Introduction

Driven by global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy theories are currently at the center of political and public debates. Conspiracy theories attribute major political or societal events to an elaborate plan, carried out by a secret coalition of individuals who pursue malicious goals (van Prooijen, Reference van Prooijen2018; Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Uscinski, Sutton, Cichocka, Nefes, Ang and Deravi2019). Belief in conspiracy theories has potentially harmful effects on many aspects of political behavior, such as political engagement, intergroup attitude, and vote choice (Jolley and Douglas, Reference Jolley and Douglas2014; Jolley et al., Reference Jolley, Meleady and Douglas2020; Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021). The literature on the causes of beliefs in conspiracy theories has identified numerous cognitive, social, and ideological determinants of conspiratorial thinking (Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Uscinski, Sutton, Cichocka, Nefes, Ang and Deravi2019). While scholars have long noted a link between conspiracism and believe in the paranormal (Adorno et al., Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950; Barkun, Reference Barkun2013), religious beliefs and spirituality have only recently become a focus in quantitative research (Ward and Voas, Reference Ward and Voas2011; Griera et al., Reference Griera, Morales I Gras, Clot-Garrell and Cazarín2022; Halafoff et al., Reference Halafoff, Weng, Roginski and Rocha2022).

Accordingly, the empirical evidence for the relationship between religiosity, spirituality, and belief in conspiratorial forces is far from conclusive. Although individual religiosity is often positively, albeit moderately, associated with specific conspiracy beliefs and a general conspiracy mentality (e.g., Jasinskaja-Lahti and Jetten, Reference Jasinskaja-Lahti and Jetten2019; Teličák and Halama, Reference Teličák and Halama2021; Yendell and Herbert, Reference Yendell and Herbert2022; Frenken et al., Reference Frenken, Bilewicz and Imhoff2023), some studies find no robust evidence for such an association (e.g., Čavojová et al., Reference Čavojová, Secară, Jurkovič and Šrol2019; Lobato and Zimmerman, Reference Lobato and Zimmerman2019; Farkhari et al., Reference Farkhari, Schlipphak and Back2022; Ladini, Reference Ladini2022).

We pursue two objectives in the present study. First, drawing on the typology of religious attitudes of Wulff (Reference Wulff1997), we want to shed light on the relationship among different dimensions of individual religiosity, spirituality, and beliefs in conspiracy theories. Specifically, we argue that a “literal understanding” (literal affirmation and literal disaffirmation) of religious content promotes belief in conspiracy narratives because they are linked to intuitive thinking. In contrast, symbolic interpretations of religious texts and teachings will reduce the probability of endorsing conspiracy narratives because this involves more analytic thinking. In addition, we suppose that holistic spirituality increases the endorsement of conspiracy theories because there is an “elective affinity” between spiritual and conspiratorial belief systems that results from their similarities in intuitive (versus analytic) reasoning. Second, based on dual-process models of reasoning (Stanovich, Reference Stanovich2010; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2012), we directly test whether the relationship between religiosity, spirituality, and conspiracy beliefs can be accounted for by individual differences in analytic cognitive style.

Religion, spirituality, and conspiracy beliefs

In recent years, many theoretical works have addressed the relationship of religiosity, spirituality, and belief in conspiratorial forces (Ward and Voas, Reference Ward and Voas2011; Asprem and Dyrendal, Reference Asprem, Dyrendal, Dyrendal, Robertson and Asprem2018; Robertson and Dyrendal, Reference Robertson, Dyrendal and Uscinski2018; Dyrendal, Reference Dyrendal, Butter and Knight2020). Scholars of conspiracy beliefs often differentiate between beliefs in specific conspiracy theories (e.g., the assassination of John F. Kennedy) and a general conspiracy mentality. Based on the observation that specific beliefs tend to form a coherent belief system (Goertzel, Reference Goertzel1994), conspiracy mentality referes to a general disposition to explain events as controlled by malicious forces acting in secret (Imhoff and Bruder, Reference Imhoff and Bruder2014).

In this context, scholars often emphasize the commonality of conspiracy beliefs and “holistic spirituality” (Heelas and Woodhead, Reference Heelas and Woodhead2005). Holistic spirituality is a term used to summarize beliefs and practices developed via New Age thought, Anthroposophy, Theosophy, esotericism, etc. (Hanegraaff, Reference Hanegraaff1996). These commonly assume the universal connectedness of all the elements in the universe and thus contest the duality between body and soul that characterizes Christian beliefs (Heelas and Woodhead, Reference Heelas and Woodhead2005). Holistic beliefs stress the importance of individual experiences with transcendental realities to guarantee the authenticity of beliefs and the truth of any claims related to these beliefs. Within the holistic milieu, beliefs and practices serve the self, and individuals within this milieu reject the traditional forms of ecclesiastical authority institutionalized in churches. Holistic spiritualities, therefore, developed in opposition to Christian churches, contest the monopoly the latter claim on religious truth (Siegers, Reference Siegers2012). Such contestation is not limited to the authority of churches but extended to domination and exploitation in political and economic terms, defending an ethic of equality and ultimate justice (Sointu and Woodhead, Reference Sointu and Woodhead2008).

