Partisanship is a key variable in political behavior research (Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002; Dalton and Weldon, Reference Dalton and Weldon2007; Brader and Tucker, Reference Brader and Tucker2009; Brader et al., Reference Brader, Tucker and Duell2013). In the US two-party system, an increasing number of scholars conceptualize partisanship as a social identity (Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002; Mason, Reference Mason2015) that motivates partisan loyalty and defensive partisan reasoning even in the face of weak party leadership or poor policy performance. Yet, in European multi-party systems, questions remain regarding the significance and durability of party attachments (Thomassen, Reference Thomassen, Budge, Crewe and Farlie1976; Dalton and Wattenberg, Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2002; Johnston, Reference Johnston2006; Thomassen and Rosema, Reference Thomassen and Rosema2009), and secondarily whether it can be considered a social identity as in the US.

It has been difficult to fully test the political effects of partisanship in Europe for two reasons. First, European election studies typically include batteries of questions on ideology, policy views, and assessments of party performance but rarely include an adequate measure of expressive partisanship, a more recent concept that views partisanship as a social identity (see Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018). That means a key facet of partisanship has been inadequately measured in election studies. Second, many election studies collect data around the time of an election, making it difficult to empirically separate the effects of partisanship from that of vote choice. It is especially fruitful to examine the effects of expressive partisanship over time in national contexts experiencing change in parties, their leadership, or social and economic conditions to disentangle the effects of partisanship from vote preference.

We address these difficulties in two ways: First, we rely on panel data to measure partisan loyalties a full two years before the election to establish the causal effect of expressive partisanship on vote choice. Panel data provide a far better test of the enduring effects of partisanship than cross-sectional data in which partisanship and vote choice are highly endogenous. Second, we utilize a multi-item scale to measure partisan identity. This scale has been shown to be a better predictor of political behavior in the UK, the Netherlands, and Sweden than the standard partisan strength item (see Bankert et al., Reference Bankert, Huddy and Rosema2017). Here, we focus on political behavior in Italy over the course of the 2013 national elections, a volatile political time period marked by weakened support for mainstream political parties—a phenomenon referred to as dealignment—as well as the unexpected gains of the anti-establishment party, namely the Five Star Movement (MoVimento 5 Stelle, M5S), and its leader Beppe Grillo. This tumultuous time in the Italian party system represents an especially hard test of the durability and impact of partisanship.

We find that expressive partisanship predicts in-party vote over time while reducing support for the emergent M5S, suggesting that it contributes to political stability in Italy during a time of unprecedented economic and political crisis. Our results thus underscore the importance of partisanship to system stability and its role as a source of resistance to anti-establishment parties such as M5S, albeit in a country with low standing levels of partisan attachments. We also find that non-partisans—especially the best-educated—are more likely than partisans to support M5S. This finding resonates with Dalton's (Reference Dalton1996, Reference Dalton2014) argument that the best-educated voters are most open to new political parties.

Overall, the results of this study document the resilience of partisanship and its importance in stabilizing multi-party systems, even in turbulent times. In the remainder of this manuscript, we review prior scholarship on expressive partisanship, which informs our hypotheses and measurement strategy. We then introduce the data—a nationally representative panel of Italian voters—and present our analyses and results. We conclude with implications for the normative evaluation of partisanship and its role in dynamic political systems.

1. Expressive model of partisanship

To best assess the political effects of partisanship in Europe, it is important to gauge its full effects and measure it adequately. In prior scholarship, partisanship is thought to reflect agreement with the in-party's policy stances and is responsive to the quality of the party's leadership as well as its performance in government. In this traditional model of partisanship, it is assumed that voters can map their preferences onto the in-party's policy agendas and performances. To test the validity of this instrumental conceptualization of partisanship, researchers have examined the link between partisanship and leader evaluations, ideological and issue proximity (Dalton and Weldon, Reference Dalton and Weldon2007; Garzia, Reference Garzia2013)—the latter are factors to which partisanship should respond when it is grounded in instrumental concerns. Indeed, Garzia (Reference Garzia2013) demonstrates that partisanship in several European multi-party systems is linked to party leader evaluations.

Identity-based expressive models of partisanship present a powerful alternative approach to partisanship. In the expressive model of partisanship, partisanship is a social identity—a subjective sense of belonging to a group—that remains stable even as party platforms, party leaders, and their performances in government change (Mason, Reference Mason2015; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021). In contrast to the instrumental model, partisan identity motivates the defense of the party even in the face of negative information and generates strong action-oriented emotions that result in political action on behalf of the in-party to protect and advance the party's status and electoral dominance. Notably, these identity-driven processes minimize partisans' responsiveness to poor party leadership or altered policy platforms, leading to relatively stable partisan loyalties (Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002). This expressive model of partisanship is based on social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979), a well-established theoretical framework in the study of intergroup relations. The motivation to protect and advance the group's status is a cornerstone of the social identity approach and the psychological foundation for the development of in-group bias. Defensive motivation and group support increase with identity strength, leading to the prediction that the strongest partisans will work most actively to increase their party's status, including electoral victory (Ethier and Deaux, Reference Ethier and Deaux1994; Fowler and Kam, Reference Fowler and Kam2007; Andreychik and Gill, Reference Andreychik and Gill2009).

