The power of the presidency is fundamentally dependent upon the actions of bureaucrats. Arguing that presidents direct distributive benefits to preferred constituencies like legislators do, the particularist view of the presidency finds substantial support in the literature (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Burden and Howell2010; Hudak, Reference Hudak2014; Dynes and Huber, Reference Dynes and Huber2015; Kriner and Reeves, Reference Kriner and Reeves2015; Lowande et al., Reference Lowande, Jenkins and Clarke2018). However, extant studies largely overlook the implementation of particularistic policy by providing descriptive accounts of how the bureaucracy might moderate particularism in theory but nonetheless ignoring heterogeneous implementation in empirical analyses either by aggregating spending across all agencies or focusing on outlays from a single agency. Understanding the role of the bureaucracy in implementing presidential policy is integral to characterizing the modern administrative presidency. Regardless of presidential preferences, the effectiveness of presidential policy relies on compliant bureaucrats. The power of the presidency is, after all, the power to persuade (Neustadt, Reference Neustadt1991).

Much of the research on particularism studies the distribution of federal grants and argues that presidents target outlays to co-partisans and other key constituencies. Grants, however, are disbursed by disparate agencies with varying institutional designs, preferences, and incentives (Bertelli and Grose, Reference Bertelli and Grose2009; Arel-Bundock et al., Reference Arel-Bundock, Atkinson and Potter2015; Anderson and Potoski, Reference Anderson and Potoski2016; Berry and Gersen, Reference Berry and Gersen2017; Dahlström et al., Reference Dahlström, Fazekas and Lewis2019). According to the Federal Assistance Award Data System (FAADS), about 200 unique agencies have disbursed grants since 2000. Agencies as different as the US Agency for International Development, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and Department of Education disburse billions of dollars in grants every year with unique processes for drafting calls for applications and adjudicating between potential recipients developed in-house by each agency. This paper takes seriously the diversity of executive agencies responsible for disbursing grants and provides a nuanced account of a posited mechanism of presidential particularism: presidential control of the bureaucracy.

I show that the constellation of agencies responsible for grantmaking varies in its implementation of the president's particularistic preference to target outlays to the president's preferred constituencies. Specifically, this paper interrogates whether ideological alignment with the president and agency politicization condition bureaus’ implementation of particularism benefiting the president. Using data from 21 agencies over 14 years, I test whether agencies vary in their implementation of particularism, and specifically whether ideology and politicization account for such variation.

I find that agencies ideologically proximate to the president engage in particularism while agencies ideologically distant from the president do not. I find no evidence that politicization influences agency implementation of presidential particularism. My findings suggest a more nuanced treatment of presidential particularism that takes seriously the implementation apparatus leveraged by the president to pursue their particularistic goals. Presidents do not have unilateral control over the disbursement of federal funds, even when Congress grants the Executive Branch discretion to allocate money. Instead, the individual agencies responsible for disbursing federal grants constrain the power of the president to target funds to key constituencies.

In the following text, I describe the process by which federal grants are administered, noting the various stages during the allocation process where agencies have broad discretion to disburse grants consistent with their preferences. Then, I test whether bureaucratic agencies implement the president's particularistic goals uniformly and show that only agencies ideologically aligned with the president engage in particularism on the president's behalf. Next, I conduct a placebo test on formula grants over which agencies have little, if any, discretion and show that the bureaucracy does not influence the distribution of formula grants the same way it influences discretionary ones. I conclude with a discussion of the implications of my findings for the theory of presidential particularism, the role of the bureaucracy in the American separation of powers system, and the power of the presidency.

1. The federal grant process

Federal grants come in many forms, but can be lumped into two broad categories: formula and program grants (sometimes called mandatory and discretionary grants, respectively). Formula grants are administered by federal agencies, but the recipients and amounts are determined by Congress. Examples of formula grants include: Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Special Needs Education grants. Program grants, on the contrary, are those for which the federal agencies administering them have discretion over both the recipient and amount based on an often competitive application process developed in-house by the agencies themselves (Kincaid, Reference Kincaid, Haider-Markel, Card, Gaddie, Moncrief and Palmer2008; Chernick, Reference Chernick and Payson2014). Examples of program grants include: National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program grants, Department of Education State Personnel Development grants, and Department of Transportation, Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery grants. Therefore, program grants represent opportunities for discretionary and distributive choices by bureaucrats, whereas formula grants represent the implementation of circumscribed distributive authority from Congress.

