Rather than dying with a bang, democracies are now more prone to fade through a slow and weakening whimper (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). Over the last decade, our understanding of autocratization has progressed remarkably (Cassani and Tomini Reference Cassani and Tomini2020; Cianetti and Hanley Reference Cianetti and Hanley2021; Doyle Reference Doyle2020; Little and Meng Reference Little and Meng2024; Pelke and Croissant Reference Pelke and Croissant2021; Wunsch and Blanchard Reference Wunsch and Blanchard2023), with recent contributions bringing the debate full circle by highlighting how to resist it (Cleary and Öztürk Reference Cleary and Öztürk2022; Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022), and by identifying the factors that have underpinned democratic resilience worldwide (Brownlee and Miao Reference Brownlee and Miao2022; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2023). At the same time, we have accumulated a considerable amount of knowledge on how regimes vary within countries (Gervasoni Reference Gervasoni2018; Gibson Reference Gibson2012; Giraudy Reference Giraudy2015). We now know that subnational regimes are not simply a function of national ones. However, with few exceptions (Grumbach Reference Grumbach2022), these two research strands have not engaged in a thorough dialogue with one another. As such, the territorial dimension of autocratization and of contemporary regime change patterns remains underexplored.

This gap is surprising given the salience that territorial, subnational politics have had for recent national democratic outcomes both in developed and developing countries. For example, in the United States, the subnational arena has been both a blessing and a curse for democratic politics. On one hand, governors and mayors—along with state and local bureaucracies—resisted President Trump on issues such as healthcare and migration (Greer et al. Reference Greer, Dubin, Falkenbach, Jarman and Trump2023; Reich Reference Reich2018). On the other hand, over the last decade the subnational arena in the United States has truly become a laboratory of backsliding politics (Grumbach Reference Grumbach2023).

In Europe, especially in Germany and France, the debate has centred on different local reactions to migration (Manatschal, Wisthaler, and Zuber Reference Manatschal, Wisthaler and Zuber2020; Van der Gaag and Van Wissen Reference Van der Gaag and Van Wissen2001), and on the threatening backlash posed by the increasing electoral success of populist and illiberal far-right parties (Georgiadou, Rori, and Roumanias Reference Georgiadou, Rori and Roumanias2018; Jakli and Stenberg Reference Jakli and Stenberg2021). For its part, research on Brazil, Colombia, and other Latin American cases has shown that, in the aftermath of the Third Wave (Huntington Reference Huntington1991), political decentralization has catalysed democratic heterogeneity at the local level (Behrend and Whitehead Reference Behrend and Whitehead2016b; Harbers and Steele Reference Harbers and Steele2020; Herrmann Reference Herrmann2017). In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and in Asia, Turkey’s Recep T. Erdoğan and India’s Narendra Modi have brought about an encroachment on the subnational arena (Begadze Reference Begadze2022; Mukherji Reference Mukherji2020; Sharma and Swenden Reference Sharma and Swenden2018). Finally, the Russian experience vividly shows how Putin’s (un)subtle power grab involved the dismantling of democracy at the national and the subnational level (Golosov Reference Golosov2018; Moses Reference Moses2015).

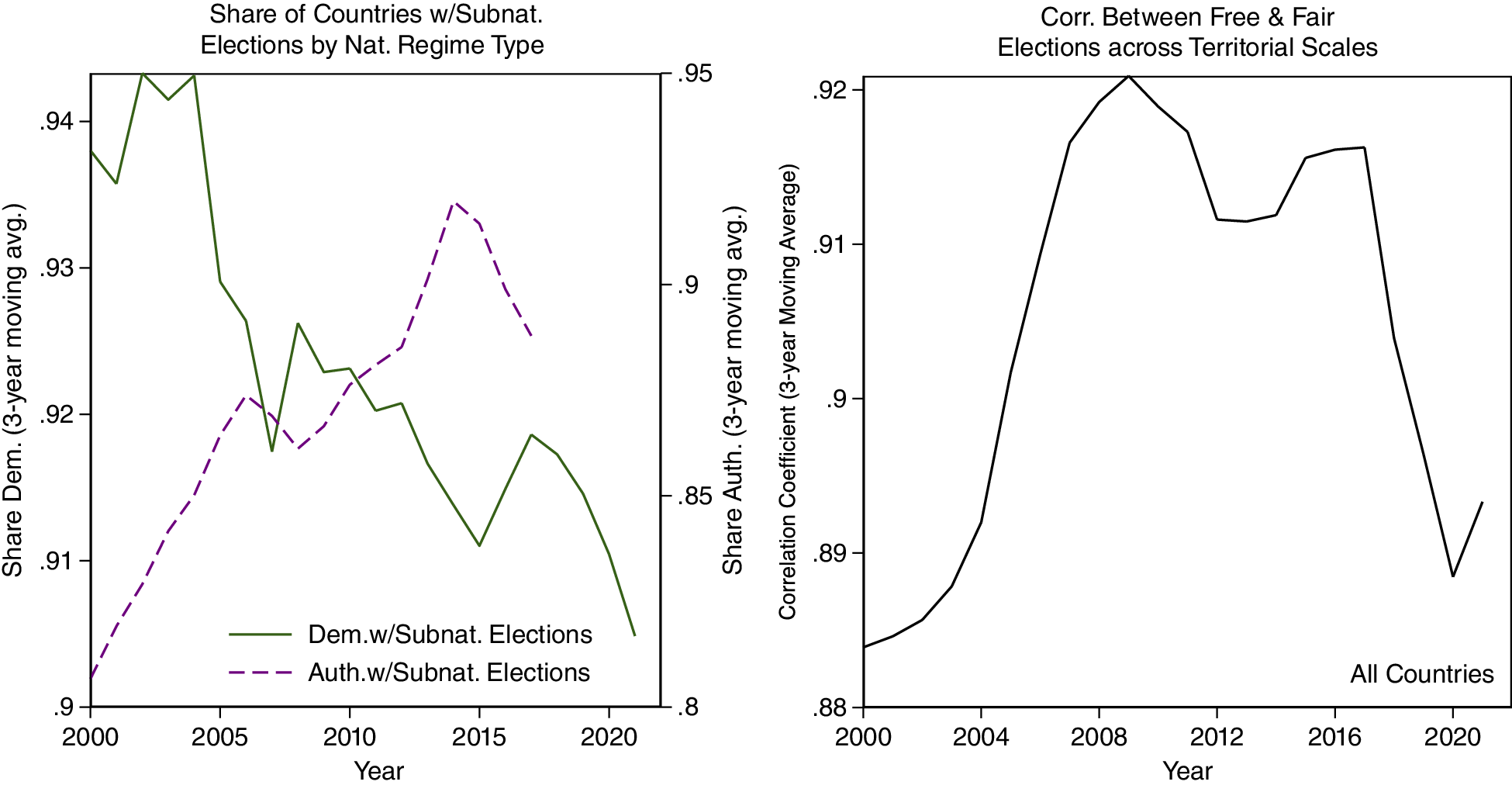

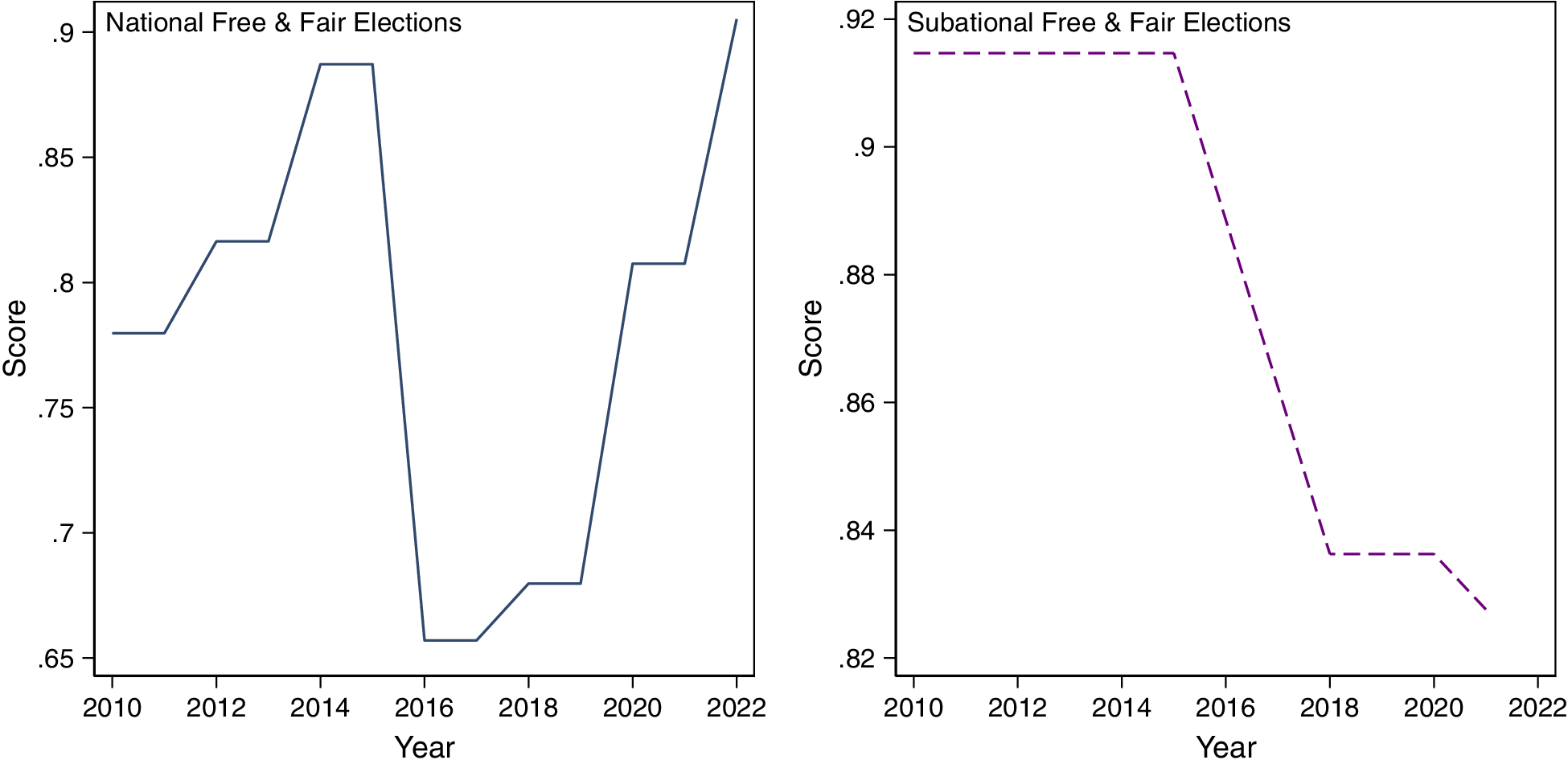

If autocratization is any move away from full democracyFootnote 1 (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019), overlooking the territorial dimension of this erosion is problematic because, as the graph on the left side of figure 1 shows, over the last two decades, the share of democracies (countries with a Polity score of 6 or higher) that hold subnational elections decreased from 94% in 2002 to 90% in 2022 (solid green line). While a 4% drop may appear small, at best, it indicates a marked trend towards electoral centralization, and at worse, it potentially signals a total of 51 discrete instances of subnational electoral breakdown. At the same time, subnational elections have become more common in authoritarian countries (Polity score≤5), rising from 78% in 1990, to 87% in 2019 (dashed purple line). Subnational regimes are changing in both democratic and authoritarian national polities.Footnote 2

Figure 1 The puzzling territorial dimension of autocratization and contemporary regime change

Notes: Built by the author using V-Dem data (v13). The graph on the left uses a Polity Score>5 to classify countries as either democratic or authoritarian, and the binary V-Dem item v2elffelrbin_ord, which indicates whether subnational elections were held in any given country-year spell. The graph on the right looks at the yearly, global correlation between free and fair national (v2elfrfair) and subnational (v2elffelr) elections. Except for the Polity score, all other variables have been standardised between 0 and 1.

As the graph on the right of figure 1 indicates, overlooking the territorial dimension of contemporary regime change is also problematic because the correlation between clean (free and fair) national and clean subnational elections has recently dropped. While it was still a strong and positive correlation as of 2022 (Pearson Coefficient=0.89), the association of clean elections across multiple levels of governance has reverted to a value last observed in the early 2000s. Taken together, these graphs suggest not only that subnational politics have been an important part of the contemporary patterns of regime change, but also that regimes across territorial levels increasingly move in separate directions.

