Hannah Pitkin's (Reference Pitkin1967) conceptualization of representation as multidimensional (i.e., formal, descriptive, substantive, and symbolic) has decisively shaped the way that research on women's substantive representation (WSR)—that is, acting for women—is done. For a long time, scholars have tended to limit their research on WSR to a single site, often the parliament, and a limited sets of actors (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008). While this approach might be fruitful when the research object is a liberal democracy with a separation of powers and personnel, it tends to fail when it comes to authoritarian regimes, where power is concentrated and social movements are regularly repressed. What happens when legislators are drawn largely from the executive branch, and both are under the rule of a single party? Where, by whom, and how is women's substantive representation produced in such political contexts?

In this article, we propose a state-society interaction approachFootnote 1 to the study of WSR in authoritarian regimes using a framework that includes different sites and actors that mobilize across the boundaries of a state's legislative and executive bodies. This approach responds to the proposal of Celis et al. (Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008, 99) to steer current research toward answering the question “where, how and why does the substantive representation of women occur” instead of focusing only on elected female legislators. China offers a unique case for the current field of WSR as it typifies a repressive political environment in which, under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), power is concentrated in the hands of Party cadres who often hold positions in multiple institutions simultaneously. As a result, the majority of legislative members, being full-time executive cadres as well, are restrained in their political autonomy and only selectively respond to their constituencies (Truex Reference Truex2016). In addition, although gender quotas are present in China's state administration and the training of women cadres has been an indispensable part of the CCP's socialist legacy, the separation of the political sphere of women (i.e., women's policy machinery) from the mainstream political domain has secured a certain rate of women's political participation but also placed significant restraints on women's access to the core of state power (Jiang, Reference Jiangforthcoming). For example, while 22% of legislators in China's parliament during the 1970s were women, the percentage of women in the CCP's Politburo has never exceeded 10% and has mostly remained at 0%. Lastly, women's social movements in China, which used to be monopolized by Party-authorized organizations, are now engaging in new forms of activism (Angeloff and Lieber Reference Angeloff and Lieber2012; Wang Reference Wang2017). Studying WSR in such political contexts therefore requires us to look beyond legislative bodies, refuse a static understanding of representation, and focus on the chains of actions connecting the state and society.

Building on the complexity of China's political institutions, this article examines how WSR is produced in China by asking two questions: (1) What is the institutional structure of women's substantive representation like in China? (2) How are women's interests recognized, communicated, and substantively represented through various gender lobbying mechanisms? By gender lobbying, we mean political processes and activities initiated by individuals, social groups, or organizations that aim to persuade legislative representatives, government officials, or political authorities to sponsor and support laws, regulations, or programs that enhance women's interests and improve gender equality.

This article draws from primary sources including reports, autobiographies, and legislative records, as well as semistructured interviews conducted during multiple fieldwork trips in three provinces—Hunan, Hubei, and Guangdong—from 2016 to 2020. Core interviewees included 76 individuals, among whom 23 were members of the Women's Federation, 19 were legislators from the local and national levels, 23 were Party-state cadres, 9 worked for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and 2 were lawyers. Interviews typically lasted one to two hours, and more than a third of our sources were interviewed multiple times. As we were purposefully looking for interviewees working to advance women's interests, our snowball sample includes only one male interviewee.Footnote 2

Building on these sources, this article constructs two comparative case studies to examine China's gender lobbying mechanisms for the ongoing debates on domestic violence and sexual harassment. The case selection originates from two considerations. First, both issues are reflections of Chinese women's collective experiences and have attracted heated discussion in recent years demanding state action (Leggett Reference Leggett2017; Lin and Yang Reference Lin and Yang2019). Second, the two cases have experienced very different paths of mobilization and contrasting results: while the lobbying against domestic violence resulted in the promulgation of China's first specific law against domestic violence, the lobbying on anti–sexual harassment only led to a few local or university-initiated regulations and heavy state repression.

We argue that WSR in an authoritarian context such as in China originates neither from a single site, nor even several sites within the state. Instead, it is embedded in the interconnectedness of different sites and actors and relies on tight collaboration between them. Successful lobbying often involves the All-China Women's Federation (ACWF or WFs when referring to its branches), the women's policy machinery sponsored by and subjugated to the CCP, which plays a central role in collecting grievances, building coalitions with other actors, and pushing forward the legislative process. While the ACWF members’ simultaneous appointment to different institutions (e.g., the legislature and CCP) is critical in coalition building, it also means that their pursuit of WSR in China is largely constrained by and secondary to the priorities of the CCP, leaving more sensitive gender issues untouched.

REVISITING CURRENT POLITICAL REPRESENTATION AND WSR THEORIES

While classic political theorists such as Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) assume that political representation depicts the fundamental relationship between the elected and their constituencies, many have expanded the understanding of political representation to a broader institutional context. Among them, Michael Saward (Reference Saward2010, 93) marks the constructivist turn, arguing that representation is not a theory that is only pertinent to a specific type of political regime, but encompasses the fundamental social relations and power dynamics that run through society from a holistic perspective. Scholars have consequently refuted the notion that democracy should be the premise of representative studies, as de facto representative loops that act as key instruments bridging the interests of the citizens, representatives, and upper-level authorities can be found in many authoritarian regimes (Sintomer and Zhou Reference Sintomer and Zhou2019). Instead of imagining representation as a unidirectional principal-agent scheme and limiting our analysis to elected representatives, we must focus on how representation is undertaken by actors based on collective grievances.

Although the scholarship on WSR has made fruitful contributions in the last few decades, it faces challenges similar to those mentioned earlier. The lack of discussion of nondemocratic contexts severely limits the research on WSR to only 55.8% of the world's population (Roser Reference Roser2015). While literature on gender politics outside democracies exists, these studies have focused more on how women participate in politics, or they have discussed women's issues without engaging with the WSR theory. For instance, there is a rich body of scholarship on women's representation in communist and postcommunist regimes, in which authors observe that progressive ideologies and state-provided welfare play a dual role in advancing women's interests while exploiting women's liberty and labor (Bystydzienski Reference Bystydzienski1989; Matland and Montgomery Reference Matland and Montgomery2003).

Recent years have seen more, albeit still limited, systematic exploration of the relationship between authoritarianism and WSR. For instance, Aili Mari Tripp (Reference Tripp2019) has argued that political regime might play a significant role in predicting the results of WSR in different domains. Daniela Donno and Anne-Kathrin Kreft (Reference Donno and Kreft2019) found that among all types of autocracies, party-based regimes are more likely to promote women's political and economic rights, incentivized by party coalition building. In China, scholars have also made important contributions by examining women's roles in village-level governance and identifying the difficulties arising from converting a quota-based descriptive representation to a deliberation-based WSR (Jacka and Sargeson Reference Jacka and Sargeson2015; Sargeson and Jacka Reference Sargeson and Jacka2017). This article, building on this new literature, broadens the political context that the discussion of WSR holds as relevant and adopts a state-society interaction approach to examine gender lobbying mechanisms beyond a single site.

