Introduction

Coinfection refers to the concurrent infection of an individual host with at least 2 genetically distinct parasites (Hoarau et al., Reference Hoarau, Mavingui and Lebarbenchon2020) and is more common than single infections in natural populations (Telfer et al., Reference Telfer, Lambin, Birtles, Beldomenico, Burthe, Paterson and Begon2010; McArdle et al., Reference McArdle, Turkova and Cunnington2018). The outcomes of coinfection can differ significantly from that of single infections, as the presence of multiple different parasites alters within-host infection dynamics, thereby influencing disease severity (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Raverty, Lambourn, Huggins, Magargal and Grigg2011). Coinfection is often more costly to hosts than single infection (Bordes and Morand, Reference Bordes and Morand2011). For example, mice infected with Plasmodium berghei and Trypanosoma brucei experienced more severe anaemia and greater mortality than singly infected mice (Ademola and Odeniran, Reference Ademola and Odeniran2016). However, coinfections can also be less detrimental than single infections, as evidenced by the increased survival rates of mice infected with 2 strains of T. brucei brucei compared to those infected with only 1 (Balmer et al., Reference Balmer, Stearns, Schötzau and Brun2009). Improving our ability to accurately predict the impacts of coinfections on wild host individuals would improve our understanding of the evolution and ecology of parasites and hosts, and of the mechanisms by which they may influence populations (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Dunn, Dawson, Hipperson, Horsburgh, Morris, Orsman, Mallord, Grice, Hamer and Eraud2022). However, most studies that focus on the impacts of parasitic infection still only evaluate the effects of single infections (Thumbi et al., Reference Thumbi, Bronsvoort, Poole, Kiara, Toye, Mbole-Kariuki, Conradie, Jennings, Handel, Coetzer and Steyl2014). Of the studies that have investigated coinfections, many focus on experimental infections, which may neglect to account for the various factors that influence infection outcomes in wild populations (Hananeh et al., Reference Hananeh, Radhi, Mukbel and Ismail2022).

Measuring the immune response to parasite coinfection in wild hosts could help to gain a deeper understanding of the direct and indirect fitness-related impacts of coinfection on wild host individuals and populations (Budischak et al., Reference Budischak, Jolles and Ezenwa2012), particularly as immune responses respond quickly to physiological stress and tend to be more sensitive to changes in host condition than standard body fat indices (Budischak et al., Reference Budischak, Jolles and Ezenwa2012). Immune responses are costly to the host, as immune activation and maintenance is energetically expensive (Ots et al., Reference Ots, Kerimov, Ivankina, Ilyina and Hõrak2001) and may lead to autoimmunity (Råberg et al., Reference Råberg, Grahn, Hasselquist and Svensson1998). Immunity is also traded-off against other life-history traits, such as reproduction, which can further reduce fitness by reducing host viability (Baer and Schmid-Hempel, Reference Baer and Schmid-Hempel1999) or parental effort (Råberg et al., Reference Råberg, Nilsson, Ilmonen, Stjernman and Hasselquist2000). The fitness costs of an immune response tend to increase as the response intensifies (Marzal et al., Reference Marzal, Reviriego, de Lope and Møller2007). Therefore, although immune responses are predicted to increase in strength as infection virulence increases (de Lope et al., Reference de Lope, Møller and de la Cruz1998), this does not always occur, as hosts may need to suppress immunity, particularly if they are already experiencing stressful conditions (Hanssen et al., Reference Hanssen, Hasselquist, Folstad and Erikstad2004). Immune responses to coinfection can be even more difficult to predict than immune responses to single infection, due to the influence of parasite–parasite interactions on infection virulence. This is exemplified by the conflicting results obtained from research into the immune response to coinfection. For instance, Vieira-Santos et al. (Reference Vieira-Santos, Leal-Silva, de Lima Silva Padrão, Ruas, Nogueira, Kraemer, Oliveira, Caliari, Russo, Fujiwara and Bueno2021) found that mice coinfected with P. berghei and Ascaris suum had significantly elevated white blood cell (WBC) counts compared to singly infected mice. However, Olifiers et al. (Reference Olifiers, Jansen, Herrera, Bianchi, D'Andrea, Mourao and Gompper2015) detected lower WBC counts in male coatis (Nasua nasua) infected with T. cruzi and T. evansi than in individuals with single infections. This highlights the complexity of coinfection and the need for further investigation into its immune-related impacts.

