In the mid-1970s, US prison abolitionists, women of color feminists, and rape crisis advocates articulated the entanglement of sexual, racial, and state violence through the nationally publicized cases of four black, indigenous, and Latina women who had been charged with murder after defending themselves or their children from rape: Joan Little, Inez García, Yvonne Wanrow, and Dessie Woods (see Thuma; Law and Whitehorn). In July 1975, on the eve of the trial of Joan Little—the twenty-year-old incarcerated black woman who killed her white jailer Clarence Alligood when he attempted to rape her, something he had done with some regularity to other women detained at the Beaufort County Jail in Washington, North Carolina—Angela Davis wrote in Ms. magazine that the case revealed “the overt and flagrant treatment of women, through rape, as property” (“JoAnne Little” 154), originally “institutionalized during slavery” and “present today in such vestiges of slavery as domestic work” (155). In a July 1978 flyer, the New York Committee to Defend Dessie Woods—who had fought off the white serial rapist Robbie Horne with his own gun after he had posed as a police officer—called rape a form of “colonial violence”: “As the U.S. did in Vietnam, the state uses sexual violence against colonized women here in this country as a real weapon against the people as a whole.”

In the years leading up to these trials and the analysis of sexual violence they facilitated, James Baldwin had also been exploring the connections between state violence and sexual violence. As D. Quentin Miller has shown in detail, “involvement with the issue of incarceration was intensely personal [for Baldwin] during the late 1960s and early 1970s,” when both one of his lovers and one of his friends were in prison (137). This involvement included his directing of John Herbert's play Fortune and Men's Eyes while in Istanbul in 1969 and 1970; writing his nonfiction book No Name in the Street (1972), in part about the jailing and assault of his former bodyguard Tony Maynard; and fictionally adapting Maynard's story in his penultimate novel, If Beale Street Could Talk (1974). Baldwin's analysis was originally limited by his focus on incarcerated men. But Baldwin was also eager to connect the sexual assault of men in prison with the sexual assault of women both in and beyond prison in order to understand the state logics that provided their common infrastructure. Beale Street is about Tish and Fonny, a black couple who are engaged in Harlem when Tish becomes pregnant and Fonny is falsely accused of raping Victoria, a woman from Puerto Rico. No one in the novel disbelieves Victoria was raped; this is not an update to the story of the Scottsboro Boys. But Fonny is set up for the crime by the white police officer Bell, and while incarcerated Fonny and his friend Daniel both experience rape or the threat of rape themselves, rapes that reframe and extend the theorization of the rape Victoria experienced. Ultimately, Baldwin provided a detailed structuralist account of the function sexual violence serves for what we now call racial capitalism.

More specifically, Baldwin anticipates and converges two intellectual genealogies that would succeed him in thinking about the relation between violence—sexual violence in particular—and globalized colonial capital. In the first, the black radical tradition as further developed in the wake of Cedric J. Robinson's Black Marxism (1983), “racism enshrines the inequalities that capitalism requires,” as Jodi Melamed puts it (77). Building on the work of Michael Dawson, Nancy Fraser theorizes the color line as dividing those who are subject to “exploitation” under waged labor from those who are subject to “expropriation,” a form not of compensating but of “confiscating capacities and resources and conscripting them into capital's circuits of self-expansion” (166). In this view, “the expropriation of racialized ‘others’ constitutes a necessary background condition for the exploitation of ‘workers’” (168). The paradigmatic form of expropriation is enslavement, but under late capitalism it is also “[e]mbodied in the figures of . . . the migrant worker, the household worker, the chronically unemployed, and others like them,” as Nikhil Pal Singh elaborates (55). In Beale Street, Baldwin images the relation between expropriation and exploitation as one of scavenging: overworked “lawyers and bondsmen . . . circle around the poor, exactly like vultures” (7). The criminal legal system expropriates especially black and brown men to process, which gives public defenders and others labor to do that can be exploited (“they're not any richer than the poor, really, that's why they've turned into vultures” [7]). In a different context, building on what Vinay Gidwani and Anant Maringanti name the “waste-value” dialectic, Neferti X. M. Tadiar calls this the liquefication of the lives that racial capitalism has moldered, turning them into “disposable material whose management has become an entire ‘province of accumulation,’ spawning proliferating industries of militarization, security, policing, and control” (93).

In the second intellectual genealogy Baldwin preemptively refines, the Marxist feminist tradition that organized under the slogan “Wages against Housework” beginning in the 1970s, the emergence of capitalism similarly requires the expropriation of women's bodies. As Silvia Federici would later put it in Caliban and the Witch, the emergence of paid, productive, and thereby exploitable “free labor” required that the “female body [be] appropriated by the state and men and forced to function as the means of reproduction and accumulation of labor” (16). Under the “patriarchy of the wage,” women are excluded from productive labor, made dependent on men whose wages cover their own needs, and thereby conscripted into unwaged reproductive labor.

As Davis's aforementioned critique of waged domestic work as the afterlife of slavery suggests, a neatly gendered division between waged productive labor and unwaged reproductive labor often tacitly assumes a white family from which black and brown people have been pathologically expelled, perhaps most notoriously in Daniel Patrick Moynihan's racist 1965 report titled The Negro Family, which blamed black poverty on a failure of black heterosexuality. Certain theories of racial capitalism, for their part, are often obliged to admit their “incomplete character” because they exclude “gendered and familial forms of expropriation and exploitation” (Fraser 176). Where the two traditions often intersect is in engagement with Rosa Luxemburg's anticolonial extension of the Marxist rendering of “primitive accumulation,” now understood as the ongoing (not merely historical) means by which capitalism secures the conditions of accumulation through the colonial theft of lands and labor or the patriarchal theft of reproduction and care (see Day; Ince; Issar; Issar et al.; Nichols; Singh). In his prison writings from 1969 to 1974, Baldwin theorized how sexual violence is the premier method for these thefts constituted by the intersection of racial and gendered ascriptions. Moreover, he suggests a shift of emphasis in both feminist and racial capitalist paradigms by centering not just a gendered distinction between types of labor (productive versus reproductive), not just a racial distinction within productive labor (exploited versus expropriated), but rather a distinction defined by where race and gender intersect in determining for whom it is even possible to separate productive and reproductive labor in the first place.

