Introduction

The period of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia between 1948 and 1989 created peculiar conditions for the operation of churches. Not only was the dominant ideology materialist and atheist, churches that were independent of the state and the ruling party represented a challenge to its totalitarian claims. For those reasons, the Communists introduced a wide array of anti-religious and anti-church measures. As one of the first measures, the Communist government in Czechoslovakia instituted state-paid salaries to the clergy, which should have deprived the clergy of their independence.

State-paid salaries to the clergy were introduced as a part of the anti-church campaign immediately following the Communist takeover in February 1948. In that campaign, church property was expropriated, bishops were put under surveillance, and many members of the clergy were arrested or intimidated. Churches were deprived of their outlets, schools, and social care institutions. In order to divide the clergy, the Communists established collaborative “patriotic” movements which defied the established hierarchies.

The collapse of the communist regimes of Central and Eastern Europe in 1989 brought about many changes, including those in church-state relations. Freedom of religion was restored early in the transition, state control of churches was removed, and some of the property taken by the communists was returned to the churches. Yet to restore the standard religious life of post-communist nations, it was not enough to repeal the regulations imposed by the communists; rather, new settlements between churches and states had to be negotiated redressing past injustices as well as setting new rules for the future. The duration and the results of the negotiations varied across the countries, and the Czech Republic is distinctive in both aspects (Minarik Reference Minarik2020).

The Czech Republic was the last among the Central European nations to settle with churches and the only country in the region that established complete financial separation between churches and the state. The settlement included partial in-kind restitution of church property taken by the Communists and financial compensation for the property that could not be returned to the churches. Also, the new arrangement ended the salaries introduced in 1949 which the state paid to the clergy (Minarik Reference Minarik2017).

The Czech Republic is well-known for its peculiar religious situation. Czechs are often cited for a high level of atheism (see, e.g., Greeley Reference Greeley2003; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2004) although the local sociologists of religion refer to the specific nature of Czech religiosity (e.g., Lužný and Navrátilová Reference Lužný and Navrátilová2001; Hamplová Reference Hamplová2008; Hamplová and Nešpor Reference Hamplová and Nešpor2009; Nešporová and Nešpor Reference Nešporová and Nešpor2009; Nešpor 2010). What is significant in Czech church-state relations is that the major churches are losing adherents in Czechia, and the number of people without religious affiliation is increasing. Czechs may not be atheists, but they certainly avoid organized religion.

Regarding the established typologies in church-state relations, the present-day Czech Republic is a clear case of friendly separation. On the other hand, Communist Czechoslovakia is quite peculiar; it was a state hostile to religion that refused church-state separation to maintain control over the churches. As a result, the secularized post-communist society, ripe for a church-state separation, inherited institutions that were quite an obstacle in that process.

In Alfred Stepan's (2000) typology, present-day Czechia represents a spontaneously secularized country with a friendly church-state separation; churches are free to participate in civil society, but the public role of religion is negligible. Yet, the path to separation was not straightforward due to the heritage of Communist institutions. The clergy's state-paid salaries were among the obsolete institutions; they would have been fit for a regime with an established church but not for the secularized society of the Czech Republic.

In Ahmet Kuru's (2007) typology, the transition from the Communist to the post-Communist church-state relations represents a shift between assertive and passive secularism. The Communists intentionally worked to eliminate religion from the public sphere during their rule while the present-day separation allows for public visibility of religion. The establishment of the state-paid salaries to the clergy could be viewed as a peculiar tool of assertive secularism. As passive secularism gained the upper hand in church-state relations, they must have been removed. The development between the collapse of Communist rule and the final church-state settlement represents the struggle between the two kinds of secularism.

Examination of state-paid salaries to the clergy seems worthwhile from several perspectives. As a tool introduced by the Communists, it is interesting to examine how this tool was used in the evolving anti-religious policies of the Communist regime. It is also interesting to compare the approach of the Communists to the democratically elected governments that came after 1989; such a comparison is telling of the differences and similarities in their attitudes toward religion. The observed development of the salaries paid to the clergy suggests that the clergy was disregarded by Czech governments, both Communist and post-Communist, with the exception of a short and extraordinary period early in the post-Communist transition.