Avian haemosporidian parasites (genera: Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon) can cause avian malaria and malaria-like disease and are frequently used as models in studies of host–parasite dynamics (Lachish et al., Reference Lachish, Knowles, Alves, Wood and Sheldon2011). Acute infection of the avian host can cause anaemia, lethargy, anorexia and even death (Krams et al., Reference Krams, Suraka, Rantala, Sepp, Mierauskas, Vrublevska and Krama2013; Schoener et al., Reference Schoener, Banda, Howe, Castro and Alley2014), and chronic infections, although often asymptomatic, can impact host life history traits (Knowles et al., Reference Knowles, Palinauskas and Sheldon2010). Research into the immune response to avian malaria infection has generated contradictory results. Some studies have reported increased WBC counts in response to haemosporidian infection (e.g. Wojczulanis-Jakubas et al., Reference Wojczulanis-Jakubas, Jakubas, Czujkowska, Kulaszewicz and Kruszewicz2012; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Cornet, Merrill, Kunkel, Tsunekage and Ricklefs2015), whereas others have detected no difference in haematological parameters (Krams et al., Reference Krams, Suraka, Rantala, Sepp, Mierauskas, Vrublevska and Krama2013; Vanstreels et al., Reference Vanstreels, Dutra, Ferreira-Junior, Hurtado, Egert, Mayorga, Bhering, Braga and Catão-Dias2019). This variability could in part be attributed to a high prevalence of avian haemosporidian coinfection (Pigeault et al., Reference Pigeault, Cozzarolo, Choquet, Strehler, Jenkins, Delhaye, Bovet, Wassef, Glaizot and Christe2018). Across the 3 genera of avian malaria and malaria-like parasites, there are over 248 species and 5121 lineages (MalAvi Database, accessed 10/05/2024; Bensch et al., Reference Bensch, Hellgren and Pérez-Tris2009). Coinfection with multiple of these genera, species or lineages is common in wild birds, for example, of the 54 infected Great tits (Parus major) sampled by Rooyen et al. (Reference Rooyen, Lalubin, Glaizot and Christe2013), 81.5% were coinfected with at least 2 different haemosporidian genera. Coinfection with multiple different haemosporidian parasites can significantly impact host individuals and has been reported as being more virulent than single infection (Palinauskas et al., Reference Palinauskas, Valkiūnas, Bolshakov and Bensch2011). Therefore, the immune response to avian malaria coinfection could be expected to be greater than that associated with single infections. However, the complexity of within-host parasite–parasite interactions coupled with the minimal amount of research on this topic makes it difficult to form such general conclusions.

Here, we investigate the immune response to coinfection by multiple genera of avian Haemosporidia in a species of wild bird known to have a high prevalence of blood parasites, and thus predicted to have a high prevalence of coinfection. We predict that (1) immune responses will be stronger in singly infected birds than uninfected birds, as single infection can exert significant costs on hosts (Knowles et al., Reference Knowles, Palinauskas and Sheldon2010). We also hypothesize that (2) coinfected birds will exhibit stronger immune responses than singly infected birds, as avian malaria coinfection has been reported as more virulent than single infection (Palinauskas et al., Reference Palinauskas, Valkiūnas, Bolshakov and Bensch2011), and immune responses are expected to increase in intensity where there is potential for greater damage to the host (de Lope et al., Reference de Lope, Møller and de la Cruz1998).

Materials and methods

Blood samples

A total of 128 blood samples were examined during this study, all of which had been previously collected from blackbirds (Turdus merula) at the following sites in Lincolnshire, UK, between 2017 and 2022: North Carlton (53°17′N, 0°34′W), Eagle (53°11′N, 0°41′W), Owmby (53°31′N, 0°22′W), Blankney (53°07′N, 0°24′W), Moorlands (53°12′N, 0°34′W) and Industrial Cottages (53°14′N, 0°33′W). Two blood smears were created from each sample, which were fixed in absolute methanol and stained with Giemsa for 45–50 min following standard protocols. Additional blood was stored at −20°C prior to DNA extraction and subsequent analysis.

DNA extraction and determination of infection status

DNA was extracted from all samples using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The infection status of each sample was determined using a 1-step multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay capable of detecting parasites of the genera Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon as well as the subgenera Haemoproteus and Parahaemoproteus (genus: Haemoproteus) (Ciloglu et al., Reference Ciloglu, Yildirim, Pekmezci, Yetismis, Sursal Simsek, Simsek, Duzlu, Onder, Delibasi Kokcu, Pekmezci and Ellis2023). However, we did not expect to find Haemoproteus parasites in our samples as this subgenus tends to infect birds from the orders Suliformes, Charadriiformes and Columbiformes, rather than Passeriformes (Ciloglu et al., Reference Ciloglu, Yildirim, Pekmezci, Yetismis, Sursal Simsek, Simsek, Duzlu, Onder, Delibasi Kokcu, Pekmezci and Ellis2023). The PCR was set up in total volumes of 10 μL, consisting of 5 μL of commercial multiplex PCR master mix (2 × Qiagen Multiplex PCR Master Mix, Qiagen), 0.2 μL of each primer (10 mm concentration) (Table 1), 2.4 μL of ddH2O and 1 μL of DNA. Reactions were performed in a Bio-Rad T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The PCR protocol began with denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, after which there were 37 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58.9°C for 90 s and 72°C for 30 s, and finally terminal extension at 72°C for 10 min. One positive and one negative control were included for every 10 samples, to ensure DNA had been successfully amplified (positive control) and that no contamination was present (negative control). Positive controls contained 1 μL of DNA from a blood sample confirmed to be naturally infected with Plasmodium, Leucocytozoon and Parahaemoproteus parasites, whereas negative controls contained 1 μL of ddH2O in place of DNA.

