1 Introduction

A long-standing question in phonology concerns how the prosodic structure of an utterance both departs from and is constrained by syntax. Match Theory argues for a straightforward mapping from syntactic constituents to prosodic domains, carried out by Match constraints (Selkirk Reference Selkirk, Goldsmith, Riggle and Yu2011). MatchWord maps heads (X0) to prosodic words (ω), MatchXP maps maximal projections (XP) to phonological phrases (φ) and MatchClause maps clauses to intonational phrases (ι). This mapping is schematised in (1).

-

(1)

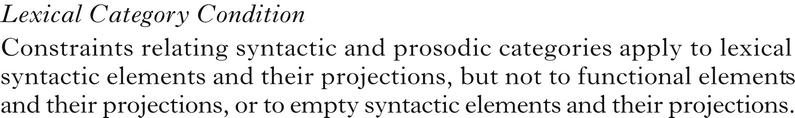

An ongoing debate concerns which syntactic constituents are visible to Match constraints (Elfner Reference Elfner2012, Guekguezian Reference Guekguezian2017, Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2019, Tyler Reference Tyler2019). A distinction is frequently drawn between lexical and functional elements, such that the syntax–prosody mapping only makes reference to lexical XPs (e.g. NP, AP, VP), while ignoring functional XPs (e.g. DP, PP, TP) (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986, Selkirk Reference Selkirk1986, Reference Selkirk, Morgan and Demuth1996, Truckenbrodt Reference Truckenbrodt1999). Truckenbrodt formalises this insight as the Lexical Category Condition, given in (2), which asserts that only XPs with phonologically overt lexical heads are visible to the syntax–prosody mapping.

-

(2)

One line of work has continued to assume a lexical/functional distinction (e.g. Selkirk Reference Selkirk, Goldsmith, Riggle and Yu2011, Ishihara Reference Ishihara2014). Selkirk & Lee (Reference Selkirk and Lee2017) propose MatchPhraseLex, which ports the Lexical Category Condition into Match Theory by requiring MatchXP to ignore functional XPs and XPs with silent heads. Another line of work has reached the opposite conclusion: Elfner (Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015) provides evidence that all XPs, including functional phrases, are visible to MatchXP, and other researchers have adopted this view (Elordieta Reference Elordieta2015, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Elfner and McCloskey2016, Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2019). At the word level, Tyler (Reference Tyler2019) argues that a strict lexical/functional distinction does not adequately account for the idiosyncratic behaviour of function words: some function words are prosodically dependent, while others form prosodic words. Tyler proposes that all heads are visible to MatchWord, and certain function words fail to map to prosodic words when MatchWord is overridden by prosodic subcategorisation frames (Inkelas Reference Inkelas1990, Zec Reference Zec2005). In light of this work, there is reason to rethink the lexical/functional distinction.

In this paper, I argue for a novel formulation of MatchXP, inspired by Truckenbrodt's Lexical Category Condition. I propose that any XP, whether lexical or functional, is visible to MatchXP as long as it has a phonologically overt head. Like the Lexical Category Condition, this definition of MatchXP gives the phonological status of the head a central role in delimiting the set of XPs relevant to the syntax–prosody mapping. Unlike the Lexical Category Condition, this version of MatchXP is indifferent to a head's lexical status, leveraging the fact that being lexical and having phonological content are separate properties. The redefined MatchXP is shown to have desirable consequences in Italian: functional phrases like DP, PP and QP must be matched, while phrases headed by silent elements must not be. The overt head condition makes MatchXP compatible with work arguing against the lexical/functional distinction, while preserving the Lexical Category Condition's insights.

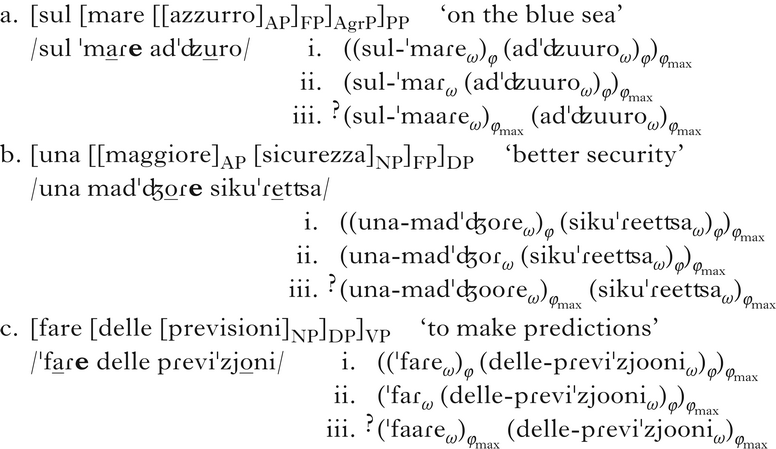

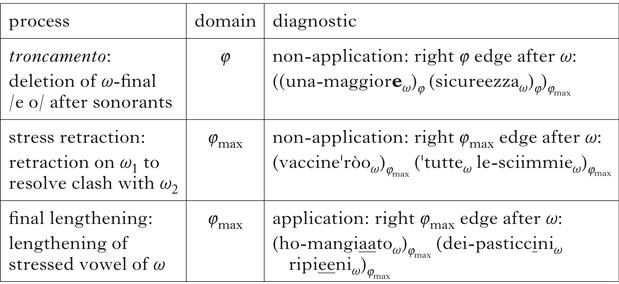

The analysis is based on three Italian phenomena which have been argued to be sensitive to φ: troncamento (Meinschaefer Reference Meinschaefer2005, Reference Meinschaefer2006, Reference Meinschaefer, Kügler, Féry and van de Vijver2009), stress retraction (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986, Ghini Reference Ghini1993) and final lengthening (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986, Ghini Reference Ghini1993). Based on novel data combined with descriptions from previous work, I argue that Italian has two phrasal domains: one diagnosed by troncamento, and the other diagnosed by stress retraction and final lengthening.

Following Match Theory, which argues for a restricted prosodic hierarchy in which the only suprafoot categories are ω, φ and ι, I analyse these two phrasal domains using recursive φ and prosodic subcategories (Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2007, Reference Ito, Mester, Borowsky, Kawahara, Shinya and Sugahara2012, Reference Ito and Mester2013). Prosodic recursion has long been a subject of debate, however. Some researchers contend that recursive structures explain gradient phonetic phenomena and the application of domain-specific rules at the ω level (Booij Reference Booij1996, Peperkamp Reference Peperkamp1997, Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2009, Bennett Reference Bennett2018), the φ level (Ito & Mester Reference Ito, Mester, Borowsky, Kawahara, Shinya and Sugahara2012, Elfner Reference Elfner2015, Elordieta Reference Elordieta2015) and the ι level (Ladd Reference Ladd1986, Féry Reference Féry, Erteschik-Shir and Rochman2010, Myrberg Reference Myrberg2013). However, many theories prohibit prosodic recursion. Early work in prosodic hierarchy theory banned recursion as a result of Strict Layering (Selkirk Reference Selkirk1984, Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986), a stance adopted in much subsequent work (Jackendoff & Pinker Reference Jackendoff and Pinker2005, Vogel Reference Vogel2009, Schiering et al. Reference Schiering, Bickel and Hildebrandt2010). Direct reference theories, which assume that phonological processes are conditioned by morphosyntactic structure without invoking the prosodic hierarchy, typically argue against recursion in phonology (Kaisse Reference Kaisse1985, Seidl Reference Seidl2001, Pak Reference Pak2008, Samuels Reference Samuels2009, Scheer Reference Scheer, Bloch-Trojnar and Bloch-Rozmej2012). This debate is difficult to settle empirically, in part because recursive approaches can often be reanalysed by introducing new categories in the prosodic hierarchy. Similarly, the data in this paper do not uniquely support recursion: a non-recursive account recognising two phrasal domains would be descriptively adequate. With this in mind, the paper addresses several theoretical reasons to pursue recursion, and asks what must hold true of Match Theory to account for Italian, while acknowledging that other frameworks would approach the data differently.

The paper is organised as follows. In §2, I introduce the three φ diagnostics described in previous work: troncamento, final lengthening and stress retraction. In §3, I show that the domain diagnosed by troncamento is distinct from that diagnosed by final lengthening and stress retraction, and that prosodic recursion provides one way of describing these domains. In §4, I propose a formulation of MatchXP that is sensitive only to XPs with phonologically overt heads, and show how the structures proposed in §3 can be derived in Match Theory. In §5, I motivate the novel MatchXP using data from quantifier phrases, ditransitives and Subject + Verb sequences. §6 concludes.

2 Italian φ phenomena

Several processes in Italian have been argued to be diagnostics of the right edge of φ-phrases: (non-application of) word-final vowel deletion (troncamento), (non-application of) stress retraction, and phrase-final vowel lengthening (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986, Ghini Reference Ghini1993, Meinschaefer Reference Meinschaefer2005, Reference Meinschaefer2006, Reference Meinschaefer, Kügler, Féry and van de Vijver2009). In this section, I provide a brief overview of these processes, before presenting evidence in §3 that troncamento is a diagnostic of a different domain than final lengthening and stress retraction.