Indeed, recent discussions (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2022; Cianetti and Hanley Reference Cianetti and Hanley2021) have suggested that a more comprehensive diagnosis of autocratization and contemporary regime change dynamics would need to unpack what transpires inside countries. In this article, I take a step forward in this direction by bridging the agendas on autocratization and subnational regimes. To do so, I analyse the democratic gap that has emerged across national and subnational governmental tiers. I ask: How can we conceptualize and empirically observe contemporary episodes of multilevel autocratization and regime change more broadly?

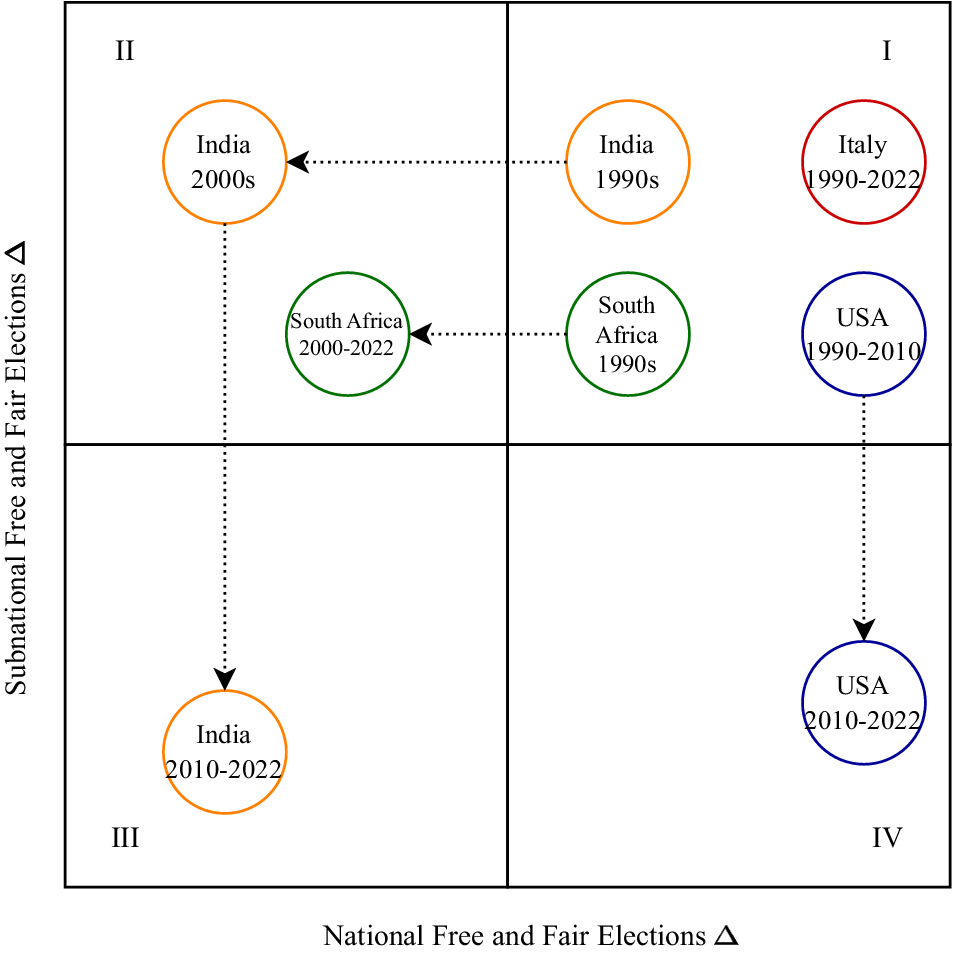

Taking territoriality seriously, I focus on the divide between the national and the subnational tiers. When both governmental spheres move in the same direction, regime change is territorially coupled. However, extending Ding and Slater’s (Reference Ding and Slater2021) rationale, I argue that when democratic traits advance (erode) in one territorial level, but erode (advance) in another, we observe episodes of multilevel regime decoupling (MRD). In this paper, I show that instances of MRD are increasing. They represented 20% of cases in the 1990s, 29% in the first decade of the 2000s, and from 2010 to 2022, multilevel regime decoupling accounted for 43% of cases in a global sample. Based on the estimates presented here, over the last decade, four out of every ten episodes of regime change have been territorially decoupled.

Rather than causal, the main objectives and the main contributions of this piece are conceptual and descriptive. Conceptually, I show that multilevel regime decoupling is a broader, more abstract concept (Sartori Reference Sartori1970), than Gibson’s (Reference Gibson2005, Reference Gibson2012) foundational “regime juxtaposition.” Descriptively, in this paper I shed light on a previously unobserved phenomenon, by relying on observational data and known theories of (sub)national regime change. I contribute to the discussion by showing that MRD is not only a contemporary global phenomenon, but also an identifiable experience across world regions and within specific country cases. As such, to illustrate my quantitative findings, I look at the United States and the South African experiences as instances of decoupled change, and I explore Italy and India as cases of territorially coupled dynamics.

While articulating a full causal account of multilevel decoupling is outside the scope of this piece, preliminary regression analyses suggest that state strength, regional autonomy, and electoral management bodies influence but do not determine MRD. The insights provided by my descriptive cases (Gerring Reference Gerring2017; Soifer Reference Soifer2020) further highlight that courts play a pivotal role in setting the territorial domain in which politics then unfolds. Courts, the case evidence suggests, have been a key institutional actor in triggering or enabling MRD. While this preliminary conclusion falls in line with recent scholarship highlighting the pivotal role of the judiciary in strengthening (or curtailing) democratic outcomes (Daly Reference Daly2017; González-Ocantos Reference González-Ocantos2016; Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2015), in the conclusion I additionally discuss the relevance of parties and sequencing, underscoring that an actor-based approach is perhaps best suited to account for MRD. In so doing, I lay the building blocks for future theorization and research on the documented varieties of regime (de)coupling. By showing that regimes across territorial levels increasingly move in separate directions, I make the case that research on this topic matters not only for future scholarly literature, but also for policy and advocacy work. Academic assessments and democracy promotion efforts that look at country-level change only will be gradually less informative and gradually less impactful in enhancing citizens’ experiences on the ground.

The paper proceeds as follows: In the next section I elaborate further on the concept of multilevel (de)coupling, outlining the logically plausible regime change paths we can observe, and highlighting how MRD builds on and departs from existing literature. I then discuss my analytical approach and my case selection strategy. Using data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem v13) project (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell and Altman2023b), I present global patterns of MRD for the 1990–2022 period. I then use Fidalgo’s (Reference Fidalgo2021) and Sandoval’s (Reference Sandoval2023) measures of subnational democracy to buttress the robustness of my descriptive findings. My quantitative examination concludes with a set of regression analyses that, following McMann et al. (Reference McMann, Maguire, Gerring, Coppedge and Lindberg2021), examine the influence of potential structural, institutional and territorial explanatory factors.

Looking at cases, I then discuss recent changes in Italy and India as illustrative examples of coupled regime change. In the former, free and fair democratic elections advanced at the national and the subnational level. In the later, they have considerably eroded across territorial scales. Afterwards, I explore South Africa and the United States as instances of multilevel decoupling. In South Africa, electoral democracy has eroded in the national arena, but it has moderately improved in the subnational one. In the United States, we observe the reverse pattern, with the national arena making a recovery after the Trump presidency, but with increasing electoral constraints at the subnational level. In the concluding remarks, I briefly compare the evidence provided by both the quantitative assessment and the cases to discuss potential explanatory factors for this phenomenon, and to underscore a few implications for the research agenda on multilevel regime change.

Unpacking Multilevel Regime Decoupling

While it remains true that the difficulties in identifying autocratization are rooted in measurement strategies and in how democracy is conceptualized (Jee, Lueders, and Myrick Reference Jee, Lueders and Myrick2022), a territorial lens pushes this critique further by highlighting that our understanding of movements towards and away from democracy is shaped also by the chosen level of analysis. Democracy is neither linear nor unidimensional, not only because quantitative differences might diverge from qualitative ones (Collier and Levitsky Reference Collier and Levitsky1997), and not only because the electoral or procedural domain might differ from the liberal one (Ding and Slater Reference Ding and Slater2021). Democracy is also not unidimensional because these types of changes can occur at the national level and across subnational units (SUs) inside countries. That is, regimes do not necessarily change consistently across different territorial levels.

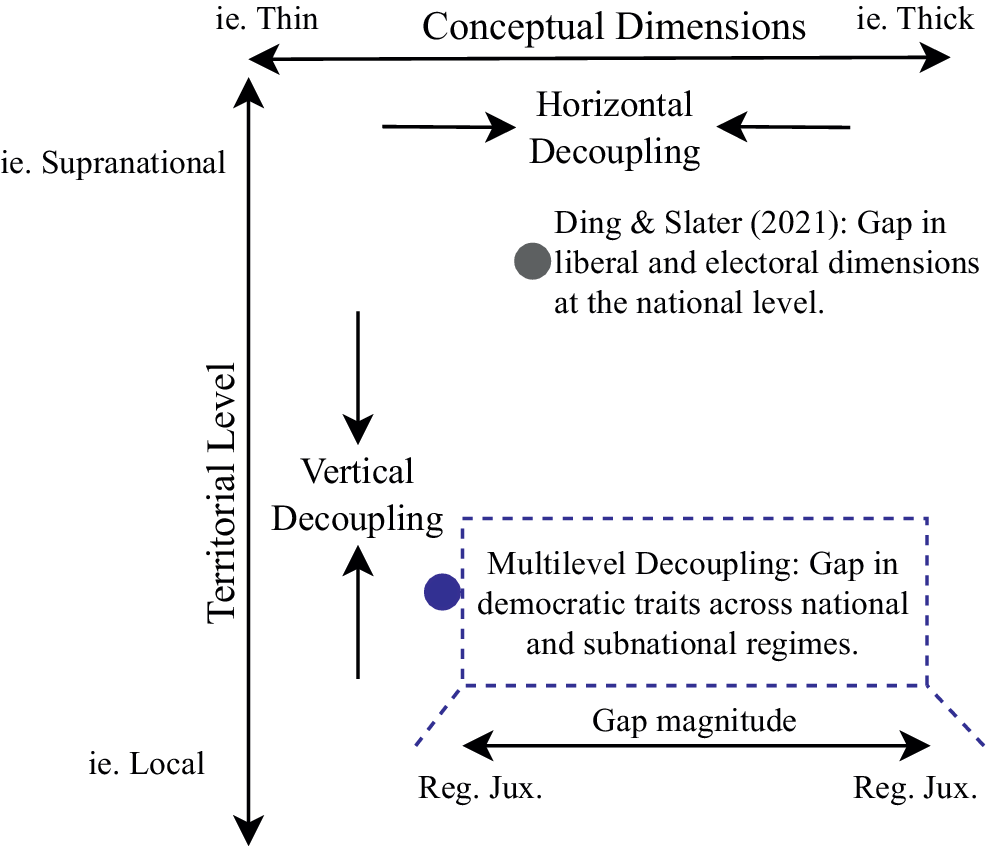

As seen in figure 2, there are at least two relevant varieties of regime decoupling. There is the type of horizontal decoupling described by Ding and Slater (Reference Ding and Slater2021), in which distinct conceptual dimensions of democracy diverge along the same territorial level, and there is also the type of vertical decoupling, in which democratic changes move in diverging directions across different territorial scales. As other forms of vertical decoupling could, for example, explore the increase in democratic disparities between regional or supranational spaces, here I understand multilevel decoupling to be a subtype of vertical decoupling, placing emphasis on the divergence between national and subnational democratic movements inside individual countries.

Figure 2 Varieties of regime decoupling

A territorial lens also lends credence to Waldner and Lust (Reference Waldner and Lust2018), who contend that we can observe subnational gains (losses) in both democratic and authoritarian national settings. In principle, one could observe and measure multilevel change across the liberal and electoral dimensions of democracy, and even across more complex domains which have political freedom and self-determination at their core (Jee, Lueders, and Myrick Reference Jee, Lueders and Myrick2022; Munck Reference Munck2016). However, in light of recent warnings against territorial conflation (Sandoval Reference Sandoval2023) (i.e., that thick dimensions of democracy, such as the liberal one, do not solely belong to the territorial boundaries of subnational units), in this piece I adopt a continuous understanding of political regimes and focus on the electoral, procedural dimension of democracy (Dahl Reference Dahl1971).