The Legal Basis for the State-Paid Salaries of the Clergy

The Communist Party came to rule Czechoslovakia after the coup d’état of February 1948. The oppression of opposition and independent organizations including churches followed soon afterwards. The Communists used a wide array of measures aimed at both clergy and laity as well as church property. Especially in the earlier period, the use of violence was widespread, including show trials, imprisonment in labor camps, and torture. Simultaneously, the Communists attempted to seize control of the churches, particularly the Catholic Church, by taking its property and outlets, such as schools, hospitals, charities, and press (see, e.g., Minarik Reference Minarik2019).

In October 1949, the Communist government introduced new laws governing the relations between the state and churches. One of those new laws, the act “on Providing the Economic Security of Churches and Religious Societies by the State” (Act no. 218/1949 Coll.), set up the rules for financial relations between the state and the churches. With that law, the state assumed control over church property, patronage rights, and obligations, and the state committed itself to providing for the personal and material expenses of the churches.

The state-paid salaries came with a condition; the law introduced a “state approval” as a necessary condition for clergymen to minister and to receive salary. Providing religious services without state approval constituted a crime (“obstruction of state oversight of churches”). Also, the clergymen had to take an oath of allegiance to the state before assuming office. The Communist church laws followed a “carrot and stick” strategy, where the salaries represented the “carrot,” and the criminal code represented the “stick.”

The cabinet adopted several decrees establishing detailed rules for the different churches; however, they were rather similar, and there is no indication that the Communists intended to favor any of the religious groups. There were separate decrees for the Roman Catholic Church, the Czechoslovak Church (now Czechoslovak Hussite Church), protestant churches, the Orthodox Church, and other churches and religious societies.Footnote 1 Even though there might have been some plans in the initial period to use the Czechoslovak Church in the struggle against the dominant Catholic Church, such plans never materialized. Non-Catholic churches faced similar measures as the Catholic Church, although on a lesser scale.

The subsidies to the clergy were not invented by the Communists in Czechoslovakia. They followed earlier tradition established under the Austrian Empire, the “congrua laws” of 1885 and 1898, and upheld by Czechoslovakia in a 1926 law; in those laws, the state guaranteed a minimum income for the clergy (i.e., the “congrua”) and supplemented the income from other sources when it was insufficient. Earlier Austrian laws (of 1874 and 1890) also required state approval of clerical ministry; however, they were never abused by the state authorities (Kříž and Valeš Reference Kříž and Valeš2013). Unlike the Austrian emperors, the Czechoslovak Republic established after the First World War did not seek to actively promote religion, yet the government recognized the role of religion in society and continued to subsidize the income of Catholic priests as well as Protestant ministers. Although the Communist were significantly represented in the inter-war Czechoslovak parliament, they never were a part of the government, and their influence on the church-state relations was marginal.

To fully comprehend the gravity of the economic situation that the clergy faced, it is necessary to note that churches, particularly the Catholic Church, had been deprived of their property. Most of the landed property was taken in a land reform introduced after the First World War. The Church also suffered during the Second World War. German occupiers forcibly transferred property from Czech church organizations to Germans or for the use of Waffen SS. German authorities disbanded certain Catholic orders, evacuated several monasteries, and took their property (Kříž and Valeš Reference Kříž and Valeš2013). Thus, the German persecution of the Church foreshadowed the Communist persecution that was to come.

The Communists had already begun to move against the Church before the coup d’état of February 1948. In 1947, the Communist Party pushed through the act “on Revision of the First Land Reform” (Act no. 142/1947 Coll.) that enabled further seizures of church property. Finally, in March 1948, less than a month after the coup d’état, the parliament adopted the act “on the New Land Reform” (Act no. 46/1948 Coll.) that enabled the confiscation of all church land. Contrary to the legal provisions, compensation was rarely paid to the churches. The Communists also employed frauds and forced sales and gifts to transfer ownership titles, and some confiscations were unlawful even under the existing legal system (Kříž and Valeš Reference Kříž and Valeš2013).

