Since the end of the Bretton Woods order, financial crises have become increasingly ubiquitous fixtures in the global economic system. More than 1,600 financial crises have occurred since 1976 (Reinhart and Rogoff Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2009), including inflation crises, currency crashes, sovereign debt crises and banking crises. Crises have tremendous impact; they destabilize economies, instigate political instability, and pose immediate and longer-term threats to personal well-being (Blanton, Blanton and Peksen Reference Blanton, Blanton and Peksen2015a; Serieux et al. Reference Serieux, Munthali, Sepehri and White2012). Ordinary citizens feel the economic damage caused by financial instability directly through diminished employment (Choudhry, Marelli, and Signorelli Reference Choudhry, Marelli and Signorelli2012) and reduced state spending in such areas as housing, food assistance, health, and education (i.e., Mohindra, Labonté, and Spitzer Reference Mohindra, Labonté and Spitzer2011; Sirieux et al. Reference Serieux, Munthali, Sepehri and White2012). Problems often persist even after the crisis ebbs; firms are often slow to hire again and government revenues tend to remain stagnant (Bernal-Verdugo et al. Reference Bernal-Verdugo, Furceri and Guillaume2013).

Given the frequency of crises as well as their impact on the global economy, a great deal of research has focused on their causes and consequences. Yet many aspects of these crises remain poorly understood and empirically underexamined. There are many “underexplored gendered elements of economic crisis” (Kushi and McManis Reference Kushi and McManus2018, 458), particularly in areas that do not relate to purely economic outcomes such as employment. Moreover, extant literature on gender and financial crises, much like the broader body of literature on the impact of financial crises, consists largely of studies of either individual countries or one specific type of financial crisis. Indeed, surprisingly few studies assess the consequences of financial crises in a comprehensive and systematic manner. Although any given crisis may have idiosyncratic factors, it is also worthwhile to examine common patterns across crises because “one may also expect to observe similar commonalities in human and social consequences of financial crises across countries at different stages of economic development” (Mohseni-Cheraghlou Reference Mohseni-Cheraghlou2016, 89).

In our analysis, we examined the extent to which banking crises, currency crises, domestic sovereign debt crises, external sovereign debt crises, and inflation crises affect women's share in the total labor force, their access to education, health, and political representation. Although these aspects of women's status are certainly related, we expected to find that financial crises affect their dynamics in distinct ways.Footnote 1 We hypothesized that crises are particularly damaging to female employment due to the precarious place of women in the formal labor force as well as the common view of female labor as less “essential.” Reduced state spending, which often occurs in the aftermath of financial crises, is particularly detrimental to female health and educational outcomes. Financial crises also hurt women's political representation because they constrict women's involvement in politics as well as the demand for female candidates.

In this analysis, we examined the consequences of financial crises for our measures of women's well-being across 68 countries for the years 1980–2010. Since the impact of crises often prove persistent, we next assessed the extent to which these effects continue for a seven-year period after crises end. We identified a significant and negative relationship between each of our measures and financial crises, indicating that crises have a deleterious effect on women's economic and political well-being as well as their health conditions and access to education. Moreover, the gendered impact of crises were somewhat stronger three years after the crisis and persisted up to seven years after the end of the crisis. Thus, financial crises threaten multiple facets of women's well-being, and the effects of crises persist after a crisis subsides.

GENDER AND FINANCIAL CRISES

Financial crises have widespread effects that reverberate throughout societies, although extant literature notes that they are particularly detrimental for vulnerable populations (e.g., Cutler et al. Reference Cutler, Knaul, Lozano, Mendez and Zurita2002; Signorelli, Choudhry, and Marelli Reference Signorelli, Choudhry and Marelli2012; Stavropoulou and Jones 2013). Women are often one of the most vulnerable groups. Even in the best of times, “women hold fewer assets, earn less, own a fraction of the world's enterprises, and are often denied more opportunities than men, even when they have the same or higher level of education” (Calardo Reference Calardo2017). When financial crises strike, the ensuing economic downturn may exacerbate economic and political inequalities because costs are “borne disproportionately by women” (Floro and Dymski Reference Floro and Dymski2000, 1269). Given the multiple ways that women bear these costs, we focused our analysis on possible effects of financial crises on women's employment in the formal workplace, access to education, health, and political representation.

Consequences for Female Labor

Extant studies delineate several ways in which financial crises constrain economic opportunities for women, particularly within the formal sector. First, the gendered structure of the labor force and the economy, particularly in the developing world, lends itself to men and women facing different levels of vulnerability to financial shocks. Men generally work in greater numbers in industrial sectors and financial business services, which tend to offer better-paying jobs. Women are more likely to seek “vulnerable employment” (ILO 2008), including work in the services, agriculture, textile, or low-end manufacturing sectors (Antonopoulos Reference Antonopoulos2009). Given this structure, women may find themselves harder hit by economic downturns, which can exacerbate the vulnerabilities evident in these sectors and push women out of the formal labor pool (King and Sweetman Reference King and Sweetman2010; Walby Reference Walby2009).

