Social protest is uncommon in closed autocracies. But protest is a daily practice in partially open authoritarian regimes in which incumbents seek to prevent coups or revolutions through limited power-sharing agreements. When autocrats consent to government-controlled multiparty elections—the most common type of power-sharing agreement in the authoritarian world today—they simultaneously activate the ballot and the street. Whereas in closed autocracies like China or Cuba we only see episodic and isolated acts of local protest for the satisfaction of particularistic demands, in electoral autocracies we often see the outbreak of major cycles of national protest in which a wide variety of social activists, groups and movements, and opposition parties transcend their particularistic claims and mobilize for larger political goals, particularly the goal of democratization.

Why does the introduction of multiparty elections in autocracies stimulate the rise of major cycles of protest? Why does the activation of the ballot politicize the street and why does the introduction of multiparty elections give rise to socio-electoral coalitions between opposition parties and social movements? When do authoritarian elections become an important mechanism for the spatial and temporal aggregation of local and isolated protest events into major waves of political mobilization?

The connection between the ballot and the street is theoretically puzzling because the objectives and strategies of political parties and social movements often come into conflict. As Doug McAdam and Sidney Tarrow have insightfully observed, there is an “inherent tension between the logic of movement activism and the logic of electoral politics.” Footnote 1 While political parties in democracies are compelled to build cross-class and pluralistic coalitions that appeal to the greatest number of voters, social movements develop radical commitments toward single issues for which they fight in the streets. Establishing an electoral coalition with militant social movements can compromise a party’s ability to win electoral majorities. But entering electoral politics compels a social movement to compromise its demands, identities, and independence and can jeopardize the movement’s own existence. Footnote 2

Understanding the logic of the street in autocracies is important because social protest is one of the few mechanisms of policy negotiation for independent citizens and groups. But understanding the process of aggregation of isolated movements and protest events into major cycles of mobilization is theoretically and politically crucial because these waves of protest can be precursors of the democratization of authoritarian regimes Footnote 3 or of the outbreak of armed insurgencies and civil war. Footnote 4

Building on neo-institutional theories of authoritarian regimes Footnote 5 and on theories of collective action and social movements, Footnote 6 I develop a theory of social protest in autocracies that seeks to explain why electoral incentives associated with the introduction of partially free and unfair elections can give rise to a strategic partnership between opposition parties and social movements and how this contingent association can contribute to the spatial aggregation of isolated protest events into major episodes of mobilization. Unlike some of the most influential studies of protest in autocracies, which focus almost exclusively on post-electoral protest, Footnote 7 my account also explains the inter-temporal aggregation of protest episodes taking place in election and non-election times and the formation of major cycles of mobilization in which protest is more intense during election cycles but persists beyond elections.

The electoral theory of social protest is built on a basic premise: when autocrats introduce partially free and unfair multiparty elections, opposition parties are forced to compete for office while at the same time contesting the rules of electoral competition. Opposition parties play a two-level game: at the micro level, they have to win votes but at the macro level they have to transform the rules that prevent them from winning electoral majorities. Footnote 8

The theory’s most basic proposition is that to play this nested game, opposition parties have powerful incentives to recruit social movements to help them build a core electoral constituency and lead popular mobilization during election campaigns and in post-election rallies to contest fraud. Because electoral participation can be a major source of internal divisions for social movements, social leaders and activists will take to the streets to help parties fulfill their electoral goals when opposition party leaders become major sponsors of their causes and provide them with important financial and logistic resources and institutional protection to continue mobilizing during non-election times. This quid pro quo between social movements and opposition parties gives rise to socio-electoral coalitions and facilitates the spatial and temporal aggregation of isolated events of local protest into major cycles of mobilization.

The theory further suggests that when authoritarian elections become increasingly free and fair and when opposition parties become major power contenders, the prospect of electoral victory motivates opposition party leaders to adopt new electoral strategies—to build broad pluralistic coalitions and discourage their social-movement partners from radical mobilization. The democratization of elections and opposition electoral victories allow opposition parties to offer social leaders and activists patronage resources or the implementation of the movement’s policy demands in exchange for the de-radicalization and partial de-mobilization of the street.

An important observable implication of the electoral theory of social protest is the existence of socio-electoral cycles in electoral autocracies—heightened protest during elections. Although social movements take to the streets for a wide variety of causes and at different time periods, election cycles are associated with the highest peaks of protest. Elections are a magnet of protest because mass demonstrations are one of the most effective means for opposition parties to prosper in the two-level game of authoritarian elections. Because authoritarian incumbents tend to be more vulnerable during elections, election cycles are also an ideal time for social movements to achieve their policy aims in the streets, particularly when national and subnational authorities are elected concurrently.

I test these propositions and observable implications using quantitative and qualitative data from a powerful cycle of rural indigenous protest that took place in Mexico as the country transitioned from de facto one-party autocracy to multiparty autocracy (1977) and then into multiparty democracy (2000). Based on information from the Mexican Indigenous Insurgency Database (MII)—an original dataset of 3,553 protest events that took place in Mexico’s 883 indigenous municipalities between 1975 and 2000—and on case studies, I assess whether the introduction of government-controlled multiparty elections and the uneven spread of electoral competition across indigenous municipalities had any impact on the rise, development, and demise of the country’s powerful cycle of indigenous protest.

Focusing on Mexico’s cycle of indigenous protest for hypothesis testing allows us to isolate the impact of elections on protest because the introduction of government-controlled multiparty elections in 1977 was exogenous to the indigenous world. After years of fighting urban and rural guerrilla movements, in which indigenous communities were not involved, authoritarian elites consented to legalize all political parties and allow the selection of public authorities through partially-free and unfair elections.

Focusing on rural indigenous protest provides us with a unique opportunity to avoid the urban bias prevalent in studies of protest in autocracies, in which authors typically focus on mass mobilization taking place in the countries’ predominantly urban capitals. Relegated to the rural periphery of Mexican states, living in mountainous terrain or in rainforests where government presence is low and institutions weak, indigenous communities represent a “least-likely case”: if electoral incentives do have an impact on protest in these remote and weakly institutionalized places and contribute to aggregate isolated protest events into major cycles of mobilization, then we can confidently expect that elections will shape protest in urban areas as well.

Using information from the MII Database—which contains data from eight Mexican national daily newspapers—provides us with systematic information about protest events taking place during election and non-election times from 1975 to 2000. Footnote 9 The use of time series of protest allows me to overcome the implicit bias in most studies of protest in autocracies that narrowly focus on post-election protest in stolen elections and hence conceive protest as a one-shot game.

I will first discuss alternative explanations of protest in autocracies, outline the electoral theory of protest, and present the article’s central theoretical propositions. Next I present statistical tests and case studies based on micro data of indigenous protest in Mexico and in the fourth section I show that electoral incentives for social protest have shaped cycles of mobilization in a wide range of cases beyond Mexico, including Guatemala, El Salvador, Brazil, the Philippines, and Algeria. The concluding section discusses how a focus on the incentive system that enables the development of opposition socio-electoral coalitions—such as the one proposed here—can improve our understanding of cycles of protest in autocracies and the impact of protest on dynamics of stability and change of authoritarian regimes. Footnote 10

Neo-Institutional Theories of Autocracies and the Study of Social Protest

Drawing on the experience of absolutist and totalitarian regimes, for a long time scholars of authoritarianism argued that the systematic and consistent use of lethal repression rendered dissident collective action nearly impossible in autocracies. A few suggested that social networks and underground action facilitated episodic protest events. Footnote 11 But the most influential accounts suggested that it was only when rulers signaled their inability to consistently repress dissent that the defiant actions of a few individuals in the streets gave rise to cascades of participation and the demise of authoritarian regimes. Footnote 12

The development of neo-institutional theories of autocracies in recent years has stimulated a major reassessment of the logic of governance in authoritarian regimes. Three findings are particularly important.