FRAMING WOMEN'S INTERESTS IN THE CHINESE CONTEXT

Defining women's interests is crucial in realizing WSR (Sapiro Reference Sapiro and Phillips1998). Feminist theorists have suggested that there might be internal ambivalence behind the term “women's interests,” as it aims to tackle gendered structures, on the one hand, and risks essentializing women as a homogeneous group, on the other (Childs and Lovenduski Reference Childs, Lovenduski, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Laurel Weldon2013). There have been numerous historical variations in the understanding of women's interests in China, and it has always been a field characterized by power struggles. As Wang Zheng (Reference Wang2005) has argued, state feminists—namely, women cadres leading women's movements under the CCP's leadership and within state bureaucracies—in China's socialist era have made efforts to negotiate with top male Party leaders and promote what they understood as women's interests in each period. For instance, state feminists advocated for women's interests in the provision of maternal care in the early 1950s, the promotion of equal labor and political participation during the 1960s and 1970s, and the elimination of gender discrimination and gender-based violence since the 1990s (Manning Reference Manning, Franceschet, Krook and Tan2019). In China's reform era, state feminists have increasingly come under international influence, exemplified by the way the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) shaped domestic understanding of women's civil, cultural, and political rights (Liu Reference Liu2006; Wang and Zhang Reference Wang and Zhang2010).

Current Chinese society sees two approaches to defining women's interests. On the one hand, the CCP and the state feminists sponsored by the CCP play a deterministic role in officially defining and interpreting women's interests, and all gender lobbying processes are mandated to build upon such definitions and interpretations. The existing laws and regulations provide de jure definitions of women's interests, which serve as juridical, governmental, and societal objectives in the pursuit of gender equality. The most important law to establish the framing of women's issues in the contemporary era is the Law on the Protection of Women's Rights and Interests, promulgated in April 1992. It defines a wide range of women's rights in politics, the economy, family and marriage, health care, and so on. For instance, it states that on political rights, “Women shall have equal rights to vote and stand for election as men do” (Article 8), and on personal safety, “Discrimination, abuse, and cruelty to women are prohibited” (Article 2). In parallel, there are other general laws (e.g., the Constitution and Civic Law) in which women's interests are mentioned in specific articles and “Action Programs” that plan and quantify the improvement of women's rights by the State Council.Footnote 3

However, these legal or policy-based definitions of women's interests are impractical, strategic, and politically bounded at the same time. The laws and policies do cover the basic principles of gender equality: men and women should hold equal rights in all domains; discrimination against women is a crime. These principles, however, mostly emerged as top-down as part of China's governance goals instead of produced by extensive public deliberation. The discrepancy between how the law works in theory and the social reality rampant with gender inequalities has rendered most gender legislation in China merely guidelines instead of implementable laws. In addition, such gender legislation also serves to legitimize the CCP's governance by “usher[ing] in a modern state devoid of ‘feudal’ practices” and conforming to international norms (Angeloff and Lieber Reference Angeloff and Lieber2012, 19). Such strategic motivations lead to a Party-centered approach to defining women's interests, which requires women's interests to be visibly addressed by laws and regulations, as long as they serve the CCP's consolidation of power and societal stabilization (Zhou Reference Zhou2019).

The second approach to defining women's interests relies on civil society. In the last decade, the current legal framework of women's interests started to show its limit, faced with the voices of grassroots and online feminists who are playing an increasingly important role in defining women's interests. The agenda of nonstate actors, including, for example, women's land rights, labor rights, and tackling gender-based violence, is not always in line with the interests of the CCP and therefore cannot be adequately resolved by existing laws and policies (Howell Reference Howell1996; Sargeson and Song Reference Sargeson, Yu, Jacka and Sargeson2011). Meanwhile, many more radical lines of women's interests are emerging in China's rapidly globalizing and liberalizing society, such as educated women's pursuit of economic independence and uncooperative attitude toward marriage, and a more diverse sexuality (Wu and Dong Reference Wu and Dong2019). Their means of advocacy, including performance art, protest, and online campaigns, are frequently met with strong state repression (Fincher Reference Fincher2018). While these practices might be crucial in stretching the boundary of state-defined women's interests, they are also limited by the increasingly strict political control of China's Xi Jinping era. Taken together, the concept of women's interests in contemporary China is a multilayered one that is constantly being defined and redefined. While the CCP draws the political boundary by codifying certain women's interests into laws and regulations, this boundary is subject to challenges from nonstate actors. Whether and how the CCP responds to such challenges, as expanded in the case studies, shapes the mechanisms and outcomes of gender lobbying.

POLICY-MAKING AND GENDER LOBBYING IN CHINA: INSTITUTIONS AND CRITICAL ACTORS

Policy-making in China is often viewed as unified and top-down, as the government is overtly subjugated to the rule of the CCP and organized hierarchically. While institutionally, the government is distinct from the CCP, it is a norm for major leaders to hold both Party and government posts. Such cross-appointment is also seen in the legislature. As legislators only work part-time, they might also be full-time government cadres, CCP members, or members of the WF. In addition, unlike in democracies, Chinese cadres are managed by the upper-level administration rather than elected by citizens. Therefore, it is not surprising that China would adopt an efficient policy-making process, as there are no institutional checks and balances (Truex Reference Truex2020).

Nevertheless, recent studies have challenged such a view and identified “fragmented authoritarianism” within China's policy-making process, characterized by increasing pluralization and responsiveness (Mertha Reference Mertha2009; Truex Reference Truex2016, Reference Truex2020). This fragmentation indicates not only intense interbureaucratic bargaining, but also the strong influence of nonstate actors (Mertha Reference Mertha2009; Tanner Reference Tanner1995). It is widely agreed that successful policy change in China benefits from three conditions. First, citizen grievances, especially with the threat of collective action, are more impactful than previously suggested and often result in fast responses (Chen, Pan, and Xu 2018; Truex Reference Truex2020). Second, policy entrepreneurs—that is, “advocates for proposals or for the prominence of an idea” (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995)—are equally critical in shaping policy outcomes (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2009; Mertha Reference Mertha2009). As Mertha (Reference Mertha2009) records, Chinese businessmen's persistent lobbying eventually brought key Chinese officials to negotiate with the European Commission on the issue of international trade, an area that is extremely unlikely to be influenced by nonstate actors. Lastly, national legislative success depends on support from the politically powerful ministries, and fighting among ministries easily delays the process (Tanner Reference Tanner1995; Truex Reference Truex2020).