I assume that all lexical heads, such as nouns, verbs and adjectives, and some function words, such as quantifiers, are mapped to ω, while other function words, like prepositions and determiners, are proclitics (Ghini Reference Ghini1993). I assume that these proclitics form a recursive ω with their host, as in (3) (see Loporcaro Reference Loporcaro and Repetti2000, Bennett Reference Bennett2018; Peperkamp Reference Peperkamp and Kleinhenz1996 has a contrasting view).Footnote 1

-

(3)

2.1 Troncamento

Troncamento is a vowel-deletion process in Standard Italian; previous descriptions are based on troncamento in the Milanese (Nespor Reference Nespor1990) and Florentine (Meinschaefer Reference Meinschaefer2005, Reference Meinschaefer2006, Reference Meinschaefer, Kügler, Féry and van de Vijver2009) varieties of Italian. In troncamento, unstressed word-final mid vowels (/e o/) are deleted after sonorants (/m n l r/) (Nespor Reference Nespor1990, Meinschaefer Reference Meinschaefer2005). This restriction follows from Italian syllable structure, because only sonorants occur in codas (Itô Reference Itô1986). This process is often optional, as in (4). When the adjective migliore is followed by the noun it modifies, its final vowel may either delete (4a) or surface (4b). (All examples are from Meinschaefer Reference Meinschaefer2005, Reference Meinschaefer2006, Reference Meinschaefer, Kügler, Féry and van de Vijver2009, and the potential target of troncamento is in bold in the underlying form.)

-

(4)

Elsewhere, troncamento is prohibited. The same adjective, migliore, fails to undergo troncamento when located at the right edge of a DP, as in (5).Footnote 2

-

(5)

In some constructions, troncamento is obligatory. For instance, it always applies to infinitives followed by a pronominal enclitic (6a) and to modal verbs followed by an infinitive (6b).Footnote 3

-

(6)

Recent accounts argue that troncamento applies obligatorily within φ, and is blocked at φ boundaries (Meinschaefer Reference Meinschaefer2005). This explains why troncamento applies obligatorily in (6a), since clitics phrase with their hosts, but is prohibited in cases like (5), in which the target word is phrase-final and therefore at a prosodic boundary. Under this analysis, non-application of troncamento is a diagnostic of φ boundaries. Optional application indicates the availability of multiple phrasings, as shown by the behaviour of the noun colore in (7). When the target word undergoes deletion, as in (7a), no φ boundary follows the target; when troncamento fails to apply and the vowel surfaces, as in (7b), a φ boundary follows.Footnote 4 (In all examples in this paper, a hyphen between proclitics and their hosts indicates that they belong to the same prosodic word.)

-

(7)

In addition to being sensitive to phrasing, troncamento is lexically restricted. Although the process appears to apply more commonly to verbs, Meinschaefer (Reference Meinschaefer2005) argues that the process treats all lexical categories equally, and that this apparent asymmetry is due to the fact that, while many verbs meet the segmental description for the process, few nouns and adjectives do. I adopt Meinschaefer's view. While troncamento is informally referred to as deletion, it can also be analysed as phonologically conditioned allomorphy, whereby only certain word forms have a truncated alternant; for these forms, the truncated alternant is selected φ-medially (Meinschaefer Reference Meinschaefer, Kügler, Féry and van de Vijver2009). This analysis captures the fact that the process is lexically restricted. For expository purposes, I follow the literature in describing the process as deletion.

2.2 Stress retraction

Stress retraction is another Italian φ process, typically found in northern varieties of the language. This process, also known as the rhythm rule, avoids stress clash between two words, ω1 and ω2, located within the same φ. When ω1 bears final stress and ω2 bears initial stress, the stress on ω1 moves leftward (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986, Ghini Reference Ghini1993). Like troncamento, stress retraction is a diagnostic of φ boundaries: if retraction occurs, then no φ boundary exists after the target word; if retraction fails to apply, then a φ boundary separates the two potential stress-clashing words. All examples of the process are from Nespor & Vogel (Reference Nespor and Vogel1986) and Ghini (Reference Ghini1993). In examples demonstrating (non-)application of retraction, stress is marked using the IPA symbol even in orthographic representations, to aid identification of potential clashes.

This process is illustrated in (8a), in which the clash between the words pescheˈrà and ˈgranchi is resolved by moving stress leftward to the first syllable of ˈpescherà, indicating that these two words belong to the same φ. In contrast, stress remains on the final syllable of pescheˈrà in (8b), despite the potential clash between this word and the following word ˈqualche. The non-application of stress retraction indicates that the two words belong to separate φ's.

-

(8)

2.3 Final lengthening

The third φ phenomenon is final lengthening (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986, Ghini Reference Ghini1993). This process lengthens the stressed vowel of a φ-final word (typically the penultimate vowel), and, like the previous phenomena, has been argued to be a diagnostic of φ boundaries. A boundary occurs after all lengthened words, but no boundary occurs after words that fail to undergo lengthening, as in (9). In (9a), the stressed vowels of mangiato and ripieni are longer than in (b), indicating that they are φ-final in the former but not in the latter. The same holds for pasticcini in (b). All examples are from Nespor & Vogel (Reference Nespor and Vogel1986) and Ghini (Reference Ghini1993). Potential targets of lengthening are underlined in the underlying forms, and lengthening is indicated by doubling of the vowel.

-

(9)

3 The proposal: recursive φ

Previous accounts have identified φ as the domain diagnosed by all three processes. If this hypothesis were correct, then we would expect all three processes to support the existence of boundaries in the same environments. I present novel data showing that this is not the case: a word can fail to undergo troncamento, indicating a boundary, without undergoing lengthening, indicating the absence of a boundary. This suggests that non-application of troncamento is a diagnostic of a different domain than lengthening. This conclusion is supported by the description of optional rule application in previous work: in the configuration [X [Y]YP]XP, the domain diagnosed by troncamento tends to contain a single prosodic word, while the domain diagnosed by retraction and lengthening tends to contain multiple prosodic words. This divergence requires a new analysis, in which troncamento is sensitive to a different domain. I propose that these two domains are different levels of recursive φ: φ and maximal φ (φmax).

The proposal adopts Ito & Mester's (Reference Ito, Mester, Borowsky, Kawahara, Shinya and Sugahara2012, Reference Ito and Mester2013) prosodic subcategory theory. Under this approach, prosodic constituents can be recursive: a φ may dominate another φ, as in (10), and these φ's are organised into subcategories based on their dominance relations. The top φ in (10) is not dominated by any other φ, and is considered a maximal φ, while the φ at the bottom does not dominate any other φ, and is considered a minimal φ (φmin). The intermediate φ is non-maximal and non-minimal, because it both dominates and is dominated by other φ's.

-

(10)

The theory allows phonological processes to refer to subcategories of φ as their domain of application. I propose that troncamento is blocked by any φ: non-application of troncamento is a diagnostic of the right edge of a φ, and this φ may or may not be dominated by additional φ's. In contrast, non-application of stress retraction and application of final lengthening are diagnostics of the right edge of a φmax. This proposal is summarised in Table I.

Table I Boundary diagnostics.

In the following section, I compare the distribution of these processes, in order to motivate the existence of two domains. In line with the recursive analysis, boundaries diagnosed by application of final lengthening and non-application of stress retraction are labelled φmax, while those diagnosed by non-application of troncamento are labelled φ.

3.1 Divergent diagnostics: evidence for different domains

Previous work on troncamento has not investigated the application of troncamento and final lengthening within the same examples. However, the claim that both non-application of troncamento and application of final lengthening are diagnostics of the same domain, φ, makes a testable prediction: any word that fails to undergo troncamento must always undergo lengthening, because lack of troncamento would indicate a φ boundary, and lengthening would apply at a φ boundary. Consider the N + PP sequence in (11). According to the single domain hypothesis, non-application of troncamento in the noun bicchiere would mean that bicchiere is at a right φ edge, and lengthening would obligatorily apply, due to the φ-final position of bicchiere. Stated differently, the single domain hypothesis predicts that lengthening is obligatory in the non-truncated form of words with a truncated alternant.