First, the family of authoritarian regimes is larger than the totalitarian/authoritarian distinction that guided most scholarship during the latter part of the twentieth century. It comprises a wide range of regime types, including 1) monarchic, 2) military, 3) single-party, 4) multi-party, and 5) personalistic regimes. Combinations of key elements of these five basic authoritarian types have given rise to a number of hybrid authoritarian regimes. Footnote 13

Second, when autocrats face major challenges from members of their own coalition or from below, they do not always brutally repress them; authoritarian incumbents often introduce limited power-sharing agreements to stay in power. Footnote 14 They build legislatures, subnational governments, and political parties, and consent to government-controlled elections. Footnote 15 Most authoritarian regimes in the world today allow citizens to select their leaders through partially free and unfair elections. Footnote 16

Finally, most regime transitions do not entail direct shifts from autocracy to democracy but rather partial processes of incremental liberalization from one type of authoritarian regime to another. Footnote 17 Authoritarian liberalization typically involves the limited expansion of electoral competition. The literature shows that after several rounds of political liberalization, it is competitive multiparty autocracies—not hegemonic-party autocracies—that are more likely to be transformed into electoral democracies. Footnote 18

These findings reveal the Janus-faced nature of authoritarian elections: they can be an important tool of authoritarian governance – one of the most effective instruments available to authoritarian incumbents to institutionalize conflict without altogether surrendering power – or an important mechanism for the democratization of authoritarian controls.

This important reassessment of authoritarian governance has led us to rethink the logic of collective action in autocracies.

Whereas traditional studies assumed that authoritarian incumbents would systematically oppose any form of independent collective action, neo-institutional studies suggest that autocrats may actually have meaningful incentives to tolerate limited forms of protest. Public demonstrations provide incumbents with invaluable information about regime challengers and about the performance of subnational elites. Footnote 19 As Graeme Robertson aptly summarizes this point, Footnote 20 the autocrat’s challenge is not to eliminate all forms of protest but to “manage” dissent and to prevent it from becoming a revolutionary challenge.

Whereas traditional studies assumed that protest would be nearly impossible in autocracies, the neo-institutional literature has shown that fraudulent elections can be a focal point for mass protest. Footnote 21 Focusing on the Color Revolutions in Eastern Europe, two influential accounts explain the rise of major cycles of electoral protest that resulted in the removal of authoritarian leaders.

Joshua Tucker Footnote 22 and Philipp Kuntz and Mark Thompson Footnote 23 independently argue that stolen elections are transformative events that offer large numbers of unorganized citizens an unusual opportunity to spontaneously express their “grievances” or “moral outrage” against the regime in the streets. Taking to the streets in the aftermath of a major election fraud is less dangerous than at other times and can be rewarding for citizens because authoritarian incumbents are vulnerable and unable to effectively repress dissent and the probability of success in removing leaders is actually high.

Mark Beissinger Footnote 24 and Valerie Bunce and Sharon Wolchik Footnote 25 independently argue that powerful coalitions of social movements, NGOs and opposition parties played a major role in mobilizing opposition voters to go to the polls, overseeing election procedures, and denouncing fraud in post-election mass mobilizations in pivotal national elections in which incumbents stole opposition victories. In this influential account, organizational strategy, rather than spontaneous action, was a sine qua non for the successful mass mobilization of opposition forces and for the removal of authoritarian leaders.

The neo-institutional literature has made important progress by showing that authoritarian elites may face incentives to tolerate limited forms of protest, but it has also shown that there are limits to their ability to control society from above. When they resort to blatant electoral fraud to stay in power, autocrats can lose control of the streets.

Despite substantial intellectual progress, neo-institutional explanations of protest in autocracies face significant limitations because they have narrowly focused on government and opposition party elites and have little to say about the motivations that lead social movements to respond to opportunities that elites open from above. If authoritarian elites permit limited forms of protest in order to legitimize the regime and obtain information about anti-regime challengers, it is unclear why social movements would take to the streets and play this game in the first place. If opposition parties try to recruit social movements to play the dual game of authoritarian elections, it is unclear why social movements would support opposition party elites, when establishing an electoral coalition with opposition parties could compromise the movements’ objectives and integrity.

The literature has avoided these questions because some scholars have assumed that (post-election) protest is unorganized and spontaneous and hence social movements play no significant role in mobilizing the street. And those who see social movements playing a crucial organizational role in pre- and post-electoral mobilizations have made the strong assumption that social movements take to the streets because they are proto-democratic actors.

An additional limitation is that a narrow focus on post-electoral protest in stolen elections has led the literature to neglect the study of protest in non-election times and to ignore the important inter-temporal connections between electoral and non-electoral protests. This bias has prevented the literature from fully recognizing the existence of broader cycles of mobilization in electoral autocracies in which protest tends to be more intense around elections but persists beyond election cycles.

To overcome these shortcomings we need to expand our current theorizing by exploring how the introduction of government-controlled multiparty elections in autocracies transforms the incentives and behavior of both social movements and political parties, facilitating the connection between the ballot and the street.

An Electoral Theory of Social Protest in Autocracies

When autocrats face major threats of coups or revolutions they can leave office, fight back and brutally repress their opponents, or introduce power-sharing agreements. Power sharing may range from minor political liberalization to full-blown democratization. Autocrats offer power-sharing agreements when they are unsure about their ability to completely eliminate opposition challengers and when they expect to remain as a major player under a new partially-liberalized regime. Dissidents accept limited power-sharing agreements when they are unsure about their ability to remove the government by force and when they expect to eventually win office under the new regime. Footnote 26

Assume a situation in which autocrats adopt government-controlled multiparty elections to combat a major challenge from below. Although the introduction of government-controlled elections makes opposition parties the most visible opposition actor and the electoral arena the most important site for political negotiation, parties are not the only relevant opposition actor and elections are not the only relevant political arena. Figure 1 shows three of the most important groups that have historically constituted the opposition in electoral autocracies: armed rebel groups, social movements, and political parties. These groups pursue different goals, adopt different means of action, and operate in different arenas. Footnote 27

Figure 1 Opposition groups in electoral autocracies

Armed rebel groups and opposition parties are organizations that seek political power but differ in their means of action. Whereas armed rebel groups operate underground and train their members professionally in the use of force with a view to the removal of authoritarian incumbents, opposition parties seek power through non-violent means and run political campaigns to unseat authoritarian incumbents through elections.

Social movements are networks of activists and organized groups that seek government concessions in specific policy areas through peaceful public demonstrations. For example, peasant movements seek land redistribution; squatter movements demand housing, sanitation, and urban development; and student movements fight for education subsidies. Although movements’ goals can change and are endogenous to mobilization, I assume that their initial goal of transforming policy rather than political regimes distinguishes them from both opposition parties and armed rebel groups.