Employer perceptions of female labor exacerbate these structural disadvantages. The “basic labour market vulnerabilities of women (are) … reinforced by sexist attitudes on the part of employers who regard women as secondary income earners and have used this as a pretext for dismissing them first when their enterprises experience difficulties” (Singh and Zammit Reference Singh and Zammit2000, 1260; see also ILO 1999; Kushi and McManus Reference Kushi and McManus2018). Women are thus less likely to be hired, and more likely to be fired arbitrarily, than men, even from low-skill and low-wage jobs (Aslanbeigui and Summerfield Reference Aslanbeigui and Summerfield2001; Benería Reference Benería1995). Financial crises, during which employers eliminate jobs or reduce employment benefits, aggravate these problems. Employers often lay off women in disproportionate numbers during these times, as shown by multiple studies of financial crises in Europe, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean (e.g., Floro and Dymski Reference Floro and Dymski2000; King and Sweetman Reference King and Sweetman2010; Kushi and McManus Reference Kushi and McManus2018). Furthermore, female job seekers will likely find it difficult to secure jobs in traditionally male-dominated sectors, and they may be forced to defer to men who are seeking employment. In short, in times of crisis, women may be the first employees fired and the last ones hired, which subsequently results in less female participation in the total labor force.

At the same time, financial crises bring to a head the paradoxical position of women within the household. Commonly viewed as dispensable in the labor force, women's employment is frequently a lower priority. Even in developed countries, there is “strong public support of the idea that men have more of a right to jobs than women during times of high unemployment” (Kushi and McManus Reference Kushi and McManus2018, 457). At the same time, women are “indispensable as surrogates for the social safety net” within their households (Aslanbeigui and Summerfield Reference Aslanbeigui and Summerfield2001, 14). That is, while many societies expect men to be the primary economic contributors outside of the home (Benería Reference Benería2003; Detraz and Peksen Reference Detraz and Peksen2016), women are expected to ensure the welfare of their families and are primarily responsible for child care, elder care, and other household duties.

During crises, families must often adjust to cope with the economic downturn. This can have a significant impact upon women, who commonly take on additional responsibilities to help their families stay afloat, such as caring for sick family members and searching for less expensive food, water, and other staples (Antonopoulos Reference Antonopoulos2009; Singh and Zammit Reference Singh and Zammit2000). Considering these factors together, while crises incentivize female participation in the work force to shore up declining family incomes (Parrado and Zenteno Reference Parrado and Zenteno2001), the increased workload within the family may reduce female opportunities to gain employment within the formal sector. These intrafamily dynamics can exacerbate the disadvantages women already face in seeking work.

Taken as a whole, these linkages led to our first hypothesis:

H1:

Financial crises lead to decreases in women's representation in the formal labor force.

Consequences for Women's Political Representation

Financial crises might also have significant implications for women's political participation. Gender issues figured prominently in many analyses of the 2008 financial crisis. Some argued that the crisis represented the “death of macho,” and predicted a “monumental shift in power to women” (Salam Reference Salam2009, 65) in response to the abuses of a male-dominated financial sector that incentivized risky behaviors that precipitated the crisis (Prügl Reference Prügl2012). Ostensibly, the economic damage associated with a financial crisis, such as job loss or home foreclosures, could create demand for more compassionate leadership, which would thus give women an electoral advantage. For example, Iceland and Lithuania, two countries hit particularly hard by the crisis, elected female prime ministers for the first time in their countries’ histories, with a Lithuanian newspaper declaring, “the country is to be saved by a woman” (Salem 2009, 66). Yet the overall impact of the crisis upon female leadership was more equivocal in practice. Even within Europe, women lost ground in several other crisis-stricken countries, including Estonia, Portugal and Spain (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2011, 5). We hypothesized that the popular conception of the 2008 financial crisis may have been somewhat of an outlier and that financial crises may have a negative impact upon women's political involvement, particularly their ability to gain elected office.

Female political representation is commonly viewed in terms of the “supply” of female candidates and the “demand” of the voters for female candidates (Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003). Financial crises affect both supply and demand to the detriment of female representation. The adverse economic and education effects discussed herein shape supply factors. Specifically, the pool of prospective female candidates is generally drawn from “educated women … and professionals in their mid-thirties onward” (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2000, 96–97). The presence of such a pool presupposes access to educational opportunities as well as the ability to obtain some degree of professional stature and advancement in the formal workforce. Moreover, professional and educational attainment presumes some modicum of economic resources. At the very least, given the time and resource demands of mounting a political campaign, it becomes harder for people with economic insecurity to take an active role in politics (Berg-Schlosser and Kersting Reference Berg-Schlosser and Kersting2003; Detraz and Peksen Reference Detraz and Peksen2018). Education and employment are also useful in enabling women to develop a necessary constituent base, political contacts to facilitate viable campaigns, as well as knowledge and experience related to issues important to their constituents (Peksen and Detraz, Reference Detraz and Peksen2017; Shvedova Reference Shvedova, Ballington and Karam2005). As crises limit economic and other opportunities, we expected the potential supply of female candidates for office to be lower in countries undergoing major financial hardships.

On the demand side, extant work on gendered voting provides insight about the prospective impact of financial crises on voter support for female candidates. First, issue salience matters. Males are more likely to be supported in dealing with issues that are viewed as “salient,” whereas females are viewed as more capable of dealing with issues that are viewed as “less critical” (Falk and Kenski Reference Falk and Kenski2006, 3; see also Deloitte and Touche Reference Deloitte and Touche2000). For example, gender stereotypes are particularly prominent in national security issues because men are “perceived as more competent in running the military and attending to national security” (Schroeder Reference Schroeder2017, 568). When these issues are viewed as important by the public, female candidates “will have greater difficulty convincing voters they can maintain security because of the widely held stereotypes about women's innate abilities” (Schroeder Reference Schroeder2017, 568; see also Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016; Lawless Reference Lawless2004). Specifically, voters perceive men as being “more assertive, stronger leaders” (Holman et al. Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016, 135), with women viewed as more “compassionate” and thus better suited for dealing with issues such as poverty, education, and family care (Bauer Reference Bauer2015; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993).