-

(11)

This prediction is not borne out. Two native speakers of Italian from Milan report that three realisations are possible: in (11a), troncamento fails to apply to bicchiere, while lengthening only applies to vino, in (b), troncamento applies to bicchiere, and lengthening applies only to vino, and in (11c), troncamento fails to apply to bicchiere, while lengthening applies to both bicchiere and vino. Moreover, consultants indicated that the form in (11a) was the most natural, while (c), in which the non-truncated form undergoes lengthening, would be somewhat unusual, and reserved for a slow speech rate. The existence of (11a) poses problems for the single domain hypothesis, which predicts that lengthening should always apply to non-truncated forms, as in (c). The fact that lengthening does not obligatorily occur when troncamento is blocked suggests that the diagnostics are sensitive to different domains. Indeed, these structures can be accounted for under a recursive φ analysis, according to which troncamento is blocked by φ boundaries and lengthening applies at maximal φ boundaries. In (11a), bicchiere fails to undergo troncamento, because it is φ-final, but lengthening does not apply, because bicchiere is not at the edge of a φmax. In (b), there is no right φ edge (maximal or otherwise) following bicchiere, so troncamento applies and final lengthening does not. In (c), bicchiere is φmax-final, so troncamento is blocked and lengthening applies.

This pattern generalises beyond N + PP sequences: the same tripartite distinction is found in sequences of N + A (12a), A + N (12b) and V + DP (12c). The (a) forms, in which the non-truncated word does not undergo lengthening, are problematic for the single domain hypothesis, which predicts that only (b) and (c) should be possible. Clearly, non-application of troncamento does not entail application of final lengthening. The divergence of these diagnostics across various structures supports the existence of separate domains.

-

(12)

Additional evidence against the single domain hypothesis comes from the description of optional application of the three processes in the configuration [X [Y]YP]XP, in which X and Y are two prosodic words that optionally phrase together. Meinschaefer's (Reference Meinschaefer2006, Reference Meinschaefer, Kügler, Féry and van de Vijver2009) corpus data suggest that the domain diagnosed by non-application of troncamento usually consists of a single prosodic word, with X and Y phrasing separately: (Xω)φ(Yω)φ. In contrast, Ghini (Reference Ghini1993) claims that the domain diagnosed by non-application of stress retraction and application of final lengthening tends to contain two prosodic words: (Xω Yω)φ. This divergence shows that the optionality of the processes is not comparable, supporting the claim that there are two different prosodic domains.

The clearest case of a difference between troncamento and the other processes comes from verb + complement sequences (V + Comp). In a corpus study of the Florentine dialect, Meinschaefer (Reference Meinschaefer2006, Reference Meinschaefer, Kügler, Féry and van de Vijver2009) reported the rate of application of troncamento for infinitive verbs followed by a DP direct object or VP-internal PP. The sample was restricted to cases like (13), in which the target verb is followed by a single lexical word, e.g. [X [Y]YP]XP.

-

(13)

This is exactly the environment in which troncamento is reported to be optional, so the rate of application in this configuration reveals whether the domain diagnosed by non-application of troncamento tends to include two words (Xω Yω)φ, i.e. no boundary follows X and deletion takes place, or just one word (Xω)φ(Yω)φ, i.e. a boundary follows X and blocks deletion. Meinschaefer found that deletion, which involves the (Xω Yω)φ structure, only occurs in 35 of 317 tokens (11%). She concludes that troncamento is relatively infrequent in this configuration. I interpret this finding as evidence that the (Xω)φ(Yω)φ phrasing, in which each word is parsed into its own phrase and troncamento is blocked, is more common.

Meinschaefer limited the corpus investigation to those words that undergo troncamento, meaning that the low rate of application cannot be ascribed to the fact that troncamento is lexically restricted. Instead, the rate reflects the fact that words with a truncated alternant typically surface in their full form. Thus troncamento is infrequent in this environment, even among words that can undergo the process.

In contrast, Ghini (Reference Ghini1993) shows that V + Comp tend to phrase together in the domain diagnosed by stress retraction and final lengthening. Consider (14), in which a verb is followed by an unaccusative subject, a syntactic complement. Ghini notes that stress retraction applies ‘without exception’. Further, he states that the phrasing in (14b), in which retraction fails to occur, is marked relative to the phrasing in (a). The domain diagnosed by non-application of stress retraction therefore shows the opposite tendency of the domain diagnosed by non-application of troncamento: here, the (Xω Yω)φ phrasing is more common.

-

(14)

These examples present a paradox under the single domain hypothesis, which states that non-application of troncamento and non-application of stress retraction are diagnostics of the same domain. If non-application of troncamento is our diagnostic, we expect (Xω)φ(Yω)φ to be the more common phrasing of [X [Y]YP]XP. If we use stress retraction as our diagnostic, we reach the opposite conclusion: (Xω Yω)φ is more common. This poses challenges for an account that holds all processes to be diagnostic of one and the same kind of φ.

This paradox generalises beyond the V + Comp cases. In Ghini's (Reference Ghini1993) study of stress retraction and lengthening, he reports that the domain diagnosed by these processes tends to include two prosodic words whenever possible. Ghini claims that ‘broader, i.e. ‘average weight’, phonological phrases’, which are φ's that contain two prosodic words, are ‘much more common’ than φ's that contain a single prosodic word (Reference Ghini1993: 77). Elsewhere, he describes Italian as having ‘a strong tendency to avoid … phonological phrases formed by a single phonological word’ (Reference Ghini1993: 52).

Although phrasings in which each φ contains a single word are possible, they are ‘highly marked’ and require a slow speech rate or ‘discourse factors such as focus’ (Reference Ghini1993: 57). Ghini concludes that ‘restructured moderato φ's’, containing two ω's, are ‘the default phrasing’, while phrasings with ‘adagio ‘non-restructured’’ φ, which contain one ω, ‘are by far more marked’ (Reference Ghini1993: 59). Thus the diagnostics show that [X [Y]YP]XP most often maps to (Xω Yω)φ.

As summarised in Table II, these facts would present a paradox if all three processes were sensitive to the same prosodic boundary: stress retraction and lengthening lead us to believe that (Xω Yω)φ is the more common phrasing for [X [Y]YP]XP, while troncamento leads us to believe that (Xω)φ(Yω)φ is more common. The single domain analysis cannot handle this paradox, because diagnostics for the same domain should converge on the same conclusions.

Table II Divergent diagnostics for [X [Y]YP]XP.

This paradox disappears under a recursive analysis in which troncamento is sensitive to φ while stress retraction and lengthening are sensitive to φmax. Under this analysis, the structure [X [Y]YP]XP can map onto the three prosodic parses in Table III; note that parses (a)–(c) are parallel to the parses in (11) and (12). In parse (a), both words constitute separate φ's, but are phrased together in a single φmax. Troncamento on X is blocked, due to the following φ boundary, but stress retraction applies and lengthening fails to apply to X, due to the lack of an immediately following φmax boundary. This represents the most common phrasing: the domain diagnosed by non-application of troncamento, φ, contains one ω, while the domain diagnosed by retraction and lengthening, φmax, contains two. Parse (b) does not place X into its own φ; troncamento applies due to the lack of a right φ boundary. This phrasing is less common, since troncamento is relatively infrequent in this environment. Finally, parse (c) places each word in a separate φmax. In this case, stress retraction is blocked, and lengthening applies in X due to the φmax boundary; troncamento is also blocked, because φmax is a φ. This represents the exceptional case, where the domain diagnosed by retraction and lengthening consists of a single prosodic word at a slow rate or under focus. Together, these three phrasings allow for ‘optional’ application of all three processes, while capturing the tendency for the domain diagnosed by troncamento to contain one ω.

Table III Prosodic parses of [X [Y]YP]XP.

Finally, this analysis accounts for the generalisation that non-application of stress retraction and application of final lengthening are diagnostics of the same domain (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986, Ghini Reference Ghini1993). As shown in (15a), these diagnostics converge: lengthening applies to the verb vaccineˈrò, and stress retraction fails to apply, both of which indicate a boundary. In contrast, in (15b), lengthening fails to apply and retraction occurs, diagnosing the absence of a boundary.

-

(15)

To summarise, I have provided new data showing that non-application of troncamento does not entail application of final lengthening, contra the predictions of the hypothesis that these diagnostics are sensitive to the same domain. I have also identified an apparent paradox for any account positing only one level of φ, to which all three processes should be sensitive: using non-application of troncamento as a φ diagnostic suggests that the phrasing (Xω)φ(Yω)φ is more common than (Xω Yω)φ in the configuration [X [Y]YP]XP, while non-application of stress retraction and application of final lengthening suggest the opposite. These findings render the position that all three processes diagnose the same domain untenable. To resolve this potential paradox, I have appealed to recursive φ: troncamento is sensitive to all φ boundaries, while stress retraction and final lengthening are sensitive to φmax boundaries. In the next section, I sketch an alternative account, which captures the data by introducing a new category into the prosodic hierarchy.