The clergymen could hardly refuse the salaries. Catholic bishops instructed the priests to take the oath and accept the salary. The bishops themselves initially rejected both. Only 32 out of 5,028 Catholic priests that were invited to take the oath refused to take it; although, some priests were not even invited (Vaško Reference Vaško2004).Footnote 2 Bishops were not invited either, and most of them were interned. Eventually, the bishops also took the oath and received the salaries; however, the first generation of bishops consecrated before the Communist coup never collaborated with the Communists (Balík and Hanuš Reference Balík and Hanuš2013).

To increase the division among clergy, the Communists established “patriotic” organizations for those willing to collaborate with the Communist authorities. The first of them, The Peace Movement of the Catholic Clergy, was created in the early 1950s and lasted until 1968. Upon its failure, another organization was established in 1971 named The Association of Catholic Clergy Pacem in Terris. Both organizations attracted several hundred Catholic priests. Membership was often encouraged with bonuses added to the state-paid salaries but also through blackmail or intimidation.

During the Communist era, there were several minor amendments and one significant change regarding the salaries. Salaries were adjusted slightly in 1953 following a monetary reform of that year. A major increase in the salaries was contemplated in 1968, but it was never enacted due to the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia. The debate was revived in 1978 with a draft of two alternative proposals for an increase in salaries. The increase was finally enacted in 1981; although significant, it did not make up for the wage inflation between 1949 and 1981.

The collapse of the Communist regime in November 1989 created an opportunity to change the laws. As soon as January 1990, the parliament cancelled the requirement of “state approval,” and the churches could choose their ministers freely. In December 1990, the cabinet adopted a decree that significantly increased the salaries of the clergy. Furthermore, the parliament adopted an act that returned some of the property to the Catholic Church; particularly, it returned monasteries to religious orders and congregations.

In the post-Communist period, the salaries of the clergy were increased several times, and the restitution of property was discussed at length. Generally, the Czechs were reluctant to return the church property taken by the Communists while they were also dissatisfied with the system of financing established under Communist rule (Minarik Reference Minarik2017). The salaries of the clergy were increased on average every other year.Footnote 3 With the liberty of churches to select their own ministers, the number of state-paid clergy doubled between 1990 and 2010. The costs to the state increased about 10-fold in the same period; however, since prices increased about fivefold, the real costs only increased about twofold (which also means that the real per capita costs remained about the same).

The end of the state-paid salaries came in 2012 with a comprehensive settlement between the state and the churches. Embodied in the statute “on Property Settlement with Churches and Religious Societies” (Act no. 428/2012 Coll.), the settlement consisted of the restitution of church property, financial compensation for past injustices and a transitional financial scheme (Minarik Reference Minarik2017). The new arrangement made the churches completely financially independent of the state, thus after more than seven decades ending the system put in place by the Communists to control the clergy.Footnote 4