Table 1. Names and sequences of all primers used in the 1-step multiplex PCR and Leucocytozoon sequencing PCR, along with product sizes

Amplification products (5 μL) were electrophoretically resolved after 1 h at 120 V in 3% agarose gels. Gels were then post-stained with gel red to prevent the dye from potentially interfering with DNA migration during electrophoresis. During post-staining, gels were placed in a plastic tub containing 100 ml of water and 30 μL of gel red, which was gently agitated for 45 min. After this, gel visualization was carried out using a Syngene InGenius 3 transilluminator (Syngene International, Bengaluru, Karnataka) and GeneSys software (Genesys, Menlo Park, CA, USA). The presence of an amplicon band at the expected size (Table 1) was indicative of infection. Samples were recorded as either uninfected, singly infected or coinfected with parasites belonging to multiple different genera and/or subgenera, and the identity of any parasites present was noted.

Sequence analysis

Positive samples were sent to Macrogen Europe (Amsterdam, Netherlands) to be sequenced, in order to confirm the identity of the parasite strains present. Although the above PCR protocol produced sufficient lengths of Plasmodium and Parahaemoproteus DNA to allow for meaningful sequencing, this was not the case for Leucocytozoon DNA. As such, Leucocytozoon DNA was amplified using Leunew1F and LDRd primers (Table 1) prior to sequencing, which produced a product of length 340 bp. The PCR protocol was as follows: 95°C for 15 min, followed by 34 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min, and finally terminal extension at 72°C for 10 min. This PCR was carried out using the same equipment and reagents as detailed above. Reaction volumes for all reagents were also identical to those mentioned previously, apart from that of ddH2O (3.6 μL in every 10 μL reaction).

Forward sequences were assessed for any errors, trimmed and then aligned using AliView (Larsson, Reference Larsson2014). Sequences of poor quality, where double peaks were present throughout the chromatogram, were not included in any further analysis. Leucocytozoon sequences were queried using the BLAST algorithm for both the MalAvi (Bensch et al., Reference Bensch, Hellgren and Pérez-Tris2009) and GenBank databases to identify the closest matching sequences. Plasmodium and Parahaemoproteus sequences did not overlap the MalAvi region and were therefore only queried against the GenBank database.

Immune activity and infection intensity

Blood smears were assessed under oil immersion at 100× magnification to quantify immune responses and infection intensity. Inspection of each slide was concluded after a total of both 100 WBCs and 10 000 red blood cells (RBCs) had been examined. Each WBC inspected was identified based on standard avian guidelines (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Boardman and Raidal2009). Immune function was then quantified through calculation of standardized WBC counts and heterophil to lymphocyte ratios (H:L ratios), which are used as measures of immune activity (Smits, Reference Smits2007) and chronic stress (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Maney and Maerz2008), respectively. WBC counts were calculated as the number of erythrocytes present for every 100 WBCs and H:L ratio was calculated using the following formula: heterophils/(heterophils + lymphocytes) (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Stockdale, Bradford, McCubbin, Morris, Grice, Goodman and Hamer2017). Infection intensity was measured for each blood smear by counting the number of parasites (all genera) present for every 10 000 RBCs.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out in R version 4.1.1 for Windows (R Core Team, 2021). General linear models with Gaussian error structure were used to examine the relationship between immune activity and infection status. H:L ratio was square root transformed and WBC count log-transformed to achieve normal distributions. To examine the relationship between coinfection status (coinfected or not coinfected) and immune function, models were run with either H:L ratio or WBC count as the dependent variable and coinfection status as a fixed factor. The effect of genera number (0, 1, 2 or 3, a categorical variable) on immune activity was assessed using models run as above but with genera number as a fixed factor. As parasitaemia is known to influence immune activity (Sol et al., Reference Sol, Jovani and Torres2003; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Cornet, Merrill, Kunkel, Tsunekage and Ricklefs2015), this was included as a covariate in the above models. The effect of genera number (0, 1, 2 or 3) on parasitaemia was investigated using a Poisson regression model constructed with parasitaemia as the dependent variable and genera number as a fixed factor. Likelihood ratio tests were used to test the significance of model terms. Sample sizes were too small to facilitate investigation of the effects of infection with specific parasite genera or genus combinations.

