Among the most compelling developments of the last decades within the field of political theory has been the steady advance of comparative political theory (CPT), a diverse literature dedicated to studying traditions of political thought that have not traditionally been studied by Western European and North American political theorists. In their work, comparative political theorists have described the distinctive problems that animate Asian, African, Middle Eastern, and Latin American political thought, highlighting the profound challenges that ideas originating in these regions pose for Western European and North American orthodoxies. CPT’s interventions have also inspired extensive and fruitful methodological reflection, raising important questions about the procedures that political theorists apply when they select texts for study, interpret their passages, and assess their arguments (von Vacano 2015).

In their efforts to develop methods of reading and engaging with unfamiliar ideas and intellectual traditions, comparative political theorists have adapted approaches from anthropology, literary criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history. But, despite the modifier, comparative political theorists have not derived much methodological inspiration from the subfield of comparative politics. Indeed, as I argue below, in several foundational statements comparative political theorists have outlined approaches that are actually incompatible with the comparative methods used in comparative political science,Footnote 1 and in most cases this incompatibility is intentional. Comparative political theorists have not neglected, but rather rejected, comparative politics as a model for their inquiries, because they argue that applying the comparative method would compromise both the interpretive and the critical projects that CPT should pursue.

In this article, I describe a comparative approach for the study of political ideas that would help comparative political theorists answer some of the interpretive questions that they are already asking, while also expanding the range of critical arguments that comparative political theorists could make. Specifically, I show that the comparative method offers unique insight into why political thinkers in different times and places have thought and written in the different ways that they have, allowing us to see how the intellectual and institutional contexts that authors always occupy influence their ideas. Improving our understanding of how the contexts within which political thinkers live and work cause variations in their ideas opens the way to new kinds of critical argument, providing a foundation for both deconstructive critiques that reveal the partial interests that political ideas presented as universally advantageous actually serve, and for reconstructive critiques that identify particular thinkers or traditions of political thought that, because of the contexts in which they developed, offer compelling critical perspectives on existing political institutions. Although I develop this comparative approach primarily in reference to recent work in CPT, it can be applied as productively to texts composed in Europe and North America as to the Asian, African, Middle Eastern, and Latin American ideas and intellectual traditions studied by comparative political theorists.

The article proceeds in four parts. First, I review the literature on CPT’s aims and methods, noting how the influence of some methodological “schools” familiar from the history of political thought has contributed to the development of approaches to CPT that are incompatible with the comparative method. I show that Straussian political philosophy, Gadamerian philosophical hermeneutics, and Skinnerian contextualism, in different and instructive ways, present obstacles to using comparisons to explain why similar and different political ideas arise in similar and different circumstances. By contrast, I argue that Marxian ideology critique, an approach that has exerted less influence on CPT, offers a more promising framework.

Next, drawing on efforts to incorporate the study of ideas into historical institutionalism, I offer a revised account of political ideas as ideologies, proposing that we treat political ideas as having been caused by the background problems that their thinkers set out to solve. Although these background problems are in every case particular, reflecting the idiosyncratic experiences and creativity of the political thinkers who addressed them, I argue that they are also partly determined by generalizable contexts that can be usefully compared across time and over space. Specifically, I suggest that background problems can be described as the products of an interaction between the institutional and intellectual contexts that every political thinker occupies, and I explain how individual political ideas emerge from these contexts and contribute to their revision over time.

In the third section, I show how political theorists aiming to explain variation in political ideas can use the comparative method employed by qualitative political scientists and comparative-historical sociologists. I devote particular attention to the issue of case selection, adapting John Stuart Mill’s ([1843] 1974) methods of “difference” and “agreement” to the problem of explaining points of ideological convergence and divergence among political thinkers who occupied similar and different institutional and intellectual contexts.

In the fourth section, I argue that using the comparative method to interpret and explain political ideas need not impair CPT’s critical projects nor doom the prospect of discovering compelling perspectives on contemporary political issues in unfamiliar intellectual traditions. I describe how the approach could instead advance these projects, both by systematically provincializing the European and North American political thinkers whose works comprise the canon and by identifying the unique critical insights available in both western and nonwestern texts composed in circumstances that hindered canonization.

Comparative Political Theory and the Comparative Method

In an early account of the purpose and promise of CPT, Anthony Parel (1992) likens modern western political philosophy to the upas tree, a tropical species that was once widely believed to emit a poisonous miasma, killing everything under its branches and leaving behind a wasteland of withered plants and animal skeletons. In Parel’s account, the global spread of modern western political thought, particularly in its liberal and socialist variants, had wreaked similarly noxious effects on the world’s intellectual diversity. Western political thinkers presented their ideas as the “products of universal reason itself,” while dismissing the ideas of their nonwestern counterparts as outgrowths of peculiar cultural environments, curious but unworthy of serious consideration as guides to how we should live. The “comparative study of political philosophy,” Parel suggests, provides a “neutralizing antidote” to modern western political thought’s malignant influence, by vindicating the claims of certain nonwestern intellectuals to recognition as participants in the timeless debates of political philosophy (11–28).

Taking his methodological bearings from Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin, Parel argues that “the comparative study of political philosophy … is nothing other than the process, first, of identifying ‘equivalences’”—similarities in key ideas or concepts that appear in the great western and nonwestern texts on politics—“and second, of understanding their significance.” Parel offers several examples of the kinds of equivalences he had in mind: “the Aristotelian politikos and the Confucian junzi, Indian dharma and the pre-modern western notion of ‘natural justice’, the Islamic prophet-legislator and the Platonic philosopher-king” (1992, 11–13). But he says less about how one is to understand the significance of these equivalences, and he says nothing at all about how comparative political theorists should choose texts to search for equivalences or about how they should derive implications from their presence or absence.

By contrast, Roxanne Euben (Reference Euben1997a) illustrates the important insights that CPT can produce, describing parallels between the Islamist philosopher Sayyid Qutb’s “moral indictment of post-Enlightenment political theories … that assume the exclusion of religious authority from the political realm” and the political thought of Western European and North American philosophers like Alasdair MacIntyre, Charles Taylor, and Robert Bellah, “who are similarly concerned with the ways in which rupture with tradition and transcendent foundations has resulted in crises in authority, morality, and community.” Euben argues that uncovering this equivalence “enables us to see past the alienness” of Islamic fundamentalism and recognize Qutb as “one voice in a larger conversation on rationalism and the modern condition, a conversation in which we too participate” (31, 53; see also Euben Reference Euben1997b; Reference Euben1999). This compelling insight immediately prompts one to wonder why these thinkers, who lived and worked in such distinctive circumstances, converged on an indictment of atheistic rationalism. Were shared intellectual influences at work? Were these authors, despite the distance between them, responding to similar political problems within their respective societies? Or was this a case of great minds thinking alike?