In sum, free and fair elections are here the minimal threshold for democracy. Ad minimum, free and fair elections are those in which—before, during, and after polling day (Elklit and Svensson Reference Elklit and Svensson1997)—“coercion is comparatively uncommon” (Dahl Reference Dahl2005; Schmitter and Karl Reference Schmitter and Karl1991). Although not a sufficient condition, free and fair elections are certainly a necessary one for democracy to exist at both the national and the subnational level. As we will see later, the proxies for the electoral dimension of democracy are also more comparable once they travel down the territorial scale, allowing for a conceptually transparent multilevel analysis.

Even under this minimal threshold, autocratization may not lead to the uniform erosion of democracy across all territorial units. More generally, as figure 1 indicated earlier, regimes at the national and the subnational levels increasingly change in diverging directions. My contention is that we should be especially aware of multilevel decoupling, the growing gap that emerges when regimes move in opposite directions across territorial scales. As highlighted in the introduction, MRD matters to academic and policy-oriented discussions on democracy. On the academic front, I echo previous scholars by emphasizing that a territorial lens enhances our ability to bring our conceptual, theoretical, and empirical assessments closer to the ideal principles underlying democracy and to the lived experiences of individuals (Giraudy, Moncada, and Snyder Reference Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019; Giraudy and Pribble Reference Giraudy and Pribble2019; Snyder Reference Snyder2001). I contribute by underscoring that this also matters if policy implementation, institutional design, and democracy promotion efforts are to remain impactful in enhancing citizens’ experiences on the ground.

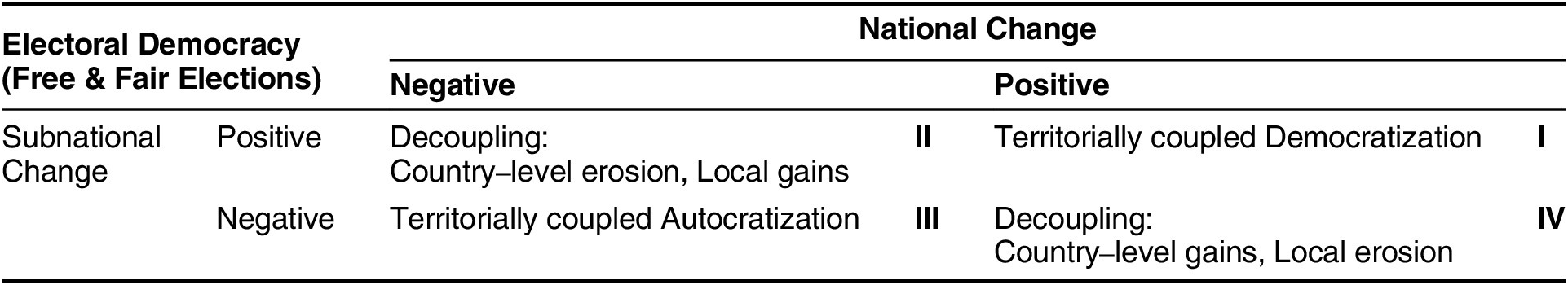

Table 1 shows a two-by-two table with the possible configurations when observing changes in the level of (electoral) democracy across territorial scales. Each quadrant is labelled counterclockwise using roman numerals. In this sense, quadrants I and III correspond to coupled movement towards (QI) and coupled movements away from democracy (QIII). In these cases, democratic gains or democratic losses are consistent across territorial levels. Quadrants II and IV correspond to multilevel decoupled change. In quadrant II we observe instances with democratic gains at the subnational level and losses at the national one. Quadrant IV locates instances with the inverse pattern.Footnote 3 By assuming that democratization and autocratization are always territorially coupled, the extant scholarship has overlooked quadrants II and IV. While these are my main zones of theoretical interest, to contrast coupled and decoupled change, and to showcase what a territorial lens brings to the analysis of regime change, here it is also illustrative to look at cases in quadrants I and III.

Table 1 Conceptualizing multilevel regime decoupling

Multilevel regime decoupling (MRD) builds on and extends the rationale of Gibson’s (Reference Gibson2005, Reference Gibson2012) foundational “regime juxtaposition” (RJ). For Gibson, RJ signals “the coexistence of a national democratic government with authoritarian subnational governments” (Gibson Reference Gibson2012, 148). As such, a first key difference between MRD and RJ is that the latter is unidirectional, describing instances under quadrant IV only, but leaving aside cases located in quadrant II. A second key distinction is that Gibson’s RJ relies on a crisp or binary understanding of political regimes, consequently eschewing hybridity (Gibson Reference Gibson2012, 14) and voiding the concept’s ability to capture more gradual or subtle changes. As shown on the bottom right side of figure 2, at the extremes, multilevel regime decoupling could—in principle—lead to the juxtaposition of regimes in either direction (either subnational autocracies inside nationally democratic polities or subnational democracies inside authoritarian national regimes). MRD is better suited to capture cases and dynamics of gradual political change. A third related and important difference is that juxtaposition alludes to a fixed state of affairs: national and subnational regimes that stand in sharp contrast to each other. (De)coupling alludes more explicitly to a process, and it thus better accommodates the fact that regimes can move in converging or diverging directions.

Multilevel regime decoupling also builds on insights from classic contributions by Gervasoni (Reference Gervasoni2010, Reference Gervasoni2018), Giraudy (Reference Giraudy2015), as well as by Behrend and Whitehead (Reference Behrend and Whitehead2016a). It departs from this extant scholarship in that, for these authors (Gibson included), the focus and the key dependent variable has been how provinces or specific subnational units within countries become more or less democratic. Intergovernmental relations and other national factors might impact this outcome, but the aim of these studies has been to account for regime change in a single territorial level: the subnational level. Similarly, MRD distinguishes itself from the recent explorations and efforts to better understand the unevenness of democracy across the subnational arena (Giraudy and Pribble Reference Giraudy and Pribble2019; McMann et al. Reference McMann, Maguire, Gerring, Coppedge and Lindberg2021).

In sum, MRD draws attention to the joint (dis)harmonious movement of national and subnational political regimes. Hence, while debates on subnational democracy and subnational authoritarianism may have implicitly or indirectly suggested the possibility of decoupling, to the best of my knowledge, this is the first attempt to explicitly conceptualize the phenomena and, using the tools described in the next section, the first paper to empirically assess its realization.

Data and Empirical Approach

The core quantitative results of this paper are based on data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project (v13). Although this precludes comparing the trajectories of individual subnational units (SUs), using V-Dem data enhances the consistency of comparisons across time and space. V-Dem variables are underpinned by a similar methodology, strengthening our ability to focus on contrasting territorial levels within and across countries through time. Nonetheless, thanks to the increased availability of democracy measures at the subnational level (Gervasoni Reference Gervasoni2018; Giraudy Reference Giraudy2015; Grumbach Reference Grumbach2022; Harbers, Bartman, and van Wingerden Reference Harbers, Bartman and van Wingerden2019), as I discuss later, I am also able to use two alternative proxies to buttress my results (Fidalgo Reference Fidalgo2021; Sandoval Reference Sandoval2023; Sandoval Reference Sandoval2024).

In terms of V-Dem data, I specifically use two items: To capture electoral democracy at the national level, I use the v2elfrfair variable, which asks country experts the following question: “Taking all aspects of the pre-election period, election day, and the post-election process into account, would you consider this national election to be free and fair?” (V-Dem Codebook (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman and Bernhard2023a), emphasis added). This is preferred over the traditional polyarchy measure (v2x_polyarchy) or the clean election index (v2xel_frefair) because, as I indicate next, it relates more directly to the item for which we have V-Dem data at the subnational level. To capture electoral democracy at the subnational level, I use the v2elffelr variable, which asks country experts: “Taking all aspects of the pre-election period, election day, and the post-election process into account, would you consider subnational elections to be free and fair on average?” (V-Dem Codebook, emphasis added).

Importantly, the questions for both items offer country experts the exact same phrasing along the 5-point Likert scale rating used to register their answers. At the lower end, the option reads “The elections were fundamentally flawed, and the official results had little if anything to do with the ‘will of the people’”; the mid-way option reads “There was substantial competition and freedom of participation but there were also significant irregularities. It is hard to determine whether the irregularities affected the outcome or not”; and the highest score possible on the Likert scale reads “There was some amount of human error and logistical restrictions, but these were largely unintentional and without significant consequences.”Footnote 4 This clarification is relevant as it strengthens the comparability of the scores and elucidates the exact way in which these items proxy for the electoral dimension of democracy across territorial scales.

All V-Dem items are standardized between 0 and 1. Given that a territorial lens concedes that we can observe subnational democratic gains in national authoritarian settings, I include data from 181 countries.Footnote 5 Considering that my theoretical interest lies in exploring the territorial dimension of contemporary patterns of autocratization and regime change, following Ding and Slater (Reference Ding and Slater2021), I focus my global quantitative analysis on three periods: 1990–2000, 2000–2010, and 2010–2022.

Here, there are three important caveats to highlight. First, the V-Dem item for free and fair subnational elections (v2elffelr) does not neatly distinguish between the subnational jurisdictions being assessed. For example, in federal countries this means that provinces and municipalities are likely grouped under the “subnational” label. In unitary countries, this is also true for departments or municipalities. That is, we cannot disaggregate these items by specific governmental tiers. However, this is not particularly problematic as my main theoretical focus is on exploring whether—around the world—recent episodes of national regime transformation have implied dissonant (or concordant) subnational changes within countries. The selected V-Dem items are well suited for that purpose.

Second, it is likely that by focusing only on the electoral dimension of democracy, I am underestimating change. Looking at variations on the extent to which elections are free and fair might obscure modifications on the role of norms, rights, media plurality, and other formal and informal institutions that shape democratic politics within countries. The silver lining is that this underestimation cuts both ways, meaning I am likely to underestimate both democratic gains and democratic losses.

Third, while methodologically and conceptually sound, V-Dem variables are usually highly correlated (Munck and Verkuilen Reference Munck and Verkuilen2002; Boese Reference Boese2019). Indeed, as shown in the introduction, the overall correlation between our two items of interest is remarkably high (Pearson Coefficient=0.89). This means that by design we are less likely to find large differences between the items. It could also mean that as subnational analyses gain salience in political science, the (small) differences capture the growing awareness of the subnational arena among surveyed experts more than “real” discrepancies between national and subnational regimes.

Despite these limitations, these V-Dem items are still the best suited data to identify global instances of multilevel regime (de)coupling. In an effort to address these restrictions I nonetheless adopt three strategies: first, I assess whether the differences found are, on average, significantly different from zero. Second, I draw from Fidalgo’s (Reference Fidalgo2021) ‘Subnational Electoral Democracy Score’ (SEDS) and Sandoval’s (Reference Sandoval2023) ‘Index of Subnational Electoral Democracy’ (ISED),Footnote 6 using the corresponding country-year mean of these indices to replicate the analysis. Third, I examine specific cases, which allows me to descriptively substantiate the insights drawn from these numerical proxies.

As highlighted in the previous section, to the best of my knowledge, there is no existing theory on multilevel regime decoupling, and building a complete theoretical account of a global phenomenon exceeds the scope of a single paper, likely requiring a joint disciplinary effort. Nonetheless, my approach to the topic is primed by regime change studies (Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014; Boix Reference Boix2003; Miller Reference Miller2021; Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991), discussions on democratic institutional design (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999; Linz Reference Linz1990; Power and Gasiorowski Reference Power and Gasiorowski1997; Tsebelis et al. Reference Tsebelis, Thies, Cheibub, Dixon, Bogea and Ganghof2023), the scholarship on federalism (Erk and Swenden Reference Erk and Swenden2010; Gibson Reference Gibson2004; Montero and Samuels Reference Montero and Samuels2004; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2006), and research on multilevel governance (Benz, Broschek, and Lederer Reference Benz, Broschek and Lederer2021; Eaton Reference Eaton2022; Giraudy and Niedzwiecki Reference Giraudy and Niedzwiecki2021; Pazos-Vidal Reference Pazos-Vidal2019). To use a Bayesian heuristic: coming into the analysis, my priors had been shaped by the cumulative knowledge of these academic agendas.

