Introduction

Among adolescents and young adults (AYAs), cancer is the most common disease-related cause of death (American Cancer Society, 2020). AYAs with cancer face poorer medical outcomes as a result of many factors including the stage of development (Warner et al., Reference Warner, Kent and Trevino2016), socioeconomic impact of health insurance and access to care (Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg, Kroon and Chen2015; Alvarez et al., Reference Alvarez, Keegan and Johnston2018), and biologic differences in cancer types (Tichy et al., Reference Tichy, Lim and Anders2013; Tricoli and Bleyer, Reference Tricoli and Bleyer2018; Tricoli et al., Reference Tricoli, Boardman and Patidar2018). AYAs living with cancer and those living with other potentially life-limiting conditions are in a transitional phase of life with unique developmental and psychosocial needs that can go unrecognized or unmet over the trajectory of their care. Having to navigate illness while experiencing an emergence of independence, identity development, and relational maturation (Zeltzer, Reference Zeltzer1993; Eiser et al., Reference Eiser, Penn and Katz2009; Zebrack, Reference Zebrack2011; Coccia et al., Reference Coccia, Altman and Bhatia2012) can be further challenged when AYAs are left out of treatment discussions and decisions (Zebrack et al., Reference Zebrack, Chesler and Kaplan2010; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Haase and Broome2017).

These medical challenges and psychosocial vulnerabilities point to a critical need for effective end-of-life (EoL) communication, especially alongside disease progression or a poor prognosis (Sansom-Daly et al., Reference Sansom-Daly, Wakefield and Patterson2020). AYA patients want to be informed, involved in decision-making (Hinds et al., Reference Hinds, Drew and Oakes2005; Lyon et al., Reference Lyon, Garvie and McCarter2009; Pousset et al., Reference Pousset, Bilsen and De Wilde2009; Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Zadeh and Battles2012; Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Wiener and Jacobs2021), have the ability to choose and decline treatment, and determine their care plans including how they will be remembered after death (Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Zadeh and Battles2012). Goals of care conversations and more formal advance care planning (ACP) discussions allow for safer processing of hopes, fears, and preferences for care (Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Wiener and Jacobs2021). Including AYAs in EoL conversations has been shown to be helpful with informing decisions, alleviating distress, improving perceived quality of care (Mack et al., Reference Mack, Hilden and Watterson2005), and potentially improving quality of life (QoL) through the attention to personal values, beliefs, and preferences (Jankovic et al., Reference Jankovic, Spinetta and Masera2008; Barfield et al., Reference Barfield, Brandon and Thompson2010; Kane et al., Reference Kane, Joselow, Duncan, Wolfe, Hinds and Sourkes2011; Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Zadeh and Battles2012). Unfortunately, ACP discussions often occur too late or during an acute clinical deterioration where there is insufficient time to consider goals and values (Snaman et al., Reference Snaman, McCarthy and Wiener2020) and when a patient's incapacity may leave family members and clinicians struggling to make patient-centered decisions (Brudney, Reference Brudney2009). AYAs who are not provided the opportunity to talk about EoL issues may also be less likely to die at their location of choice (e.g., at home) (Tang and McCorkle, Reference Tang and McCorkle2001) and more likely to experience intrusive procedures in the days and weeks leading up to their death (Mack et al., Reference Mack, Chen and Cannavale2015b, Reference Mack, Chen and Boscoe2015a; Kaye et al., Reference Kaye, Gushue and DeMarsh2018). Conversations about EoL care have also been shown to decrease parental decisional regret (DeCourcey et al., Reference DeCourcey, Silverman and Oladunjoye2019; Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Roberts and Catarozoli2020).