Similar dynamics may be apparent in voter responses to financial crises. Finance and “big business” concerns are perceived as part of the male domain, and men may be viewed as better suited for dealing with these issues (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). Although some economic policy issues, such as social spending, may be viewed more as “compassion” issues, voters may view economic crises differently. Specifically, crises are readily framed as disasters or threats, and they are often described in terms akin to military conflict. For example, in defending his response to the 2008 financial crisis, former U.S. Treasury Security Henry Paulson cited the need to “act decisively” against the “prospect of imminent economic catastrophe” (Paulson Reference Paulson2013, 3). Timothy Geithner, Paulson's successor, described his first tasks as defusing “financial bombs” (Geithner Reference Geithner2015, 4) created by the crisis. Pushing the conflict metaphor further, Mahathir Bin Mohamad, former Prime Minister of Malaysia, likened his country's financial crisis to a losing “war” against foreign invaders, in this case, global capital markets and financial institutions. “In the old days you needed to conquer a country with military force, and then you could control that country. Today it is not necessary at all.” Rather, financial crises can “destabilize a country, make it poor” and force them into dealing with institutions that have effectively “colonized that country” (Yergin and Stanislaw Reference Yergin and Stanislaw2002).

Viewed along these lines, a financial crisis might encourage voters to value the strength, assertiveness, and aggressiveness more commonly associated with males (Lei and Bodenhausen Reference Lei and Bodenhausen2018). Voters might perceive financial crises similar to national security crises, as a threat requiring a strong and decisive response rather than a “compassion” issue. Thus, crises might reduce both the supply of and the demand for female candidates. This brings us to our second hypothesis:

H2:

Financial crises reduce female representation in elected office.

Consequences for Women's Health and Access to Education

Compared to the economic consequences of financial crises, far less research is available on the impact of crises on women's health and educational attainment. Relatively speaking, “We know little about the specific channels through which financial crises can harm various dimensions of human and social well-being” (e.g., Mohseni-Cheraghlou Reference Mohseni-Cheraghlou2016, 88) and even less about the gendered nature of these effects. However, extant literature provides some expectations for the health and education effects of financial crises on women.

A relatively consistent finding is that countries undergoing financial crises commonly reduce government spending (e.g., Mohindra et al. Reference Mohindra, Labonté and Spitzer2011; Sirieux et al. Reference Serieux, Munthali, Sepehri and White2012), with “declines in the growth rates of health and educational expenditures, (and) government welfare expenditures” (Mohseni-Cheraghlou Reference Mohseni-Cheraghlou2016, 88). Reduced investment in the public sector and support services often undermines the coping mechanisms of families and communities and aggravates the “social and economic vulnerabilities of both poor and middle-class households” (Floro and Dymski Reference Floro and Dymski2000, 1271). Although these cuts affect entire households, their ultimate impact is gendered because reductions in such social spending as government-funded health and education programs have a more substantial negative impact on women (Walby Reference Walby2009). Women have greater need of investment in health care given that they are “more likely to be poor and out of the cash nexus and have more health-care needs due to pregnancy” (Aslanbeigui and Summerfield Reference Aslanbeigui and Summerfield2001, 13–14). This basic disparity might be exacerbated at the household level. As resources for health care become increasingly scarce, needs of male family members are typically “prioritized in the process of rationing household resources to the detriment of girls and women” (Mohindra et al. Reference Mohindra, Labonté and Spitzer2011, 276; Iyer, Sen, and George Reference Iyer, Sen and George2007). Because of this “rationing bias,” women, particularly those from poor households, may simply discontinue treatments or health services. Multiple studies of crises in Asia and Latin America find that women and girls “carried the brunt of the costs” (Aslanbeigui and Summerfield Reference Aslanbeigui and Summerfield2001, 13) of reduced government investment in human capital, including reduced investment in health (Mohindra et al. Reference Mohindra, Labonté and Spitzer2011).

The same dynamic is apparent in education, as “rationing” at the family level exacerbates the impact of cuts in public spending on education. To many families undergoing financial hardship, the “future benefits to educating sons may be perceived to be higher than to educating daughters, making it attractive to pull girls out of school during crises” (Sabarwal Reference Sabarwal, Sinha and Buvinic2010, 6; see also Rose Reference Rose1995). Put another way, removing female children from school, and often placing them into the informal workforce, may function as a “coping strategy” (Buvinic Reference Buvinic2009, 3) for poor households in developing countries. Extant case studies suggest that the impact of crises on education may be particularly acute in lower-income countries, where child labor is seen as a more viable strategy to increase household incomes. Such patterns have been evident in Costa Rica, the Philippines, and Indonesia, where economic downturns were related to increases in child labor and female work hours and to decreased female enrollment in school (Jensen Reference Jensen2000; Lim Reference Lim2000). Furthermore, crises-driven gender gaps in education might be more prevalent among older girls (above the age of 15) because they face greater pressure to enter the workforce then their younger counterparts (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Beegle, Frankenberg, Strauss, Sikoki and Teruel2004). These data led us to our third and fourth hypotheses:

H 3:

Financial crises negatively affect female health outcomes.

H 4:

Financial crises negatively affect women's representation in tertiary education.