Drawing from this scholarship, and to provide the building blocks for future theory-building conversations, I close the quantitative assessment by presenting the main results of a preliminary set of two-way fixed effects regression analyses that probe how salient structural (i.e., development and state capacity), institutional (i.e., executive format and electoral system), and territorial (i.e., federal versus unitary systems and terrain ruggedness) factors are for MRD. Drawing from a variety of sources, the factors assessed also include Hooghe’s et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Niedzwiecki, Chapman-Osterkatz and Shair-Rosenfield2016) “Regional Authority Index,” as well as Garnett’s (Reference Garnett2019) and Wolf’s (Reference Wolf2014) data on the capacity and the type of electoral management bodies.Footnote 7

Following recent calls for both transparency and rigour in case study and case selection strategies (Koivu and Hinze Reference Koivu and Hinze2017), I outline here my case selection rationale by first clearly stating my goals and my limitations and then describing the case selection procedure. My main goal is descriptive: to illustrate (de)coupled democratic change. Since description is always informed by theory and at the same time aids theorization (as it always involves a degree or a type of inferenceFootnote 8 [Goertz Reference Goertz2012; Mumford and Anjum Reference Mumford and Anjum2013]), my secondary objective is to use the information obtained through this descriptive exercise to highlight explanatory factors that may be relevant for future research. For these reasons, in this piece, my approach to studying cases is nominal (Soss Reference Soss2018) and iterative (Fairfield and Charman Reference Fairfield and Charman2022)—nominal because I use cases to discern and substantiate the meaning of (de)coupling, and iterative because I engage in a dynamic process that moves between theoretical priors, case analysis, and the posterior update of knowledge. As such, in selecting cases, I aimed to maximize informational gains and regional representation, while balancing my previous knowledge, my linguistic abilities, the availability of research and scholarly resources, as well as discussing cases that would allow me to dialogue with the extant literature.

To maintain rigour and account for the objectives and constraints highlighted above, I proceeded as follows: Taking the last temporal period as a starting point (2010–2022), I classified each country according to its corresponding quadrant (QI through QIV). Then, starting with QI (coupled cases of democratization), I looked at the list of potential cases and picked Italy as the case that most closely balanced the trade-offs just discussed. For this quadrant, other potential cases that also partially balanced the criteria included Canada and Colombia. I then moved on to QII (decoupled cases, with subnational gains and national losses) and repeated the procedure selecting South Africa. For this quadrant, other instances could have been Germany, Poland, or Peru. Repeating the procedure for QIII (coupled cases of autocratization) I selected India, while other potential instances could have been Turkey or Guatemala. Finally, for QIV (decoupled cases, with national gains and subnational losses) I selected the United States, although other potential instances in this last quadrant could have been the United Kingdom or Mexico. Italy, South Africa, India, and the United Sates are then descriptive casesFootnote 9 (Gerring Reference Gerring2017) used to exemplify the varieties of multilevel (de)coupled regime change identified earlier.

To abide by the highest standard of multilevel case analysis (Giraudy, Moncada, and Snyder Reference Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019), I aimed to maintain a degree of consistency in the subnational level explored across cases. Nonetheless, given the exploratory nature of the analysis, I also cast a wide net and, when necessary (i.e., South Africa), I highlight third or lower governmental tiers in my examination. Overall, this strategy is more transparent and preferable over selecting deviant or extreme cases. This latter strategy is usually better for discriminating previously identified causes, but it does not necessarily allow researchers to discern them iteratively (Fairfield and Charman Reference Fairfield and Charman2022).

When looking at Italy, South Africa, India, and the United States, I rely on extensive and intensive desk research, drawing on reports and documentation provided by governments, and other national and international organizations. I also draw on secondary historical sources and on extant social and political science literature. I proceed following a “within” case logic and go back to comparisons only after presenting the four illustrative cases. In the concluding discussion I address what we can learn from this exploratory approach, outlining potential explanatory factors. In so doing, I delineate an agenda for future studies of MRD and regime change.

Multilevel Decoupling: Global Trends from the 1990s Onward

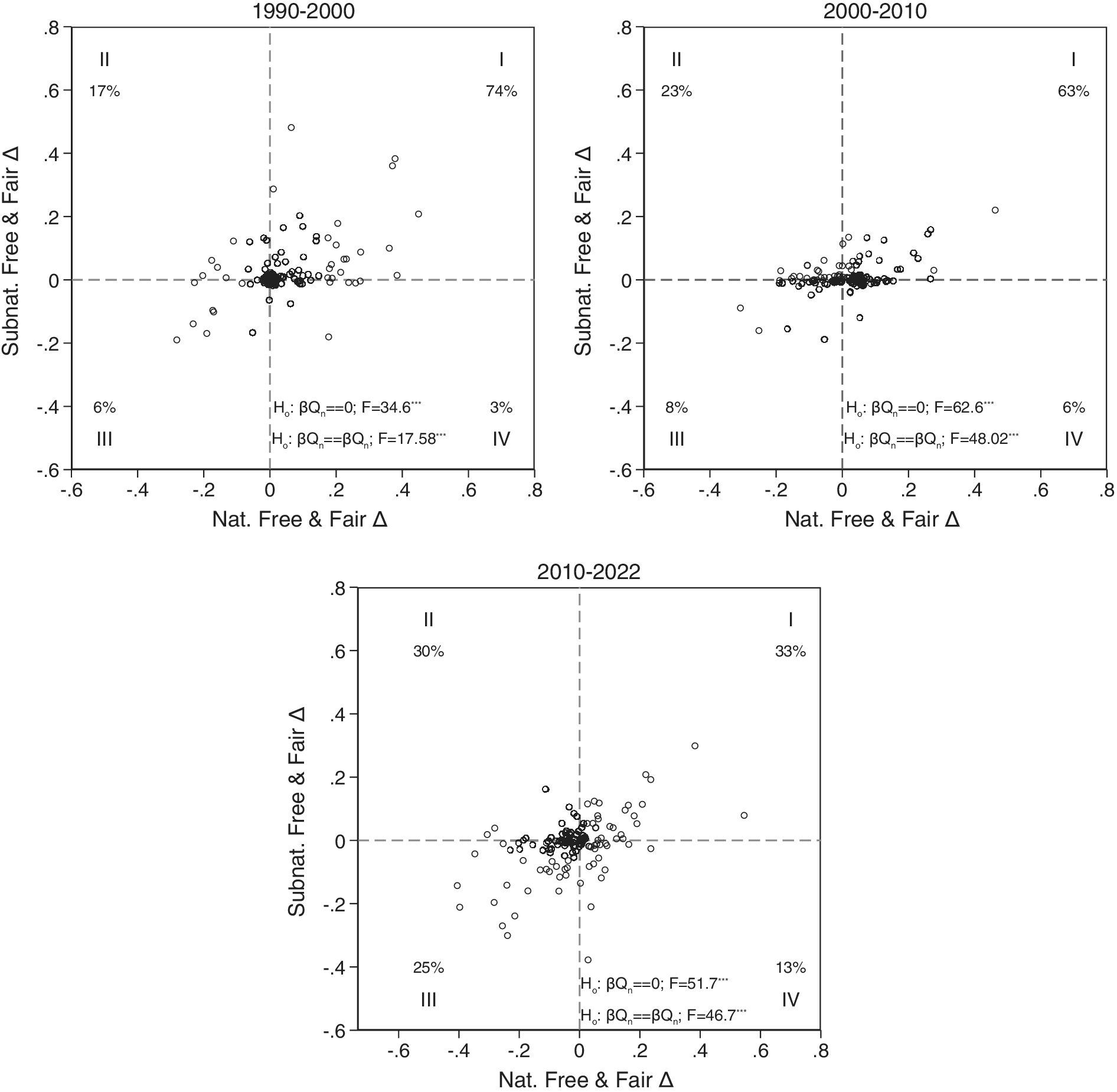

Using V-Dem data (v13), in this section I present global patterns of multilevel decoupling. The graphs on figure 3 track, from left to right, the last three decades of change in electoral democracy across territorial arenas.Footnote 10 In line with the conventional wisdom (Boese, Lindberg, and Lührmann Reference Boese, Lindberg and Lührmann2021; Ding and Slater Reference Ding and Slater2021; Huntington Reference Huntington1991), the 1990s were a decade of democratization, which for the most part (74% of observations) consisted of coupled democratic gains across territorial levels. During this period, only 6% of the world sample experienced movements away from free and fair elections at both territorial scales (QIII). Interestingly, in the 1990s, 20% of the sample underwent decoupled change, with “national erosion and subnational gains” (QII), being the most common type of MRD change with 17% of the cases.

Figure 3 Multilevel regime decoupling 1990–2022

Notes: Built by the author using V-Dem data (v13). Items and transformations are described in the text.

The middle graph plots changes for the first decade of the twenty-first century. Three things stand out: First, there is a clear contraction in the magnitude of change, marked by the clustering of cases around zero. Second, as in the previous decade, a sizeable proportion of cases (71%) still falls under the quadrants corresponding to territorially coupled regime change (QI and QIII). Third, the share of cases of multilevel decoupling increased to 29%. Unpacking the regional distribution of instances of decoupling during this period reveals these are for the most part cases in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and Central AsiaFootnote 11.

The last graph of figure 3 plots multilevel change from 2010 to 2022. This is the most relevant plot for discussing autocratization and contemporary regime change, as it shows some interesting patterns. First, the share of cases of territorially coupled regime change drops to 58%, the lowest over the three decades under observation. Second, since 2010, only 33% of cases can be considered instances of coupled democratization, which is less than half of the number identified in the 1990s. In line with our understanding of autocratization, a surprising 25% are coupled movements away from democracy, roughly three times more than the share observed in either of the previous two decades. Critically, this means that a surprising 43% of countries experienced multilevel decoupling (QII and QIV), more than double the number of cases recorded in the 1990s.

Third, when looking only at the national level, we can see that 55% (QII+QIII) of cases have indeed experience democratic erosion. However, only 25%—less than half—have been instances of coupled autocratization. Rather, a considerable proportion (30%) of cases of national democratic erosion have been accompanied by subnational democratic gains, at least in terms of free and fair elections. Similarly, in line with the data displayed in the introduction, the bottom of figure 3 shows that 13% of the cases which have experienced national democratic gains have also experienced an erosion of electoral democracy at the subnational level (QIV).

In sum, while the shifts observed in quadrants I and III are patterns conforming to previous findings in the literature, changes in quadrants II and IV shed light on multilevel decoupling, the territorial dimension of autocratization and contemporary regime change. Quadrants II and IV have therefore been overlooked in our extant assessments of how polities move away from democracy. Taken together, the plots in figure 3 suggest that multilevel regime decoupling has become an increasingly common phenomenon, and that, were this trend to continue in the coming decade, it will become the modal type of regime change around the globe. Indeed, exploring only the subset of democratic countries (Polity>5, shown in the online appendix), suggests that it already is.Footnote 12