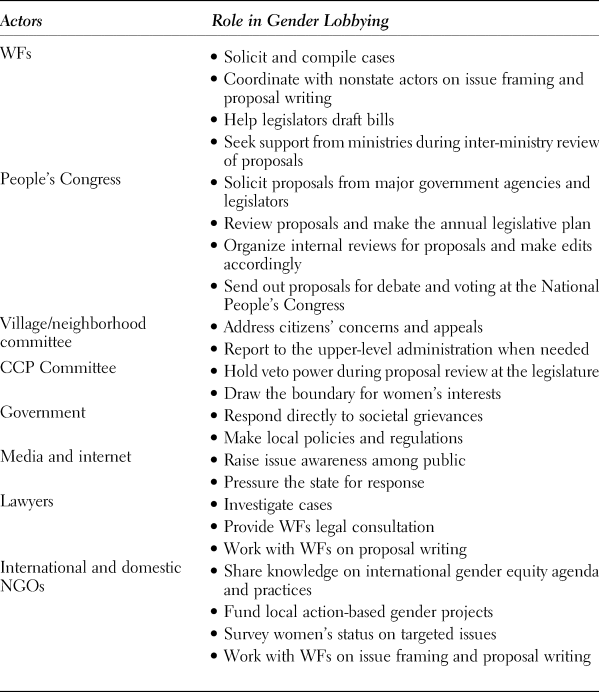

This study shows that gender lobbying is not a unified process either. It is diffused across state and nonstate institutions and actors. Compared with other fields, we have identified several unique characteristics of the critical actors, defined by Childs and Krook (Reference Childs and Krook2009, 127) as “those who act individually or collectively to bring about women-friendly policy changes”: the WF system takes a central role; lobbying largely targets legislative changes; and a broader range of policy entrepreneurs, including media partners, lawyers, and NGO workers, are involved (see Table 1).

Table 1. Critical actors and their roles in China's gender lobbying

To start with, the Party plays the role of drawing political boundaries, and the government addresses policy changes more directly in China's gender lobbying. While many participants in gender lobbying are CCP members, the CCP committees’ organizational control over specific lawmaking has eroded greatly in recent years (Cho Reference Cho2002; Tanner Reference Tanner1995). With no female cadre in the Standing Committee of the CCP Politburo and only 4% women in the Politburo, the CCP has hardly become directly involved and is seen mostly backstage, setting the ideological and political tone that guides the government and legislature, and only intervenes when the matter is ideologically or politically threatening. However, indirect involvement can be just as powerful, or even more so. For example, since the CCP started tightening its grip on domestic NGOs’ international connections in 2013, many local WFs have voluntarily suspended their ties with international organizations, including some renowned ones such as the Ford Foundation. In other words, the CCP is able to mobilize self-censorship among critical actors as well as order direct repression when the lobbying process is considered risky and destabilizing.

As the designated women's policy machinery under the CCP, the ACWF has unparalleled influence on agenda setting and intrastate lobbying. But its relationship with the CCP also complicates its role and practices. First, the ACWF bears an innate responsibility to represent women. According to its own manifesto, the WF “defends women and children's lawful rights, listens to women's opinions, passes women's suggestions to the state agencies, and demands that other state agencies work on cases in violations of women and children's interests and coordinates with them when they do” (Chapter 1, Article 4). In practice, the ACWF lobbied successfully for the passage of the Law on the Protection of Women's Rights and Interests in 1992 and the inclusion of a 22% gender quota for the national legislature in 2007 (Angeloff and Lieber Reference Angeloff and Lieber2012). However, as the “good daughter of the Party,” the ACWF's agenda has always shifted along with the CCP's priorities (Zhou Reference Zhou2019). For instance, it played a controversial role in implementing the One Child Policy in the 1980s and in the recent “Family Values” campaign advocating women's maternal roles ordered by the Party (White Reference White2006; China Daily Reference Daily2019). In addition, its marginal status as a mass organization (quntuan zuzhi) instead of a full government department, and the fact that its agendas are determined from above, compromise its capacity and incentive to address women's grievances. Concretely, as seen in the case of village WFs, female villagers often choose to take their concerns to the male members of the village committee over the female WF chairperson because of their lack of resources (Jacka and Sargeson Reference Jacka and Sargeson2015).

Despite that, the ACWF has a particular advantage in gender lobbying. The physical omnipresence of the WFs’ offices at every level of government and the establishment of a nationwide “women's rights hotline 12338” mean that the WF is capable of mobilizing its personnel and resources when needed.Footnote 4 According to the head of a local WF, from May to December 2019, the WF collected a total of 400 inquiries.Footnote 5 Theoretically, after receiving the inquiries, local WFs have to address the issues and compile the reports, ready to be reviewed by the superordinate WFs. While such reviews are often imposed from above, local WFs’ records of visits and phone calls are of great help when the ACWF needs such data to back up its lobbying. In addition, even though the WF is marginalized in the government, its close ties with the CCP and other state agencies enable its strategic navigation of the system (Wang Reference Wang2017).

With their connections to citizens and eligibility to propose bills, legislators act both as lobbying actors and as the target of lobbying by other political entrepreneurs. According to the Law on Deputies of the National and Local People's Congresses, representatives must “maintain close ties with constituents from the electoral districts, [and] listen to and report their concerns and inquires” (Article 4). To facilitate such obligations, their contact information is made available through online platforms and physical banners at the village/neighborhood committee's office. Complaints and suggestions are directed by representatives to government bureaus for resolution or brought to the annual assembly for further discussion if the matter is beyond the capacity of a single bureau (Manion Reference Manion2015). While legislators often propose bills drawing from their geographic constituencies, they are also the targets of lobbying. As seen in the lobbying against domestic violence, both state and nonstate actors sent their draft proposals to the same legislator.

Another supportive lobbying actor is the village/neighborhood committee. The grassroots character of the committees and committee director's authority within the village/neighborhood make these committees especially appealing for local women. For example, a survey by Jiang et al. (Reference Jiang2006) of 1,255 citizens showed that 10.3% of domestic violence victims reported to the committees first, which is more than the 6.2% who called for police support. As de facto the lowest administrative level, village/neighborhood committees play a key role in implementing state policies. Concretely, it is common for female villagers or citizens to visit the office for consultations on all sorts of matters, including issues concerning women's interests.

Lastly, nonstate actors, including both domestic and international NGOs and activists, as well as lawyers, are gaining more prominence in lobbying. Domestic NGOs are particularly helpful in issue framing, as many are founded by former journalists who are well connected in the media and able to increase public attention to influential outlets. As many lawyers and legislators are also members of NGOs, it is not uncommon to see NGOs draft bills and hand them to the Congress through legislators. International NGOs and activists, such as the Ford Foundation, have funded many gender advocacy projects since the 1995 World Conference on Women (Wang and Zhang Reference Wang and Zhang2010). Not only do domestic actors use international practice to justify their lobbying (Liu Reference Liu2006), information exchange at the societal level also helps raise public awareness, as seen in the case of both domestic violence and sexual harassment.