The Institute of Medicine has recommended ACP conversations be routine and structured aspects of standard care (Kirch et al., Reference Kirch, Reaman and Feudtner2016). The provision of palliative care, which includes ACP, is also an evidence-based standard of care in pediatric cancer (Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Heinze and Kelly2015). Yet, gaps in implementing ACP with AYAs have been well recognized (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Hammel and Edwards2008; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Temin and Alesi2012; Kassam et al., Reference Kassam, Skiadaresis and Habib2013; Pinkerton et al., Reference Pinkerton, Donovan and Herbert2018), particularly when it comes to communication about EoL planning preferences. Studies have shown that less than 3% of AYAs participate in EoL planning conversations without clinician prompting (McAliley et al., Reference McAliley, Hudson-Barr and Gunning2000; Lyon et al., Reference Lyon, McCabe and Patel2004, Reference Lyon, Jacobs and Briggs2014; Liberman et al., Reference Liberman, Pham and Nager2014). Lack of comfort and skills, time constraints, fear of causing anxiety or further distress to the AYA, and deep care and optimism have been noted as reasons why clinicians have not had these conversations (Hilden et al., Reference Hilden, Emanuel and Fairclough2001; Granek et al., Reference Granek, Tozer and Mazzotta2012, Reference Granek, Krzyzanowska and Tozer2013; Mack and Smith, Reference Mack and Smith2012; Kassam et al., Reference Kassam, Skiadaresis and Habib2013; Rosenberg and Wolfe, Reference Rosenberg and Wolfe2013; Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Zadeh and Wexler2013; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Young and Herbert2017). Even when the person has advanced disease, research has shown that many clinicians continue to avoid these discussions due to a fear of destroying hope or causing harm (Hancock et al., Reference Hancock, Clayton and Parker2007a; Almack et al., Reference Almack, Cox and Moghaddam2012; Abernethy et al., Reference Abernethy, Campbell and Pentz2020).

The constantly evolving nature of oncology treatment, alongside complex decisions AYAs and their families face requires the development and use of novel tools to invite the AYA voice and role in decision-making (Snaman et al., Reference Snaman, McCarthy and Wiener2020). Voicing My CHOiCES (VMC), a research-informed ACP guide (Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Zadeh and Battles2012; Zadeh et al., Reference Zadeh, Pao and Wiener2015), can assist Health Care Provider (HCP) in having these discussions. Since VMC became available in 2012 (through Aging with Dignity), over 54,000 copies have been requested from 42 countries. However, there is no outcome data associated with VMC. We sought to determine whether engaging in ACP using VMC was associated with changes in communication about ACP with family and/or HCPs, generalized anxiety, anxiety about ACP, and social support. We hypothesized that the utilization of a formal tool to guide ACP would measurably increase communication about EoL care preferences and alleviate anxiety surrounding ACP.

Methods

Study recruitment and enrollment

Eligible participants were AYAs aged 18–39 years, English-speaking, and receiving treatment for cancer or another chronic medical illness at one of seven participating study sites. An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score of 3 or less was required. A convenience sample was achieved by approaching eligible participants in outpatient clinics or inpatient units by a study investigator. The study was approved by the NIH Institutional Review Board and the IRB at each of the participating sites between 2014 and 2019, during which data were collected.

Study procedures

First, each participant completed a baseline assessment describing the communication they have had about ACP with family members and HCPs. They also completed measures of generalized anxiety, anxiety pertaining to ACP, and social support. Together with the study investigator, participants critically reviewed each page of VMC before then completing three pages of the document, one being the page designating a health care proxy and then two pages of the participant's choice. Then, after the completion of the three pages, participants again rated their anxiety regarding EoL planning. This study portion took approximately 60–75 min to complete. The third data collection point occurred 1 month later when participants repeated the measures related to communication about ACP, generalized anxiety, anxiety pertaining to ACP, and social support. Participants were also asked whether they shared what they had completed in VMC with either a family member or one of their HCPs. This study portion took approximately 20–25 min to complete. Procedure training consisted of an in-person, virtual, or phone session with the sponsor site (LW or SB) where a training manual was reviewed in detail and sample case scenarios were discussed.

Data collected

Patient questionnaires included a demographic questionnaire, standardized measures, and additional questions developed by the primary study team derived from clinical experience and literature review. To assess communication about ACP, participants were asked: “Have you ever talked with your family about what your wishes or preferences might be if treatments were no longer working well for you?” If they had not had such a discussion, participants were provided a list of potential barriers and an open-text response option about barriers to ACP communication and anything that would make these discussions easier for them. The same questions were asked about communication with HCPs.