As figure 1 suggests, social movements are the pivotal opposition actor. They can serve as the social base for revolutionary coalitions when rebel groups try to remove governments through guerrilla warfare. But they can also become the social base for electoral coalitions when opposition parties seek to unseat incumbents through elections. These are not static but dynamic relationships in which armed rebel groups and opposition parties permanently compete to recruit social movements into their cause. Footnote 28

The state plays a key role in determining which coalition prevails. By introducing power-sharing agreements, authoritarian incumbents seek to isolate armed rebel groups. By legalizing opposition parties and consenting to government-controlled elections, autocrats activate elections as the main arena for political contestation and empower opposition parties to attract social movements into the electoral realm. Their new challenge will be to “manage” opposition growth by keeping social activists away from opposition parties through selective incentives and targeted repression.

Despite the incumbent’s attempts to thwart the alliance between the ballot and the street, the introduction of partially free and unfair elections introduces powerful incentives for movements and parties to overcome their strategic differences and to work together. How they do it and how these socio-electoral coalitions shape dynamics of protest are the critical theoretical questions.

Socio-electoral Coalitions and the Rise and Demise of Cycles of Protest

Elections in electoral autocracies are neither entirely free nor completely fair. Although authoritarian incumbents do not exclude opposition parties from competition or preclude voters from participating in elections, they enjoy unique access to patronage resources and control the state’s means of coercion and the media and the institutions that organize elections. These privileges enable them to engage in vote buying and coercion and to single-handedly alter electoral outcomes. Footnote 29

The way elections in autocracies are institutionalized has crucial consequences for protest. As Andreas Schedler and Scott Mainwaring have independently pointed out, elections in autocracies are two-level games: opposition parties are compelled to compete for office while simultaneously contesting the rules of competition. Footnote 30 In the language of Mainwaring, opposition parties play an “electoral game” by which they seek to maximize votes and a “regime game” by which they seek to transform political institutions. This dual goal shapes opposition party behavior in fundamental ways—it conditions their electoral platforms, coalition partners, and participation strategies.

To simultaneously fight fraud and build a core electoral constituency, opposition parties do not initially appeal to moderate voters but seek instead to recruit social leaders and activists from marginalized and excluded independent groups and movements. Any group that claims policy concessions outside established authoritarian channels is considered to be independent. Groups are marginalized when they embrace policy positions that the government considers “extremist”—e.g., peasant movements demanding land redistribution from a military regime supported by landowners or environmentalists in regimes that support industrialization. Groups are excluded when their main policy goals cannot be mapped onto the main political dimensions of authoritarian politics—e.g., religious groups in secular autocracies or groups demanding sexual liberation in conservative autocracies.

Opposition parties actively seek to recruit leaders and activists from marginalized and excluded groups and movements because these are risk-acceptant individuals with strong policy preferences on specific issues, long-term outlooks, and access to extensive social networks. They are individuals capable of discounting the risks of voting for an opposition party and waiting for their goals to be fulfilled; Footnote 31 mobilizing their group members and filling up the public plazas during election campaigns; canvassing, mobilizing voters, overseeing election procedures on voting day; and leading major post-election protests to contest fraud. Footnote 32

While recruiting social movements empowers opposition parties to play the two-level game of autocratic elections, entering the electoral arena poses important challenges for social movements. Because opposition party building and electoral success depend on a continual search for new allies, participating in elections requires that movements compromise some of their core demands and identities. Footnote 33 For radical social activists, “softening” group demands and identities means “selling out” their movement.

To help social movement leaders minimize the potential costs of electoral participation, opposition parties can take bold action to show that socio-electoral coalitions can contribute to achieve the movement’s policy goals. Besides the promise of future implementation of the movement’s policy agenda and access to patronage for leaders and activists, opposition parties can provide significant financial and logistic resources for group mobilization during non-election times. When opposition candidates win positions in national or state legislatures or when they win subnational executive office, they can become important institutional voices for publicizing their allies’ demands and denouncing violations of the human rights of social movement members. These actions can be a powerful signal of a party’s credible commitment toward their social allies and contribute to materializing socio-electoral coalitions.

Socio-electoral coalitions are strategic alliances between social movements and opposition parties that come into existence only when movements and parties can credibly show their members that an alliance between the ballot and the street will serve each group to fulfill their long-term goals. Because the goals of movements and parties often come into conflict, the development of socio-electoral coalitions requires that parties and movements undergo significant changes.

After the introduction of government-controlled elections, opposition parties often become umbrella organizations for a plurality of niche causes Footnote 34 and their platforms become manifestos of contradictory policies that reflect the wide variety of social groups and movements that have become members of their electoral coalition. The initial appeal to marginalized and excluded groups and the support for direct political action in the streets transforms opposition parties into movement parties.

Social movements, in turn, rapidly become politicized. Although they initially make group-specific demands for land, housing, paved roads, education subsidies, environmental protections, religious liberty, or ethnic autonomy, participation in socio-electoral coalitions often transforms their particularistic demands into more universal claims for free and fair elections. This struggle galvanizes a wide variety of movements into a socio-electoral front for democratization.

The successful development of opposition socio-electoral coalitions can give rise to major cycles of protest, that is, extensive periods of social mobilization in which a multiplicity of actors and groups with different interests and from diverse geographic regions transcend their particularistic demands and engage in sustained collective action, united under a master framework, and in the pursuit of larger transformational goals. Footnote 35

In summary, we would expect that:

H.1.a. The introduction of government-controlled multiparty elections in autocracies and the initial spread of electoral competition will stimulate the rise of cycles of peaceful social protest. But the absence of multiparty elections or a weak presence of opposition parties will prevent the aggregation of isolated protest events into cycles of mobilization.

As opposition parties succeed in becoming viable electoral forces and in making fraud increasingly unlikely, the socio-electoral strategies that allowed them to compete while contesting the rules of competition are likely to become a strategic liability. When electoral victories become a possibility, opposition parties are faced with incentives to downplay their initial support for marginalized and radical causes and to begin the construction of moderate policy platforms that will appeal to the median voter. They will encourage social movement leaders and activists to moderate their claims, minimize the use of protest, and become part of broader cross-class and pluralistic electoral coalitions. Footnote 36

Greater access to patronage resources through subnational governments and legislative office allows opposition parties to vertically integrate social movement leaders and activists as local officials. Footnote 37 To the extent that social leaders and activists become party or government officials and concessions trickle down to social movement members, street protest is likely to slowly fade and democratization to become a major force for the demobilization of protest. Footnote 38 We would expect that:

H.1.b. As elections become increasingly free and fair and opposition parties become major electoral contenders, the spread of electoral competition and opposition victories will contribute to the demise of cycles of protest. Footnote 39

Election Cycles as Focal Points for Protest

Election cycles in electoral autocracies represent a unique opportunity for social movements and opposition parties to fulfill their goals in the streets. I distinguish three stages within election cycles: election campaigns, election day, and post-election negotiations. These are long processes that can take up to three-quarters of a year.

For social movements, election cycles are an ideal time to publicize their grievances and demands and become agenda setters. Footnote 40 Because elections attract domestic and international media attention, social movements have powerful incentives to take their claims to the streets during election campaigns. A well-orchestrated demonstration can take a movement to the front pages of national or even international newspapers.

Election cycles produce elite fragmentation and social movements can find new institutional allies with powerful motivations to embrace their cause and provide them with resources to take their claims to the streets. Footnote 41 Because opposition parties are unusually receptive to any publicly available evidence that may erode support for the incumbent party, opposition leaders are likely to echo social movements’ claims and sponsor their mobilization efforts during election campaigns.