Among all critical actors and institutions, policy changes follow the ACWF's lead through several mechanisms. First, the chairperson of the village/neighborhood-level WF, who is also a member of the village/neighborhood committee, has access to the record of villagers’ appeals. Such access guarantees that when the upper-level WF inquires about women's concerns, the village WF is capable of compiling them. In some cases, the upper-level WF mandates regular reports to monitor women's status within its jurisdiction. According to two members of the Hunan Provincial WF, during their lobbying of the Provincial Congress on the issues of domestic violence and women villagers’ land rights, lower-level WF efforts to collect cases helped them convince legislators of the urgency of such matters.Footnote 6 Second, the People's Congress and the ACWF have an interdependent relationship during legislation. The WFs rely on the representatives’ sponsorship to make policy change. The legislators, on the other hand, need the WFs’ expertise to help draft bills. In conclusion, quoting a member of the Hunan Provincial WF, the advancement of women's interests in China is rooted in “our WFs’ mutually dependent relationship with other state institutions” (ni zhong you wo, wo zhong you ni).Footnote 7 However, having an entirely Party-defined gender agenda brings both advantages and limitations: can such a state-centered institutional setup allow women's voices to be heard from the grassroots? Can such a seemingly top-down system facilitate social movements that contest the current gender program? The next section of this article addresses these questions by using comparative case studies in which this state-centered WSR is confronted by new demands.

LOBBYING FOR WOMEN IN AUTHORITARIAN INSTITUTIONS

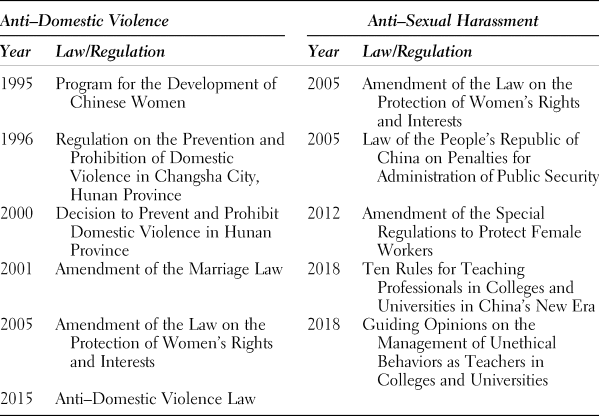

This section analyzes two contrasting case studies: (1) the lobbying process against domestic violence and (2) the movement of anti–sexual harassment activism (see Table 2). Through the comparison of gender lobbying mechanisms, we show how women's collective demands need to be formally recognized by women's organizations and legal experts based on the compilation of large numbers of severe cases before entering public debates and political negotiations. In the latter part of this lobbying process, strong alliances among state and nonstate agents acted as a decisive element for effective legislative lobbying.

Table 2. Laws and regulations on domestic violence and sexual harassment in China

Case Study 1: Anti–Domestic Violence Legislation (1995–2015)

The Chinese proverb “even an upright official cannot settle a family quarrel” illustrates well the difficulty of anti–domestic violence (ADV) legislation. For a long time, domestic violence was normalized in China as “couple fighting,” and thus it was not political and not something for which anyone would be held accountable. Concretely, although China was among the first group of signatories ratifying the CEDAW in 1980, it took more than three decades to achieve the enactment of a nationwide ADV law in 2015.Footnote 8 Before that year, several official documents had included clauses addressing the issue of domestic violence, yet the wording often lacked specifics for enforcement. Examples include the Program for the Development of Chinese Women (1995–2000), which stated that the state should “protect women's equal status in the family and prevent the happening of domestic violence.” Similarly, in the 2001 amendment of the Marriage Law, the Congress included several articles on domestic violence, including, for example,

Where a person indulges in domestic violence or mistreats a family member, the victim shall have the right to advance a request; the neighborhood committee, village committee, or the work unit they belong to, shall persuade the person to stop doing it [ . . . ] the public security shall, in accordance with the legal provisions on administrative penalties for public security, impose an administrative penalty on the person who commits domestic violence. (Article 43)

However, the Program for the Development of Chinese Women was, first and foremost, a guiding document and by no means legally binding. Similarly, the use of the term “shall” and the inclusion of several state institutions without clarity on each's mandate in the Marriage Law left the case to local agencies’ discretion. With the cultural interpretation of domestic violence as a family matter, this discretion often resulted in inaction or buck passing. Worse still, as the legislator who drafted the ADV proposal recalled, these laws were used to justify that “we do not need a law specifically addressing domestic violence as it has been included in other laws” (Luo and Zhang Reference Luo and Zhang2016).

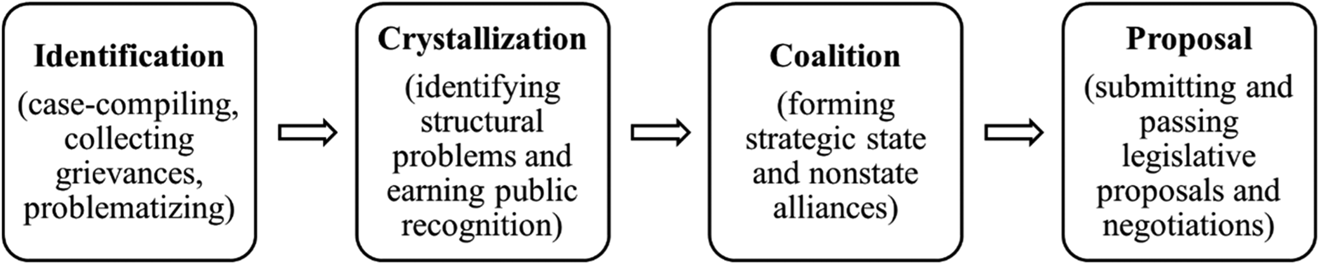

The ADV advocacy started almost simultaneously at both the local and national levels, and from both within and outside the state.Footnote 9 Hunan Province became the first local government in China to make an ADV enactment in 2000, which was contagious—by the end of the year, 13 provinces and prefectures had passed a local statute addressing domestic violence. These local legislations not only put pressure on the national congress, but also contributed to the national advocates’ experiences and lessons. As a result, we see that the local and national legislation followed a similar process, summarized as case identification and compilation, advocates’ crystallization of cases, coalition building, and eventual submission of proposals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lobbying mechanism for anti–domestic violence.