State-Paid Salaries of the Clergy Between 1949 and 2012

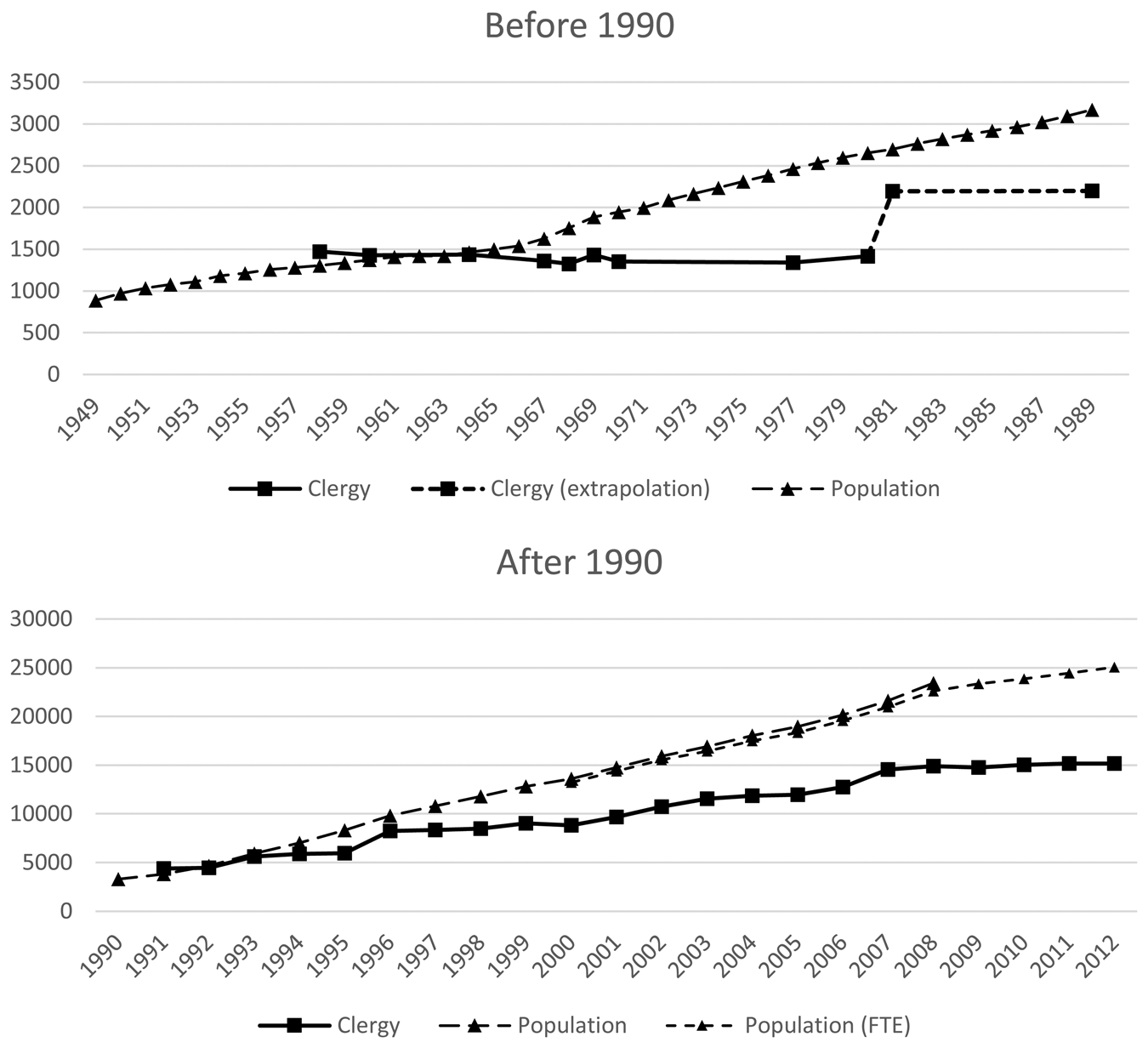

The data needed to evaluate the remuneration of Czech clergy are not easily available. For the post-1993 period, the data are well accessible from the Czech Ministry of Culture, the department of government responsible for church-state relations. When it comes to the earlier periods, data are scattered in various documents stored in archives, if available at all. Thus, the analysis of the pre-1990 period presented here builds only on a handful of data points.Footnote 5 More data could be retrieved from archives in future, yet there is no reason to expect a different picture of the historical reality. The general development of salaries is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mean salaries of clergy and mean monthly wages of Czech employees.

Notes: All values are in the local currency (Czechoslovak koruna before 1993, Czech koruna afterwards), unadjusted for inflation, before taxes. The presented average salaries of the clergy before 1989 combine archival data for Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic and those for all churches and the Catholic Church only, as available. Extrapolation between 1981 and 1989 is based on archival data from 1980 combined with legislation adopted in 1981. The time series of population mean wages is extended beyond 2008 with a series using different methodology (full-time equivalents instead of headcount).

Remuneration of the clergy was comprised of three elements. The basic salary was dependent on the length of service, increasing every 3 years. This was supplemented with an amount reflecting responsibilities; most priests receive a salary supplement for parish administration, and higher salary supplements were intended for professors of theology, vicars, and bishops. The third element of remuneration was a bonus for extraordinary performance that could be awarded by the government officials at their discretion. Extraordinary performance was typically interpreted as collaboration with the Communist officials, particularly through the “patriotic” organizations of the clergy. Government decrees specified the basic salary, the salary supplements, and the maximum amount of the bonus.