Adherents to holistic spiritualities often assume that there is secret knowledge being suppressed by orthodoxy. Their combination of stigmatized knowledge and a mystical search for hidden truth creates a strong distrust of the political, scientific, and religious “establishment” (Barkun, Reference Barkun2013; Asprem and Dyrendal, Reference Asprem and Dyrendal2015). Thus, holistic spiritualities and conspiracy beliefs are both at odds with established “truth-making institutions” (Boyer, Reference Boyer2020, 87) and contest the domination of these institutions. Spiritual believers see themselves in opposition to the Christian mainline congregations that dominate the religious field, just as conspiracy believers see themselves in opposition to the mainstream worldviews with regard to their political attitudes, health beliefs, and behaviors (Lamberty and Imhoff, Reference Lamberty and Imhoff2018; Wood and Douglas, Reference Wood, Douglas, Dyrendal, Robertson and Asprem2018). Scholars of conspiracy beliefs argue that this similarity explains the higher disposition of spiritual believers toward conspiracy beliefs because of their deeply rooted conviction of having insights into the truth of hidden power structures (Robertson and Dyrendal, Reference Robertson, Dyrendal and Uscinski2018). Ward and Voas (Reference Ward and Voas2011) even argue that a “conspiritual” movement has emerged on the web with a significant overlap between holistic beliefs and conspiracy dispositions (Asprem and Dyrendal, Reference Asprem and Dyrendal2015). Empirical research, however, has shown that at the individual level spirituality is moderately correlated with conventional religiosity, especially with a socialization into Christian religiosity (Siegers, Reference Siegers2012; Tromp et al., Reference Tromp, Pless and Houtman2020). In reality, the two concepts are less distinct than the theoretical discussion suggests.

The rationale explaining the association of conventional religiosity with conspiracy beliefs is less convincing. The discussion thus far has suggested that this correlation might be driven by the content of religious beliefs or exposure to religious teachings of Christian churches or other religious communities (Robertson and Dyrendal, Reference Robertson, Dyrendal and Uscinski2018). Some scholars stress that both religions and conspiracy narratives refer to some form of salvation (Keeley, Reference Keeley, Dyrendal, Robertson and Asprem2018), assume the existence of invisible powers that operate beyond the realm of (direct) human experience (Ladini, Reference Ladini2022), tend to establish agency and intentionality in unrelated events (Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Sutton, Callan, Dawtry and Harvey2016; Galliford and Furnham, Reference Galliford and Furnham2017), or share the rejection of scientific research and evidence (Łowicki et al., Reference Łowicki, Marchlewska, Molenda, Karakula and Szczepańska2022). However, there are also differences between religious and conspiratorial belief systems. First, whereas transcendental power in conventional religion strives for the good, the hidden powers of conspiracy narratives inflict harm on the powerless (Keeley, Reference Keeley, Dyrendal, Robertson and Asprem2018). Second, churches are unlikely to support and disseminate conspiracy narratives because they mainly support the existing political order (Robertson and Dyrendal, Reference Robertson, Dyrendal and Uscinski2018). For instance in the German context of strong ties between the mainline Christian churches and the state, political and social statements of the churches are aligned to the constitutional order. Conspiracy beliefs mobilizing against minorities, political elites, or science will not be supported.

If the correlation between religiosity and conspiracy beliefs is not due to similar content, it is more likely due to cognitive and perceptual characteristics of individuals that predispose individuals to religious and conspiracy beliefs (Wood and Douglas, Reference Wood, Douglas, Dyrendal, Robertson and Asprem2018). Boyer (Reference Boyer1994) introduced the concept of “minimal counter-intuitiveness” to explain why religious information is easier to remember for human brains. The concept has also been used to explain belief in conspiracy theories, especially its counter-schematic nature, i.e., the opposition to mainstream worldviews (Wood and Douglas, Reference Wood, Douglas, Dyrendal, Robertson and Asprem2018). This means that the common denominator between religiosity and conspiracy may be the way in which individuals process certain forms of information.

In summary, the theoretical discussion oscillates between emphasizing similarities in content or underlying cognitive styles to explain associations between spirituality, religiousness, and conspiracy beliefs. This theoretical ambiguity is also reflected in the extant empirical evidence. Overall, the indicators of the strength of religious belief appear to be weakly to moderately positively related to a belief in conspiracy theories, although these results are inconsistent. One obvious reason for this is the low reliability and validity of the adopted measurement instruments. Most studies use single-item measures of self-reported religiosity (e.g., Galliford and Furnham, Reference Galliford and Furnham2017), of the importance of religion or God in one's life (e.g., Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017), or of the frequency of church attendance (e.g., Lobato and Zimmerman, Reference Lobato and Zimmerman2019). Studies using more extensive multiple-item measures of religiosity tend to report stronger associations (Jasinskaja-Lahti and Jetten, Reference Jasinskaja-Lahti and Jetten2019; Łowicki et al., Reference Łowicki, Marchlewska, Molenda, Karakula and Szczepańska2022; Yendell and Herbert, Reference Yendell and Herbert2022; Frenken et al., Reference Frenken, Bilewicz and Imhoff2023; Walker and Vegter, Reference Walker and Vegter2023). Only one study distinguishes different religious attitudes, finding positive effects of religious fundamentalism but not of centrality of religious beliefs on conspiracism (Łowicki et al., Reference Łowicki, Marchlewska, Molenda, Karakula and Szczepańska2022). Another reason could be that belief in conspiracy theories is captured both at the level of specific conspiracy narratives and at the level of general dispositions toward conspiracy thinking (Imhoff and Bruder, Reference Imhoff and Bruder2014).

In their meta-analysis, Frenken et al. (Reference Frenken, Bilewicz and Imhoff2023) find a mean weighted correlation of r = 0.25 between religiosity and belief in specific conspiracy theories and r = 0.10 with indicators of a generalized conspiracy mentality. However, they include only nine studies in their meta-analysis. A more extensive meta-analysis by Stasielowicz (Reference Stasielowicz2022) reports a mean correlation of r = 0.14 based on 51 studies, but these correlations are highly scattered. He thus observes no differences between general or specific conspiracy beliefs. However, there is a difference regarding the number of items measuring religiosity. Studies with multiple-item scales have yielded, on average, higher correlations (r = 0.22) than studies with single-item measures (r = 0.10). Unfortunately, Stasielowicz (Reference Stasielowicz2022) does not separate religious beliefs from holistic spirituality in his meta-analysis.

