The United States is a multiracial democracy. It consists of groups with diverse interests, various cultural practices, and competing political agendas. These groups are not static and the American population is undergoing rapid changes to its racial demographic landscape. Recent projections show significant shifts on the horizon: whites are expected to become a numerical minority, while racial minorities are to become the majority by the year 2045 (Frey, Reference Frey2018). Scholars in political science and related fields show that when this growing number of racial minorities are made salient to the American public, it prompts racially discriminatory attitudes (Danbold and Huo, Reference Danbold and Huo2015; Craig and Richeson, Reference Craig and Richeson2018). One of the fastest growing racial groups, Asian Americans, have been given minimal attention in the study of racial threat from demographic changes. Crucially, in American society, Asian Americans have recently been perceived in a threatening light. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been large upticks in discrimination against Asian Americans (Noe-Bustamante et al., Reference Noe-Bustamante, Ruiz, Lopez and Edwards2022). As such, it is crucial to understand the dynamics of how racial threat from Asian Americans operates.

In this project, I assess the efficacy of the activation of racial threat from Asian Americans, and assess its implications for white Americans' political attitudes. I show that threat from Asian Americans motivates white Americans to simultaneously become less perceptive of discrimination toward Asian Americans, while also causing them to become increasingly supportive discriminatory policy which targets Asian Americans.

I then show that this sense of racial threat generalizes, across multiple, salient policy areas. As a first test of threat from Asian Americans, I prime this idea using a survey experiment in an exit poll on a convenience sample of American voters in the 2018 Midterm Elections. In this study I assess how this threat alters support for discrimination in the context of a salient education policy issue, which was the suit that eventually led to the Supreme Court decision in Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College. I conduct the same study years later with a representative sample of white Americans, replicating these same findings from the first study, then go even further by showing that racial threat from Asian Americans also leads to more support for policy that discriminates against Asian Americans in the context of COVID-19.

Ultimately, I conclude that Asian racial threat can perniciously function in a way that leads to shifting views of discrimination. I show evidence of how racial threat can create an environment that facilitates more discrimination on a mass level, while simultaneously reducing perceptions that discrimination is increasing. Additionally, in the study of racial threat, this work serves as a call for more distinct and robust focus on perceptions of Asian Americans within the mass American public.

Racial threat theory involves the challenge of a minority racial group to the status of a majority group (Wirth, Reference Wirth1941). The idea is “[a] fear and suspicion that the subordinate race harbors designs on the prerogatives of the dominant race” (Blumer, Reference Blumer1958, 4). Scholars have shown that as the size of minority groups increase, so does prejudice which is expressed by the majority group toward the minority group. This happens for two reasons: (1) increased competition over scarce resources, and (2) the greater number of minority group members that can be politically mobilized (Blalock, Reference Blalock1967). In both of these ways, the growing size of the minority group is perceived to encroach on the majority groups' status.

While scholars who study American public perceptions of racial demographic change have demonstrated that threat is felt from information about the diversification of the United States, they do not call to what inferences that white Americans might be making about these changes. That is, white Americans' perceptions of the changing country might not meet reality. In this project, I seek to ground the perceptions of the changing racial composition of the US in reality. I investigate how priming white Americans with information about the fastest increasing racial group, Asian Americans, affects their threatened responses. While some racial minority groups might come to mind, in reality, Asian Americans actually are the fastest growing group in the US (Tavernise, Reference Tavernise2018). This is important as a focus of the study of racial threat because white Americans are likely to come across this information, especially as Asian Americans continue to increase in size.

Contextually, the relationship of Asian Americans to the dynamics of racial threat is important yet understudied. Recent increases in hate crimes against Asian Americans and increasing negative attitudes toward Asians underscore the importance in better of understanding how this distinct type of racial threat can emerge (Noe-Bustamante et al., Reference Noe-Bustamante, Ruiz, Lopez and Edwards2022; Rios Reference Rios2022). I argue, much of the group-specific question of Asian racial threat begins from better understanding of their group status in American society.

1. Asian group status

As a racial group, Asian Americans are incredibly diverse. Researchers have long articulated that this diversity is central to the racial structure of the group: “Diversity is the hallmark of the contemporary Asian American community” (Zhou and Gatewood, Reference Zhou and Gatewood2000). This diversity exists along ethnic, class, and language lines, just to name a few (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Lien and Margaret Conway2005). On ethnicity, “Asian American” encompasses Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Filipino, Indian, Vietnamese, and a series of other origin groups (Budiman and Ruiz, Reference Budiman and Ruiz2021).

Despite these large differences across the racial group, Asian Americans have often been “lumped” together into a single racial category (King, Reference King2000; Nugraheni and Hastings, Reference Nugraheni and Hastings2021). The lumping is partly attributable to the US Census establishing the racial category of “Asian American” (Hirschman et al., Reference Hirschman, Alba and Farley2000). The lumping of Asian Americans is also attributable to “ignorance of their diversity or for political gain [among Asian Americans]” (King, Reference King2000). The diversity of Asian Americans as a racial group is important to acknowledge, lumping occurs especially when Asian Americans are brought into comparison with other racial groups.

In American racial dynamics, Asian Americans are a higher status minority racial group, relative to Black Americans and Latinos. The higher status of the group motivates stereotypes of Asian Americans as the “model minority myth” (Lee, Reference Lee1994; Choi and Lahey, Reference Choi and Lahey2006; Wong and Halgin, Reference Wong and Halgin2006; Maddux et al., Reference Maddux, Galinsky, Cuddy and Polifroni2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Wong and Alvarez2009; Zhang, Reference Zhang2010; Poon et al., Reference Poon, Squire, Kodama, Byrd, Chan, Manzano, Furr and Bishundat2016; Zou and Cheryan, Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). The myth is simple: Asian Americans are stereotyped to be hard-working and high achieving, especially when compared to other racial minorities. This achievement is touted as something positive about the group, and thereby is used to demonstrate to other racial minorities that they should model their behavior more in line with Asians to see similar success.

Scholars have found that this myth is typically projected with implicit anti-Black motivation—that is, if Black Americans worked as hard as Asian Americans, they would see more success as a group. The myth is also used in the same vein to undercut ideas that other minorities are discriminated against. The view is that Asian Americans are a minority group that is, apparently, not held back by discrimination, therefore all other racial minorities are not either and should follow the example of Asians. These stereotypes partially motivate particular types of threat that I expect Asians will elicit among white Americans.

2. Contingent threat types

I anticipate that threat, as it relates to Asian Americans, is contingent upon two things. First, it will be contingent on the salient stereotypes that exist about the group. Second, I also expect that the stereotypes about Asians are more likely to be affected by changing contexts, which is driven by the heterogeneity of the racial group. The lumping of the variant identities of Asian Americans together leads to a situation where the boundaries of the racial group are more porous than other racial groups within the US. Scholars have previously shown context to be vital in also explaining ingroup identity among Asian Americans (Junn and Masuoka, Reference Junn and Masuoka2008). For these two reasons, I take a granular approach to pursuing racial threat in this project.

Each of the following variants of threat has been investigated in previous works; however, all three have not been brought together within a single study. All three describe a type of power contestation that racial demographic change could bring—i.e., economic, cultural, and political (Blalock, Reference Blalock1967).Footnote 1

First, economic threat involves the perception of the direct fiscal harm a minority group can pose, either to one's own pocketbook or to the economy as a whole (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004). For example, one might feel economically threatened by an immigrant group that is perceived to be job competition. Thus, competition over scarce resources is what motivates economic threat.

Second, cultural threat involves the perception that a group poses harm to what it means to be American (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Hartman and Taber2012). An individual who feels culturally threatened might worry that an increase in non-English speaking immigrants will decrease the amount of English spoken in the US, and thereby alter their way of life. Control over cultural influence motivates cultural threat. Within previous studies, this sentiment has often been referred to as “status threat” (Mutz, Reference Mutz2018).

Third, political threat is the perception that a group will have a negative effect upon the political system (Hawley, Reference Hawley2011). Following from Blalock (Reference Blalock1967), political threat is a sense of threat about the increasing political mobilization capacity of a growing minority group. As minority groups increase in size, more can mobilize for the sake of their own causes, which will in turn diminish the political influence of the majority group. I specifically investigate whites' sense of threat from Asians, and how it moves their political attitudes about discrimination. I discuss my rationale for looking into Asians next.