In the initial period, there are no aggregate data available, and only the statutory salaries can be evaluated. The monthly salary of a priest would have been between 600 and 1,320 Czechoslovak korunas, depending on his number of years in clerical service. Most priests also received a supplement of 200 korunas for the administration of a parish. The mean monthly wage in 1949 was 888 korunas, increasing to 1,111 korunas by 1953.Footnote 6 After an adjustment due to monetary reform in 1953, a priest could earn between 669 and 1,332 korunas plus 200 korunas for parish administration. By 1966, the mean monthly wage of Czech workers was higher than the maximum salary of a parish priest. Those numbers do not include possible bonuses for extraordinary performance, that is, for collaboration with the Communists. However, the bonuses were rather low.Footnote 7

The salaries of the clergy can be compared to those of teachers, which were decreed in April 1950, about half a year after the salaries of clergy were decreed. Depending on the number of years spent in the profession, a kindergarten teacher received 700–1,050 korunas, an elementary school teacher received 800–1,200 korunas, and a high school teacher 900–1,350 korunas, all of whom could receive further supplements and bonuses. Thus, the salaries of the clergy roughly corresponded to those of elementary school teachers. However, the remuneration of teachers was revised in 1956 with significant increases in the following years, while there was no such change regarding the salaries of the clergy.

Some data about the actual amount of money paid to the clergy are available for the late 1950s. In 1956, competencies over the church policy were transferred from the State Office for Church Affairs to a newly established Ministry of Education and Culture and its Secretariat for Church Affairs; however, the competencies regarding the salaries remained with regional authorities. Starting in 1958, the government began to significantly cut public expenditures on churches. In the first year, the cut was by 30%, and it continued to be reduced by about one-half in subsequent years. Only in the late 1960s, the period of Prague Spring, did the government become more generous toward churches. The proportion of personal expenditures to the total expenditures was raised from about two-thirds to 80%.

In the late 1950s, the personal expenditures became the most significant part of the churches' total expenditures that the Communists sought to decrease. Two strategies were adopted to achieve that end. First, the Communists tried hard to decrease the number of clergymen, which was quite successful (see Figure 2). Second, the Secretariat for Church affairs pushed to decrease the amount paid in bonuses (Chadimová Reference Chadimová2019). The “carrots” should have been reduced in favor of the “stick.” Obviously, the local authorities had been quite generous in the earlier period; thus, we may expect that the average salaries were slightly higher in the early 1950s.

Figure 2. Number of clergymen in the Czech Republic before 1990.

Note: The numbers are based on Babička (Reference Babička2005), Chadimová (Reference Chadimová2019), and Pešek and Barnovský (Reference Pešek and Barnovský1999; Reference Pešek and Barnovský2004).

From the 1960s on, the salaries paid to the clergy generally stagnated. There was a slight and short-lived increase at the end of the 1960s, and a substantial revision of clergy remuneration was considered at the time of Prague Spring. However, the restoration of conservative Communist leaders after the Soviet invasion of 1968, known as “normalization,” reversed most of the reformist policies of Prague Spring.

In the subsequent period, the only source of increase was the increasing age of the clergy. Between 1968 and 1980, the average duration of service among clergy increased by about 3 years. The number of priests serving more than 36 years, which roughly corresponds to reaching retirement age, increased from 12 to 39%. The salaries were increased with age by a fixed increment for every 3 years of service; however, when a priest reached retirement age, he received a lower salary along with a pension.

The only major revision in remuneration policy under Communist rule came in 1981. The revision increased the basic salaries (to 1,000–1,620 korunas), the supplements (to 700 korunas for a parish administrator), and the maximum amount of the bonuses for extraordinary performance. On average, the clergy's salaries increased by 55%. Such an increase could not reduce the income gap between the clergy and the rest of the population. According to the data from the Federal Statistical Office (1985, 349), real wages more than doubled, and real income more than quadrupled between 1953 and 1981. The living standards of priests were kept at the 1950s level, while for the general population they increased rapidly during that period.Footnote 8

Unfortunately, there are no data on how the Communist policies were perceived by the clergy and the population. In the late 1960s, Erika Kadlecova, a pioneer of the sociology of religion in Czechoslovakia, prepared a nationwide research project on the attitudes of clergy, the role of religion, the role of churches, and religiosity. That research was never conducted due to political changes after the Soviet invasion; Kadlecova was expelled from the Communist party, and the department of theory and sociology of religion at the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences was dissolved (Reference Nešpor and NešporNešpor n.d.).