For Baldwin, sexual violence is foundational and essential for racial gendered capitalism because it mediates between the two state-organized institutions tasked with securing the primitive accumulation and surplus value on which it relies: the family (and, more broadly, heterosexuality) and the prison (and, more broadly, policing). In this essay, I track the development of Baldwin's theorizing during this period, especially in the resonances and revisions moving from Fortune and Men's Eyes to No Name in the Street and finally If Beale Street Could Talk. Baldwin was particularly interested in what Ruth Wilson Gilmore might call the “distinct yet densely interconnected political geographies” of these two racial capitalist institutions (“Race” 261)—that is, how the state partitions but then dialectically enmeshes families and prisons on multiple scales: the domestic family home, the US prison, and the US colony of Puerto Rico.

Sexual Violence and the Double Labor Burden

In 1969 Baldwin was invited to direct Fortune and Men's Eyes in Istanbul by the theatrical couple Engin Cezzar and Gülriz Sururi. His directing style was unconventional, and not only because he spoke few words of Turkish. As Çiğdem Üsekes details in her account of his theatrical forays in Turkey, Baldwin frustrated his actors by sticking to a table read for almost three weeks instead of moving quickly to stage rehearsals (102). This deep attention to the words on the page—rather than to set, blocking, or staging—while sitting in a circle suggested that the author treated rehearsals like a literature seminar. He wanted his actors (students) to analyze the text itself, and out of his own close readings Baldwin found the beginnings of a unified theory of race, sex, policing, and capitalism.

Fortune follows four incarcerated young men over the course of several weeks as they share a cell in a Canadian reformatory. The newest arrival is Smitty, who learns that to avoid being assaulted by other inmates he will need the protection of a more powerful man. Rocky, described in the cast list as “a cornered rat, vicious, dangerous and unpredictable” (7), puts it to him this way: “You're a sitting duck for a gang splash if y'aint got an old man. I'm offerin’ to be your old man, kid” (Herbert 33). Smitty accepts the offer, as well as a cigarette lighter, without fully grasping the deal Rocky has proposed. By the end of act 1, the terms are clear. “So come on, baby,” Rocky tells him, “let's me an’ you take a shower before bedtime” (35). He takes Smitty to the shower room and rapes him.

In the relationship between Rocky and Smitty, Fortune presents rape as a skill for producing gender within a heterosexual idiom: the “old man” and his “baby.” In the quasi marriage that follows, Rocky acts as a breadwinner, exploiting “all kinds of lines goin’ around his joint” (34) and using the income to give Smitty gifts: “Ain't I good t'ya, kid?” (38). In return, Smitty's labor is domestic, serving Rocky in a cell explicitly called “the home” (28); in the scene following the first rape, for instance, Rocky orders Smitty to “[r]oll me some smokes!” (37). In the local newspapers covering the play in Istanbul, one formerly incarcerated individual commented on its realness: “In here, sex is one of those things, like cigarettes and marijuana, that facilitate business dealings” (qtd. in Üsekes 110). Moreover, sexual violence reduces intimate relationships to business dealings, establishing different forms of labor by stabilizing Rocky's participation in the prison market and Smitty's reproductive labor that allows for Rocky to participate in the market.

A background condition of this sexual division of labor within the couple, however, is another form of sexual violation that surveils those excluded even from the couple form. The exception that constitutes the norm is an androgynous person nicknamed Mona Lisa who refuses the “rules of the game” (Herbert 24), placing her outside the coupled bonds of sexual service and protection and leaving her subject to group violation: “They all took a whack, now she's public property” (23). The gang rape of Mona happened in the prison storeroom—the space in which other “public property” is held—and Rocky constantly reminds Smitty that he must stick with his “old man” if he wants to avoid “what happened to Mona in the storeroom” (23). Unlike Rocky's intimate rape of Smitty, the gang rape of Mona does not produce a gendered division of labor, but rather enlists Mona for both sides. She is still bossed around in the cell for unpaid domestic labor, but she is also referred to as “our little working girl,” earning petty wages “in the gash-house sewing pants together for the guys to wear” (20).

In an otherwise all-white cast, Mona was originally played by a black actor, Robert Christian, when the play premiered with the Little Room at the Actors Playhouse in New York City in 1967. Beginning with Davis's “Reflections on the Black Woman's Role in the Community of Slaves,” first published in the Black Scholar in 1971, US historians and theorists of racist institutions of confinement have called attention to the double labor burden of black women in particular, for instance on the plantation, where they were forced both to labor in the fields and to carry and nurse yet more laborers for the fields. So too in the institutions that extended slavery beyond its official terminus. In her groundbreaking history of punishment in the Jim Crow South, Sarah Haley explores the carceral institutions that were slavery's successors: convict leasing until the early 1900s; chain gang labor after that; and, beginning in 1908, the placement of imprisoned women in the private residences of white families to serve out the remainder of their sentences with domestic labor. As the chain gangs literally paved the roads to modernity and as imprisoned and then paroled women raised the families that would drive the new automobiles on them, “black women continued to face a double labor burden; they had to cook, mend, clean, and launder and also had to hoe, plow, dig, mine, saw, pull carts, blacksmith, and grade the street” (68).