Addressing this puzzle, Euben considers and rejects the idea that “fundamentalism is a reflex reaction to certain political or socioeconomic circumstances,” insisting instead that “the increasing strength of fundamentalism … is at least partly related to the specific appeal of fundamentalist ideas” (1997a, 30). By tracing Qutb’s particularly profound intellectual influence, she argues that a causally adequate account of Islamic fundamentalism cannot depend solely on the political and economic circumstances within which fundamentalism has arisen, but must also take the intellectual merits of Islamist ideas seriously (1999, 154–67). This is an immediately plausible argument, but Euben’s case might have been made even stronger had she conducted comparisons specifically designed to disentangle the contextual factors that her interlocutors have claimed cause fundamentalism. Comparative political scientists apply diverse, but well-articulated standards when choosing cases for comparison, so that they can address alternative possible explanations for the phenomena they hope to explain. Adapting these standards might have helped increase our confidence in the explanation that Euben provides for the intellectual continuities that she documents.

Euben’s study of Islamic and western critiques of modernity exemplifies CPT’s ambiguous relationship with comparative political science. Although comparative political theorists have adopted the latter’s “comparative” modifier as a description of their work and, in some cases, addressed the kinds of questions that comparative political scientists are also interested in answering, they have not adopted the inferential methods characteristic of comparative politics. Instead, following Parel, in their efforts to understand texts written far away, comparative political theorists have adapted approaches developed to understand texts written long ago. Alongside Straussian political philosophy, the dominant “schools” within the history of political thought have exerted a strong influence on the methodological development of comparative political theory. For different and instructive reasons, the influence of these schools has, over time, made actual comparison a marginal approach within comparative political theory. Although this trend away from comparison has not prevented comparative political theorists from producing illuminating studies of diverse figures and intellectual traditions, or from deriving compelling critical insights from these studies, it has diminished the field’s capacity to explain the presence or absence of the kinds of ideological equivalences that Parel and Euben were interested in understanding.

The most influential school within comparative political theory has been the philosophical hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer ([1960] 1999). This is in many ways unsurprising. Gadamer’s well-known observation that modern scholars’ interpretations of historical texts or objects will always be “determined by the prejudices that [they] bring with [them]” (306) would seem to apply with equal if not greater force to western political theorists’ attempts to understand ideas originating in nonwestern philosophical traditions. As Raymundo Panikkar (Reference Panikkar, Larson and Deutsch1988) and Fred Dallmayr (Reference Dallmayr1997; Reference Dallmayr2004) have argued, Gadamer’s effort to mitigate this problem through what he described as a dialectical “fusion of horizons” offers not only interpretive but also ethical guidance to scholars who wish to engage unfamiliar intellectuals not as mere objects of curiosity but as live interlocutors.

Farah Godrej (Reference Godrej2009; Reference Godrej2011) has deepened these arguments, incorporating insights from postcolonial and poststructuralist philosophy that reinforce Gadamer’s emphasis on reflexively accounting for one’s own background and prejudices in encounters with unfamiliar intellectual traditions. Godrej recommends that comparative political theorists adopt a “hermeneutic of existential understanding,” which acknowledges that “the ideas in a text cannot simply be understood by an analysis of the concepts in the text itself; rather [understanding] requires a praxis-oriented existential transformation in which the reader herself learns to live by the very ideas expressed in a text” (2009, 140). Although this procedure offers a compelling account of what truly understanding an unfamiliar intellectual tradition would entail, it also restricts the kinds of comparisons that comparative political theorists can pursue, limiting scholars to their own native intellectual tradition—however defined—and to others whose tenets they not only could but actually have “lived by.” Indeed, although the comparative method demands separation between the comparing subject and the compared objects, for Godrej, CPT requires “precisely that the reader not see herself as separate from the text and that the subject not gaze at the object from a distance, attempting to achieve a scholarly objectivity in one’s understanding” (141, emphasis in the original). As Godrej’s work demonstrates, adopting this account of the relationship between reader and text opens the way to insightful inquiries, but it also forecloses most kinds of comparative study.

Different impediments to comparison arise in approaches to CPT inspired by Quentin Skinner’s (Reference Skinner2002) “contextual” method for studying the history of political thought. For Skinner, a political idea or text is “inescapably the embodiment of a particular intention on a particular occasion, addressed to the solution of a particular problem, and is thus specific to its context in a way that it can only be naïve to try to transcend.” Thus, “to understand what a writer may have been doing in using some particular concept or argument, we need first of all to grasp the nature and range of things that could recognizably have been done by using that particular concept, in the treatment of that particular theme, at that particular time.” More generally, “the aim is to see such texts as contributions to particular discourses, and … to return the specific texts we study to the precise cultural contexts in which they were originally formed” (88, 102, 125). The emphasis here, it should be clear, is on particularity. For Skinner, our understanding of historical texts improves with every improvement in our ability to avoid “anachronistic” misreadings by reconstructing the local linguistic conventions, contemporaneous rhetorical practices, and common literary genres that their authors drew on and revised.

Similarly, for Leigh Jenco (Reference Jenco2007), the most important impediment to understanding nonwestern texts is western scholars’ failure to absorb a background cultural environment that makes the concepts contained within these texts intelligible. Jenco advances this argument even further than Skinner, arguing that scholars engaged in cross-cultural inquiry should reconstruct not only the “substantive ideas” contained within a text but also the “culturally situated methods of inquiry” that the author’s local contemporaries employed, including “practices that complement text-based interpretive traditions, or that constitute traditions of their own—practices like imitation, ritual, dance, or other forms of nonverbal expression” (741 and 744). In other work, Jenco (Reference Jenco2014) argues that in order to avoid “assimilative” misreadings of nonwestern texts, comparative political theorists should strive to be “disciplined” by their encounters with unfamiliar thinkers, deriving the very methods of interpretation and critical engagement that they employ in those encounters from the intellectual traditions that they are encountering.

This is a challenging insight, but it places considerable obstacles in the path of a comparative political theory. The comparative method requires some abstraction and generalization. We must systematically reduce the details surrounding any given act of political thinking in order to grasp what different thinkers shared or did not share in terms of context and motivation and how their ideas converged or diverged as a result. Comparison also involves the application of a single interpretive and inferential method to thinkers who may or may not have shared a single method of inquiry themselves. To be sure, Jenco might not be concerned with asking or answering questions about why the thinkers she examines thought what they did, and I am not suggesting that one must ask or answer such questions in order to understand or to engage critically with political ideas. Rather, I mean only to observe that, if one aims to explain ideological similarities and differences across space and time, the approach to CPT that Jenco outlines presents some significant difficulties.

