Article contents

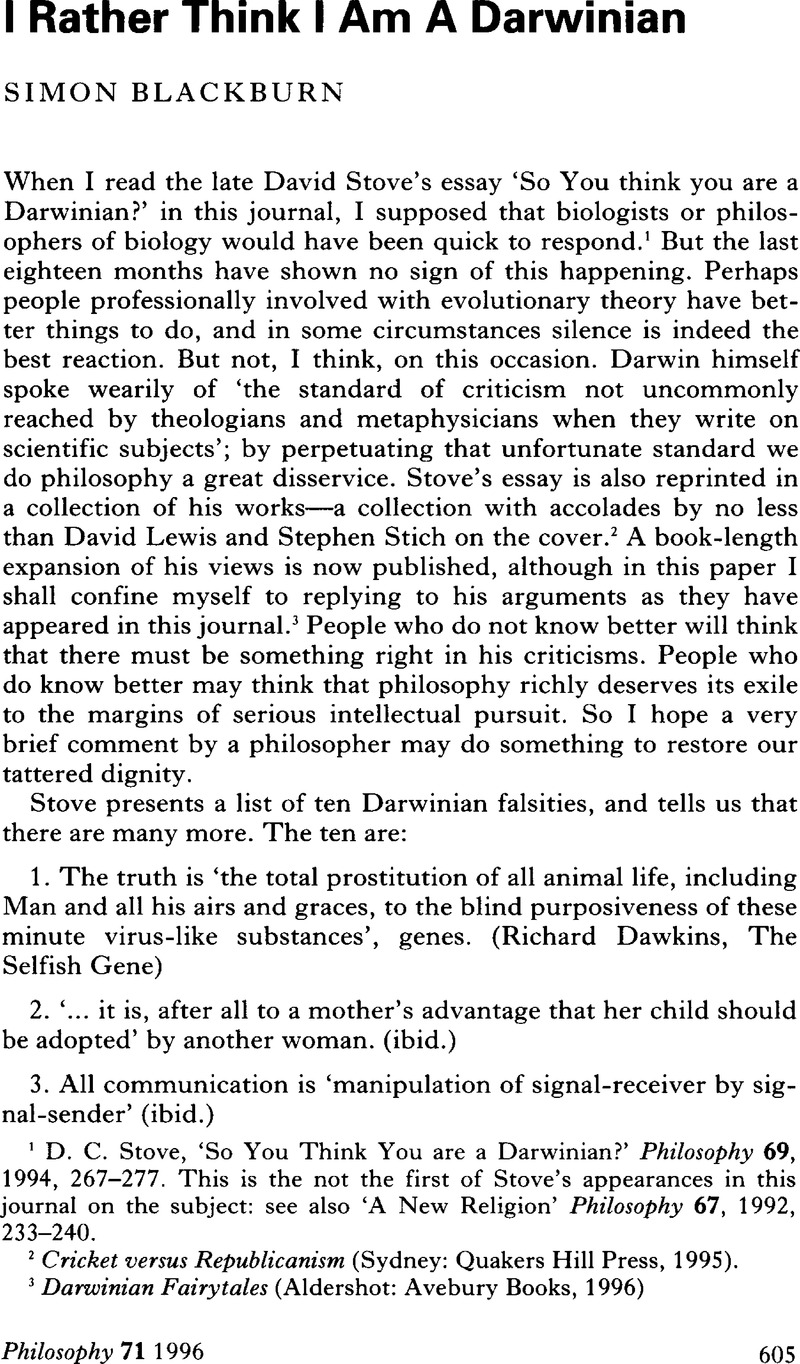

I Rather Think I Am A Darwinian

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 January 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Discussion

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Royal Institute of Philosophy 1996

References

1 Stove, D. C., ‘So You Think You are a Darwinian?’ Philosophy 69, 1994, 267–277.CrossRefGoogle Scholar This is the not the first of Stove's appearances in this journal on the subject: see also ‘A New Religion’ Philosophy 67, 1992, 233–240.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 Cricket versus Republicanism (Sydney: Quakers Hill Press, 1995).Google Scholar

3 Darwinian Fairytales (Aldershot: Avebury Books, 1996).Google Scholar

4 Hamilton, W. D., ‘The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour’, The Journal of Theoretical Biology 7, 1964, 1–52.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

5 Dawkins, R., The Extended Phenotype, (Oxford University Press, 1982), ch 3.Google Scholar

6 Dawkins, R.The Selfish Gene (Oxford University Press, 1976).Google Scholar The quotations are from pp. 200–201 of the 1989 edition. See also p. 332.That Dawkins is in a muddle is evident from the assertion that ‘we, that is our brains, are separate and independent enough from our genes to rebel against them’:a remarkable feat, one would have thought. We don't rebel against our brains by using them. Of course we can think up a sense in which it might be true: we ‘rebel’ against our genetically coded height, for example, every time weclimb a ladder. But in this sense it is not true that we ‘alone on earth’ rebel against our genes. A bear sheltering in a cave is rebelling against its genetically coded tendency to freeze in bad weather, in just the same sense. Like many others, Dawkins was trying, but failing, to derive some sweeping human or philosophical interest from the biology and of course it was the belief that he had done that which gave the book, interesting as it is in its literal science, its wider reputation. This is also why there is something a little disingenuous in simply sheltering behind the claim that words like ‘selfish’ or ‘advantage’, or ‘purpose’ or ‘manipulate’ are being used in a technical sense. If I write and profit from a book on popular biology which I call, say, The Nazi Within, it is a little cheeky of me to say that I was simply using the term ‘Nazi’ in a technical sense in which it means ‘bit of chemical that replicates itself over time’. This is, I think, the real point buried in Midgley's paper (p. 448) that Dawkins failed to answer.

7 Dawkins, R. ‘In Defence of Selfish Genes’, Philosophy 56, 1981, 556–573CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Midgley, M., ‘Gene Juggling’, Philosophy 54, 1979, 439–458. The second and third of Stove's list of Darwinian falsehoods depend upon misreading technical uses of terms ‘advantage’ and ‘manipulation’ as they are used in Dawkins's writings. But see also the previous note.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

8 Trivers, R. L., ‘The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism’. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, 35–37.Google Scholar

9 Trivers, R. L., Social Evolution (California: Benjamin/Cummings, 1985),198–200.Google Scholar

10 The superficiality of the genetic story is scathingly criticized in Not in Our Genes, Rose, Steven, Kamin, Leon, AND Lewontin, R., (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1984), 260–261.Google ScholarPubMed

11 Kettlewell, H., The Evolution of Melanism (Oxford University Press, 1973) is one of the most revered. One wonders what Stove's explanation of the relative frequency of black and speckled moths in town and country would be.Google Scholar

12 I would like to thank James Maclaurin and David Braddon-Mitchell for helpful conversation and biological information.

- 2

- Cited by