Against this doubling of black women's roles, a new role emerged defined by its relative stability: the white woman. Unlike the black woman who could not legally be raped when enslaved and who was not believed as a rape victim when she was legally “free,” unlike the black woman who was required to labor both inside and outside the home, and unlike the black woman denied the privileges of private property on which to raise a family, the white woman supervised her domestic sphere and needed the protection of white men. Fortune gives form to a similar dynamic, securing the space of the cell “home,” with a heterosexual division of labor enforced through intimate partner rape, in contrast to the space of the “storeroom,” where Mona is made into “public property” through gang rape. The storeroom is a prison within the prison, and the violence of this prison, a violence that is “public” in the sense that it belongs to an institution of the state, is a background condition encoding the violence against Smitty as domestic, enfolded within the “private” institution paradigmatically called the family.

In Beale Street, Baldwin explores this interface between public state violence and private domestic violence through the experience of Daniel, a childhood friend who recently reconnected with Fonny and Tish after his release from a two-year sentence in prison. Like Fonny, who will be blamed for a crime that occurs but that he did not commit, Daniel was fingered for a car theft after being picked up for simple marijuana possession. Before Fonny's arrest, Daniel starts coming over to Fonny's place for evening drinks and talks about his traumatizing experience in prison: “Daniel was trying very hard to get past something, something unnamable” (109). Because sodomy is the paradigmatic “love that dare not speak its name,” it is implied that this “unnamable” something is sexual in nature, but it is not revealed that he was raped in prison until the novel's end. In the meantime, its narration gets sublimated into a more familiar tropology of domestic violence. This is, after all, a domestic scene organized by a traditional gendered division of roles—the men talk while Tish makes dinner—and the specter of harm enters the scene through the possibility of gendered difference becoming gendered violence. Daniel compliments Tish's good looks, to which she playfully responds:

Fonny's muttered threat of domestic violence in response to the flirtation between Daniel and Tish is made generic by Daniel's invoking the lyrics of “My Man,” a song about a woman in love with a man who “isn't true / He beats me, too.” Originally a French ballad, the song was made popular in the United States earlier in the twentieth century with a recording from Fanny Price, but Daniel, Tish, and Fonny are listening to the 1951 jazz recording by Billie Holiday. Their collective breaking into song does not just impersonalize the tension between Fonny and Tish by making it generic, it also regenders domestic violence by bringing the men into the speaking position of the battered woman.

The three laugh after their performance of the verse, until “Daniel sobers, looking within, suddenly very far away. ‘Poor Billie,’ he says, ‘they beat the living crap out of her, too’” (104). This toggling between laughter and dead seriousness is intrinsic to domestic abuse itself, the way in which a joke (Daniel's flirting with Tish) could erupt into violence (Fonny's retaliating out of jealousy), and the way in which the threat of violence itself becomes a joke (Fonny wouldn't really do such a thing). Nonetheless, Daniel's departure from the joke also marks his inability, unlike Fonny and Tish's, to stand completely outside it. He recognizes himself not only as the teller but as the butt of the joke; he identifies with Billie by conflating domestic violence with police brutality and prison assault. Because domestic violence is stereotypically “violence against women” and police brutality and prison abuse are stereotypically “violence against men” (Douglass 109), Daniel and Billie move into a space of what Patrice D. Douglass has called “black gender,” which theoretically “dismantles the predicate of gender” (116); instead of opposing “men” and “women,” and by extension police violence and intimate partner violence, black gender highlights the “intimate relationship between state violence and women of color, specifically Black women, as constitutive of gender violence” (114). Both domestic violence and police violence occur and are sanctioned within state institutions, whether marriage or prison.

The first chapter of Zakiyyah Iman Jackson's Becoming Human centers on Paul D, from Toni Morrison's Beloved, who develops an attachment to normative heterosexual manhood as a recompense for being repeatedly raped by white guards on a chain gang; this attachment is a “cruel optimism” (Berlant) because that manhood is “itself based on his vulnerability to gendered and sexual violence,” and normative heterosexuality is constituted through racial exclusion so that its pursuit “can only reinforce black gender as failed or fraudulent” (Z. Jackson 76). For Jackson, what is important is how Morrison “desentimentalizes this loss of identity by framing loss as an invitation to invention, such that the loss of manhood, the relinquishment of what never properly belonged to him and compelled renegotiations of identity, becomes the arc of Paul D's development as a character” (66). So too does Daniel connect his experience and Billie's so that his response to victimization in prison is not to seek an impossible masculinity premised on the control of women's bodies but rather to imagine solidarity through the shared position he and she occupy in a racial capitalist structure. But unable themselves to make this connection at the time, Fonny and Tish respond to Daniel's sobering observation by looking away: Fonny through platitudes (“we just have to move it from day to day” [Baldwin, If Beale Street 104]) and Tish through redirecting toward the domestic setting (“Let's eat” [105]). The return to domestic heterosexuality disavows the earlier threat of violence within domesticity. In this way, Beale Street repeats Fortune's contrast between the violence experienced in the institution of the prison and the violence possible in the institution of the family. Just as the excessive violence against Mona backgrounds the intimate violence against Smitty that forces him into heterosexual labor roles, Daniel's experience facilitates the emergence of domesticity between Fonny and Tish. Although Melinda Plastas and Eve Allegra Raimon have shown that Beale Street offers up homosocial intimacy as an “antidote to male-on-male violence” in prison (690), this violence also becomes a resource, raw material to be processed, for the production of normative heterosexuality.