This psychological conceptualization of partisanship led to the development of a new survey instrument that measures partisan identity using a multi-item scale adapted from Mael and Tetrick's (Reference Mael and Tetrick1992) Identification with a Psychological Group scale. This new scale has been empirically validated in the US two-party context (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018) as well as in European multi-party systems (Bankert et al., Reference Bankert, Huddy and Rosema2017). The scale contains items such as “When I speak about this party, I say ‘we’ instead of ‘they’” or “I am interested in what other people think about this party”. These scale items avoid references to ideology or issue preferences and instead gauge a subjective sense of belonging to the party and its group of supporters. The scale yields a fine-grained continuum of partisan identity strength that allows us to test the effect of weak and strong expressive partisanship.

2. Partisanship in a volatile party system

A volatile party system, widespread corruption that reduces system trust, or ineffective leadership can encourage the emergence of anti-system political parties that destabilize the existing political landscape (Bustikova, Reference Bustikova2009; Rico et al., Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017; Bosch and Durán, Reference Bosch and Durán2019). Traditionally, multi-party systems have been particularly vulnerable to the emergence of anti-establishment parties because parties come and go at a much faster rate than in two-party systems. This volatile party environment can disrupt the development of strong party ties by encouraging voters to switch parties or abandon partisan allegiances, especially in times of social, political, or economic change (Converse and Dupeux, Reference Converse and Dupeux1962; Schickler and Green, Reference Schickler and Green1997).

Such electoral volatility can often be traced to unresponsive mainstream parties that allow anti-establishment parties to establish ownership over salient issues such as immigration that may have been ignored by the mainstream parties (Mair, Reference Mair2013; Golder, Reference Golder2016). Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006) argue that by ignoring voters' concerns about recent economic, cultural, and social changes, traditional parties create fertile ground for anti-elite parties that destabilize the party system. As Golder (Reference Golder2016) and others (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1988, Reference Kitschelt1997; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005) point out, traditional political parties have often responded slowly to changes in underlying societal cleavages, leaving room for the emergence of far-left and far-right parties. Pervasive corruption can also destabilize the political party system by pushing voters away from mainstream parties and increasing support for insurgent anti-establishment parties (Orriols and Cordero, Reference Orriols and Cordero2016).

This leads to the inference that a system characterized by poorly performing political parties, a volatile partisan landscape, or pervasive economic and political crises will exhibit weakened loyalties to mainstream political parties—consistent with the dealignment hypothesis. There is suggestive aggregate-level evidence in support of the dealignment hypothesis. Partisan dealignment generated political volatility in France during the early days of the Fifth Republic in the early 1960s, a period characterized by considerable political change (Converse and Dupeux, Reference Converse and Dupeux1962; Converse and Pierce, Reference Converse and Pierce1986). Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Tavits and Homola2014) examined aggregate levels of party support and found that lower levels of attachment to mainstream parties in established democracies increased support for anti-establishment parties in 31 established and newly post-communist democracies between 1996 and 2007. Norris (Reference Norris2005), drawing on several case studies, notes that countries with weaker attachment to mainstream center-left and center-right parties exhibit greater electoral volatility, providing an opening for anti-establishment parties that defy the traditional left-right distinction.

Aggregate-level data are useful in showing how levels of partisanship within a nation affect trends in party support. But aggregate data make it difficult to know how partisanship responds to destabilizing political and economic crises among individual citizens. Indeed, one can show that systemic factors such as an unstable political system could result in low levels of partisanship and successful anti-establishment parties without providing clear evidence that weak or non-partisans drive support for an anti-establishment party. To investigate the influence of partisanship on support for anti-system parties among individuals, we believe it is important to trace the effects of partisanship over time using panel data. By doing so, we can show whether strong prior partisan attachments maintain the stability of the party system even amid crisis. Yet, there have been surprisingly few empirical tests of this hypothesis at the individual level.

There is some prior evidence that system instability is linked to non-partisanship at the individual level: Dassonneville and Hooghe (Reference Dassonneville and Hooghe2018) use individual-level survey data to examine the effects of partisanship on political alienation. The authors distinguish between two possible effects of non-partisanship: openness to new political ideas and parties or alienation from all parties (Rose and McAllister, Reference Rose and McAllister1986). They analyze data from western European nations included in the European Election Studies surveys (1989–2014) and find that non-partisans are especially alienated (measured as a low likelihood of voting for the party to which they are closest)—a factor likely to boost support for anti-establishment parties, thereby exacerbating electoral volatility. Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser (Reference Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser2019) dig further into the connection between partisan alienation and populism in Chile. They find a strong link between populism and hostility toward both center-left and center-right party coalitions among non-partisans in Chile (analogous to political alienation).