The life cycle of a program or discretionary grant consists of four stages: pre-award, award, administration, and post-award. During the pre-award stage, federal agencies develop and publish criteria for evaluating applications while applicants prepare and submit applications. Agencies then evaluate the applications they receive, occasionally using panels of experts to help make decisions. During the award stage, the terms of the grant are established. Then, the agency administers the grant during the administration stage. Finally, during the post-award stage, the agency must comply with reporting requirements to oversight committees, oversight agencies like the Office of Management and Budget or Government Accountability Office, and to databases like the Treasury's online database hosted at usaspending.gov. Once the program has been administered in full, it is closed out and may be audited (Keegan, Reference Keegan2012).

The pre-award stage, where agencies adjudicate among potential recipients, is particularly important. For program grants, no entity but the agency distributing the grant formally makes the decision about where to allocate the outlay. Each agency establishes criteria for applicants and then selects both which applicant will receive the grant from the pool of contenders and how much the grant will be worth. Thus, agencies have discretion over how they will allocate program grants in (1) the development of criteria—which may target certain potential applicants—(2) the selection of recipients—which may favor certain constituencies—and, (3) the determination of the value of the grant—which again may privilege certain partisans. The pre-award stage, then, offers multiple opportunities for agencies to make political and partisan decisions over the allocation of grant outlays: first in the development of criteria, second in the selection of recipients, and last in the valuation of the grant.

Isolating program grants represents a break from extant studies of particularism in grantmaking which tend to pool all grants and then remove programs that do not meet an arbitrary level of within-program variation in funding over time and space.Footnote 1 More importantly, program grants are the appropriate venue for testing whether agencies vary in their implementation of presidential particularism since bureaucrats enjoy broad discretion when deciding how to allocate program grants. Confining the analyses to program or discretionary grants also guards against drawing improper conclusions if, for example, an agency seems to follow its principal's orders if grants are pooled simply because formula grants have been designed such that they benefit certain constituencies independent of the agencies responsible for disbursing them.

2. Expectations

In the following empirical analyses, I test two expectations. First, ideological distance between agencies and presidents should decrease particularistic outlays from an agency. Second, agency politicization should increase particularistic outlays from an agency.

Ideological disagreement with the president should condition an agency's willingness to engage in particularism. If agencies are aligned ideologically with the president, those agencies likely want the president and their party to stay in power and to continue implementing policies consistent with their ideology. Ultimately, presidents’ aims in directing funds to co-partisans are to secure their support, win reelection, strengthen the party brand, and ensure that their party can gain or stay in power in order to implement its platform (Dynes and Huber, Reference Dynes and Huber2015; Kriner and Reeves, Reference Kriner and Reeves2015).

As such, one function of particularism is to cultivate the political capital necessary to enact ideological policy. Although bureaucrats face different incentives than presidents—influence from competing principals (Bertelli and Grose, Reference Bertelli and Grose2009; Gailmard, Reference Gailmard2009; Potter, Reference Potter2019; Potter and Shipan, Reference Potter and Shipan2019), good government or efficiency (Gailmard and Patty, Reference Gailmard and Patty2007; Miller and Whitford, Reference Miller and Whitford2016), ideology (Clinton et al., Reference Clinton, Bertelli, Grose, Lewis and Nixon2012; Potter, Reference Potter2019), and enlarging their budgets (Niskanen, Reference Niskanen1971)—agencies nonetheless care about policy outcomes, particularly in their regulatory spheres, so helping the president direct funds to key constituencies may be mutually beneficial by aiding the reelection campaign of the president and that of their co-partisans. Additionally, since bureaucrats generally desire larger budgets and presidents typically request more in appropriations to agencies with whom they are ideologically aligned (Bolton, Reference Bolton2020), agencies ideologically aligned with the president stand to gain if the incumbent stays in office and can help them do so by directing funds to districts important to their reelection.

Therefore, agencies ideologically aligned with presidents should allocate more funding to presidential co-partisans by implementing the president's particularist agenda. The logic for misaligned agencies is similar. Agencies distant from the president likely are not as invested in the incumbent president's and their party's success in future elections and therefore may not be willing to direct outlays to key constituencies and instead substitute in their own best judgment or standard operating procedures despite the president's preference for particularism. Additionally, agencies ideologically distant from the incumbent president stand to gain from their replacement with a friendlier chief executive who may seek more appropriations for those agencies (Bolton, Reference Bolton2020).