3. Expectations

I expect that when whites learn that Asians are increasing in size as a racial group, they will feel more economically threatened (H1). The model minority stereotype will be generalized outward to Asians as a group. Through this inference in the aggregate, Asians will be seen as more threatening in the realm of economic success—e.g., because the growing group will be able to compete for more higher-paying jobs.

I anticipate that the growing size of Asians will not affect white Americans' perceptions of political and cultural threat as strongly. In line with the model minority stereotype, Asians are perceived to be near-equal competition for white Americans on the job market. Connected to this same stereotype, Asian Americans are not perceived to encroach on the dominant American culture because they are culturally peripheral (Jo Reference Jo1984; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Kwan, Cheung and Fiske2005; Maddux et al., Reference Maddux, Galinsky, Cuddy and Polifroni2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Wong and Alvarez2009). The distance that Asians as a group had from ideas of encroaching on white Americans' cultural and political status will lead to a lesser effect of their growing size on cultural and political views of threat.

I anticipate when white Americans learn of the projected growth in Asian Americans, they will express more negative feelings both toward Asian Americans and proximate groups (H2). This expectation calls to a generalized racial threat, where the negative feelings that are generated toward a specific racial group are expanded to other related groups. Specifically, I expect that whites will feel threat from Asian Americans which will cause them to generalize their negative feelings to immigrants overall. My rationale here is that Asian Americans are stereotyped as “perpetually foreign” (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Wong and Alvarez2009; Huynh et al., Reference Huynh, Devos and Smalarz2011) and that the negative sentiment which comes from threat leads to negative evaluations of immigrants (Hood and Morris, Reference Hood and Morris1997; Alba et al., Reference Alba, Rumbaut and Marotz2005; Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008).

These first two expectations motivate my central expectation about discriminatory attitudes. Threat will relax white Americans' perceptions about Asian American targeted discrimination (H3) while simultaneously causing white Americans to become more supportive of discriminating against Asian Americans (H4).

For H4, I capture the discrimination in the form of policy that discriminates against Asian Americans. My expectation is that support for this policy will increase among threatened whites because it will be viewed as a measure to curb the encroachment of Asian Americans on whites' group status (Blumer, Reference Blumer1958). In tandem with the idea that motivates H3, whites will be less keen on perceiving that the group is discriminated against, while actively engaging in more support for discrimination.

Experimentally, I show how racial threat can facilitate a more discriminatory public and society. I identify threat leads to a dynamic relationship of perceptions of discrimination, where discrimination can increase while perceptions of it decrease. This suggests that, in an environment like the United States, while acts of discrimination against Asian Americans are on the rise, threatened white Americans will also perceive the racial environment to be getting better over time. I argue that racial threat sets forth a vicious cycle of the continuation, and potential worsening, of discrimination over time.

4. Anti-Asian discrimination and threat

One of the most prominent areas where stereotypes about Asian Americans take root is in higher education. For this reason, I use a salient political issue concerning college admissions as my first case in this project. In 2015, a group of Asian American students who were denied admission to Harvard University filed a lawsuit alleging discrimination. The group cited evidence that Asian American applicants were limited admission because of their race, which would be illegal (Gluckman, Reference Gluckman2018; Hartocollis, Reference Hartocollis2018). They asserted that evidence showed that a quota was set for the number of Asian American students admitted, which the Supreme Court has ruled to be unconstitutional (Sedler, Reference Sedler1977; Seeger, Reference Seeger, Stone, Rutledge, Polly, Anthony and Xiaoshuo2016). I investigate the effect of threat on the two elements that are pertinent to this lawsuit. The first element captures perceptions of discrimination, namely the idea that Asian Americans have been discriminated against in university admissions (testing for H3). The second element assesses support for the idea of setting a racial quota on Asian applicants (testing for H4), the very practice deemed unconstitutional because it discriminates against Asian applicants (Liptak and Hartocollis, Reference Liptak and Hartocollis2022; Writer, Reference Writer2022).

I operationalize threat from Asian Americans from information about US Census projections about changing racial demographics through multiple survey experiments. These projections show that Asian Americans are the fastest increasing racial group in the US (Tavernise, Reference Tavernise2018). These projections serve as the treatment within this experiment. As a prime this mirrors previous experiments which show that similar information about racial demographic change generates racial threat in robust ways, but have not shown this in the context of specific racial groups (Craig and Richeson, Reference Craig and Richeson2014a, Reference Craig and Richeson2014b; Abascal, Reference Abascal2020).

I administer my first experiment using an exit poll during the 2018 US Midterm Elections in Northbrook, Illinois. I collected these data over the course of two weeks from 22 October 2018, to 6 November 2018.Footnote 2 I subset on white Americans in my following analyses (see Appendix 1 for sample demographics).

My motivation behind the use of an exit poll and the location is twofold. First, I want to look at opinion of politically active white Americans because their policy views have the most immediate relevance. For this reason, I implement this study in the context of an exit poll. This context makes this study a hard case for shifting political attitudes. Because of the implied political participation from the exit poll, respondents are more likely to have established political views and to be primed to be thinking about politics. As such, their attitudes are more stable than others less invested in thinking about politics.

Second, I chose Northbrook, Illinois as the location to field this study because the population of this town fits the parameters of a place where white Americans are strongly primed to feel racial threat from Asian Americans. I wanted to test opinion of whites who might be the most immediately affected by an increase in Asian immigrants. Due to this motivation, I conduct this study in an area where whites are the majority group and Asians are essentially the only minority group. The backdrop of the community I selected to conduct this study highlights an important potential interplay between perceptions and tangible racial composition conditions. I expect that participants will be better able to process an increase in Asians within their community, which will help control for the novelty of an increase in their size. In communities lacking a large presence of Asian Americans, threat from the Census projection about their increasing size could be confounded by the novelty of the information. I expect that information on Asians being the fastest increasing immigrant group will cause white Americans to become less supportive of the idea that Asians experience discrimination, while simultaneously more discriminatory toward Asian Americans. Next, I detail my first study procedure, then move to describing the results.

5. Testing racial threat and attitudes toward Asian American discrimination

First, respondents filled out a poll with general demographic questions. Then, in the final pages of the survey, they encountered the experimental questions. This design consists of two groups, the treatment and control. As mentioned, the treatment primed racial threat from Asian immigration to the US.

All respondents in this study were asked the following question which set up the prime,

Which immigrant population do you think has been the fastest growing in the U.S. over the past six years?

Latin American | Asian | European | African | Northern American | Other

Then, the treatment group turned over the page to the poll and read the following,

Interestingly, the correct answer to the prior question is Asian—this was confirmed by a recent U.S. census report. That report also projects that Asian immigrants will be the largest immigrant population in 2040. Footnote 3

The control did not receive this same information. Both groups, upon turning the page, then responded to a series of outcome measures that measured racial threat (H1), feelings about different racial groups (H2), and attitudes regarding discrimination in the Harvard lawsuit (H3–H4). Next, I discuss my results from this first study (for the full instrument, see Appendix 2).

