. CFA was used to assess the factor structure identified in the EFA in Phase II. The overall model of the 21-item VOICE measure demonstrated good fit as indicated by fit indices (n = 515; RMSEA = 0.078, 90% CI = 0.072–0.084; SRMR = 0.051; TLI = 0.871; CFI = 0.897, χ2(168) = 699.78, p < 0.01).

-

Internal Consistency Reliability. The full 21-item VOICE scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.93 (Table 3). Cronbach's alphas for the seven factors ranged from near Acceptable (α = 0.67 for Functional Capacity and Longevity) to Good (α = 0.89 for Purpose and Meaning). Average inter-item correlations within the seven factors ranged from 0.43 to 0.73, indicating moderate to high correlations.

-

Convergent and Discriminant Validity. VOICE total score was moderately to strongly correlated with all PROMIS-29 subscales in the expected direction (r = ±0.33 to 0.51, ps < 0.001). VOICE was also strongly correlated with other related measures of interest including HHI (r = 0.61), PHCS (r = 0.61), and CD-RISC-10 (r = 0.52, ps < 0.001) in the expected direction. Individual factors were moderately to strongly correlated with PROMIS-29 subscales of similar concepts as well as the PHCS and CD-RISC-10. In contrast, VOICE total score and subscales were only weakly correlated with the IUS-12, supporting measure discriminant validity (Table 4).

-

Known-Groups Validity. Several participant group comparisons supported known-groups validity based on the total 21-item VOICE score as well as subscales of relevance: annual income (collapsed into <$40K vs. $40K+); current cancer status (collapsed into first time or recurrence vs. remission), current active cancer treatment (yes vs. no), current metastatic disease, and years since diagnosis (continuous) (Table 5). The directional differences of known-group means were consistent with hypothesized directions — with lower scores suggesting lower perceived control for those participants reporting lower annual income, experiencing active cancer, having current metastatic disease, and currently receiving treatment. There were also small but significant associations between perceived control and time since diagnosis, where more recently diagnosed participants reported lower control.

Table 3. 21-item VOICE total scale and factor descriptive characteristics, intercorrelations, and internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's α) (N = 515)

a Mean(SD) based on averaged factor scores.

* p < 0.001.

Table 4. Pearson correlations between 21-item VOICE total scale, VOICE factors, and confirmatory validation measures (N = 515)

Values reported are Pearson correlation coefficients (r); All ps < 0.001 for Pearson correlations.

HHI, Herth Hope Index; PCHS, Perceived Health Competence Scale; CDRS, Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale; IUS, Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale.

Table 5. Known groups validity analyses for 21-item VOICE total scale and factors

Missing values excluded from analyses. Effect size calculations: Hedge's g calculated due to unequal sample sizes; Glass's delta calculated for groups who do not have equal variance.

***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05, NS, not significant.

a Equal variances not assumed based on Levene's test.

Discussion

The current study describes the psychometric development and testing of VOICE, a multi-dimensional measure of patients’ perceived control over personal priorities within their cancer experience. An iterative and comprehensive process was used with extensive stakeholder participation to develop, test, refine, and validate items and factors representing key priorities for people with cancer. Our findings provide support for a 21-item measure comprised of seven related dimensions: Purpose and Meaning, Functional Capacity, Longevity, Quality Care, Illness Knowledge, Social Support, and Financial Capability. VOICE has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including adequate internal consistency reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and known groups validity, and provides unique insights into the cancer experience.

Grounded in the perspectives of people with cancer, VOICE measures both individual and interpersonal domains of the cancer experience that can impact overall quality of life, addressing ongoing gaps in adequately measuring patients’ perspectives over personal priorities in their cancer experience (Mollica et al., Reference Mollica, Lines and Halpern2017; Warsame & D'Souza, Reference Warsame and D'Souza2019). By asking respondents about their sense of control over specific domains, VOICE offers greater specificity than general measures of control (Pearlin & Schooler, Reference Pearlin and Schooler1978; Wallston et al., Reference Wallston, Wallston and DeVellis1978) and can be used to identify key modifiable areas to address in managing patient health and well-being (Anatchkova et al., Reference Anatchkova, Donelson and Skalicky2018). As such, when used in real-world clinical settings, VOICE results shared between the patient and provider have the potential to facilitate patient-provider communication, improve shared decision-making, and improve the perceived quality of care (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Molloy and Wilkinson2015; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Manhas and Howard2018). Within supportive care and community-based research settings, VOICE has the potential to guide the development and systematic evaluation of supportive interventions that can lead to greater patient empowerment, increased adaptation, and improved overall well-being (Golant et al., Reference Golant, Zaleta, Ash-Lee, Breitbart, Butow, Jacobsen, Lam, Lazenby and Loscalzo2021).