3.2 Alternatives to recursion

Non-recursive approaches recognise that troncamento is sensitive to a smaller domain than stress retraction and final lengthening, but explain this divergence by appealing to separate categories on the prosodic hierarchy. One possibility is to assert that troncamento is sensitive to φ boundaries, while stress retraction and final lengthening are sensitive to ι boundaries, the next category on the prosodic hierarchy. However, stress retraction and lengthening cannot be ι diagnostics, because their distribution differs from that of gorgia toscana, a spirantisation process that is blocked at ι boundaries (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986). As shown in (16a), gorgia toscana applies between a subject and a verb: initial /k/ in the verb costruiscono surfaces as [h], diagnosing the absence of an ι boundary after the subject. If ι were also the domain of stress retraction and final lengthening, then retraction would apply between a subject and a verb, and lengthening would not occur in a preverbal subject, because there would be no ι boundary after the subject. In fact, the opposite is true: in (16b), the subject Paˈpà undergoes lengthening and does not undergo retraction, despite a potential clash (Ghini Reference Ghini1993). Application of lengthening and non-application of retraction are diagnostics of the presence of a post-subject boundary; this divergence from gorgia toscana indicates that retraction and lengthening are not ι diagnostics. Moreover, the previous examples show that these two processes are sensitive to clause-internal boundaries, which would be unexpected if they were ι diagnostics.

-

(16)

Another approach would avoid recursion by positing a new category in the prosodic hierarchy. This analysis would index stress retraction and final lengthening to φ and troncamento to a new category – call it π. These two approaches are schematised in (17).

-

(17)

The non-recursive alternative would be empirically adequate: the Italian data in the preceding section require two phrasal domains, but these domains need not be of the same category. However, I argue that there are theoretical reasons to prefer recursion. First, it is unclear what the domain π should be. One contender is the clitic group, which consists of ω and any dependent clitics (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986). Indeed, it has been argued that troncamento applies obligatorily within the clitic group (Nespor Reference Nespor1990). However, subsequent work has challenged the clitic group's existence (Zec & Inkelas Reference Zec and Inkelas1991, Booij Reference Booij1996, Peperkamp Reference Peperkamp and Kleinhenz1996). Zec & Inkelas (Reference Zec and Inkelas1991) provide cross-linguistic data showing that clitics attach not only to ω, but also to φ and ι, and Peperkamp (Reference Peperkamp and Kleinhenz1996) uses variation in Italian dialects to argue that clitics can be prosodified in various ways: by adjunction to ω, incorporation into ω or attachment to φ. These authors contend that the non-uniform behaviour of clitics is evidence against the clitic group as a distinct constituent between ω and φ. Peperkamp also shows that analyses invoking the clitic group can be reanalysed without reference to this constituent. Finally, in the majority of the examples considered thus far, troncamento occurs between two independent ω's, which constitute a domain larger than the clitic group, and the process is sensitive to XP boundaries. As argued by Meinschaefer (Reference Meinschaefer2005, Reference Meinschaefer2006), these facts suggest that troncamento is sensitive to a phrasal domain. Thus, identifying π with the clitic group is problematical.

One could still introduce a category π, provided that this category is larger than a clitic and its host. This analysis runs into a problem noted frequently in the literature: positing new domains leads to a proliferation of categories, without any principled limit on the number of categories we expect to find and no explanation of where they come from (Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2007, Reference Ito, Mester, Borowsky, Kawahara, Shinya and Sugahara2012, Reference Ito and Mester2013, Selkirk Reference Selkirk2009, among others). Ito & Mester (Reference Ito, Mester, Borowsky, Kawahara, Shinya and Sugahara2012, Reference Ito and Mester2013) provide an overview of this problem in Japanese, in which two phrasal domains have traditionally been recognised: the major phrase and the minor phrase. Ito & Mester point out that using multiple categories is problematic for the hypothesis that there is a straightforward correspondence between syntactic and prosodic constituents: while the major phrase corresponds to XPs, the minor phrase is defined in phonological terms, and lacks a clear syntactic correspondent. Abandoning the requirement that all suprafoot categories have a syntactic correspondent opens the door to more categories, with no clear limit on the number of categories. Indeed, Shinya et al. (Reference Shinya, Selkirk, Kawahara, Bel and Marlien2004) introduce a third level for Japanese, the superordinate minor phrase. This proliferation of categories makes cross-linguistic comparison difficult, because categories are often proposed on a language-specific basis. Ito & Mester argue that an analysis employing recursive φ can account for the data with a single category, while avoiding these issues.

Similar problems arise with π in Italian: it is unclear whether there are limits on the number of categories and whether the same categories should exist in other languages. Adding a domain also fails to explain why both π and φ are sensitive to XP boundaries; this fact remains a mere coincidence. In contrast, recursion provides an explanation: recursive φ are built on nested XPs. While particular levels of φ may exhibit unique properties, they are constructed on the same kind of syntactic object, so it is unsurprising that different levels coincide with XP boundaries. Moreover, the suprafoot prosodic hierarchy is restricted to the syntactically grounded categories ι, φ and ω: there is a principled limit on the number of categories, with a straightforward explanation of where they come from.

These arguments are admittedly theoretical, and proponents of other frameworks could counter that the present approach has its own theoretical issues. While recursion avoids category proliferation, the need to reference prosodic subcategories increases the complexity of the constraint set. I have also assumed that a restricted prosodic hierarchy is a desirable component of the theory; however, direct reference theorists eschew the idea of a prosodic hierarchy (Kaisse Reference Kaisse1985, Pak Reference Pak2008, Samuels Reference Samuels2009, Scheer Reference Scheer, Bloch-Trojnar and Bloch-Rozmej2012), and are unlikely to be convinced by these arguments. Still, the arguments are worth reviewing as a reminder of what is at stake in the debate over recursion, and to motivate the use of Match Theory in this paper. The recursive treatment of Italian should be taken as a proof of concept, rather than the only way to approach these data, and alternative analyses would likely be descriptively adequate.

To summarise, a recursive analysis accounts for the fact that troncamento is diagnostic of a different domain than final lengthening and stress retraction. In the rest of the paper, I analyse Italian in Match Theory. Italian has previously been analysed in edge-based theories using Align and Wrap constraints (Samek-Lodovici Reference Samek-Lodovici2005, Truckenbrodt Reference Truckenbrodt and de Lacy2007, Dehé & Samek-Lodovici Reference Dehé and Samek-Lodovici2009). These accounts have assumed that Italian lacks φ-recursion, but the framework is compatible with recursion, and could potentially account for the data presented here. Here, I pursue an account in Match Theory, which predicts the existence of prosodic recursion due to the tight correspondence between XPs and φ. I argue for a novel version of MatchXP, according to which only XPs with phonologically overt heads are mapped to φ.

4 Italian φ-phrasing in Match Theory

In this section, I analyse Italian in Match Theory. I begin by reviewing the basic assumptions of Match Theory and by introducing a standardly assumed set of Match and markedness constraints. I then motivate a constraint ranking for Italian, showing that this framework straightforwardly derives the recursive structures proposed in §3.

4.1 Match constraints and syntactic preliminaries

Match Theory advocates a direct correspondence between syntactic and prosodic elements: syntactic words, X0, are mapped onto prosodic words, ω, syntactic phrases, XP, are mapped onto phonological phrases, φ, and syntactic clauses are mapped onto intonational phrases, ι. This mapping is enforced through a family of Match constraints. One class of Match constraints, the syntax-to-prosody constraints, requires that a syntactic constituent α in the syntactic representation stand in a correspondence relationship (McCarthy & Prince Reference McCarthy, Prince, Beckman, Dickey and Urbanczyk1995) with a prosodic constituent π in the phonological representation (Selkirk Reference Selkirk, Goldsmith, Riggle and Yu2011); corresponding constituents must also dominate the same terminal nodes, as will be explained shortly (Elfner Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015). At the phrasal level, MatchXP, defined in (18a), penalises a structure in which an XP in the syntax is not matched by a corresponding φ in the prosodic representation. Another class, the prosody-to-syntax constraints, penalises structures in which a prosodic constituent π has no correspondent α in the syntax. For phrases, Matchφ, defined in (18b), assigns violations to structures containing φ that are not motivated by the syntax. In a departure from previous work, I propose that only XPs with phonologically overt heads are visible to MatchXP and Matchφ; this formulation will be developed below.

-

(18)

As discussed in §1, there is an ongoing debate over whether Match constraints distinguish lexical and functional elements. Selkirk & Lee's (Reference Selkirk and Lee2017) MatchPhraseLex incorporates Truckenbrodt's (Reference Truckenbrodt1999) Lexical Category Condition, and only sees XPs with phonologically overt lexical heads. However, Elfner (Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015) and Tyler (Reference Tyler2019) argue that functional phrases like ΣP, TP and coordinated phrases are visible to MatchXP, suggesting that the lexical/functional distinction is too strong, at least in some languages. At the word level, Tyler argues that the lexical/functional distinction should be abandoned, because function words have idiosyncratic behaviour and do not constitute a uniform class; for instance, he argues that the demonstrative determiner that and the preposition via are prosodic words, despite being functional. This work casts doubt on the strongest version of the lexical/functional distinction.

