One of the most powerful stimulants of political behavior is a feeling of threat. Immigration can cause natives to feel threatened and adopt prejudicial attitudes toward minority groups (Quillian Reference Quillian1995), neighborhoods that become more homogenous can vitiate threat and lead individuals to politically disengage (Enos Reference Enos2016), and projected demographic changes can generate a conservative shift among members of a majority group who worry about their status (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014). Similarly, individuals join interest groups during threatening times, such as when women joined the League of Women Voters to lobby school boards in response to dwindling government support for education (Hansen Reference Hansen1985). Citizens also reprioritize their preferences when a given identity feels threatened—for instance, Democratic parents support relatively strict sentences for sex offenders, a position counter to one endorsed by many Democrats, when they perceive their parental identity to be under siege (Klar Reference Klar2013), and administrators display racial bias in decision making when they perceive racial minorities to have a political agenda (Druckman and Shafranek Reference Druckman and Shafranek2020).

The sources of threat come in many guises, but they are often akin to what Truman (Reference Truman1951) conceptualizes as “disturbances”—that is, system-disrupting developments that cause individuals to feel anxious, thereby prompting action. Here, we study a remarkable phenomenon set off by recent disturbances: a massive surge in gun purchases that began immediately following the outbreak of COVID-19 and continued through a summer of protests and a tumultuous election cycle. During 2020, a record-breaking total of approximately 22 million firearms were sold with (an also record-breaking) 17 million Americans making a purchase. These numbers amounted to an increase of approximately nine million and four million from the prior year, respectively. Notably, the spike first appeared in FBI background check data for April 2020, shortly after COVID-19 had established itself in all 50 states (Denham and Ba Tran Reference Denham and Tran2021; Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Berman, Spolar, Rozsa and Tran2021; Nass and Barton Reference Nass and Barton2020; Tavernise Reference Tavernise2021). This was the start of one of the largest-scale disturbances of the last century—the COVID-19 pandemic—which was quickly followed by historic protest events and political turmoil that together threatened the health of the country and its economic and social well-being. These disturbance-driven gun purchases raise numerous questions; our focus here is on their consequences for the future of the gun-owning community. Do new gun owners, who bought for the first time once COVID-19 began, differ from old gun owners in terms of their political beliefs? If they do, it suggests a potential aggregate shift in the composition of gun owners as a group.

Such a shift could have substantial political implications. Gun ownership is a well-documented driver of individuals’ political views and actions; Joslyn (Reference Joslyn2020), for example, describes a “gun gap” in which gun ownership predicts not only individuals’ gun-related attitudes but also their likelihood of participating in politics, whom they vote for, and their support for capital punishment. Other studies link gun ownership to individuals’ views on race and gender (Filindra, Kaplan, and Buyuker Reference Filindra, Kaplan and Buyuker2021; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Forrest, Lynott and Daly2013; Stroud Reference Stroud2016) and their religious outlooks (Yamane Reference Yamane2016). More broadly, gun owners constitute a crucial and unusually politically engaged group: many gun owners share a highly politically salient social identity that has been central to the mobilizational capabilities of the historically powerful National Rifle Association (NRA) and has helped to cement its prominent position in right-wing politics (Joslyn et al. Reference Joslyn, Haider-Markel, Baggs and Bilbo2017; Lacombe Reference Lacombe2019; Reference Lacombe2021; Lacombe, Howat, and Rothschild Reference Lacombe, Howat and Rothschild2019). With the NRA experiencing substantial organizational challenges that pre-date the disturbances of 2020, the year’s gun-buying surge has the potential to either undermine or buttress it moving forward.

For all of these reasons, there has been speculation about how 2020 may have changed (or not changed) the composition of the gun-owning community. Much of this commentary has focused on anecdotal reports of increased gun buying among Black Americans and women, demographics not typically associated with gun ownership (see, e.g., Alcorn Reference Alcorn2020; Fanaeian Reference Fanaeian2021; Linthicum Reference Linthicum2020; O’Rourke Reference O’Rourke2020; Traylor, Smith, and Tomlin Reference Traylor, Smith and Tomlin2020; Yamane Reference Yamane2021; Young, Andone, and Kirkland Reference Young, Andone and Kirkland2021). If such trends are indeed borne out by the data, one implication could be that new gun owners will politically moderate the population of gun owners. Whether this is the case, however, is yet to be seen—and, in fact, we suggest otherwise.

We theorize that the disturbances of 2020 and into 2021 generated threats that motivated many individuals to purchase guns for the first time.Footnote 1 As a result of having been disproportionately motivated by feelings of threat, we argue that the year’s new gun buyers are compositionally distinct from pre-existing gun owners; that is, whereas the pre-existing buyers include gun hobbyists (e.g., hunters and target shooters) and individuals motivated by threat, new buyers are disproportionately comprised of those driven by threat. This is important, as threats have implications for individuals’ political beliefs. In this case, we turn to work that reveals the connection between threat, on the one hand, and on the other, the holding of conspiratorial or anti-system beliefs. Consequently, and contrary to speculation, we expect that 2020’s new gun buyers are more likely to hold such beliefs than individuals who already owned firearms, thereby altering the shape of the gun-owning community to include more people suspicious of the system.

We test our expectations with a large survey of more than 7,000 gun owners, in which we differentiate first-time and pre-existing owners, and examine their views across several relevant outcomes. The results confirm our expectations: gun buying in general during 2020 correlates significantly with diffuse threat variables such as having COVID-19 in one’s household and experiencing economic hardship. More importantly, we find that new gun owners, compared to pre-existing ones, are more likely to hold conspiracy beliefs and less likely to trust governmental institutions.