Finally, election cycles increase the costs of repression for incumbents Footnote 42 and the probability of concessions for independent social movements. Autocrats tend to follow expansionary fiscal policies and are more prone to concede—rather than repress—during election cycles. Footnote 43 Repression during elections is costly because it can expose incumbents as illegitimate. Although autocrats can disregard election results, they have motivation to win the voters over and remain in power through the use of patronage and clientelism and through moderate and less visible forms of coercion. Footnote 44 Harshly repressive actions during elections could revive threats of revolution.

For opposition parties, major mobilizations during electoral campaigns can be an effective strategy for portraying the opposition as a mass movement. In a context in which voters are uncertain about how many fellow citizens will support the opposition, a mass showing in the streets can help opposition parties create an image of popularity that may stimulate independent and undecided voters to join cascades of opposition participation.

Major mobilizations during campaigns can also signal the opposition’s capacity to engage in post-election mobilization and thus be a deterrent of electoral fraud. Footnote 45 It is an investment that opposition parties make to prevent fraud at a time when the costs of repression are relatively high for incumbents.

Finally, major post-electoral mobilizations can lead to electoral reforms, Footnote 46 policy concessions in non-electoral arenas, or the removal of authoritarian leaders. Footnote 47 As Joshua Tucker persuasively argues, blatant electoral fraud can become a focal point that encourages a wide variety of social and political actors to engage in coordinated mass action in the streets. Footnote 48 Post-election mobilizations are not, however, spontaneous; they are carefully planned events in which leaders and activists of prevailing socio-electoral coalitions play a crucial organizational role. Footnote 49

Given the benefits the street can yield for opposition parties and social movements in electoral autocracies, we would expect that:

H.2.a. Protest intensifies during elections.

Elections in authoritarian regimes often involve the selection of national and subnational authorities. Presidents often have a majority in legislative chambers and the incumbent party controls most subnational governments. These controls enable presidents to be the chief decision-making authority. The de facto political power of executives turns presidential elections into periods of intra-elite division and conflict. Hence, we would expect that:

H.2.b. National elections for executive power should attract more protest than subnational executive elections.

Electoral calendars are crucial for authoritarian governance. Whether national and subnational elections are concurrent or non-concurrent has important implications for authoritarian control. While in centralized systems presidents have incentives to run concurrent elections and seek to shape subnational politics through presidential coattail effects, in less centralized systems subnational elites try to keep their own electoral calendars independent from the center. But subnational electoral calendars may be mixed: subnational elections may be concurrent with national elections in some regions, but staggered in others. When national and subnational elections for executive positions are concurrent, the political stakes are higher, the payoffs for mobilization greater, and opposition parties and movements can more easily coordinate their actions at the center and in the periphery. We would expect that:

H.2.c. Subnational jurisdictions in which state elections are concurrent with national elections should experience more intense levels of protest than those with staggered elections.

Empirical Testing

In this section I put to test the main propositions of the electoral theory of social protest using data from three decades of rural indigenous protest in Mexico. I first discuss statistical tests of the likely impact of electoral competition and election cycles on the intensity of protest and then use micro-historical evidence to show how a socio-electoral coalition between indigenous movements and leftist parties shaped the rise and demise of a powerful cycle of rural indigenous protest.

Mexico’s Cycle of Rural Indigenous Protest

Like other countries in Latin America, Mexico experienced a powerful cycle of indigenous protest in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Footnote 50 This cycle took place as the country transitioned from a de facto one-party autocracy to multiparty electoral autocracy (1977) to democracy (between 1997 and 2000) and from a state-led to a market economy. Footnote 51

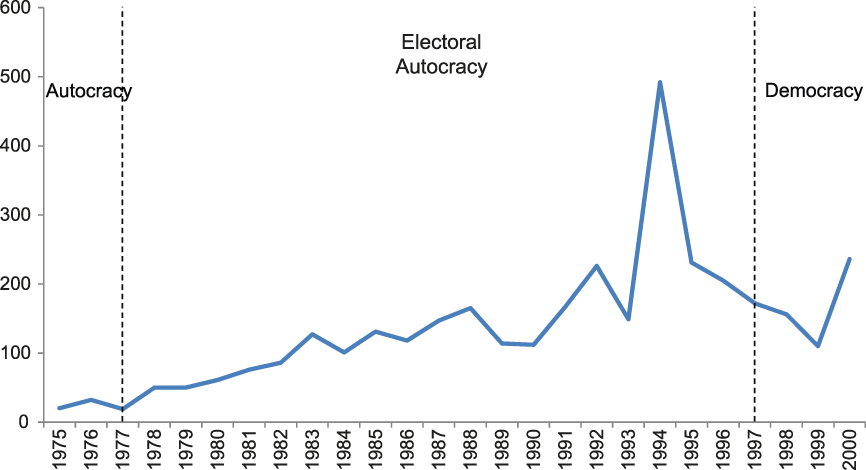

Figure 2A shows a visual illustration of Mexico’s cycle of indigenous protest from 1975 to 2000. It shows 3,553 acts of protest that took place in any Mexican municipality with 10 percent indigenous population (the national mean). The time series of protest includes a wide repertoire of actions, including public petitions, marches, sit-ins, road blockades, land seizures, and occupation of government buildings.

Figure 2A Political regimes and indigenous protest in Mexico

Source: Mexican Indigenous Insurgency Dataset (MII).

Figure 2B Cycles of presidential elections and indigenous protest Mexico

Note: Arrows identify presidential election years.

Sixty percent of protest events were led by more than five hundred different rural indigenous local organizations. Protest actions involved an average of 200 participants who traveled from remote villages in the highlands and lowlands to express their grievances in the streets of their states’ capital cities and occasionally in Mexico City.

While a majority of demands initially involved claims for land redistribution (57 percent), shortly after the introduction of government-controlled multiparty elections in 1977 demands for human rights respect and free and fair elections became dominant for the remainder of the cycle (70 percent). Ethnic claims for autonomy and self-determination only became prominent in the 1990s (30 percent), and even then never displaced demands for free and fair elections as the dominant indigenous claim. Footnote 52

Figure 2A shows that the evolution of Mexico’s cycle of indigenous protest was closely associated with the transformation of political regimes and the expansion of electoral competition—protest took off after Mexico transitioned from one-party to multiparty autocracy and slowly came to an end as the country transitioned into democracy. While figure 2B shows that protest became more intense in years of presidential elections, particularly after elections became truly contested in the 1988, 1994, and 2000 election cycles, Footnote 53 it also shows that protest persisted beyond elections.

Electoral Competition and Indigenous Protest

Beyond the visual evidence, we need a more systematic statistical analysis to confirm or reject the existence of a strong association between the ballot and the street. For purposes of statistical testing, the intensity of indigenous protest in municipality i in year t is the dependent variable. Note that I do not use the raw count of protest as an indicator of intensity but the protesters’ municipal place of origin. For example, if an indigenous protest event took place in the city of Juchitán, in which participants were from Juchitán and three other municipalities, I assign a protest event to each of the four municipalities represented in the event. Because Mexican newspapers do not provide systematic information about number of participants per protest event, this is a reasonable way to measure levels of participation. Under this criterion, the total number of protest events increases from 3,553 to 5,570.

I test for the effect of electoral competition on the intensity of indigenous protest using information on municipal elections. The municipality is an appropriate unit of analysis because socio-electoral coalitions between social movement leaders and activists and opposition parties are usually built at the local level, where social and electoral mobilization actually takes place.

I use the Laakso–Taagepera index of the effective number of parties (ENP) as an indicator of electoral competition. ENP is defined as 1/∑pi 2, where pi represents the proportion of a municipal adult population that adheres to party i as reported by election results in the Banamex (2000), CIDAC (2000), and Remes (Reference Remes2000) data bases. Footnote 54 Because H.1.b suggests the existence of a curvilinear relationship, I test for ENP and ENP2.