Co-occurrence analysis

To test whether coinfecting genera were significantly associated with one another, or whether coinfections occurred at random, we used the R co-occur package (Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Veech and Marsh2016) to test whether the observed frequency of genus co-occurrence is greater or less than expected given the overall prevalence of each genus in the population.

Results

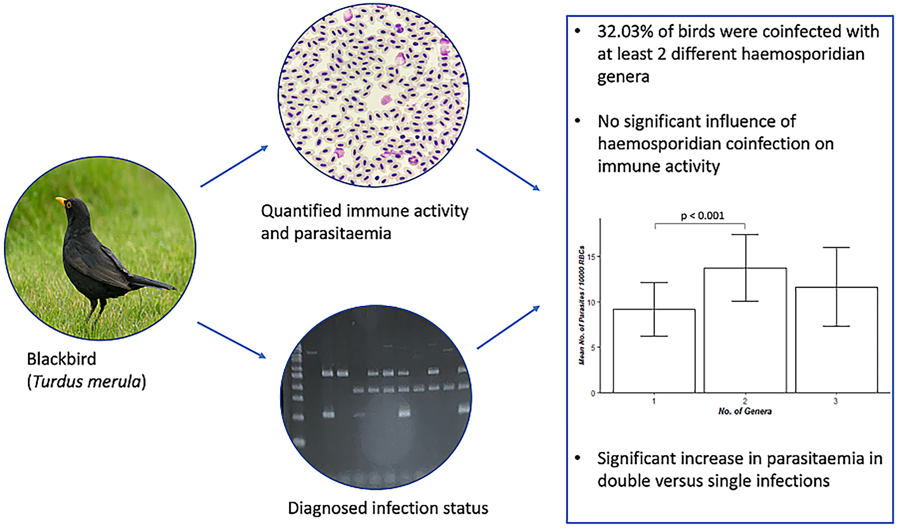

Haemosporidia prevalence

A total of 128 blood samples were examined, of which 26 were uninfected (20.31%), 61 were singly infected (47.66%) and 41 were coinfected with at least 2 different haemosporidian genera (32.03%). Of these 41 samples, 38 were infected with 2 genera (92.68%) and 3 contained all 3 genera (7.32%). Singly infected samples were most commonly infected by Plasmodium spp. (42), followed by Parahaemoproteus spp. (18) and then Leucocytozoon spp. (1) (Fig. 1a). Plasmodium spp.–Parahaemoproteus spp. infections accounted for 89.47% (34) of double infections, whereas Plasmodium spp.–Leucocytozoon spp. and Leucocytozoon spp.–Parahaemoproteus spp. infections were much less common, making up 7.89% (3) and 2.63% (1) of double infections respectively (Fig. 1b). No samples were infected with the subgenus Haemoproteus, and 1 sample infected with Plasmodium spp. was also infected with microfilaria (identified during microscopy). The mean infection intensity amongst birds confirmed as infected through PCR was 8.75 parasites per 10 000 erythrocytes (range 0–163 parasites per 10 000 erythrocytes). In 12 singly infected and 3 coinfected samples identified using PCR, no parasites were seen under the microscope (10 Plasmodium spp.-infected, 2 Parahaemoproteus spp.-infected and 3 infected with Plasmodium spp. and Parahaemoproteus spp.). Three samples tested negative for Leucocytozoon spp. and 2 tested negative for Parahaemoproteus spp. using PCR, despite parasites being identified on blood smears. Photographs of each parasite genus seen during microscopic examination can be found in Supplementary file 1.

Figure 1. Number of samples (a) singly infected and (b) doubly infected with parasites belonging to each genus/genera combination.

Sequence analysis

We were able to obtain 54 good quality sequences, of which 17 were identified as Plasmodium spp., 32 were Parahaemoproteus spp. and 5 were Leucocytozoon spp. We identified 5 unique Plasmodium spp. sequences, 11 unique Parahaemoproteus spp. sequences, and 4 unique Leucocytozoon spp. sequences (Table 2). Eleven of the 54 sequences were obtained from coinfected samples (1 sample was infected with Plas1, Haem1 and Leuc1 concurrently, 1 with Haem10 and Leuc2, 1 with Haem5 and Plas3, and 2 samples were infected with Plas1 and Haem1).

Table 2. Haemosporidian lineages sequenced from infected samples as part of this study, alongside their closest matches on MalAvi and GenBank

There are no data for Plasmodium and Haemoproteus MalAvi matches as the amplified DNA region does not overlap with the MalAvi region.