Overall, our findings contradict extant narratives that the gun-buying spike of 2020 might moderate the population of gun buyers. Instead, we find that new gun owners’ views differ from those of pre-existing gun owners, but this shift moves the views of the group as a whole in a more, not less, extreme direction. The shift we identify has palpable implications for democracy, given that gun owners, as a group, have the means to act violently against the state—or against fellow citizens whom they associate with it. While we strongly emphasize caution in imputing motives to any gun owners, other research suggests a link between conspiratorial beliefs and the endorsement of violent behaviors (e.g., Baum et al. Reference Baum, Druckman, Simonson, Lin and Perlis2022; Jolley and Paterson Reference Jolley and Paterson2020; Lamberty and Leiser Reference Lamberty and Leiser2019). More generally, the distinct beliefs of new gun owners can alter the composition of the gun-owning population, making them, on average, less trustful and more conspiratorial. Given the political power of those who represent gun owners, this could shift the preferences they channel into government and the relationship between gun owners and governmental institutions. Our findings also accentuate how disturbances that produce feelings of threat can not only impact preferences but also the composition of groups themselves.

Understanding Gun Purchases during Threatening Times

Feelings of threat often provoke action. When people feel threatened, they can become anxious and respond in ways that they believe can minimize danger (e.g., Reiss et al. Reference Reiss, Leen-Thomele, Klackl and Jonas2021). This has been demonstrated in individuals’ attitudes across multiple domains, including climate change (Stollberg and Jonas Reference Stollberg and Jonas2021), terrorism (Sloan et al. Reference Sloan, Haner, Cullen, Graham, Aydin, Kulig and Jonson2021), immigration (Quillian Reference Quillian1995), race (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014), penal response (Klar Reference Klar2013), personal health (Horner et al. Reference Horner, Sielaff, Pyszczynski and Greenberg2021), and more. Most relevant to our paper, purchasing a gun is also a documented response to threat; Sloan et al. (Reference Sloan, Haner, Cullen, Graham, Aydin, Kulig and Jonson2021), for example, show that fear of Muslim terrorist attacks increases the likelihood of buying a firearm. In fact, a wide range of scholarship links gun ownership to different types of threats—including status threats related to race, gender, and socioeconomic well-being (Carlson Reference Carlson2015; Carlson and Goss Reference Carlson and Goss2017; Melzer Reference Melzer2009; Stroud Reference Stroud2012)—and demonstrates that gun-rights organizations frame firearms as needed in response to the threat of victimization (Merry Reference Merry2016; Reference Merry2020).

Stroebe, Leander, and Kruglanski (Reference Stroebe, Leander and Kruglanski2017) offer a theory of gun purchasing that posits the impact of both specific threats, such as victimization, as well as diffuse threats that come from a belief that the world is dangerous and unpredictable (see also Warner and Thrash Reference Warner and Thrash2019). Diffuse threats induce fear that causes unease about the social order (Jackson Reference Jackson2006). Along these lines, Warner (Reference Warner2020, 12), in her study of the motivations of gun ownership, states that, in general, “fear of crime [is] rooted more broadly in abstract anxieties about modernization, reflecting diffuse anxieties brought on by social and economic changes, and perceptions of the world as chaotic and out of control.” This coheres with Carlson’s (Reference Carlson2015) finding that gun carriers conflate crime and economic decline. These diffuse threats can lead to gun buying in order to gain a sense of protection, even if the purchasers do not consciously identify the source of anxiety, such as whether it concerns crime, economic challenges, or some other source (Warner Reference Warner2020).

These types of sentiments likely help to explain the unprecedented spike in gun purchases that occurred during 2020. In fact, from the perspective of the work on gun purchasing, it is somewhat unsurprising that the generally threatening atmosphere experienced by Americans in 2020 led to gun buying. The pandemic introduced a range of novel threats, including health threats from the virus itself and economic threats due to widespread hardship (see, e.g., Perlis et al. Reference Perlis, Santillana, Ognyanova, Green, Druckman, Lazer and Baum2021), which together (and in conjunction with protest events and political turmoil) appear to have motivated individuals to purchase firearms. Given the variety and magnitude of the threats Americans faced, the fact that increased firearm background checks in 2020 dwarfed prior gun-buying episodes rather clearly reflects a perception of guns as a source of safety from a broad sense of peril (Lang and Lang Reference Lang and Lang2021; see also Kerner et al. Reference Kerner, Losee, Higginbotham and Shepperd2022). Therefore, to say that the initial gun-buying surge in April 2020 (and among households sick with COVID-19) was fueled by the pandemic is not to imply that purchasers bought a gun to fight a virus. Rather, fear of death and illness, combined with layoffs and shortages of essential household products, created a generalized or diffuse anxiety that, in turn, fueled gun buying. Operationally, we focus on illness (i.e., COVID-19), which others use to capture threat (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021), and economic hardship. This aligns with documented understandings of the pandemic’s consequences: “in 2020 we encountered COVID-19, which has devastated health and economic activity” (Kaplan, Lefler, and Zilberman Reference Kaplan, Lefler and Zilberman2022, 477; see also Chen et al. Reference Chen, Vullikanti, Santos, Venkatramanan, Hoops, Mortveit and Lewis2021).

Extending this line of thinking, we argue that a surge in threat-motivated gun purchases, especially of the size that occurred in 2020, will affect the composition of gun owners as a group in important ways. To see why, consider four points. First, during less troubling times, a nontrivial number of people buy guns for reasons orthogonal to threat, most notably for hunting and target shooting; a 2017 poll, for example, found that 38% of gun owners reported hunting and 30% reported sport shooting as their reasons for ownership (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Horowitz, Igielnik, Oliphant and Brown2017).Footnote 2 Second, we expect that during COVID-19, feelings of threat likely played an outsized role in gun purchases. Those who bought guns during COVID-19, we argue, often did so due to a diffuse sense of threat brought on by health and economic concerns. Third, if threats induced by 2020 played a large role in motivating gun purchases, it then follows that the group of individuals who bought guns for the first time during COVID-19 will, compositionally, be comprised of a greater proportion of individuals who were motivated by threat than the larger population of gun owners (a substantial proportion of whom have bought firearms, at least in part, for hobbyist reasons). Fourth, these new gun buyers—because their purchases were motivated by threat to an unusual degree—will then be more likely than prior gun owners to hold other beliefs that are correlated with threat. As a result, the arrival of these new gun owners into the gun-owning community will alter the overall composition of beliefs within that community moving forward.