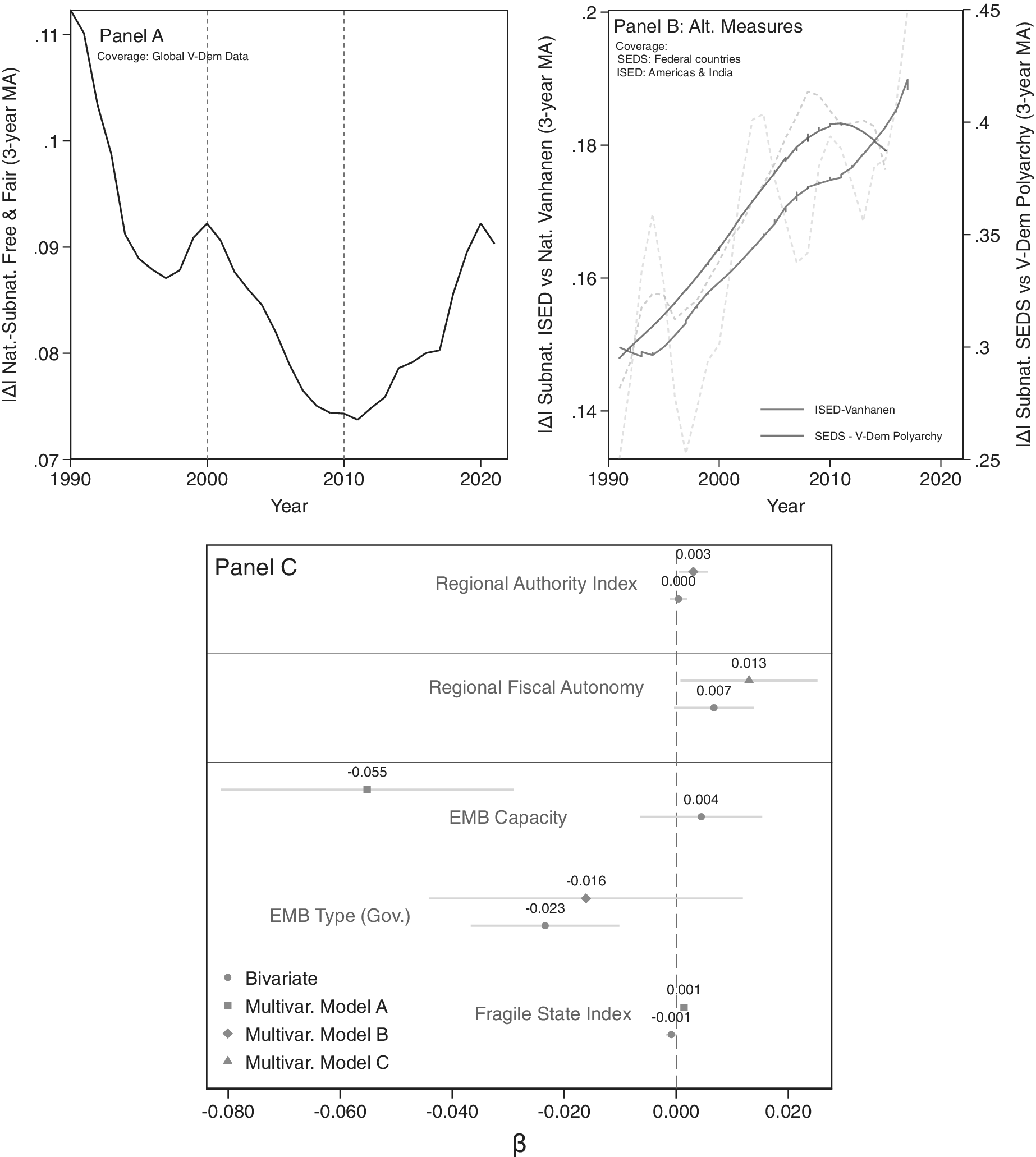

As indicated by the F-scores accompanying the plots in figure 3, the average difference across each quadrant is significantly distinct from zero, and the substantive results are robust to the exclusion of outliers and cases with values too close to zero.Footnote 13 Nonetheless, to further illustrate the salience of multilevel decoupling, Panel A of figure 4 plots the global average of the absolute value obtained by subtracting V-Dem’s subnational democracy proxy from the national one. As such, the emphasis here is not on identifying the share of country cases experiencing (de)coupled change but rather on capturing the “size of the gap” between national and subnational regimes through time. Following the same rationale, in Panel B of figure 4 I present the resulting trend lines from performing the same analysis using Fidalgo’s (Reference Fidalgo2021) SEDS and Sandoval’s (Reference Sandoval2023) ISED.

Figure 4 Further quantitative assessments of multilevel regime decoupling

Notes: In Panel C the dependent variable is the absolute value of the country-year difference obtained from subtracting V-Dem’s subnational democracy proxy from the national one. I report coefficients of factors that reach conventional levels of significance in either the bivariate or the fully saturated models. None of the factors explored meet these two conditions jointly.

Three things are worth noting: First, the global trendline based on V-Dem data declines until the early 2010s, indicating that between the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century regime differences across territorial levels were in fact declining. Second, the trends identified in Panel B, however, point in a separate direction: they suggest that the regime gap between the national and the subnational arenas has been rising since at least the 1990s. The discrepancy observed for the pre-2010s period could be due to either: a) the limitations of the V-Dem proxies discussed earlier, b) the increased granularity in capturing subnational democracy of both the SEDS and the ISED, or c) to the potential mismatch between these latter scores and the national proxies with which they were contrasted (V-Dem’s polyarchy and Vanhanen’s index respectively).

More research and better data are certainly needed to unpack the pre-2010 measurement discrepancy, since it indicates disagreement—not on whether MRD is occurring—but rather on when it started and on whether the rate at which MRD occurs has changed. Here I adopt a conservative approach by emphasising the third and most important fact for the argument defended in this paper, which is that whether one uses solely V-Dem data, or the more specialized proxies from the subnational literature, for the post-2010 period, all three trend lines send the same clear message: over the last decade, the gap between national and subnational regimes—that is, multilevel regime decoupling—has been on the rise.

Finally, drawing theoretically relevant factors from the extant literature,Footnote 14 and using the country-year values of the absolute difference (obtained by subtracting V-Dem’s subnational democracy proxy from the national one) as a dependent variable, in Panel C I summarily present the results from several probatory regression analyses. Here I only report the five variables whose coefficients reach conventional levels of significance in either bivariate or multivariate models. Thus, the first important thing to note is that none of the factors explored meet these two conditions jointly. In line with the conventional wisdom, regional autonomy and regional fiscal autonomy appear to positively influence decoupling. In addition, having a capable electoral management body, or one that is managed or controlled by government (as opposed to an independent EMB) seems to minimize the extent of decoupling. For its part, state capacity has an unexpectedly small, positive, and significant coefficient. Factors such as economic development, terrain ruggedness, ethnic fractionalization, and executive format were found not to significantly influence decoupling. Surprisingly, the coefficients of binary indicators of a country’s electoral system and of their federal (versus unitary) territorial arrangements were equally indistinguishable from zero. As such, to better elucidate decoupling and mindful of these quantitative findings, in the next section I explore four short descriptive case studies.

Four Descriptive Cases of (De)Coupled Change

Even when (electoral) democracy might advance in one territorial level, it might still erode in another one. In the previous section I provided quantitative evidence identifying (de)coupled change globally. To further elucidate this phenomenon, following the analytical strategy outlined in the Data and Empirical Approach section, here I draw on Italy and India as cases of coupled change, and South Africa and the United States as instances of decoupled movement. Although the analysis is necessarily non-exhaustive, I proceed following a descriptive “within case” logic and iterate back to theoretically relevant comparisons only in the concluding discussion.

Italy (Coupled Electoral Democratization)

At first glance, Italy seems like a counterintuitive example of coupled electoral democratization. Classic work, for example, has suggested that democracy works differently across Italian regions (Putnam, Leonardi, and Nanetti Reference Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti1993), and that historically weak subnational institutions doomed federalism in the country (Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2006). For their part, recent discussions on the politics of the peninsula reveal that Italy is in the midst of a right-wing, populist, illiberal hurricane (Donà Reference Donà2022). A pattern that started under Berlusconi’s rise to power in 1994 and endures with Giorgia Meloni’s victory in the snap election of September 2022 (Castaldo and Verzichelli Reference Castaldo and Verzichelli2020).

This illiberal backlash contrasts with the final report by the “Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights” (ODIHR) on that same September 2022 election, which concluded that the contest was competitive, that it offered voters a wide array of political alternatives, and that the political freedoms of individuals were respected during, before, and after the process (ODIHR 2023). Indeed, the Electoral Integrity Project gave the 2022 process a higher score than those assigned to the 2013 and 2018 elections (Garnett et al. Reference Garnett, James, MacGregor and Caal-Lam2023). Concomitantly, over the last decade, subnational elections across the twenty regions that configure the Italian territory have become increasingly contested, with a recent paper suggesting that in Italy “regional elections now clearly follow a logic of their own, [and are] dominated more by local leaders than [by] national parties” (Vampa Reference Vampa2021, 167).

The extensive scholarship on Italian electoral (Chiaramonte Reference Chiaramonte2015; Donovan Reference Donovan1995) and decentralization reforms (Giovannini and Vampa Reference Giovannini and Vampa2019; Leonardi Reference Leonardi1992; Leonardi, Nanetti, and Putnam Reference Leonardi, Nanetti and Putnam1981) suggests that the strength of the electoral dimension of democracy across Italy’s multilevel territorial structure was configured by a process of institutional layering (Baldini and Baldi Reference Baldini and Baldi2014; Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010). First, the volume of electoral rules is expansive. There are over 60 different laws and regulations shaping the distinct aspects of elections in Italy (ODIHR 2023). The frequency with which they are modified set Italy apart from the conventional European experience, with scholars identifying a cyclical relation between electoral reform and changes in the party system (Baldini Reference Baldini2011). Second, these modifications have overlapped with an equally considerable number of attempts to (re)define the role of regional and local governments in the peninsula (Baldini and Baldi Reference Baldini and Baldi2014).

On one hand, this regulatory proliferation is indeed a source of fragmentation, which opens the space for opacity, mismanagement, and the potential for uneven electoral practices. Indeed, already at the turn of the twenty-first century Italy was undergoing a growing territorial divide over preferences for territorial institutional design (Baldini and Vasallo Reference Baldini and Vasallo2001)—a dynamic reflective of Italy’s strong political and regional autonomy (Ladner and Baldersheim Reference Ladner and Baldersheim2016). On the other hand, this layered regulatory matrix provides enough flexibility to respond to domestic pressures, to incorporate international recommendations, and to respond to local pressures (ODIHR 2023). At the national level, among other things, legislation in 2017 introduced a parallel voting system, changing Italy from a proportional to a mixed electoral system. A reform in 2019 then improved the transparency of donations in campaign financing, and in 2020 the voting age for the Upper House changed from 25 to 18.

At the subnational level, a reform in 1999 introduced the direct election of regional presidents, and a second wave of modifications at the turn of the twenty-first century allowed regions to increasingly delineate their own voting systems (Floridia Reference Floridia2014). The former has allowed regional leaders to be more responsive to their local constituents, thus pushing towards the “de-nationalization” of party-politics (Vampa Reference Vampa2021; Wilson Reference Wilson2015). This latter phenomenon has pushed in a similar direction by increasing the salience of local or personal candidate lists at the cost of party labels.

Moreover, in Italy, elections have been traditionally under governmental purview, with the Central Directorate for Electoral Services, the Ministry of the Interior, and the Municipal Electoral Offices configuring a capable electoral management body (EMB) (Garnett Reference Garnett2019). For its part, the Italian Parliament, under Article 66 of the Constitution, has customarily held the authority to address any potential disputes related to electoral outcomes. In 2009, however, a group of citizens argued that the allocation of a majority premium to the largest list coalition transgressed their voting rights, as it prevented them from selecting their preferred candidate. The case reached the Italian Constitutional Court, and in 2014, the Court “abruptly abandoned its [past] reluctance to get involved in matters of electoral legislation” (Faraguna Reference Faraguna2017, 782). In the aftermath of the 2014 ruling, the Court has been an active player in shaping the electoral arena—across multiple territorial levels—with some scholars suggesting that increasingly Italian elections are “disciplined” by the judiciary (Musella and Rullo Reference Musella and Rullo2020).