Fortune also explores this kind of analysis: beyond counterposing the “home” of the cell with the internal prison of the “storeroom,” the play also theorizes how the institution of the family outside prison requires as a background condition the exceptional violence for which the prison provides a scene. The guard who oversees the four inmates “beats his wife an’ bangs his daughter,” creating gender through sexual violence on the model of Rocky and Smitty (Herbert 47). Toward the end of the play, the guard also informs the four men that the prison sergeant and his wife have shown up for the “Christmas show” that the incarcerated put on each year: “The General's wife and the Salvation Army are out there tonight” in the audience. The Christmas show is essentially a drag show; music provides a “nightclub atmosphere” (69), and throughout the play the inmates are told to save their “vaudeville” for when they “do your number at the Christmas concert” (13). The telos of the play is finally a Christian ritualized event in which a homosocial cast of incarcerated men perform heterosexuality for an audience of state officials and their wives—that is, an audience of official heterosexuality, what Hortense J. Spillers might call the master's “house” to which the men behind bars are “vestibular” (67).

While directing Fortune, Baldwin learned that the division between the prison and the family is colonial. The royal sergeant's “English accent” is actually the first voice heard in the play, after an overture sung by a boys’ chorus, and the incarcerated men explain the sergeant's colonial credentials: “He's always going on about the ‘Days of Empire’ and ‘God and Country’ and all such Bronco Bullcrap” (Herbert 13). He often taunts new inmates into fights, the most memorable instance being a man of Iroquois descent who accepted the offer to box, only to be beaten up by a team of guards. We do not learn the name of the Iroquois man, who is often referred to by way of his relation with indigenous women, as in “Pocahontas’ husband” and, even more pejoratively, “that squaw-banger” (14). It seems the man had come from the nearby Matachewan Reservation to “get a job in the mines,” became involved in a violent interaction with a policeman during a workers’ riot, and was subsequently jailed.

Before the drama of the play unfolds, Fortune thus establishes the space of the prison as an essential means of colonial expropriation. First, the mining on which the Matachewan economy relies, beginning with the discovery of gold in 1916, required the displacement of First Nation peoples; the prison remains a space for absorbing this now surplus population. Second, the prison severs relations of kinship—“Pocahontas’ husband”—that would allow for the state-recognized accrual of capital and by extension intergenerational financial stability. The prison divides the recognized heterosexuality of the sergeant from the aspirational heterosexuality of the inmates. That the sergeant remains offstage throughout the entire play means that the space of the prison is organized by both his absence and his lurking colonial presence. He invites racialized conflict but withdraws from its engagement, leaving the inmates themselves to play out the racial drama of aggression and submission, sublimated as sexual. The space of detention forms a prototype for a state that sets up a marketplace through the threat of colonial violence but removes itself from reciprocal violence by redirecting it into the marketplace itself, including the subject positions of “old man” and “baby” that mark economic roles within it (nonincarcerated individuals, too, are coerced into coupling when the “family wage” and the tax breaks of marriage may be required as a condition of surviving capitalist exploitation). It both pressures the family with domestic violence as the sublimation of state violence and polices who gets to even be part of a family through a “supplemental . . . violence that might best be called cruelty or extreme violence,” to borrow a formulation from Chandan Reddy (235).

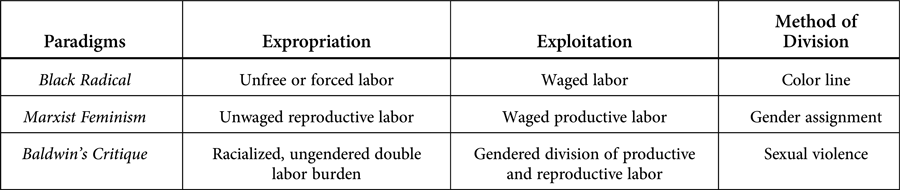

A double function thus emerges for sexual violence in racial capitalism. Within the family, intimate partner rape conscripts a victim into reproductive labor. But before the family—just as in both the black radical and the Marxist feminist traditions there is a space of expropriation before capitalist exploitation of “free labor”—there is a space of “public” assault that conscripts its victims into a double labor burden, both low-wage service work and nonwage reproductive labor (table 1; I follow Robert Nichols in disaggregating Enteignung, or expropriation, from the larger “modular package” of primitive accumulation [69]). Moreover, fear of the public rapist—whether the looming threat of the gang in Fortune or the myth of the black rapist in the US imaginary—covers the rape internal to the family, providing an alibi for the guard's and sergeant's sexual exploitation within the confines of the “private.” Beale Street, in particular, reflects on how the family form, especially before marital rape became criminalized, marks a space of privacy in which violence is both common and protected. Tish worries, “I was his and he was mine—I suddenly realized I would be a very unlucky and perhaps a dead girl should I ever attempt to challenge this decree” (Baldwin, If Beale Street 77). And even though officer Bell's wife “hates him,” spousal privilege forbids her to testify against her husband (120).

Table 1. Dividing Expropriation from Exploitation across Three Paradigms

Rape and History's Ass-Pocket

According to Magdalena J. Zaborowska's account in James Baldwin's Turkish Decade, it is uncertain if Baldwin knew that Mona had originally been played by a black actor (151). But in the years following his directing of Fortune, Baldwin found a resonance between the gang rape of Mona and the experience of his former bodyguard and friend Maynard, who was arrested in Hamburg in early 1968 and charged with the murder of a US marine in New York City the previous spring. Baldwin flew to Hamburg to assist Maynard, hire him a lawyer, and provide emotional support throughout his incarceration. On one visit, Baldwin learned Maynard had been assaulted. He had requested a guard return his “religious medallion” (Baldwin explains that Maynard had “become a kind of Muslim, or at least, an anti-Christian”); the guard “jumped salty and he walked out. And I started beating on the door of my cell, trying to make him come back, to listen to me, at least to explain to me why I couldn't have it, after he'd promised. And then the door opened and fifteen men walked in and they beat me up—fifteen men!” (qtd. in Zaborowska 424).