These “other” beliefs include those related to conspiracies: beliefs that seek to explain an event by invoking the machinations of powerful people who attempt to conceal their role while pursuing malevolent goals (Bale Reference Bale2007; Sunstein and Vermeule Reference Sunstein and Vermeule2009). Conspiracy ideation comes in many guises; for example, believing that NASA faked the moon landing or that the government suppressed evidence that the MMR vaccine causes autism. Conspiracy beliefs are by no means a novel societal feature (van Prooijen and Douglas Reference van Prooijen and Douglas2017); however, concern about them has ostensibly increased. This may stem from a growing evidentiary base that shows their breadth (e.g., Oliver and Wood Reference Oliver and Wood2014), as well as their role in contributing to deleterious outcomes such as violence (e.g., Baum et al. Reference Baum, Druckman, Simonson, Lin and Perlis2022, Jolley and Paterson Reference Jolley and Paterson2020, Lamberty and Leiser Reference Lamberty and Leiser2019), the flouting of public health guidelines (e.g., Romer and Jamieson Reference Romer and Jamieson2020; Sternisko et al. Reference Sternisko, Cichocka, Cislak and Van Bavel2021), and the pursuit of political power by candidates for office who support QAnon (Enders et al. Reference Enders, Uscinski, Klofstad, Wuchty, Seelig, Funchion, Murthi, Premaratne and Stoler2022).

People often adopt conspiracy beliefs when they feel a lack of control, which leads them to illusory and accessible narratives that offer explanations that reduce anxiety and provide a sense of increased control (Landau, Kay, and Whitson Reference Landau, Kay and Whitson2015; Levinsson et al. Reference Levinsson, Miconi, Li, Frounfelker and Rousseau2021; van Prooijen Reference van Prooijen2019; van Prooijen and Douglas Reference van Prooijen and Douglas2017). Threatening events, such as natural disasters and disease outbreaks, constitute a primary catalyst for people feeling less control. Šrol, Mikušková, and Čavojová (Reference Šrol, Mikušková and Čavojová2021, 721) capture this dynamic, explaining that individuals “take a complex event—for example, an outbreak of a deadly virus—and provide an explanation of the event and someone to blame for it…” which indicates that “conspiracy theories may satisfy important epistemic motives, that is, the need to understand what is happening around us, as well as existential motives to regain the feeling of control, security, and meaning in the world after encountering some threatening event.”Footnote 3 Related to 2020’s events, Šrol, Mikušková, and Čavojová (Reference Šrol, Mikušková and Čavojová2021) show that perceptions of COVID-19 risk and a concomitant lack of control predicts COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, as well as more generic conspiracy and pseudoscientific beliefs (i.e., it is not domain specific) (see also Jutzi et al. Reference Jutzi, Willardt, Schmid and Jones2020; Scrima et al. Reference Scrima, Miceli, Caci and Cardaci2022). The embracing of more general conspiracy beliefs, beyond those of the specific threatening events, reflects how conspiratorial thinking becomes a part of one’s identity that often spans across multiple issues (Lewandowsky, Gignac, and Oberauer Reference Lewandowsky, Gignac and Oberauer2013, 630; Oliver and Wood Reference Oliver and Wood2014, 954, 958; Uscinski and Parent Reference Uscinski and Parent2014).

We use these findings to posit a distinction between new and old gun owners. Since the group of new gun buyers will be composed of more individuals driven by threat due to the pandemic and economic strain, they will also be more likely to accept both COVID-19 specific and general conspiracy theories. Our first hypothesis, then, is as follows:

-

• Relative to those who previously owned guns, gun buyers who purchased firearms for the first time during 2020–21 will be significantly more likely to hold specific COVID-19 and general conspiracy beliefs, all else constant (hypothesis 1).

Threat also relates to anti-system beliefs and trust. When citizens attribute a threatening situation to governmental actors, their trust in those actors declines—they are unable to trust those whom they see as having caused the threat (e.g., Albertson and Gadarian Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015; Schlipphak Reference Schlipphak2021). This explains why partisans who particularly dislike or feel threatened by the other party become distrustful of government when that party wins office (Hetherington and Rudolph Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2015). Building on our prior point, if more first-time gun buyers bought due to threat, it follows that they will express less trust in institutions than those who already owned them. Similarly, the increased conspiracy beliefs among these new gun owners (as suggested by hypothesis 1) mean they likely have less faith in institutions (i.e., they attribute institutional failure as a source of the threat). In our case, this includes health and scientific institutions (which may be seen as having failed to adequately handle COVID-19) as well as media institutions (which may be seen as having misled the public about the pandemic and other relevant matters). This leads to our second hypothesis:

-

• Relative to those who previously owned guns, gun buyers who purchased firearms for the first time during 2020–21 will, all else constant, be significantly less trusting of

health institutions (hypothesis 2a),

scientific institutions (hypothesis 2b), and

media institutions (hypothesis 2c).