The role of post-critical beliefs

We suggest including research on attitudes towards religious information into the study of the association between religiosity and conspiracy beliefs in terms of information processing. The psychology of religion has identified preferred ways of processing religious information resulting in different types of attitudes towards religious texts and teachings (Hutsebaut, Reference Hutsebaut1996; Wulff, Reference Wulff1997). Wulff (Reference Wulff1997) distinguishes two dimensions of the interpretation of religious information. The first is a literal versus symbolic interpretation of religious texts and teachings. The second is an inclusion versus exclusion of transcendence. Based on these two dimensions, he defines four ideal types of attitudes toward religion. First, orthodoxy is the literal affirmation of transcendental realities. Individuals hold literal beliefs in religious texts and believe in an immediate access to transcendental reality (e.g., the relationship to a personal god). An example of religious literalism in its purest form is religious fundamentalism. The second type is the literal disaffirmation of transcendental realities, also called external critique. This attitude interprets any kind of religious sources literally but rejects the possibility of any transcendental reality or the truth of any religion. External critique entails that religious teachings are irrational and, thus, erroneous. Any symbolic interpretation of religious information is excluded. Religious information is treated as it is formulated in the original scriptures or oral transmissions. Anti-religious attitudes and atheism are examples of literal disaffirmation. Orthodoxy and external critique both share the emphasis on literal interpretations of religious texts and teachings.

The third attitude combines a symbolic interpretation with an affirmation of transcendence. This results in an attitude toward religion that Hutsebaut (Reference Hutsebaut1996) has called a second naïveté (with orthodoxy being the first naïveté), referring to Paul Ricoeur's notion of post-critical thought. This attitude to religion stresses the symbolic meaning of religious texts or transmissions and the need to interpret historical religious thought, including critical questions concerning religions and their truth claims. This attitude tries to reconcile a rational approach to religion with an affirmation of a transcendental reality (e.g., it combines a religious belief with a symbolic representation of the world).

The last form is historical relativism, combining symbolic interpretation with the exclusion of transcendence. This stance toward religion denies the existence of any transcendental reality but acknowledges that religious teachings or transmissions contain information about a society's social and moral order. It conceives religion as a social construction by humans.

Analytic cognitive style and conspiracy beliefs

As discussed above, the empirical relationship between spirituality, religiousness, and believe in conspiracy theories is often explained with reference to similarities in terms of content or cognitive styles. Yet we contend that the substantive similarities between religious beliefs, spirituality, and support for conspiracy theories are negligible, making the argument unconvincing. By contrast, research in political psychology suggests that the observed correlations are explained by the fact that religious beliefs, conspiracy ideation, and other so-called epistemically unfounded beliefs (e.g., belief in the paranormal and pseudo-science) are rooted in individual differences in thinking styles especially with regard to information about potential transcendental realities (Baumard and Boyer, Reference Baumard and Boyer2013; Lobato et al., Reference Lobato, Mendoza, Sims and Chin2014; Ståhl and van Prooijen, Reference Ståhl and van Prooijen2018; Wood and Douglas, Reference Wood, Douglas, Dyrendal, Robertson and Asprem2018). Dual process theories of thinking distinguish between intuitive and holistic information processing styles (type 1) and more analytic and deliberative thinking (type 2) processes (Evans, Reference Evans2008; Stanovich, Reference Stanovich2010; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2012).Footnote 1 While type 1 reasoning is fast, heuristic, and based on autonomous reactions, the type of processing involved in type 2 reasoning is under volitional control, piecemeal, and in line with epistemic rationality. Intuitive responses are an evolutionary default option of the thinking system, but they can be interrupted and inhibited by deliberative processes if someone has a disposition to engage in critical thinking.

This view on human information processing implies that people adopt belief systems that are consistent with their preferred way of thinking. According to Ståhl and van Prooijen (Reference Ståhl and van Prooijen2018), type 1 reasoning compels individuals to epistemically unfounded beliefs because intuitive thinkers are less willing to scrutinize arguments and discern weak from strong evidence in favor of a claim. As a result, intuitive thinkers are more likely to exhibit reasoning bias such as illusory detection of patterns and agency which is typically for religious and conspiracist belief systems (Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Sutton, Callan, Dawtry and Harvey2016; van Elk et al., Reference van Elk, Rutjens, van der Pligt and van Harreveld2016). This argument is consistent with empirical studies that find robust negative associations between performance-based measures of analytic cognitive style with conspiracy thinking (Binnendyk and Pennycook, Reference Binnendyk and Pennycook2022; Yelbuz et al., Reference Yelbuz, Madan and Alper2022) and religious beliefs (Gervais and Norenzayan, Reference Gervais and Norenzayan2012; Pennycook et al., Reference Pennycook, Cheyne, Seli, Koehler and Fugelsang2012; Shenhav et al., Reference Shenhav, Rand and Greene2012).