In the final pages of Beale Street, Maynard's experience of racist and Islamophobic retaliation is given to Daniel, when the abuse he experienced in prison is revealed: “He had seen nine men rape one boy: and he had been raped” (Baldwin, If Beale Street 174). The nearly identical syntactic structure of Daniel's revelation—the gang nature of the perpetrators; the plain description of the perpetrators as merely “men” instead of clarifying guard or inmate or someone else; the simple structure of subject, assaultive verb, and victim; and the repetition after a break, whether a colon or an em dash—suggests Baldwin codes Maynard's experience as a rape, or at least it becomes rape in Beale Street. At the same time, for Maynard the perpetrators (“fifteen men”) are repeated and not the victim; but for Daniel the victim (“he”) is repeated and not the perpetrators. The effect is to make the presence of the perpetrators more spectral, which is also to say more scenic. What matters in the aestheticization of Baldwin's journalistic report of Maynard's speech is not the fact of the men but the fact of a scene in which rape happens and recurs: the prison. Moreover, the substitution in Beale Street of a period for an exclamation point suggests the quotidian, not exceptional, nature of this scene—how ordinary this violence is for the functioning of the larger social order.

On a previous night, Daniel had begun to tell his story, beginning with his arrest. The police came across Daniel after he had bought some marijuana that “was in my ass-pocket. And so they pulled it out, man, do they love to pat your ass, and one of them gave it to the other and one of them handcuffed me and pushed me into the car” (107). The eroticization of power through police groping is buried in a dependent clause in this sentence, but it becomes more explicit on the following page when Daniel recalls being locked up in a cell that night with a young black man who is going through a painful drug withdrawal: “[The] mothers who put him in this wagon, man, they was coming in their pants while they did it. I don't believe there's a white man in this country, baby, who can even get his dick hard, without he hear some nigger moan” (108). The analysis recalls, but departs in one significant way from, Baldwin's earlier short story “Going to Meet the Man” (1965), in which a white sheriff, unable to get it up for his white wife, fantasizes about degrading a black woman, although this is revealed, in flashbacks, to be a sublimated arousal. Earlier in his career, the sheriff had beaten up a black civil rights leader, “began to tremble with what he believed was rage,” and then “to his bewilderment, his horror, beneath his own fingers, he felt himself violently stiffen” (235). The phrase “violently stiffen” captures as succinctly as possible the sheriff's convergence of sex and brutality, the degradation of the black man being the true object of his arousal—although this arousal is misunderstood as rage. But even this is a displacement of a primary fantasy revealed in the story's final flashback, when the sheriff remembers attending a lynching as a boy. There, looking at the “beautiful” and naked hanging body, “he began to feel a joy he had never felt before” (247); the boy who would become the sheriff “felt his scrotum tighten” as he looked at the man's genitals (248). This memory of a white man's sexual awakening (“a joy he had never felt before”) is both an attraction to the black man and a disavowal of this attraction through ritual violence.

When Daniel says a white man's erection requires a black man's “moan”—where moan's double signification conflates sexual pleasure and physical pain—he suggests that underneath sadism is a gay panic, overcompensation for the earlier desire to “pat your ass.” But when he tells the story of his prison rape, what matters is the absence of a sheriff or another panicked subject from the scene. The effect is to remove a subject onto which an easy psychoanalytic reading can be projected. Unlike “Going to Meet the Man,” Beale Street provides a rape but not a rapist to psychoanalyze. The effect is to make the analysis of rape's causes more institutional than psychological: rape becomes the effect not of the individual psyche but of the institution that regularizes its practice. This is something Baldwin learned from Fortune, too; in a directorial note, he wrote that the play's sexual violence was meant to “ruthlessly [convey] to us the effect of human institutions on human beings” (qtd. in Zaborowska 175).

The grabbing of Daniel's “ass-pocket” also echoes No Name in the Street, when Baldwin documents his own experience of sexual victimization at the hands of a white man, most likely an officer or elected official of the state (who could, Baldwin writes, cancel or ensure a lynching with a phone call): “With his wet eyes staring up at my face, and his wet hands groping for my cock, we were both, abruptly, in history's ass-pocket” (390). On one level, the metaphor of being in “history's ass-pocket” refers to how the fantastic sexual subjugation of the black man has been outside official history; as Kevin Birmingham puts it, “we admire history's clothing and decline to check its pockets—especially the back ones” (142). But on another level, the sexual charge of the “ass-pocket”—not only in the urban gay vernacular of the handkerchief code but in the erotics of the ass itself—suggests that the space outside official history is also the history of sexuality, at the same time that the history of sexuality is outside sex itself. Marlon B. Ross puts it this way: “History's ‘ass-pocket’ . . . is not quite the same as history's asshole. History's ass-pocket is . . . the highly sexualized but frustratingly unfuckable dead end” (633).