The flip side of this process—the capacity of strong identification with a mainstream party to inhibit support for anti-establishment forces—has received virtually no research attention. Recent analyses of support for right-wing populist parties at the individual level have rarely included a measure of partisanship, let alone partisan identity, to test this hypothesis directly. Indeed, prior scholarship on the individual determinants of support for anti-establishment parties has documented greater support for them among the less well-educated and those low in political trust (Hooghe and Oser, Reference Hooghe and Oser2015), but the effect of party identification has remained unexplored. We address this omission in the current study by utilizing a multi-item measure of partisan identity in Italy. We find that individuals who score highly on this partisan identity scale are the least susceptible to the appeal of M5S. Notably, our argument focuses on anti-establishment parties in particular, rather than general electoral volatility. While some prior scholarship has demonstrated a link between partisanship and stable electoral outcomes (e.g., see Lupu and Stokes (Reference Lupu and Stokes2010) for a study of new democracies over time), we consider support for anti-establishment parties a particular form of electoral volatility that is associated with the erosion of liberal democratic norms and institutions across many democracies in Europe and beyond (Juon & Bochsler, Reference Juon and Bochsler2020; Haggard & Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2021). Given these drastic consequences for the quality of democratic systems, a targeted analysis of support for anti-establishment appears warranted to us.

3. Non-partisans and the role of education

While we focus on the role of partisanship in shaping support for anti-establishment parties, there is also a lively debate surrounding their appeal among non-partisans. Indeed, there is some dispute over whether non-partisans are simply apolitical and indifferent to any political party or especially drawn to anti-establishment parties. Given our focus on party system instability introduced by an anti-establishment party, it is important to consider this debate.

Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser's (Reference Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser2019) Chilean data suggest that non-partisans are a heterogeneous group; some are politically indifferent, have no party preferences, and no affinity for anti-establishment parties (i.e., apartisan). Others dislike one or both major left-right party coalitions and are attracted to anti-establishment ideals (i.e., anti-partisan). In the Chilean data, education levels help to differentiate apartisan and anti-partisans, whereby the less well educated are more likely to be apartisans who lack any positive or negative feelings about the parties and reject populism while the best-educated are more likely to be anti-partisan and thus more susceptible to the anti-establishment appeal. This insight aligns with Dalton and Wattenberg's (Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2002) claim that politically sophisticated and better-educated voters are “the new non-partisans who remain interested in the political process, but who are more likely to think of democratic politics in apartisan or even anti-partisan terms” (p. 263).Footnote 1 These findings thus underscore the importance of drawing distinctions among non-partisans based on their level of educational attainment when examining support for anti-establishment parties. In alignment with Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser's findings (Reference Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser2019), we expect that the best-educated non-partisans may be more susceptible than less well-educated non-partisans to anti-establishment political parties such as M5S. This prediction is also consistent with Zaller's (Reference Zaller1992) model of elite influence in which sophisticated voters with the most political information can best map their beliefs onto a new political party. This novel expectation has yet to be tested.

4. Study context: Italian party politics 2011–2013

We advance research on the role of expressive partisanship in Italy by examining individual-level panel data collected over the course of the 2013 election, a volatile period capturing considerable partisan change. Italy is a tough case in which to test the resiliency of partisanship because it is a dynamic multi-party system in which there has been considerable change in both political parties and leaders over the last decade. During this period, the country has experienced economic instability, a factor that may facilitate support for an anti-establishment party (Cachafeiro and Plaza-Colodro, Reference Cachafeiro and Plaza-Colodro2018). In the following, we provide a brief description of Italian politics to illustrate this point and place our analyses in context.

The Italian party system has shown considerable volatility since the 1950s but is nonetheless anchored by a traditional left-right party axis (Bellucci, Reference Bellucci2014). This traditional axis was challenged in the lead-up to the 2013 national election, a period characterized by considerable political change. During this time, the country had three prime ministers, went through its worst recession since 1929, and lived under harsh austerity measures that barely avoided national bankruptcy leading to a sharp decline in trust in the party system and political institutions (see Figure A1). During this period, a powerful new anti-establishment force emerged: the M5S, founded in 2009 by Genovese comedian Beppe Grillo. M5S gained ground among Italian voters using a mix of anti-establishment, anti-EU, and anti-immigration rhetoric (Passarelli and Tuorto, Reference Passarelli and Tuorto2018). Grillo's party gained a place on the general election ballot in 2013 by catalyzing the disillusionment and emergent Euroskepticism of Italian voters (Bordignon and Ceccarini, Reference Bordignon and Ceccarini2015; Franchino and Negri, Reference Franchino and Negri2018).

The M5S posed a challenge to the traditional left-right axis, which had dominated the Italian party system since the end of WWII. The Communist Party and its successors combined with more moderate socialists and Christian Democrats had shaped the Italian left for decades (Pasquino, Reference Pasquino2003). In more recent years, Silvio Berlusconi and his party forged a center-right coalition made up of nationalists, northern Italian separatists, and moderate Catholic right-wing voters that promoted a free-market economic message (Sassoon, Reference Sassoon2014). Until 2013, the major Italian political parties had thus been divided along a traditional left-right axis in which partisanship and ideological convictions were largely aligned.