Politicization—the extent to which an agency is filled with political appointees rather than careerists—may also condition an agency's willingness to engage in particularism. How politicization may affect the implementation of particularism is less clear however. Some studies suggest that politicization does result in agency responsiveness to the president since the president is able to stack agencies with loyalists (Berry and Gersen, Reference Berry and Gersen2017; Lowande, Reference Lowande2019), while others suggest the opposite since politicization often reduces bureaucratic capacity so much so that agencies cannot implement their principal's policies even if they want to (Huber and McCarty, Reference Huber and McCarty2004; Huber, Reference Huber2007; Lewis, Reference Lewis2010; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2015). The most straightforward expectation is that by inserting presidential loyalists into agencies, those agencies will be more likely to implement the president's particularist agenda, but reasonable theories predict opposite results.

3. Data and empirical strategy

To test whether the bureaucracy moderates presidential particularism, I compiled an original dataset containing information on discretionary grant outlays from each agency to each congressional district in each Congress from the 106th (1999–2000) to 112th (2011–2012) Congress. I collected data on grants from usaspending.gov which compiles FAADS data at the level of the outlay from each federal agency and reports, among other things, its amount, its recipient's congressional district, and whether it was disbursed pursuant to a program or congressional formula.Footnote 2 The unit of analysis is the agency-congressional district-Congress and each observation represents how much in outlays (in 2018 dollars) each congressional district received from each agency in each Congress. I removed all grants that were allocated based on statutory formulas to isolate only those grants that were subject to agency discretion.

Formula grants, however, offer a nice placebo test. If the results are driven by secular trends in grant disbursement, then we should observe the same results from estimating the same models on formula grants, over which agencies have little, if any, discretion. But if the bureaucracy moderates presidential particularism in the allocation of grants, there should only be a relationship between particularism and agency ideological misalignment with the president or politicization for program grants.

The dataset comprises 21 agencies and over $3.9 trillion in outlays. I aggregate outlays to agencies’ highest organizational level: the department or independent agency (Berry and Gersen, Reference Berry and Gersen2017). The aggregation process resulted in a dataset of 63,075 observations. All agencies but the Department of Homeland Security were in operation throughout the entire period, each of which forms a pair with each of the 435 members of Congress (MC) in each of the seven Congresses (20 × 435 × 7 = 60,900), then the Department of Homeland Security forms a pair with each of the 435 MCs for the five Congresses it was in operation (435 × 5 = 2175), leading to a final dataset of 60,900 + 2175 = 63,075 observations at the agency-district-Congress level.

The dependent variable is the logged outlays (+ 1) in 2018 dollars from each agency to each congressional district in each Congress. The first independent variable of interest is presidential co-partisan which takes the value of one if the MC representing the congressional district receiving the outlay is from the same party as the president in a given Congress, and zero otherwise. To construct the second independent variable of interest, agency–president distance, I take the absolute value of the difference between each agency's Chen and Johnson (Reference Chen and Johnson2015) campaign finance based ideal point estimate and the president's DW-NOMINATE ideal point estimate in each Congress, which are measured on the same scale.Footnote 3 The third independent variable of interest is agency politicization, which I measure as the ratio of political appointees to the number of career senior executive service members following previous study (see, e.g., Lewis Reference Lewis2010; Wood and Lewis Reference Wood and Lewis2017; Lowande Reference Lowande2019). I also include a host of control variables at both the agency- and legislator-levels.Footnote 4

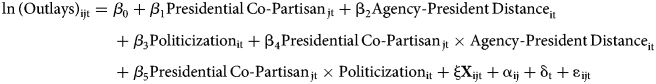

With these data, I then estimate a series of generalized least squares regression models to assess agency implementation of presidential particularism. I estimate variants of the following general model:

where subscript i indexes agencies, subscript j indexes members of Congress, subscript t indexes Congresses, X is a matrix of covariates, $\pmb {\xi }$![]() is a vector of coefficients attending the covariates, $\pmb {\alpha }$

is a vector of coefficients attending the covariates, $\pmb {\alpha }$![]() is a vector of agency-legislator pair fixed effects, and $\pmb {\delta }$

is a vector of agency-legislator pair fixed effects, and $\pmb {\delta }$![]() is a vector of Congress fixed effects. I center each of the continuous independent variables to zero as its mean and standardize them by the standard deviation of their residualized values after absorbing variation from agency-legislator and Congress fixed effects (Mummolo and Peterson, Reference Mummolo and Peterson2019), thus coefficients should be interpreted as the change in logged outlays given a standard, within-agency increase in the independent variables.