Baldwin may also have a more colloquial sense of the ass-pocket in mind. First, to have something in one's back pocket is to have a trick up one's sleeve: an emergency resource held in reserve. Second, to be in someone's back pocket, which is where a wallet might be kept, is to be under their control, usually financially, as in being bought off. To substitute “ass pocket” for “back pocket” is to retain these meanings while sexualizing them. By putting his event of sexual assault in “history's ass-pocket,” Baldwin suggests that history always has rape as a reserve resource that can produce value when necessary, while also indebting perpetrators and victims to history's own good graces. As black feminists writing on the afterlife of slavery, including Spillers, Saidiya V. Hartman, and Christina Sharpe, have long theorized, and as Jesse A. Goldberg has read Baldwin's No Name in the Street in particular (see Goldberg 529–30), the US symbolic order “remains grounded in the originating metaphors of captivity and mutilation so that it is as if neither time nor history . . . shows movement,” as Spillers originally put it (69). These theorists usually read the connection between slavery and incarceration as a continuous story not of forced labor but of fungibility, “not labor relations, but property relations” (Sexton 36); “the continuity of the chattel relation does not pivot on the reproduction of the ‘involuntary servitude’ as prison labor,” Dylan Rodríguez explains, “but rather on the subjection of targeted, criminalized beings to a carceral logic of anti-Blackness that renders them available as fungible chattel” (205). Baldwin, however, emphasizes the function of sexual violence in securing a double labor burden, which includes the reproductive labor of repairing one's self in the wake of trauma—a labor that is about sustaining the body to be “available,” in Rodríguez's words, not just for more labor but for more speculation: the profit made off of moving a body through courts, hospitals, and prisons. Baldwin suggests that rape specifically is a permanent tool for the creation of racialized gender, adapting to the needs of the contemporary wallet.

In Beale Street, Baldwin brings this out in two ways, one dealing with the experience of Daniel, who was raped, and the other with the experience of Fonny, who was falsely accused of rape. For Daniel, the trauma gives him emotional work to do: “Daniel brought it out, or forced it out, or tore it out of himself as though it were torn, twisted, chilling metal, bringing with it his flesh and his blood—he tore it out of himself like a man trying to be cured” (106). The convergence of “metal” and “flesh,” though used metaphorically, also recalls the strenuous productive labor Daniel does with a dolly: “I gotta slave . . . in the garment center, pushing a hand truck, man” (98). The trauma of rape predisposes Daniel for low-wage labor after incarceration, labor he is forced to accept in order to do the emotional work of tearing his trauma out of him. Just as capitalism's enclosures of public goods, from land to resources to care, make private citizens have to work harder to reclaim them as property bought with a wage, so too does rape's theft of Daniel's bodily integrity make him have to work hard to become what we have come to call a survivor. This too is a kind of double labor burden, the burden of both reproducing himself each day and producing enough in a capitalist world to afford to do so.

The false accusation against Fonny also serves history's wallet by divorcing him from private property and the means of its intergenerational bequeathal. Spillers describes this as a creation of “kinlessness” (74), and as Jennifer L. Morgan has noted more recently, the offspring of an enslaved person was not her family but a vessel for further development of a master's profits, so that the enslaved women's “capacity to gestate a child meant that she carried the market inside her body” (222). Under a late-twentieth-century order of racial capitalism, Baldwin reads rape's enmeshment with state violence as a continued force for creating kinlessness, not unlike how in the middle of her discussion of kinlessness, Spillers briefly turns from Frederick Douglass to the Autobiography of Malcolm X, which narrates El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz's own kinlessness in his dual relationship to state institutions of confinement: first, the mental institution that took his mother as a child, and, second, the prison in which he was himself incarcerated. Early in Beale Street, before Fonny has been sent to prison, Tish reflects on a heterosexual division of labor on her street: “The kids are home from school. The men are home from work. . . . And this drives the women, who are cooking and cleaning and straightening hair and who see what men won't see, almost crazy” (Baldwin, If Beale Street 26). This heterosexuality is certainly no ideal in Baldwin's mind; the women's emotional distress suggests the exploitation Baldwin sees within the family form. But the charge of rape enters the novel to sever access to even this exploitative, rather than expropriative, institution.

In particular, Baldwin shows how both the myth of the black male rapist, perpetuated in order to incarcerate him, and the rape of black men while incarcerated manufacture a kinlessness that grounds a double labor burden for black women. While incarcerated, Fonny “is placed in solitary for refusing to be raped” (192). This split geography, between the general population and solitary, recalls Fortune's split between the patriarchal cell and the storeroom, but whereas in Fortune the storeroom rape of Mona enlists her into double labor, in Beale Street resistance to rape produces social death, a removal even from the possibility of the tortuous “old man and baby” kinship we saw between Rocky and Smitty. However, the most important departure of Beale Street from Fortune or No Name is its focalization of the story not through Fonny but through Tish. Centering Tish, Beale Street emphasizes how the black man's removal from sociality is contagious beyond the confines of the prison. First, the racialized accusation of rape separates families: “We were going to get married, but then he went to jail” (Baldwin, If Beale Street 5). When Tish visits the office of Fonny's white lawyer, the difference in family status is immediately apparent, as she notices that “on the desk, framed, were two photographs, one of his wife, smiling, and one of his two small boys. There was no connection between this room, and me” (93). Second, rape gives women a job to do, coercing them into productive labor in addition to “cooking and cleaning and straightening hair.” Tish works at a department store's perfume counter (39); when they need more money to advance Fonny's case, Tish's sister Ernestine “has to spend less time with her children because she has taken a job as a part-time private secretary to a very rich and eccentric young actress” (128). Both are employed in low-wage service work that, notably, serves white women. Rana M. Jaleel has theorized that “the work of rape is the generation of value,” in part through how states name and respond to different forms of rape (26); it is also the work of rape to generate work—and different types or amounts of work based on state responses to different types of harm.

Tish and Ernestine are living in a period in which black women in particular bore what Priya Kandaswamy has called the “domestic contradictions” of a state ideology that routes citizenship and material support through the unit of the family but keeps the family out of reach for many black people because of wage suppression, redlining, and other state practices of racism. Introduced in 1967, the Work Incentives Program became mandatory in 1971, requiring recipients of aid to families with dependent children to seek and accept work as a condition of support. Disproportionately black in real numbers and universally black in the national imagination, a “good mother” receiving welfare now became defined as someone who left her children at home in order to labor in the workforce, in contrast to the “good” white suburban housewife domiciled in the private home. Just as Daniel's rape gives him a double labor burden after prison, predisposing him to both low-wage productive work and the reproductive work of emotional self-repair, Fonny's accusation of rape and his resistance to rape in prison mandate a double labor burden for his severed kin.