The entrance of Grillo's M5S upended this left-right party axis. As noted by Pirro and van Kessel (Reference Pirro and van Kessel2018), the movement “…defies straightforward categorizations in terms of left and right” (p. 329), drawing support from both sides of the ideological spectrum.Footnote 2 This assessment is consistent with Grillo's own description of his political party: “The days of ideology are over. The 5 Stars Movement is not fascist; it is neither right nor left. It is above and beyond” (Grillo, Reference Grillo2013). Indeed, prior scholarship on the political preferences of M5S supporters revealed greater ideological heterogeneity than the issue positions of other party supporters (Colloca and Corbetta, Reference Colloca and Corbetta2015).

While the traditional left-right cleavage in the Italian electorate may seem to provide unfavorable conditions for such ideologically inconsistent political party, M5S made inroads into the electorate in 2013 (Bellucci and Maraffi, Reference Bellucci and Maraffi2014), and even greater gains in 2018 when it succeeded in forming a government. Understanding the ideological camp from which M5S support and opposition originates remains an open question. We thus examine M5S support across the left and right-wing segment of the Italian electorate.

In sum, we investigate a period in Italian politics marked by severe political and economic instability. We draw on data from the five-wave Italian National Election Study (ITANES) conducted between 2011 and 2013 to trace the effects of partisanship over time. Thus, from a methodological standpoint, the ITANES panel provides a causal test of the influence of partisanship: We use expressive partisanship—measured in wave 1 in 2011—to predict political behavior in wave 5 in 2013. This two-year time interval creates a substantial temporal distance between the independent and dependent variables. With the additional political upheaval in Italian politics between 2011 and 2013, we test whether strong partisanship is a stabilizing electoral force—even in a shaky political system such as Italy.

5. Hypotheses

We test several hypotheses with data from the ITANES panel.

H1: Partisans who identify strongly with traditional left-right parties are more likely than weak partisans to vote for their party (expressive partisanship hypothesis).

H2: Partisans who identify strongly with parties on the traditional left-right axis in Italian politics are less likely than weak partisans to vote for the anti-establishment M5S and to favorably evaluate its leader Beppe Grillo (party system stability hypothesis).

For both H1 and H2, we remain agnostic as to whether the effect of strong partisan identity differs for partisans on the left and the right.

H3a: Non-partisans are more likely than partisans to vote for the anti-establishment M5S and favorably evaluate its leader Beppe GrilloFootnote 3 (dealignment hypothesis).

H3b: Non-partisans with higher levels of education are more supportive of M5S than those with less education (dealignment hypothesis).

6. Methods and data

6.1 Sample

The ITANES panel is a nationally representative five-wave panel conducted between February 2011 and March 2013 (Bellucci, Reference Bellucci2014; Bellucci and Maraffi, Reference Bellucci and Maraffi2014).Footnote 4 The data include separate phone and online samples (see online Appendix for details). The phone sample (CATI) contained 5309 respondents in wave 1 and ended with 1159 respondents in wave 5 (retention rate: 21.8 percent). The online sample (CAWI) started in wave 1 with 1496 respondents and ended with 908 respondents in wave 5 (retention rate: 60.7 percent). Our analyses are confined to respondents who completed waves 1 and 5 (N = 2067).

The panel data have two key limitations: high attrition across waves in the CATI sample and an unusually high percentage of partisans in the CAWI online sample (85.2 percent in wave 1 and 85.9 percent in wave 5) when compared to the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) 2006 benchmark (36.2 percent). High attrition rates in the CATI sample meant that the combined sample was more partisan in wave 5 than in wave 1 because of the loss of less partisan CATI respondents. In the combined wave 1 data, 48.7 percent of participants identified with a political party compared to 70.4 percent in wave 5 (see Table A1). The ITANES sample is thus more partisan and contains fewer non-partisans than the Italian population. The demographic and political makeup of the CATI and CAWI samples can be seen in Table A1. Given the potential drawbacks of combining different CATI and CAWI samples, we also present the main analyses separately for each survey mode in the online Appendix (Tables A8–A11), showing comparable results.

These limitations provide us with a sample of respondents who are politically more interested and are more likely to hold a partisan attachment than the rest of the population, where more than half of citizens do not have a party they feel closer to. Thus, the sample underestimates the presence of voters who are potentially more receptive to the appeal of populist forces.Footnote 5 Given that no other data are available to capture the evolution of partisan identity strength over time in Italy in 2011–2013, we decided to rely on the ITANES panel dataset but carefully address its shortcomings by examining CAWI and CATI separately as well as provide supplementary analyses when possible and useful to further support our argument.Footnote 6

6.2 Measures

Partisanship was assessed with the following questions: “Is there a political party that you feel closer to? If yes, could you please indicate which one?” Roughly half of wave 1 respondents and 70 percent of panel respondents were classified as partisan (N = 1460). All partisans were asked if they were “mere sympathizers” (45 percent), “somewhat close” (36 percent), or “very close” (18 percent) to derive a measure of traditional partisan strength.

Partisan identity strength (i.e., expressive partisanship): Expressive partisanship was measured using an eight-item scale adapted from Mael and Tetrick's (Reference Mael and Tetrick1992) Identification with a Psychological Group scale. This key variable was included in the first wave of the ITANES and asked of respondents who identified with a political party (see Table 1 for wording). Items were averaged, ensuring that almost all partisans in the panel (N = 1456 or 99.8 percent) obtained a valid score. The traditional folded partisan strength measure is moderately correlated with the partisan identity scale (r = 0.39, P < 0.001).