The mean ENP is 1.43 and the standard deviation 0.588. Levels of competition changed across decades. The mean ENP was 1.1 in the 1970s (one-party monopoly), 1.7 in the 1990s (semi-competitive elections), and by the end of the 1990s 40 percent of the country’s indigenous municipalities were competitive (ENP > 1.7).

An important feature of electoral competition in Mexican indigenous regions is that until the mid-1990s leftist parties were the only effective opposition. Footnote 55 The PAN, Mexico’s right-wing party, made significant inroads into indigenous regions only in the late 1990s. Hence, for the time period under analysis ENP is an indicator of electoral competition between the ruling party—the PRI—and leftist parties.

To test for the impact of electoral calendars on indigenous protest, I use dummy variables for years of presidential, gubernatorial, and municipal elections. Presidential and gubernatorial elections take place every six years and municipal elections every three years. Election calendars in Mexico are mixed: national, state, and municipal elections are concurrent in some cases but not in others. I first test for the individual effect of presidential, gubernatorial, and municipal elections on indigenous protest and then assess the impact of concurrent presidential and gubernatorial elections on protest.

Although elections may be an important determinant of protest, other factors besides political opportunities affect its intensity. Footnote 56 Exogenous shocks—such as major economic crises or major policy shifts—usually provide the initial impetus for protest. Whether protest intensifies or not depends on the availability of mobilizing vehicles for collective action and on government repression.

I control for the effect of exogenous shocks by introducing dummy variables for years of major macroeconomic crises (1976, 1982, 1985, 1986, 1987, and 1995) and dummies to identify the years in which major economic policy shifts in trade and agricultural policies were enacted. Footnote 57 These were 1984, when Mexico joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT); 1992, when the country liberalized land tenure; and 1994, when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect.

Following one strand in the literature on indigenous mobilization in Latin America, which claims that the Catholic Church contributed to developing the social networks for rural indigenous protest in response to the spread of US Protestant competition, Footnote 58 I control for religious competition using the effective number of religions (ENR) per municipality. Following an alternative view, which claims that rural corporatist unions provided the organizational basis for indigenous collective action, Footnote 59 I control for the municipal level of rural corporatism, which I measure as the interaction between voter turnout and PRI vote share in municipal elections. Rural corporatist organizations affiliated with the PRI were clientelistic networks whose members received economic support in exchange for their mobilization during PRI campaigns and their vote for the ruling party.

I include a count of government repression from the MII dataset and a series of additional controls including poverty, the proportion of indigenous population (to control for the municipal ethnic composition), the log of indigenous population (to control for municipal population size), a one-year lag of protest, and a dummy for southern states (Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero), which are states that have a high concentration of indigenous population and a tradition of poverty, inequality, discrimination, repression, and violent social and political interactions. Footnote 60

I use negative binomial models for statistical testing. Because some of the key explanatory variables and the demographic controls change over time only very slowly, I rely on random effects (RE) rather than fixed effects (FE) models. Note, however, that there are no significant differences between RE and FE models (FE are not shown). I transform coefficients into incidence rate ratios (IRR) to facilitate substantive interpretation.

The results presented in table 1 show that the introduction of government-controlled elections and the uneven spread of multiparty competition across Mexican indigenous municipalities had a large impact on protest.

Table 1 Electoral competition and indigenous protest in Mexico, 1975–2000 (random effects negative binomial models)

* p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. Standard errors in parentheses. One-year lag of Protest and South not shown. IRR = incidence rate ratio.

Consistent with theoretical expectations, Model 1 shows that electoral competition had a strong initial effect on the intensity of indigenous protest (H.1.a). Starting from a base of pure PRI hegemony (ENP = 1), a one-unit increase in the effective number of parties would increase protest by 76 percent. Footnote 61 Because the relationship between electoral competition and protest is curvilinear (H.1.b), Model 1 shows that the initial positive effect of electoral competition on protest grows at decreasing rates until it reaches a maximum at 2.4 effective parties, when opposition parties had established themselves as viable power contenders, and then declines. Footnote 62 If we fix the level of ENP at 2.4, a one-unit increase in ENP would decrease protest by 25 percent.

Mexican electoral history shows that although the PRI introduced government-controlled multiparty elections in 1977, it was not until 1988—when prominent PRI members deserted the ruling party and joined the Left—that opposition candidates became a major electoral force in national and subnational elections. I use 1988 as a cut-off point to split the sample and test for the impact of levels of electoral competition on the intensity of indigenous protest in the 1977–1988 period (Model 2) and the 1989–2000 period (Model 3).

Model 2 shows that the spread of electoral competition during the early phase of government-controlled elections in the 1980s, when the PRI remained as a hegemonic party, had a net positive and linear effect on indigenous protest. Every step that leftist opposition parties took away from PRI’s electoral monopoly was associated with a net increase in indigenous protest. However, Model 3 shows that the impact of electoral competition on protest became nonlinear only after the Left became a prominent national political actor and as elections became increasingly competitive in the 1990s. Once ENP reached a maximum at 2.2, protest began to decline. Footnote 63

Controls. The results shown in table 1 confirm that other factors besides elections did have an impact on indigenous protest. Major neoliberal economic policy reforms were an important stimulus for protest. The results suggest that protest did not take place in small ethnically homogenous municipalities but in large heterogeneous ones, where Catholic social networks and leftist parties—rather than PRI rural corporatist structures—provided the mobilizing vehicles and resources for indigenous collective action. Government repression did not deter but stimulated protest.

Controlled comparisons. To more effectively isolate the individual effect of electoral competition on the intensity of indigenous protest, consider the cases of the neighboring Mayan municipalities of Altamirano and Las Margaritas in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas—two municipalities with similar economic and demographic structures, shared historical grievances, and similar capacities for collective action.

Located in the eastern part of the state in the Lacandón jungle, Altamirano and Margaritas are predominantly indigenous, rural, and poor. Both places are inhabited by Mayan peasants who had escaped from private fincas (haciendas) and plantation systems to establish ejidos (state-owned small land plots awarded by the government to the rural poor). In response to the spread of Protestantism, in both places pastoral agents from the Catholic Church actively promoted the development of a wide variety of associational networks, including rural economic cooperatives.

Despite having shared grievances and similar organizational vehicles for collective action, Mayan peasants in Altamirano only engaged in episodic protest, but their co-ethnics in Margaritas were at the forefront of major cycles of peaceful mobilization. A crucial difference between these municipalities is that leftist parties made significant inroads into Margaritas in the late 1970s but in Altamirano only in the late 1990s. Model 1 predicts that during the 1980s protest in Margaritas would be at least 50 percent greater than in Altamirano. The raw data show that indigenous collective action was indeed significantly greater in Margaritas.

Micro-histories and causal mechanisms. While the controlled comparison between Altamirano and Margaritas shows that the active presence of leftist parties explains the difference in protest activity between the two municipalities, it does not explain the motivations that led leftist parties to promote indigenous mobilization in Margaritas nor the incentives that moved rural indigenous movements to embrace the electoral goals of leftist parties. To understand the marriage of the ballot and the street in Margaritas, we need to historically trace the incentives that explain the rise of socio-electoral coalitions and the co-evolution of elections and protest.