To overcome these difficulties, I suggest that we consider a school of thought that has, to date, exerted less influence on CPT than the others described above: Marxian ideology critique, or what Neal Wood (Reference Wood1978) described as “the social history of political theory.” Drawing inspiration from Marx’s ([1859] 1972, 4) classic maxim of historical materialism, “it is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness,” contemporary proponents of this approach criticize both abstract, “philosophical” engagements with the history of political thought, which read and evaluate prominent thinkers without reference to the contexts in which they lived and worked, and the particular kind of contextual history practiced by the Cambridge School, which usefully places texts against a background of contemporaneous rhetorical practices and linguistic conventions, but usually neglects to describe the “social contexts”—prevailing modes of organizing labor, distributions of property, electoral laws, rights regimes, and the conflicts arising from them—that shape political thinking (Ashcraft Reference Ashcraft1980; Wood Reference Wood2008, 8–9). Political ideas are political, Richard Ashcraft (1975, 20) writes, because they are closely related to “the maintenance or furtherance of the social, political, and economic objectives of … specifically identifiable group[s] within society.” Thus, for Ashcraft and other members of this school, an adequate account of any given text in the history of political thought must assemble evidence capable of supporting a description of the author’s position in the social and political struggles contemporaneous with the text’s composition.

Two interrelated features distinguish the Marxian approach and contribute to its compatibility with the comparative method. First, unlike the Gadamerian approach, ideology critique is not an attempt by the critic to approximate as closely as possible the mindset of historical political thinkers, to think their thoughts as they thought them, or to otherwise mitigate the distance between interpreters and the texts they interpret. Rather, the aim, as Karl Mannheim ([1926] 1971, 252) put it, is precisely to take advantage of the perspective that historical distance offers so as to interpret ideas “from without,” by reference to a social context that is “extrinsic” to the ideas themselves. Second, by contrast with the Cambridge School, social historians of political theory seek to connect the local controversies that give rise to particular texts with what Ellen Meiksins Wood (2008, 10-11) describes as “historical processes”: “long-term developments in social relations, property forms, and state formation” that unfold differently in different contexts and can thus be usefully compared. As Wood (2012, 18) notes in her social history of early-modern European political thought, “differences among the various patterns of property relations and the various processes of state-formation that distinguished one European society from another … produced different patterns of theoretical interrogation, [and] different sets of questions for political thinkers to address.” By comparing these patterns of political and economic development in England and France, and noting corollary variations in English and French political thought, Wood constructs a compelling case for her interpretation of John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government, among other texts that previous scholars had read very differently.Footnote 2 In this way, Wood’s work illustrates how Marxian ideology critique can be paired with the comparative method to refine our understanding of the history of political thought.

There are some important studies of nonwestern political thought that incorporate elements of Marx’s approach. Partha Chatterjee’s Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World (1986) offers an account of nationalist thinking within colonial societies comprising three “moments”—the “moment of departure,” the “moment of maneuver,” and the “moment of arrival”—that reflect the distinct interests and activities of different social sectors—an intellectual elite, the popular masses, and a colonial bourgeoisie, respectively—as each enters and influences a struggle for independence. Chatterjee acknowledges that “the theoretical structure of [his] argument must stand or fall at the general level, as an argument about nationalist thought in colonial countries and not as an argument about Indian nationalism,” but he does not pursue the comparisons that might support his case (50). More recently, Loubna El Amine (Reference El Amine2016) has argued that the convergent slogans that appeared in geographically and culturally distant events, such as the Arab Spring and the “Occupy Central” protests in Hong Kong, are best understood as “a common discourse of resistance to political authority that stems from facing common challenges brought about by shared material conditions”—specifically, the material conditions characteristic of “modernity,” defined centrally by reference to the modern, centralized, and bureaucratic state (103). El Amine’s study strongly suggests that a comparative approach to the study of political ideas, capable of systematically tracing ideological convergences and divergences back to the material contexts that produce them, could generate important interpretive insights. Below, I elaborate on how comparative political theorists could make arguments along these lines, but first I develop an account of how political ideas relate to the contexts in which they arise, which builds on Marxian ideology critique while modifying some of its assumptions.

Institutional and Intellectual Contexts

Comparison is, among other things, a powerful method of causal inference, a means of testing the validity of proposed explanations for why some event or events of interest occurred or did not occur. Here, I describe a comparative approach to explaining political ideas, but this raises immediate questions: In what sense can political ideas be said to have been caused? What is entailed in explaining why a given thought appeared where and when it did?

I propose a minimal, and, I hope, minimally controversial answer to these questions: political ideas are caused by the background problems that their thinkers set out to solve. Explaining why political thinkers thought what they did involves reconstructing the background problems that they aimed to address.Footnote 3 There are irrevocably particular aspects to the background problems that any given political thinker addresses in the course of a career, and any adequate explanation of a particular thinker’s work must reflect the influence of these idiosyncratic factors. But, at the same time, all political thinkers always occupy institutional and intellectual contexts that connect them with or distinguish them from other thinkers, and that interact to partially determine the background problems that they confront. The comparative approach I describe here is designed to discern the influence of institutional and intellectual contexts on the political ideas we wish to explain.

Institutional Context

By institutional context I mean the formal and informal rules that structure social interactions in the community where the political thinker whose thoughts we wish to explain lives and works. I make two important assumptions regarding institutional contexts. First, following Karen Orren and Stephen Skowronek (2004, 22–24), I assume that all political thinkers always occupy a “full” or “plenary” institutional context: one in which there are written or unwritten rules governing social interactions, and agents that enforce these rules using physical or other means of social suasion. In other words, no political thinker has ever occupied a “state of nature” void of any institutions; the political thinkers who have availed themselves of various forms of this famous thought experiment did so from within thoroughly institutionalized contexts, which partially determined the background problems that caused them to think and write in the ways that they did.

Second, following Jack Knight (Reference Knight1992) and James Mahoney (Reference Mahoney2010), I assume that, in general, institutions exist not as cooperative solutions to collective action problems, but as outcomes of conflicts over the distribution of political power, economic resources, and social prominence. Groups of actors devise and enforce the rules that make up an institutional context in order to secure distributional advantages at the expense of other groups of actors. When compared with an alternative set of institutions, these institutions may or may not be “socially efficient.” That is, they may or may not solve collective action problems and distribute the gains from these solutions in a manner that improves the lots of all the actors subject to them. As Knight (1992, 40) argues, generally, the social efficiency of institutions will depend “on whether the institutional form that distributionally favors the actors capable of asserting their strategic advantage is socially efficient.” Except in some theoretically interesting limit cases, then, institutions produce unequal distributive outcomes, systematically advantaging some groups and disadvantaging others, who would be better off under some alternative set of institutions. In this sense, as Mahoney (2010, 17) notes, institutions create collective actors: “a shared position as privileged (or not) within institutional complexes provides a basis for subjective identification and coordinated collective action.” Here, I shall refer to collective actors comprised of individuals who share a position within an institutional context and who, as a result, share distributional advantages or disadvantages, as classes.

