Are the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) being used in primary care?

Mental illness accounts for 40% of all disability in the United Kingdom and takes up at least one third of General Practitioners’ (GPs) time (Layard, Reference Layard2006). Demonstrably effective psychological treatments exist (Nathan and Gorman, Reference Nathan and Gorman2007) and are cost effective (Myhr and Payne, Reference Myhr and Payne2006). These are listed in the NICE guidelines. The NICE guidelines for OCD were published in 2005, soon after the guidelines for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and eating disorders (NICE, 2004; 2005a; 2005b). There has not been any research on whether NICE guidelines for OCD are being implemented in primary care; however, Ehlers et al. (Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009) found that only 15% of GPs reported that they had read the NICE guidelines for PTSD. Furthermore, a study conducted in 2007 found that only 4% of GPs used any guidelines for eating disorders (Currin et al., Reference Currin, Waller, Treasure, Nodder, Stone, Yeomans and Schmidt2007) in questionnaire-based studies. This contrasts with 60.3% of GPs reading the NICE guidelines for depression (Toner et al., Reference Toner, Snape, Acton and Blenkiron2010). An important additional finding was a low prevalence of PTSD in primary care in comparison with household prevalence estimates, leading to the conclusion that this disorder is under-recognised in primary care (Ehlers, et al., Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009).

OCD is characterised by either obsessions or compulsions, but commonly both (NICE, 2005a). The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) found OCD to have a prevalence of 1.1% in the United Kingdom (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins2009). However, a survey in the Netherlands suggests that the detection rates of OCD in primary care fall significantly short of estimated prevalence on the basis of household surveys (De Waal et al., Reference De Waal, Arnold, Eekhof and Van Hemert2004). This may be due to the fact that OCD is being under-diagnosed, misdiagnosed or because patients keep the disorder hidden from GPs (Newth and Rachman, Reference Newth and Rachman2001).

NICE recommend a course of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) including Exposure Response Prevention for patients with mild OCD (NICE, 2005a). For moderate OCD Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) or further CBT sessions are recommended; a combination of drug treatments with a course of SSRIs is recommended for severe patients. If patients still do not respond, then a different SSRI, clomipramine, or referral to a specialist multidisciplinary team is recommended.

The implications of failing to follow the NICE recommendations are that patients may not receive evidence-based interventions. There is some evidence that this is the case in OCD. The APMS found that 69% of respondents with OCD were not receiving any treatment and 10% received counselling, which is not recommended by NICE for OCD (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins2009). These findings imply that NICE guidelines for OCD are not being implemented but it is not known specifically whether GPs are aware of, have read or follow these guidelines.

The aims of this study were to: 1) assess whether GPs are aware of or have read the NICE guidelines for OCD (NICE, 2005a), 2) compare this with the results found for PTSD (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009) and depression (Toner et al., Reference Toner, Snape, Acton and Blenkiron2010) and 3) establish the prevalence of OCD in primary care.

Methods

This study was undertaken on all GPs (n = 795) and practice managers (n = 157) in Berkshire and Buckinghamshire in 157 General Practice surgeries listed on the National Health Service (NHS) choices website from April 2010 to June 2010. If the GPs did not reply to the questionnaire within 4 weeks, the larger practices were visited personally or telephoned.

This area was chosen as it was local to the investigators. Buckinghamshire and Berkshire have populations of approximately 479 000 and 839 187 people, respectively. Overall, both Buckinghamshire and Berkshire are relatively wealthy in comparison with the rest of the country, with the Gross Disposable Household Income per head reaching 32% and 16%, respectively, in 2009 (Office of National Statistics, 2011). The APMS (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins2009) showed that the prevalence estimates for OCD in the South East were slightly higher than the national prevalence estimates (1.2%).

The questionnaire used was based on that used by Ehlers et al. (Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009), facilitating an easy comparison between the results from this study and theirs. The questionnaire contained 19 items on two sides of A4 and took 5 min to complete. A questionnaire design was used as it is an economical method to reach a large sample and offers a cross-sectional view of GPs’ use of the NICE guidelines for OCD. GPs were asked whether or not they had read or were aware of the NICE guidelines for OCD, whether they had read guidelines for any mental health disorders or any non-mental health disorders and how many patients with OCD they had treated in their career and in the past 12 months. GPs were also asked to choose from a list of psychological treatments and state which drug treatments they typically prescribed for patients with OCD.

Binomial tests were used to compare the proportion of GPs who have read the NICE guidelines for OCD with the proportion of patients who have read the NICE guidelines for depression as reported by Toner et al. (Reference Toner, Snape, Acton and Blenkiron2010) and PTSD, as reported by Ehlers et al. (Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009).

In order to assess the prevalence of OCD in primary care, practice managers were asked to report the number of patients registered to their practice and the number of those who were listed as having OCD. This study was approved by the Berkshire NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC; ref: 10/H0505/6) and the University of Reading REC (ref: 09/70). Participants received an information sheet. There was no deception and all information was kept confidential and anonymous. The researchers were impartial to the subjects.

Results

Responses

Of the 795 questionnaires sent to GPs in Berkshire and Buckinghamshire, 80 were returned (10.1%). Of the 157 letters sent to practice managers, 30 were returned (19.1%). All respondents identified themselves as either partners in their practice or salaried GPs.