Identification

Domestic violence started attracting the attention of several Party-affiliated women's organizations in the early 1990s at both the local and national levels. At the local level, through the WFs’ petition channel, the Department of Rights at the Hunan Provincial WF received thousands of letters from female citizens over a number of years, and many included atrocious details of domestic violence.Footnote 10 These personal accounts of grievances left a strong impression on the WF cadres responsible for receiving letters. As the head of the department, Qing, recounted, “All I did at that time was reading letters. I cried a lot. I had never heard about the term ‘domestic violence’ then. But I knew women should not suffer that” (Zhang Reference Zhang2000). Meanwhile, the same issue had also earned the attention of the Maple Women's Psychological Counseling Center, one of the earliest nongovernmental women's organizations in China.Footnote 11 Many volunteers at the Maple were members of the national WF, and therefore Maple worked closely with the WFs. Through its hotline providing consultations for women, the repeated mention of the term “couple fighting” caught the volunteers’ attention (Keech-Marx Reference Keech-Marx and Unger2008; Luo and Zhang Reference Luo and Zhang2016). Without strong support from the grassroots-level WFs, Tao, a volunteer from Maple and a professor at China Women's University, decided to conduct an investigation herself. Altogether, Tao visited 30 rural and 30 urban households in the Beijing area that had reported domestic violence to understand the patterns and solutions (Luo and Zhang Reference Luo and Zhang2016). The written reports and records of victimhood made it possible for women's organizations to first publicly identify and acknowledge domestic violence as a severe offense to women's health and security.

Crystallization

We identify crystallization as the process during which actors started investigating and analyzing the issue, especially its patterns and systematicity, with the purpose of raising public awareness and earning public recognition for successful lobbying. While several actors, such as Qing and Tao, noticed the severity of domestic violence, domestic violence still lacked widespread public recognition and attention in the early 1990s. When Qing first brought up the issue during the discussion of the legislation on the Implementation of the Law on the Protection of Women's Rights and Interests in Hunan Province in 1994, she was quickly turned down because “never had any province in China included such a term in their local laws. Other issues such as housing and land rights are more tangible and urgent” (Zhang Reference Zhang2000). The lack of public recognition soon had its solution: The Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, where international norms acted as a strong catalyst for domestic publicity of ADV. As Qing recounted,

The 1995 Beijing Conference was like a breeze in spring. To prepare for this conference, the term domestic violence made constant appearances on Chinese newspapers. Many journalists started reporting on China's domestic violence cases or introducing how foreign countries address it.Footnote 12

Meanwhile, seizing this moment, the founder of the Maple, Wang Xingjuan, organized a panel on domestic violence at the 1995 NGO Conference in Beijing despite pressure from the CCP not to tarnish China's image, marking Chinese NGOs’ first step in bridging the domestic and international discussion on ADV in a systematic fashion (Luo and Zhang Reference Luo and Zhang2016).

The second hindrance came from legislators’ recognition, which was highly contingent on actors’ strategic use of the compiled cases. Learning her lesson from 1994, Qing mobilized all WFs within the province and built a data set that included all petition cases received by the Hunan WFs across the provincial, prefectural, and county levels from 1995 to 1997, which totaled 29,388 (Hunan Women's Federation 1998). Astonishingly, domestic violence accounted for more than a quarter of all these—that is, 7,876 cases (Hunan Women's Federation 1998). Qing and her team at the provincial WF selected 254 cases with variation regarding the abusers’ education, economic status, and occupation, aiming to show legislators the systematicity of domestic violence (Hunan Women's Federation 1998). Later, during the national legislation stage, the same strategy was adopted by one of the major actors, the China Law Society Domestic Violence Network and Research Center (the Network) (Keech-Marx Reference Keech-Marx and Unger2008). The core members of the Network included professors from the Chinese Academy of Social Science and China Women's University with backgrounds in law and sociology, journalists from People's Daily and China Women's Daily, and members from the ACWF. From 2000 to 2001, in order to prepare their lobbying and persuade the legislators, the Network distributed 4,000 surveys in nine prefectures across three provinces and 1,000 surveys to judiciary members inquiring about the need for national legislation on domestic violence (Luo and Zhang Reference Luo and Zhang2016).

Coalition and Legislation

CoalitionFootnote 13 building involves two parallel processes: an interdepartmental one between WFs and other state agencies, and another between state and nonstate actors. As the head of the Department of Rights at the National WF recalled, the key for the fight against domestic violence is a multidepartmental cooperation mechanism (Jiang Reference Jiang2014). At the local level, the Hunan WF strategically used its status within the Party-state to secure support from the Provincial Congress. When the Hunan Provincial People's Congress started soliciting new legislative proposals, the Hunan WF, as a member of the Judicial Affairs Committee of the Congress, was qualified to make proposals during the solicitation. It was at that time that Qing first proposed legislation on domestic violence.Footnote 14 The dual identities of the WF's chairperson, Mei, as the Standing Committee member of the Hunan Congress and her membership of the Judicial Affairs Committee, also gave the WF resources unavailable to nonstate actors. The overlapping personnel meant that Mei was able to mobilize support in the Judicial Affairs Committee for the adoption of the legislative proposal. Then, before the proposal went to the voting stage, Mei used her network and put the WF's report on the 254 cases into every Standing Committee member's hands. As Qing explained about the coalition building, “they [legislators] are different from us. They probably have never seen or read about domestic violence. It is our job to show them the reality and win their support.”Footnote 15

The coalition building during the national legislation was mostly between the ACWF and nonstate actors. Unlike the WF, nonstate actors are not qualified for proposal making. Therefore, when the Network finished its national survey, as a member from the Network remembered, “everyone [from the Network] was trying to use their connections to approach legislators” (Luo and Zhang Reference Luo and Zhang2016). With a shared mission to serve women's interests, the Network soon targeted the WF as its “insider,” especially those WF members who also served as congressional members. The year 2008 witnessed a critical moment in the Network's coalition building process when it cohosted a meeting with the Heilongjiang Provincial WF. Participants in this conference included both nonstate actors and WF members from the local and national levels, including the head of the ACWF's Department of Rights. During the conference, Network members reiterated the urgency of an enforceable law against domestic violence, as the current administrative and legal frameworks “are mainly principle-based and almost impossible to enforce” (Chen Reference Chen2008). This meeting was fruitful: the head of the ACWF Rights Department promised that ADV legislation would be the preoccupation of her department. She kept this promise, as the ACWF started drafting proposals immediately and continued for the next six years, until the proposal finally entered the annual legislative plan in 2014. Similar to the Hunan WF's use of its status as an insider of the Party-state system, the national WF demanded several meetings with the Judicial Affairs Committee to push the proposal forward. The coalition of state and nonstate actors went beyond access to the content of the proposal. While the national WF started handing legislative proposals to the National Congress through legislator Tao, the same person who started the battle against domestic violence in the early 1990s, the Network also drafted a proposal and handed it to Tao. Tao merged the two drafts instead of taking one to the floor. As she explained, “The WF's organizational structure decided that its proposal is quite comprehensive since it has branches all over the country. NGOs do not have that. But they can be more focused on one issue area and thus dig it deeper” (Tao, cited in Luo and Zhang Reference Luo and Zhang2016).