After Mexican authoritarian elites legalized the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) in 1977, leftist parties moved to the countryside to build an electoral base. They sought to recruit two types of local indigenous leaders in Margaritas: young Mayan bilingual teachers and Catholic catechists. These were local community leaders with long-term horizons and access to extensive social networks. They were risk-accepting individuals with strong policy preferences for land redistribution and social justice (catechists) and for indigenous cultures and rights (bilingual teachers).

Under the initial sponsorship of the PCM, Margaritas became a focal point for the rise of one of the most powerful rural indigenous organizations in Chiapas, the CIOAC (Independent Agricultural Workers and Peasants Central). Footnote 64 While the leadership of the movement was mostly secular—state-trained bilingual teachers—the activists and social base came primarily from Catholic social networks.

The CIOAC was the result of an unlikely alliance between communism, Mayan cultures, and Catholicism. While communist leaders were staunch atheists inspired by the Cuban Revolution, Catholic communities were anti-communists who believed the Cuban Revolution was a major threat to religious liberties. While communist leaders supported abortion, sexual liberation, and gender equality, Catholics were strongly conservative on social issues. Both groups did share, however, a similar antipathy to economic injustice. This shared element notwithstanding, communists and Mayan Catholic communities did not come together in the 1970s.

The introduction of government-controlled multiparty elections opened up possibilities for the rise of a strategic partnership between leftist parties and Mayan Catholic communities. But their ideological differences raised the costs of a socio-electoral coalition. Catholic communities believed that entering into the electoral arena would force them to give up on land invasions and lead them into a path of moderate negotiations with the government for token economic subsidies and financial support.

The prospects for electoral growth that CIOAC’s extensive social base offered them led leftist parties to embrace the movement’s key claims, even if these clashed with their party ideology. By the early 1980s, leftist parties in Chiapas had become major sponsors of CIOAC land invasions and rural indigenous mobilization. Leftist representatives in the Chiapan state legislature provided financial resources, bus transportation and lodging when CIOAC members led demonstrations in the capital city of Chiapas, and became a major institutional voice for land reform and human rights respect when the state responded to CIOAC actions with repressive measures. Footnote 65 When CIOAC leaders embraced a program for ethnic autonomy, leftist leaders were strategically supportive, even if they considered ethnic identities to be a case of “false consciousness.” Footnote 66 Leftist leaders even supported Catholic CIOAC members when they violently opposed the growth of Evangelical churches in their villages. Footnote 67

In exchange, Catholic CIOAC activists and members became increasingly politicized throughout the 1980s. Their initial struggle for land redistribution expanded into a broader struggle for human rights respect, free and fair elections, and democracy. From 1982 on, CIOAC members played a vital role in every municipal, gubernatorial, and presidential election cycle, participating in campaign rallies, mobilizing voters for leftist parties, canvassing and serving as party representatives in electoral precincts, and subsequently leading major post-election mobilizations to denounce fraud. Footnote 68 With the support of the CIOAC, between 1982 and 1991 leftist parties received one-third of the vote in Margaritas.

Following the liberalization of land tenure in 1992, the rise of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in Chiapas and the outbreak of rebellion in 1994 splintered CIOAC communities between those that joined the Zapatista revolutionary coalition and those that remained part of a leftist socio-electoral coalition. Fearful that the Zapatista rebellion would spread beyond Chiapas and give rise to a national revolutionary coalition, authoritarian elites in Mexico surrendered government controls over the organization of federal elections through two major electoral reforms in 1994 and 1996. Footnote 69 A subsequent wave of subnational reforms between 1996 and 2000 made fraud in local elections increasingly harder to machinate. These reforms, together with a targeted anti-insurgency strategy against the EZLN, weakened the revolutionary route and empowered elections as a mechanism for social and political transformation.

As elections became increasingly free and partially fair and as a victory for the Left became a real possibility in Margaritas, leftist party leaders and candidates adopted more moderate political strategies. They encouraged CIOAC members to distance themselves from the EZLN, discouraged land invasions and radical mobilization, and endorsed cross-class and multi-ethnic coalitions with wealthy local businessmen and prominent mestizo middle-class leaders and professional associations from the municipal seat of Margaritas. Footnote 70 This catch-all strategy paid off in 2001 when the Left came to power for the first time in seven decades in Margaritas.

A series of consecutive leftist victories between 2001 and 2010 led to a radical transformation of the socio-electoral coalition that had facilitated the Left’s rise to power in Margaritas. Access to patronage allowed the partisan Left to absorb a significant number of CIOAC leaders and activists into government halls, leaving the streets empty of protest. Democratization and the electoral success of the Left had brought three decades of indigenous protest to an end in Margaritas. Footnote 71

The history of Altamirano, Margaritas’ neighbor, shows that a major cycle of protest did not emerge in villages where leftist parties had failed to make any significant inroads. Although the Catholic Church contributed to the creation of extensive associational networks and rural cooperatives in Altamirano, the absence of leftist parties prevented a few episodes of social protest from coalescing into powerful cycles of peaceful mobilization. At the same time, the absence of leftist parties also provided an opportunity for the EZLN to absorb Catholic communities into a revolutionary coalition. Once the EZLN had been politically marginalized, the absence of a socio-electoral coalition prevented the development of a strong partisan Left in Altamirano. Unlike Margaritas, where the Left and the CIOAC became dominant actors in municipal politics, in Altamirano former PRI elites ruled the municipality under a leftist façade.

Election Cycles and Concurrent Elections as Magnets for Indigenous Protest

We have provided quantitative and qualitative evidence showing that the introduction of government-controlled multiparty elections and the spread of electoral competition across Mexican indigenous municipalities shaped the rise and demise of a powerful cycle of indigenous protest. In this section I test whether protest became significantly more intense during elections.

The results presented in Table 2 show that election cycles had an important effect on the intensity of indigenous protest (H.2.a). Model 4 shows that indigenous protest increased by 29.5 percent in presidential election years (IRR = 1.295; H.2.b). The results also show that gubernatorial election cycles depressed protest by 15.5 percent (IRR = 0.845) and that municipal election cycles had no effect on indigenous collective action.

Table 2 Election cycles and indigenous protest in Mexico, 1975–2000 (random effects negative binomial models)

* p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. Standard errors in parentheses. One-year lag of Protest and South not shown. IRR = incidence rate ratio.

Because election calendars are mixed in Mexico, the true impact of election cycles on protest was conditional on whether national elections were concurrent with subnational elections (H.2.c). The interaction of presidential and gubernatorial elections in Model 5 shows that protest was 154.6 percent (IRR = 2.546) higher in municipalities from states in which governors were elected concurrently with the country’s president.

The constitutive terms of the interaction effect provide crucial information. Results in Model 5 show that presidential elections actually had no effect on protest when there were no concurrent gubernatorial elections (IRR = 0.995). Results also show that gubernatorial cycles depressed protest by 42.1 percent when state elections were non-concurrent with presidential election cycles (IRR = 0.579). These findings suggest that national elections were a focal point for indigenous protest only when presidents and governors were elected simultaneously—when indigenous communities used elections to bypass subnational authorities and express their local grievances in the national arena.

Controlled comparisons. To more effectively isolate the effect of concurrent presidential and gubernatorial elections on indigenous protest, consider the case of three neighboring southern states: Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero. These are the three poorest, most unequal, and most rural Mexican states. They have significant indigenous populations and considerable histories of state repression.