Table 1. Distribution of partisan identity items

Note: Entries are percentages from wave 1 of the ITANES data set.

Throughout the following analyses, we show that the identity scale has somewhat stronger predictive power than the traditional partisan strength item and better identifies partisans on the traditional left-right axis who are most likely to remain loyal to their political party than those occupying the political center. The greater political effectiveness of the partisan identity could be due to its stronger multi-item measurement, but that is consistent with our argument for better overall conceptualization and measurement of partisan attachments. The traditional item may detect both instrumental as well as expressive aspects of partisanship. From this perspective, the following results merely underscore that the traditional item is not a good substitute for the partisan identity scale.Footnote 7

In addition, we created two dummy variables to indicate whether a party is located on the traditional left or right of the ideological spectrum (see Table A2). We interact these variables with the expressive partisanship measure to determine whether it inhibits support for M5S to an equal extent on the left and right aisle of the ideological divide.Footnote 8

All dependent variables are measured after the 2013 election (wave 5), providing a particularly stringent test of the influence of partisanship assessed some two years earlier.

In-party vote was scored as 1 if partisans (measured in wave 1) voted for their party (in wave 5) and 0 if they voted for a different party.

M5S vote was a dummy variable coded 1 if someone voted for M5S in either the Senate or Chamber election.Footnote 9 Positive rating of Grillo was created by combining five ratings of Grillo from wave 5 (overall judgment, honesty, leadership skills, understands people's problems, better prepared than other politicians) (α = 0.83). Both variables were assessed in wave 5 after the election. An adjusted positive rating of Grillo variable was created by subtracting the average ratings of all the other leaders (on a 0–1 scale) from ratings of Grillo. This variable ranges from −1 (Grillo much more negative) to 1 (Grillo much more positive) and is included in analyses among partisans and non-partisans. The latter dislike most politicians and the adjusted scale measures respondents' relative liking of Grillo when compared to other political leaders.

We provide additional summary statistics and information on the construction of key dependent and independent variables in (Table A4). Last, we include a standard set of control variables that are associated with voting behavior, namely education which ranges from 0 (did not finish high school) to 1 (post-graduate education), age which is measured in decades, and employment status which is a dichotomous variable coded 0 (unemployed) and 1 (employed). All variables included in analyses are coded from 0 to 1.

7. Results

7.1 In-party support

First, we test the expressive partisanship hypothesis, which predicts that strong expressive partisanship boosts in-party support. In these analyses, we regress in-party vote in wave 5 onto (expressive) partisan identity strength, and its interaction with left-wing and right-wing dummy variables, as well as other controls measured in wave 1. Almost all (95 percent) of wave 1 partisans voted in the 2013 election (N = 1378). Notably, we focus on partisans but exclude M5S supporters from this analysis since, in this first analysis, we are interested more generally in the effects of partisan identity among supporters of established parties on the left and right when compared to established centrist parties. This results in the exclusion of 45 individuals, resulting in a total sample of 1333 partisans in the panel who voted in 2013.

As seen in model 1 in Table 2, there is a strong positive interaction between both left and right parties and partisan identity. This result indicates that strong partisans who aligned with a party on the traditional left-right axis in 2011 continued to vote for their party in 2013. This finding confirms the predictive power of expressive partisanship in the Italian political system as well as its long-lasting impact on Italian political behavior despite a period of political and economic turmoil.

Table 2. Determinants of in-party vote among partisans

Note: Logistic regressions with standard errors in parentheses. All variables are scaled to range from 0 to 1. The parties in the baseline category are centrist parties UDC and API. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

The predicted probability of voting for the in-party is plotted in Figure 1 across the range of partisan identity strength separately for parties on the left and right. The probability of voting for the in-party increases at a similar rate for both left and right partisans as partisan identity increases in strength. But those on the left were more inclined than those on the right to vote for their party in the 2013 election regardless of partisan identity strength.

Figure 1. In-party voting across partisan identity strength for partisans on the left and right.

Note: Predicted probability of voting for the in-party, based on analyses in Table 2. Dichotomous variables are held at their modal response; continuous variables are held at their mean.

We find substantially weaker effects for the traditional folded (three-point) strength item (see model 2 in Table 2). In this case, the single item would have underestimated the effect of partisanship on in-party voting. This arises, in part, because those strongly identified with centrist parties (the omitted category in Table 2) were far less likely to vote for their party as seen in the significant negative coefficient for partisan identity strength. This effect was not detected in analyses including partisan strength. Consequently, when the effect of partisanship is examined for all parties regardless of their left-right or centrist status both partisan identity and partisan strength predict in-party voting (Table A12). Overall, these results support our hypothesis that expressive partisanship is a key-stabilizing factor, especially for voters associated with a party on the traditional left-right axis, even in a party system marred by political and economic instability.Footnote 10