Although I use a term that is often associated with Marxian social theory, I do not adopt unmodified the assumptions that distinguish Marxian concepts of class.Footnote 4 In particular, in order to construct an account of institutional context flexible enough to be applied to the diverse societies whose intellectual traditions form the subject matter of comparative political theory, I do not assume that the particular set of institutions governing the ownership and exchange of land, capital, and labor is fundamental within any given society at a given time. It is certainly true that, in many places throughout much of history, the various institutions that comprise an overall institutional context have reinforced one another, awarding political power, economic prosperity, and social prominence to the same class while facilitating the simultaneous political exclusion, economic exploitation, and social marginalization of other classes. However, this pattern of reinforcing institutions is not inevitable. Individuals and groups of individuals can be simultaneously advantaged by some institutions and disadvantaged by others within the institutional context that they occupy. As a result, they can belong to different classes at the same time (Wright Reference Wright1985, 19–63).

One particular form of institutional overlap deserves further treatment here, given its special relevance to comparative political theory. From at least the sixteenth century, the institutions that structure differential group advantages have existed at multiple, nested levels of aggregation, comprising what the historians and social scientists of the Annales, dependista, and world-systems schools have called “world-economies”: “large geographic zones” containing multiple political units and characterized by an “axial” division of labor between “core,” “peripheral,” and “semi-peripheral” economies. Within world-economies, the relative monopolization of certain industries by a small number of political units—the “core”—facilitates a steady transfer of profits from other political units—the “periphery”—that are unable to establish or maintain monopolies in their industries (Wallerstein Reference Wallerstein2004, 23–41). The existence of a world-economy, then, distributes advantages and disadvantages unequally between groups, creating classes that are themselves internally divided by the institutions of the polities and localities that comprise the world-economy. Thus, it is possible for an individual to belong to a class that is relatively advantaged by a local distribution of political power or social prestige while belonging simultaneously to a larger class that is relatively disadvantaged by a global distribution of the profits from international commerce: such is the condition of many elite intellectuals situated in the peripheries of world-economies. Conversely, it is possible for an individual to belong to a class that is relatively disadvantaged by a local distribution of political power or social prestige while belonging simultaneously to a larger class that is relatively advantaged by a global distribution of the profits from international commerce: such is the condition of many working-class, nonwhite, and nonmale intellectuals situated in the cores of world-economies (Mies Reference Mies1986).

From these assumptions, it follows that all societies contain classes with contrary interests. Classes that derive advantages from existing institutions will be interested in maintaining those institutions. Classes that are disadvantaged by existing institutions will have contrary interests in reforming or abolishing those institutions and replacing them with others. The presence of classes with contrary interests leads to conflicts, which may remain latent or become salient at any given time. When conflict over a particular institution or set of institutions becomes salient, spokespersons emerge to offer arguments as to why existing institutional arrangements should be maintained, reformed, or abolished and replaced by others that would distribute advantages and disadvantages differently. These spokespeople are political thinkers, and their arguments are political thoughts. This is not to say that the interests derived from institutional contexts form the sole motivation for political thinking or that all political thinkers are merely spokespersons for the interests of their own respective classes.Footnote 5 It is, however, to say that all political thinkers always live and work in institutional contexts characterized by class conflicts, which in important respects determine the background problems to which their ideas respond.

As Rogers Smith (2014, 131–32) has described, political ideas provide a basis for organizing coalitions to support either maintaining existing institutions or reforming or abolishing them and replacing them with alternatives (see also Smith Reference Smith, Shapiro, Skowronek and Galvin2006). The fact that individuals and groups may belong to multiple classes at the same time is critical, because it means that any given institutional context can give rise to different coalitions, leaving the outcome of conflicts indeterminate. Political thinkers may deploy ideas in an attempt to build consciousness and coordinate collective action among members of a class that is directly advantaged or disadvantaged by the particular institution or set of institutions that they hope to maintain or to reform, but they may also attempt to attract support from members of other classes with more ambiguous or even opposed interests in the existing institutional order.

In the service of these distinctive coalitional aims, political thinkers will deploy distinctive arguments. Arguments intended to mobilize the members of a particular class will emphasize the selective advantages that members of that class will derive from the maintenance, reform, or abolition and replacement of a given institution. Political theorists are generally less interested in this kind of argument than they are in those that insist on the more widespread or even universal benefits that are derived from existing institutions or that would be derived from some alternative institutional arrangement. Marxian historians of political thought since Marx himself have identified this universalizing tendency as a central feature of “ideologies,” both status quoist and revolutionary. In The German Ideology ([1845–46] 1973, 173–74), Marx and Engels observed,

Each new class that [would] put itself in the place of [the] one ruling before it is compelled, merely in order to carry through its aim, to represent its interest as the common interest of all the members of society. That is, expressed in ideal form: it has to give its ideas the form of universality, and represent them as the only rational, universally valid ones. The class making a revolution [presents itself] from the very start, … not as a class but as the representative of the whole of society; it appears as the whole mass of society confronting the one ruling class.

Many comparative political theorists share Marx’s skepticism concerning “the spurious ‘universality’ traditionally claimed by the [political thinkers of the] Western canon” (Dallmayr Reference Dallmayr2004, 252–53). Modified according to the terms described above, Marxian ideology critique can challenge both western and nonwestern political thinkers’ universalist pretensions by revealing the partial interests served by the institutions that their arguments defended.

Intellectual Contexts

Beginning in the interwar period, a group of Marxist intellectuals united less by personal connections than by shared experiences of repression and disappointment initiated a transition in Marxist theory, putting aside their predecessors’ predominantly economic and strategic analyses to address questions concerning epistemology and culture. In different ways, “Western Marxists” from Lukács and Gramsci to Adorno and Marcuse argued that the arts and ideas that Marx himself occasionally dismissed as superstructural reflections of class conflict in fact play an important role in determining the actions of classes and the outcomes of conflicts (Anderson Reference Anderson1979). Contemporary institutionalist scholars interested in the role of ideas in politics have made similar arguments, insisting that the attitudes that individuals form regarding the institutions that structure their interactions with other individuals are not straightforward reflections of the advantages and disadvantages that they derive from those institutions. Rather, these attitudes and the actions that they inspire are more proximately determined by individuals’ perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages that they derive from existing institutions; by the opinions they hold regarding the principles of justice in the distribution of power, prosperity, and prominence; and by the beliefs they develop about what alternative institutional arrangements are possible and how they would affect the world. Ideas, in other words, do not simply reflect the interests of classes privileged or underprivileged by institutions but also mediate the translation of institutions into perceptions, opinions, and beliefs, independently influencing the actions of classes and the transition of conflicts from latency to salience (Béland and Cox Reference Béland and Cox2011; Blyth Reference Blyth1997; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2002; Berman Reference Berman2006; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008).