Plas1 was isolated from 8 individuals within this study and was identical to sequences of both Plasmodium vaughani collected from a blackbird in Lithuania and Plasmodium unalis collected from a Great thrush (Turdus fuscater) in Colombia (Table 2). Plas2 was isolated from 4 individuals and was a new sequence with 99.67% similarity to 10 sequences, detailed in Table 2. Plas3 was isolated from 2 blackbirds in this study, and was a 97.31% match to 10 sequences on GenBank: Plasmodium juxtanucleare from a short-crested flycatcher (Myiarchus ferox) in Brazil, 2 sequences of P. unalis from Great thrushes in Colombia, P. vaughani from a blackbird in Lithuania, Plasmodium homopolare from a rufous-collared sparrow (Zonotrichia capensis) in Colombia, 3 sequences of Plasmodium gallinaceum from a domestic chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) and Plasmodium sp. from Swainson's thrush (Catharus ustulatus) in Colombia, an African penguin (Spheniscus demersus) in South Africa, and a Northern bobwhite quail (Colinus virginianus ridgwayi) in the USA. Plas4 was found in 2 blackbirds in this study, and was identical to only 1 sequence, Plasmodium circumflexum, isolated from a wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) in Lithuania. We isolated Plas5 from 1 blackbird: this was a new sequence with 99.31% identity to 17 sequences in GenBank, detailed in Table 2.

Haem1, isolated from 19 blackbirds in this study, was identical to 1 sequence on GenBank, Haemoproteus minutus, isolated from a blackbird in Lithuania. Haem2–Haem11 were all new sequences, with 97–99% similarity to the same sequence as Haem 1 (Table 2).

Leuc1, isolated from 2 blackbirds in this study, was identical to TUMER01 at the region of overlap with the MalAvi region (235 bp). This lineage has been reported mostly from blackbirds across western Europe and North Africa, with 1 report from a house sparrow (Passer domesticus) in the Azores. Leuc2, isolated from 1 individual, was identical to both TUMER01 and TUMER07 at the region of overlap; TUMER07 has only previously been reported from a single blackbird in Portugal. Leuc3, also isolated from a single blackbird, may be a new lineage, with 95% match to TUMER19 on MalAvi at the region of overlap: TUMER19 was isolated from a blackbird in Armenia. Leuc4 was a 99% match at the MalAvi region and a 99.23% match on GenBank to lineage COLBF08 isolated from the Woodland Black Fly (Simulium silvestre) in the USA: this lineage had not previously been isolated from an avian host (Table 2).

Impacts of infection

No significant differences in H:L ratio (F 1 = 0.27, P = 0.60) or WBC count (F 1 = 0.78, P = 0.38) were detected between coinfected blackbirds (T. merula) and those that were not coinfected (H:L ratio, coinfected: 0.199 ± 0.017; not coinfected: 0.185 ± 0.011; WBC count, coinfected: 14 806.767 ± 1663.892; not coinfected: 16 823.315 ± 1280.073). Similarly, haemosporidian genus number (0, 1, 2, 3) also had no significant effect on H:L ratio (F 1 = 0.09, P = 0.76; 0:0.190 ± 0.021; 1:0.182 ± 0.013; 2:0.198 ± 0.017; 3:0.210 ± 0.080) or WBC count (F 1 = 1.81, P = 0.15; 0 genera: 22 066.158 ± 3421.956; 1:14 588.661 ± 995.793; 2:15 226.516 ± 1774.760; 3:9489.941 ± 1840.128), although there were significant differences in parasitaemia between individuals infected with 1 genus and those infected with 2 genera (χ22 = 44.34, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). When controlling for coinfection status, parasitaemia had no significant effect on H:L ratio (F 1 = 0.12, P = 0.73) or WBC count (F 1 = 2.20, P = 0.14). This was also true when controlling for genus number (H:L ratio: F 1 = 0.13, P = 0.72; WBC count: F 1 = 1.36, P = 0.25).

Figure 2. Mean number of parasites per 10 000 red blood cells in blackbird (Turdus merula) blood smears infected with 1, 2 or 3 avian haemosporidian genera (singly infected: n = 61; 2 genera: n = 38; 3 genera: n = 3). Error bars represent ±1s.e.

Co-occurrence analysis

At the genus level, associations between genera did not differ from random, given the prevalence of each in the population (P > 0.05 for each association). However, all but 1 Leucocytozoon spp. infection (n = 8) occurred alongside either a Plasmodium spp. or a Haemoproteus spp. infection.

Discussion

A high prevalence of avian haemosporidian infection was found amongst sampled blackbirds (T. merula), as just under 80% were infected with at least 1 genus of parasite. Although we only sampled birds from 1 area of the UK, other studies have reported high levels of haemosporidian infection in passerine birds from other locations across the UK and Europe (e.g. Hatchwell et al., Reference Hatchwell, Wood, Anwar and Perrins2000; Valkiūnas et al., Reference Valkiūnas, Iezhova and Shapoval2003), suggesting that our findings may be reflective of general infection patterns in this species. We found Plasmodium parasites to be the most common of all 3 haemosporidian genera, followed by Haemoproteus spp. and then Leucocytozoon spp., which concurs with the high incidences of Plasmodium spp. reported in blackbirds in various European countries (Dinhopl et al., Reference Dinhopl, Nedorost, Mostegl, Weissenbacher-Lang and Weissenböck2015; Himmel et al., Reference Himmel, Harl, Pfanner, Nedorost, Nowotny and Weissenbock2020).