7.2 Voting for M5S

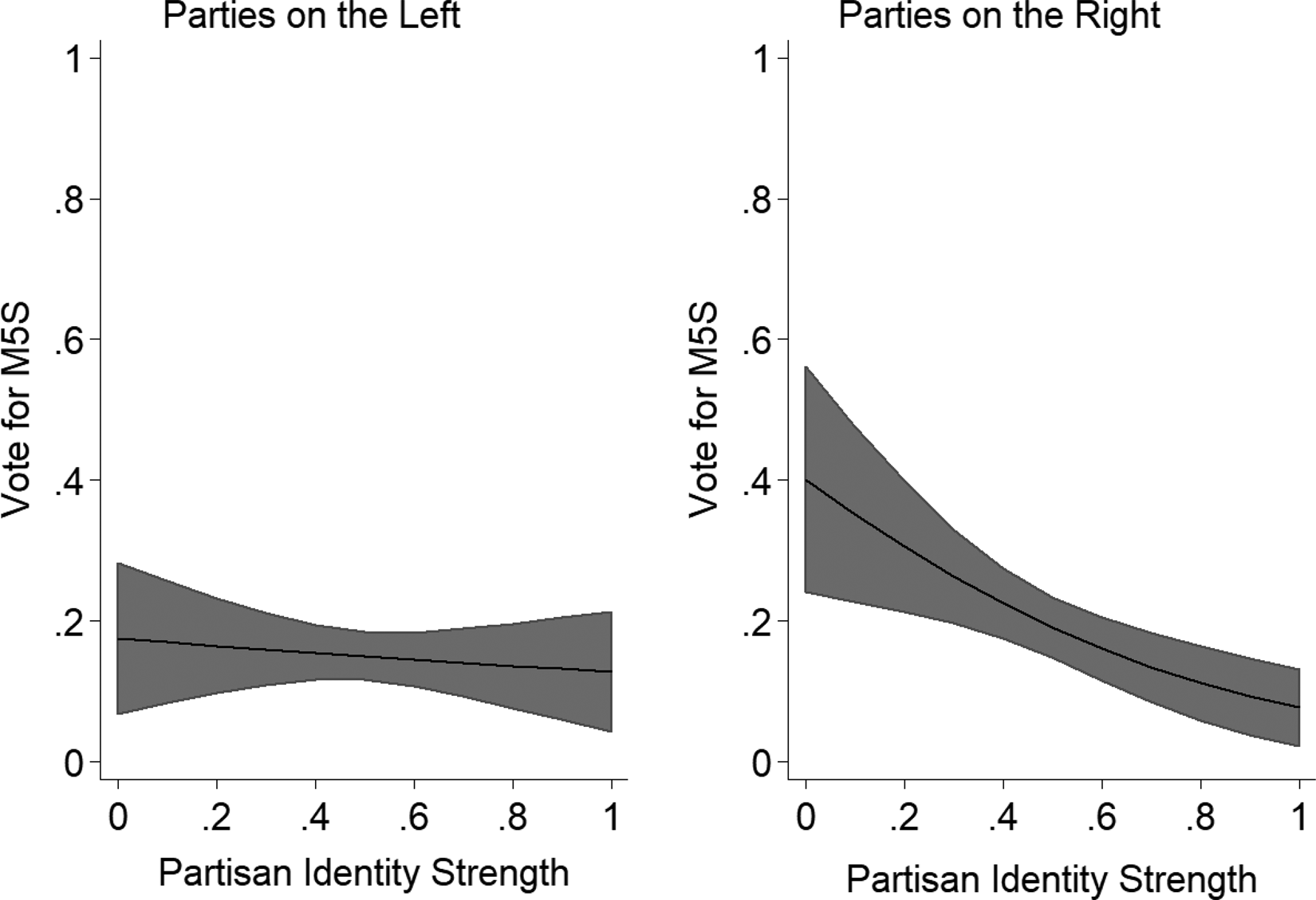

Our next hypothesis predicts that a strong partisan identity (i.e., expressive partisanship) with a party on the traditional left-right axis of Italian politics will have a negative effect on electoral support for M5S (system stability hypothesis). To test the effect of expressive partisanship, we regressed voting for M5S on partisan identity, an interaction between partisan identity and identification with a traditional left or right party, and other controls including survey mode (CATI or CAWI). We once again examine the effects of a strong identity with parties on the left and right separately to determine whether one or the other side of politics was more strongly resistant to the appeal of M5S. This analysis is confined to those who identified with a political party in wave 1, some two years before the election, and includes voters who identified with M5S in wave 1 increasing the total number of voting partisans to 1378.Footnote 11 Analyses are shown in Table 3 (model 1).