Following the 1989 collapse of the Communist regime, the salaries of the clergy were increased several times. The initial change in 1991 raised them above the average wages of Czech workers. However, they remained close to the average for only 3 years. In the following years, the government increased the salaries paid to the clergy roughly to meet inflation. For the general population, wages grew more rapidly as the economic reforms transformed the Czech Republic from a centrally planned economy to a market economy. In the first decade of post-Communist transition, the mean nominal wage more than quadrupled, while the average salary of a priest only doubled. Between 1991 and 2012, the increase in the mean wage was almost sevenfold, while priests' salaries increased 3.5 times.

The development in the Communist and post-Communist period can be best compared in relative terms. In both periods, the remuneration of priests started at an above-average level and decreased over time. In the 1960s, the clergy's average salary fell below the mean wage; by the end of the 1970s, it dropped to about one-half of the mean wage. The reform of 1981 increased the salaries to about 80% of the mean wage; however, with the increase in the mean wage, the average salary of a priest should have fallen to about 70% by 1989.

In the post-Communist period, the relative decrease was more rapid. By 2000, the average salary of the clergy fell to two-thirds of the mean wage in the Czech economy. In subsequent years, it was maintained at a level between 60 and 70%. That is, even though the salaries never got as low as they were under Communist rule relative to the mean wage, they ended up at a roughly similar level. Considering the living costs, both the Communist and the post-Communist governments roughly maintained the living standards of priests at the same level as they had in the initial years of their rule, while the living standards of the Czech population were increasing.Footnote 9

Side-by-side comparison of different statistics clearly reveals the common trends in both periods (see Table 1). Average clerical salaries in the pre-1989 period were in the same proportion to mean monthly wages as in the post-1989 period. However, these statistics conceal the uneven increases in the clerical salaries which often put the clergy in a very unfavorable position. Unfortunately, the nature of the data does not allow for a more sophisticated statistical analysis.

Table 1. Change in mean salaries of clergy and mean monthly wages of Czech employees

Note: The pre-1989 period denotes 1958–1989, the post-1989 period denotes 1991–2012, due to data availability. Average remuneration in Czechoslovak or Czech koruna.

Discussion

Certain methodological issues arise in the comparison presented above. When using the mean wage over such a long period of time, one must bear in mind that the increase in the mean wages also reflects changes in the economic structure of society as well as increasing productivity. With time, the education of the Czech population increased, and the share of unskilled labor decreased. The mean wage of 1948 was driven by the wages of unskilled workers much more than in 1989 or 2012. Also, clergymen are typically highly educated; in the Catholic Church, dominant in the Czech Republic, all priests have a college education.

It would be best to compare priestly salaries with the mean earnings of workers with equivalent education. However, such data are not available. Moreover, in a centrally planned economy under communist rule, wages do not necessarily reflect education, skills, or productivity; they often follow political criteria favoring selected groups of workers and the apparatus necessary to maintain power. Also, the differences in wages were relatively low in communist economies. If we were to take the sector of education for comparison, the results would be very similar to those presented above.Footnote 10

Before making a hasty conclusion about the Czechs, it is worth considering the situation in Slovakia. The two successor states of Czechoslovakia not only share a history under Communist rule, both countries also maintained the original law governing financial provisions to the churches well into the post-Communist era. Actually, Slovakia continued to pay the salaries of the clergy until 2019. Starting in 2020, the state pays a lump sum subsidy per year to every church, and the churches can decide how they spend the money; that is, the churches can set their own rules for the remuneration of the clergy.