The proposed formulation of MatchXPOH preserves the second part of the Lexical Category Condition, which requires XPs to have a phonologically overt head, while abandoning the lexical requirement. This definition attempts to reconcile two ideas: (i) not all XPs are mapped to φ's, and our theory should predict which XPs will be matched, and (ii) the lexical/functional distinction is a potentially problematic way to delimit this set of XPs, because it is too aggressive in ruling out all functional XPs. I assume that all syntactic terminals with phonological content, including functional heads that are clitics, are considered overt, and their maximal projection is therefore visible to MatchXPOH. Only syntactic terminals that have no phonological content, or that have undergone movement leaving behind a trace, are considered silent. This has important consequences for structures in which movement has taken place. In (19), the head of YP, y, has raised to W. According to Elfner's (Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015) MatchXP, which matches any XP dominating a unique set of terminal nodes, YP should be matched, because it dominates the unique set {x, z}. However, MatchXPOH will ignore YP, because its head is a trace, which is silent. Note that the same result would obtain under the copy theory of movement (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995), provided that lower copies are deleted before the syntactic structure is made available to the phonology. Under this view, the head of YP would be the deleted (and therefore silent) copy, and YP would be invisible to MatchXPOH. At present, I assume the newly proposed MatchXPOH, and I will explicitly argue in favour of this formulation in §5.

-

(19)

A reviewer notes a possible issue: MatchXPOH requires the phonology to distinguish overtly headed phrases from those with silent heads. This might imply that syntactic labels are available to phonology, so that the phonology ‘knows’ whether, for example, a VP contains an overt head V. This is potentially problematic under the common assumption that syntactic labels are unavailable to phonology. One possibility, suggested by the reviewer, is that syntactic labels are replaced by arbitrary, syntactically neutral labels (e.g. A, B, C). For instance, VP and V could be replaced by the labels BP and B, allowing the phonology to check whether a phrase BP contains an overt head B without giving it access to syntactic labels. Under this view, (19) would be an example of the input to phonology: phrase structure is provided, labels are arbitrary and lower copies have been deleted. Other solutions are possible, including relaxing the assumption that syntactic labels are never available to phonology. The exact mechanism by which overtly headed XPs are identified is incidental to my main point: this is the set of XPs that must be matched.

Another question concerns what it means for an XP to ‘match’ a φ. I adopt Elfner's (Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015) definition, which states that a φ matches an XP if the φ dominates all and only the phonological exponents of the terminal nodes of XP. This is demonstrated in (20). The syntactic structure in (20a) contains three phrases; each phrase dominates a unique set of terminal nodes: XP dominates {x, y, z}, YP dominates {y, z} and ZP dominates {z}. The structure in (20b) is perfectly matched: each φ dominates the same terminal nodes as its syntactic correspondent. In contrast, (20c) violates MatchXP, because YP and ZP lack φ correspondents. Although φXP dominates all of the terminal nodes dominated by YP and ZP, this does not count as matching, because φXP does not contain only those terminal nodes dominated by YP and ZP. Note that MatchXP is not equivalent to WrapXP, which requires each XP to be contained in a φ (Truckenbrodt Reference Truckenbrodt1999). WrapXP would be satisfied by (20c), because the terminal nodes dominated by YP and ZP are contained in φXP.

-

(20)

Following much work in Match Theory (Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2013, Reference Ito and Mester2019, Elfner Reference Elfner2015, Selkirk & Lee Reference Selkirk and Lee2015, Cheng & Downing Reference Cheng and Downing2016), I assume that the syntax is available to phonology only after the entire derivation is complete. This differs from phase-based spell-out approaches, in which prosody is built cyclically throughout the derivation (Dobashi Reference Dobashi2003, Wagner Reference Wagner2005, Ishihara Reference Ishihara2007, Kratzer & Selkirk Reference Kratzer and Selkirk2007, Newell & Piggott Reference Newell and Piggott2014). However, Match Theory and phase-based spell-out are not incompatible, and some analyses adopt both (Selkirk Reference Selkirk2009, Elfner Reference Elfner2012).

I also adopt bare phrase structure (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995), which raises an interesting issue when a syntactic element is both maximal and minimal, such as an NP consisting of a single word, as in (21a) (Elfner Reference Elfner2015, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Elfner and McCloskey2016). As a minimal projection, the noun libri should be mapped to ω by MatchWord. Yet, as a maximal projection, the NP libri should be mapped to φ by MatchXP. I assume that elements like libri are visible to both MatchWord and MatchXP and that the preferred configuration is (21b), with both ω and φ.

-

(21)

With these assumptions in place, let us consider how MatchXPOH would parse an Italian SVO sentence, for which I assume the clause structure in (22).

-

(22)

This clause structure is relatively minimal. Following previous work on Italian syntax, one could adopt a more articulated structure, by decomposing CP and TP into a series of functional projections such as ForceP, TopP and AgrP (e.g. Pollock Reference Pollock1989, Belletti Reference Belletti1990, Reference Belletti, Lightfoot and Hornstein1994, Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997, Cinque Reference Cinque1999). Most of these projections have silent heads, which will render them invisible to MatchXPOH, and irrelevant for the syntax-to-prosody mapping. I omit these projections from the syntactic representations for expository purposes, while noting that a more articulated structure is compatible with the analysis.

Second, I assume that the verb raises to T (Belletti Reference Belletti1990, Reference Belletti, Lightfoot and Hornstein1994, Cardinaletti Reference Cardinaletti and Haegeman1997, Samek-Lodovici Reference Samek-Lodovici2005, Dehé & Samek-Lodovici Reference Dehé and Samek-Lodovici2009). This is supported by the appearance of the finite verb to the left of floated quantifiers and various adverbs (Belletti Reference Belletti1990, Reference Belletti, Lightfoot and Hornstein1994).

Third, I assume that the subject raises to the specifier of a functional projection above TP (Cardinaletti Reference Cardinaletti and Haegeman1997, Reference Cardinaletti and Rizzi2004, Poletto Reference Poletto2000, Rizzi Reference Rizzi, Brugè, Giusti, Munaro, Schweikert and Turano2005, Frascarelli Reference Frascarelli2007, Dehé & Samek-Lodovici Reference Dehé and Samek-Lodovici2009). As observed by Dehé & Samek-Lodovici, previous analyses agree that the subject is in a higher functional projection than the verb; these analyses diverge primarily in whether the subject is in the inflectional domain (Cardinaletti Reference Cardinaletti and Haegeman1997, Reference Cardinaletti and Rizzi2004, Rizzi Reference Rizzi, Brugè, Giusti, Munaro, Schweikert and Turano2005) or the C-domain (Poletto Reference Poletto2000, Frascarelli Reference Frascarelli2007). This subject position is motivated by the finding that the subject and the verb can be separated by parentheticals, sentential adverbs and subordinate clauses; the reader is referred to the cited works for additional arguments. Because the precise location is unimportant for present purposes, I label this projection FP; candidates include Cardinaletti's (Reference Cardinaletti and Rizzi2004) SubjP and Frascarelli's (Reference Frascarelli2007) ShiftP. The important point is that the subject is outside of TP, which will be crucial in explaining why the subject and verb phrase separately in §5.2.2.

For the SVO syntactic input in (22), MatchXPOH will prefer the prosodic output in (23). Assuming that the subject and object are DPs with overt heads, they will each be mapped to a φ, as will any overtly headed XPs within these DPs. TP is mapped to a φ because the verb has raised to T, making the head of TP overt. FP, vP and VP are invisible to MatchXPOH: FP has a silent head, while vP and VP are headed by a trace (or deleted copy), and MatchXPOH does not build any φ's corresponding to these XPs. Since FP is phonologically invisible, there is no φ containing S, V and O. The invisibility of vP and VP prevents vacuous recursion: vP and VP each dominate only O, and, by ignoring these XPs, MatchXPOH avoids having three φ's dominate O, e.g. (((O)φ)φ)φ. Note that MatchClause maps CP to ι (Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2013, Ishihara Reference Ishihara2014, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Elfner and McCloskey2016). A question that cannot be answered here is whether an overtly headed CP is visible to both MatchClause and MatchXP. We might expect CP to be visible to MatchXP when it has an overt head, because CPs are maximal projections, but it may be the case that CPs are only visible to MatchClause. I set this question aside, and refer the reader to Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Elfner and McCloskey2016) for further discussion.

-

(23)

4.2 Prosodic markedness constraints

While the structure in (23) illustrates the syntax–prosody mapping favoured by MatchXPOH, higher-ranked prosodic markedness constraints lead to syntax–prosody non-isomorphism. First, there is a cross-linguistic preference for prosodic constituents to be binary (e.g. Ghini Reference Ghini1993, Selkirk Reference Selkirk and Horne2000, Reference Selkirk, Goldsmith, Riggle and Yu2011, Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2007). Binarity constraints capture this tendency, but there are different ways to evaluate binarity. Adopting the terminology of Bellik & Kalivoda (Reference Bellik, Kalivoda, Hansson, Farris-Trimble, McMullin and Pulleyblank2016), branch-counting binarity requires a prosodic constituent to have two daughters of any category, while leaf-counting binarity requires a constituent to dominate two nodes of a particular category, even if these nodes are not immediately dominated. In (24a), φ1 is binary branching because it has two daughters, ω1 and φ2. However, φ1 is ternary when counting leaves, because it dominates three ω's: ω1, ω2 and ω3. Similarly, (24b) is binary branching, but is unary according to leaf-counting, because it only dominates one ω. Leaf-counting binarity is adopted here in order to penalise structures like (24a), which will be necessary in §4.3. (See Selkirk Reference Selkirk, Goldsmith, Riggle and Yu2011, Ito & Mester Reference Ito and Mester2013 and Ishihara Reference Ishihara2014 for additional analyses employing leaf-counting.)