Table 3. Determinants of voting for M5S among partisans

Note: Logistic regressions with standard errors in parentheses. All variables are rescaled to range from 0 to 1. The parties in the baseline category are UDC, API, and M5S. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

As expected, both interaction terms between left or right party dummies and expressive partisanship are negative and one is statistically significant: Italians who identified strongly with a right-wing or left-wing party were less likely to vote for M5S although this only reached statistical significance on the political right. Thus, weak partisans on the right were more likely to vote for M5S than their more strongly identified partisan counterparts. Trends were in the same direction on the left but did not reach statistical significance. We thus conclude that strong expressive partisanship—especially on the right—reduced the likelihood of a vote for M5S in 2013. In addition, older, and better-educated respondents were less likely and employed respondents were more likely to vote for M5S.Footnote 12

Notably, there is no significant interaction between a folded version of the traditional partisanship measure (ranging from mere sympathizer to very close) and left and right parties (see model 2 in Table 3). Nonetheless, partisan identity and partisan strength both significantly decrease the chance of voting for M5S when their effects are examined across all parties (without a left-right party interaction; Table A13). This supports our general hypothesis that stronger partisanship decreases support for anti-establishment parties. Once again, the expressive partisan measure helps to better isolate this effect by revealing the negative effects of a strong partisan identity for those associated with parties on the traditional left-right axis.

To illustrate the magnitude of the effects in the first model of Table 3, we plotted the predicted probability of voting for M5S across the range of partisan identity strength (expressive partisanship) for parties on the left and right. In Figure 2, support for M5S decreases with increasing partisan identity strength on both the left and right, although effects are stronger on the political right in large part because weakly identified partisans on the right were especially likely to support M5S. Among those who identified with a right-wing party, the probability of voting for M5S was 0.40 among weak identifiers and about 0.10 for strong identifiers. In contrast, among partisans on the left, the probability of voting for M5S remained stable at 0.20 across the range of partisan identity strength. This steadiness suggests that partisans on the left did not consider M5S an appealing alternative—regardless of their partisan identity strength. We speculate that this immunity is grounded in the socio-cultural stances of the M5S' policy platform, especially with regard to immigration and the European Union at the time. Despite this appeal on the right at the time of data collection in 2013, M5S has since formed government alliances with both the right (i.e., Lega Nord: Conte I) as well as the left (i.e., PD: Conte II).

Critics might wonder whether the role of partisan identity in diminishing support for M5S is simply driven by the fact that stronger partisans—in general—tend to stick with their in-party—regardless of the presence of an anti-establishment party. For this purpose, we examined the impact of partisan identity on voting for an anti-establishment party, voting for another party, or voting for the in-party. A strong identity with a party on the traditional left or right axis was equally effective in decreasing support for an anti-establishment and another party (see Appendix Table A18). We thus conclude that partisan identity is equally powerful in diminishing support for any party, including anti-establishment parties. Notably, these effects would have remained undetected with the single-item partisan strength measure (see Appendix Table A19).

7.3 Grillo evaluations

The partisan stability hypothesis also predicted that strong expressive partisanship would lower the positive ratings of the M5S leader, Beppe Grillo. To test this hypothesis, we regressed Grillo ratings onto the same variables included in the previous analysis using a simple OLS regression model. Results are based on all partisans regardless of whether they voted and include wave 1 supporters of M5S, resulting in an effective sample size of 1460. The results are shown in Table 4. In line with previous findings, strongly identified partisans on the left and right rated Grillo less positively than those with a weaker identity, though the coefficient is only marginally significant (see model 1 in Table 4). These findings are more consistently symmetrical than observed for vote choice: Identifying strongly with a right or left party decreased Grillo ratings to roughly the same degree, providing evidence in favor of the expressive model of partisanship. In addition, Grillo ratings are less positive among older Italians underscoring the consistent negative effects of age on M5S support. Once again, we do not find any significant effects for the traditional partisan strength item (see model 2 in Table 4).Footnote 13

Table 4. Determinants of positive Grillo ratings among partisans

Note: Linear regressions with standard errors in parentheses. All variables are rescaled to range from 0 to 1. The parties in the baseline category are UDC, API, and M5S. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

We replicate this analysis without the left-right party interactions (Table A14) to compare the main effects of partisan identity and traditional partisan strength. Both partisan identity and strength significantly decrease ratings of Grillo regardless of party. The effect is roughly twice as large for identity than strength, however, in OLS regressions. This provides ballast to our argument that partisan strength is best measured with a multi-item identity scale.

7.4 M5S support among non-partisans

The previous analyses support the prediction that citizens with strong expressive partisan ties were less likely to vote for M5S in the 2013 national election. We turn now to examine the dealignment hypothesis (H3a) which predicts that non-partisans are more likely than partisans to vote for M5S and rate Grillo favorably. Non-partisans comprised a hefty percentage of respondents in wave 1 (48.7 percent) and it is important to understand whether they fueled support for M5S in the 2013 election. If partisanship serves to shield voters against anti-establishment appeals, non-partisans should be especially susceptible to the appeal of Grillo and M5S. Analyses of the M5S vote are based on 1901 voters in the panel and analyses of adjusted Grillo ratings are based on all 2067 panel respondents.

The findings in Table 5 support the dealignment hypothesis. Non-partisans (measured in wave 1) were significantly more likely than partisans to vote for M5S (measured in wave 5) (column 1). We also examined ratings of Grillo among partisans and non-partisans using the adjusted Grillo rating (to account for more negative ratings of all party leaders among non-partisans). Non-partisans evaluated Grillo (compared to other party leaders) more positively than did partisans (column 3). Overall, non-partisans were more likely than partisans to rate Grillo favorably and vote for M5S.