We identified 5 strains of Plasmodium spp., 11 strains of Haemoproteus spp. and 4 strains of Leucocytozoon spp. in sampled blackbirds. Plas1 matched sequences for P. unalis and P. vaughani. However, as P. unalis has been isolated almost exclusively from birds in America (Harl et al., Reference Harl, Himmel, Valkiūnas, Ilgūnas, Bakonyi and Weissenböck2020), whereas P. vaughani is commonly found in Europe, we expect that our samples were infected with P. vaughani. As Plas2, Plas3 and Plas5 matched with a considerable number of sequences on GenBank, it is difficult to determine the exact identity of these sequences. However, this suggests that the primers PMF and PMR may be useful in the amplification of a wide variety of Plasmodium strains, although further work is needed to determine whether this region may be useful as a barcode for species discrimination. Leuc2 matched with sequences for TUMER01 and TUMER07, although the individual sampled in the present study was more likely infected with TUMER01, given its considerably higher prevalence in this host species.

We also detected a considerable prevalence of haemosporidian coinfection, as 32.03% of all individuals tested positive for infection with at least 2 genera. Similar rates of avian malaria coinfection have been reported in other host species, including a 31% prevalence in American crow nestlings (Townsend et al., Reference Townsend, Wheeler, Freund, Sehgal and Boyce2018). These results may be unsurprising considering the high prevalence and diversity of avian malaria parasites globally, and the observation that birds already infected with either Plasmodium spp., Haemoproteus spp. or Leucocytozoon spp. appear more likely to be subsequently infected with another haemosporidian genus (Norte et al., Reference Norte, Araujo, Sampaio, Sousa and Ramos2009). However, there is substantial variation in reported rates of haemosporidian coinfection, for example, coinfection rates recorded by Starkloff and Galen (Reference Starkloff and Galen2023) ranged from 7 to 75% depending on the host population. This is likely due to the many different factors known to influence haemosporidian infection prevalence in the wild, including host species (Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Hochachka, Engel, Bell, Tkach, Bates, Hackett and Weckstein2015), migratory behaviour (Ciloglu et al., Reference Ciloglu, Ergen, Inci, Dik, Duzlu, Onder, Yetismis, Bensch, Valkiūnas and Yildirim2020), environmental conditions and the abundance and activity of vectors (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Dunn, Dawson, Hipperson, Horsburgh, Morris, Orsman, Mallord, Grice, Hamer and Eraud2022).

Contrary to our hypothesis, we detected no significant differences in H:L ratio or WBC count between uninfected and singly infected individuals, suggesting that infection with 1 haemosporidian genus does not impose significant immune-related costs on hosts. This is supported by several studies, all detecting no effect of parasite presence on immunological parameters such as H:L ratio (Krams et al., Reference Krams, Suraka, Rantala, Sepp, Mierauskas, Vrublevska and Krama2013), haematocrit levels (Bichet et al., Reference Bichet, Brischoux, Ribout, Parenteau, Meillere and Angelier2020) and WBC count (Vanstreels et al., Reference Vanstreels, Dutra, Ferreira-Junior, Hurtado, Egert, Mayorga, Bhering, Braga and Catão-Dias2019). These results could be a consequence of long-term coevolution between haemosporidian parasites and their avian hosts (Norte et al., Reference Norte, Araujo, Sampaio, Sousa and Ramos2009), which can reduce parasite virulence, subsequently evoking weaker immune responses (Macintosh and Frias, Reference Macintosh, Frias and Fuentes2017). These coevolutionary relationships can have severe implications for naïve populations, potentially causing high morbidity and mortality (Garnick, Reference Garnick1992; Woodworth et al., Reference Woodworth, Atkinson, Lapointe, Hart, Spiegel, Tweed, Henneman, LeBrun, Denette, DeMots, Kozar, Triglia, Lease, Gregor, Smith and Duffy2005). As such, further investigation into the dynamics of coevolutionary relationships should be a priority. However, coevolution has not eliminated all the costs that avian malaria parasites impose upon host individuals, as significant immune responses to these parasites, including increased WBC counts and H:L ratios (Wojczulanis-Jakubas et al., Reference Wojczulanis-Jakubas, Jakubas, Czujkowska, Kulaszewicz and Kruszewicz2012; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Goodman, Benton and Hamer2013; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Kunkel and Ricklefs2014, Reference Ellis, Cornet, Merrill, Kunkel, Tsunekage and Ricklefs2015), have been recorded in species that are frequently infected by haemosporidians. This evidences the complexities of host–parasite coevolution and the many different factors that can influence immune responses to parasitic infection.