6. Study 1 results

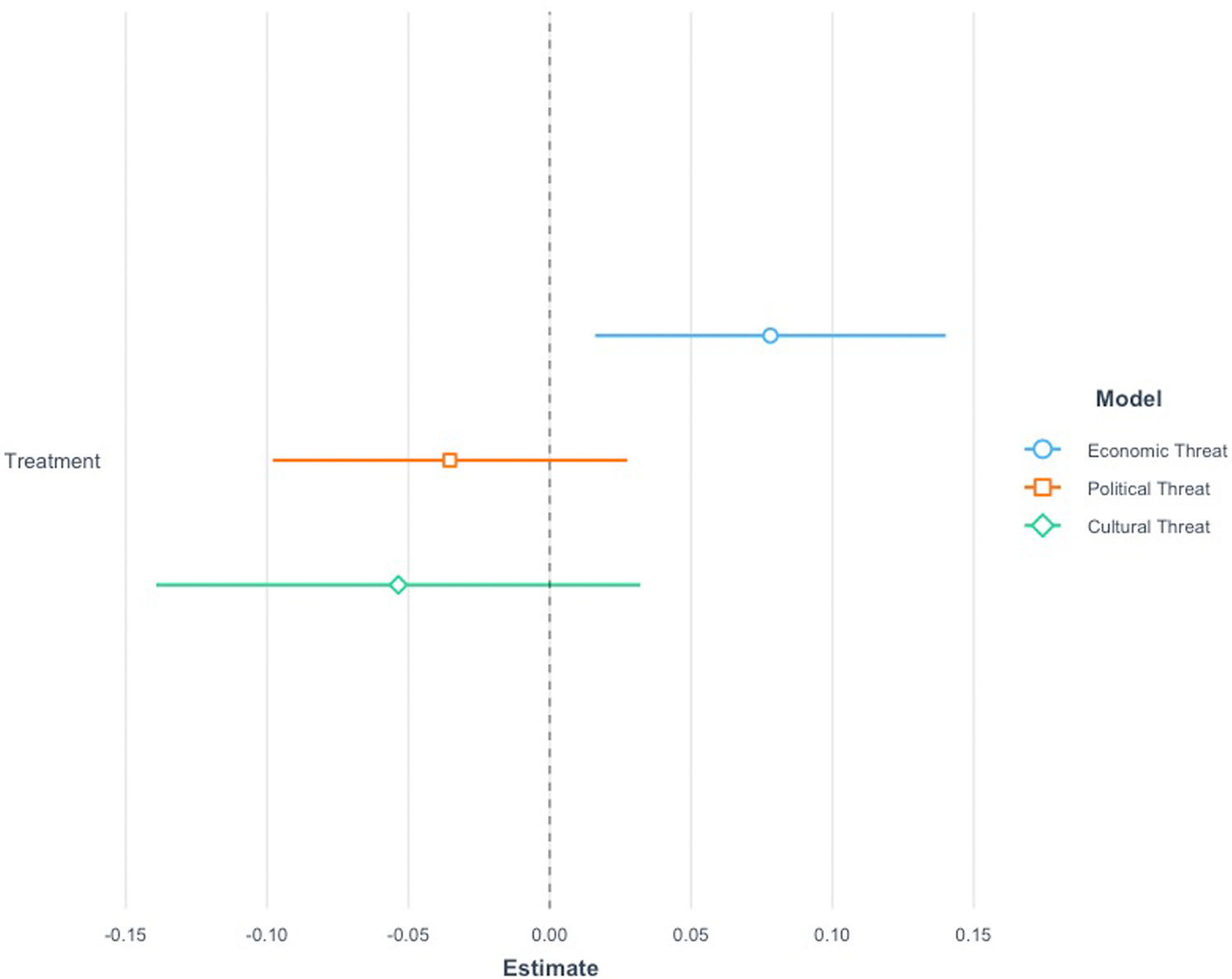

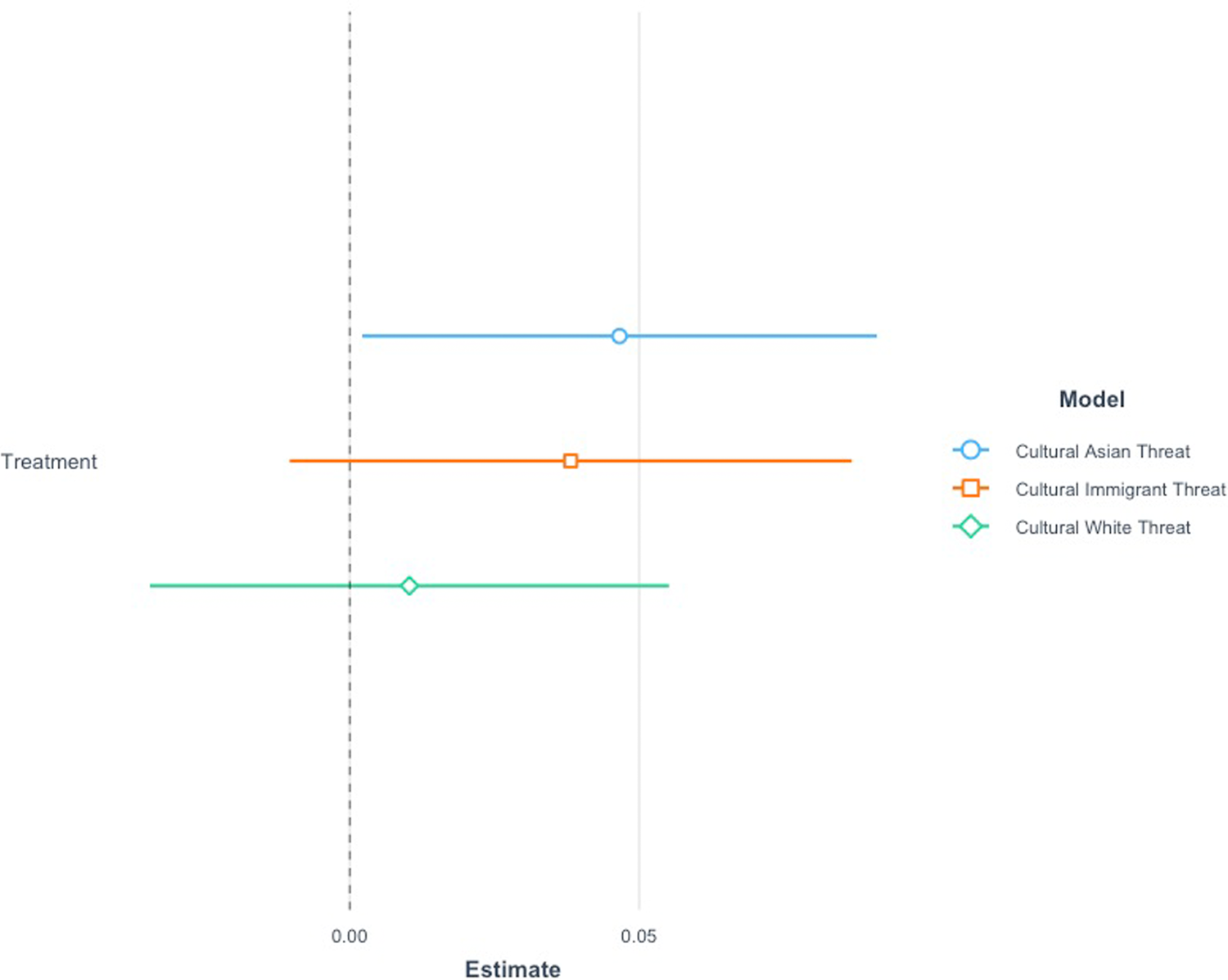

I start by testing H1—which is the expectation that the projected increase in the US Asian population will generate feelings of economic threat among white Americans (for balance tests and power analyses, see Appendix 3.1). I use linear regression to analyze the effect of the Census projection, controlling for a series of demographic variables.Footnote 4 Ultimately, I confirm that the Census information generates economic threat only (8 percentage point increase, p = 0.01). Comparatively, the same projection has an insignificant effect upon both political (p = 0.26) and cultural (p = 0.21) senses of threat (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of census information on senses of threat.

These three findings all in tandem confirm H1. As I expected, racial threat from Asians causes more economic concern and is isolated along this axis of threat. Stereotypes about Asian Americans as the model minority do well to explain the multiple components of this finding. Here, I find evidence that white Americans could be generalizing this stereotype onto the threat felt by Asian Americans on the whole, which is why these views motivate economic threat exclusively in this first study.