Table 5. Analysis of voting for M5S and adjusted ratings of Grillo among partisans and non-partisans

Note: Entries in the vote model are logistic regression coefficients; entries in the ratings model are linear regression coefficients. Adjusted ratings of Grillo was created by subtracting the average ratings of all the other leaders (on a 0–1 scale) from ratings of Grillo. Standard errors in parentheses. All variables are rescaled to range from 0 to 1. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

We also test the related hypothesis (H3b) that well-educated non-partisans are more likely than their less educated counterparts to vote for M5S. For this purpose, we include an interaction between a dummy variable for partisanship (0 indicating partisans and 1 indicating non-partisans) and education. These analyses are also shown in Table 5.

In earlier analyses confined to partisans, higher educational attainment reduced the likelihood of voting for M5S consistent with findings from other studies (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2009; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012). But the link between education and M5S vote or Grillo rating is more complex when data include partisans and non-partisans. As seen in columns 2 and 4 of Table 5, there is a significant positive interaction between education and non-partisanship indicating that better-educated non-partisans are most supportive of M5S and Grillo. In contrast, the coefficient for educationFootnote 14 (among partisans) is significant and negative, confirming the negative effects of education on the M5S vote observed earlier in Table 2.Footnote 15 Once again, older voters were less likely to support M5S, while those with a paid job were more likely to support it.Footnote 16

8. Discussion

Strong expressive partisanship increased in-party loyalty, dampened electoral support for M5S in the 2013 Italian election, and weakened the ratings of Grillo, the party's leader. M5S gained electoral momentum in 2013 but their support was more pronounced among those who were outside the party system or weakly aligned with a traditional left-right political party. Our findings thus lend support to the validity of the expressive partisanship model as well as its stabilizing effects in a politically tumultuous multi-party system.

The partisan identity and traditional single-item partisan strength measure both predict in-party voting, decreased electoral support for M5S in 2013, and less positive ratings of Grillo. Nonetheless, the partisan identity scale had stronger effects in some instances such as ratings of Grillo. It also revealed the greater stabilizing power of partisan attachments among supporters of the traditional left-right party axis in Italy. Strong supporters of centrist parties such as Alleanza per l'Italia (API) and Unione dei Democratici Cristiani e di Centro (UDC) were more likely to vote for an anti-establishment party whereas supporters of traditional left and right parties were far less likely to do so. Notably, these effects would have remained undetected with the standard three-point partisan strength item.

Critics might question the extent to which partisan affiliation uniquely dampens support for anti-establishment parties or, instead, deters support for any newly emergent political party—even traditional ones that fall within the pre-existing ideological blocs. Among partisans, we found that strong attachments to a traditional left or right party weakened support for anti-establishment and other parties. Among non-partisans, especially the better educated ones, we found stronger support for M5S. This suggests that the absence of partisanship generates ripe ground for support for anti-establishment parties. This is consistent with Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser's (Reference Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser2019) Chilean findings on alienated non-partisans. From this perspective, the absence of party attachments is crucial in providing an electoral opening for anti-establishment parties.

Our finding of stronger support for an anti-establishment party among better educated non-partisan Italians helps reconcile conflicting findings in the literature. Dalton's (Reference Dalton1996, Reference Dalton2014) cognitive mobilization thesis posits growing non-partisanship among the best educated. Yet, others report higher levels of partisanship among the best educated (Dassonneville, Reference Dassonneville2012), including in Italy (Poletti, Reference Poletti2015). We find that among non-partisans, higher levels of education are associated with greater support for M5S, consistent with Dalton's thesis that the best-educated are better able to map their views onto political parties and candidates. At the same time—consistent with Dassonneville (Reference Dassonneville2012) and Poletti (Reference Poletti2015)—better educated partisans are less likely to support M5S. As a result, better-educated non-partisans are more likely to support an anti-establishment party whereas better-educated partisans do not. From this perspective, the absence of strong party attachments is crucial in providing an electoral opening for anti-establishment parties among the better educated.

It is important to note that partisanship is not especially prominent in Italy, with only 36 percent of Italians claiming party affiliation in the 2006 CSES. Moreover, in our data, partisan identity was not particularly strong, averaging a modest 0.5 on a 0–1 scale among partisans. Thus, partisans and especially strong partisans constitute a small percentage of the Italian electorate, leaving the country vulnerable to the appeal of anti-establishment forces. This may help to explain the outcome of the 2018 Italian election in which M5S won a plurality of votes. To be clear, partisanship (or the lack thereof) is not the only explanation of political choices. Our goal was not to account for all possible explanations but to demonstrate the long-lasting impact and significance of (expressive) partisanship in a system that does not appear conducive to party loyalty.

We have shown that well-established partisan loyalties stabilize a political system even when the system is rocked by economic and political shocks. This resilience is especially important as a counterforce to anti-establishment appeals that challenge not just the political status quo, but also core democratic values such as civil rights and civil liberties. In sum, strong partisanship is an important feature of a stable party system.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.37. To obtain replication material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AINBOL