We can incorporate these important insights into an account of political ideas as ideologies by describing the background problems that cause political ideas as the products of an interaction between thinkers’ institutional context and their intellectual context. Because, as I assumed above, institutions result from social conflict and because, as I have argued, social conflict is accompanied by political thinking, all political thinkers always occupy not only an institutional context but also an intellectual one. Intellectual contexts are comprised by the arguments that previous political thinkers offered on behalf of their preferred institutional arrangements as they intervened in the conflicts salient in their own societies. Some political thoughts remain behind long after their thinkers have succeeded or failed in having their institutional preferences realized—indeed, long after their thinkers have passed from the scene—preserved in printed books and pamphlets, in collections of complete works, and in abridged and annotated student editions. Notably, any given thinker’s intellectual context can be comprised in part by arguments that arose during social conflicts in institutional contexts separated by space and time from his or her own. Ideas about institutions travel much more readily—in both translated and untranslated versions—than institutions themselves.

Intellectual contexts interact with institutional contexts in three related ways to produce the background problems that cause political thinkers to think and write in the ways that they do. First, intellectual contexts mediate political thinkers’ perception of their institutional contexts, highlighting the distributional consequences of particular institutional arrangements. Institutions that have been the subject of intense or recent social conflicts, whether within a political thinker’s own society or in some other, communicatively-linked society, are more likely to become the subjects of salient social conflicts than those that have never produced salient social conflicts in any communicatively-linked society (Weyland Reference Weyland2009). Second, intellectual contexts influence political thinkers’ positive and normative analyses of their institutional contexts' distributive consequences, supplying ready-made reasons for finding particular institutional arrangements effective or ineffective and just or unjust, and thus for supporting efforts to maintain, reform, or abolish and replace them (Blyth Reference Blyth2002). Third, intellectual contexts provide a set of concepts and a language that political thinkers repurpose to construct and convey their own arguments in defense of existing institutions or on behalf of proposed reforms (Skowronek Reference Skowronek2006). In other words, no political thinker ever starts from scratch. Existing ideologies both inspire and constrain the creation of new ideologies (Elster Reference Elster1985, 469).

Political theorists and intellectual historians interested in the history of political thought have developed very good interpretive tools and analytical categories for studying intellectual contexts. Quentin Skinner and J. G. A. Pocock refer to “languages,” “discourses,” and “broader traditions and frameworks of thought”, which supply the set of terms and concepts that individual political thinkers use when they intervene in the political debates particular to the time and place in which they lived (Pocock Reference Pocock1985, 1–34; Skinner Reference Skinner2002, 103–27). Mark Bevir (Reference Bevir1999) offers a related, but distinct, definition of “traditions,” as “webs of beliefs” passed from teacher to pupil and subsequently modified by pupils before being passed on again. He argues that individual political thinkers and aspects of their thought can be partially explained by “locating” them in the traditions that provided the “starting point” from which they departed (174–220). Finally, Michael Freeden (Reference Freeden1996) brings us back to a term used above, outlining an approach to analyzing the “distinctive configurations of political concepts” that constitute political “ideologies,” such as “liberalism,” “conservatism,” and “socialism.”

These authors make different assumptions about how existing “discourses,” “traditions,” or “ideologies” influence the work of individual political thinkers, but to return to a point made above, they all tend to present intellectual contexts as the only kind of context relevant to the explanation of political ideas. The account of political ideas as ideologies developed here differs in emphasizing how intellectual contexts interact with institutional contexts, personal experiences, and the idiosyncratic spark of human creativity to create the background problems that cause political ideas. Distinguishing the influence of these different factors is a difficult task, but one to which the comparative method is uniquely well suited, as I demonstrate in the next section.

Comparative Explanation of Political Ideas

Different thinkers may be more or less explicit about the background problem or problems that caused them to think about politics in the ways that they do. Indeed, they may even be more or less conscious of those problems, depending on how deeply they interrogate their own institutional positions, interests, and inherited vocabulary and concepts. Thus, very often, reconstructing the institutional and intellectual contexts that interacted to create the background problems to which a given text responds takes scholars between the lines or off the page, leading to possible disagreement with other scholars that cannot be resolved either by direct appeal to the text itself or by assembling more detailed descriptions of the contexts in which the text was composed.

In such cases, comparison provides a means of systematically weighing rival accounts of the background problems that cause political ideas. The key issue is that the causal connection between the background problem to which a text responds and the ideas contained within the text cannot be directly observed. Logically, any causal assertion entails a corresponding counterfactual claim. Asserting, for example, that the advantages George W. Bush enjoyed as an incumbent candidate caused his reelection as president in 2004 entails the claim that were Bush not the incumbent in 2004, he would not have defeated John Kerry. The difficulty—known as the “fundamental problem of causal inference”—is that we cannot directly observe this particular counterfactual: by definition, it never happened. Thus, it is impossible to directly observe the causal connection between Bush’s incumbency and his electoral victory. Instead, the validity of this assertion must be inferred, and it is here that comparison becomes a powerful tool. By examining other presidential elections, including ones that did not involve incumbent candidates, we approximate an observation of the counterfactual. If we also examine additional presidential elections that did involve an incumbent candidate, but where other contextual factors to which alternative theories would attribute Bush’s victory—an ongoing war, an improving economy—differed from 2004, we can increase confidence in our inference (King, Keohane, and Verba Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994, 75–79).

In reconstructing the background problems that influence political ideas, a similar problem arises: we wish to argue that some subset of the ideas articulated by a given author can be explained by reference to the particular configuration of institutional and institutional contexts occupied by that thinker. Equally, but counterfactually, we wish to argue that had the author in question encountered a different configuration of institutional and intellectual contexts, he or she would have had different ideas or no ideas at all. However, we cannot directly observe the author’s encounter with a different background problem, because it never happened. Thus, we approximate such an encounter by comparing our author to others, who did encounter different background problems, and ask how their ideas varied as a result. If we find a systematic pattern of correlations, wherein similar configurations of institutional and intellectual contexts are associated with similar political ideas, and dissimilar configurations with dissimilar ideas, we will have made a compelling, if not indefeasible, case for the explanation we have offered for the ideas under examination.

A key issue in using comparisons for causal inference or reconstructing background problems is properly selecting cases to compare. The idea is to isolate the factors we want to suggest are important aspects of the background problem by controlling for the other factors that alternative explanations suggest are more important. How is this done? John Stuart Mill ([1843] 1974, 388) described what remains the basic logic of the comparative method, offering two basic approaches, which he called the “method of agreement” and the “method of difference.” The method of agreement depends on selecting cases for comparison that are as different as possible in all possibly important respects, except that they share both the outcome that is to be explained and the factor that explains the outcome. As Mill noted, “If two or more instances of the phenomenon under investigation have only one circumstance in common, the circumstance in which alone all the instances agree, is the cause (or effect) of the given phenomenon” (390). The method of difference, by contrast, depends on selecting cases for comparison that are as similar as possible in all possibly important respects, except in the sense that the outcome we wish to explain appears in some cases and not in others, along with the factor that explains the outcome. As Mill put it: “If an instance in which the phenomenon under investigation occurs, and an instance in which it does not occur, have every circumstance in common save one, that one occurring only in the former; the circumstance in which alone the two instances differ, is the effect, or the cause, or an indispensable part of the cause, of the phenomenon” (391). Taken alone, the method of difference is more powerful than the method of agreement, because it is less likely to produce inferences biased by the omission of variables, but both methods offer advantages, and they can be combined to compensate for their respective weaknesses (Geddes Reference Geddes1990; Skocpol and Somers Reference Skocpol and Somers1980, 183). Additional elaborations are possible that reduce the number and implausibility of the assumptions required to apply Mill’s methods to social-scientific questions (Ragin Reference Ragin1987).