is a vector of Congress fixed effects. I center each of the continuous independent variables to zero as its mean and standardize them by the standard deviation of their residualized values after absorbing variation from agency-legislator and Congress fixed effects (Mummolo and Peterson, Reference Mummolo and Peterson2019), thus coefficients should be interpreted as the change in logged outlays given a standard, within-agency increase in the independent variables.

Formally, if agencies ideologically distant from the president implement particularistic policy less vigorously than those ideologically proximate, we would expect β2 + β4 < 0 (i.e., increasing ideological distance decreases outlays to presidential co-partisans) and β2 > 0 (i.e., increasing ideological distance increases outlay to presidential contra-partisans), which implies β4 < 0. If more politicized agencies implement particularistic policy less vigorously than non-politicized one, we would expect β3 + β5 > 0 (i.e., increasing politicization increases outlays to presidential co-partisans) and β3 < 0 (i.e., increasing politicization decreases outlays to presidential co-partisans), which implies β5 > 0.

The agency-legislator fixed effects adjust for any time-invariant characteristics that may affect the distribution of federal grants including, but not limited to, agency structure and independence (Selin, Reference Selin2015),Footnote 5 workforce skill (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Clinton and Lewis2018), legislator district, legislator gender (Anzia and Berry, Reference Anzia and Berry2011), and the unobservable aspects of the relationship between each legislator and each agency. The Congress fixed effects adjust for any common shocks experienced by all agencies such as the president's party (Reingewertz and Baskaran, Reference Reingewertz and Baskaran2019), the majority party in the House of Representatives, and national economic health. This dual fixed effects design allows for identification from within-agency-legislator variation in the key independent variables. Identification comes from the same representative changing from presidential co-partisan to presidential contra-partisan or vice versa, and changes in the ideological distance between the same agency and the president over time.

4. Results

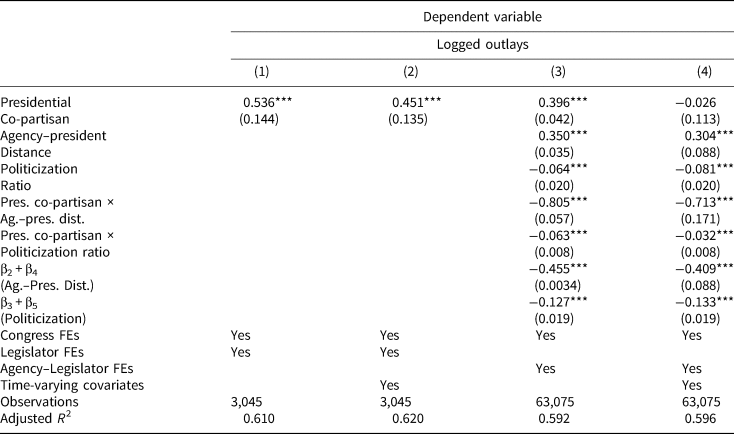

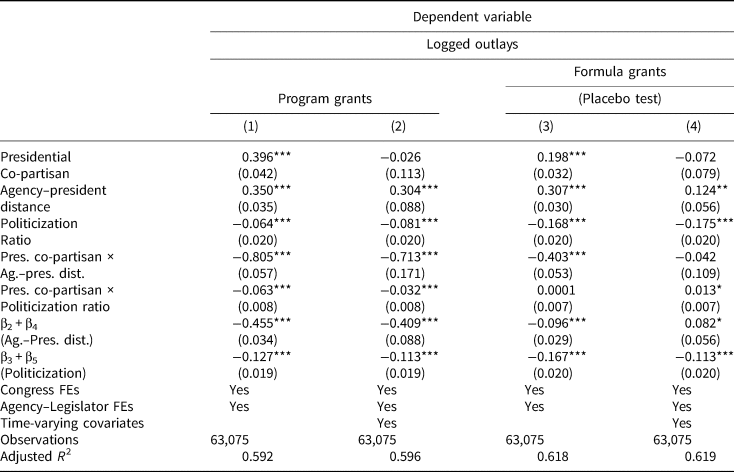

Table 1 reports the parameters estimated from the model in Equation 1.Footnote 6 First, I report the aggregate level of particularism in the sample by aggregating the data to the legislator-Congress level. The coefficients on presidential co-partisan in models 1 and 2 indicate that, on average, congressional districts represented by legislators who share the president's party receive more in outlays.