The Colony of Sexual Violence

Baldwin's foregrounding of male survivors of rape may raise questions of his relation to what Michele Wallace called the “macho” force of the Black Power movement. In 1979, Wallace's Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman criticized Beale Street and No Name for their deification of the black phallus (62). More recently, critics have suggested that Beale Street “mawkishly extolled the virtues of heterosexual love” (Clark 58) or is “utterly phallic and patriarchal” (Murray 32). In most cases, critics see this focus on heterosexuality as in part Baldwin's overreaction to homophobic attacks from authors such as Eldridge Cleaver (see Field 73; Mills; Newton). What this line of argumentation misses is the potential queerness of both Beale Street and “black macho” culture itself; the Black Panthers had, after all, embraced as an advocate Jean Genet, who wrote the introduction to George Jackson's Soledad Brother and whose career had been built on novels of gay sex and gay rape in prisons (see Sandarg). I therefore follow Lynn O. Scott's invitation that Baldwin's later works “not be read as evidence of either a political capitulation or an artistic decline, but as evidence of the ways Baldwin creatively responded to a changing racial environment and discourse” (174). At the same time, it is true that, having read Cleaver's Soul on Ice and Jackson's Soledad Brother, Baldwin had the instinct to explore state violence by beginning with the incarcerated black man.

The final innovation of Beale Street, however, is to consider the effect of sexual violence on women in the larger colonial context in which Baldwin had begun to see it. Fonny's experience in the novel replicates many details from Maynard's story in No Name that were not given to Daniel: the false accusation for a crime that happened but that he did not commit; a flimsy case based on the testimony of one white man who apparently is able to identify Maynard's passport photo seven months after the fact; the sudden departure of the “logical eyewitness” (Baldwin, No Name 421)—in Beale Street, the rape survivor Victoria Sanchéz and, in No Name, a “young sailor” who was present at the time of the murder (417). Other details diverge too, most importantly the fact that unlike Maynard's, Fonny's lawyer is able to track down the eyewitness, eventually to Puerto Rico, where Tish's mother goes to confront her. This addition, which occupies much of the last third of the novel, signals Baldwin's increased awareness of rape's colonial function.

To Puerto Rico, Baldwin brought what he had learned of US imperialism while directing Fortune in Turkey. Baldwin's time there coincided with increasing anti-American sentiment, sparked in part by the so-called Johnson letter of 1964, which became public in 1966. Following Cyprus's independence in 1960, its constitution recognized a division between its two major ethnic communities, Greek and Turkish, mandating that the president be elected by the Greek community and the vice president, who had significant veto power, be elected by the Turkish community. By 1963, this bicommunal system had reached a constitutional deadlock, and in December violence erupted between the communities, displacing more than 25,000 Turkish Cypriots from their segregated villages and pressuring the Turkish prime minister Inönü to intervene. As violence escalated and Turkish military intervention into Cyprus seemed increasingly likely, President Johnson sent a telegram to Inönü on 5 June 1964. In the patronizing letter, Johnson reminded Inönü of his responsibility “to consult fully” with the United States on military matters, stressing Turkey's responsibilities as a NATO member. At the same time, he warned Inönü that intervention in Cyprus could lead to conflict with the Soviet Union and that “your NATO Allies have not had a chance to consider whether they have an obligation to protect Turkey against the Soviet Union if Turkey takes a step which results in Soviet intervention.” Johnson concluded: “You and we have fought together to resist the ambitions of the communist world revolution. This solidarity has meant a great deal to us.”

To many Turks, the implications were clear. Turkey served an ideological function for the United States as a buttress against “communism.” Its role was to perform in a capitalist market. But in return, the United States would offer no material support, not even protection of people in the Turkish diaspora against violence. Global capitalism simultaneously required Turkey's consent and required that Turkish people and lands ultimately be fungible and disposable; multilateralism was imperialism by another name, leading to the impoverishment of non-US peoples. This, to many audiences of Fortune's run in Istanbul, was what the play was finally about; the producer Gülriz Sururi “saw the brutalities depicted in the play as reflecting the lives of the Turkish poor,” and she “focused emphatically on class issues rather than individualism of desire, choice of partners, and sexual identity” (Zaborowska 157).

In the Turkish press, the lack of self-determination made it seem as if Turkey, or at least Cyprus, was essentially a territory of the United States, governed by its own imperial foreign policies (see Bolukbasi). Laura Briggs has shown that Puerto Rico, an actual US territory and an island almost exactly the same oblong shape and size as Cyprus (both 3,500 square miles), served a similar function of coupling ideological peonage and material negligence during the Cold War: “Puerto Rico became (largely through massive federal government subsidies) a political showcase for the prosperity and democracy promised by close alliance with the US” (2). In particular, the policies referred to as Operation Bootstrap rapidly converted Puerto Rico's economy from agricultural to industrial, with two main effects on Puerto Ricans’ labor population. First, those pushed out of the traditional economy fled to the mainland, and especially New York City, for employment, again leading to a kind of kinlessness while “produc[ing] a low-wage labor force on the mainland that could be pushed back to the island in times of hardship” (112). Second, the United States incentivized industrial employment of low-wage labor on Puerto Rico itself, prototypical of “the current situation, whereby virtually all manufacturing for US markets is done in the Third World” (18).