We also found no effect of coinfection on H:L ratio or WBC count. Similar findings were reported by Palinauskas et al. (Reference Palinauskas, Žiegytė, Šengaut and Bernotienė2018), who found no significant differences in body weight between singly infected domestic canaries (Canaria domestica) and those infected with 2 different Plasmodium species. Likewise, Chavarría et al. (Reference Chavarría, Matta, Cadena-Ortíz, Alarcón, Bahamonde-Vinueza, González and Bonaccorso2023) found no effect of coinfection on body condition or polychromatophil count in the ash-breasted Sierra finch (Geospizopsis plebejus). Conversely, other studies have detected additive costs of coinfection in comparison to single infection, in terms of body condition (Marzal et al., Reference Marzal, Bensch, Reviriego, Balbontin and de Lope2008) and survival probability (Pigeault et al., Reference Pigeault, Cozzarolo, Choquet, Strehler, Jenkins, Delhaye, Bovet, Wassef, Glaizot and Christe2018). The impacts of coinfection on host individuals are dependent on the nature of the interactions occurring between parasites within the host (Karvonen et al., Reference Karvonen, Jokela and Laine2019). If interactions are antagonistic, infection virulence will be lowered in comparison to single infection, due to the suppression of 1 parasite by another (Clay and Rudolf, Reference Clay and Rudolf2019; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Qu, Zhang, Li and Lv2019). Facultative interactions on the other hand, in which both parasites benefit, can impose greater costs on hosts (Clay and Rudolf, Reference Clay and Rudolf2019). To fully understand the reasons for the observed differences in coinfection costs, exploration into the interactions that occur between different haemosporidian parasites within avian hosts is needed.

It would be interesting for future work to test for the impacts of coinfection specific to certain parasite species or lineages. This is because different haemosporidian genera, species and lineages exhibit different life history traits, patterns of development inside the avian host and levels of pathogenicity (Atkinson and Riper, Reference Atkinson, Riper, Loye and Zuk1991; Zehtindjiev et al., Reference Zehtindjiev, Ilieva, Westerdahl, Hansson, Valkiūnas and Bensch2008). For example, Townsend et al. (Reference Townsend, Wheeler, Freund, Sehgal and Boyce2018) found that, of the 3 avian haemosporidian genera, only Plasmodium spp. infection was associated with significant reductions in body condition and haematocrit levels. Additionally, Zehtindjiev et al. (Reference Zehtindjiev, Ilieva, Westerdahl, Hansson, Valkiūnas and Bensch2008) reported lower parasitaemia in great reed warblers (Acrocephalus arundinaceus) infected with Plasmodium relictum compared to individuals infected with Plasmodium ashfordi, and Bentz et al. (Reference Bentz, Rigaud, Barroca, Martin-Laurent, Bru, Moreau and Faivre2006) found that parasitaemia of Plasmodium lineage TM1 was 100–1000× that of Plasmodium TM2 in blackbirds (T. merula). These findings suggest that there may also be differences in the ways in which different parasitic genera, species and lineages interact with each other, and with the host, during coinfection (Rooyen et al., Reference Rooyen, Lalubin, Glaizot and Christe2013). Consequently, the immune-related impacts of parasitic coinfections may be dependent on the identity of the parasites present, meaning our results could obscure significant costs associated with specific combinations of haemosporidian parasites. As such, future research should seek to uncover any potential parasite-specific costs of coinfection.

It is also important to acknowledge the impact that the incorrect diagnosis of infection status may have had on our results, as we recorded infection status based solely on the results of the 1-step multiplex PCR, which appears to have failed to detect infection in a few samples. This study also included blood samples that were diagnosed as infected by PCR, but in which no parasites were seen under the microscope. There are a few possible reasons for such observations, including that these birds were suffering from very light parasitaemia, or that parasite DNA detected during PCR represented parasite remnants that had aborted development (Valkiūnas et al., Reference Valkiūnas, Iezhova, Loisseau and Sehgal2009; Chagas et al., Reference Chagas, Guimarães, Monteiro, Valkiūnas, Katayama, Santos, Guida, Simões and Kirchgatter2016). Consequently, some individuals we recorded as infected might not have been harbouring successful infections. As such, the diagnosis of infection status is probably best achieved using a combination of microscopy and PCR-based techniques.