Lingering Effects of Financial Crises on Women

The longer-term effects of financial crises are also of interest because we could not assume that the negative effects dissipate quickly or that states would return to their precrisis conditions. For example, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the economic concept of “hysteresis” regained prominence. Briefly, traditional macroeconomic theory predicts that economic shocks (e.g., financial crises) are followed by “a recovery period in which output returns to potential,” and that in the long run, “potential itself is not affected significantly” (Ball Reference Ball2014a, 149). By contrast, the logic behind hysteresis is that short-term downturns can also hamper longer-term prospects and leave lasting effects on economies. For instance, when short-term unemployment persists, unemployed workers may lose key skills while they are out of the workforce and thus never recoup the productivity losses. The central problem here is that the underlying factors that drive longer-term growth may also suffer, and as a result, an economy does not return to precrisis levels of productivity but faces a “new normal” of lower levels of employment and output (Ball Reference Ball2014b; see also Blanchard and Summers Reference Blanchard and Summers1986; Fatás and Summers Reference Fatás and Summers2016). Along these lines, studies of the effects of the 2008 financial crisis have found that economies in the developed world have remained far below the potential levels predicted by their precrisis performance (Ball Reference Ball2014a; Fatás and Summers Reference Fatás and Summers2016).

Political science theories, particularly historical institutionalism, have predicted somewhat similar dynamics, namely the idea that certain events might represent “formative moments” that can produce lasting changes (Peters, Pierre, and King Reference Peters, Pierre and King2005; see also Hall and Taylor Reference Hall and Taylor1996), particularly if they call into question existing practices or institutions. Financial crises can constitute such “moments” because they may substantially alter the institutional context of a state, potentially creating new balances of political power within systems. Indeed, crises commonly precipitate regime change or sweeping political reform (Engelen Reference Engelen2011; Haggard Reference Haggard2000). Such changes may have lasting political impact. For example, Blanton et al. (Reference Blanton, Blanton and Peksen2015a) found that financial crises disrupted the balance of power among capital, labor, and the state to the detriment of labor and that the negative impact of financial crises on labor rights were still apparent five years after the crisis occurred.

The gendered impact of crises on women's well-being might also be expected to persist. Economically, given the treatment of females in the labor force, particularly their low priority in relation to male workers, employers may prioritize male employees in the rehiring process. Just as women may be the first out of a job, they may also be the last to return (Ghosh Reference Ghosh2010; Seguino Reference Seguino2010). Similarly, we anticipated that the impact of public spending cuts would only worsen in the long term and that the negative results on the reduced investment in female education and health care would fully take hold over subsequent years. Finally, we expected that the impact of crises on female political representation would also prove persistent, given the nature of election cycles as well as the fact that any disruption in the “pipeline” in prospective candidates would take time to overcome. Time and effort are required for female candidates to develop the resources and connections necessary to (re)enter politics. Thus, we anticipated that the negative impact of financial crises on women's well-being would persist even after the crisis subsided and that women would face a “new normal” of reduced opportunities.

DATA AND METHODOLOGICAL SPECIFICATIONS

To analyze statistically the possible effect of financial crises on women's well-being, we gathered time-series cross-sectional data for the period 1980–2010. Our unit of analysis was the country year, and the sample included 68 countries for which financial crises data were fully available from Reinhart and Rogoff (Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2009; Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2011). Crises have occurred across a diverse grouping of countries, and the sample included countries at all stages of development and across all geographic areas of the world. However, our data were unbalanced due to varied data availability across the different outcome measures; thus, the sample size varied slightly across the models. Descriptive statistics for all the variables and the list of countries included in the analysis appear in the online appendix (Tables A1 and A2).

Outcome Variables

We used four different outcome variables to capture different dimensions of women's well-being. Female labor force participation measures the proportion of the total labor force that is female. This metric is commonly used to capture the extent of female participation among the economically active population, specifically the formal economy (Sabarwal et al. Reference Sabarwal, Sinha and Buvinic2010).Footnote 2 In our sample, the measure ranged from 11.7% in Algeria to just greater than 50% in Ghana, with the former indicating a labor force with a very small proportion of females to males and the latter signifying a formal labor force split evenly between males and females. Labor force data were obtained from the World Development Indicators (World Bank 2016).

To measure the impact of financial crises on women's political participation, we included data on women's participation in national parliaments. This metric represents the proportion of seats held by women in unicameral parliaments or in the lower chamber in bicameral parliaments. In our sample, percentages ranged from 0 (no female parliamentarians, which was the case in multiple countries) to 47.3% in Sweden, which approximates parity in male and female representation in parliament. The female parliamentarian data were obtained from two different data sources: the World Development Indicators (World Bank 2016) and Women in National Parliaments (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2013) databases. Although these data capture only one facet of women's political participation, this proxy is frequently used because it shows the ultimate outcome of both the “supply” of female candidates as well as public “demand” for such candidates.

To analyze the impact of financial crises on female educational achievements, we included female tertiary education to measure the proportion of all tertiary students (i.e., both female and male students) who were women. Across the sample of states covered in this analysis, this measure ranged from 5.9% in the Central African Republic, which connoted a student body made up almost exclusively of males, to just greater than 66% in Uruguay, which indicated that females comprised roughly two-thirds of the total students at the tertiary level. This metric is particularly advantageous for our purposes in that relatively older girls are more likely to be pulled out of school due to crises (Lim Reference Lim2000; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Beegle, Frankenberg, Strauss, Sikoki and Teruel2004). Tertiary education data were obtained from the UNESCO cross-national database on education (2013).