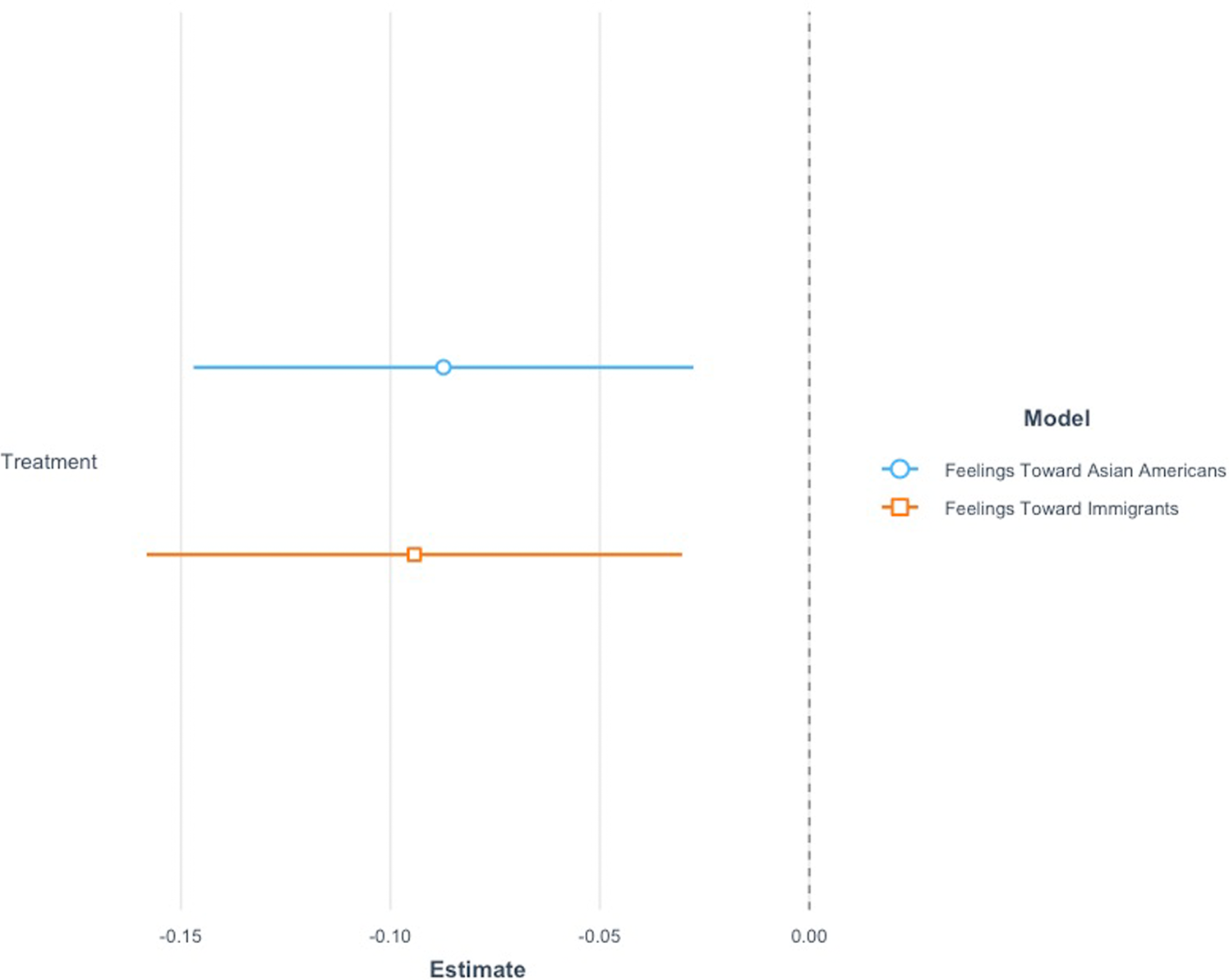

I turn next to testing H2, which is the idea of generalized racial threat wherein whites' feelings about Asian immigration spreads onto related groups, specifically I test for feelings toward all immigrants. My two key measures for H2 are feeling thermometers on Asian Americans and immigrants (Appendix 2).

I confirm H2. The Census projections that Asians are the fastest increasing immigrant group cause white Americans to feel significantly colder toward Asian Americans (9 percentage points colder, p < 0.01) and immigrants (9 percentage points colder, p < 0.01), shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Effect of Asian racial threat on feelings toward Asian Americans and immigrants.

White Americans seem to move their feelings about Asian Americans to immigrants on the whole. That is, when they feel threatened by Asian immigration, it has implications for how they think about all immigrants. Importantly, the effect of the racial prime has a similar magnitude on feelings about Asian Americans and immigrants. This finding also lends support to the notion that Asian Americans are “perpetually foreign” in the sense that they are never seen as assimilated as Americans (Huynh et al., Reference Huynh, Devos and Smalarz2011).

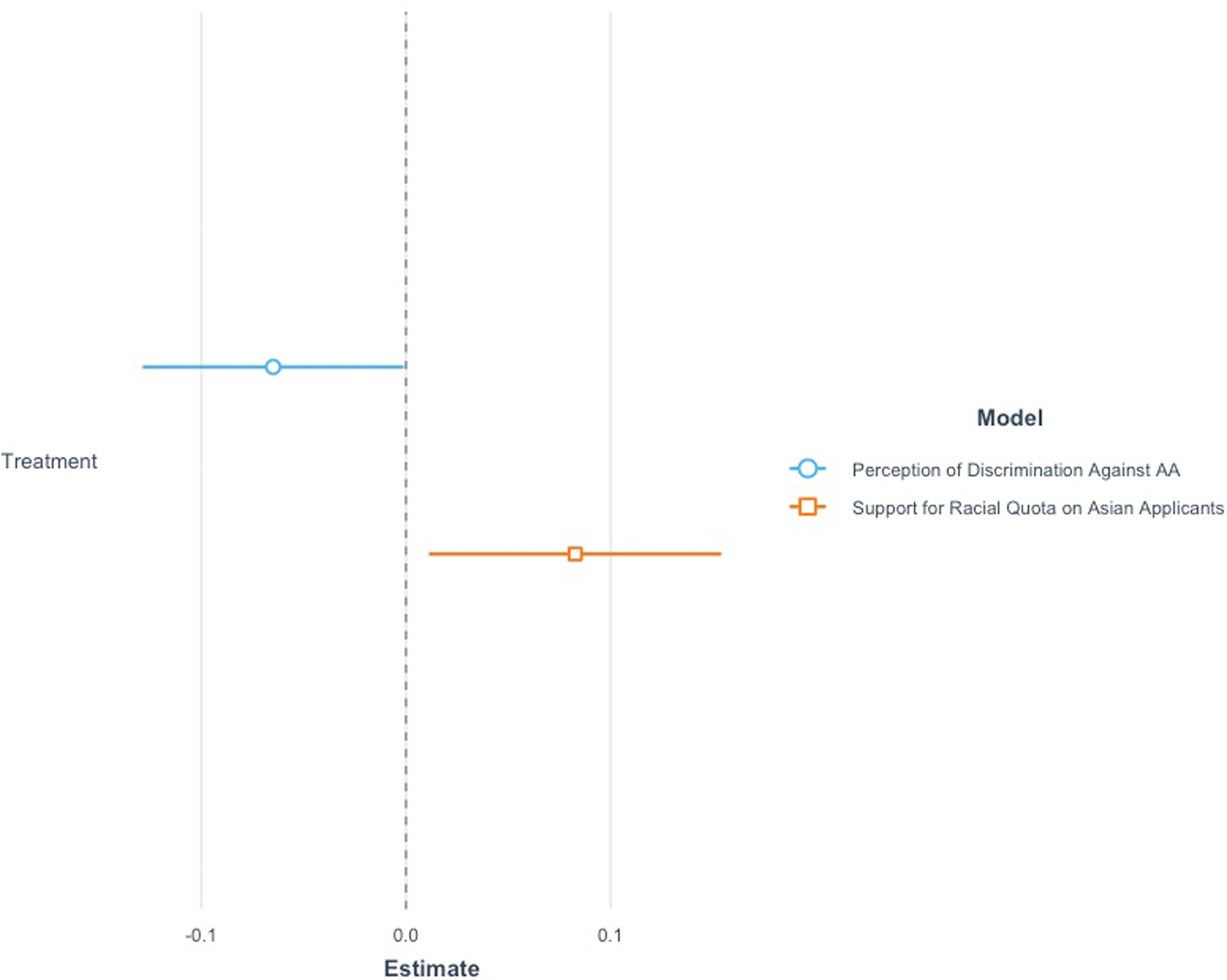

Finally, in study 1, I test specific attitudes about Asian American discrimination (Figure 3). This I do within the context of the Harvard lawsuit leveled by Asian American applicants. The measures I use are support for the idea that Asians were discriminated against in university admissions (testing for H3), and support for setting a racial quota on Asian applicants to university (testing for H4). As a final contextual point of importance, the issue of the Harvard lawsuit was at peak salience when this first study was fielded (see Appendix 3). Regarding the salience of the case, I find this context to create a more difficult case for detecting any effect of threat on perceptions of the case because it is more likely that Americans were familiar with the issue. Beliefs and attitudes about the case were thus “stickier” and less likely to change (Clemons et al., Reference Clemons, McBeth, Peterson and Palmer2020).

Figure 3. Effect of Asian racial threat on perceptions of discrimination.