As well as investigating the immune-related impacts of single infections and coinfections, we also looked at the effect of coinfection on parasitaemia. We found that individuals infected with 2 haemosporidian genera had significantly higher parasitaemia than those infected by 1 genus. As only 3 of our samples were infected with Plasmodium spp., Haemoproteus spp. and Leucocytozoon spp. concurrently, it is possible that this small sample size hampered our ability to also detect a significant influence of 3-genera coinfection on parasitic burden. Other studies have also detected an increase in parasitaemia during coinfections in comparison to single infections (e.g. Palinauskas et al., Reference Palinauskas, Žiegytė, Šengaut and Bernotienė2018; Chavarría et al., Reference Chavarría, Matta, Cadena-Ortíz, Alarcón, Bahamonde-Vinueza, González and Bonaccorso2023), indicating an additive effect of coinfection on parasitaemia (Cox, Reference Cox2001). However, as we did not record the genus of each parasite seen during microscopic examination, we do not have any data on the relative parasitaemia of each genus in coinfected samples. This restricts our ability to comment on potential dynamics that may have been regulating the parasitaemia of each genus. Previous research has detected both positive (Zehtindjiev et al., Reference Zehtindjiev, Ilieva, Westerdahl, Hansson, Valkiūnas and Bensch2008; Palinauskas et al., Reference Palinauskas, Valkiūnas, Bolshakov and Bensch2011) and negative relationships (Palinauskas et al., Reference Palinauskas, Valkiūnas, Bolshakov and Bensch2011) between the parasitaemia of different coinfecting haemosporidians, as well as significant variation in parasitaemia dynamics across coinfected host species. As there is much research demonstrating the significant influence that haemosporidian parasitaemia has on infection costs (e.g. Sol et al., Reference Sol, Jovani and Torres2003; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Cornet, Merrill, Kunkel, Tsunekage and Ricklefs2015), it is important that the mechanisms that regulate these observed dynamics are investigated further and any changes in these dynamics over the course of infection are recorded.

Contrary to the aforementioned research, we found that parasitaemia had no influence on H:L ratio or WBC count. This could be explained by the generally low levels of parasitic burden detected amongst sampled individuals, suggesting that most birds were suffering from chronic rather than acute infection. As the acute phase of haemosporidian infection imposes greater costs on avian hosts than chronic infection (Krams et al., Reference Krams, Suraka, Rantala, Sepp, Mierauskas, Vrublevska and Krama2013), it is possible that this prevented us from detecting an effect of parasitaemia and infection status on immune activity. Unfortunately, it is more difficult to collect samples from wild birds experiencing acute infection, as these individuals are more likely to reduce their levels of activity and may die before being sampled (Yorinks and Atkinson, Reference Yorinks and Atkinson2000; Krams et al., Reference Krams, Suraka, Rantala, Sepp, Mierauskas, Vrublevska and Krama2013). On the other hand, studies that have used anti-Haemosporidia medications to treat chronic infections have uncovered associations between chronic infection and reduced host survival and reproductive success (Knowles et al., Reference Knowles, Palinauskas and Sheldon2010; Martínez-de la Puente et al., Reference Martínez-de la Puente, Merino, Tomás, Moreno, Morales, Lobato, Garcia-Fraile and Belda2010). This suggests that even low parasitic burdens can exert significant costs in some circumstances. However, the impacts of haemosporidian infections on wild hosts are dependent on a variety of factors aside from parasitaemia, including food availability and environmental conditions. For example, Cornet et al. (Reference Cornet, Bichet, Larcombe, Faivre and Sorci2014) found that nutritionally supplemented domestic canaries (Serinus canaria) were better able to control Plasmodium relictum burdens than those that were not supplemented. It is difficult to assess the extent to which these factors influenced the results of this study, as with any study of haemosporidian infection costs conducted on wild birds. Further examination of the effect of these variables in controlled conditions may help to shed more light on their possible effects in wild environments.

In conclusion, we detected high rates of haemosporidian infection and coinfection, but found no evidence that either impacted immune activity, despite a significantly higher parasitic burden in individuals experiencing double vs single infection. This could be a result of coevolution, which has reduced parasite virulence, or a reflection of the reduced costs associated with chronic infection in comparison to acute infection. These findings may obscure significant impacts associated with specific combinations of coinfecting haemosporidian genera, species or lineages. Further research into the interactions that occur between parasites within the host, and how these interactions and resulting impacts may vary depending on parasite identity, would help to facilitate a better understanding of the costs of coinfection in this system.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182024000829.

Data availability statement

Sequences generated in this research are accessible through GenBank accession numbers PP850198–PP850217.

Acknowledgements

Sample collection was partly funded by Royal Society Research grant RG170086 to J. C. D., and laboratory analysis was funded through E. L.'s MBio research project at the University of Lincoln. Blood samples were collected under licence from the UK Home Office, and birds were caught under licence from the British Trust for Ornithology.

Author contributions

E. L. designed the study, conducted laboratory analysis, performed statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. J. C. D. conceived the study, provided pre-collected samples and edited the manuscript.

Financial support

Sample collection was partly funded by Royal Society Research grant RG170086 to J. C. D., and laboratory analysis was funded through E. L.'s MBio research project at the University of Lincoln.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

All blood samples were collected under licence from the UK Home Office. This work was approved by both the University of Leeds Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Committee, and the University of Lincoln Animal Ethics Committee.