To examine the extent to which financial crises might undermine women's health, we used the natural log of maternal mortality ratio, which accounts for maternal mortality rate per 100,000 live births.Footnote 3 The data for maternal mortality ratio were obtained from the World Development Indicators database. We restricted the model estimated with the mortality variable to the 1990–2010 period because the mortality data were missing in the database for most country years before 1990. For our purposes, the mortality and tertiary education measures were particularly useful because they provide insight into the effects of crises for women's health and education outcomes, which include more direct information than measures such as government spending.

Explanatory Variables

Our analysis included five major types of financial crises. Banking crises involve bank runs or other economic triggers that necessitate significant government intervention into the banking sector, including government seizure of financial institutions or at least widespread government assistance. Currency crises occur when a given currency depreciates at least 15% annually against the dollar or another major anchor currency (e.g., the euro). Sovereign debt crises occur when a country fails to make a principal or interest payment by the scheduled date. Sovereign debt crises are categorized as either external or internal depending on whether the debt is owed to foreign or domestic lenders. Finally, inflation crises are characterized by an annual inflation rate of at least 20%.

We operationalized financial crises in two ways.Footnote 4Financial crisis (presence) was coded one for the years a country faced any type of crisis and zero otherwise. However, although any single type of crisis connotes a major economic shock, multiple types of crises may occur simultaneously. For example, at the onset of the Asian financial crisis in 1998, Indonesia went through all five types of crises, while Russia went through four of the five types of crises in 1999. We thus included a second proxy, financial crises (total), to account for the number of different financial crises a country faced in a given year. This measure ranged from zero (no crisis) to five (all crises present) and had a mean value just less than one. In our sample, banking crises took place in 411 country years, while currency crises occurred in 437 country years, domestic debt crises occurred in 94 country years, external debt crises occurred in 418 country years, and inflation crises occurred in 378 country years.

We also include the natural log of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita to control the possible positive effect of economic prosperity on women. Higher levels of economic development might be positively related to women's well-being because women might have more opportunities to gain economic independence, personal autonomy, and socio-economic empowerment in wealthier societies (Duflo Reference Duflo2012). We also included the CEDAW ratification variable in the model to control for the possible positive effect of the ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Earlier research includes evidence that countries that ratified the CEDAW are less likely to tolerate systematic socio-economic and political discrimination against women (Cole Reference Cole2012). In this study, CEDAW ratification was a binary variable coded one in all the years since its ratification and zero otherwise. We also controlled for female population, an indication of the percentage of women in the total population, which accounts for the possibility that a relatively higher proportion of women in the total population might enable women to become more actively involved in the economy and politics.

Democratically elected leaders are more likely to enforce existing women's rights laws and to prevent systematic gender-based discrimination because they are more accountable to their citizens, they are concerned with the possibility of losing office through elections, and they are constrained by systems of checks and balances. Hence, women on average might enjoy better quality of life in democratic regimes than nondemocratic ones (Beer Reference Beer2009; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2001; Poe et al. Reference Poe, Tate and Keith1999). We controlled for this aspect using the democracy variable from the Polity IV dataset (Marshall, Jaggers, and Gurr Reference Marshall, Jaggers and Gurr2012). This measure ranges from –10 to +10, with higher scores indicating a more democratic regime in a given year.

We added economic openness to the model to account for the possible impact of global economic integration on women's well-being. This variable is the natural log of total trade volumes (exports and imports) as a percentage of GDP. Previous work on the gendered consequences of economic globalization notes that more economic openness might lead to improved living conditions for women and female empowerment through increased economic growth and wealth (Gray, Kittilson, and Sandholtz Reference Gray, Kittilson and Sandholtz2006; Neumayer and de Soysa Reference Neumayer and de Soysa2007). We obtained data regarding economic development, trade, and female population from the World Development Indicators database (World Bank 2016).

We also included the initial value of the outcome variables in the model. that is, the value during 1980 or the first year during which the data were available for female labor, political participation, and education outcomes, and during 1990 or the first year during which the data were available for the maternal mortality outcome variable. These variables specifically accounted for possible reversion-to-the-mean effects; the treatment of women is somewhat path-dependent and countries with relatively poor treatment of women in their recent history are less likely to experience a major change in their current treatment of women.

Given the continuous nature of the dependent variables, we used time-series ordinary least squares regression. Our analysis includes both fixed- and random-effects models. In addition to the methodological reasons for using a fixed-effects method, namely avoiding missing variable bias due to unit-specific effects that might not be captured by other variables, our use of both fixed- and random-effects models added substantive richness to our findings. Specifically, it facilitated insights into both the within-country effects of crises (i.e., how a crisis effects women's well-being within a given country) and between-country effects (i.e., how crises on average impact women's well-being across countries). We lagged all the time-variant explanatory variables one year (t − 1) to reduce the simultaneity bias and to ensure that they preceded the outcome measures by at least one full year.