My findings confirm my expectations on how threat affects attitudes about discrimination (H3–H4). Threat from Asian Americans causes whites Americans' perceptions of Asian American discrimination to decrease (6 percentage point decrease, p = 0.04), while also increasing their support for policy that actively discriminates against Asian Americans (8 percentage point increase, p = 0.02).

7. Study 1 discussion

Overall, the results of this study have multiple important implications. The projections about Asian Americans increasing in size specifically generate economic threat.Footnote 5 This threat motivates larger negative group feelings and strongly shifts views of Asian American-based discrimination.

For further validation of the efficacy of racial threat shifting discriminatory views, I show through mediation analyses that this economic threat is likely a mediator in the shifting policy attitudes toward the Harvard lawsuit (Appendix 4). Using the Imai et al. (Reference Imai, Keele and Yamamoto2010) approach, I find that economic threat accounts for a great deal of the treatment effect. There are a series of limitations in the use of mediation analysis (Bullock et al., Reference Bullock, Green and Ha2010; Green et al., Reference Green, Ha and Bullock2010). To account for these, I include the possible confounders in my model. These are party identification, income, gender, and education. Economic threat as the mediator (ACME in the models) explains a large amount of the effect of the treatment. The consistent and strong relationship between economic threat and discriminatory attitudes helps to better identify the causal pathway.

This study reveals that racial threat can change interpretations of ongoing events and perceptions of how racial groups are treated—likely because people form negative evaluations of the group that is discussed and that shapes their perspective. Racial threat from Asian Americans leads white Americans to express more negative views of immigrants on the whole. It is suggestive that racial threat from specific immigrant groups could lead to larger anti-immigrant sentiments across the American public. For example, when American elites use inflammatory rhetoric about Asian Americans, it could likely lead to decreasing views toward all immigrants in the US. Additionally, seemingly nonthreatening conversation about Asian Americans increasing in size could lead to more xenophobic attitudes toward all immigrants. Further research should be conducted to determine if other immigrant groups also lead to more negative general immigrant attitudes.

On a larger societal level, I show here that Asian American racial threat also alters larger views of discrimination in pernicious ways. By decreasing support for the idea that Asian Americans are being discriminated against, while also increasing support for active policy discrimination, it sets up a scenario for increasing anti-Asian attitudes and behavior. Threat causes a relaxed sense of whether Asian Americans are being singled out in college admissions, but despite this, it leads white Americans to want to set racial quotas on Asian American applicants. Connecting this discrimination to other domains, the dynamic I show in study 1 helps to describe the uptick in hate crimes toward Asian Americans in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, while there was a simultaneous dearth of coverage of this surge of discrimination.

This first study gives indication that this dynamic is plausible. As a larger and more robust test of these effects of threat, I expand the scope of its effect on discriminatory views into the context of COVID-19 in study 2, which I discuss next.

8. Asian American threat extended

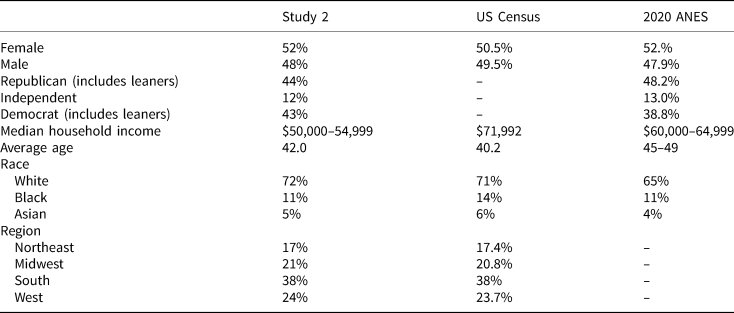

My second study expands on study 1 in multiple ways. First, it replicates study 1 using a larger, representative sample of the American public. This sample is census matched on gender, race, region, and age and was fielded through Qualtrics. To replicate study 1, I subset on white Americans (N = 732, for regressions, power analyses and balance tests, see Appendix 5.1) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study 2

To replicate study 1, I use the same treatment that primes the Census information about Asian Americans along with the same outcome measures for feeling thermometers and on perceptions of discrimination. In the midst of this same study, I go further by expanding measures of threat.

I measure for the different types of threat, which was a test of H1, across Asians and related groups which was H2. To reiterate, my expectation in H1 was that Asian racial demographic change would generate a sense of economic threat; and my expectation in H2 was that threat would lead to more negative views toward Asians and groups related to them. By combining these two measures, I am able to isolate whether white Americans are feeling particularly economically threatened by Asians, as well as isolate whether senses of threat are generalized onto related groups. Regarding proximate groups, I test for senses of threat toward Asians, Latinx Americans, and immigrants because of the proximity of these groups based upon associations these groups have with immigrants (Oliver and Wong, Reference Oliver and Wong2003).

This study was conducted in 2020 which is crucial to how racial threat from Asian Americans is operating. Due to the shifting salience of Asian Americans within the COVID-19 pandemic, I expect that the Census projections will cause white Americans feel greater senses of threat from Asians across economic, cultural, and political lines (H1b). Because of the large increase in anti-Asian xenophobia in the American public, I anticipate this shift in sentiment will motivate a greater overall feeling of threat when the group is primed (Lee and Waters Reference Lee and Waters2021). Following from dynamic of proximate groups to Asians being disliked more, I anticipate white Americans will also feel greater senses of threat across all measures from immigrants.

As a third extension, I test support of another anti-Asian discriminatory policy that is in the context of COVID-19. This policy specifies the discriminatory targeting of Asian Americans in the midst of the pandemic.Footnote 6 I analyze support for (1) “forcibly testing Asian Americans for COVID-19” and (2) “forcibly testing Asian immigrants for COVID-19” (Appendix 5 for detailed measures).

My separation of these groups is another explicit test of the “perpetually foreign” stereotype that I found to influence white Americans' feelings toward immigrants within study 1. I separate measurement of each of these groups in order to substantively parse out perceptions of Asian Americans and Asian immigrants. However, I expect that white Americans will not distinguish their feelings toward Asian Americans and Asian immigrants, which will confirm my expectation that Asian Americans are perceived as perpetually foreign. Ultimately, I expect the threat felt from the Census projections will again shift white Americans' discriminatory views, thereby causing them to become more supportive of policy proposals that explicitly target Asian Americans and Asian immigrants (H2b). Next, I move to examining my results.