The difference in religiosity between the Czech Republic and Slovakia is stark. While the first is often cited as one of the most atheist countries in Europe, Slovakia is one of the most religious. Although secularizing, Slovakia is still closer to the Polish model than to any of the Western nations. Froese (Reference Froese2005) gives some explanation to the differences between Czechs and Slovaks, mostly pointing to the various historical differences in the relationship between religion and nationalism.

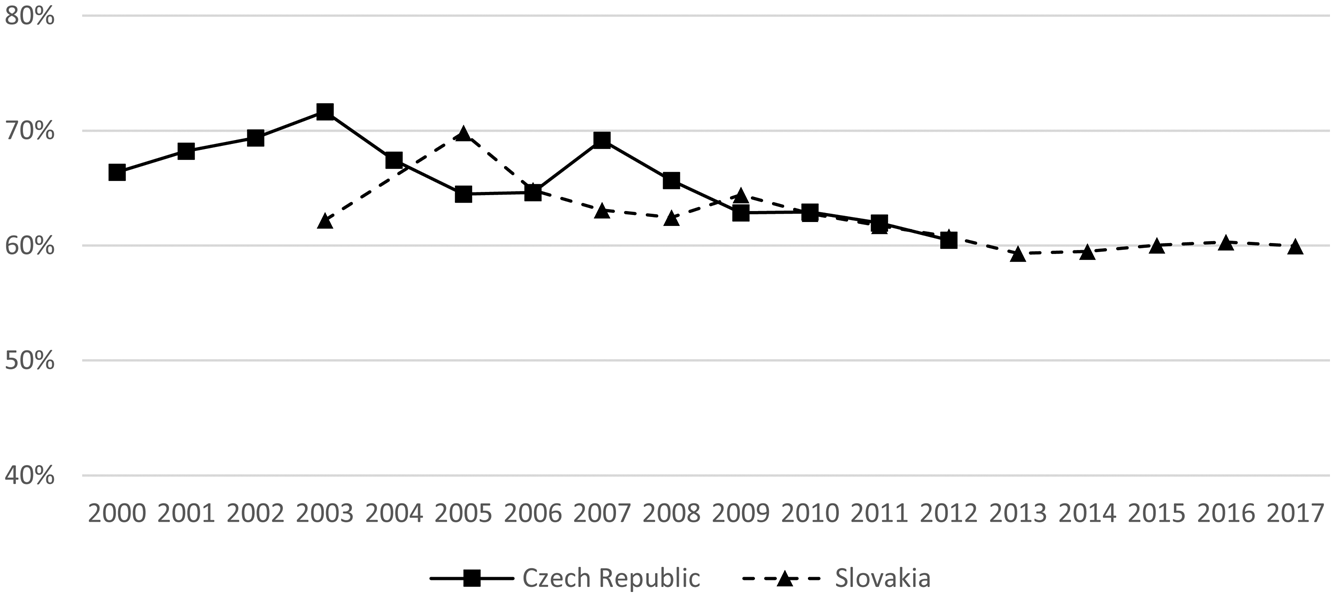

Interestingly, when we compare the salaries of the clergy in the Czech Republic and Slovakia in the beginning of the millennium, there is no difference between the two countries. Figure 3 depicts the ratio of the mean salaries of the clergy to the mean wages of workers in both countries; despite occasional hikes, the salaries of the clergy are falling towards 60% of the mean wage. Even in Slovakia, the salaries of the clergy were obviously not an issue attracting any attention from either politicians or the masses.

Figure 3. Ratio of mean salaries of the clergy to mean wages in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Note: The ratio is calculated from data provided by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Republic, the Czech Statistical Office, and the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic.

However, one should not conclude that Czechs and Slovaks are the same when it comes to church-state relations. Unlike in the Czech Republic, Slovak churches received back most of their property in the 1990s. Thus, continuing the payment of salaries to the clergy should be interpreted in part as compensation for the property not restituted and in part as an outright subsidy to the churches. In the Czech Republic, little property was restituted before 2012 (Minarik Reference Minarik2017; Reference Minarik2020). Thus, the state acted as if it were still accepting the patronage duties assumed by the Communists in 1949.

