Article contents

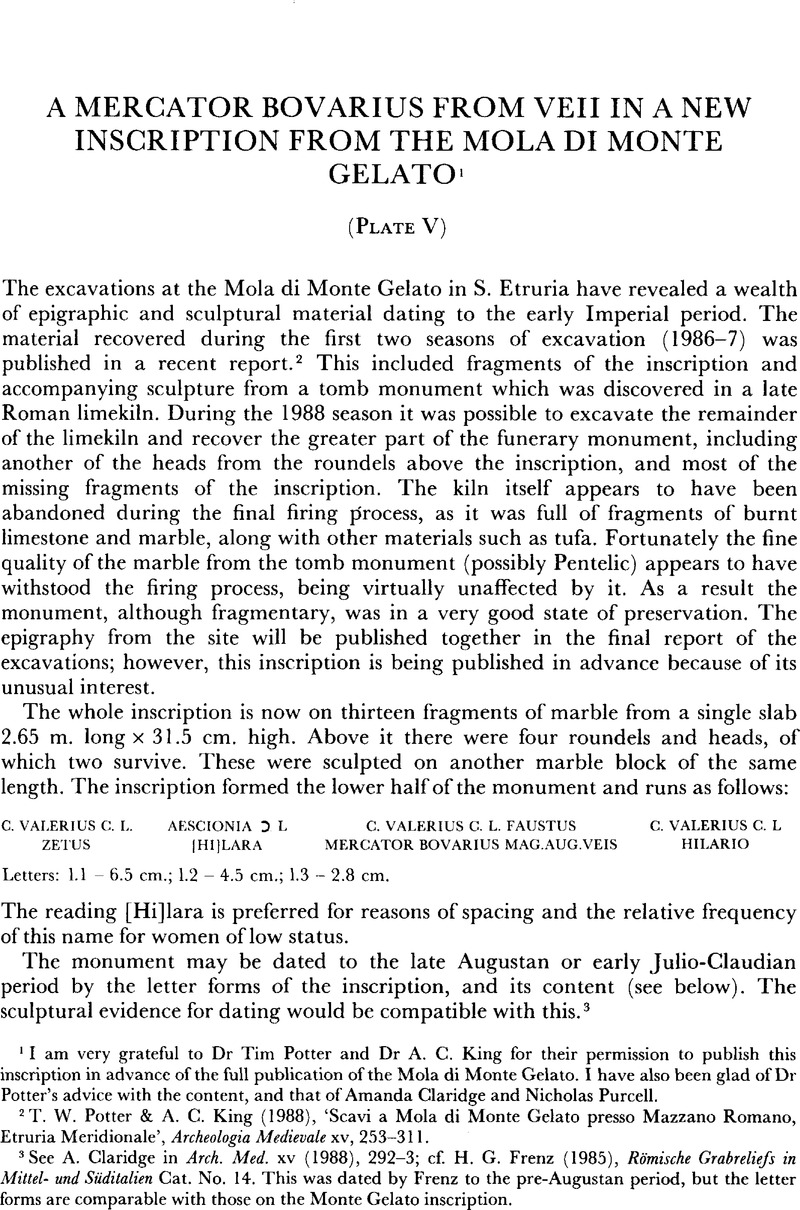

A mercator bovarius from Veii in a new inscription from the Mola di Monte Gelato1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 August 2013

Abstract

- Type

- Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © British School at Rome 1990

References

2 Potter, T. W. & King, A. C. (1988), ‘Scavi a Mola di Monte Gelato presso Mazzano Romano, Etruria Meridionale’, Archeologia Medievale xv, 253–311Google Scholar.

3 See Claridge, A. in Arch. Med. xv (1988), 292–3Google Scholar; cf. Frenz, H. G. (1985), Römische Grabreliefs in Mittel- und Süditalien Cat. No. 14Google Scholar. This was dated by Frenz to the pre-Augustan period, but the letter forms are comparable with those on the Monte Gelato inscription.

4 See Kleiner, D. E. E. (1976), Roman Group Portraiture and Frenz (1985)Google Scholar.

5 For examples from Rome and its hinterland see Kleiner (1976), Cat. Nos. 20, 48, 78; from elsewhere in Italy, Frenz (1985), Cat. Nos. 52, 135.

6 Frenz (1985), Cat. No. 12 (head for Civita Castellana), No. 14 (monument from the Via Cassia).

7 See Kleiner (1976), 39 & 41–2 and Cat. No. 45, where both the males represented in the sculpture are described as medici in the inscription. It would therefore seem likely that if Zetus and Hilario had been involved in the cattle trade, this would probably have been mentioned in the inscription.

8 The grain supply of Rome is discussed by Rickman, G. (1980), The Corn Supply of Ancient RomeGoogle Scholar and by Garnsey, P. (1988), Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World, 231–9CrossRefGoogle Scholar. The supply of meat is mentioned by Louis, P. (1927), Ancient Rome at Work, 170Google Scholar, and by Loane, H. J. (1938), Industry and Commerce in the City of Rome, 28–9Google Scholar; 127.

9 The cattle trade appears to have been a fairly lucrative occupation; C. Caecilius Isidorus, a freedman who died in 8 B.C., stated in his will that he left 3600 pairs of oxen, 257,000 other cattle and 60 million sesterces in cash, demonstrating the great wealth he had acquired, partly from the cattle trade (Pliny, NH XXXIII 135Google Scholar); Columella states that cattle farming was a very profitable enterprise (de Re Rustica VI Pref. 3–5), whilst Cato believed that raising cattle was the most profitable part of an estate (Cicero, , de Officiis II 89Google Scholar). Loane (1938, 127 n. 50) states that the mercator bovarius Q. Brutius was ‘obviously a man of some position’. For the recent publication of the epitaph of M. Valerius Celer, a bub(u)larius, from Rome (Via Portuensis) see Bull. Comm. 90 (1985), 436Google Scholar.

10 All are from Etruria; CIL XI 2631, 3083, 3135, 3200Google Scholar; Notizie degli Scavi (1938), 5–7Google Scholar.

11 12 B.C. is the earliest dated reference to a Magister Augustalis, at Nepi, , (CIL XI 3200Google Scholar), and at some time between 2 B.C. and the death of Augustus in A.D. 14 Seviri Augustales are recorded at Veii, , (CIL XI 3782)Google Scholar. The development of the different offices of the imperial cult is traced by L. R. Taylor (1914), Augustales, Seviri Augustales, and Seviri: A Chronological Study, TAPA xlv, 231–53Google Scholar.

12 CIL VI 200.iv.10 (Rome)Google Scholar; 11181 (Rome); X 2391 (Puteoli); XI 3798 (Veii).

13 For municipes extramurani see Ward-Perkins, J. B. (1961), ‘Veii, The Historical Topography of the Ancient City’, PBSR xvi, 59Google Scholar; Liverani, P. (1987), Municipium Augustum Veiens, 91–2Google Scholar.

14 See Liverani (1987), 90.

15 This occupation is illustrated by an inscription of Urbanus, Q. Petronius, Notizie degli Scavi (1877), No. 263Google Scholar.

16 Another inscription discovered in the present excavations at Monte Gelato, a tombstone of a Herennia dating to the early first century A.D., might suggest a possible connection between the site and M. Herennius Picens, consul of A.D. 1, and patron of the municipium of Veii, (CIL XI 3797Google Scholar).

17 CIL XI 3805Google Scholar.

- 2

- Cited by