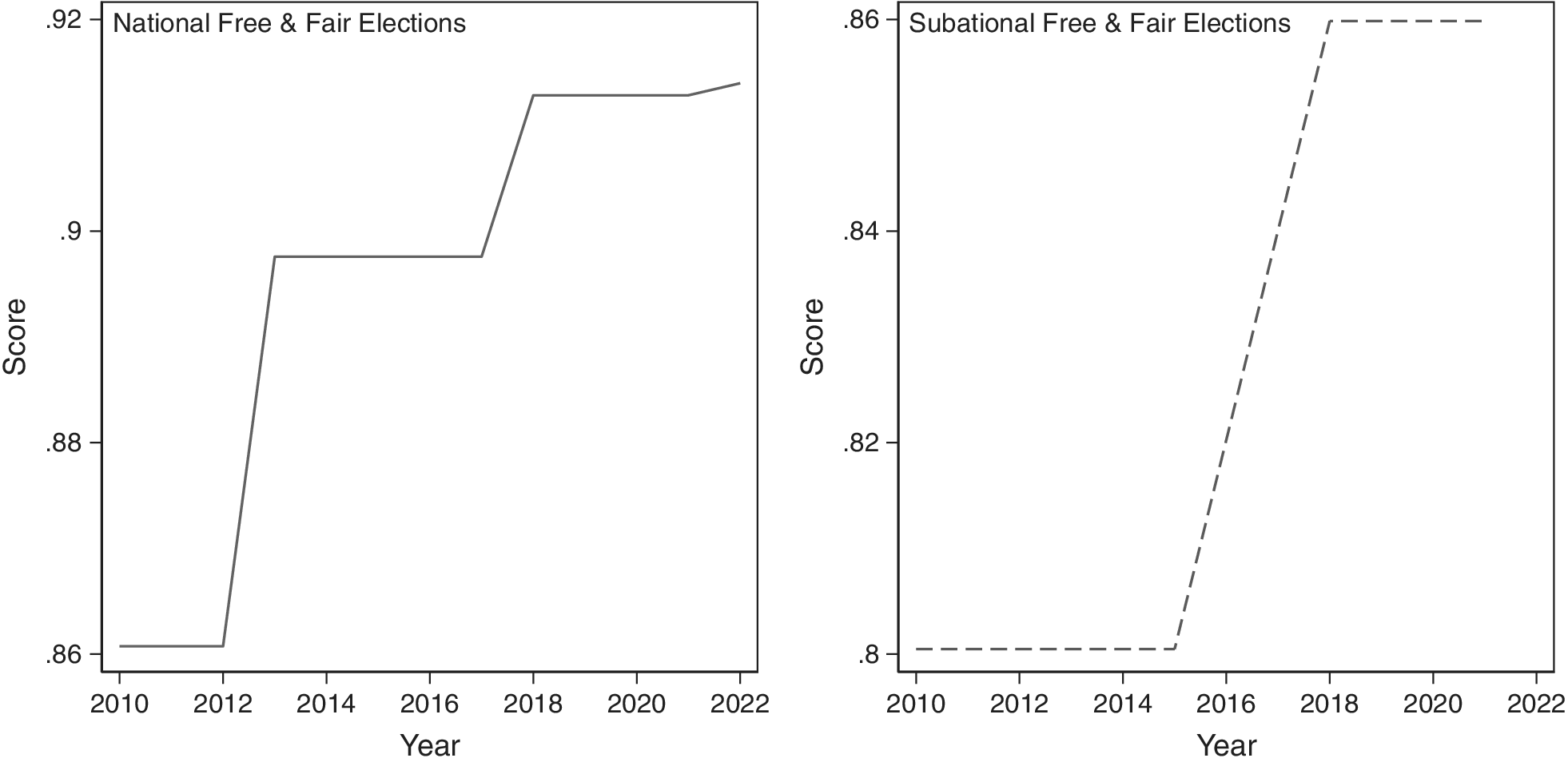

Figure 5 shows the 2010–2022 trends in the V-Dem items capturing free and fair elections at the national and the subnational level in Italy. This brief case exploration colours those trends, showing that a complex and fragmented matrix of electoral regimes—which continues to operate under a capable governmental EMB—has been increasingly disciplined by the Courts.

Figure 5 Italy 2010–2022: Coupled electoral democratization

Institutional change has been an almost permanent feature of Italian politics and scholarship (see, for example, Fabbrini (Reference Fabbrini2005, Reference Fabbrini2009) and Pasquino (Reference Pasquino2019) for a discussion on the Italian transitions between different models of democracy). Despite, or perhaps because of, this constant search for improved institutional arrangements, electoral democracy across the Italian peninsula has been safeguarded and has even moderately improved across territorial scales.

India (Coupled Electoral Autocratization)

Until recently, India was famously the world’s largest democracy. In the aftermath of independence, the Constitution of 1950 set up a parliamentary, federal, multi-party democracy that has puzzled political scientists for decades. Indeed, democratic governance in the sub-continent was considered a “contemporary exception” (Dahl Reference Dahl1989), as its complex social structure and level of development stacked the odds against democracy (Przeworski et al. Reference Przeworski, Álvarez, Cheibub and Limongi2000). Nonetheless, barring the 1975–1977 rupture,Footnote 15 since 1947 the country has held 17 national and 389 state elections, with alternations both at the national and the subnational level. In the early 1990s, the country extended democracy to Panchayats (the third governmental tier), opening the door for millions of local offices to be elected every five years (Varshney Reference Varshney, Mainwaring and Masoud2022b). As such, while the liberal dimension of democracy usually lagged behind the electoral one (Varshney Reference Varshney2022a), India was a clear example that multilevel democracy can indeed emerge in “hard places” (Mainwaring and Masoud Reference Mainwaring and Masoud2022).

The narrative, and the real-world dynamics of India changed first in Guyarat, where then Chief Minister Narendra Modi (2001–2014) tested a regime model (which has been labelled authoritarian (Sud Reference Sud2022)), that he has since tried to implement across the country after becoming India’s Prime Minister under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 2014. At the national level, in 2019 Modi managed to renew and expand his mandate, securing the first consecutive majority since 1971. In 2019 Modi also introduced the Citizen Amendment Act which effectively created a religious and ethnic filter to Indian citizenship (Ganguly Reference Ganguly2020). Without citizenship, Muslims, jews, and atheists risk not only being “manufactured foreigners” (Deb Reference Deb2021), but critically, they risk electoral disenfranchisement. This comes atop the 2017–2018 election finance reforms, which introduced “electoral bonds” as a new mechanism for individuals and corporations to donate money to political parties which, by accounts of international observers, made campaign financing more prone to corruption (Kronstadt Reference Kronstadt2019). Rather than being punished at the poll for his Hindu-nationalist populism, Modi and his BJP party have been rewarded for it.

Historically, India’s electoral scaffolding has been independent and robust (Ganguly Reference Ganguly, Ganguly and Plattner2007). However, oversight by the Election Commission of India (ECI) has come under closer scrutiny. For example, the ECI’s tardiness in restricting pro-Modi and pro-BJP content by the NaMo TV channel during the 2019 elections, which opposition parties claimed violated the ECI’s own Model Code of Conduct, have raised concerns about an institutional, electoral bias in favour of the BJP. At the time, Rahul Gandhi—head of the Congress party, and Modi’s main opponent—accused the ECI of “capitulating before Modi” (Indian Express 2019). Scholars of India have echoed these concerns, underscoring that the “ECI now stands compromised in the eyes of voters” (Ganguly Reference Ganguly2020, 197). It should come as no surprise then, that India’s “credible elections” score reported by IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Initiative (GSoD) (Global State of Democracy Initiative 2023) has dropped consistently since 2010. Indeed, the V-Dem Institute concluded that already by 2020, India had turned into an “electoral autocracy” (Alizada et al. Reference Alizada, Cole, Gastaldi, Grahn, Hellmeier and Kolvani2021).

At a lower territorial scale, despite shrinking fiscal autonomy at the state level (Mahamallik and Sahu Reference Mahamallik and Sahu2023), the 1990s and the early 2000s were decades in which subnational democratization entailed the break-up of the dominant Congress Party (Tudor and Ziegfeld Reference Tudor, Ziegfeld, Behrend and Whitehead2016). Harbers, Bartman, and van Wingerden (Reference Harbers, Bartman and van Wingerden2019) provide a clear framework to understand threats to subnational democracy in India. From a “horizontal” viewpoint, they underscore the salience of state and non-state armed groups, which often call for boycotting elections, and which “have at times succeeded in disrupting the electoral process systematically and violently” (Harbers, Bartman, and van Wingerden Reference Harbers, Bartman and van Wingerden2019, 1155). From a “vertical” perspective, although they pay special attention to the misuse of President’s Rule, their vertical rationale can be extended to the broader set of intergovernmental relations, including Court rulings and the strategic decisions made by state governments vis-à-vis local ones (Harbers, Bartman, and van Wingerden Reference Harbers, Bartman and van Wingerden2019).

Regarding President’s Rule, article 356 of the Constitution of India allows the centre to suspend popularly elected state-level governments. As such, President’s Rule disrupts subnational democracy. Between 2010 and 2022, this instrument has been used 14 times, 10 of which have been under Modi’s tenure.Footnote 16 While this formal mechanism has been used strategically in the past, beyond formal instruments, journalistic accounts suggest Modi has politically weaponised law enforcement, using it to discredit, harass, and intimidate subnational officials who refuse toe the BJP’s line (Saaliq Reference Saaliq2020; Sharma and Saikia Reference Sharma and Saikia2022).

Moreover, while the ECI oversees national and state level elections, electoral processes for third-tier Panchayats fall under the purview of the states. As such, state governments across the political spectrum have routinely engaged in “tactical delays,” postponing local elections to maximize(minimize) vote gains(losses). In addition, state governments have taken steps to regulate the tenure and conditions of service of State Election Commission (SEC) officers. These tactical delays and regulatory incursions from second- to third-tier governments have been resisted by opposing parties within Indian states, and several cases have reached the Supreme Court. For the most part, the judiciary has asserted the prerogative of state governments over Panchayats and municipalities (Raza, Gupta, and Shukla Reference Raza, Gupta and Shukla2020).

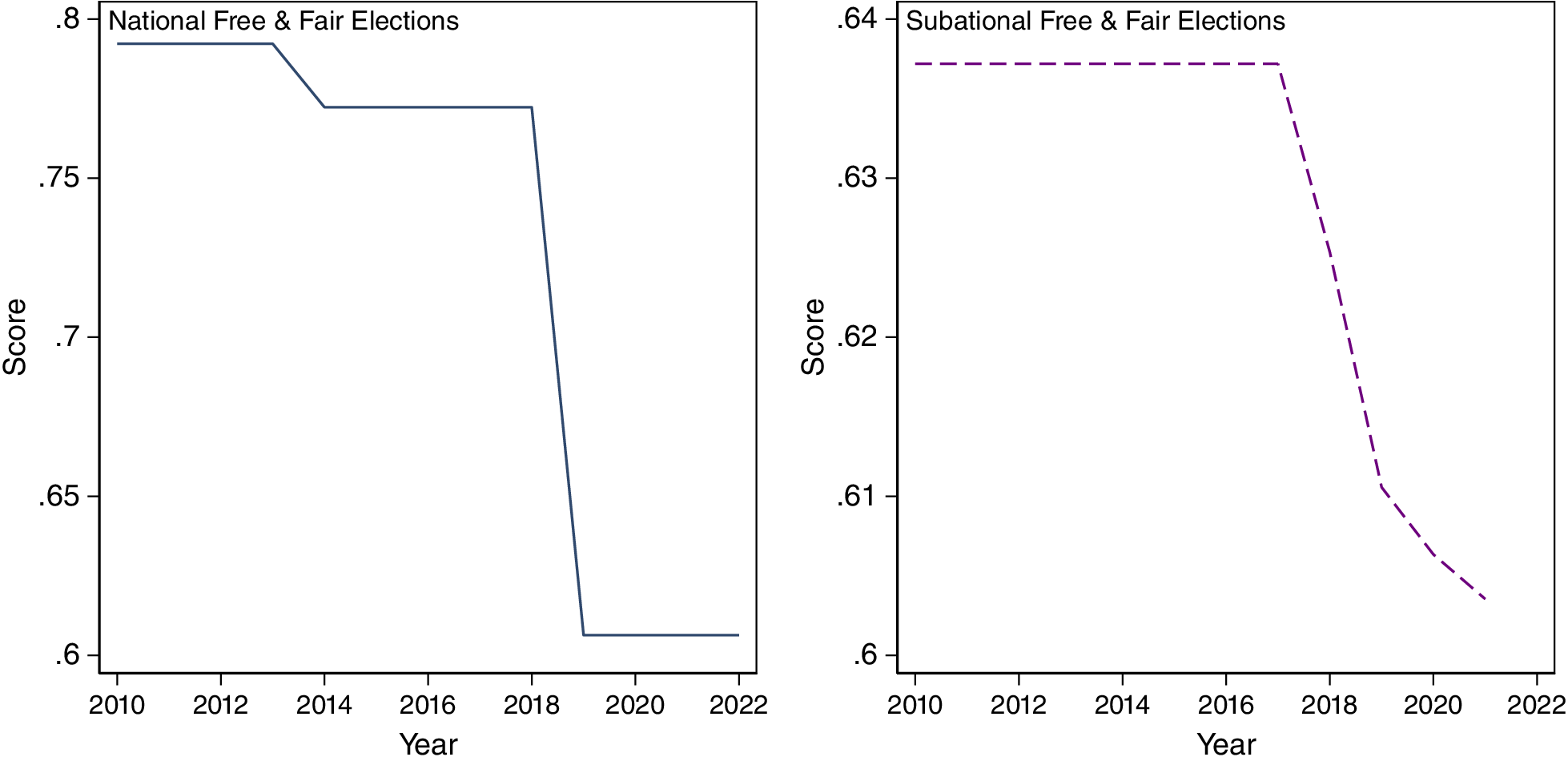

Almost a decade ago, observers of India discussed how the country’s extensive quota system (known as “reservations”) strengthened national electoral democracy by fostering inclusion and mobilization (Jensenius Reference Jensenius2017). Back then, at the local level, the discussion was centred on how subnational democracy was bolstered to increase internal party cohesion by outsourcing to voters the costs of monitoring and disciplining local candidates (Bohlken Reference Bohlken2016). Today, however, this exploratory analysis has shown that the centre has weakened a hitherto robust EMB, and it continues to strategically intervene Indian states. Moreover, politicians in the latter subnational level also “adopt tactics to delay Panchayat and Municipal elections according to their whims and fancies” (Raza, Gupta, and Shukla Reference Raza, Gupta and Shukla2020, 60). With courts asserting state-level electoral jurisdiction, reports of electoral rigging and intimidation are becoming widespread at the local level (Martin and Picherit Reference Martin and Picherit2020). Figure 6 and the dynamics just described illustrate that in India, autocratization has been territorially coupled, with democracy eroding at the national and the subnational level.