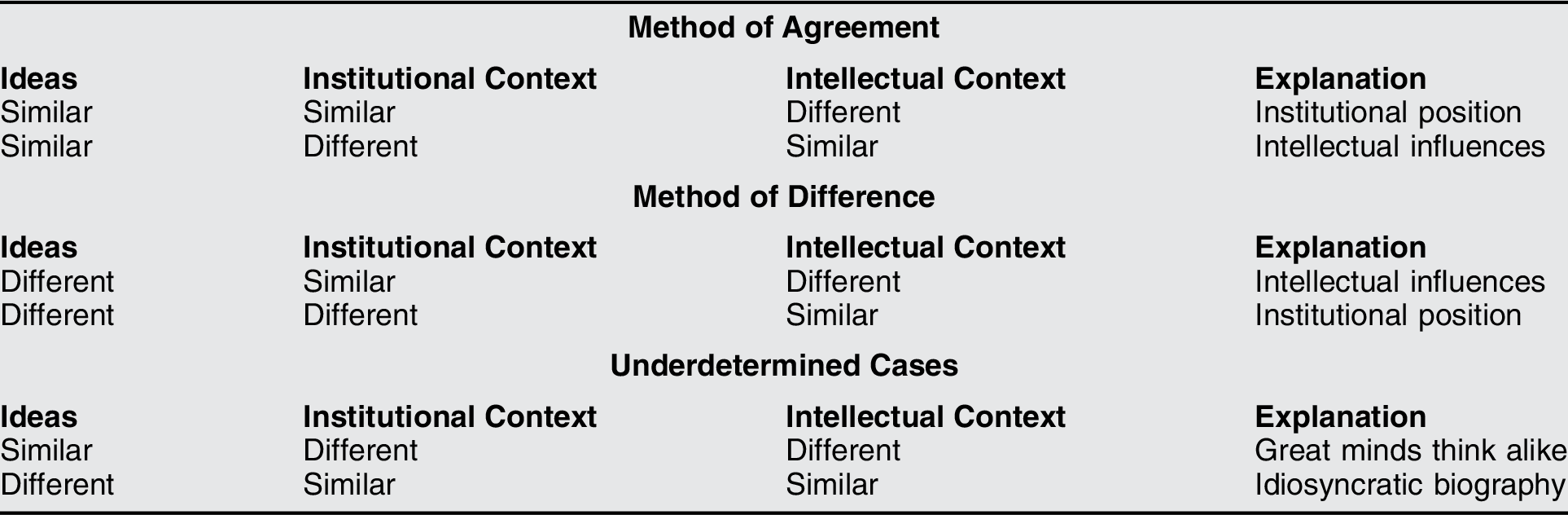

Above, I argued that political ideas are caused by the background problems their authors encountered and that these background problems are, in turn, products of an interaction between the institutional and intellectual contexts that political thinkers inhabit. This account of the relationship between ideas and contexts can be paired with either the method of agreement or the method of difference to defend proposed explanations of different political thinkers’ ideas (see Table 1). If we hope to show, for example, that some subset of a political thinker’s ideas reflect the institutional context that this author inhabited—that this thinker’s arguments defended existing or proposed institutional arrangements that would benefit a particular class—we could either compare that thinker to other thinkers who had similar ideas and occupied a similar institutional context but a different intellectual context (the method of agreement), or compare that thinker to other thinkers who had different ideas and occupied a different institutional context but a similar intellectual context (the method of difference). Alternatively, if we hope to show that a political thinker’s ideas reflect the influence of an intellectual tradition—that the language and concepts that this thinker adopted inspired or constrained the arguments that he or she made—we could either compare that thinker to other thinkers with similar ideas and who occupied a similar intellectual context but a different institutional context (the method of agreement), or compare that thinker to other thinkers who had different ideas and who occupied different intellectual contexts but similar institutional contexts (the method of difference).

Table 1 Comparative Explanation of Variations in Political Ideas Using the Methods of Agreement and Difference, with Underdetermined Cases.

Arranging cases in this fashion also suggests two kinds of explanations that have been proposed as accounts of ideological variation, but that cannot be systematically supported using the comparative method, because they are cases in which the similarity or difference in ideas is “underdetermined” by the thinkers’ institutional and intellectual contexts. Even here, however, comparisons can still help frame arguments. If we wished to show that a given political thinker thought what they did not as a reaction to the distributional inequalities occasioned by their institutional context and not because of the determinative influence of their intellectual context, but because the ideas they articulated are in and of themselves attractive, perhaps even because they are true, we could compare them to other political thinkers who had similar ideas but who occupied different institutional contexts and different intellectual contexts. If we can demonstrate that equivalences appear even in the absence of these explanatory factors, we would make a strong case that they are the result of “great minds thinking alike.” Alternatively, if we wished to show that a given political thinker’s ideas reflect some idiosyncratic feature of their biography or psychological formation, which is not itself a product of their intellectual or institutional context, we could compare them to other thinkers who had different ideas, despite being situated in similar institutional and intellectual contexts. If the thinker in question proves to be unique even when set against comparisons with closely matched backgrounds, it would be plausible to conclude that some biographical or psychological factor provides the best explanation for their ideas.

These difficult cases suggest two more general reservations concerning the comparative explanation of political ideas. First, although comparisons provide a useful way of framing arguments for particular explanations of ideological variation, they depend on the scholar’s ability to observe and categorize the institutional and intellectual contexts occupied by the thinkers under examination. These categorizations will always be subject to disagreement and open to revision, and in some cases, where the primary source materials necessary to describe a given thinker’s institutional and intellectual contexts are scarce, it may be impossible to categorize thinkers in this way. Thus, the explanations inferred from comparisons must always be regarded as provisional, and in some cases, comparison cannot produce even a provisional explanation. Comparison will never yield definitive certainty regarding the background problem or problems that caused a given idea. Indeed, definitive certainty is a doubtful standard to pursue in the explanation of so complex a social phenomenon as political thinking. But recognizing this limitation should not lead us to despair of the enterprise entirely (Ashcraft Reference Ashcraft1992, 709–11; Skinner Reference Skinner2002, 120–22). Well-constructed comparisons can narrow the range of plausible accounts of background problems by discriminating among inconsistent alternatives, and they can advance our understanding by helping scholars identify what kinds of evidence, if available, would lend further support to their own interpretations.