Building on years of lobbying efforts, the ADV legislation eventually owed its timing to several major shocks to public opinion. At the local level, the proposal submitted by the Hunan WF was admitted in the 1996–97 legislative plan, three years after the Hunan WF started its lobbying. While the WF's efforts were undeniably crucial, a case of domestic violence in 1996 was cited as a trigger for the bill's admission to the legislative plan.Footnote 16 On January 4, 1996, 37-year-old Yizhao Yao from the capital city of Hunan Province was pushed out of a sixth-floor window by her husband after requesting a divorce because of years of domestic violence. The incident directly triggered the municipal government's release of an executive regulation within the very month, Regulations on the Prevention and Suppression of Domestic Violence. As the first regulation in Chinese history addressing domestic violence, this document set a precedent for the Hunan Congress for state intervention in an area previously considered private and opened up possibilities for further intervention. At the national level, while it took six years from the ACWF's submission of a proposal to its admission to the legislative plan, the bill passed within a year of its admission. Considering that it takes, on average, 4.69 years between a law entering the legislative plan and its passage (Truex Reference Truex2020), the Law against Domestic Violence was undoubtedly on the fast track. A major contributor to its fast passage was the accusation of domestic abuse against a celebrity, Yang Li, in 2013. The case attracted unprecedented public attention and spurred discussion on domestic violence. Li was interviewed by over 40 media outlets, including the New York Times, People's Daily, and China Central Television; during the interviews, he persistently denied the accusation and called the case a family quarrel. In the conclusion of this case, the court found Li guilty of domestic violence and issued the first restraining order handed out in Beijing based on the 2013 Civil Procedure Law.

In 2000, with a record of 57 votes out of 60, the Hunan Congress passed the Resolution on the Prevention and Suppression of Domestic Violence—the first local ADV law in China that held the police department and prosecutors accountable for omission (Jiang Reference Jiang2014). Fifteen years later, the National People's Congress passed the bill against domestic violence, making it the first national ADV law to recognize domestic violence as a criminal offense and to stipulate the state's intervention. Most importantly, it provided enforcement guidelines, including restraining orders by the local police department and protection orders from the court (Leggett Reference Leggett2017). Some provinces such as Guangdong went even further to streamline the fragmented bureaucracy (e.g., the police department, neighborhood/village committee, and WF) in law enforcement by assigning the case to the first responding agency the victim appeals to.Footnote 17

Summarizing the battle against domestic violence, we argue that it was a gradual process that first involved compiling information on the case, then winning support from within and outside the state and across multiple institutions, and punctuated by a shock to public opinion that sped up the state's response. The WF stood at the core of this process. Its hierarchical structure across all levels of government helped with the compilation of data from the very bottom and thus the justification for the legislation. Its identity as a CCP-sponsored organization also placed it as the core in coordinating with both state and nonstate institutions.

Case Study 2: Anti–Sexual Harassment Movement (1995–Present)

The year 2018 marked the rise of the global feminist #MeToo movement, a movement in which victims of sexual harassment and assault and gender-based discrimination denounce their male colleagues and superiors in the workplace. Many Chinese women also used online forums to share their testimony of being sexually harassed or assaulted by advisors, colleagues, and relatives (Yin and Sun Reference Yin and Yu2020). While activists have been lobbying for the criminalization of sexual harassment in China since the mid-1990s (Tang Reference Tang1995, Reference Tang2001),Footnote 18 anti–sexual harassment (ASH) gender lobbying is still ongoing, given that its primary legislative goal of a specific law defining and regulating sexual harassment as a criminal act has not yet been achieved.Footnote 19 Even though ASH activism has resulted in several articles spread out across three laws and two government regulations prohibiting sexual harassment, these articles only serve as general principles and lack clear definitions and evidence requirements to be practicable in lawsuits (Jiang Reference Jiang2006; Li and Dong Reference Li and Dong2004; Tang Reference Tang2001).

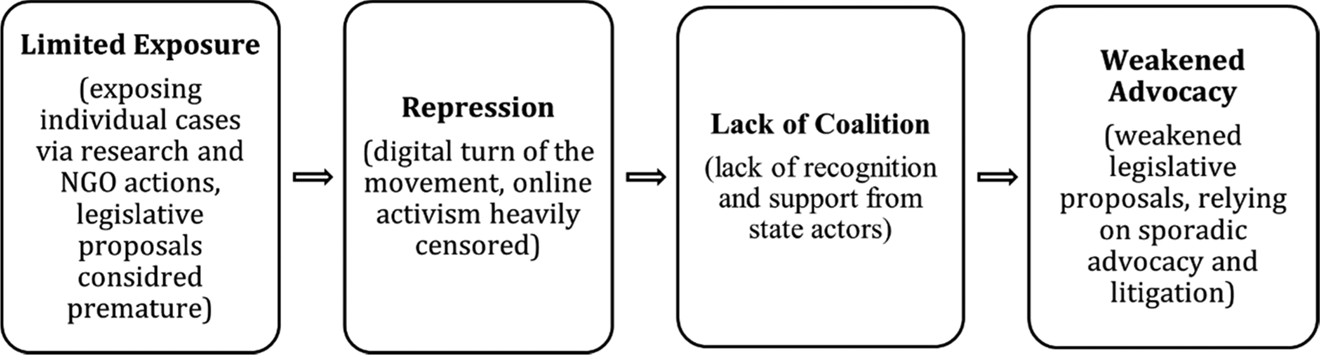

Compared with the ADV case, which went through the four-step mobilizing process of identification, crystallization, coalition, and proposal, the ASH gender lobbying distinguished itself in two respects: its limited exposure and thus lack of issue crystallization in the public sphere from the beginning, as well as state repression because of the political sensitivity of the issue. With its recent digital turn and engagement with an international movement, ASH activism has become a politically sensitive topic that has been heavily censored and subsequently received little support from potential allies within the state (see Figure 2). Together, ASH activists’ collective grievances were diluted and later turned into contentious collective action with limited political space to move forward.

Figure 2. Ongoing lobbying mechanism for anti–sexual harassment.

Limited Exposure

The first stage of China's ASH activism started in the mid-1990s and lasted until the 2010s, during which time a handful of researchers, lawyers, and legislators initiated lobbying and tried to expose the issue to the public. However, these attempts, combined with a limited number of reported sexual harassment cases, resulted in only limited exposure to the public (Pengpai News 2020).