FINDINGS

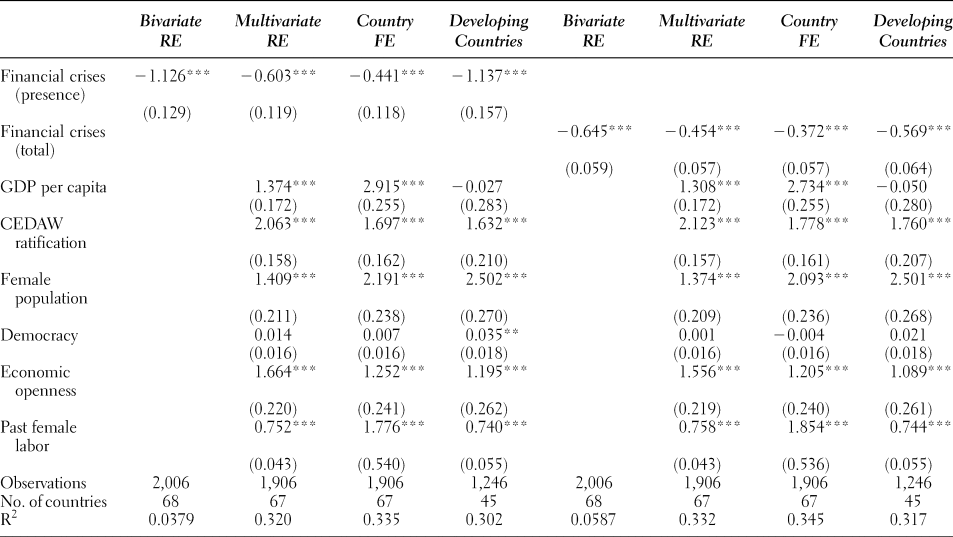

Table 1 reports the models on the impact of financial crises on the proportion of female participation in the total labor force. This table, as well as the subsequent ones, includes both random-effects and country fixed-effects models. We also present the results from the models restricted to developing countries (i.e., emerging or developing economies) as defined by the International Monetary Fund's World Economic Outlook Database (2016). Developed countries are less likely to experience financial crises, and women, on average, tend to enjoy better socio-economic and political conditions in the developed word. Thus, we excluded developed countries to determine whether their inclusion in the global models biased the results.

Table 1. Financial crises and women's economic well-being, 1980–2010: Female labor force participation

Notes: Standard errors appear in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. All time-variant explanatory variables were lagged at t − 1.

Our results are statistically significant and consistent across all the models in Table 1. The results in the first four models indicate that the presence of financial crises is likely to have a negative effect on women's participation in the labor force because it is linked to a reduction in the proportion of female labor in the formal labor market. The significance of the findings across both random- and fixed-effects models shows that these effects are apparent both within and between countries. Financial crises are not only related to lower female employment levels within countries. Countries experiencing financial crises, on average, also have lower levels of female employment relative to males. The results in the other models further confirm the hypothesized negative effect of financial crises by indicating that the higher the number of financial crises, the lower the proportion of female participation in the formal workforce. Overall, our findings offer robust support for the hypothesis that financial crises are significantly associated with relatively fewer females in the formal labor force (Table 1).

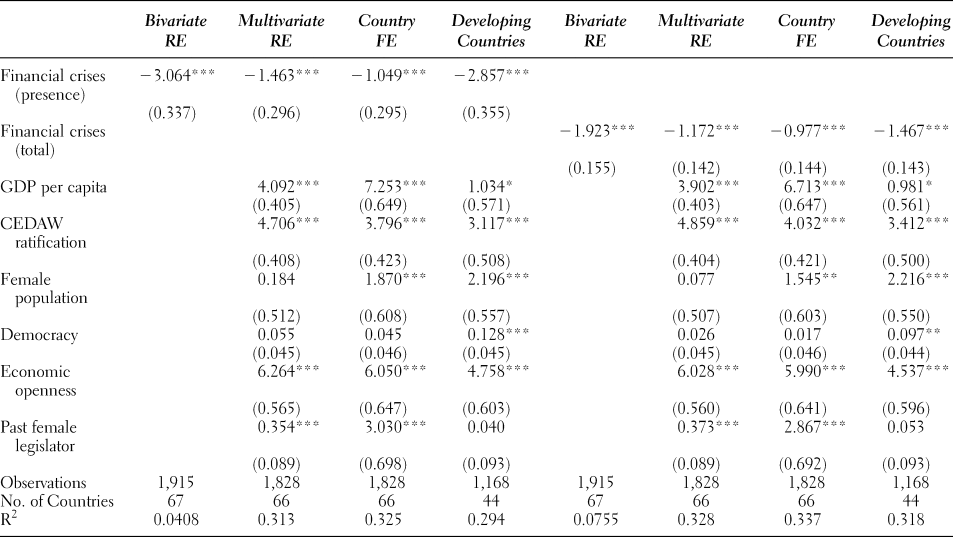

We examined the impact of crises on women's political empowerment, as measured by their representation in parliament (Table 2). We found significant and consistent support for our hypotheses that both the occurrence of financial crises, as well as the total number of crises a state is experiencing, reduce the proportion of women serving in parliament. These findings suggest that crises constrict both the “supply” as well as the “demand” for female candidates, and thus undermine women's ability to play an active role in politics.

Table 2. Financial crises and women's political status, 1980–2010: Women's participation in national parliaments

Notes: Standard errors appear in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. All time-variant explanatory variables are lagged at t − 1.