9. Extending Asian racial threat

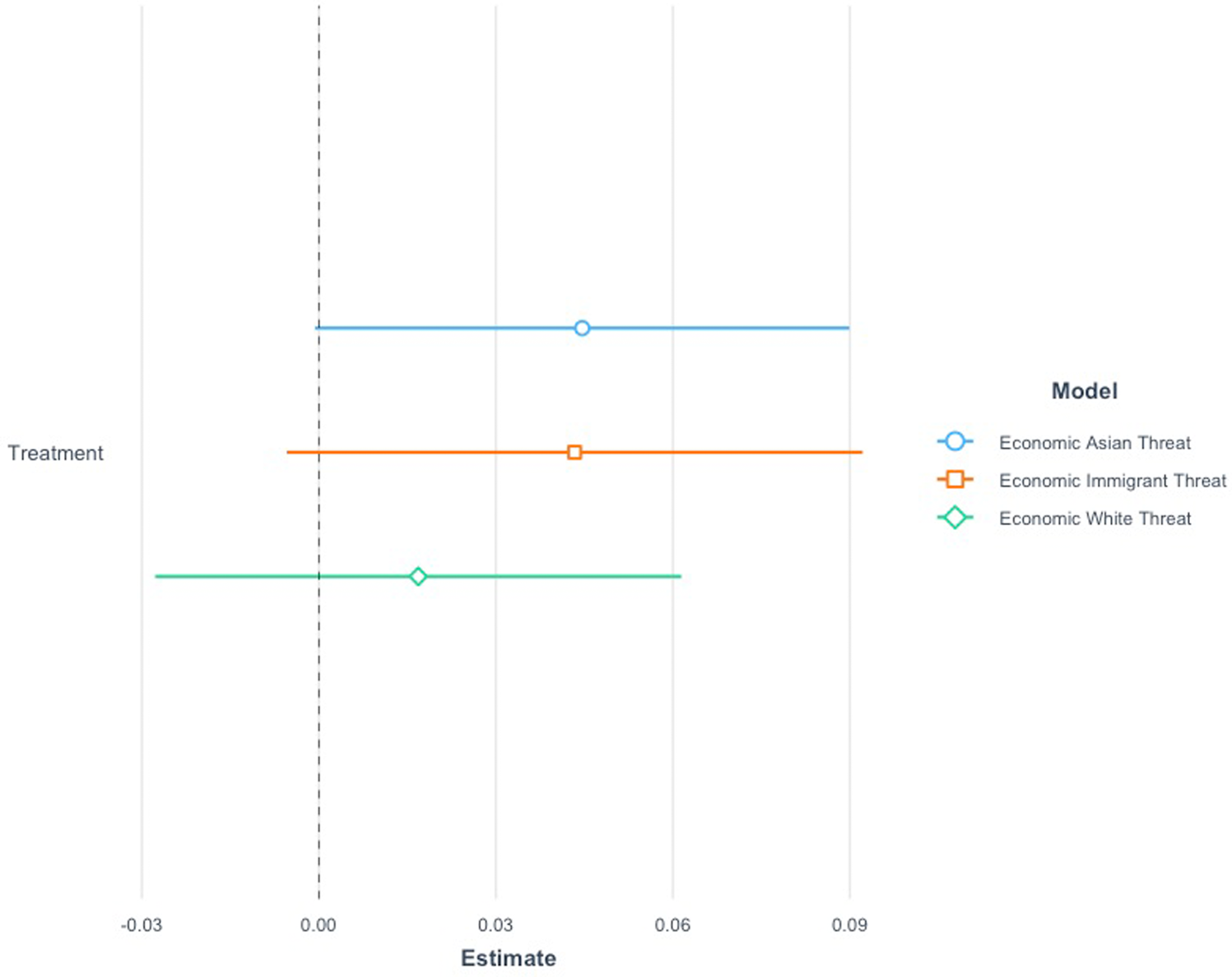

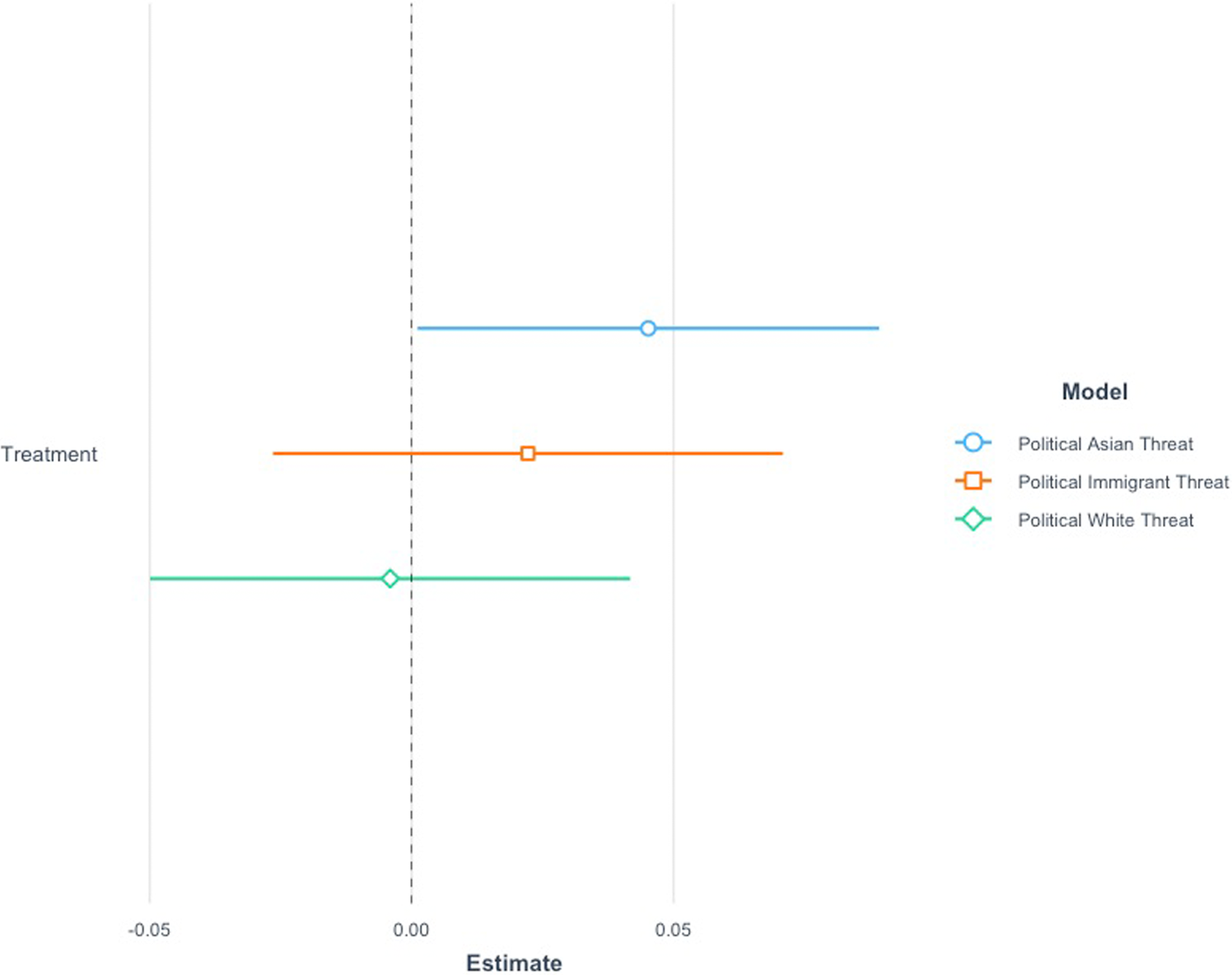

For the following analyses, I use linear regression again to test the effect of the treatment and also include demographic controls. First, in testing for H1b, I find that the threat elicited from the Census information causes a greater sense of threat from Asians specifically across all three types of threat (Figures 4–6). The Census report information about Asians causes a sense of economic threat (p = 0.05), cultural (p = 0.04), and political threat (p = 0.04), all by nearly 5 percentage points.

Figure 4. Cultural threat felt from Asian Americans, immigrants, and white Americans.

Figure 5. Economic threat felt from Asian Americans, immigrants, and white Americans.

Figure 6. Political threat felt from Asian Americans, immigrants, and white Americans.

I confirm H1b across all three of these measures. Increases in threat across all three dimensions indicate robust senses of threat across all three of these dimensions. I find evidence that threat from Asian Americans spills over into perceptions of threat from immigrants, but less consistency relative to Asian Americans.Footnote 7

As a validation check of the other measures, I include senses of economic, cultural, and political from white Americans. Across all three measures, I find insignificant results, which helps to validate that racial threat is coming specifically from Asian Americans. They do not affect feelings of threat that white Americans have from their ingroup, which is expected and gives more support that Asian Americans are generating threat.