Importantly, our hypotheses, if confirmed, would be all the more notable given that the population of pre-existing gun owners would themselves be expected (relative to the general public) to hold the sorts of views on which we focus. That is, our hypotheses about the attitudes of new gun owners are not meant to imply that pre-existing owners are unlikely to hold conspiratorial views about 2020’s events and anti-system sentiments about actors and institutions that played central roles in those events. Rather, we expect pre-existing gun owners (all else equal) to be more likely to hold such views than other Americans, given their low trust in government (Jiobu and Curry Reference Jiobu and Curry2001), perceptions of media bias (Zhang and Lin Reference Zhang and Lin2022), and their tendency to embrace a right-wing populist worldview (Lacombe Reference Lacombe2021). Our theoretical framework and associated hypotheses, however, lead us to expect that first-time gun owners will shift the broader gun-owning community even further in this direction, reinforcing and extending the sorts of extant attitudes that have been shown to be associated with gun ownership.

Data and Methods

We recruited respondents through the PureSpectrum survey platform (https://www.purespectrum.com/) that aggregates and deduplicates panelists from multiple sources (see online appendix A). The data, which were collected between April and July of 2021, are quota-sampled on demographic benchmarks and weighted to reflect the US population along dimensions of race/ethnicity, gender, age, education, geographic region, and zip-code urbanicity.Footnote 4 To minimize topical selection bias, we did not inform respondents of the purpose of the survey when they entered it, and questions covered a broad range of topics, mostly related to public health. We filtered out inattentive and semiautomated respondents through multiple closed- and open-ended attention checks. Emerging evidence suggests this general approach to data collection can perform as well as traditional probability sampling (Enns and Rothschild Reference Enns and Rothschild2021; Lehdonvirta et al. Reference Lehdonvirta, Oksanen, Räsänen and Blank2021; Radford et al. Reference Radford, Green, Quintana, Safarpour, Simonson, Baum and Lazer2022).

Our full sample (after filtering) includes 24,448 unique respondents; in online appendix A, we provide a table containing descriptive statistics of the sample. The notably large sample ensured that we would have a sufficient number of old and new gun owners to test our hypotheses.Footnote 5 Specifically, our analyses that compare gun owners to other Americans use the full sample, while our analyses comparing pre-existing and new gun owners focus on a subset of respondents (n = 7,699) who reported being gun owners. We consider pandemic (or “2020”) gun buyers to be those who bought guns in or after March 2020, when COVID-19’s presence in the US began to rapidly increase, a national emergency was declared, and states throughout the country issued stay-at-home orders. Pre-existing gun owners are those who, regardless of whether they made pandemic purchases, owned guns prior to March 2020, while first-time buyers are those who bought guns during or after March 2020 and did not, prior to that point, own any. In our sample, 7,350 respondents were pre-existing gun owners (of whom 1,483 bought additional guns in the pandemic) while 349 were first-time gun buyers.Footnote 6 To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first such analysis comparing old and new gun purchasers.

Our analyses proceed in two parts. We first examine the relationship between threat and 2020 gun buying. We do this to assess the underlying premise of our theory that pandemic gun buyers were motivated by threats caused by the events of 2020. To examine gun-buying decisions, we use as our dependent variable a question asking respondents whether they or a member of their household purchased a gun during the pandemic (see online appendix B for exact wording).Footnote 7 We use linear probability models with robust standard errors to examine the effect of a number of factors (independent variables) on gun purchasing.Footnote 8 We theorize that the pandemic disturbance introduced health threats (from the virus) and economic threats (stemming from shutdowns), which, in turn, produced a diffuse sense of threat. Our measures asked respondents whether anyone in an individual’s household was diagnosed with COVID-19 and, separately, whether they experienced economic hardships during the pandemic. To be clear, we do not mean to suggest that individuals consciously or explicitly connected these experiences to gun purchasing; rather, we argue that these experiences generate a sense of diffuse threat (or anxiety) that leads one to take action in response. (In the final section of our analysis, we offer some insight into individuals’ explicitly offered rationales for buying guns.)

We include a range of other variables that might affect pandemic gun purchasing, including partisanship, parental status, race, community type (rural, urban, or suburban), whether the respondent is a white evangelical Christian (which has been shown to be linked to gun ownership and attitudes; see Merino Reference Merino2018; Yamane Reference Yamane2016), income, ideology, college education, gender, and age. We also control for prior gun ownership (which, as a predictor of future gun purchases, is important to hold constant in order to identify the impact of threat), and region-fixed effects. In this first set of tests, we expect to find that pandemic gun buying is predicted by each of our variables capturing threat (i.e., economic hardships and household COVID diagnoses). To be clear, we expect this to be the case for all individuals, including those who did and did not own guns prior to the pandemic.

The second part of our analysis shifts to our core hypotheses regarding conspiracy beliefs and institutional trust. Here, we compare new and pre-existing gun owners to examine the extent to which their views differ. We do this in two different ways; first, by comparing new gun owners to all pre-existing gun owners (regardless of whether those pre-existing owners bought additional guns during the pandemic) and, second, by comparing new gun owners to pre-existing owners who did not buy more guns during the pandemic. We also, as a point of reference, compare pre-existing gun owners to non-gun owners (i.e., those who did not own guns before the pandemic and did not buy them during it), which provides a baseline measure of the views of those who owned guns prior to the pandemic. These analyses give important context, as they speak to where gun owners as a social group stood prior to the entry of first-time buyers into the gun-owning community; the substantive consequences of differences and similarities between the views of new and pre-existing gun owners depends on the nature of pre-existing gun owners’ views. In other words, the consequences of our main findings, which compare new gun owners to pre-existing owners, depend in part on how likely pre-existing owners are to hold conspiracy beliefs and how trusting they are of institutions.