-

(24)

Another issue arises when evaluating leaf-counting binarity in recursive structures. In (25a), φ is unambiguously binary: φ has two daughters, both of which are ω. The structure in (25b), in which a syllable has procliticised onto ω3, creating a recursive ω, is less straightforward. Should ω2 and ω3 count once towards binarity, since they are segments of the same complex word, or twice, because there are two ω nodes?

-

(25)

Intuitively, leaf-counting constraints evaluate the number of independent words, and creating a recursive ω with a clitic is not equivalent to having two separate prosodic words. Moreover, Ghini (Reference Ghini1993) shows that, in Italian, a ω without clitics behaves in the same way as one containing clitics: both count as one ω. For this reason, leaf-counting must be defined such that the recursive ω in (25) is counted once, such that the φ is considered binary. This can be accomplished by counting the number of maximal ω's dominated by φ. This ensures that only independent ω's, e.g. ω1 and ω2, but not layers of a single recursive ω, e.g. ω3, count toward binarity. The constraints Binmin(φ) and Binmax(φ) are defined in (26a) and (26b). The former penalises a φ that does not contain at least two ω's, while the latter penalises one that contains more than two ω's. Binmax(ι), which penalises an ι dominating more than two φ's, will also be relevant, and is defined in (26c).

-

(26)

Another constraint, StrongStart, militates against weak elements at the beginning of prosodic constituents (Selkirk Reference Selkirk, Goldsmith, Riggle and Yu2011, Elfner Reference Elfner2012, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Elfner and McCloskey2016). As defined in (26d), StrongStart assigns violations to prosodic constituents whose leftmost daughter is lower on the prosodic hierarchy than the sister node to its immediate right (Elfner Reference Elfner2012). This constraint penalises structures like (27a), in which ω is the leftmost daughter of φ, and weaker than its sister φ, but allows structures like (27b), in which both sisters are φ, and (27c), in which the leftmost daughter φ is stronger than its sister ω.

-

(27)

This constraint set can capture many generalisations about Italian. The interplay of Binmin(φ) and StrongStart derives the optionality of troncamento, while Binmax(φ) limits the amount of recursion we find, allowing for departures from the syntax.

4.3 Upper limits on φ size

Various structures show that Italian φ's consist of at most two ω's, resulting in syntax–prosody non-isomorphism.Footnote 5 Consider the minimal pair in (28) (from Ghini Reference Ghini1993). In (28a), the noun entrata is followed by a PP consisting of a single ω, and only the last noun fiera undergoes final lengthening. This suggests that entrata and the PP are in the same φmax. However, in (b), the PP contains two ω's. Here, the first and third nouns, entrata and Milano, undergo lengthening, while fiera does not. This suggests the phrasing in (28b), in which entrata is in its own φmax and the PP phrases separately.Footnote 6

-

(28)

Following Ghini (Reference Ghini1993), I assume that the DP in (28b) is broken up into two φmax's, because Italian φ cannot exceed two ω's; this is enforced by Binmax(φ). As shown in (29), Binmax(φ) rules out candidate (c), which maps the entire DP to a φ. In fact, Binmax(φ) must be undominated, because the perfectly matched candidate (c) fares better than the winner on all other constraints. By respecting Binmax(φ), candidate (a) violates both MatchXPOH, because DP1 is not matched, and MatchφOH, because entrata occupies its own φ, despite not constituting an XP. This is a clear case where markedness constraints force non-isomorphism. Candidate (b) shows that MatchXPOH must be ranked above Binmin(φ): it has one less unary φ than (a), but fails to match DP1 and PP1. Finally, there is no evidence for the relative ranking of MatchφOH and either MatchXPOH or Binmin(φ).

-

(29)

Note that certain XPs will never be matched, due to the assumption that function words procliticise onto their host. For instance, the preposition alla procliticises onto fiera, preventing the creation of a φ corresponding to NP that would exclude alla. This does not mean that NP is invisible to MatchXPOH; rather, MatchXPOH would attempt to match NP by default, but higher-ranking constraints requiring the preposition to procliticise onto the noun prevent NP from being matched, violating MatchXPOH. These violations are omitted from the tableaux, because they are incurred by all candidates. For clarity, the label of every XP that could be matched (i.e. that has an overt head and is not prevented from matching due to proclitics) is in bold in the input. All examples are monoclausal and consist of a single ι; ι brackets are therefore omitted.

4.4 Optional phrasing and variable constraint ranking

Optional application of troncamento was demonstrated in §3.1 for N + A, A + N and V + N sequences, and is illustrated for an N + PP sequence in (30).

-

(30)

Again, I assume that different phrasings lead to optionality: troncamento applies to sapore when no right φ boundary follows, as in (30a), but is blocked when there is a φ boundary, as in (b). The current ranking does not accommodate optionality. In (31), candidate (a), without a boundary after sapore, harmonically bounds (b), in which troncamento is blocked. Candidate (b) loses because the φ il sapore incurs additional violations of MatchφOH and Binmin(φ).

-

(31)

To select candidate (b), we need a constraint that prefers the structure in (32b) to that in (32a). Specifically, il sapore must map to φ, despite lacking an XP correspondent. I propose that this promotion of the ω il sapore to a φ is a consequence of StrongStart, which prefers (32b) because the alternative begins with a ω that is weaker than its φ sister.

-

(32)

To allow both (32a) and (b) as possible outputs, I follow Myrberg (Reference Myrberg2013), who employs variably ranked constraints to capture variation in Swedish phrasing; see also Anttila (Reference Anttila, Hinskens, van Hout and Wetzels1997). When two constraints A and B are variably ranked, the grammar has two different rankings: one in which A is ranked above B, and another in which B is ranked above A. If constraints A and B favour different candidates, each ranking produces a different output. For Italian, StrongStart, MatchφOH and Binmin(φ) are variably ranked (indicated by jagged lines in (33)). When either MatchφOH or Binmin(φ) is ranked above StrongStart, candidate (a) is chosen, and troncamento applies. If StrongStart is ranked above both MatchφOH and Binmin(φ), candidate (b) is chosen, and troncamento is blocked.

-

(33)

This analysis shows how mapping from XPs to φ's derives the nested φ structure argued for in §3, allowing optional troncamento on the first word of a two-word XP without affecting non-application of lengthening on that same noun. High-ranked MatchXPOH ensures that the full DP is mapped to a φmax, such that only the second ω is targeted by lengthening. Meanwhile, the variable ranking of StrongStart, Binmin(φ) and MatchφOH ensures that the noun sapore is not always located at a φ edge, allowing for variability in troncamento.

5 Redefining MatchXP: matching overtly headed XPs

So far, I have assumed that MatchXPOH attempts to match only those XPs with an overt head. In this section, I explicitly argue in favour of MatchXPOH over two alternatives: MatchXPLex, which only matches lexical phrases (Selkirk Reference Selkirk, Goldsmith, Riggle and Yu2011, Selkirk & Lee Reference Selkirk and Lee2017), and general MatchXP, which matches any phrase that dominates a unique terminal string, even if its head is silent (Elfner Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015). I first argue that functional phrases with overt heads must be visible to MatchXPOH; enforcing a lexical/functional distinction incorrectly excludes DPs, PPs and QPs. I then consider ditransitives and Subject + Verb sequences, both of which show that silently headed phrases must be ignored. I conclude that MatchXP must be restricted. MatchXPOH reconciles the claim that not all XPs are relevant to prosody with recent work which argues that the lexical/functional distinction is irrelevant for Match constraints (Elfner Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015, Tyler Reference Tyler2019).

5.1 Matching functional XPs with overt heads

I have shown that the correct phrasings can be derived even when we assume that functional phrases like PP and DP are visible to MatchXPOH. This suggests that the proposed MatchXPOH, which ignores the lexical/functional distinction, is on the right track. However, a reviewer suggests an alternative: that functional XPs like PP and DP are matched because they contain a lexical XP that cannot be matched once the clitics have procliticised onto the lexical head. For instance, one could argue that [D [N]NP]DP is mapped to (D N)φ because the lexical NP needs to be matched, and D has procliticised onto N. This would preserve the lexical/functional distinction, but the approach encounters various issues. Without additional stipulation, this explanation is incompatible with the idea that MatchXP is satisfied when a φ dominates all and only those terminal nodes that are dominated by its correspondent in the syntax: (D N)φ cannot be a match for NP, because NP does not dominate D in the syntax. One could adjust this definition of matching, perhaps by stipulating that proclitics are invisible when evaluating MatchXP. Yet this amounts to saying that DP and D are invisible in order to create a φ containing exactly those terminal nodes dominated by DP: D and N. The stipulation is unnecessary: if we allow DP and D to be visible, the creation of (D N)φ is an unremarkable consequence of MatchXPOH. Avoiding a stipulation that renders functional elements invisible also preserves the insights of work showing that certain functional phrases must be visible to MatchXP (Elfner Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015).