This estimate is consistent with prior research on grants and particularism and indicates that my sample of agencies, on average, displays particularism (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Burden and Howell2010; Hudak, Reference Hudak2014; Dynes and Huber, Reference Dynes and Huber2015; Kriner and Reeves, Reference Kriner and Reeves2015).

Table 1. Agency ideology, politicization, and presidential particularism

*p< 0.1; **p< 0.05; ***p< 0.01

Note: Unit of analysis for models 1 and 2 is the district-Congress and for models 3 and 4 is the agency-district-Congress. Heteroskedasticity-corrected errors clustered by legislator (models 1 and 2) and agency-legislator (models 3 and 4) reported in parentheses. Model 2 controls for whether each member of Congress in each Congress is in the majority party, sits on the appropriations committee, sits on the ways and means committee, whether each member of Congress won their previous election with a margin less than 0.05, each district's logged population and logged median income, and model 4 additionally controls for the distance between each agency's Chen and Johnson (Reference Chen and Johnson2015) ideal point estimate and each member's DW-NOMINATE ideal point estimate.

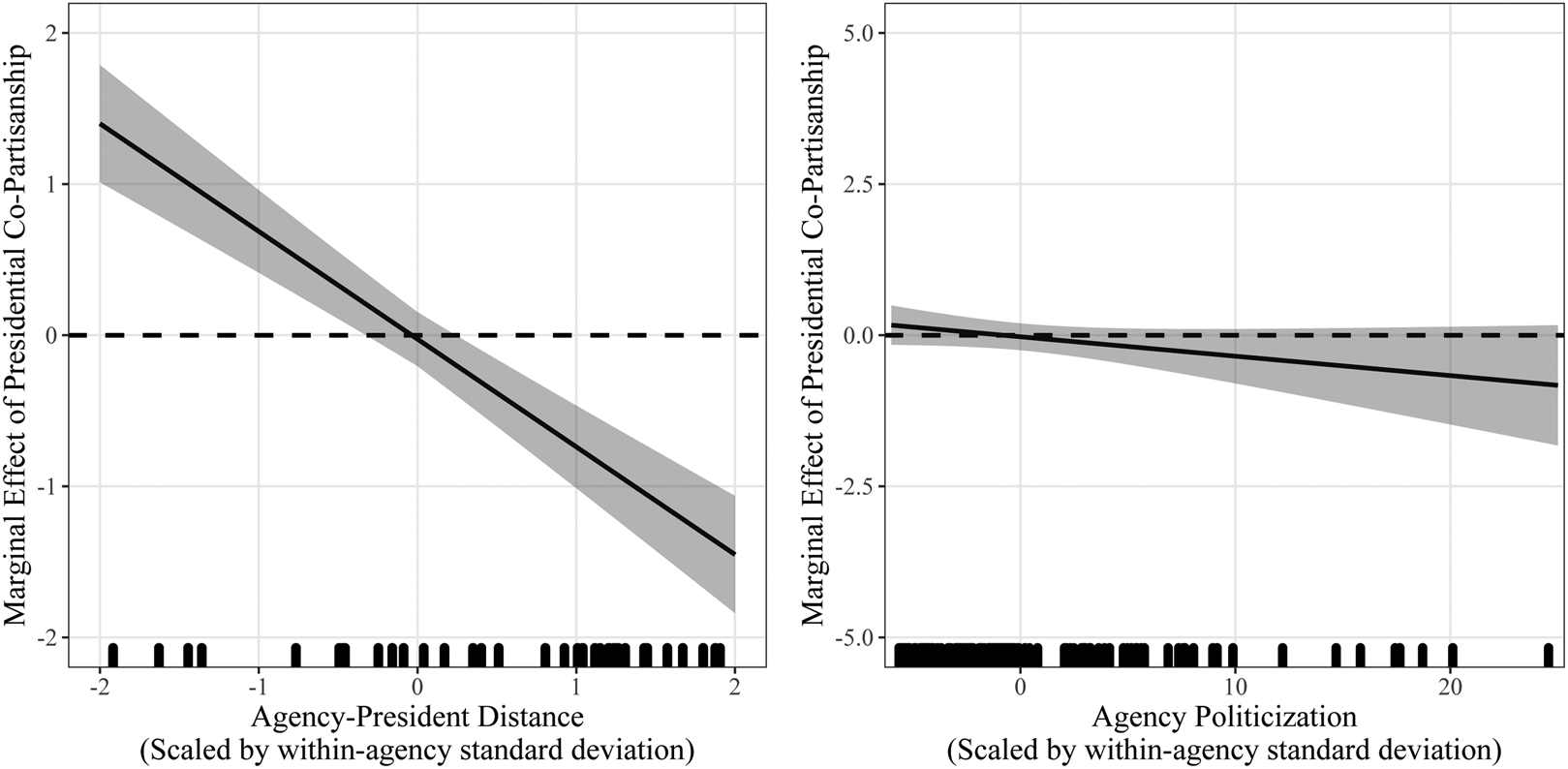

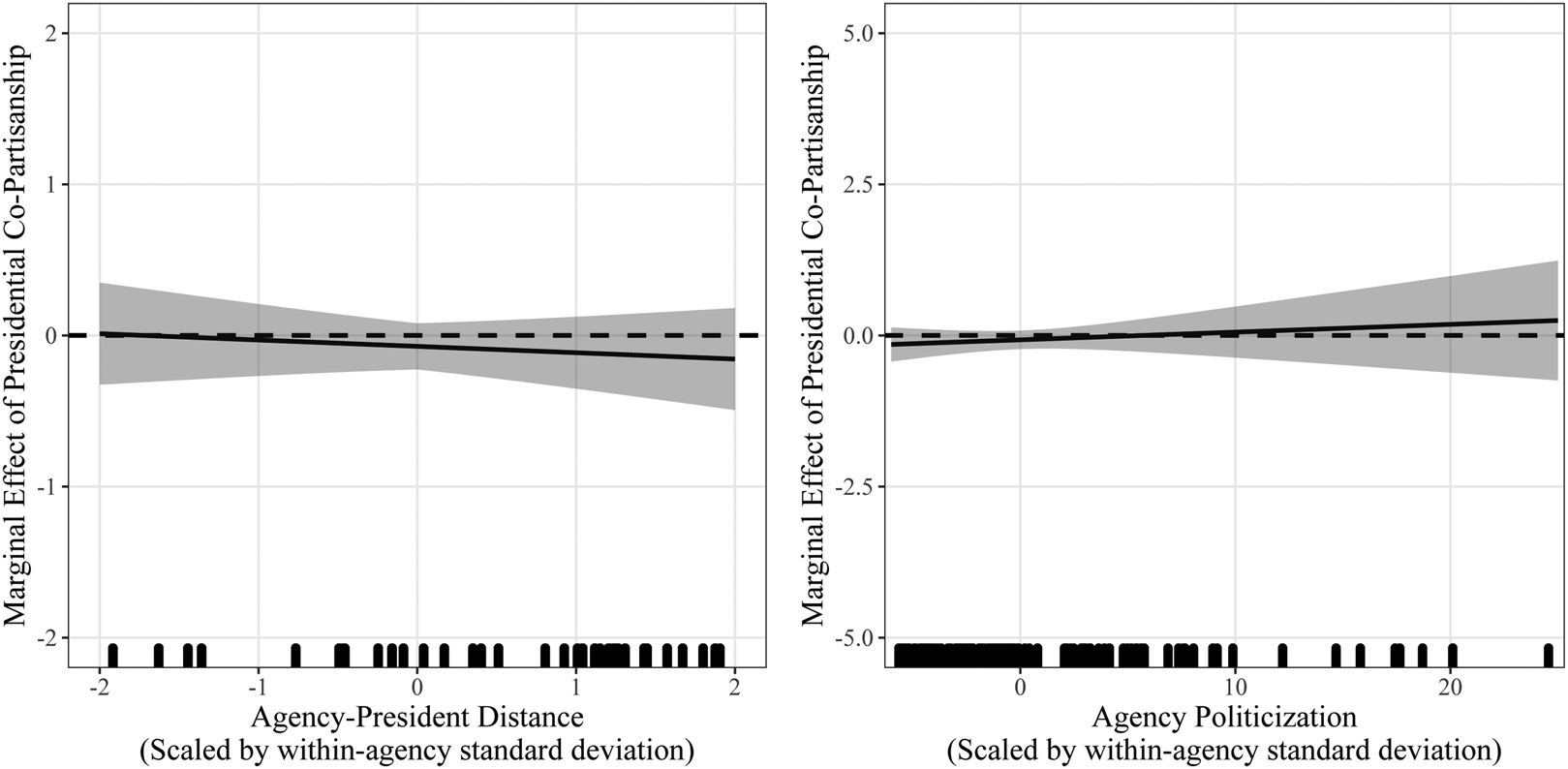

Models 3 and 4 disaggregate the data to the agency-district-Congress level and show that particularism is primarily implemented by agencies ideologically proximate to the president. Figure 1 displays the marginal effect of presidential co-partisanship on outlays at different levels of agency–president distance and politicization derived from model 4 in Table 1. Agencies ideologically proximate to the president allocate more to presidential co-partisans than contra-partisans. Ideologically distant agencies, on the contrary, allocate the same or less in outlays to districts represented by presidential co-partisans.