Second, just as all political thinkers always occupy both an institutional and an intellectual context, all political thinkers are also embodied individuals, with biographies and psychologies that distinguish them from even their closest peers. All political thinkers are also capable of creative insights and subject to unmotivated errors. Thus, as emphasized above, comparisons can only help explain subsets of any given thinker’s ideas and can only explain those incompletely. Even the well-designed comparisons in Table 1 should be supplemented by close reading, philosophical analysis, and individualized biographical or psychological information, if they are to be made convincing. Fundamentally, then, the comparative approach I have proposed is intended to complement and not to supplant other interpretive methods in political theory.

Comparison and Critique

In his classic 1969 article, “Political Theory as a Vocation,” Sheldon Wolin described and denounced behavioral “methodism” in political science, warning that excessive preoccupation with the “refinement of specific techniques” for studying politics would “reinforce an uncritical view of existing political structures,” ultimately making political science “unpolitical.” Behavioralist political scientists presented their methods as neutral “tools” for learning about politics, without acknowledging the limitations that their tools imposed on the kinds of questions that could be asked. Specifically, Wolin argued that methodism foreclosed the ongoing interrogation of theoretical first principles that comprises the true, critical vocation of the political theorist, depriving political science of any ability to inform action that aimed not to describe and manipulate established institutions and behavioral regularities, but to change them (1969, 1062–64).

More recently, some comparative political theorists have raised similar concerns in relation to comparative politics and the comparative method. Fred Dallmayr (Reference Dallmayr1997) observes that, within the dominant theoretical paradigms of comparative politics, western political institutions serve as an ideal against which nonwestern societies are evaluated. Comparative political scientists “assume the stance of a global overseer or universal spectator … assessing the relative proximity or nonproximity of given societies to the established global yardstick,” without questioning the hierarchical international order that their approaches reflect and sustain. Dallmayr argues that comparative political theorists, by contrast, should address themselves to precisely those assumptions, “shun[ning] spectatorial allures and assum[ing] the more modest stance of co-participant in the search for truth” (421–42). Murad Idris (Reference Idris2016) develops a related critique by tracing the origins of the comparative method to early social scientists’ efforts to account for political, economic, and cultural differences that were also invoked to justify European imperial projects. For Idris, these origins indicate that “comparison is not a neutral outside.” The seemingly objective “representations of difference” that make up comparativists’ independent and dependent variables “are not a reflection of the world, but a particular construction of it.” Rather than employing, and reifying, these categories, the comparative political theorist’s critical task is to “rethink how privileged comparisons and scales operate in relation to power and asymmetry” (5–6).

Simplifying somewhat, then, Dallmayr and Idris identify two interrelated ways that using the comparative method could obstruct CPT’s critical vocation. First, the comparative method is genealogically linked to European and North American imperialism and consequently reinforces an uncritical acceptance of Europe and North America’s institutional, economic, and cultural superiority and related entitlements to global hegemony. Second, the comparative method seems to offer a neutral, objective perspective from which political ideas and intellectual traditions can be observed, explained, and assessed, without subjecting the observer’s own commitments to critical scrutiny. Simplifying even further, both points suggest that even if the comparative method could help us learn about unfamiliar political thinkers and traditions of political thought, it would at the same time impede or preclude our learning from them.

Without disputing the genealogy of the comparative method upon which these concerns rest, and without denying what I expressly argued above—that a detached, analytical perspective, which regards ideas as ideologies to be explained rather than as more or less attractive principles to be lived by is a necessary complement to the comparative method—I will suggest that using comparisons to explain political ideas could actually advance CPT’s critical projects, multiplying the kinds of criticisms that comparative political theorists can make and broadening the range of figures on whom they can draw in making these critiques.

Here again, it is useful to consider how the practitioners of different approaches to the history of political thought have conceived of the critical purposes that their studies could serve and how these conceptions have influenced comparative political theorists’ accounts of their own critical projects. Quentin Skinner (Reference Skinner2002) famously insists that political theorists should not expect to find the answers to their problems in the history of political thought. Instead, he argued, we must “learn to do our own thinking for ourselves.” But Skinner allows that intellectual history can serve an important critical purpose in the contemporary world: “the classic texts, especially in moral, social and political theory, can help us to reveal—if we will let them—not the essential sameness, but rather the variety of viable moral assumptions and political commitments.” By improving our understanding of texts written long ago, we become better attuned to “the extent to which those features of our own arrangements which we may be disposed to accept as ‘timeless’ truths may be little more than contingencies of our local history and social structure” (88–89; see also Lane Reference Lane2012).

Similarly, comparative political theorists argue that engagement with East and South Asian, Islamic, and African political thought will reveal the contingency and provincialism of the putatively universal principles that are taken for granted within the European and North American intellectual tradition. Jenco (2014, 660) locates CPT’s critical edge in the prospect that the terms in which nonwestern political thinkers think “may eventually come to displace existing criteria for understanding and evaluating what it is we think we are doing” when we do political theory. Similarly, Godrej (2009, 99) asserts that the study of nonwestern ideas promises a “fundamental reframing of questions, and a reconstitution of premises about knowledge production and organization.” For Jenco and Godrej, then, CPT forces a deep reconsideration not only of our substantive commitments—concerning the good life, the best regime, the nature of justice, and so on—but also our very ideas about what it means to think about politics.

This is a radical project, but it also imposes limitations on which political thinkers and intellectual traditions can be productively studied by comparative political theorists and thus on the kinds of critiques that comparative political theorists can use their studies to make. As Andrew March (2009, 552) has argued, to perform its critical purpose, CPT must be dedicated to the study of “distinct, autonomous modes of reasoning” which are in some sense “seal[ed] … off from us,” departing from first principles and developing according to procedures that are distinctive enough to reveal the particularity and contingency of the western canon’s universalist pretensions. The exemplary cases, for March, are intellectuals who have described the political implications of religious doctrines outside the Judeo-Christian spectrum that grounds most of the western canon. To put the point in the terms of the framework developed above, CPT accomplishes its critical purposes by examining texts that are different because of the different intellectual contexts in which they were produced. Improving our understanding of these ideas forces us to acknowledge that the ways that western political theorists are accustomed to thinking about politics are not the only ways in which one can think about politics.