The system of church financing introduced by the Communists has also had a detrimental effect on the willingness of the adherents to support their churches. Donations and tithing were perceived as unnecessary where the state was paying the church. This is not specific to the Czech case; the willingness to contribute to churches is generally low in post-communist countries, and it appears to depend on the system of state support (Zrinščak Reference Zrinšcak, Barbalet, Possamai and Turner2011). Czech churches expressed their worries that their members might be even less willing to contribute after the property settlement as the people would misjudge the ability of the churches to support themselves out of the restituted property. The period of economic dependence on the state, both under Communist rule and after its collapse, clearly altered the attitudes of churchgoers, and it will take time for the churches to adapt to the separation model.

Considering the differences between Czechia and Slovakia described above, it seems that the reluctance of the Czech government to restitute church property is more telling of the attitude of the Czechs toward organized religion and the Catholic Church in particular. While the decrease in remuneration of the clergy could be attributed to disregard for the churches, intentional under Communist rule and perhaps unintentional afterwards, the failure to restitute the church property cannot be attributed to negligence. Unlike the salaries, the restitution of property was debated publicly for a considerable period of time. Ultimately, although the Czech government in the post-Communist period did not endorse an anti-religious doctrine, practical economic policy toward churches was not too different from that of the Communists.

The development of the Czech church-state relations can perhaps best be framed in Ahmet Kuru's (2007) typology of assertive and passive secularism. First, there is the presence of the ancient regime in the first half of the 20th century, the Austrian Empire backing the Catholic Church, creating a condition favoring assertive secularism. The idea of an ancient regime is almost absent in the post-Communist society; thus, there is a shift toward passive secularism.

Further, there is the position of secular groups toward religion's public role. Since religion had lost much of its prominence during the 20th century, the public presence of religion no longer mobilizes against it. Again, those are conditions favoring a shift from assertive to passive secularism. Additionally, religious groups were open to separation in the post-Communist times, while the Catholic Church might have sought to maintain some kind of establishment in the earlier periods.

Finally, perhaps the most important condition in the Czech case is the consensus versus conflict between secular and religious groups. There was certainly some tension between churches and many political and social groups in interwar Czechoslovakia. After the Communist coup, the relation between the secular groups controlled by the Communists and churches may only be called an open conflict. Those conditions clearly favored assertive secularism. In the post-Communist period, the relationship may be characterized as quite consensual, especially in the early period after the collapse of the Communist regime when the new representatives of civil society and the churches shared the victory over a common enemy. This has certainly not concerned the whole of Czech society, but again, it was another condition shifting Czechia toward passive secularism.

Conclusion

The history of the state-paid salaries of the Czech clergy well represents the development of church-state relations and general attitudes toward organized religion in Czechia. Following the collapse of the Austrian Empire and the establishment of Czechoslovakia, secularization accelerated in Czechia; that development was also reflected in the church-state relations which were generally friendly, yet tense at some moments.

The Communist takeover after the Second World War began a period of militant struggle against religion. The struggle required control over churches, especially over the dominant Catholic Church. The Communists not only established an institutional structure suitable for that purpose, including the state-paid salaries, but through education and propaganda also strived to alter the attitudes of the Czech population against churches and religion as such.

The collapse of Communist rule in 1989 ended the period of religious repression; however, the transformation of the institutional framework took another two decades. During that period, a struggle between the assertive secularism typical for the former regime and the passive secularism typical for a significant portion of Czech society hindered the final settlement. Only in 2012 did the passive secularism gain an upper hand in a rather friendly church-state separation.

From the perspective of the clergy, the immediate outcome of both the Communist and the post-Communist period was similar. In both periods, their living standards were deteriorating, and the issue was neglected by both the politicians and the general public. Perhaps the chief difference comes from the different goals of the political representatives; in the latter period, it was not the destruction of religion as such. Thus, the churches were ultimately separated from the state and left to take care of themselves, for better or worse.

Funding

This research was supported by the Czech Science Foundation under grant no. 19-07748S.

Pavol Minarik is an assistant professor of economics at the J. E. Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic. His research focuses on the economics of religion in communist and post-communist Central and Eastern Europe.