In 1995, a researcher in China's Social Science Academy, Tang Can, published the first research report on sexual harassment, titled “The Existence of Sexual Harassment in China.” The report documented that 84% of 169 female respondents from Shanghai, Beijing, and Changsha had experienced sexual harassment (Tang Reference Tang1995). In parallel, the record of the Maple hotline showed that from 1992 to 2004, a total of 613 calls from women reported “sexual harassment.” Most of these cases occurred in the workplace, and 35% of them involved a superior and 15% colleagues (Sohu 2011). In 2001, for the first time in China's legal history, a female employee sued her employer for sexual harassment, demanding formal apologies and compensation. However, the local court rejected her accusation as there was no legal article appropriate for her case (Shen Reference Shen2004).

These events and records, although limited in number, spawned some media attention and legislative efforts (Feng Reference Feng2020). For instance, in March 1999, a member of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, Chen Kui Zun, with 32 other legislators, submitted a draft proposal of the Anti–Sexual Harassment Law in the People's Republic of China (Li Reference Li2000). However, Chen's proposal was refused. He explained later,

The Working Committee of Legislative Affairs gave us a reply, saying that: “it is very good for you to raise this issue. However, given that there are not too many judicial practices in this area, a process of accumulating experience is needed, and the legislation can be considered after the conditions have matured.” (Sina 2002)

Despite this legislative setback, researchers and women's groups continued to pressure for changes. For example, in 2003, a female professor at China University of Political Science and Law advocated for wider public acknowledgment of the prevalence of sexual harassment. In an interview, she underlined that

Although sexual harassment is so common and its impact is so severe, few people, especially women, really dare to stand up for justice. Most people swallow their anger in order to preserve their jobs and reputation. But this has rather contributed to the arrogance of the perpetuators. (cited in Wang Reference Wang2006)

Soon after that, in 2005, the ACWF cohosted the International Seminar on Anti–Sexual Harassment in Workplaces with the International Labour Organization. The seminar was attended by top leaders from women's groups, trade unions, legislative committees, and supreme courts and discussed various aspects of the issue of sexual harassment (Ma Reference Ma2005). According to Ma (Reference Ma2005), the participation of political elites in this seminar directly accounted for the inclusion of the term “sexual harassment” in the Amendment of the Law on the Protection of Women's Rights and Interests, which took place only several months later.

The initial efforts made by individual victims, intellectuals, NGOs, and legislators resulted in both progress and setbacks. At first glance, the initial stage of ASH activism shares many similarities with the ADV activism, especially by involving both Party-affiliated and nonstate actors. However, the number of sexual harassment cases reported to the WFs, police departments, and courts was limited because of the lack of positive responses and the strong social stigma regarding being a victim of sexual violence (Li Reference Li2014; Research Group 2009). Also, the discussions by legislators and women's organizations remained in their own organization and did not spawn a wider public discussion. These problems were augmented in the next stage, when the ASH movement took a digital turn; there, the lack of support from both the public and the state further diverted it from the successful coalition-based path taken by the ADV activism.

Digital Turn and Repression

When a few lawyers, academics, and NGOs continued in the 2000s and early 2010s to pressure for more practicable laws with clear definitions of employer liability and rules for punishing sexual harassment (Hu Reference Hu2006; Jiang Reference Jiang2006), a younger generation of feminists started using creative street demonstrations and digital media to engage with ASH activists in China's cosmopolitan cities. Footnote 20 For instance, in 2012, responding to a heated debate online over whether a girl's see-through dress should draw unwanted attention on the subway in Shanghai, two young feminists covered their faces and held signs reading “I can be slutty but you cannot molest me” (wo keyi sao, ni buneng rao) in subway stations to protest such victim-blaming discourses (Chen Reference Chen2012). However, amid a tightening political atmosphere, feminist activists engaging in street protests were soon detained, and offline feminist actions became less frequent (Zeng Reference Zeng2015).

Coinciding with the global #MeToo movement, young Chinese students and activists moved their ASH campaign online. Because of the academic and professional dependence of students on their supervisors, sexual harassment and assault on campuses is particularly prevalent (Li Reference Li2014; Zeng Reference Zeng, Fileborn and Loney-Howes2019). In 2018, a female academic, Luo Xixi, currently living in the United States, started China's #MeToo movement by revealing her experiences of being sexually harassed by her PhD supervisor at Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (Denyer and Wang Reference Denyer and Wang2018). Her detailed testimony on the popular online forum Weibo received millions of views and attracted thousands of supporters’ signatures demanding the resignation of the supervisor. Luo's experiences were soon echoed by many young women, especially those working in academia, NGOs, and journalism (Li Reference Li2014; Lin and Yang Reference Lin and Yang2019). For most online participants, the #MeToo movement served as a platform to share personal voices, educate peers, raise awareness of sexual harassment, and receive support; it also served as a means to counter patriarchal power and seek moral justice (Lin and Yang Reference Lin and Yang2019; Zhou and Qiu Reference Zhou and Qiu2020).

In March 2018, the low point of the ASH movement arrived when many posts and comments under the #MeToo hashtag were censored or deleted. A leading feminist media channel, Feminist Voices (Nüquan zhisheng), and its Weibo and WeChat accounts were also shut down by the National Security Department (Lin and Yang Reference Lin and Yang2019; Yin and Sun Reference Yin and Yu2020; Zeng Reference Zeng, Fileborn and Loney-Howes2019). Alongside the censoring of many other independent media engaging with ASH activists, this event symbolized the state's repression of the #MeToo movement as part of the long-lasting ASH gender lobbying effort in China.

Lack of Coalition and Weakened Advocacy

We identify the lack of coalition, coupled with the previous steps of limited exposure and repression, as a decisive mechanism that led to the stagnation of ASH activism in China. Like the case of ADV, the lobbying process for ASH involved a variety of actors. However, ASH activism failed to form a coalition: (1) victims were atomized instead of unified because of the lack of responsible authorities and the digital means of accusation; (2) engagement with the international #MeToo movement and broad online involvement turned ASH activism into a politically sensitive matter, one that state actors such as the WF were reluctant to get involved in. These features led the ASH activism to have very different lobbying tactics and results compared with the ADV.

Unlike the ADV activism, during which hundreds of victims in Hunan Province were organized by the WF as a unified body demanding action, ASH activism had fewer chances to unify victims. First, while the WF is officially responsible for domestic violence and serves as a central point for compiling information, those who are meant to respond to sexual harassment are the employers and work units, which are scattered. Oftentimes, victims tended to find that the responsible authorities—usually the employers of the perpetuators—neither mandated nor were willing to respond to their appeals in the name of protecting the institution's reputation (Li Reference Li2014; Research Group 2009). Second, in the latest phase of the #MeToo movement, female victims chose to publish their victimhood online, demanding justice instead of having their cases formally registered by the police and compiled at the local WF as empirical evidence for legislative proposals. These online posts were sporadic, censored, and failed to be formally recognized. These features also explain why, unlike the legislative efforts made by ASH activists in the early stage, individual-based advocacy and litigation became the new form of ASH gender lobbying after the digital turn and no new legislative proposal with significant political support was put forward.Footnote 21 The only institutional change demanded by the movement was to establish a nationwide mechanism to prevent sexual harassment in higher education (Feng Reference Feng2020). Obliged to respond to such popular demand, the Ministry of Education issued two professional codes for teachers, which, again, lack concrete implementation plans (Ministry of Education 2018a, 2018b).