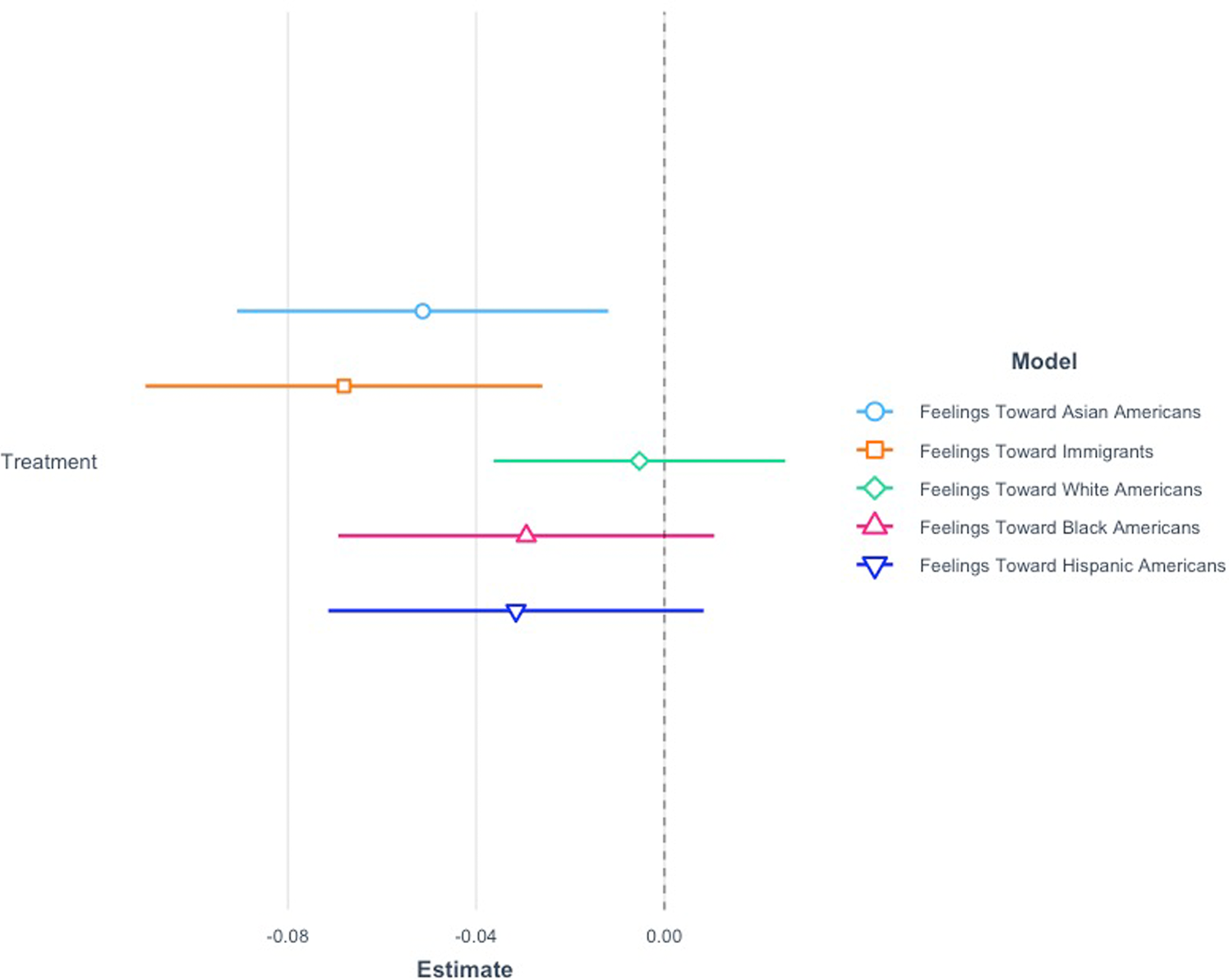

Briefly, I also replicate and extend my test H2. This was the expectation that Asian racial threat would be generalized onto feelings toward immigrants on the whole. To test for this, I again use feeling thermometers and I include additional measures for Hispanic Americans, Black Americans, and white Americans (Figure 7).Footnote 8

Figure 7. Feelings toward Asians, immigrants, whites, blacks, and Hispanics.

I confirm the generalization of threat from Asian Americans (p = 0.01) onto feelings about immigrants (p < 0.01), while also showing its limitation in how it is moved onto attitudes about other racial minority groups. It does not motivate more negative feelings toward Black Americans or Hispanic Americans, thereby reinforcing my presumption that Asian Americans are viewed in a way that is “perpetually foreign.” Next, I turn to retesting how threat alters support ideas of Asian Americans discriminated against in higher education.

10. Replicating Asian racial threat and the Harvard lawsuit

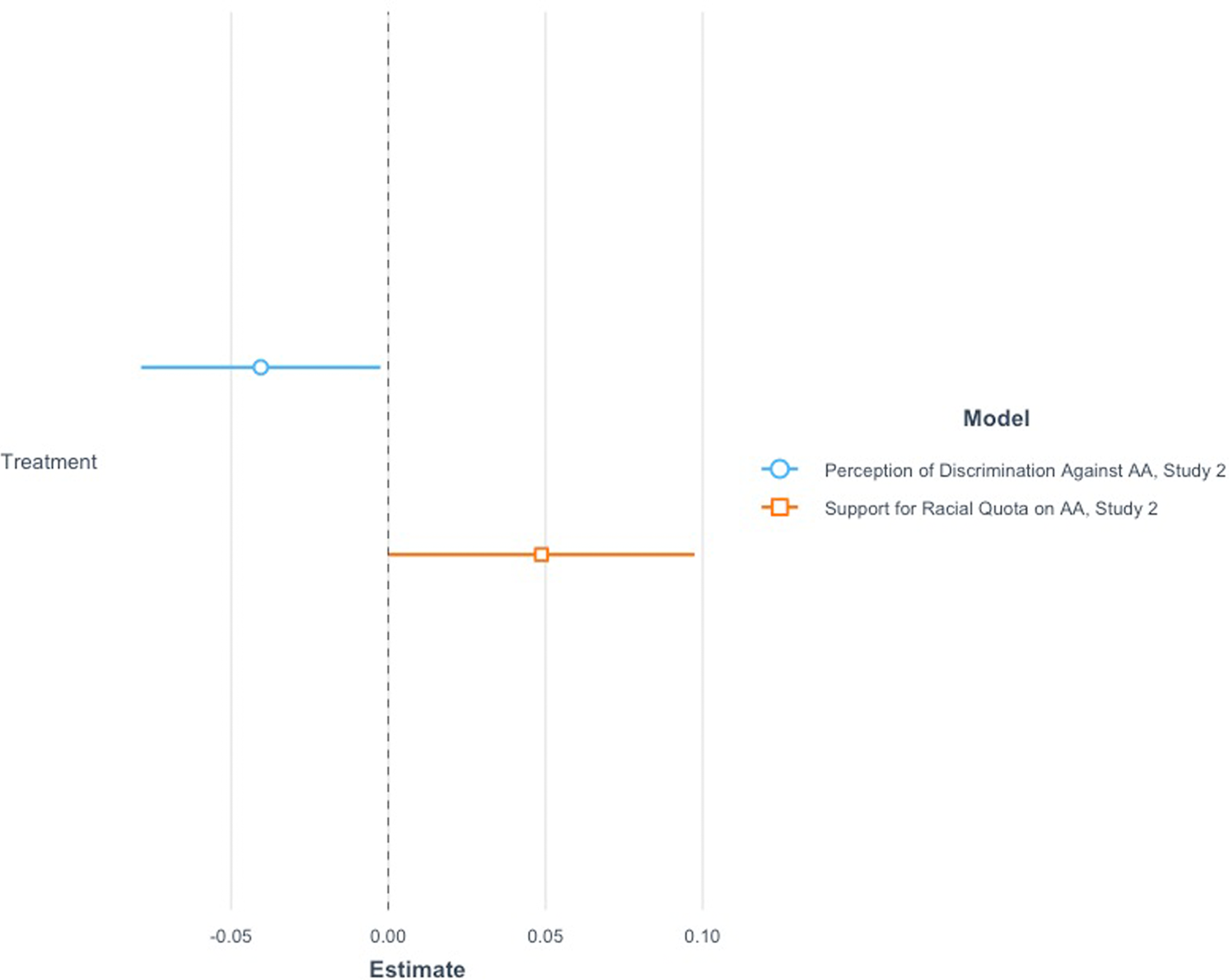

In this second experiment, I replicate the function of threat shifting discriminatory attitudes in higher education and use the same outcome measures that I use in study 1. I expect, as I found in study 1, that the treatment will cause less support for the idea of discrimination against Asians (H3), and more support for the racial quota (H4). This effect of threat on discriminatory attitudes toward Asian Americans is exactly what I find—confirming again H2b in the context of higher education and replicating my results from study 1.Footnote 9

Shown in Figure 8, when white Americans learn of the Census projections about Asians growing in size, they express significantly less support for the idea that Asians are being discriminated against in university admissions (4 percentage point decrease, p = 0.03). This is a second demonstration of threat relaxing ideas of discrimination. Also, in line with my expectations in H4, I find that threat causes white Americans to become more supportive of implementing a racial quota in Asian college admission (5 percentage point increase, p = 0.05). Both of these findings are similar in magnitude to the effects found in study 1.

Figure 8. Effect of Asian racial threat on perceptions of discrimination.

Both of these findings successfully replicate study 1 and show that racial threat does well to both motivate more support for discrimination while decreasing perceptions of it at the same time. Ultimately, this is a robust confirmation of how racial threat shifts views of how Asian Americans are treated in the context of higher education. I find this to be the case even in the midst of changing racial circumstances for Asian Americans because I conducted this study over the span of 2 years with different samples and in different contexts throughout the US.