Generalized anxiety was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams2006; Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Decker and Muller2008). The responses to seven questions are constructed on a 3-point scale from “Not at all” to “Nearly every day” and the survey is scored on a 0–21 point scale. A score of 5–9 indicates mild anxiety, 10–14 indicates moderate anxiety, and 15 or more indicates severe anxiety.

Anxiety pertaining to ACP was measured by asking participants: “How much anxiety do you feel about planning for your care in the case that treatment is no longer effective for you?” Response options were “no anxiety,” “a little anxiety,” “moderate anxiety,” or “a lot of anxiety”.

Perceived social support was assessed using a 6-item subscale of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), a reliable and valid self-report scale that assesses health-related QoL in multiple life domains, including social support (Cella et al., Reference Cella, Tulsky and Gray1993, Reference Cella, Hahn and Dineen2002; Webster et al., Reference Webster, Cella and Yost2003; Luckett et al., Reference Luckett, Butow and King2010). The items specifically address perceived support from and closeness to family and friends, as well social acceptance of, and satisfaction with, communication surrounding their illness. Items are endorsed on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much.”

ECOG, used to measure performance status, describes a patient's level of functioning (performance status) in terms of their ability to care for themself, daily activity, and physical ability. Categories range from 0 (fully able to carry all pre-disease performance) to 5 (dead) (Oken et al., Reference Oken, Creech and Tormey1982).

Voicing My CHOiCES is an ACP guide developed based on extensive feedback from AYAs living with cancer and other serious illnesses, clinical expertise, and relevant literature (Chochinov, Reference Chochinov2002; Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Zadeh and Battles2012, Reference Wiener, Zadeh and Wexler2013; Zadeh et al., Reference Zadeh, Pao and Wiener2015). There are 10 sections that comprise VMC (Table 1). The format includes checkboxes for the AYA to endorse items and open spaces for elaboration. For the purposes of this study, each section within the document was presented as a separate “module,” where the administrator provided a brief overview of the section. Conversation was then tailored to the AYA's concerns at the time and assistance in completing the document was provided as needed/desired by the AYA.

Table 1. Description of the sections of Voicing My CHOiCES

Analysis

Mean scores on the generalized anxiety and communication scales were compared between baseline and 1-month follow-up, using paired-samples t-tests. In order to assess the effect completion and discussion of VMC had on ACP-specific anxiety, paired-samples t-tests were conducted between baseline and immediate follow-up, between immediate follow-up and 1-month follow-up, and between baseline and 1-month follow-up. Qualitative analyses were conducted on open-ended free-text narrative responses. These responses were analyzed by three authors (SB, AF, LW) to identify common themes. The authors met to refine themes and to develop codes for qualitative analysis (Macqueen et al., Reference Macqueen, McLellan-Lemal and Kay1998). Free-text responses were then coded in parallel (SB, AF) with differences resolved through discussion with another author (LW) (Malterud, Reference Malterud2001).

Results

Participant demographics

Of 185 patients approached from April 2014 to January 2020, 149 (80.5%) agreed to participate at baseline and 127 (68.6%) participated at 1-month follow-up (with slightly different numbers completing each follow-up measure, see below). Reasons for non-participation at baseline (n = 36) included: not interested/not wanting to partake in non-medical studies (36.1%), time constraints (22.2%), not feeling up to it/health issues (13.9%), did not feel it was necessary (2.8%), and did not want to talk about death (2.8%). Sample characteristics can be found in Table 2. Just over half were male, the average age was 26.7 years, 64.4% were Caucasian, and 23.5% were Hispanic. Just under three-quarters of the sample had a cancer diagnosis; 22.8% rated their health as not good or poor. At baseline, there was no significant difference in ECOG performance status between participants diagnosed with cancer and other serious conditions.