Despite these similarities, on a per capita basis Chiapas experienced twice as much protest on average as Guerrero and 3.7 times more protest than Oaxaca. Footnote 72 A crucial distinction between these three states is that whereas gubernatorial elections in Chiapas were concurrent with the presidential cycle, Guerrero and Oaxaca had staggered state elections. This simple and often overlooked institutional feature means that Chiapas attracts significantly more protest in presidential election years than do neighboring states. If we select two nearly identical indigenous municipalities from Chiapas and Oaxaca, with similar grievances, organizational capacity, and political histories, in a year of presidential elections we would expect to see 154.6 percent more protest in the Chiapan municipality than in the Oaxacan municipality.

Micro-histories and causal mechanisms. The window of opportunity that concurrent elections offered for mobilization did not escape the attention of indigenous leaders in Chiapas. Given that presidential, gubernatorial, and municipal elections were concurrent, CIOAC leaders knew that mobilizing their local causes during election campaigns would result in uncommon public attention. Footnote 73 They also knew that in election years national and state-level leftist party leaders would be more willing to provide them with extensive resources to undertake action in the streets. Finally, they knew that during election cycles national elites would have incentives to constrain the repressive inclinations of subnational elites.

The window of opportunity offered by the simultaneous election of presidents and governors did not escape the attention of the EZLN, either, when the rebels decided to declare war on the Mexican government on January 1, 1994. While most interpretations of the timing of the outbreak of the Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas point to NAFTA’s coming into effect in 1994, the fact that 1994 was also a year of presidential and gubernatorial elections was a crucial factor in deciding the date of the rebellion. Subcommander Marcos—the Zapatista military strategist and spokesman—was clear about the importance of election calendars in accounting for the timing of the rebellion:

Even though [by 1993] the regime seemed to be strong, we knew it was vulnerable. We knew [that if we rebelled in January 1994] all we had to do was fight and not give up until the [August] presidential elections . . . . We knew that if we succeeded, the government would have to call a ceasefire and enter negotiations in order for the elections to take place.

We thought that if the government tried to annihilate us through a counter-insurgency campaign, the murder of indigenous peoples [in a presidential election year] would shake up the country and the world’s public opinion, shifting their attention toward our cause—the Indians, the forgotten ones. Footnote 74

The Zapatista rebels understood the mechanics of agenda setting very well. They knew that a movement’s message can be amplified and receive unprecedented attention in a presidential election year. They also knew that the repressive will of national governments declines in a presidential election year and a dissident group’s ability to force negotiations and government concessions is significantly higher. The fact that gubernatorial elections in Chiapas were concurrent with the presidential cycle increased the incentives to take up arms in 1994. And so they did. Footnote 75

Authoritarian Elections and Protest beyond Mexico

A major concern for any theory that is tested using evidence from a single country is whether the results are generalizable beyond national borders. The experience of three military regimes in twentieth-century Latin America provides reasonable evidence showing that electoral incentives can shape cycles of protest in a number of authoritarian regimes beyond Mexico.

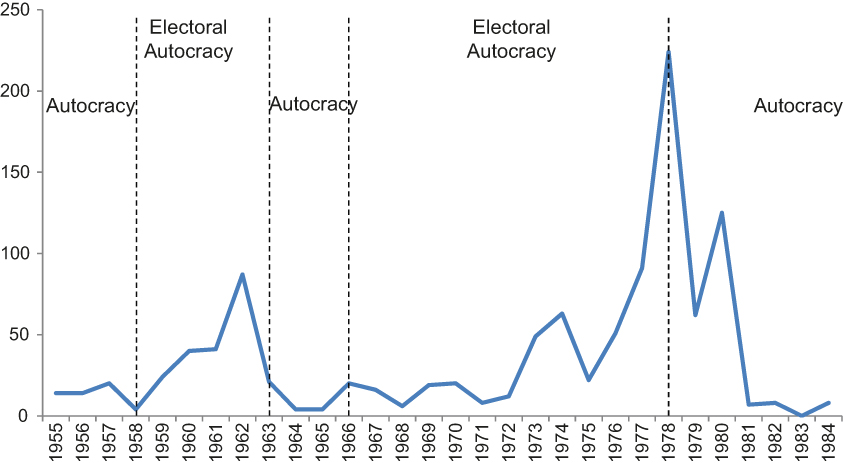

Guatemala. After the military junta introduced government-controlled multiparty elections for the selection of presidents, legislators, and mayors in 1958 and then in 1966, Guatemala experienced two substantial cycles of protest, as shown in figure 3A. Footnote 76 To simultaneously fight fraud and build an electoral constituency, Leftist and Christian Democratic parties developed strategic partnerships with Catholic-sponsored rural indigenous movements, workers unions, and student movements and became major sponsors of their causes. These socio-electoral coalitions facilitated the aggregation of isolated movements into major cycles of mobilization. As figure 3B shows, although protest increased significantly during presidential election years, particularly when national elections were concurrent with local elections, as was the case in 1966, 1970, 1974, and 1978, protest persisted beyond elections. A harshly repressive military reaction to the intensification of protest and the retraction of civil rights in the late 1970s led to the end of peaceful mobilization and to civil war. Footnote 77

Figure 3A Political regimes and social protest in Guatemala

Source: Brockett, Reference Brockett2005.

Note: Regime classification is my own.

Figure 3B Cycles of presidential elections and social protest in Guatemala

Note: Arrows identify presidential election cycles.

El Salvador. After the military junta consented to government-controlled multiparty elections for legislators and mayors and subsequently for the presidency, El Salvador plunged into a period of mass mobilization in the 1960s and 1970s. Footnote 78 Powerful socio-electoral coalitions between Leftist and Christian Democratic parties and teacher and labor unions, student movements, peasant movements, and Catholic grassroots communities enabled the development of a major cycle of protest. Protest reached its highest peaks during election cycles, particularly when mayors and presidents were elected simultaneously, as was the case in 1967–1968 and 1971–1972. As in Guatemala, harsh military repression and the retraction of rights in the late 1970s led to the demise of protest and to civil war. Footnote 79

Brazil. After the military junta introduced a series of liberalizing reforms in 1974 and government-controlled multiparty elections in 1979, Brazil plunged into an unprecedented cycle of protest. Popular mobilization was led by two powerful socio-electoral coalitions between the two major leftist parties—the Brazilian Democratic Movement and the Workers’ Party—and labor unions, student movements, urban popular movements, and Catholic grassroots movements. Protest became more intense around national elections in 1978 and in the months leading up to the 1984 presidential election, when an opposition party was elected. Brazil’s cycle of protest incrementally came to an end after the completion of the country’s transition to democracy. Footnote 80

Beyond Latin America, powerful socio-electoral coalitions led major cycles of mobilization in electoral autocracies in other world regions.

Philippines. After six years of martial law, once President Ferdinand Marcos consented to government-controlled multiparty elections in the Philippines in 1978, the country plunged into a major cycle of mobilization that ended after Marcos’s defeat in 1986. A powerful socio-electoral coalition between opposition parties and students, urban popular movements, professional associations, and Catholic-sponsored grassroots movements led a wave of mobilization that became more intense in the 1978 and 1984 legislative elections, the 1980 local elections, and the 1986 presidential election. Although violent revolutionary change remained a possibility up until 1985, a split in Marcos’s coalition following the stolen 1986 election strengthened the path of non-violent regime change. Footnote 81

Algeria. After the military-backed government introduced a major political reform that legalized all political parties and put an end to single-party rule in 1989, Algeria plunged into a major cycle of peaceful mobilization. Protest was led by a powerful socio-electoral coalition between the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS)—the country’s main opposition party—and a multiplicity of grassroots Islamic organizations, charities, and cultural NGOs. Footnote 82 While the FIS embraced the cause of their social allies, grassroots organizations led mass mobilizations during electoral campaigns and major demonstrations to contest authoritarian changes in electoral laws. Successive FIS electoral victories in local and legislative elections and the struggle for free and fair elections galvanized a national socio-electoral coalition and marginalized the most radical armed Islamic revolutionary groups. A military coup to prevent the FIS from coming to power and the reversion of civil and political rights, however, brought the cycle of peaceful mobilization to an end and paved the way to civil war.