Although this approach opens the way for political theorists to study an enormous range of fascinating intellectual traditions, it also underestimates the critical insights to be gleaned from political thinkers who occupied intellectual contexts similar to those occupied by the leading lights of the western canon, but whose institutional contexts caused them to make unfamiliar arguments with familiar concepts and languages. Latin American political thought provides an excellent illustration of this problem, as scholars who have grappled with the difficulty of fitting Latin American ideas into the critical framework that CPT offers have noticed. In her 2013 study of the Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui, Katherine Gordy observes that although Mariátegui used Marxist-Leninist concepts and terminology in his writings, he “fundamentally undermined some of Marxism’s most basic temporal and spatial assumptions by suggesting that the vestiges of Incan communism in Peru should be used in the struggle for socialism rather than dismissed as relics of the past” (358). In this sense, Mariátegui resembles many of his Latin American and Caribbean compatriots, who thought and wrote in concepts and languages shared with European intellectual traditions, from Thomism and classical republicanism to liberalism and Marxism, but who addressed background problems partially constituted by the distinctive institutional contexts that characterized Spanish, French, and Portuguese colonies and postcolonies, slave states, and cimarrón societies and who consequently advanced very different arguments from those of their intellectual forebears (Getachew Reference Getachew2016; Hale Reference Hale1968; Hooker Reference Hooker2017; James [Reference James1938] 1989; Roberts Reference Roberts2015; Simon Reference Simon2012; Reference Simon2017; von Vacano 2012).

Comparisons structured according to the method described above would allow comparative political theorists to draw critical insights from these thinkers by systematically demonstrating the ways in which institutional contexts shape political ideas. For example, during the latter half of the nineteenth century, political thinkers in the United States defended their country’s increasingly interventionist foreign policy in Central America and the Caribbean using a language and a set of concepts developed during the American independence movement, arguing that cross-continental expansion and the creation of overseas protectorates would help preserve the hemisphere’s independence from Europe, strengthen its republican political institutions, and hasten its economic development (Hendrickson Reference Hendrickson2009; Lewis Reference Lewis1998; Sexton Reference Sexton2011; Simon Reference Simon2014; Reference Simon, Arato, Cohen and Busekist2018). However, in the same period, several important Latin American political thinkers drew on the same intellectual tradition to argue, contrarily, that the growing power of the United States, left unchecked, presented an imminent threat to their nations’ independence, an impediment to the consolidation of democratic and liberal institutions in the region, and a significant cause of economic underdevelopment (de la Reza 2009; Gobat Reference Gobat2013; Grandin Reference Grandin2006; Scarfi Reference Scarfi2016). A comparison of these North and Latin American thinkers, who shared a common intellectual context, could demonstrate that the Americas’ ideological divergence during this period was attributable to the distinctive institutional positions that U.S-American and Latin American political thinkers occupied. In this sense, it would suggest that the universal advantages that U.S.-American political thinkers claimed for the institutions they defended actually served a very partial set of interests. More generally, then, comparison provides a rigorous means of demonstrating the limitations that not only intellectual contexts but also institutional contexts impose on political thinking.

The comparative method could also help comparative political theorists move beyond deconstructive critiques by identifying not only the instances in which European and North American thinkers’ universalist pretensions should be questioned but also those in which Asian, African, and Latin American thinkers’ universalist claims should be taken seriously. Ashcraft (Reference Ashcraft1980) has argued that recognizing that the political thinkers we study were “as deeply immersed in their [own] times, political battles, and ideological struggles as we are” in ours does not reduce their ideas to historical curiosities, but rather “establish[es] a bridge between the historical emergence and development of an ideological perspective…and its present role as a theoretical response to the political problems of our society” (702–3). That is to say, using comparisons to learn about ideas and intellectual traditions can actually help us learn from them. At present, CPT’s critical capacities are limited by its susceptibility to the same relativism that follows from Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics or Skinner’s contextual approach to the history of ideas. These approaches, though effective in demonstrating that all political ideas are contingent on the contexts in which they appear, cannot furnish any ground for preferring some contexts to others as sources of critical insights relevant to the contemporary world. By contrast, the modified Marxian account of political ideas as ideologies developed earlier, coupled with the comparative method, can supply these grounds.

In the passage from The German Ideology cited above, Marx ([1845–46] 1973) observed that “each new class which puts itself in the place of one ruling before it is compelled, merely in order to carry through its aim, to represent its interest as the common interest of all the members of society.” Here, as I argued earlier, Marx seems to share comparative political theorists’ critical outlook on universalist political ideas, insisting that universalism always masks partial class interests. Marx, however, then argued that insurgent classes actually have a better claim on universalism than the ruling classes they aim to displace, “because…[their] interest[s] really [are] more connected with the common interest of all other non-ruling classes.” Indeed, he suggested that “every new class… achieves its hegemony only on a broader basis than that of the class ruling previously” and that, consequently, each new insurgency “in its turn, aims at a more decided and radical negation of the previous conditions of society than could all previous classes which sought to rule.” (174). The broad basis of oppressed classes that insurgents assemble to displace the status quo affords insurgent political thinkers a unique perspective, from which the contradictions present in ruling ideas and institutions are apparent and can be corrected. Revolutionary ideologies, then, though still perhaps marred by their own contradictions, come closer to a true depiction of reality than the status-quoist ideologies they seek to supplant. For Marx, because of the ever-wider basis of the revolutionary classes that challenge the status quo over time, there is progress toward what Dallmayr (2004, 253) calls “a more genuine universalism” in the history of ideas.

The Hungarian Marxist Georg Lukács ([1923] 1971) developed this insight, arguing that capitalist relations of production endowed industrial laborers with a privileged “standpoint,” which permitted political thinkers engaged in the labor movement to produce an “objective understanding of the nature of society,” free from the mystifying ideologies of the bourgeois ruling class (149). The social theorist W. E. B. Du Bois makes a parallel claim in The Souls of Black Folk ([1903] 2007, 3), suggesting that pervasive racial oppression had “gifted” black Americans “with second-sight in this American world”—a “double-consciousness” or capacity to see from multiple perspectives that could simultaneously hinder true self-consciousness and disclose truths that white Americans did not grasp as sharply (see also Gooding-Williams Reference Gooding-Williams2009, 77–83). The same insight runs through “standpoint feminism,” which built an account of the epistemological privilege that women acquired in patriarchal societies on Marxian foundations (Hartsock Reference Hartsock, Harding and Mintinkka1983; Hekman Reference Hekman1997; Collins Reference Collins2000, 3–24). For Nancy Hartsock (1983, 284), “women’s lives make available a particular and privileged vantage point on male supremacy.” The truth of feminists’ critical characterizations of the existing institutions that perpetuate patriarchy derives precisely from the disadvantage that women suffer while living under those institutions.

These Marxian accounts of the privileged epistemological standpoint that institutional disadvantage affords members of the working-class, African Americans, and women in capitalist, white supremacist, and patriarchal societies converge with an important critical intuition expressed in the CPT literature: political theorists stand to learn something important from political thinkers and intellectual traditions that are not featured in the traditional western canon. The comparative method described in this article can clarify and vindicate this intuition, defending the underlying claim concerning the close connection between political ideas and the institutional context in which they emerge, and identifying exactly what aspects of a given thinker’s thoughts are attributable to the unique perspective afforded by that author’s institutional position. In this way, comparison can direct us to the ideas that will move us toward a more genuine universalism.