Table 2. Description of sample n = 149

Conversations with family members and HCP at baseline

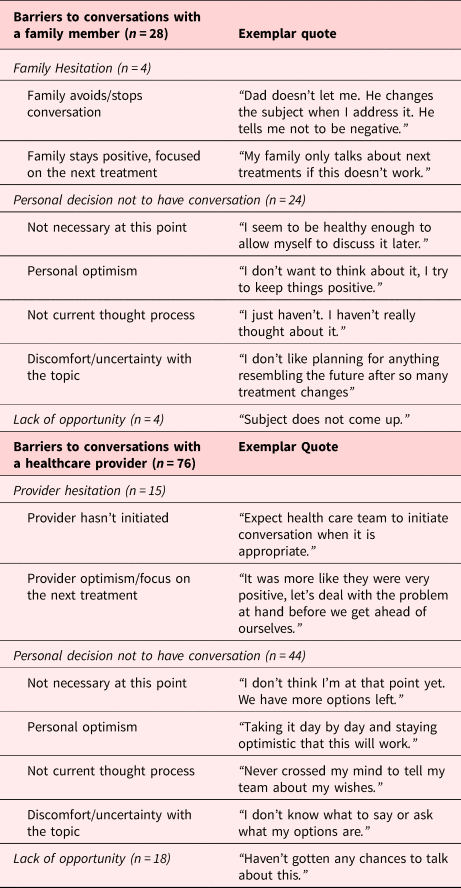

At baseline, just over half of the 149 original participants (50.3%, n = 75) reported that they previously had a conversation about EoL preferences with a family member. Those who had not had the conversation were asked to identify, from six response options, reasons for not doing so (Tables 3 and 4). Thirty-eight per cent of participants (n = 28) cited an “other” reason for not discussing the EoL topic. These responses fell into three main themes, (1) family hesitation towards EoL conversations, (2) personal decision/choice to not have the conversation, and (3) lack of opportunity to have the conversation (Table 4).

Table 3. Advance care planning conversations with family members and HCP and barriers to conversations (n = 149) at baseline

Table 4. Other reasons for not having advance care planning conversations with family members and HCP at baseline

At baseline, 19.5% (n = 29) indicated they had previously engaged in this conversation with an HCP. The reasons endorsed for not having those conversations are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Sixty-eight per cent of participants (n = 76) cited an “other” reason for not discussing the topic. Themes within the free-text responses included (1) provider hesitation towards EoL conversations, (2) personal decision/choice to not have the conversation, and (3) lack of opportunity to have the conversation.

Conversations with family members and HCP at 1-month follow-up (changes)

One month after completing the baseline measure and reviewing the VMC tool, 127 participants answered the follow-up questions about talking with family members and 124 answered the question about talking with HCP. Overall, 65.1% (n = 84) of participants had shared what they wrote in VMC with a family member and 8.9% (n = 11) shared with an HCP. Of those who had not discussed their wishes with a family member at baseline, 51.5% (n = 35) had subsequently engaged in the conversation. Most individuals (88.6%, n = 31) reported that they would not have shared this information with a family member had they not been participating in the study.

Of those who had not discussed their wishes with an HCP at baseline and also completed this question at follow-up (n = 97), 7.2% (n = 7) had subsequently engaged in the conversation. All (100%, n = 7) reported that they would not have shared this information with an HCP had they not been participating in the study.

Having shared what participants wrote in VMC with family at follow-up was not significantly associated with gender, race, ethnicity, employment status, religion, religiosity, health status, income, health insurance status, parent status, or relationship status. However, those with cancer were more likely to have shared what they wrote at follow-up with a family member (70.5%) than those with a different medical condition (48.5, χ 2 = 5.2, p < 0.05).

Anxiety, EoL care planning anxiety, and social support

Generalized anxiety

One hundred twenty-two participants completed the generalized anxiety measure at both baseline and 1-month follow-up. Of those at baseline, 48.4% (n = 59) participants reported minimal anxiety (score of less than 5), 31.1% (n = 38) reported mild anxiety, 13.9% (n = 17) reported moderate anxiety, and 6.6% (n = 8) reported severe anxiety on the GAD-7. At follow-up, 56.6% (n = 69) participants reported minimal anxiety, 29.5 (n = 36) reported mild anxiety, 10.7% (n = 13) reported moderate anxiety, and 3.3% (n = 4) reported severe anxiety. Treating the variable continuously, a paired-samples t-test indicated a significant decrease in generalized anxiety between baseline and 1-month follow-up (t = 2.8, df = 121, p < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the change in GAD-7 results between baseline and 1-month follow-up for those who discussed what they wrote in VMC with a family member or HCP versus those who did not.