Fig. 1. Particularism by agency–president distance and politicization. The figure is derived from model 4 in Table 1. Left panel displays the marginal effect of presidential co-partisan at all observed levels of agency–president distance and right panel displays the marginal effect of presidential co-partisan at all observed levels of agency politicization. The rug along the x-axis displays the densities of the respective variables.

The results provide no evidence that politicization influences agency implementation of presidential particularism since the marginal effect of presidential co-partisanship does not vary across different levels of agency politicization. Although the coefficient on politicization is negative, indicating that presidential contra-partisans receive less in outlays as agencies become more politicized, the sum of β3 and β5 is also negative, indicating that presidential contra-partisans also receive less in outlays as agencies become more politicized. Furthermore, the effect sizes are quite small. A standard, within-agency increase in politicization reduces outlays to co-partisans by about 12 percent and to contra-partisans by about 7.8 percent. If anything, more politicized agencies allocate more funding to contra-partisans than co-partisans, but not by much. Ideological distance between agencies and presidents on the other hand has a much more pronounced effect. A standard, within-agency increase in agency–president distance increases outlays to contra-partisans by about 35 percent and decreases outlays to co-partisans by about 34 percent.

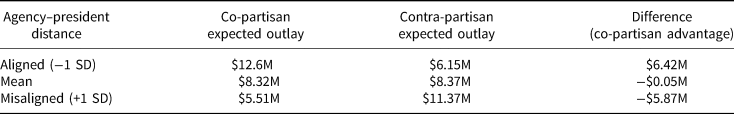