One year after the Moynihan Report had blamed black poverty on matriarchal family structures, Oscar Lewis's La Vida: A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty—San Juan and New York (which won a National Book Award in 1967) transferred blame for the entrenched poverty that resulted from a colonial manipulation of labor onto Puerto Rican women, in particular with the stereotype that they produced too many children. In Beale Street, Victoria bears this burden. She is painted as sexually irresponsible, a single mother of three children whom she leaves on the mainland after fleeing to Puerto Rico with her boyfriend Pietro, not the father of her children (Baldwin, If Beale Street 117). But from the perspective of Baldwin's analysis of the relation between rape and racialized families, it is better to say that rape produces a kind of kinlessness for Victoria, introducing a trauma that separates her from her children. Moreover, the trauma of rape sends Victoria back to Puerto Rico, indicating her ultimate disposability for the capitalist system she supports, not unlike how Turks saw the abandonment of their kin in Cyprus by the US government. As Gilmore's Golden Gulag teaches us, the prison is one place to absorb surplus populations. So too is the colony: when large-scale migration of women to the mainland—especially the migration of Puerto Rican women—led to an overaccumulation of labor that made the women and their wages disposable, rape was a way of sending them back, a phenomenon that feminist internationalists like Verónica Gago have more recently linked to the “femicidal machine” that emerged around Ciudad Juárez's multinational maquiladoras following the 1993 passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which incentivized manufacturing companies previously given breaks in Puerto Rico to move their low-wage jobs to Mexico (21).

What Baldwin thereby theorizes in Beale Street is how the accusation of rape against the black man Fonny and the actual rape of the brown woman Victoria provide a similar function for racial capitalism. Like prison rape, the rape of Victoria also produces kinlessness and monitors the division between exploitative and expropriative forms of labor. In Puerto Rico, the trauma of losing her children eventually causes Victoria to be removed from a San Juan favela to the rural mountain region of Barranguitas, allegorizing a movement from the new industrial economy to the old agricultural one. Like the warehousing of Fonny in prison, the warehousing of Victoria in the mountains turns people into fungible property that produces value by being moved around and manipulated by state institutions.

In a more optimistic ending, Baldwin might have suggested their functionally similar experiences could be grounds for an alternative, cross-racial kinship, and the novel does gesture in this direction at earlier moments. For instance, Baldwin uses the same language of being on a “garbage heap” to describe the black youth of Harlem (If Beale Street 36) and the youth of Puerto Rico (185). And while roaming the corridors of the jail, Tish hypothesizes that a common affective experience might provide a kinship among the relatives of the incarcerated: “I've never come across any shame down here, except shame like mine, except the shame of the hardworking black ladies, who call me Daughter, and the shame of proud Puerto Ricans, who don't understand what's happened” (7). But by the end, Baldwin shows that this kinship is barred by a colonial structure. When Tish's mother, Sharon, comes to Puerto Rico looking for Victoria in order to ask her to change her testimony, she is essentially asking Victoria to do the emotional work of reliving the trauma of her rape in order to heal Sharon's family. Victoria refuses to do this reproductive labor, insisting, twice, on the priority of her own productive labor: “Excuse me, Señora, but I have work to do” and “Señora—! I have told you that I have my work to do” (165). Sharon attempts cross-racial solidarity, calling Victoria “Daughter,” but in this favela, which is “far worse than what we would call a slum” (129), all the locals cannot help reading her nationality before reading her race: “Her only option is to play the American tourist” (147) because to them she “looks like a Yankee—or a gringo—tourist” (149). She cannot avoid the imperialist position she holds while in Puerto Rico; as Brian Norman puts it in his reading of Beale Street, “Sharon cannot inhabit both her location as an American tourist and a fellow subjugated citizen” (125).

In her recent work on reimagining black feminism, Jennifer C. Nash has called for increased “intimacy” between the paradigms of intersectionality and transnationalism, spotlighting how intersectionality might “attend to the variety of ways—globally—that the state's antidiscrimination apparatus becomes a critical tool in entrenching and reproducing violent harm against marginalized bodies” (107; see also Dillon). Baldwin's contribution to this project is to consider how the interlocking scales of this violent harm become fractal. Cumulatively, Baldwin's engagements with sexual violence, prisons, and kin from 1969 to 1974 present a fractal picture of rape's relation to racial capitalism: a similar logic that repeats on larger and larger self-containing scales. Within the prison of Fortune and Men's Eyes, there is a storeroom where gang rape makes Mona into public property that serves a double labor burden, and there is a patriarchal cell in which intimate partner rape conscripts Smitty into feminized labor. But on an enlarged geographic scale, both the storeroom and the cell are part of the same prison in which gender is plastically manufactured in contrast to the space of the nonincarcerated family where the sergeant's sexual violence again produces the role of his wife. Daniel reflects on this interface when he compares his gang rape in prison with the intimate partner rape Billie Holiday sings about in “My Man.” On the ultimate geopolitical scale, Sharon, Tish, Ernestine, and Fonny similarly aim to secure a family in contrast to the expropriated space of the colony, a lesson in US imperialism Baldwin learned in Turkey but stages within Beale Street in Puerto Rico. While on the mainland, it looks as if those in the kinless orbit of Fonny are tasked with a double labor burden. On the neocolonial scale, though, it looks more as if they are just doing the reproductive labor of trying to preserve their family, in contrast to the double labor burden they ask of Victoria to aid them.

On each scale of analysis, a colonial color line, policed by sexual violence, divides the exploitative space of gendered labor roles (prototyped by the family) and the expropriative space of a double labor burden (prototyped by the prison). In a different multiscalar context—considering how those economically exploited in the Global North look better off when compared with anyone in the Global South—Aarthi Vadde has written that “[c]onfronting relative privilege is not about implying, exposing, or judging contradictions in financial status and political conviction as evidence of hypocrisy. Rather, it is the discomfiting but essential position from which to think about how national and global scales of inequality fit together” (184). So too does Baldwin track the self-similar logic of racial capitalism across different colonial scales of sexual violence in order to see their interlocking nature.