ASH's inability to form a coalition was also attributable to the state's repression for crossing the political boundary of the CCP—in this case, the connection with international activism. The CCP has always been unclear about where the boundary of acceptable activism lies, and the boundary might change along with the leadership. In the case of ASH, many have sensed a change in the political climate since 2013, when more internationally funded NGOs were suspended or disassembled (Shieh Reference Shieh2018). Therefore, unlike during the ADV lobbying, when China needed to regain its international reputation by hosting the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, the Party-State has seen grassroots movements, especially those with international connections, as a sensitive and destablizing matter. Stricter political censorship of activists and online discussions of ASH not only created more barriers for the formation of collective demands, but also explain the inactivity of the WF, which severely limited the formation of strategic coalitions between state (i.e., legislators, lawyers, and WFs) and nonstate actors (i.e., NGOs and activists). As a provincial WF cadre explained,

Do you think this issue of sexual harassment itself is sensitive? I do not think so. Because victims have legitimate rights [to seek justice]. The problem is that this issue is an important concern of international organizations and is closely related to the international feminist movement, which made it a very sensitive issue [in China] [ . . . ] Solving the problem of sexual harassment in China is actually very convenient: reporting your case to the Municipal Commission for Discipline Inspection or the Supervisory Commission. But the problem is that this issue has not yet come to the point where [the legislation] is necessary. I think it has not become a problem that needs everyone to discuss and resolve it together; it may still have something to do with the awakening of women's awareness of power and the fact that women do not find it necessary to fight against it.Footnote 22

Although our argument underlines the importance of coalition-based lobbying, the prolonged ASH activism in China is also explained by its innate characteristics. First, some lawyers and WF cadres have argued that the nature of sexual harassment makes it inherently more complicated to tackle, both socially and legally. They have, for instance, underlined that sexual harassment is considered to cause less fatal damage than other offenses, as no one's life is under threat.Footnote 23 Also, as explained by Wen, a lawyer who specializes in the domain of marriage and family, the perpetuators of sexual harassment are often power holders in public spheres such as universities and workplaces, which makes ASH inherently more challenging than ADV.Footnote 24 In addition, ASH activism, especially in its last stage, also lacked wider coalitions among different women's groups. While the digital turn of ASH activism has led to the celebration of anonymity, it has also led the ASH movement to be more exclusive, with little participation by rural women or other subaltern groups (Yin and Sun 2019; Zeng Reference Zeng, Fileborn and Loney-Howes2019). The isolated nature of its grievance, the digital means of activism, and the international connections of ASH activism have added to the difficulty of compiling a large number of cases and forming coalitions to further problematize the issue of sexual harassment.

CONCLUSION

While past research has investigated the link between women's descriptive and substantive representation, especially in legislative bodies, this study shows that studying the number female legislators might not be enough to understand substantive representation in China (Sargeson and Jacka Reference Sargeson and Jacka2017). Both our cases show that tracing gender lobbying processes from the beginning offers much more insight. This is especially important in an authoritarian regime where, as Truex (Reference Truex2020) recounted, there are few players with vetoes and fewer voices at the table. In other words, the most critical step for legislation is bringing the proposal to the floor rather than voting on and passing a law (Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). With a comparative study of the ADV and ASH cases, we show that when examining the process of WSR in a given political context, three factors are of critical importance: (1) the definition of women's interests, (2) the mapping of actors and institutions, and (3) the tracing of gender lobbying mechanisms.

First, who defines women's interests and their incentives is equally important, as they shape the gender lobbying mechanism and decide what issues are safe to lobby on. In the Chinese case, motivated by ideological and political legitimacy at both the domestic and international level, legislation concerning women's rights is overidealized and dogmatic, which prevents any gender proposals that are politically sensitive and deviate from existing gender agendas monitored by the CCP from entering the legislative processes.

Second, this article shows that in a nondemocratic political context, WSR often relies heavily on the intertwining of institutional sites and actors in collective gender lobbying attempts. Cooperation between state and nonstate actors, while not uncommon, has a different shape in China. Nonstate actors have to adopt cooperative or even dependent, rather than oppositional, relationships with state actors to survive, which directly determines their lobbying strategy. Similarly, when women's policy machinery is marginalized with weak political clout, femocrats take advantage of the CCP's fusion of power and personnel and utilize personal connections outside of the legislature to power through.

Third, this article pays particular attention to the comparison of gender lobbying mechanisms in the two selected cases to explain the conditions under which WSR is more likely to happen. The compilation of a significant number of cases, especially if recorded by a public authority, proves to be the key to forming collective grievances and starting the lobbying process. Successful lobbying also requires the support and recognition of the public, as well as a “timely” shock to public opinion, otherwise a legislative proposal might be deemed premature. Most importantly, gender lobbying needs to form strategic alliances with actors from within the state, including lawyers, female and male legislators, and officials, who can turn the sporadic media reports and local protests into well-received and substantial legislative proposals. Such a coalition is difficult to achieve and the role of international influence is decisive yet ambivalent: on the one hand, as shown in the ADV case, international funding and norm diffusion can bring in new agendas, theories, and resources to sponsor China's domestic gender lobbying processes; on the other hand, as observed in the ASH case, strong influence from international movements can also lead to the political sensitivity of an originally “neutral” topic and absence of support from key state actors. Even when the lobbying received collective support from nonstate feminist groups, such support might quickly become “sensitized” by the authority, fearing that the mobilization could lead to social unrest and challenge the authority.

In sum, by reviewing the key steps of two different gender lobbying cases in contemporary China, our article argues that a coalition-based gender lobbying process, involving both state and nonstate actors and legislative and executive institutions, serves as a key for WSR in authoritarian regimes. However, it is also important to notice that both cases reveal a fundamental challenge of gender lobbying in the Chinese context: what happens when the political authorities do not agree with the content or means of gender activism? China's socialist past has given privilege to its Party-sponsored women's organizations to advocate for WSR. However, a new generation of feminists, growing up in a liberalized and globalized era and influenced by global feminist movements, might not agree with these state-defined “women's interests” and prefer to advocate for their own feminist agendas. In this sense, the lack of coalition with state actors is not necessarily a strategic failure, but an intended positioning that adopts a counterhegemonic standpoint against the authoritarian state power, which should be seen as part of the feminist rebellion instead of a shortcoming.