Table 2 reports expected outlays for co- and contra-partisans, and the difference between the two, at different levels of agency–president distance.Footnote 7 An agency one within-agency standard deviation below the mean of agency–president distance allocates, on average, $6.4 million more in funding to presidential co-partisans, while an agency one within-agency standard deviation above the mean allocates, on average, $5.9 million less over the course of an average two-year congressional session.

Table 2. Substantive effects, agency–president distance

Note: Expected values calculated with estimates from model 4 in Table 1 holding continuous variables at their means, binary variables at their modes, and adjusting for the estimated, median intercept of the agency-legislator fixed effects. Standard deviations measured as the standard deviation of the residualized values of agency–president distance with respect to agency-legislator and Congress fixed effects following Mummolo and Peterson (Reference Mummolo and Peterson2019).

4.1 Placebo test with formula grants

In the main analysis above, I report results only from program grants over which agencies have much discretion. If the results are driven by secular trends in grant disbursement rather than bureaucratic discretion, we should observe the same results from estimating the same model on formula grants over which agencies have little, if any, discretion. For the main analysis to pass the placebo test, it must be the case that the marginal effect of presidential co-partisan does not vary with agency–president distance.Footnote 8

In other words, it must be the case that particularism, or the advantage to presidential co-partisans, does not vary with the ideological alignment between the president and the disbursing agency.

