Article contents

Ramsey Sentences and the Meaning of Quantifiers

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 April 2022

Extract

1. Ramsey Sentences and the Function of Theoretical Concepts. In his famous paper “Theories,” Frank Ramsey (1931, 212–236; 1978, Ch. 4) introduced a technique of examining a scientific theory by means of certain propositions, dubbed later “Ramsey Sentences.” They are the results of what is often called Ramsey elimination. This prima facie elimination is often presented as a method of dispensing with theoretical concepts in scientific theorizing. The idea is this: Assume that we are given a finitely axiomatized scientific theory

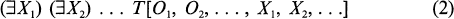

where O1, O2, … are the primitive observation terms (individual constants, predicate constants, function constants, etc.) of (1) and H1, H2, … its primitive theoretical terms. For simplicity, it will be assumed that (1) is a first-order theory. Since it is finitely axiomatizable, we may think of it as having the form of a single complex proposition, i.e., the conjunction of all the axioms. What can then be done is to generalize existentially with respect to (1). The result is a sentence of the form

In (2), the theoretical terms H1, H2, … do not occur any longer. They have been replaced by the variables X1, X2, … bound to initial existential quantifiers. In this sense at least, Ramsey sentences do effect on elimination. Unlike (1), (2) is not a first-order sentence but a second-order one.

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Philosophy of Science Association 1998

Footnotes

Send requests for reprints to the author, Department of Philosophy, Boston University, 745 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02215.

References

- 10

- Cited by