More importantly, this alternative, which appeals to procliticisation, cannot account for cases in which a functional phrase headed by an independent ω must be matched. Consider (34), in which a verb takes a two-word QP as a complement (Ghini Reference Ghini1993). The φ diagnostics show that the verb vaccineˈrò forms a separate phrase: the potential clash between the verb and the quantifier ˈtutte is permitted, and the verb undergoes lengthening.

-

(34)

Under the analysis that a quantifier is the head of a functional projection QP taking a DP complement (Cardinaletti & Giusti Reference Cardinaletti and Giusti1991, Giusti Reference Giusti1991, Bianchi Reference Bianchi1992, Cinque Reference Cinque1992), QP will be visible to MatchXPOH: although QP is functional, its head is overt. The tableau in (35) shows how MatchXPOH derives the correct phrasing. Candidate (b), in which the verb phrases with the quantifier, is ruled out because QP is not matched.

-

(35)

In contrast, QP would be invisible to MatchXPLex, because of its functional status; this would predict the wrong phrasing, as shown in (36). Candidate (b), in which the verb phrases with the quantifier, is not ruled out by MatchXPLex, because failure to match QP does not incur a violation. Even worse, the desired winner, (a), incurs an additional MatchφLex violation, because the φ corresponding to QP is not motivated by the syntax when functional XPs are invisible. The desired winner is harmonically bounded by candidate (b). Thus, making all functional phrases invisible to Match constraints has undesirable consequences. Moreover, the suggestion that functional phrases are matched only when a function word has procliticised into a lexical XP cannot be invoked to preserve the lexical/functional distinction, because the quantifier is not a clitic.

-

(36)

5.2 Ignoring XPs with silent heads

While the lexical/functional distinction is undesirable, this does not mean that every XP is matched. MatchXPOH retains the second part of Truckenbrodt's Lexical Category Condition, which renders XPs with a silent head invisible to the syntax–prosody mapping. Next, I show that this condition is necessary to account for the phrasing of ditransitives and Subject + Verb sequences: for each structure, Elfner's (Reference Elfner2012, Reference Elfner2015) MatchXP, which matches any XP dominating a unique terminal string, makes the wrong predictions. In contrast, MatchXPOH can derive the right structures, provided that we also revise the definition of StrongStart.

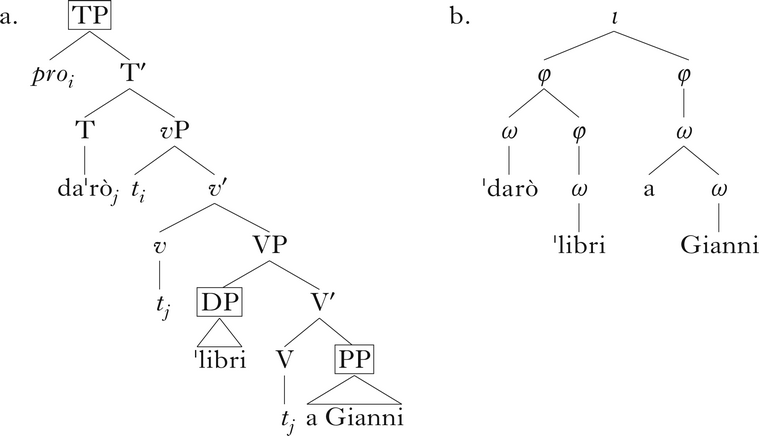

5.2.1 The ditransitive mismatch

Consider the ditransitive sentence in (37) (from Ghini Reference Ghini1993). Ghini reports that the verb daˈrò and the direct object ˈlibri phrase together to the exclusion of the indirect object a Gianni, as in (37a); the alternative phrasing in (b) is ungrammatical. Ghini's phrasing is supported by stress retraction: retraction occurs to avoid a potential clash between the verb daˈrò and the direct object ˈlibri, showing that they are in a single φmax.Footnote 7

-

(37)

Ditransitives constitute a syntax-to-prosody mismatch. In the analysis of ditransitives in (38a) (Larson Reference Larson1988, Belletti Reference Belletti1999), the verb darò raises out of VP, leaving DP and PP behind. If VP were matched, we would expect a φ containing only DP and PP. Instead, DP and PP phrase separately. MatchXPOH helps us understand why DP and PP are not phrased together (boxes are placed around XPs with overt heads). MatchXPOH ignores the silently headed VP, eliminating the pressure to construct a φ containing only DP and PP. This analysis has precedent: MatchXPOH is inspired by the second part of Truckenbrodt's (Reference Truckenbrodt1999) Lexical Category Condition, which proposes that projections with silent heads are ignored in order to render an empty-headed VP invisible in Chicheŵa.

-

(38)

While ignoring XPs with silent heads is necessary to avoid phrasing DP with PP, MatchXPOH by itself is insufficient to derive (38b). This is because ditransitives also constitute a prosody-to-syntax mismatch: the verb phrases with DP in the prosody, as in (38b), but no corresponding XP exists in the syntax. MatchXPOH cannot force the verb to phrase with DP, and (39) shows how the current grammar selects several winners: candidates (a) and (b) correctly phrase the verb with the direct object, while (c) incorrectly phrases the verb by itself. Due to the variable ranking of StrongStart, MatchφOH and Binmin(φ) established in §4.4, we cannot rule out (c) with the current constraints. The desired winner, (a), performs better than the problematic (c) on MatchφOH and Binmin(φ), yet fares worse on StrongStart. Thus, whenever StrongStart is ranked above these two constraints, (c) will win over (a). Moreover, (b), which also phrases the verb with DP, incurs the same violations as (c), so we have no way to choose (b) over (c). Note that Binmax(ι) eliminates (d), in which each word is parsed into its own φmax, creating a ternary ι. Binmax(ι) is above the three variably ranked constraints, but we cannot establish where Binmax(ι) ranks with respect to Binmax(φ) and MatchXPOH.

-

(39)

How do we eliminate candidate (c), to ensure that only candidates that phrase the verb with DP win? Compare the representations of candidates (b) and (c) in (40), which differ in constituent order: in the preferred winner, (b), a non-minimal φ precedes a minimal φ, while the reverse is true in (c). Since (b) must win over (c), this suggests that there is something marked about a minimal φ preceding a non-minimal φ. Intuitively, we might expect a minimal φ to be prosodically weaker than a non-minimal φ, since the latter contains additional φ structure by definition.

-

(40)

Under this interpretation, the preference for (b) over (c) can be considered a StrongStart effect. However, StrongStart applies only to differences in category level, such as ω vs. φ, not to subcategories. I therefore redefine StrongStart in (41). This new constraint evaluates the relative strength of constituents of the same category and penalises structures like (c), in which the leftmost φ is minimal, and weaker than the non-minimal φ to its right. Note that this constraint is concerned with differences in minimal/non-minimal status: the maximal/non-maximal status of sister nodes is irrelevant. In fact, it is impossible for sister nodes to differ in their maximal status, because sister nodes have the same mother by definition, e.g. a non-maximal φ has a φ mother, so any φ sisters will also have a φ mother and be non-maximal.

-

(41)

The tableau in (42) shows the output of our revised grammar. As desired, the two winners, (a) and (b), phrase V and DP together, and (c) is harmonically bounded, because it violates StrongStart.

-

(42)

This analysis makes predictions about the distribution of troncamento in ditransitives. First, the DP should never undergo troncamento, because it is followed by a φ boundary in both winning candidates. Meinschaefer (Reference Meinschaefer2006) shows that this is the case: in (43a), the noun colore never undergoes troncamento. The account also predicts that verbs optionally undergo troncamento, because a φ boundary appears after the verb in candidate (b), but not in (a). Two native speakers confirm that both forms in (43b) are possible: troncamento optionally applies to the verb dare.

-

(43)

We have seen that an account of Italian ditransitives is possible with MatchOH, provided that we use the revised version of StrongStart in (41). An analysis using Elfner's MatchXP, in which any XP dominating a unique terminal string is visible, would select the wrong output. The empty-headed VP would be visible because it dominates the unique string [DP PP]. As shown in (44), this causes (c) to win: the desired winners, (a) and (b), incur an extra MatchXP violation because they fail to match VP. It is therefore necessary for the empty-headed VP to be invisible to MatchXPOH.