I also confirm that this concept is more time and context invariant.

A potential caveat to the effect of racial threat on discriminatory attitudes is that I only show this in the case of the Harvard lawsuit. As a check on the portability of the threat in strongly shifting discriminatory attitudes, as well as a test of important contemporary attitudes, I turn finally to testing the role of Asian racial threat in motivating support for discriminatory attitudes in the context of COVID-19.

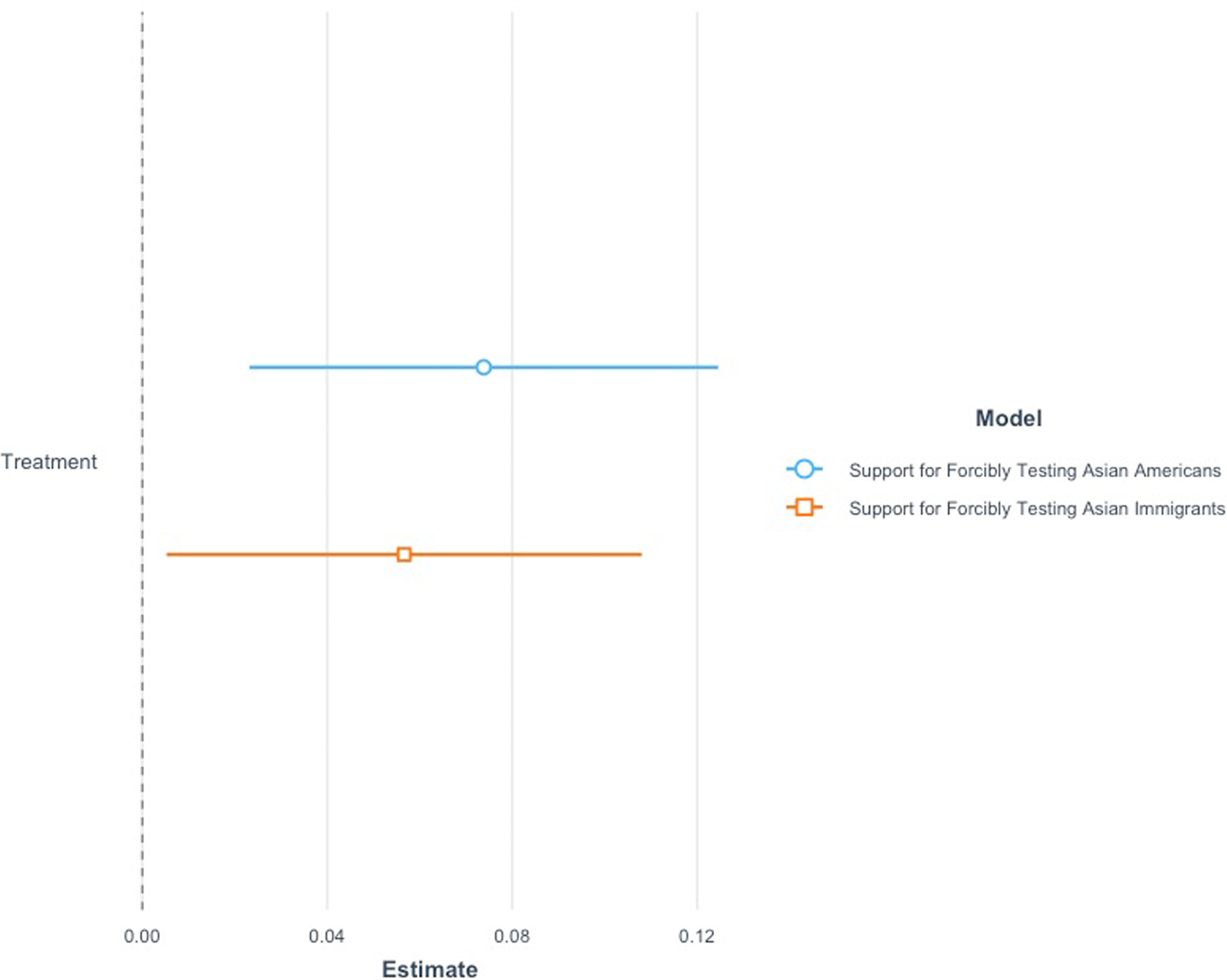

I investigate how threat affects a second set of discriminatory COVID-19 attitudes—specifically, forcibly testing subgroups of Asians for COVID-19. To accomplish this, I look at attitudes on testing Asian Americans and Asian immigrants separately (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Effect of Asian racial threat on support for forcibly testing Asian Americans and Asian immigrants for COVID-19.

Here, I again confirm H4 in another policy context. I show that racial threat from Asians causes more support for specifically discriminating against them within another context. On the first outcome that tests H4, the effect size of racial threat is large, causing white Americans to become 8 percent more supportive of forcibly testing Asian Americans (p = 0.004). I find a similar effect for support for forcibly testing Asian immigrants (6 percent increase in support, p = 0.03). These outcome measures together work as a proof of concept of one another, and the larger idea of Asians viewed as perpetually foreign. Threat from the increasing size in Asians on the whole leads to more discriminatory attitudes about Asian subgroups.

This is yet another confirmation of the idea that racial threat motivates more discriminatory views. Importantly, in contrast with my test of support for discrimination in higher education, the articulation of forcibly testing Asian Americans and immigrants for COVID-19 is more explicit and forceful than a racial quota in college admission. This finding suggests there to be a potential high upper bound on the effect of racial threat on discriminatory views; however, further testing on the full extent that racial threat can motivate discriminatory attitudes is vital for further exposition on this dynamic.

11. Discussion and conclusion

A central implication of this study is that I find effects of threat from Asians to be generalizable to white Americans in the general public. In fact, I find that the Census information on Asians increasing in size is more potent across this representative sample, eliciting threat from Asians across cultural, political, and economic dimensions. The role of racial threat in reducing support for perceptions of discrimination in tandem with an increase in support for discriminatory policy remains after a change in context and over time. This goes to show that my findings from study 1 are not contingent on the salience of the Harvard lawsuit; as the lawsuit was at peak salience when study 1 was fielded. Over 2 years later, I find similar effects of threat on ideas of discrimination in this instance remain—suggesting time invariance of discriminatory attitudes in education.

Another major implication of these findings is that threat from Asian Americans generalizes across related groups. When white Americans feel threat from Asians, they do not identify the threat as only coming from Asian immigrants. I find that when policy that discriminates against both Asian immigrants and Asian Americans, whites do not compartmentalize their discriminatory attitudes, and rather are similarly supportive insofar as they discriminate against Asians generally. This is also further demonstration of the idea that Asian Americans are seen as perpetually foreign.

A final important implication from this study relates to how white Americans become significantly more supportive of targeting Asian Americans as a racial group in the context of COVID-19. The discriminatory nature of the policy proposals should not be understated. The proposals involve not only targeting a specific racial group, but also forcibly testing them. Such a policy would be illegal on a number of grounds, and yet racial threat increases support for it. In comparison to the discussion of Harvard lawsuit case, the COVID-19 measure is overtly discriminatory in its language. This finding works as evidence that, as threat is felt, it can motivate ideas that lead to the erosion of democratic norms, which in this case is the violation of Asian Americans' and Asian immigrants' civil liberties. This finding corroborates recent work that details the connection between racial threat and anti-democratic attitudes (Bartels, Reference Bartels2020). For one, consistent rhetoric about threat could work to erode democratic sentiment among the public. These findings are a demonstration that information about these demographic changes, even without inflammatory rhetoric, can elicit more support for discriminatory policy.

My findings overall present a major problem for a cyclical process of discrimination. Racial threat among white Americans can lead to lessened views of discrimination, yet more support for policies that discriminate. This effect on a nation-wide scale essentially sets a scenario where intergroup conflict would increase as racial demographics change—particularly, as minority racial groups increase in size in the US. Here, I show this in multiple policy realms, but this relationship between threat and discrimination could also apply to behavior toward minority groups. This behavioral question requires further testing and investigation.

The effects of racial demographic change on discriminatory attitudes are consequential for American electoral politics, namely how politics are affected as demographics change. As the US undergoes rapid racial and ethnic changes, racial threat can clearly alter how people think about current politics. If threat is felt from these changes among white Americans, it can motivate an environment where discrimination increases, yet is not seen as increasing in the mass public.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2023.24.

To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TRB3Y5