To test our first hypothesis, we look at two dependent variables that measure conspiracy beliefs. The first captures whether individuals believe that the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump (see Graham and Yair Reference Graham and Yair2021 regarding the depth and stability of this belief as reported in surveys). This emerged as one of the most-discussed conspiracies in recent times insofar as it emphasized powerful people (e.g., Democrats, media, election officials) hiding their actions to achieve the problematic goal of undermining a democratic election (DiMaggio Reference DiMaggio2022, 9). The second dependent variable is an additive index capturing conspiratorial views about COVID-19 vaccines; this consists of four items pertaining to whether the respondent believes that vaccines change people’s DNA, contain microchips, incorporate lung tissue from aborted fetuses, or cause infertility (α = .69). For each item, respondents were asked about the statement with answer options being “accurate,” “inaccurate,” or “not sure.” An answer of “accurate” counts as a conspiracy belief. We selected the vaccine-specific statements based on Google searches for prevalent conspiracies at the time and perusal of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website section on common myths. We also included a fifth true item (that the vaccine has been thoroughly tested), reverse-coded such that the variable takes on the value of one if the respondent does not indicate it is true that the COVID-19 vaccines were tested on thousands of people in clinical trials.

To test our second hypotheses (2a, 2b, 2c), we examine several dependent variables pertaining to trust in institutions. The goal is to identify whether first-time buyers have less faith in the “system” than pre-existing gun owners—including health, science, and media institutions. These are particularly crucial items given the role of these entities in providing information, generally, but also specifically during COVID-19. As Latkin et al. (Reference Latkin, Dayton, Strickland, Colon, Rimal and Boodram2020, 764) state, it “is essential that the public have a trustworthy source of COVID-19 information, as the pandemic has caused massive disruptions and threats to the health of entire populations.” Trust in science and health institutions played a substantial role in COVID-19 reactions, such as in the willingness to be vaccinated (Jamieson et al. Reference Jamieson, Romer, Jamieson, Winneg and Pasek2021). Moreover, partisan polarization in the United States during COVID-19 stemmed, in part, from variation in individuals’ trust in health institutions (Hegland et al. Reference Hegland, Zhang, Zichettella and Pasek2022) and the media (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wu, Crimmins and Ailshire2020). Our precise items follow other work by asking respondents to report how much they trust health officials (specifically, the Food and Drug Administration, CDC, and Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health combined into an index) (α = .88), scientists and researchers, and the news media to do the right thing in handling COVID-19, all scored on four-point scales from “not at all” to “a lot” (see, e.g., Hamilton and Safford Reference Hamilton and Safford2021; Jamieson et al. Reference Jamieson, Romer, Jamieson, Winneg and Pasek2021; Latkin et al. Reference Latkin, Dayton, Strickland, Colon, Rimal and Boodram2020). In all models, we use the same set of controls as in the previous analyses, while also holding constant household COVID-19 diagnoses and economic hardship. (See the online appendix B for all key question wordings.)

Beyond their obvious relevance to the events of 2020, we believe our variables pertaining to conspiracy beliefs and trust are particularly useful for testing our hypotheses because they are not directly related to gun politics; in other words, rather than looking at trust in, for example, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (which enforces most federal gun laws) or beliefs in conspiracies pertaining to gun confiscation, we instead examine outcomes that constitute a tougher and more generalizable test of our argument. Generally, the combination of low trust in knowledge-providing institutions, conspiracy beliefs, and first-time gun buying could alter the composition of the gun-owning population, pushing it in a more extreme direction.

Results

We begin by examining the extent to which a sense of diffuse threat generated by anxiety-inducing experiences in 2020—measured by variables capturing economic hardship and household COVID-19 diagnoses—predicts gun buying. We do this prior to testing our main hypotheses to confirm our assumption that variables connected to threat are related to gun buying. We also include the other covariates, which are ordered by the size of their effects.Footnote 9 As expected, our threat variables are indeed important predictors of pandemic gun buying; as figure 1 shows, both household COVID-19 and our economic hardship index are positive and statistically significant.Footnote 10 Interestingly, we also find that, all else constant, parents are more likely to buy guns during the pandemic; this is consistent with our argument about threat, as pandemic-related disruptions to society may have impacted parents particularly strongly (given both their childcare needs and the financial costs of supporting a family). Notably, our findings contradict the aforementioned anecdotal reports about the demographics of the gun-buying surge; when controlling for other factors, being Black is not a significant predictor of pandemic gun buying and the female coefficient is actually negative. Finally, we find that several other factors that would theoretically be expected to predict gun buying are also significant, including Republican party identification.Footnote 11 Taken together, these findings are consistent with the notion that the gun-buying spike of 2020 was motivated by diffuse threat, leading, as we show next, to a more mistrustful, conspiracy-fearing population of gun owners than before.

Figure 1 Marginal Probability of Purchasing a Gun During the Pandemic

Comparing the Views of Pre-Existing and New Gun Owners

We now turn to our primary hypotheses, which pertain to differences between the views of pre-existing and new gun owners. Our first hypothesis is that new gun owners will be more likely than pre-existing gun owners to hold conspiracy beliefs. These include, first, a belief that Trump was the true victor in the 2020 election, and, second, belief in conspiracy theories about the nature and effects of COVID-19 vaccines, such as whether they alter people’s DNA or contain microchips (which we combine into an additive index).

Our findings are depicted in figure 2, where we display three comparisons from models that can be found in full form in online appendix C. Specifically, we include results that compare pre-existing gun owners to nonowners. These are important for interpreting the substantive meaning of both differences and similarities between new and pre-existing owners. As noted, we expect pre-existing owners to be more likely to hold conspiratorial views than the general public. We then present two tests of hypothesis 1, which posits that new gun buyers will be more likely to hold conspiracy beliefs than those who previously owned guns: one set of results includes a comparison against all pre-existing gun owners (perhaps the strictest test of our hypothesis) while the other focuses on new gun buyers relative to old gun buyers who did not buy during the pandemic. This second comparison is interesting since those who did not buy at all were likely less motivated by threat and thus are even less likely to hold conspiratorial views. Each panel includes results for the 2020 election conspiracy, the vaccine conspiracy index, and each individual vaccine conspiracy item.