Strengths in developing this measure include the use of an iterative approach that leverages patient perspectives across all steps of scale development. Other strengths include participation by a broad sample of patients across diverse cancer care settings, diagnoses, and geographic areas. Decisions about item retention were guided by a systematic consideration of internal and external characteristics of items (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Sinar and Balzer2002). We also used a robust battery of psychometrically validated cross-validation measures to examine scale multidimensionality and construct validity across the total scale and its factors. Future research will examine VOICE implementation across real-world clinical and community settings to determine how the measure can be used optimally to improve psychosocial and health outcomes, especially among underrepresented and underserved communities.

Limitations include self-selected samples of participants who are predominantly female, White, and well-educated, which may limit the generalizability of some findings with a more diverse socio-economic population. This sample is not representative of all cancer patients across the U.S., and there was a greater representation of breast cancer patients. However, given the function of VOICE to identify individuals with lower personal control over key aspects of their cancer experience, the measure has the potential for identifying opportunities to improve the care experiences of underrepresented patients who may experience barriers in accessing care (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Davis and Bluethmann2019). Of note, acute end-of-life priorities and needs were not included in the creation of VOICE due to the unique and specific scope of this phase of the cancer experience. While scale items were evaluated through cognitive interviews for clarity and comprehension, formal readability assessment was not conducted during item generation; quantitative assessment of the final VOICE measure indicates a 6–7th grade Flesch-Kincaid reading level. Administering a 21-item measure may contribute to participant burden in some settings; however, VOICE includes distinct factors to support flexible administration in settings where it may be desirable to focus on a narrower range of constructs. Future psychometric evaluation will seek to determine test-retest reliability (Holmbeck & Devine, Reference Holmbeck and Devine2009), the reliability of VOICE in detecting within-person change (Cranford et al., Reference Cranford, Shrout and Iida2006), and psychometric properties when administering select factors only (i.e., modularization). Additional future validation efforts will seek to evaluate criterion validity, such as the extent to which perceived control as measured by VOICE predicts key behavioral indicators such as patient engagement and health care utilization (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Miller and Arora2012).

In summary, VOICE creates a platform for elevating patient perspectives across the cancer continuum, identifying pathways for empowerment and hope. Future goals for research and implementation of VOICE include further testing the measure in real-world clinical and community settings with diverse populations across the cancer continuum, as well as longitudinal validation studies of the responsiveness of VOICE in detecting and benchmarking meaningful changes in perceived control over time. VOICE has the potential to provide unique information on key personal priorities to guide communication and shared decision-making between people with cancer and health care providers, in addition to guiding the development of interventions and programs designed to empower and improve personal control, and consequently improve the quality of life for people with cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Deborah Bandalos, Branlyn DeRosa, and Julie Olson for their scientific guidance and Jemeille Ackourey, Kelly Clark, our advocacy partners, and Cancer Support Community network partners, including Cancer Support Community and Gilda's Club locations, for their recruitment support.

Funding

Support for this work was provided by Pfizer Oncology and Genentech.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Zaleta: Institutional research funding from: Astellas Pharma, Boston Scientific Foundation, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, Pfizer Oncology, Seattle Genetics. Dr. Fortune: Institutional research funding from: AbbVie, Amgen Oncology, AstraZeneca, Astellas Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Lilly Oncology, Merck & Co, Inc, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co, Takeda Oncology. Dr. Miller: Institutional research funding from: GlaxoSmithKline, Merck & Co., Inc., Takeda Oncology. Dr. Yuen, Ms. McManus, Dr. Hurley, Dr. Golant, Ms. Goldberger, Dr. Shockney, Dr. Buzaglo: No disclosures.