Social support

The FACT-G was completed by 84 participants at both baseline and follow-up. The mean score at baseline was 19.5 versus 19.2 at follow-up. A paired-samples t-test indicated no significant change in perceived social support between baseline and 1-month follow-up (t = 0.6, df = 83, ns).

ACP anxiety

One hundred nineteen participants completed the ACP anxiety measure at all three time points. At baseline, approximately half of the sample indicated “moderate” or “a lot” of anxiety related to ACP. After reviewing and completing the VMC pages, just less than one third reported “moderate” or “a lot of anxiety”. The levels remained almost the same at 1-month follow-up (Table 5). Paired-samples t-tests, testing changes in mean scores between Times 1 and 2, Times 1 and 3, and Times 2 and 3 revealed significant decreases between Times 1 and 2 (t = 5.9, df = 118, p < 0.001) and Times 1 and 3 (t = 4.9, df = 118, p < 0.001), but no difference between Times 2 and 3 (t = 0.1, df = 118, ns). There was no significant difference in the change in ACP anxiety between baseline and 1-month follow-up for those who discussed what they wrote in VMC with a family member or HCP versus those who did not.

Table 5. End-of-life planning at baseline, immediate follow-up, 1-month follow-up (among those who completed all three time points, n = 119)

Discussion

This is the first study of AYAs living with cancer or other serious conditions that examined outcomes after engaging in ACP using VMC. Our hypothesis that the utilization of a formal tool to guide ACP would measurably increase communication about EoL care preferences and alleviate anxiety surrounding ACP was supported. Just over half of the participants reported having had an ACP conversation prior to participating in the study. While 44.6% did not think the conversation was necessary at the time of the study, after reviewing and completing pages of VMC, half of the participants who had not spoken to a family member about ACP, then did so. This suggests the benefit of having a document that addresses difficult issues such as EoL care preferences, including how patients would want to be remembered immediately and in the years following death, to guide such a discussion. Having a provider to help facilitate conversations based on information reported in an age-appropriate document may also be especially helpful. Incorporating meaningful engagement of and connection with loved ones is an important step in improving EoL communication to potentially limit the regret and trauma families can experience after death (Janvier et al., Reference Janvier, Barrington and Farlow2014; Brighton and Bristowe, Reference Brighton and Bristowe2016; Ulrich et al., Reference Ulrich, Mooney-Doyle and Grady2018; Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Roberts and Catarozoli2020).

While the increase in communication with family about ACP after reviewing and completing portions of VMC is encouraging, we were discouraged to note how few participants had talked to their HCP before or after participating in the study. Often patients and their family members will wait for the topic to be raised by their clinician (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, Butow and Tattersall2005; Brighton and Bristowe, Reference Brighton and Bristowe2016), while clinicians rely on patients and relatives to start the conversation. This can result in a perpetual cycle of non-discussion (Hancock et al., Reference Hancock, Clayton and Parker2007a; Almack et al., Reference Almack, Cox and Moghaddam2012), a missed opportunity (Knutzen et al., Reference Knutzen, Sacks and Brody-Bizar2021), and an environment that fosters false hope and expectations in affected AYAs and their families (Feudtner, Reference Feudtner2007). This cycle can be fueled by multiple barriers, including prognostic uncertainty, fear of the impact on patients, navigating patient readiness, and feeling inadequately trained for, or unaccustomed to, such difficult discussions (Hancock et al., Reference Hancock, Clayton and Parker2007a, Reference Hancock, Clayton and Parker2007b; Momen and Barclay, Reference Momen and Barclay2011; Almack et al., Reference Almack, Cox and Moghaddam2012; De Vleminck et al., Reference De Vleminck, Pardon and Beernaert2014; Pfeil et al., Reference Pfeil, Laryionava and Reiter-Theil2015; You et al., Reference You, Downar and Fowler2015). Additional deficits in communication may stem from limited use of evidence-based standards and reliance on “on-the-job-learning” (Feraco et al., Reference Feraco, Brand and Mack2016).