Figure 6 India 2010–2022: Coupled electoral autocratization

South Africa (Decoupled Change: National Erosion, Subnational Gains)

The African National Congress (ANC)—a liberation movement turned political party—has dominated politics in post-apartheid South Africa. In the 1990s, the set of reforms that accompanied the interim constitution of 1993, and that culminated in the adoption of the current magna carta in 1996, shaped a unitary and proportional parliamentary democracy that is heavily decentralized (Koelble and Siddle Reference Koelble, Siddle and Erk2018; Reddy and Maharaj Reference Reddy, Maharaj and Saito2008) and has a powerful national executive (Cranenburgh Reference Cranenburgh2009). Indeed, the multiple and tumultuous efforts to dismantle racial and ethnic-based apartheid politics shaped the institutional design of South Africa. In an effort to cease civil strife and avoid secession, this process entailed the establishment of provinces and local governments, along with an increasing recognition of their administrative and political autonomy (Dickovick Reference Dickovick2014).

After Mandela, Thabo Mbeki (1999–2008) oversaw the implementation of a liberalizing economic agenda, of which the “Growth, Employment, and Redistribution” (GEAR) plan and the “Black Economic Empowerment” (BEE) policy are perhaps the best-known examples (Makgoba Reference Makgoba2022). Economic change heightened the cross-cutting salience of race and class (Nattrass and Seekings Reference Nattrass and Seekings2001) and were accompanied by increased corruption, cronyism, and “neopatrimonialism.”Footnote 17 Economic reforms also weakened the fiscal autonomy of South African provinces as they became more dependent on intergovernmental transfers from the centre (Dickovick Reference Dickovick2005). The adoption of a (neo)liberal economic agenda also had political costs. Mbeki clashed with the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and with the South African Communist Party: the two left-wing partners of ANC’s governing “Tripartite Alliance” (Sutnner Reference Sutnner2002). Mbeki’s persona, his attitude towards media, and his opposition to the HIV/AIDS Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) signalled a turn in ANC’s commitment to democratic norms and procedures that would only intensify under his successor Jacob Zuma (Msimang Reference Msimang and Magaziner2020).

Supported by anti-Mbeki sentiment, Zuma gained national traction by capitalizing ethnic and nationalist tropes in the midst of a rape trial in which he was the accused. Zuma’s populist illiberalism (Vincent Reference Vincent2011) was accompanied by a programme of “Radical Economic Transformation” which aimed to counter his predecessor’s market-oriented reforms and re-assert the economic role of the state (Desai Reference Desai2018). This initiative, however, catalysed State capture, deepening corruption and the embezzlement of public funds (Bracking Reference Bracking2018), symptoms that were crystalized by the Nkandla scandal, which shed light on Zuma’s use of public funds to improve his private residence, and that ultimately forced him out of power in 2018.

Against this background, albeit still considered an “electoral democracy” by the V-Dem Institute (Papada et al. Reference Papada, Altman, Angiolillo, Gastaldi, Köhler, Lundstedt and Natsika2023), the increased tensions between the executive and the media, the heightened neopatrimonial features of the governmental apparatus, in conjunction with the continued dominance of the ANC have, to some extent, eroded the credibility of elections in South Africa. In 2014, for example, the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC)—a state-owned radio and TV broadcast station—censored campaign spots from “Democratic Alliance” (the ANC’s main opposition party). Reflecting on the 2014 process, Martin Plaut later concluded that “[t]here is no doubt that the ANC would have won … even if there had been an entirely clean election, but the election was flawed and [it] should be recognised as such” (Plaut Reference Plaut2014, 642).

Indeed, public trust in South Africa’s constitutionally independent Electoral Commission (IEC) hit a record low in 2021, with 57% of Afrobarometer respondents stating they had little to no trust in the IEC (Moosa and Hofmeyr Reference Moosa and Hofmeyr2021). Moreover, as reported by international observers, there has been an increasing number of electoral objections, which jumped from 8 in 2004, to 56 in 2019 (Independent Electoral Commission 2019). Understandably, IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) “credible elections” score for South Africa has dropped consistently in the 2010–2022 period.

The picture that emerges from looking at South Africa’s subnational arena is slightly different. On one hand, while the ANC has not lost any national election, the opposition has been moderately more successful in securing provincial and municipal seats (Rulea Reference Rulea2018). Historically, Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal have been the provinces in which the opposition has remained competitive. Recently, granular analysis of wards, the lowest electoral unit in South Africa, has shown that good government performance by the ANC-opposing “Democratic Alliance,” improves their electoral support in those wards and in neighbouring ones (Farole Reference Farole2021). In addition, ANC’s factionalism and in-fighting usually involves subnational splits, which benefits the electoral chances of the opposition at the local level (Mukwedeya Reference Mukwedeya2015).

The judiciary has played an interesting role in South Africa, in that at worse it has been ambivalent towards subnational units, and at best it has been “favourable to local [third tier] governments but not to the provinces” (Steytler Reference Steytler, Aroney and Kincaid2017, 335) (emphasis added). For example, in 2013 the Electoral Court ruled to postpone a by-election after the local electoral office failed to register a group of independent candidates on the basis of a “clerical error” (Johnson and Others v. Electoral Commission and Others 2013). More recently, in 2022, the court ordered a re-enactment of a local by-election after determining that the original procedure, in which an ANC candidate had emerged victorious, had been marred by irregularities (Kortman and Another v. Electoral Commission of South Africa and Others 2022). Reviewing these and a sample of other similar court rulings from the last decade shows that the court has been inclined to enforce electoral acts and regulations over state and local actors.

Already by 2015, scholars examining a battery of subnational electoral indicators including the regularity of elections, the legal framework, the extent of suffrage restrictions, the composition of local assemblies, whether the opposition boycotted elections, and whether the ANC accepted defeat, concluded that South Africa has all these attributes “at sufficiently high levels” (Muriaas Reference Muriaas, Spanakos and Panizza2016, 84). When looking at international indicators, for example, in 2022 IDEA’s GSoD local democracy indicator gave South Africa the highest score in the African continent. Based on this metric, by 2022 the South African subnational arena was comparable to that of Chile, Colombia, or the United Kingdom. In sum, figure 7 and this brief incursion into South African contemporary politics illustrate that in the “Rainbow Nation,” democracy has recently decoupled across territorial levels. It has eroded in the national arena and improved in the subnational one.

Figure 7 South Africa 2010–2022: Decoupled change (national erosion, with subnational gains)

United States of America (Decoupled Change: National Recovery, Subnational Erosion)

Recent discussions on the erosion of democracy in the United States have punctured the myth of American exceptionalism. At the national level, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2023) have underscored that in the United States, backsliding (and even the threat of democratic breakdown) is real and increasingly palpable. At the subnational level, the myth of American exceptionalism was also deflated first by Mickey’s exploration of “southern authoritarian enclaves” (Mickey Reference Mickey2015), and then by Grumbach (Reference Grumbach2022) and others (Rogers Reference Rogers2023) who have shown how states subvert local democracy. At the core of this debate lie four of the pillars of American political development: federalism, party politics, race, and suffrage politics.

From inception, the U.S. Constitution gave states ample prerogatives, giving rise to a regulatory “patchwork” (Mettler Reference Mettler1998), and to a cycle in which national and subnational actors vie to define the scope and the territorial boundaries of conflict (Gibson Reference Gibson2012; Schattschnieder Reference Schattschnieder1960). Indeed, the historic “Solid South” rested on a variety of local electoral regulations such as reading qualifications or tax paying requirements. Bottom-up pressures from a strong civil rights movement, marked by protest and extensive civil litigation, gradually built up pressure, and culminated with the introduction of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in 1964 and 1965 respectively (Holt Reference Holt2023). Reacting to court rulings that diminished the act’s impact on equal political rights—by favouring states over national legislation—the VRA has been amended five times since its introduction (1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, 2006). In other words, the amendments have aimed to ensure minimal voting rights standards across American states. As such, in the Unites States “suffrage … has been contested … its expansion has been anything but linear, and retraction and expansions have been contingent throughout [history]” (Mickey Reference Mickey2015, 352).

Recently, economic inequality (Hoffmann, Lee, and Lemieux Reference Hoffmann, Lee and Lemieux2020), immigration, and social heterogeneity (Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2019) have fuelled the so-called “culture wars” (Jacoby Reference Jacoby2014). In the political arena, growing partisan polarization (Hare and Poole Reference Hare and Poole2014) has extended conflict into different policy domains, such as security and education. Polarization has increased the internal national cohesiveness of parties at the costs of local interests (Grumbach Reference Grumbach2022; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2018), and it has also increasingly politicized the judiciary (Hasen Reference Hasen2019). In this context, the Trump presidency—enabled only by a counter-majoritarian Electoral College—can be seen as “the product of the intersection of an institutional crisis, fundamental disputes over identity, and the breakdown of fundamental [democratic] norms” (Bernhard and O’Neill Reference Bernhard and O’Neill2019, 322).

Against this backdrop, the subnational democratic arena has eroded considerably in America. On one hand, gerrymandering—the strategic outlining of district boundaries—continues to be a pervasive practice (Kang Reference Kang2020). On the other hand, recent decades have been characterised by “selective devolution” (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2023) in which a politicized court advances partisan goals by asserting the autonomy of states. Indeed, by striking down the coverage formula (Section 4b) of the VRA in 2013, the Supreme Court eliminated the requirement for jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to “clear” any change to voting procedures with the Department of Justice (DOJ). This ruling has led to cuts in early voting, stricter voter identification laws, purges of voter rolls, and a reduction of polling locations (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 2018; Feder and Miller Reference Feder and Miller2020) In 2021, by upholding Arizona’s “third-party ballot collection ban” and the state’s “out-of-precinct” policy, the Supreme Court again made the headlines by making future judicial challenges to discriminatory local voting laws harder (Morales-Doyle Reference Morales-Doyle2021).

In the national arena, the 2016 U.S. elections were indeed not only incredibly polarized, but polarizing, as allegations of foreign interference deepened partisan divides (Tomz and Weeks Reference Tomz and Weeks2020) and “decisions on technical aspects of the electoral process were often motivated by partisan interests, adding undue obstacles for voters” (ODIHR 2016). In fact, the Electoral Integrity Project concluded that both the 2016 and the 2020 U.S. presidential elections only “moderately” met international standards, ranking below the average for countries with comparable incomes. It is in this context that the Trump-fuelled allegations of fraud ultimately led to the assault of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.

If the subnational democratic arena has been eroded, and if in the U.S. elections are administered by state governments and local jurisdictions, how can we understand that America was classified as a case of decoupling with subnational losses, but national gains in the electoral dimension of democracy (Quadrant IV)? There are three factors that elucidate this issue. First, all electronic systems used for electoral purposes were designated as “critical infrastructure” in 2017. The cybersecurity of elections is now under the purview of the corresponding agency within the Department of Homeland Security (ODIHR 2022). Relatedly, in November 2020, a group of computer scientists publicly declared that no credible evidence of computer fraud had been found in 2020 (U.S. Expert Statement 2020). More broadly, rigorous research on the security and administrative anomalies of recent U.S. presidential elections has shown that “what is purported to be an anomalous fact about the election result is either not a fact or not anomalous” (Eggers, Garro, and Grimmer Reference Eggers, Garro and Grimmer2021, 6).