China. The absence of multiparty elections in China, the world’s largest autocracy, helps explain why hundreds of local and highly circumscribed protest movements have failed to coalesce into powerful regional or national cycles of mobilization. Footnote 83 Although Chinese national authorities have consented to the selection of local authorities through village-level elections, opposition parties are banned from competition. The de jure exclusion of opposition parties in China has prevented the aggregation of parochial local protest movements into national cycles of mass mobilization and has undermined the power of the street.

The Ballot and the Street

In an influential essay, McAdam and Tarrow recently noted that one of the most surprising shortcomings in the study of collective action and social movements is the absence of an adequate explanation of the reciprocal relationship between elections and social protest. While McAdam and Tarrow and others have begun to develop a systematic explanation of this relationship in democracies, Footnote 84 I have outlined and tested here a systematic explanation of the relationship between the ballot and the street in electoral autocracies.

I have suggested that when autocrats introduce government-controlled multiparty elections they politicize the ballot and the street. Because opposition parties in electoral autocracies have to compete for office while contesting the rules of electoral competition, opposition party leaders have powerful incentives to recruit social movement activists to help them fulfill their dual electoral goal. Social movements can play a key role mobilizing voters during electoral campaigns and in post-electoral mobilizations to denounce fraud. Recruitment, however, is not easy because electoral participation can create internal divisions within social movements. To overcome this obstacle, opposition parties often become major sponsors of social movement causes, provide major financial and logistic resources for mobilization in non-election times, and become an active institutional voice to denounce human rights violations against social activists.

My evidence has shown that when opposition parties succeeded in recruiting social movements and developing powerful socio-electoral coalitions, this partnership gave rise to major cycles of protest. Within these cycles, protest was more intense during elections—when a wide variety of social movements coordinated their actions in the streets to advance the opposition electoral cause—but persisted beyond elections—when individual social movements took to the streets to demand government responses to their particularistic claims. I have provided quantitative and qualitative data showing that socio-electoral coalitions played a crucial role in the spatial aggregation of local and isolated protest movements into major cycles of mobilization and in the temporal aggregation of electoral and non-electoral protest. These major cycles of mobilization persisted as long as elections were partially free and unfair but began to dwindle as elections became freer and the prospects of electoral victory led opposition parties to partially demobilize the street.

While the theory outlined here clearly builds on the influential literature on post-electoral protest in autocracies—particularly on studies of the Color Revolutions in Eastern Europe—my theoretical propositions and empirical findings expand our current understanding of protest in autocracies in three important ways.

First, unlike explanations that emphasize the spontaneous and decentralized nature of post-election protest, I have shown that social protest in electoral autocracies is not necessarily spontaneous, decentralized, and unorganized. Consistent with the influential work of Bunce and Wolchik, I found that social movements played a key role absorbing the initial costs and solving the logistical problems associated with the organization of mass mobilization during election campaigns and in post-election protests to contest fraud. Social movements were leading actors in the formation of the critical mass for participation cascades. As mobilization became larger, unorganized participants may have spontaneously taken to the streets, but in the absence of the social activists’ initial actions the participation of the “crowd” would have been unlikely.

Second, unlike prevailing explanations that emphasize the causal role of social grievances, moral outrage, or the natural proto-democratic tendencies of social movements as motivations for protest participation in autocracies, I have shown that instrumental motivations played a key role in driving organized social movements to the streets. My findings show that social movements led social mobilization during election cycles and helped opposition parties fulfill their dual electoral goal of competing while contesting election fraud only when parties could credibly offer social movement leaders and activists a stream of resources and support to mobilize for their own causes in non-election times. While emotions or information conveyed by the announcement of fraudulent election results may have guided the unorganized masses to the streets, a long-term instrumental exchange with opposition parties was a crucial factor in driving social movement action in the first place.

Third, unlike the literature on the Color Revolutions, which focuses on post-election mobilization in stolen elections, and conceives mobilization as a one-shot game, my evidence shows that protest in electoral autocracies is an iterative process in which a quid pro quo between social movements and opposition parties facilitates the inter-temporal connection between electoral and non-electoral protest and contributes to sustain cycles of mobilization that can last for several years—as the evidence from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Brazil, the Philippines, and Algeria shows. Within these broad cycles of mobilization, protest is indeed more intense during election cycles but persists beyond elections—as the time series data from Mexico and Guatemala show.

Understanding the rise, development, and demise of cycles of protest is crucial to explain the prospects of stability and change in authoritarian regimes. While elections are not the only mechanism of aggregation of individuals and local movements into major cycles of protest in authoritarian regimes, Footnote 85 electoral incentives can play a decisive role in mobilizing the street. When autocrats introduce government-controlled multiparty elections, they open important opportunities for change, even if their intent in reforming is to stay in power, not to relinquish it. However, whether partially free and unfair multiparty elections become a mechanism of authoritarian stability or regime change largely depends on the ability of states and opposition forces to gain control over the street. Footnote 86 As I have shown here, when opposition parties and social movements can develop powerful incentive systems that help them overcome their natural differences and align the clout of the ballot and the street against authoritarian incumbents, their strategic cooperation will open up important possibilities for peaceful regime change and democratization.

The marriage of the ballot and the street can be a determining factor in the removal of authoritarian leaders who fail to accept electoral defeat Footnote 87 (e.g., the Philippines) or in making elections increasingly free and fair and paving the way for democratization by elections (e.g., Brazil and Mexico). The successful coalition-building experience of opposition parties and social movements in these countries can help us understand the possibilities available to opposition forces seeking the democratization of some of the most emblematic twenty-first century electoral autocracies, from Russia to Venezuela.

But the marriage of the ballot and the street can also be a crucial factor in keeping social mobilization on a path of peaceful contestation. When authoritarian incumbents adopt a strategy of incremental electoral liberalization to stay in power, opposition socio-electoral coalitions tend to prevail over revolutionary coalitions and often lead countries on a path of democratization by elections (e.g., Brazil and Mexico). In contrast, when incumbents give up on political liberalization and dismantle limited electoral rights and civil liberties, they weaken socio-electoral coalitions, undermine the electoral path of social transformation and open the way for armed revolutionary action (e.g., Algeria, El Salvador, and Guatemala). The experience of how the retraction of political rights and civil liberties upset the balance of power between socio-electoral and revolutionary coalitions in these countries should be a warning of the latent risk of an armed insurgency breaking out in Egypt—the most emblematic country of the Arab Spring.

Although the study of social movements and social protest and the study of political parties and elections have been compartmentalized into separate intellectual fields in the social sciences, I have shown that a systematic analysis of the reciprocal relationship of the ballot and the street can significantly improve our understanding of cycles of social mobilization and dynamics of stability and change in authoritarian regimes. Looking ahead, a systematic comparison of the electoral incentives that can drive social movements and political parties to the street and of the political consequences of street mobilization in autocracies and democracies would significantly expand our current understanding of dynamics of protest in contemporary societies.