Most participants (88.6%) reported they would not have shared the preferences they documented in VMC with either a family member or HCP had they not been participating in the study. This highlights the need for practitioners to familiarize themselves with tools/interventions, such as VMC, to help facilitate ACP conversations outside of the research setting. Prioritizing appropriate communication training (EPEC, 2019; The Conversation Project, 2020; Vital Talk, 2021), and incorporating ACP discussions into routine care alongside the use of a structured ACP guide, may greatly improve patient-centered EoL care. A recent study found integrating ACP using pages of VMC into an existing resilience-coaching intervention for AYAs with advance cancer both feasible and acceptable (Reference Fladeboe, O'Donnell and BartonFladeboe et al., Reference Fladeboe, O'Donnell and Barton2021).

While we found no significant changes in perceived social support after participating in the study, anxiety was significantly lower 1 month after reviewing and completing portions of VMC. The immediate drop in EoL care planning anxiety (Time 1 to Time 2) which persisted into Time 3, suggests the effect is immediate and sustained at least into the near future. As there were no differences in the change in anxiety between those who had a conversation about what was written in VMC and those who did not, this reduction in anxiety is likely linked to the experience of completing VMC, again underscoring the importance of access to an age-appropriate ACP guide.

As previously reported, our findings suggest that EoL care discussions with AYAs do not cause harm (Wiener et al., Reference Wiener, Zadeh and Battles2012; Reference Fladeboe, O'Donnell and BartonFladeboe et al., Reference Fladeboe, O'Donnell and Barton2021), specifically in terms of increased anxiety, an important psychological patient outcome (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Zhang and Ray2008). Perhaps, these findings can begin to alleviate the concern that many HCPs hold about increasing their patient's anxiety if EoL is raised. AYAs can both acknowledge a potential terminal prognosis and what their personal goals would be for EoL while they continue to hope for a good quality of life, achieve personal goals, or live longer than expected (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, Hancock and Parker2008).

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to examine outcome data following the use of an ACP guide developed specifically for AYAs. The study was administered nationally across varying institutions and included AYAs with a variety of serious conditions.

Several study limitations are important to note. The study included English-speaking participants, limiting ethnic diversity. We did not compare other methods of ACP against VMC as there are no other ACP guides for AYAs available, nor did we compare the outcome measures with care as usual. As expected with seriously ill participants, attrition from baseline to 1-month follow-up occurred. For others, 1-month follow-up may not have been a sufficient time frame to see changes in social support or sustained reduction in anxiety. Missing data at the 1-month follow-up impacts statistical power and may have introduced biased results. Though anxiety decreased significantly between baseline and 1-month follow-up, it is possible that other life events or variables aside from introducing and completing VMC could explain the difference.

Conclusion

Despite recommendations from the Institute of Medicine that ACP conversations be routinely provided as part of care, implementation with AYAs remains inconsistent. While our data suggest that having a document to guide ACP can increase communication with family, this was not the case with HCPs. Perhaps, the reduction in anxiety found following the completion of several pages of an ACP, like VMC, can lessen apprehension around initiating these conversations. Future research should examine ways for ACP to be more consistently introduced to AYAs as this would allow their preferences for care to be heard, respected, and honored.

Data Availability Statement

Lori Wiener, Sima Bedoya, and Haven Battles had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Catriona Mowbray PhD, BSN RN, CPN for her help with IRB procedures and identifying patients and Andrea Gross, MD for her help with identifying and interviewing study participants at Children’s National Research Institute.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute and National Institutes of Health, NIH (LW, SB, HB, AF, MP); Center for Hospice, Palliative Care and End-of-Life Studies at University of South Florida (KAD, LMAT, BBL, MBB). The Center for Hospice, Palliative Care and End-of-Life Studies at University of South Florida had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.