-

(44)

As noted earlier, the idea that XPs with silent heads are invisible is not unique to this analysis. In addition to Truckenbrodt's (Reference Truckenbrodt1999) work on Chicheŵa, Selkirk & Lee (Reference Selkirk and Lee2017) identify a similar issue in the phrasing of the double object construction in Xitsonga, and Kalivoda (Reference Kalivoda2018) shows that the ditransitive mismatch is ubiquitous cross-linguistically. Kalivoda's survey did not find a single language in which the two arguments phrase together to the exclusion of the verb, as would be predicted if the syntax were perfectly matched. To explain this mismatch, Selkirk & Lee (Reference Selkirk and Lee2017) propose MatchPhraseLex, which adopts Truckenbrodt's Lexical Category Condition by ignoring both functional phrases and empty-headed phrases; Kalivoda (Reference Kalivoda2018) follows suit in his Match-theoretic analysis of the phrasing of ditransitives in various languages. Thus the idea that empty-headed projections like VP are ignored by mapping constraints is not new, and is in fact assumed by many accounts enforcing a lexical/functional distinction.

The innovation here is to divorce the invisibility of functional XPs from the invisibility of XPs with silent heads. Although Truckenbrodt's Lexical Category Condition ties the importance of an overt head to the lexical/functional distinction, these are actually two separate issues. As argued in §5.1, categorically ruling out functional projections makes incorrect predictions in Italian. We therefore require MatchXPOH, which only sees XPs with overt heads but does not discriminate between lexical and functional projections. In the next section, I show that Subject + Verb sequences provide additional support for MatchXPOH.

5.2.2 Subject + Verb sequences

Recall from §3.2 that a preverbal subject phrases separately from the verb. In (45), the subject has final stress while the verb has initial stress, creating a potential stress clash, yet retraction does not occur. Both words also undergo lengthening. These facts support the phrasing in (45a), in which each word occupies its own φmax.

-

(45)

As explained in §4.1, I assume the subject has raised to a functional projection above TP, as in (46a) (Cardinaletti Reference Cardinaletti and Rizzi2004, Frascarelli Reference Frascarelli2007). Following Dehé & Samek-Lodovici (Reference Dehé and Samek-Lodovici2009), I relate the phrasing of the subject to its syntactic position. Crucially, MatchXPOH derives this phrasing without the lexical/functional distinction; reference to overt heads is sufficient. Matching DP and TP will place each ω in a separate φ, as in (46b). However, FP has a silent head and therefore will not be matched.

-

(46)

The tableau in (47) shows that the analysis generates this phrasing. Candidates (c)–(e) are eliminated because they fail to match DP, TP or both. Candidate (b) matches both DP and TP, but builds a φ corresponding to FP. This violates MatchφOH, because FP is invisible to the syntax–prosody mapping, and (b) is eliminated. Thus MatchXPOH is useful beyond ditransitives. (I omit Binmax(φ) and Binmax(ι) here, as none of the candidates violates these constraints.)

-

(47)

Adopting Elfner's MatchXP for Italian would again make the wrong predictions. MatchXP would try to match FP, because FP dominates a unique terminal string. The tableau in (48) shows that the subject and verb are incorrectly predicted to phrase together. The desired winner, (a), violates MatchXP by failing to match FP. Even worse, (b) harmonically bounds (a): (b) no longer violates Matchφ, because the φ containing both subject and verb is now motivated by FP. MatchXPOH is therefore necessary in Italian.

-

(48)

A reviewer asks if this analysis makes the undesirable prediction that the subject and the verb should always phrase together in languages in which the subject is in Spec,TP and the verb is in T, because verb raising renders TP visible to MatchXPOH, placing subject and verb in the same φ. The account does not make this prediction: there are several ways for a subject in Spec,TP to phrase separately from a verb in T while making TP visible. The first comes from Ito & Mester's (Reference Ito and Mester2019) discussion of Subject + Modal sequences in English, as in (49a). They propose that intermediate projections such as T′ are visible to MatchXP, because they are considered TPs according to bare phrase structure (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995). Ito & Mester predict that MatchXP prefers a structure like (c) over (b), such that the verb (and any complements) are mapped to a φ without the subject. It is therefore possible to match TP while phrasing the subject and verb separately.

-

(49)

A potential objection is that this mapping creates a φmax containing both subject and verb, and so they phrase together at some level. Ito & Mester anticipate this objection, using the rhythm rule as an example: non-application of the rhythm rule suggests that the subject and verb phrase separately in English, e.g. (Miˌchelle)φ (ˈcan)φ vs. *(ˌMichelle ˈcan)φ. They propose that the rhythm rule is a φmin diagnostic: at the φmin level the subject and the verb phrase separately, while at the φmax level they phrase together. Thus, when TP is matched but diagnostics suggest that the subject is phrased separately, the analyst can posit that these diagnostics are sensitive to a different level of φ structure.

Eurhythmic constraints may also overrule MatchXPOH, preventing TP from being matched. For instance, Binmax(φ) or Binmin(ι) could prevent the matching of TP, while still mapping the subject and T′ to separate φ's, as shown for the SVO input in (50). The perfectly matched candidate (b) violates Binmax(φ), because (SVO)φ dominates three ω's. Candidate (b) also violates Binmin(ι), because ι is unary branching. In contrast, (a) avoids violating the binarity constraints by phrasing S separately. If either constraint is ranked above MatchXPOH, (b) will lose, and the subject will phrase by itself. Making TP visible to MatchXPOH does not require the subject to phrase with the verb, and markedness constraints provide another way to phrase the subject separately.

-

(50)

While explaining the range of SVO phrasings is outside the scope of this paper, I have shown that subjects in Spec,TP can phrase separately from verbs in T in the approach adopted here. Moreover, the ingredients of this analysis have precedent. Analyses adopting lexical-only mapping constraints often assume that movement of a lexical word to the head of a functional phrase results in that phrase inheriting lexical status and becoming visible to mapping constraints; these analyses would also predict TP to be visible in languages with V-to-T movement (Samek-Lodovici Reference Samek-Lodovici2005, Dehé & Samek-Lodovici Reference Dehé and Samek-Lodovici2009, Göbbel Reference Göbbel2013, Kalivoda Reference Kalivoda2018). Previous work has also appealed to the subject's position to explain cross-linguistic variation in phrasing: in Romance and Bantu, the subject is argued to phrase separately when located outside of TP (Elordieta et al. Reference Elordieta, Frota and Vigário2005, Cheng & Downing Reference Cheng and Downing2009, Reference Cheng and Downing2016). Rather than making incorrect predictions, the MatchXPOH analysis retains the insights of previous work without invoking the lexical/functional distinction, which was shown to be problematic in §5.1.

The final ranking, presented in (51), was confirmed using SPOT (Bellik et al. Reference Bellik, Bellik and Kalivoda2015–21), a program that generates and evaluates all possible prosodic structures for a given syntactic input, and OTWorkplace (Prince et al. Reference Prince, Tesar and Merchant2017), which calculates factorial typologies and constraint rankings. The analysis uses a core set of Match Theory constraints, with only two revisions: Match constraints only see XPs with overt heads, and StrongStart is sensitive to prosodic subcategories.

-

(51)

6 Discussion

This study has analysed Italian in Match Theory. Empirically, the analysis shows that apparent φ phenomena do not completely overlap in their domains of application, supporting the existence of multiple phrasal domains. Theoretically, the analysis proposed MatchXPOH, according to which only overtly headed XPs are matched.

The argument for two phrasal domains was based on three processes: troncamento, stress retraction and final lengthening. While studies have claimed that troncamento is sensitive to φ boundaries (Meinschaefer Reference Meinschaefer2005), just as final lengthening and stress retraction are (Nespor & Vogel Reference Nespor and Vogel1986, Ghini Reference Ghini1993), I provided evidence that troncamento is sensitive to a smaller domain, contra Meinschaefer. I appealed to recursion and prosodic subcategories: troncamento is sensitive to any φ, but final lengthening and stress retraction are only sensitive to maximal φ. This analysis preserves Meinschaefer's insight that troncamento is sensitive to domains that often correspond to XP boundaries, while explaining why the three processes sometimes diverge.

This analysis relies on the idea that phonological representations can be recursive, which is not without controversy. There exist both Indirect Reference and Direct Reference models of the syntax–prosody interface that argue against prosodic recursion (Seidl Reference Seidl2001, Samuels Reference Samuels2009, Vogel Reference Vogel2009, Schiering et al. Reference Schiering, Bickel and Hildebrandt2010, Scheer Reference Scheer, Bloch-Trojnar and Bloch-Rozmej2012, among others). Although I analysed the two phrasal domains using recursion, an alternative account could posit another category in the prosodic hierarchy to explain why troncamento is sensitive to boundaries of a domain that is smaller than φ, but larger than ω. This approach could prove fruitful in frameworks that prohibit recursion, while acknowledging that Italian has multiple levels of embedding.