Hypotheses

At a cognitive level, different attitudes toward religious information are tied to type 1 and type 2 reasoning. Conspiracy beliefs emerge when information is not validated through truth-making institutions with their—at least partly—emphasize on epistemic rationality but accepted “literally” as part of the more general frame of the “evil” elites and the “good” people. The literature has shown that the literal processing of religious content is associated with exclusionary attitudes (Duriez, Reference Duriez2004) and cognitive rigidity, entailing high needs for cognitive closure, dogmatism, and intolerance of ambiguity (Duriez, Reference Duriez2003; Freidin and Acera Martini, Reference Freidin and Acera Martini2022). Thus, we hypothesize that the attitudes toward religion that involve a “literal understanding” (literal affirmation and literal disaffirmation) of religious information are positively related to beliefs in conspiracy narratives because both religious attitudes are rooted in intuitive or type 1 reasoning. Put differently, we interpret the connections between Christian religiosity, holistic spirituality, and conspiracy beliefs as caused by shared covariance with lower levels of cognitive reflection (see also Frenken et al., Reference Frenken, Bilewicz and Imhoff2023). However, there is a lack of direct evidence for the hypothesis that both belief systems stem from similar forms of intuitive information processing. Thus, we formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Orthodoxy is positively related to conspiracy beliefs.

Hypothesis 2: External critique is positively related to conspiracy beliefs.

Our hypotheses also imply that anti-religious attitudes such as atheism are positively related to conspiracy beliefs, contradicting research that relates religious disbelief to openness and analytic thinking (see Uzarevic and Coleman, Reference Uzarevic and Coleman2021). However, the concept of literal disaffirmation is more akin to dogmatic atheism, which rejects religious meaning based on less analytic, closed-minded, and rigid reasoning (Kossowska et al., Reference Kossowska, Czernatowicz-Kukuczka and Sekerdej2017).

In contrast, we assume that symbolic interpretations of religious information require analytic thinking (type 2) because they involve a rationalization of religious ideas, for example, through historical contextualization. With symbolic interpretations, religious information is embedded into epistemic rationality. Therefore, religious attitudes based on symbolic interpretation are negatively related to conspiracy beliefs due to a greater tolerance of uncertainty and higher levels of analytic reasoning. Therefore, we formulated the two following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Second naivité is negatively related to conspiracy beliefs.

Hypothesis 4: Relativism is negatively related to conspiracy beliefs.

The underlying assumption of hypotheses 1–4 is that correlations between religious attitudes and conspiracy beliefs are due to a shared emphasis on type 2 reasoning. Thus, we further hypothesized that associations between religious attitudes and conspiracism disappears or diminishes after controlling for individual differences in analytic cognitive style, as indicated by the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT; Frederick, Reference Frederick2005), a performance-based measure of individual differences in thinking styles:

Hypothesis 5: Religious attitudes are unrelated to conspiracy beliefs when individual differences in analytic cognitive style are controlled for.

Finally, we argue that analytic cognitive style might also account for the relationship between holistic spirituality and conspiracy beliefs. Accordingly, if the relationship between holistic spirituality and conspiracy beliefs disappears when controlling for cognitive reflection, this would confirm the similarities of different styles of religiosity and spirituality in information processing. Therefore, our last hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 6: Holistic spirituality is unrelated to conspiracy beliefs when individual differences in analytic cognitive style are controlled for.

Method

Participants and design

A total of N = 1,114 adult German citizens completed a web survey about religious orientations, which contained measures of religious, spiritual, and conspiratorial beliefs as well as other measures for an unrelated study. Participants were recruited through mingle.respondi.com, a large commercial opt-in online panel in Germany. Participants were selected using a quota sampling method to match the sample to the German population regarding age, gender, education, and region of residence. The survey was fielded from June 4 to 10, 2021. After the listwise deletion of missing responses, the final sample included 831 participants (51.6% male) aged 18–81 years (M = 48.8, SD = 16.5). In the final sample, 34.5% of the respondents had a lower secondary education (9 years of schooling or no educational certificate), 30.3% had an intermediary secondary qualification (10 years of schooling), and 35.1% had a higher secondary qualification (12 or 13 years of schooling). A majority, 43.9%, identified themselves as nondenominational, 26.5% considered themselves Protestant, and 24.2% Roman Catholic. Other religious affiliations comprised only a small portion of the sample (5.4%). Compared to the representative German General Social Survey (GESIS, 2022), nondenominational persons were thus overrepresented in our sample, while Catholics were underrepresented. The proportions of Protestants and other religious denominations were roughly equal to the GGSS estimates (see online supplementary material).

Measures

Conspiracy beliefs

Endorsement of specific conspiracy theories was assessed with 13 items reflecting different conspiracy narratives in Germany (see Table 1). All items were rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely) and averaged to create a composite index of conspiracy beliefs. Raykov's rho for the index was ρ = 0.94. To measure the general tendency for conspiratorial thinking, we administered a brief version of the Conspiracy Mentality Scale (Imhoff and Bruder, Reference Imhoff and Bruder2014). Conspiracy mentality refers to the propensity to suspect clandestine and malicious groups are behind social and political phenomena (see Table 1). The scale consisted of five items scored on five-point scales (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that were averaged to indicate a higher conspiracy mentality (ρ = 0.81).

Table 1. Conspiracy belief items

Note: Endorsement rate refers to participants who scored above the midpoint (4) of the seven-point scale (specific conspiracy beliefs) or responded with “agree” or “completely agree” (conspiracy mentality). An asterisk denotes reversed items. In this case endorsement rate refers to disagreement with the item.

Religious attitudes

Participants completed the German short version of the Post-Critical Beliefs Scale (PCBS; Duriez et al., Reference Duriez, Appel and Hutsebaut2003, Reference Duriez, Soenens and Hutsebaut2005). This questionnaire consists of 18 items that cover the four types of religious attitude: orthodoxy, external critique, second naivité, and relativism. All items were scored on five-point scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This instrument was developed to be independent of any specific (Christian) denomination and has demonstrated high reliability and validity (Duriez et al., Reference Duriez, Fontaine and Hutsebaut2000; Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Duriez, Luyten and Hutsebaut2003). In the focal sample, the four scales exhibited very good to acceptable composite reliability (orthodoxy ρ = 0.83, external critique ρ = 0.84, second naivité ρ = 0.84, and relativism ρ = 0.72).