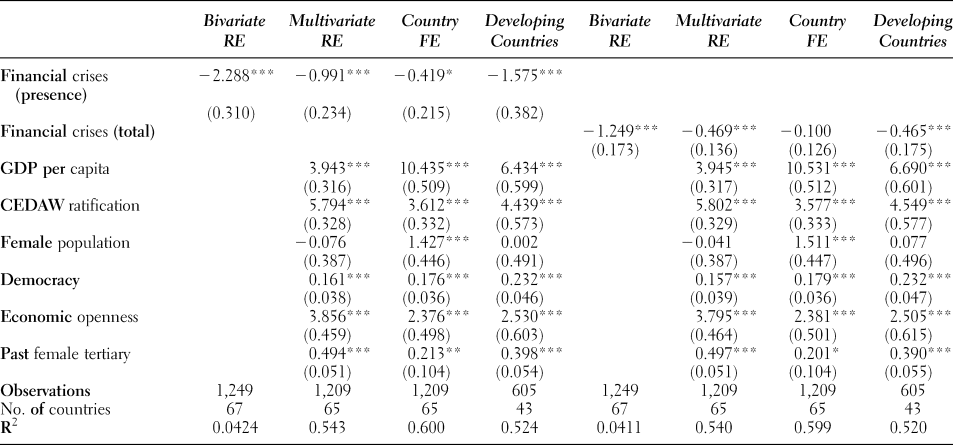

Table 3 shows the impact of financial crises on women's education, specifically female tertiary education. The results from the models suggest that both presence and number of financial crises are negatively associated with women's educational achievement relative to men across both our entire sample as well as the developing countries. Thus, we found support for the hypothesis that female education suffers more from the adverse socio-economic effects associated with financial crises, specifically at the tertiary level.

Table 3. Financial crises and female education, 1980−2010: Female tertiary education

Notes: Standard errors appear in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. All time-variant explanatory variables are lagged at t − 1.

We report the models for maternal mortality rate in Table 4. Once again, we found significant evidence across the models that crises are likely to be detrimental to a facet of female well-being, in this case women's health outcomes. Therefore, consistent with our theoretical expectations, our results indicate that women might not only face difficulties in access to politics, economic empowerment, and education but also diminish their physical well-being because they are less likely to have adequate access to health products and services.

Table 4. Financial crises and women's health, 1990–2010: Maternal mortality rate

Notes: Standard errors appear in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. All time-variant explanatory variables are lagged at t − 1.

What is the magnitude of the hypothesized effect of financial crises on women's well-being? Using global random-effects models that included the variable for the number of financial crises, we modeled the change in the predicted values of the outcome variables when the financial crises measure varied from its minimum (0 crises) to maximum (5 crises) scores, while holding the other continuous explanatory variables at their mean scores and the dichotomous variables at their median values in the models. In Figure 1, the upper-left panel shows the results for female labor force participation. The predicted value of women's share in the total labor force decreases from 39.3% to 38.9% in countries that experience any one of the five financial crises and from 39.3% to 37.05% in countries that face all five crises types in a given year. Substantively, this decrease is significant; the presence of multiple crises is associated with an approximately 6% decrease in female employment levels relative to males. Hypothetically, then, in a country with 10 million female workers in the formal workforce, 100,000 fewer female workers would be employed in the labor force if that country experiences a financial crisis, and 600,000 fewer female workers would be employed if that country experiences all five financial crises in a given year.

Figure 1. Substantive effects of financial crises on women's well-being with 95% confidence interval.

The upper-right panel of Figure 1 shows the magnitude of the impact of financial crises on women's participation in national legislatures. The predicted value of the outcome variable decreases from 15% to 13.8% in countries that experience any one of the five financial crises and from 15% to 9.1% when they face all five crises in the same year. Thus, a single financial crisis is associated with an 8% decrease in female legislators, whereas the presence of all crises is linked to an almost 40% decrease in female representatives. The lower-left panel of Figure 1 shows the model results for variable magnitude in female tertiary education. Here, the predicted value of the outcome variable declines from 51% to 50.6% when any of the five crises is present and from 51% to 48.7% when all five crises are present in a country in a given year. Substantively, this represents an approximately 1% decrease in female education for a single crisis and a nearly 5% decrease across the range of variation.

The lower-right panel of Figure 1 shows how the predicted value of the maternal mortality rate varies across the occurrence of financial crises. The prevalence of maternal mortality per 100,000 live births increases from 3.8 to 3.9 when a country faces any one of the crises and from 3.8 to 4.1 when all five crises affect the same country in a given year. The presence of a financial crisis is related to a 2.6% increase in maternal mortality, while the presence of all five crises is related to an approximately 8% increase in maternal mortality. Thus, our models show that financial crises have substantively significant negative effects on women's health with a discernable increase in maternal mortality rates in the crisis countries.

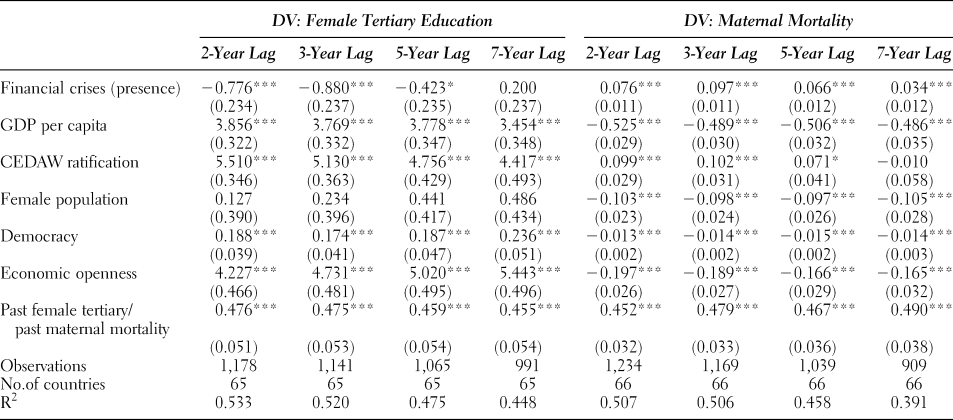

Tables 5 and 6 list the results of our tests for the possible lingering effects of financial crises. As discussed, there are substantive reasons to expect that crises may have lasting impact upon women's well-being. We assessed whether financial crises continue to have significant effects on women's well-being up to seven years after they end. The results of our models clearly show that women continue to experience difficulties in participating in the formal economy and national politics as well as declines in their education achievement and health even seven years after a crisis ends. Overall, our results are very consistent. Across the models in the tables, the adverse postcrisis effects for all five of our outcome variables are most apparent three years after a financial crisis; the coefficients across all models are the largest in the models with a three-year lag. These patterns indicate that a crisis may be a “formative moment” in a country that can have lasting impact upon its political and economic systems, to the detriment of female well-being.