Formally, to pass the placebo test, it must be that $\beta _4^{\rm Placebo}< \beta _4^{\rm Main}$![]() or, more conservatively, that $\beta _4^{\rm Placebo} \leq 0$

or, more conservatively, that $\beta _4^{\rm Placebo} \leq 0$![]() . Table 3 reproduces the main analysis in models 1 and 2 and reports the parameters estimated for the placebo model on formula grants in models 3 and 4. For the placebo model without covariates, the effect ($\beta _4^{\rm Placebo}$

. Table 3 reproduces the main analysis in models 1 and 2 and reports the parameters estimated for the placebo model on formula grants in models 3 and 4. For the placebo model without covariates, the effect ($\beta _4^{\rm Placebo}$![]() ) is only about half of the effect in the main model, passing the weaker placebo test. More importantly, once including covariates, the effect disappears and is null (p ≈ 0.35), passing the more conservative test. The weak politicization findings for program grants are replicated for formula grants, so I cannot rule out that secular trends in grant disbursement, and not bureaucratic discretion, account for the politicization results in Table 1. I can rule out that secular trends account for the ideology findings however.

) is only about half of the effect in the main model, passing the weaker placebo test. More importantly, once including covariates, the effect disappears and is null (p ≈ 0.35), passing the more conservative test. The weak politicization findings for program grants are replicated for formula grants, so I cannot rule out that secular trends in grant disbursement, and not bureaucratic discretion, account for the politicization results in Table 1. I can rule out that secular trends account for the ideology findings however.

Table 3. Placebo test with formula grants

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

Note: Unit of analysis is the agency-district-Congress. Heteroskedasticity-corrected errors clustered by agency-legislator reported in parentheses. Models 2 and 4 control for whether each member of Congress in each Congress is in the majority party, sits on the appropriations committee, sits on the ways and means committee, whether each member of Congress won their previous election with a margin less than 0.05, each district's logged population and logged median income, and for each agency's politicization ratio for each Congress, and the distance between each agency's Chen and Johnson (Reference Chen and Johnson2015) ideal point estimate and each member's DW-NOMINATE ideal point estimate.

The main analysis of ideological distance on program grants passes the placebo test, indicating that ideological dissimilarity between agencies and presidents only affects the distribution of federal grants when the agencies responsible for administering those grants have discretion over their distribution. When agencies do not have discretion, as with formula grants written by Congress, policy disagreement among presidents and agencies has no effect on whether agencies reward presidential co-partisans with federal funds. To see the difference more clearly, Figure 2 displays the marginal effect of presidential co-partisan for formula grants, over which agencies have little discretion. The slope is almost exactly zero, unlike for program grants in the main analysis in Figure 1.

Fig. 2. Placebo test: particularism in formula grants. The figure is derived from model 4 in Table 3. The rug along the x-axis displays the density of each variable.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, I have shown that executive agencies do not uniformly implement the president's particularistic policy preferences. Only agencies ideologically proximate to the president allocate more in grant funding to presidential co-partisans. Ideologically distant agencies do not engage in particularism. Critically, the bureaucracy only moderates presidential particularism when disbursing program grants, over which agencies have discretion to create application criteria, select recipients, and choose the value of the grant. When disbursing formula grants written by Congress, bureaucratic ideology has no effect on presidential particularism.

The findings presented here suggest a more nuanced treatment of presidential particularism, taking seriously the implementation apparatus with which presidents must contend in order to pursue their particularistic goals. The power of the presidency is the power to persuade (Neustadt, Reference Neustadt1991), and conclusions about presidential power that rely on the president's ability to direct benefits to their preferred constituents must take into account that presidents have not persuaded and cannot persuade every agency in the bureaucracy to implement their particularistic goals. Agencies do not implement policy blindly, nor do they acquiesce in every order from the president. Rather, federal agencies are active players in the contestation and formulation of public policy and a critical part of the checks on presidential power and balances between institutions in the American political system (Miller and Whitford, Reference Miller and Whitford2016).

This paper complements a growing body of literature on presidential power that interrogates the agency problems inherent in the pursuit of presidential policy preferences. Regardless of presidential preferences, the effectiveness of presidential policy relies on compliant bureaucrats (see Lowande and Rogowski Reference Lowande and Rogowski2020 for an overview). Even for the hallmark of unilateral action, the executive order, presidential policy directives are not self-enforcing (Rudalevige, Reference Rudalevige2012; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2015). This paper has shown that presidential power to funnel benefits to key constituencies also is not self-enforcing. Only agencies aligned with the president implement the president's particularistic agenda.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.29