To capture the classical tripartite concept of religious belonging, belief, and behavior, we included questions on religious affiliation, degree of religiosity (1 = not at all religious, 7 = extremely religious), and frequency of church attendance (1 = daily, 2 = more often than once a week, 3 = once a week, 4 = at least once a month, 5 = only on special holidays, 6 = less often, 7 = never).

Holistic spirituality

Holistic spirituality was measured using a five-item scale that was developed for this study. Sample items included the following: “I have my own way of connecting with the divine, without churches or church services” and “For me, spirituality means recognizing how all things in the cosmos are interconnected.” Participants indicated their agreement on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale exhibited high reliability (ρ = 0.88). We also asked participants how spiritual they consider themselves (1 = not at all spiritual, 7 = extremely spiritual) and how often they take time for meditation, inner reflection, or something similar (1 = daily, 2 = more often than once a week, 3 = once a week, 4 = at least once a month, 5 = only on special holidays, 6 = less often, 7 = never).

Analytic cognitive style

Analytic cognitive style was assessed by the CRT (Frederick, Reference Frederick2005). The CRT is a three-item instrument, which measures the tendency to suppress intuitive answers to reasoning problems and engage in analytic thinking. Each open-ended question is formulated so that there is an intuitive, but incorrect answer and a logically correct answer, such as the bat and ball problem (“A bat and ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”). We scored each item as either correct (1) or incorrect (0). The answers were summed to create a composite score with higher values which indicate greater willingness to engage in analytic thinking (KR-20 = 0.71).

Covariates

We control for the sociodemographic covariates of age (in years), gender (1 = male, 0 = female), education (1 = low, 9 years of schooling or less, 2 = medium, 10 years of schooling, 3 = high, at least 11 years of schooling), monthly household income recoded to income quintiles (1 = less than 1.500 euro, 2 = 1,500–1,999 euro, 3 = 2,000–2,999 euro, 4 = 3,000–3,999 euro, 5 = 4,000 euro or more), and political orientation (1 = very left, 7 = very right).

Results

The descriptive statistics for the main variables and their correlations are presented in the online supplementary material. To test our hypotheses, we fitted ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models with robust standard errors that separately predicted specific conspiracy beliefs and conspiracy mentality. For both dependent variables, we first entered the measures for self-reported religiosity, religious practice, spirituality, sociodemographic characteristics, and political orientation. In a second step we included the post-critical belief scale. In a third step, we eventually entered analytic cognitive style to assess how the relationship between the religious and spiritual variables changes when analytic thinking is controlled for. All continuous variables were recoded to range from 0 to 1 to compare the magnitude of the effects of the predictors.

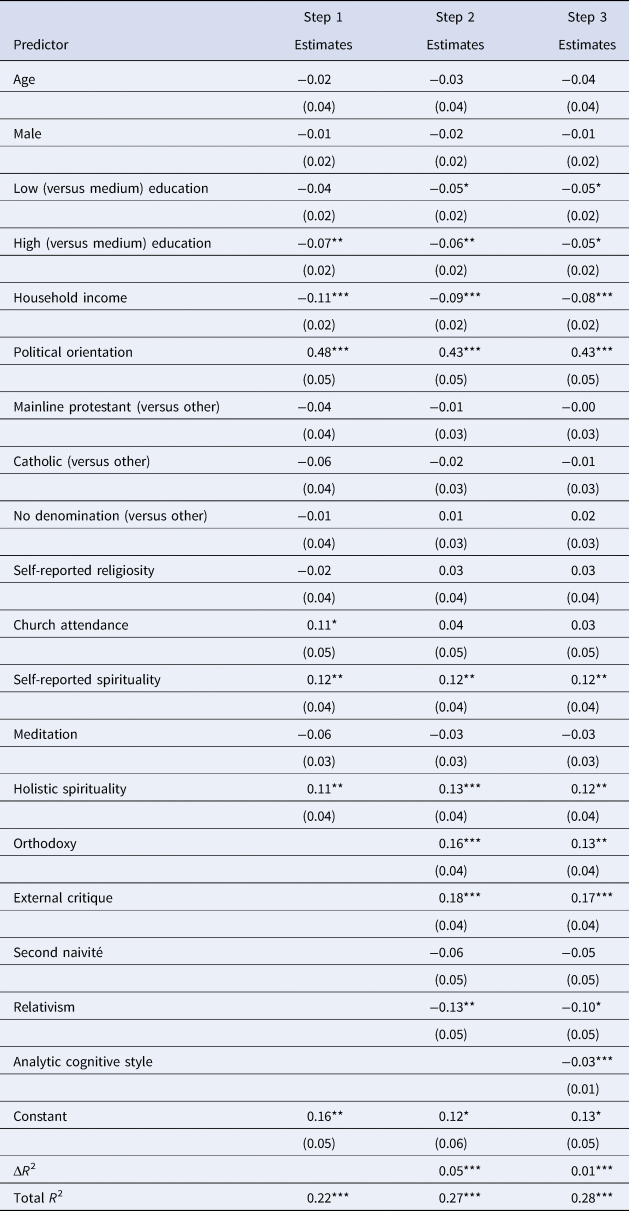

Table 2 reports the analysis results with beliefs in specific conspiracy theories as dependent variable. In the first step, sociodemographic, ideological, religious, and spiritual predictors accounted for 22% of the variance in specific conspiracy beliefs, R 2 = 0.22, F(14,816) = 20.97, p < 0.001. Those who reported a right-wing orientation, attending church more often and being more spiritual were significantly more likely to believe in conspiracy theories. Religious self-identification was not related to conspiracy beliefs. Of the remaining variables, we found that higher education and income significantly depress the endorsement of conspiracy theories.