Table 5. The lingering effects of financial crises on women's economic and political status

Notes: Standard errors appear in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. All time-variant control variables are lagged at t − 1.

Table 6. The lingering effects of financial crises on female education and maternal mortality

Notes: Standard errors appear in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. All time-variant control variables are lagged at t − 1.

Our findings regarding the control variables are largely consistent with our theoretical expectations. Economic development, as measured by GDP per capita, is positively associated with women's well-being. Similarly, women in countries that ratified the CEDAW are more likely to participate in the formal economy and politics and to enjoy better educational and health conditions. The number of females as a proportion of the total population also appears to have a positive influence on women. The economic openness variable is significant, too, which suggests that economic integration into the global economy positively affects women's well-being. The results for the democracy variable denote that there is no statistically significant difference between democratic and nondemocratic polities in women's involvement in the economy. Rather, democracy appears to matter most in predicting women's access to education, health outcomes, and participation in national politics.

CONCLUSIONS

We analyzed the impact of financial crises on women's well-being, specifically the degree to which crises affect women's participation in the formal workforce, their presence in politics, their educational attainment, and their health outcomes. Results from the cross-national data analysis lend robust support for the hypotheses that financial crises are likely to undermine women's status during the crisis years as well as several years following the end of crises. Our findings suggest that financial crises inflict both immediate and long-term costs on the well-being of women.

Most directly, our study speaks to the body of scholarship on the consequences of financial crises; we offer comprehensive and systematic evidence of the gendered impact of financial crises across both developed and developing countries. Economically, we offer corroboration that women bear the economic brunt of financial crises, and that the role of women as the de facto “social safety net” (Aslanbeigui and Summerfield Reference Aslanbeigui and Summerfield2001, 14) within their households comes at the price of their participation in the formal workforce (e.g., Antonopoulos Reference Antonopoulos2009; Singh and Zammit Reference Singh and Zammit2000).

We have also provided insight into the gendered impact of financial crises on female health and education, finding that crises have significant and lasting consequences upon societies that go beyond immediate ramifications for the workforce. In addition to the short-term damage wrought by financial crises, our findings suggest that policy responses to these crises, particularly austerity-driven cuts in social spending, may serve only to deepen and prolong the damage financial crises impose upon societies. Along those lines, our findings further demonstrate the shortcomings of neoliberal responses to financial downturns (e.g., Blanton et al. Reference Blanton, Blanton and Peksen2015b; Detraz and Peksen Reference Detraz and Peksen2016; see also Blyth Reference Blyth2013) since draconian responses to short-term capital downturns undercut a country's long-term need to develop its human capital through improved health and education outcomes.

Although much has been written about the substantial political impact of financial crises (e.g., Engelen Reference Engelen2011; Haggard Reference Haggard2000), our analysis is the first study to provide a comprehensive assessment of the gendered dimension of such political impact. Not only do financial crises result in lower levels of female representation in elected office, the damage to the “pipeline” of female candidates also persists for years after the crisis. At the least, our findings indicate that declarations of the “death of macho” (Salam Reference Salam2009) may be premature; on the contrary, crises may be “bringing macho back” into political office.

Our study also has implications for the broader body of literature on women and gender equality. We have demonstrated that economic difficulties and other adverse conditions instigated by crises are likely to impede female empowerment because of discernable reductions in women's involvement in the formal labor force, national politics, and higher education. The decline in women's access to education, economic resources, and voice over key political decision-making mechanisms during crises might further the persistence of hierarchical social structures, worsen gender relations at the societal and household levels, and enhance the existing socio-economic and political discrimination and inequality women face (Connell Reference Connell2003; Inglehart, Norris, and Welsel at al. Reference Inglehart, Norris and Welzel2002; Kenworthy and Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999).

As for policy implications, our findings indicate that governments should more intentionally focus attention and resources to mitigate the effects of crises on women's well-being. Greater investment in education, health, and poverty reduction programs might help reduce gender imbalances in access to education, the formal economy, and politics, which would in turn help women better cope with negative consequences of financial crises. Because gendered discrimination becomes more prevalent in the economy and politics during economically challenging times, it is also imperative for governments to strictly enforce existing women's rights laws and to actively seek ways to prevent gendered discrimination in the workplace and politics. Given the widely noted economic and political benefits of female empowerment (Coleman Reference Coleman2010; Elborgh-Woytek et al. Reference Elborgh-Woytek, Newiak, Kochhar, Fabrizio, Kpodar, Wingender, Clements and Schwartz2013; Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Ballif-Spanvill, Caprioli and Emmett2012; Klasen and Lamanna Reference Klasen and Lamanna2009), a focus on female empowerment and well-being can only serve to enhance postcrisis recovery. In the aftermath of crises, states cannot afford to ignore the specific plights and needs of half of their populations.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X18000545