Second, when reviewing the electoral reports throughout the 2010–2022 period from either the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) or from the U.S. Federal Election Commission (FEC), international and domestic observers express and reiterate their confidence in the ability of officials and individuals involved in the administration of elections to do so professionally and impartially. Democratic norms may indeed have eroded, but electoral institutions seem to have survived Trump, and partially recovered strength in the aftermath of his presidency. However, this relative optimism is tempered by the recognition that in a polarized nation, politics gets “dirtier” (Foa and Mounk Reference Foa and Mounk2021), with actors from across the political spectrum being more willing to undermine the informal protocols of political competition, and less likely to agree on the fundamental rules of the democratic game.

Third and last, even when conceding that subnational biases should distort the national electoral process, an interesting and recent study found that the partisan bias introduced by local gerrymandering almost completely cancels out at the national level (Kenny et al. Reference Kenny, McCartan, Simko and Imai2023). That is, gerrymandering presents a particular threat for subnational democracy, but because both Democrats and Republicans engage in strategic redistricting, its adverse effects are minimized at the national scale.

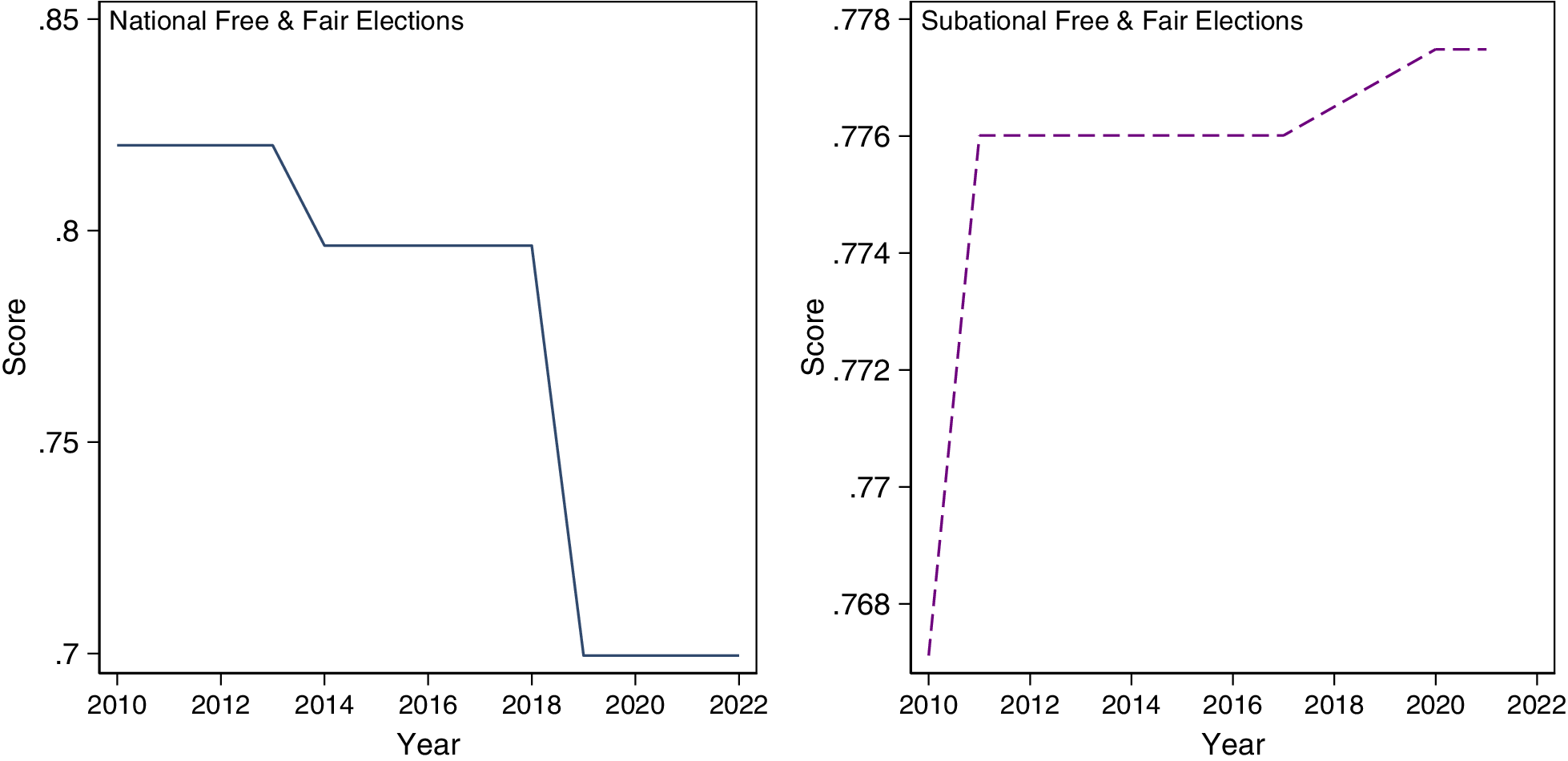

So, the analysis suggests, and figure 8 shows, that we need to qualify that more than gains, the U.S. national electoral arena recovered after 2016, while the subnational one has continued to erode since. America’s “marbled federalism” (Weissert Reference Weissert2011) is one in which multiple “suffrage regimes” (Valelly Reference Valelly, Valelly, Mettler and Lieberman2014) coexist, and while some are increasingly restrictive, when it comes to contemporary changes in electoral democracy, in the United States the whole has been more that its individual parts.

Figure 8 United States of America 2010–2022: Decoupled change (national recovery, with subnational erosion)

Conclusion: Elucidating Multilevel Regime Decoupling

In the fifteen years since the first warnings of “democratic recession” (Diamond Reference Diamond2008), scholars have conceptualised democratic retrenchment under the paradigm of autocratization. Bridging what we know about recent episodes of national regime change with insights provided by the scholarship on subnational regime heterogeneity, I have explored the territorial dimension of contemporary regime change. I show that worldwide, regimes across territorial levels are increasingly moving in separate directions. If this trend continues, multilevel decoupling can become the modal type of regime change globally in the next decade. A territorial approach then sheds lights on not only the direction of democratic shifts but also on the spatial locus of those changes, underscoring the growing gaps emerging between the national and the subnational level.

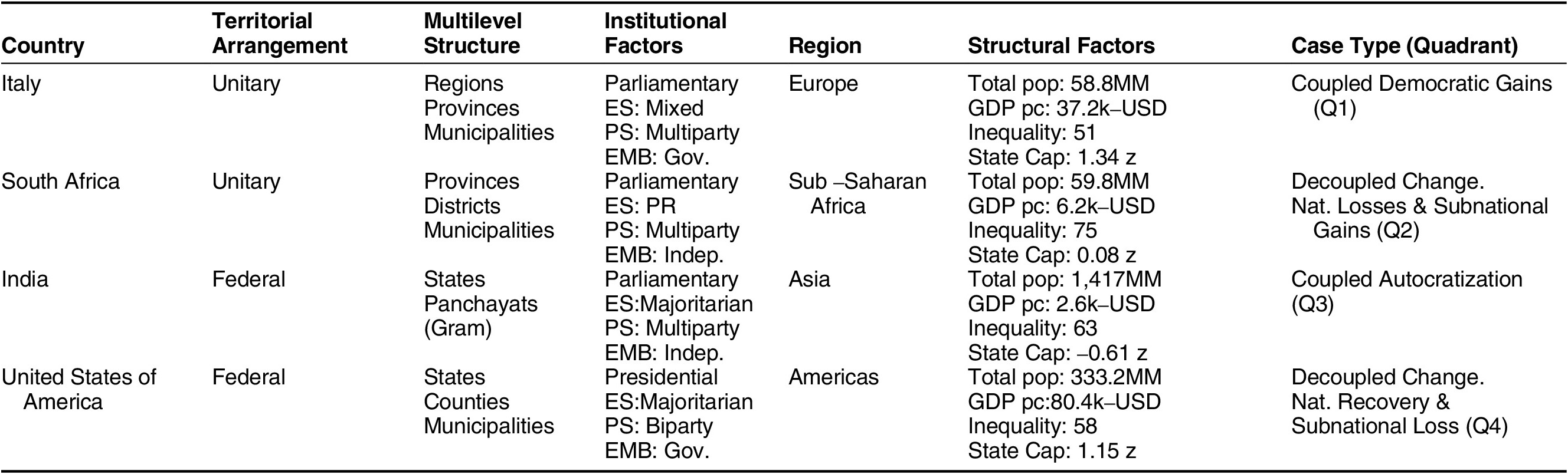

The key lesson is that autocratization, and regime change more broadly, are not simply a story of territorially homogenous change. It is also about the inherent tensions between national and subnational regimes inside countries. To delineate an agenda for future research, I conclude by reflecting on the following questions: What can we learn about multilevel regime decoupling from the quantitative data and from the four cases explored? What clues do these pieces of evidence offer for future research? To ease this corollary discussion, table 2 provides information on relevant structural, institutional, and territorial variables for the examined cases.

Table 2 Summary of Cases

Sources: Compiled by the author using the latest available data from International IDEA, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the CIA World Fact Book, the World Inequality Database, the Center for Systemic Peace as well as official governmental sources.

Notes: ES=Electoral system, PS=Party system, EMB=electoral management body, MM=millions, k= thousand. GDP per capita expressed in current US Dollars. Inequality is measured as the market or pre-tax income Gini coefficient. State capacity is expressed as z-scores based on the global average of the State Fragility Index (positive scores indicate higher state capacity).

The South African and the American experiences illustrate that decoupling can occur in developed and developing countries, and in countries with different territorial arrangements, different executive formats, different electoral and party systems, as well as in countries with varying levels of state capacity. Based on the qualitative and quantitative assessment, we can also say that MRD is not circumscribed to a specific region. In addition, looking comparatively at our cases of multilevel decoupling and those of coupled democratic change, reveals that different degrees of political and administrative decentralization, and different types of patronage might be enabling factors, but they do not necessarily guarantee the occurrence of MRD. The same can be said about populist or illiberal executives.

If most of the institutional and socioeconomic “usual suspects” of comparative politics do not satisfactorily disentangle the puzzle of multilevel decoupling, where can we begin searching for explanatory clues? The cases suggest that courts, and more specifically court rulings on electoral issues, can be plausible, non-trivial (f)actors that trigger or enable sequences of multilevel (de)coupled change. For example, had the Supreme Court in the United States decided differently in 2013, it is unlikely that we would have observed restrictive local electoral laws mushroom in the way they did. Had the Court in Italy decided not to step into the electoral domain, it would have perhaps enabled politicians to encroach on the subnational arena just as they have in the United States. Similarly, if the judiciary in South Africa had ruled in favour of second tier and central political actors, like the Courts in India have done, it is likely that the subnational democratic arena in the Rainbow Nation would have eroded just as it has in the Asian subcontinent.

Examining the evidence comparatively also suggests that not all court rulings on electoral matters are likely to have the same weight. In this sense, as figure 9 hints, courts can play a pivotal role in determining whether the sequence through which democracies change will lead to or involve multilevel decoupling. Moreover, once the arena or the territorial locus is set, political parties also seem to be relevant to the unfolding of MRD. This consideration echoes classic and contemporary discussions around national and subnational parties and party systems, inviting us to reassess the extent to which they converge in terms of size, electoral support, and their ideological orientation (Gibson and Suarez-Cao Reference Gibson and Suarez-Cao2010; Jaramillo Reference Jaramillo2023; Jones and Mainwaring Reference Jones and Mainwaring2003; Thorlakson Reference Thorlakson2020).Footnote 18 Taken together, the preliminary quantitative and qualitative evidence suggests that MRD is likely an equifinal outcome (Mahoney, Goertz, and Ragin Reference Mahoney, Goertz, Ragin and Morgan2013) and that an actor-centred approach is potentially better suited to explain it.

Figure 9 Recent sequences of multilevel (de)coupled regime change in Italy, India, South Africa, and the USA

MRD is thus a fertile ground for future research. Does decoupling affect democratic resilience? If so, how? What are the institutional configurations most conducive to (de)coupled regime change? Do some sequences of (de)coupled democratic change lead to more(less) resilient forms of autocratization? Which strategic political alignments and interactions more frequently lead to (de)coupled change? These are questions and considerations that stem from non-exhaustive, minimal re-writes of history (Mahoney and Barrenechea Reference Mahoney and Barrenechea2017). In and of themselves, these reflections raise more questions than answers.