Table 2. Multiple regression predicting specific conspiracy beliefs

Note: The entries are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients and robust standard errors in parentheses, N = 831. Continuous predictors are coded to range from 0 to 1.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The addition of post-critical beliefs in the second step significantly increased the variance accounted for by 5%, ΔR 2 = 0.05, F(4,812) = 13.43, p < 0.001. Confirming H1 and H2, orthodox religious beliefs and external critique increased susceptibility to conspiracy narratives. Contrary to H3, second naivité was unrelated to conspiracy beliefs. Relativism reduced the likelihood of accepting conspiratorial accounts of events, thus confirming H4. Individual religiosity was not significantly associated with conspiracy beliefs even without accounting for post-critical beliefs. However, church attendance was no longer a significant predictor of conspiracy beliefs. This suggests that orthodoxy explains the effect of religious commitment on specific conspiracy beliefs. In contrast, self-reported spirituality and holistic spiritual beliefs remained significant predictors of belief in conspiracy theories.

Entering analytic cognitive style in the third step increased the explained variance by an additional 1%, ΔR 2 = 0.01, F(1,811) = 13.77, p < 0.001. As expected, individual propensity to engage in analytic thinking is negatively related to conspiracy beliefs. Interestingly, literal interpretations of religious content (orthodoxy and external critique) and historic relativism were still significantly related to specific conspiracy beliefs which run counter to our expectations formulated in H5. We also observe that spiritual self-identification and beliefs were still positively associated with specific conspiracy beliefs. This suggests that the nature of religious information processing is not the mechanism explaining relations between spirituality and the propensity to endorse conspiracy theories, thereby contradicting H6.

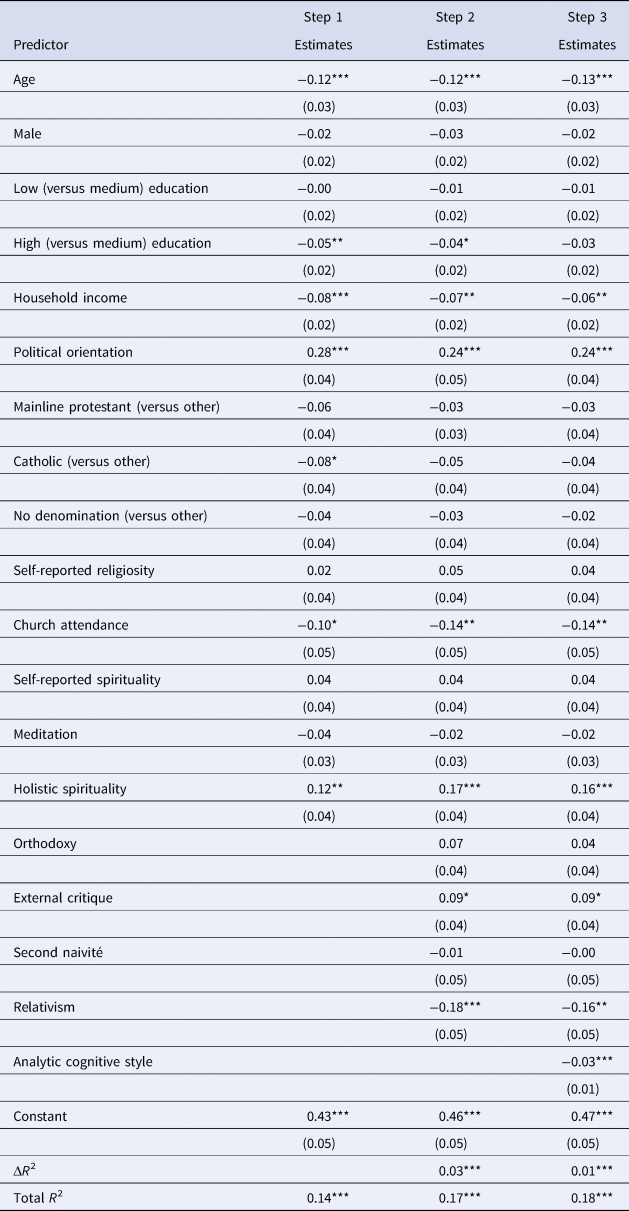

Table 3 reports the regression analysis results with a generalized conspiracy mentality as the dependent variable. Similar to specific conspiracy beliefs, sociodemographic, ideological, religious, and spiritual factors were significant predictors of conspiracy mentality, with 14% of the variance accounted for by these variables, R 2 = 0.14, F(14,816) = 10.92, p < 0.001. Individual religiosity was again unrelated to conspiracy mentality. However, surprisingly, the results suggested that attendance of religious service reduces belief in conspiracies as a worldview. Holistic spirituality but not self-reported spirituality is also a significant positive predictor of conspiracist thinking. Among the control variables, only participants with higher education, higher income, and an older age were less likely to exhibit a conspiracy mentality. By contrast, right-wing political orientations are positively correlated with general conspiratorial thinking.