Figure 2 Conspiracy Beliefs Among Existing and New Gun Owners

The first panel of figure 2 shows that pre-existing gun owners, compared to all other respondents, are statistically significantly more likely both to believe that Trump won the 2020 election and to hold conspiratorial views about COVID-19 vaccines. These findings are expected given prior work on the political views of gun owners (see, e.g., Joslyn Reference Joslyn2020; Lacombe Reference Lacombe2021). What about new gun owners? The second panel of figure 2 shows partially consistent evidence with regard to the 2020 election: new gun owners are more likely to believe the conspiracy compared to pre-existing gun owners, although it does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p = 0.14). Moreover, given how strongly pre-existing gun ownership predicts a belief that Trump was the election’s true victor (the first panel), a nonfinding here is still notable as it suggests that first-time gun owners, rather than moderating the views of others in the gun-owning community, are (at the very least) just as likely to believe the election was stolen.

In the case of vaccine views, we see (as predicted) that first-time gun buyers are significantly more likely to hold conspiracy beliefs than pre-existing gun owners, who themselves were already more likely than other respondents to hold such beliefs. This is the case for the scale as well as several of the individual items (while those that are not statistically significant at conventional levels are nonetheless positive). This is clear support for hypothesis 1: the entry of new buyers into the ranks of gun ownership pulls an already conspiratorial group in a more conspiratorial direction. This is accentuated by the last panel, where we see even stronger effects when comparing new gun buyers against pre-existing owners who did not buy during the pandemic.

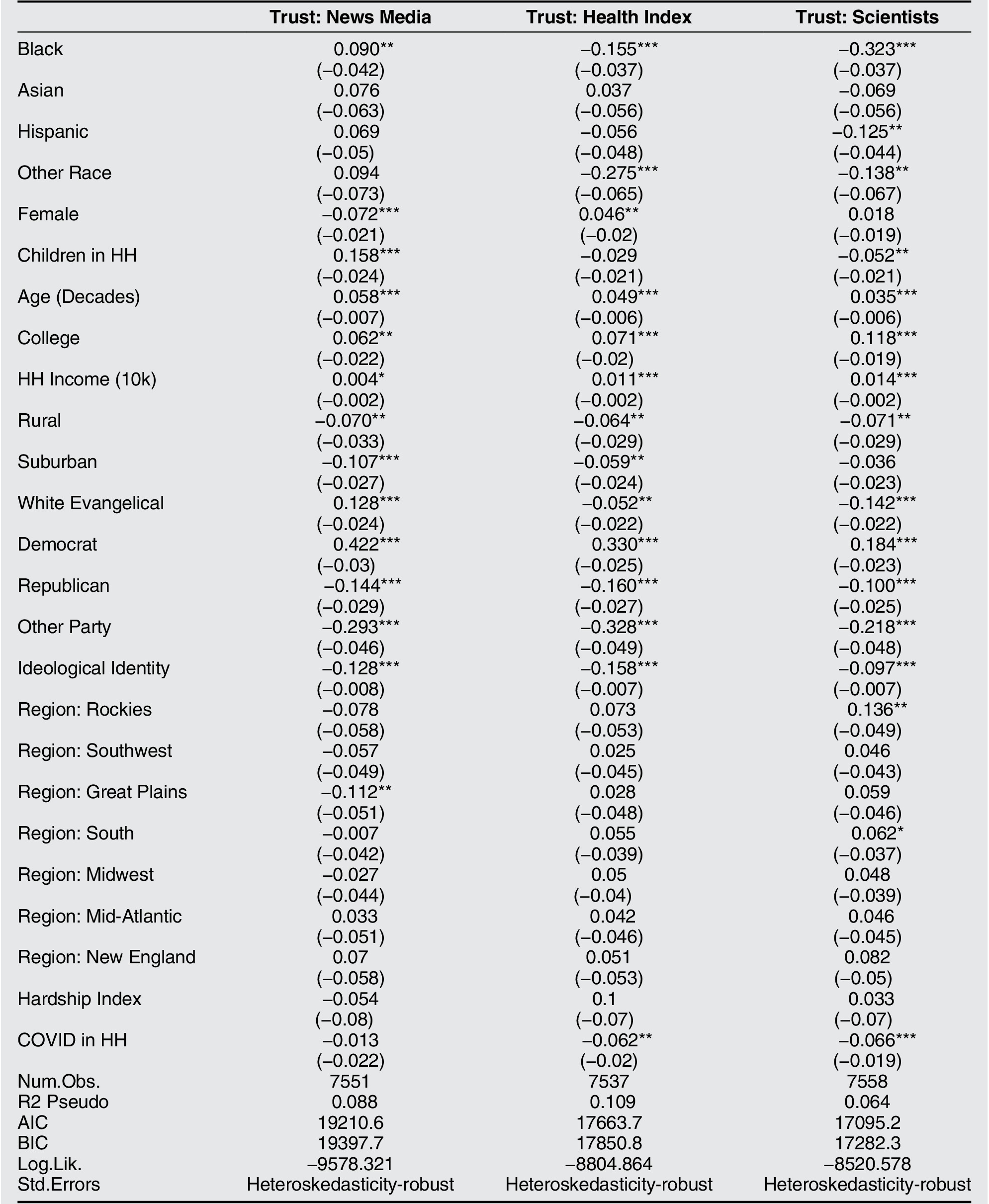

We now turn to our second hypothesis, which is that new gun owners will be more likely to hold anti-system views than pre-existing gun owners. We measure such views through three different variables pertaining to institutional trust: trust in government health institutions, trust in scientists, and trust in the news media. We present our findings in the same way as we presented those pertaining to hypothesis 1, with the full results appearing in online appendix C. We again see, in the first panel of figure 3, that pre-existing gun owners were less trusting of all three groups than other respondents; this coheres with the well-known political outlooks associated with gun ownership. More notable, however, is that the second panel strongly supports hypotheses 2a, b, and c: first-time gun buyers report substantially less trust than pre-existing gun owners in all three cases. Again, we see that these new gun owners pull an already low-trust group in an even less trusting direction. The final panel shows that relative to existing owners who did not buy during the pandemic, new owners also exhibit substantially less trust.