Table 3. Multiple regression predicting conspiracy mentality

Note: The entries are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients and robust standard errors in parentheses, N = 831. Continuous predictors are coded to range from 0 to 1.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The addition of post-critical beliefs explained an additional 3% of the variation in conspiracy mentality, ΔR 2 = 0.03, F(4,812) = 6.71, p < 0.001. Hence, consistent with H2, a literal understanding of religious content in the form of external critique contributes positively to conspiracist thinking. Contradicting H1, orthodox beliefs were unrelated to conspiracy mentality. Moreover, a symbolic understanding of religious content in the form of relativist beliefs is negatively associated with conspiracy mentality, again providing evidence for H4. Spiritual beliefs also remain significant positive predictors when controlling for post-critical beliefs.

Analytic thinking accounted for an additional 1% of the variation in conspiracy mentality in the final step of the regression analysis, ΔR 2 = 0.01, F(1,811) = 12.44, p < 0.001. Contrary to our hypotheses H5 and H6, controlling for analytic thinking does not change the overall pattern of results. External critique and spiritual beliefs were still positively associated with conspiratorial thinking in general, while historical relativism was negatively associated providing further evidence for the robust effects of religious and spiritual attitudes on conspiracism.

Discussion

Although far-reaching secularization has taken place in modern Western societies, religion and religious beliefs still play an important role in many people's lives. In addition, different types of people are looking for alternative forms of religious expression and are turning to alternative spiritual belief systems. In the present study, we have explored how conventional religious beliefs and holistic spirituality are related to conspiracy beliefs and conspiracy mentality. We extended psychological approaches based on information processing by including Wulff's (Reference Wulff1997) model of attitudes toward religious information as a theoretical background. We have found that a literal interpretation of religious texts and teachings has a positive relation with belief in specific conspiracy theories—both for orthodoxy and external critique (e.g., the rejection of transcendental realities). Whereas orthodoxy is not related to conspiracy mentality, external critique is. So, a nonreligious literal interpretation of religious information is more consistently related to conspiracy thinking than its religious counterpart. In contrast, a symbolic understanding of religious information decreases the propensity to endorse conspiracy beliefs and mentality. However, this only applies to relativism, which excludes the existence of transcendence. Orthodoxy is only related to specific conspiracy beliefs but not to conspiracy mentality when control variables are included in the model.

Hence, our results suggest that it is less important whether one is religious or not, in the sense of including or excluding transcendence, than whether one interprets religious content more literally or symbolically. But paradoxically, the post-critical belief scale contributes more to the explanation of conspiracy beliefs and mentality of the non-religious. However, the results of our empirical analysis show no evidence for our general hypothesis that analytic cognitive style accounts for the relationship between religious attitudes, spirituality, and conspiracism. A literal understanding of religiosity as well as spiritual beliefs remain significant and substantial predictors of conspiracy beliefs and mentality after controlling for individual differences in analytic thinking. This pattern of results suggests that there are particular ways of dealing with religious information that are not captured by the CRT. Our findings underscore that the ways humans assess religious information—which includes a variety of sources such as scriptures or the teachings of religious communities—also influences the perception of other forms of transcendental narratives.

Accordingly, we argue that our study represents a first important step in extending the study of religion, spirituality, and conspiracy to specificities of religious information processing. The contributions of the present study to the ongoing literature are as follows. First, our study introduces a new approach to the religiosity and conspiracy beliefs literature. Our results indicate that it is not the similarity between religious belief systems and conspiracy beliefs (e.g., supernatural powers, salvation, or irrationality) that has produced the correlations in the survey (Keeley, Reference Keeley, Dyrendal, Robertson and Asprem2018). Instead, differences in religious information processing are more important for explaining conspiracy beliefs than the specific contents of beliefs. The positive effect of the literal exclusion of transcendental realities (e.g., atheism) supports this conclusion. A literal interpretation of religious information also positively correlates with conspiracy beliefs. This means that individuals excluding the existence of a religious transcendence will accept the truth of conspiracy narratives that often also include transcendental elements. This finding emphasizes the relevance of studying this relationship in terms of literal understandings of information about transcendental narratives because symbolic interpretations will require the historic and social contextualization of the narratives which will disadvantage information contested by truth making institutions.

Nevertheless, the relationships between religiosity and spirituality on the one hand and conspiracy thinking on the other hand remain complex. For holistic spirituality, we do not find evidence that literal interpretations of religious information shape their association with conspiracy beliefs frequently found in the literature. In theory, spirituality can also be associated with literal or symbolic interpretation of religious information and conceptually the PCBS covers this distinction. In very early writings about the holistic milieu, Champion and Hervieu-Lèger (Reference Champion and Hervieu-Léger1990) already reported the existence of fundamentalist forms of spirituality. Regarding our results, either the association extends from the similarity between holistic spirituality and conspiracy beliefs in terms of contesting the religious and political authorities producing it or the measurement in the post-critical belief scale does not capture literal interpretations within the context of holistic narratives of transcendence (see below). Regardless, our study extends the literature by introducing a measurement of holistic spirituality that focuses on holistic core beliefs, thereby overcoming the ambiguous measurements using a spiritual self-description that are highly correlated with Christian religiosity measures.

For conventional religiosity we find a relationship with conspiracy beliefs but not with conspiracy mentality contradicting recent findings published on Swiss data (Schwaiger et al., Reference Schwaiger, Schneider, Eisenegger and Nchakga2023). The effect of church attendance on conspiracy mentality is even negative. So paradoxically, orthodoxy is positively related to specific conspiracy beliefs confirming existing evidence that the strong and literal forms of beliefs are associated with conspiracy thinking (Łowicki et al., Reference Łowicki, Marchlewska, Molenda, Karakula and Szczepańska2022) but has no relationship with conspiracy mentality and church attendance even attenuates it. We agree with existing interpretations that religious practice fosters social integration through pro-social behaviors (Stavrova and Siegers, Reference Stavrova and Siegers2014) and trust (Valente and Okulicz-Kozaryn, Reference Valente and Okulicz-Kozaryn2021) thus immunizing to some extent against a general tendency of distrust in social and political institutions that is expressed in conspiracy mentality. The positive effect of orthodoxy on specific conspiracy beliefs contradicts the interpretation that opposition from church officials influences the adaptation of conspiracy narratives by churchgoers.

Second, our results inform the general discussion on conspiracy beliefs. Emphasizing the specificities of information on transcendental narratives in individuals' information processing might advance the research on conspiracy beliefs. Although our study confirms that analytic thinking is a significant predictor of conspiracy thinking, the PCBS has robust associations with conspiracy beliefs and mentality pointing to the particularities of religious attitudes compared to a purely rationlist approach. Moreover, religious institutions are among the most important “truth-making institutions.” Indeed, Christian churches in Germany are unlikely to be involved in spreading conspiracy narratives; for many topics—especially regarding public health and immigration—they explicitly contradict current conspiracy theories and provide pastoral workers with guidelines to counter conspiracy narratives.Footnote 2 Our study does not cover how informational cues from ecclesiastical authorities interact with literal and symbolic interpretations of religious information. The role of religious communities in shaping conspiracy thinking remains understudied probably because it requires complex research designs. Nevertheless, our findings underscore the need to systematically address the core characteristic of the contestation of authority and dominance in contemporary conspiracy narratives. Future studies might integrate perceptions of dominance into an approach focused on information processing, thereby extending the theoretical framework to the role of religious and spiritual communities and institutions.

Third, our research informs the ongoing discussion concerning holistic spiritualities in secular societies. Our analysis supports extant findings suggesting a stable relationship between holistic spirituality and conspiratorial beliefs (Schwaiger et al., Reference Schwaiger, Schneider, Eisenegger and Nchakga2023). These findings are relevant because proponents of secularization theory have repeatedly argued that even if holistic spirituality developed during secularization as an individualized alternative to Church-bound religiosity, it is not socially significant because it fails to sustain a distinct pattern of attitudes and behavior (Voas and Crockett, Reference Voas and Crockett2005; Voas, Reference Voas, Jupp and Flanagan2007). That is, holistic beliefs result when individuals draw from and mix different religious and spiritual sources. Their association with conspiracy beliefs also reveals that holistic spirituality shapes attitudes in a politically relevant domain. Accordingly, future research must address the potential political consequences of holistic spirituality more systematically before concluding that they are socially insignificant or stressing only the pro-social characteristics of the holistic milieu (Clot-Garrell and Griera, Reference Clot-Garrell and Griera2019). At the same time, our research calls for improved scales to study attitudes toward religious information within the holistic milieu. The distinction between literal and symbolic interpretations of transcendental narratives might also be relevant for holistic spirituality and could explain the correlations that our study has found.

Limitations

Some limitations of our research design are related to measurement and data quality. The measurement of the PCBS is biased toward traditional forms of Christian religiosity. Its item wording refers to core concepts of Christian beliefs (e.g., God, Bible, etc.). Therefore, the scale is valid for measuring Christian literalism but probably not for holistic literalism. As mentioned above, we do not expect that the scale in its current form would measure literal and symbolic interpretations of spiritual narratives as it does for conventional religiosity. The strong correlation between holistic spirituality and conspiracy beliefs that remained after the inclusion of the PCBS in the model might have resulted from the incapacity of the scale to measure literalism in the holistic domain. Future research would therefore benefit from a revised measurement of literalism information processing also valid for holistic spirituality.

Additionally, the sample used in the survey was not probabilistic, which might have introduced slight bias into the analysis. In particular, online access panels in Germany are slightly less religious than probabilistic samples. Quotas on demographic characteristics are intended to alleviate bias in the sample, but this is only possible for characteristics whose distribution in the population is known. Unobserved heterogeneity in the data can potentially lead to biases in the results, especially affecting weakly significant findings.

Conclusion

The present study has extended the literature on the relationship between religiosity and spirituality on the one hand and conspiracy beliefs on the other hand by introducing a novel approach for assessing religious information processing. Our results demonstrate that literal interpretations of religious information are positively related to conspiracy beliefs for religious individuals and individuals contesting the existence of any transcendental reality. The effects of holistic spirituality remain strong even when controlling for PCBS types of religious information processing. One explanation for this is that the scale is biased toward Christian beliefs. Developing a general measure for literal information processing might yield different results. Another explanation is that the similarity of conspiracy beliefs and holistic spirituality drives such associations. Moreover, objecting to authority in the religious or political domain might shape individuals' beliefs. Future research should therefore integrate the significance of power and dominance in alternative spiritual and political beliefs into information processing models to better explain the role of conspiracy beliefs in contemporary societies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048324000130.

Data

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available via PsychArchives at https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.14142.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Miriam Feldhausen for their assistance in preparing the data for the German General Social Survey. We are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers who provided insightful comments on earlier versions.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethics committee at GESIS—Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences (No. 2021-5a).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Alexander Jedinger is a Senior Researcher at GESIS—Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. His research lies at the intersection of political science and psychology, with a focus on the study of prejudice, conspiracy theories, political ideologies, and extremism.

Pascal Siegers is head of the Research Data Center German General Social Survey (FDZ ALLBUS) and co-team leader of National Surveys at the GESIS Data Archive in Cologne. Areas of research: sociology of religion and morality, quantitative religious research, new data types in social research, and research data infrastructures.