Figure 3 Institutional Trust Among Existing and New Gun Owners

Taken all together, the findings presented in this section align with our argument. We examine five different relevant outcomes (as well as the component parts of the vaccine conspiracy index) and in four cases our findings confirm our hypotheses; in the fifth case, which pertains to the 2020 election, we find that new gun owners are no less likely than prior gun owners to hold the conspiratorial belief that Trump was the true victor and, indeed, that they are more likely to do so at the p < 0.14 significance level. Further, they are significantly more likely to hold that belief than pre-existing owners who did not buy during the pandemic.

Robustness Checks

We conducted two different types of checks to assess the robustness of our findings. The first further probes the stated motivations of gun buyers, focusing on the relationship between threat and first-time purchases. Recall that our earlier analyses looked at how anxiety-inducing events created diffuse feelings of threat that correlate with gun buying. The theoretical work on which we build makes clear that individuals do not necessarily need to consciously connect these diffuse feelings to explicitly articulated rationales for buying guns. We can nonetheless look to such rationales for additional information because our data include a question that asked those who purchased guns during the pandemic their reasons for doing so. The response options include both hobbyist reasons—hunting and target shooting—and reasons that can be connected to threats, such as protection from crime.Footnote 12 Respondents could select all that apply. To be clear, this question was asked only of those who bought guns during the pandemic, which means that it excludes pre-existing gun owners who did not make additional purchases during or after March 2020; as a result, the sample used for analyses that include this question differs from the samples used in other parts of the paper. Nonetheless, it provides some useful insight into the reasons that people provided for buying guns.

Earlier, we showed that all 2020 gun buyers were more likely than the rest of the public to have faced threat-inducing events—namely, economic hardships and COVID-19 in the household. Yet, while elevated threats were associated with gun purchases by new and pre-existing owners alike, threats were more likely to be the stated rationale for purchase among first-time buyers. This is shown in figure 4, which plots coefficient estimates of being a new gun owner (as opposed to a pre-existing gun owner) from separate regressions that take different reasons for purchasing guns—threat-based reasons, hobby-based reasons, and other reasons—as their outcome (i.e., we ran a distinct regression for each of those reasons). We find that new gun owners attributed their purchases to threat-based motivations more frequently than pre-existing owners, while pre-existing owners were more likely to cite hunting and target-shooting, reasons that were already popular before the pandemic (see Parker et al. Reference Parker, Horowitz, Igielnik, Oliphant and Brown2017). Thus, this influx of threat-driven buyers suggests that gun owners as a group are probably now more threat-driven than before the pandemic.Footnote 13 Note that, because we did not pose this question to pre-existing gun owners who did not purchase additional guns during the pandemic, the differences we identify between first-time and repeat gun buyers here very likely understate gaps between new and pre-existing owners.Footnote 14 Although we expect (and find) that all pandemic gun buyers were motivated by diffuse senses of threat, our finding here, with gun owners articulating their reasons for buying, lends support to the notion that the composition of first-time gun buyers is consciously motivated to an unusual degree by threat.

Figure 4 Reasons for Purchasing Guns During the Pandemic

Second, we also include a robustness check that pertains to our core hypotheses regarding the views of gun owners. Here, we explore the same dependent variables about conspiracy beliefs and trust but focus on the independent variables that are associated with diffuse threat (while including the same control variables as we have throughout the paper).Footnote 15 We do this by limiting the sample to all gun owners (i.e., first-time buyers, those who owned guns before the pandemic and bought more during it, and those who owned guns before the pandemic but did not buy more during it) and examining factors that would be linked with anxiety due to the pandemic. These are whether anyone in an individual’s household was diagnosed with COVID-19 and whether an individual experienced pandemic-related financial hardships. We expect to find that household COVID-19 cases and economic hardship predict conspiracy beliefs and trust; our theory is that threat motivates both gun buying and the attitudes that we examine, which means our threat variables should predict our dependent variables. As tables 1 and 2 (which present the key independent variables; full tables are in online appendix C) show, this is indeed what we find. Both outcomes related to conspiracy beliefs are predicted by either household COVID-19 or the economic hardship index (or both), as are two of the three trust outcomes (with the remaining item going in the expected direction). As we already saw in the middle panels of figures 2 and 3, being a new gun owner is significantly associated with reduced levels of trust and the vaccine conspiracy index (with new gun ownership positive but not significant in the Trump conspiracy model).

Table 1 Correlates of Conspiracy Beliefs (All Owners)

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001

Table 2 Correlates of Institutional Trust (All Owners)

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001

These findings, in conjunction with our other findings, show that threat-based gun buyers differ from others, which indicates that the composition of the population of gun owners—as a result of the entry of a group of first-time gun buyers especially motivated by threat—has shifted during the pandemic, with a greater proportion holding conspiracy beliefs and reporting low levels of trust in important institutions.

Discussion

In this study, we have examined how the gun-buying surge of 2020—by bringing many millions of new Americans into the gun-owning community—may alter the group composition of gun owners moving forward. Gun owners are a notably important group, for at least two reasons. First, gun owners have been shown to be a crucial political constituency; participating in politics at unusually high rates, holding a distinct set of views, and comprising a key part of the Republican Party’s electoral coalition, gun-owning Americans—led by the NRA—have played a large role not just in the realm of gun politics but in US politics more broadly. As a result, potential shifts in their political beliefs are important for both substantive and academic reasons. Second, gun owners are important because, by definition, they are armed: they possess the ability—at least to some extent—to address security concerns independently of the state and, indeed, even the potential to take on the state. As a result, their political attitudes and actions, particularly those that pertain to conspiracy beliefs and anti-system views, have clear implications for American democracy.

In this light, we believe our findings are consequential. We demonstrate that the gun-buying spike of 2020 was motivated in large part by threat, which prior work has shown to be associated with a distinct set of political views. We examine whether 2020’s gun buyers—particularly its first-time buyers who, by virtue of being new to the group, have the capacity to alter its composition—hold these views; we focus in particular on attitudes pertaining to the 2020 election and COVID-19 vaccines, along with trust in public health, science, and media institutions. We find that new gun owners are, in almost all cases, more likely than pre-existing gun owners to hold conspiracy beliefs and anti-system views, even despite the fact that pre-existing gun owners, relative to other Americans, are themselves more likely to hold such attitudes. In other words, our evidence contradicts the claims of some that first-time gun buyers will substantially moderate the sociopolitical meaning of gun ownership in the US. Rather, we find that the new gun owners of 2020 hold views that are more extreme than those of pre-existing gun owners. Importantly, since new gun owners have beliefs that directionally echo those of prior owners (when viewed relative to the general population), they are unlikely to cause a fissure with the pre-existing population of gun owners, instead moving the group in a further conspiratorial and anti-system direction.

Along these lines, 2020 led to an increase in the number of people who have the means to act against the state. To date, gun owners as a group have not moved against the state; however, in light of our results and other work that links conspiracy beliefs to support for violence (e.g., Baum et al. Reference Baum, Druckman, Simonson, Lin and Perlis2022; Jolley and Paterson Reference Jolley and Paterson2020; Lamberty and Leiser Reference Lamberty and Leiser2019), an important next step would be to examine whether a direct relationship exists between gun buying and support for, and engagement in, political violence. Interestingly, in additional analyses, we find that new gun owners do not express greater out-party animosity or affective polarization relative to pre-existing gun owners. Other work, though, indicates that polarization is not a prerequisite for political violence (Mernyk et al. Reference Mernyk, Pink, Druckman and Willer2022), suggesting instead that the mechanism involves anti-system orientations that envelop conspiracy beliefs (Uscinski et al. Reference Uscinski, Enders, Seelig, Klofstad, Funchion, Everett, Wuchty, Premaratne and Murthi2021). This further accentuates the need to pinpoint additional behavioral correlates of gun buyers, as well as the underlying psychological mechanisms.

Related subsequent work might also explore in greater nuance the question of who bought guns during the pandemic and why. Our finding that parents were more likely to make pandemic gun purchases is somewhat surprising and interesting, as is our finding, contra reports in the press, that women and Black Americans were not more likely to do so. While our theoretical framework led us to focus on the role of threat-generating experiences, additional insights into the mechanisms that drove the gun-buying surge could be enlightening.

Our findings also demonstrate that when individuals take actions that stem from threat, there can be important downstream consequences that are not necessarily obvious. In this case, the events of 2020 caused a number of threats, which in turn motivated gun buying, which in turn has consequences for a number of different political outcomes. Understanding both how threat motivates actions and what sorts of consequences those actions have is thus crucial. More generally, threats typically do not prompt direct calculated actions to address their source. Instead, they often trigger a range of emotions that bias decision making. In the case of gun buying, senses of diffuse threat can prompt gun purchases even when owning guns has no obvious connection to the threat. It also can alter reasoning as people seek attributions and explanations for the threat. In the case of the pandemic, these patterns seemed to connect with both gun buying and anti-system beliefs, a potentially dangerous combination.

Finally, our work adds to classic theories of group politics. Scholars have long recognized groups as the key building blocks of politics (e.g., Dahl Reference Dahl1961; Olson Reference Olson1965; Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960; Tocqueville Reference Tocqueville, Mansfield and Winthrop1835; Truman Reference Truman1951), and have more recently shown how external threat shapes the groups with which people identify (e.g., Greenaway and Cruwys Reference Greenaway and Cruwys2019; Klar Reference Klar2013; Knowles and Tropp Reference Knowles and Tropp2018; Mutz Reference Mutz2018).Footnote 16 We demonstrate that disturbances—that is, social, political, or economic disruptions to the system—do not just encourage the mobilization of “potential groups” comprised of individuals who perceive their shared interests to be threatened, but can also lead to important changes in the composition of existing groups. In other words, when disturbances, such as a global pandemic, make individuals feel threatened, they may respond by entering the ranks of a pre-existing group. This decision has consequences for those who are part of that group and what sorts of views its members hold.

We have explored this pattern in the case of gun owners. A set of threatening conditions caused a surge in gun-buying, including among millions of individuals who did not previously own guns. This led to speculation that the apparent diversity of these new gun owners relative to pre-existing owners would moderate the views of the gun-owning community. Our expectations, built on extant scholarship focused on the effects of disturbances and the threatening feelings they cause, were the opposite, however, and are borne out by our findings: rather than moderating the gun-owning community, the first-time gun buyers of 2020 have instead moved a group that was already especially likely to hold conspiracy beliefs and anti-system views in a more extreme direction. These findings suggest that subsequent work should consider not just how social, economic, and political disruptions mobilize groups, but also how they change the composition of groups that already exist. Such work could help to explain how and why critical junctures caused by threatening events sometimes reorganize lines of group-based political conflict in unexpected ways.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722003322.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Joslyn, Mike Miller, and several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. We acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation under grants SES-2029292, SES-2029297, and SES-2116645, and the Peter G. Peterson Foundation.