Awareness and reading of guidelines

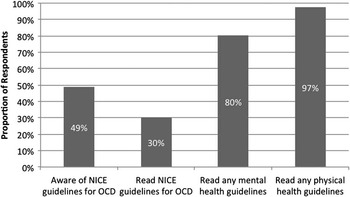

Figure 1 shows the proportion of respondents who have read and are aware of the NICE guidelines. A binomial test showed that significantly more GPs had read the NICE guidelines for OCD than PTSD (15%, from Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009; P = 0.001) and that there was no significant difference between the number aware of the guidelines for OCD and PTSD (55%; P = 0.161). Significantly fewer had read the NICE guidelines for OCD than the 97.4% who reported they had read a NICE guideline for a non-mental health condition (P < 0.001) and 80.3% reported having read a NICE guideline for a mental health condition (P < 0.001). Significantly fewer GPs had read the NICE guidelines for OCD than the 60.3% (Toner et al., Reference Toner, Snape, Acton and Blenkiron2010) found had read the NICE guidelines for depression (P < 0.001). Toner and colleagues did not collect data regarding awareness of the NICE guidelines for depression.

Figure 1 Results of GP survey about use of NICE guidelines

Treatments

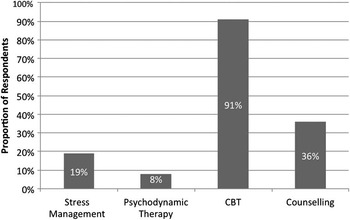

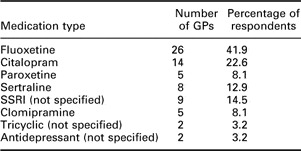

Figure 2 shows the psychological treatments that GPs report offering patients with OCD. GPs stated that they would offer CBT in 86.5% (SD = 24.36) of cases. GPs who reported reading the NICE guidelines for any mental health disorder were significantly more likely to offer CBT to their patients [χ 2(1) = 6.81, P = 0.025, Φ = 0.299] than those who had not. GPs reported that they would prescribe medication to 59.5% (SD = 27.17) of OCD patients. The medications prescribed are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2 Proportion of GPs who stated that they would offer these psychological treatments to patients with OCD

Table 1 Medications prescribed by GPs to patients with OCDFootnote a

GPs = General Practioners; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; SSRI = Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors.

a Respondents could give more than one answer.

Prevalence of OCD in primary care

The responses from the practice managers indicated that a mean of 0.22% (SD = 0.13) of patients registered to a practice were diagnosed with OCD, significantly lower than the national prevalence estimate of 1.1% [t(29) = 37.08, P < 0.001, d = 6.77] or the prevalence estimate for the South East of England [t(29) = 41.29, P < 0.001, d = 7.54] (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins2009). GPs who had read the NICE guidelines for OCD were also more likely to have seen more OCD patients in the past 12 months [t(74) = 1.73, P = 0.044, d = 0.404].

Discussion

This study found that 30.3% of GPs had read the NICE guidelines for OCD, twice the number that read the NICE guidelines for PTSD, but half the number who read the depression guidelines (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009; Toner et al., Reference Toner, Snape, Acton and Blenkiron2010). The finding that a large proportion of GPs (80.3%) had read NICE guidelines for any mental health disorders is encouraging. In line with the NICE guidelines, CBT was the most commonly offered psychological therapy and was offered more than psychotropic medication. An interesting finding was that GPs who had read the NICE guidelines for any mental health disorder were significantly more likely to offer CBT than those who had not. However, no such difference was found between GPs who had and had not read the NICE guidelines for OCD. This finding may reflect the fact that NICE recommends CBT for a wide range of mental health disorders.

The prevalence rate based on the responses from practice managers was 0.2%. Household surveys (NICE, 2005a; McManus et al., Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins2009) suggest that the prevalence is roughly 1.1–1.2%. This suggests that only one in five patients with OCD is detected in primary care. One explanation is that the failure to read NICE guidelines leaves some clinicians ignorant of the nature of OCD. OCD is heterogeneous and although typical forms such as excessive washing and checking may be easily detected, other forms such as mental rituals are less obvious. This would explain why GPs who reported that they had read the NICE guidelines had treated a greater number of patients with OCD in the past 12 months.

The low prevalence of OCD found in primary care could be because patients conceal their obsessions (Newth and Rachman, Reference Newth and Rachman2001). This may be because patients fear stigma. The perceived stigma of OCD has been found to be a barrier to seeking treatment (Marques et al., Reference Marques, LeBlanc, Weingarden, Timpano, Jenike and Wilhelm2010). This would explain the low prevalence of OCD in practices and why household surveys indicate that few patients with OCD in the UK receive any treatment (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins2009).

This study has several limitations. It has a low response rate and thus the representativeness of the sample may be questioned. However, the response rate was comparable to other researches undertaken on the topic (Currin et al., Reference Currin, Waller, Treasure, Nodder, Stone, Yeomans and Schmidt2007; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009). Another limitation arises from using a questionnaire, in that it does not allow GPs to reflect their attitudes and beliefs beyond the given format. Qualitative interviews would be a useful tool to corroborate these findings. The study was also undertaken in a relatively wealthy area and therefore the results from this study may not be representative of the rest of the United Kingdom. Further research into the use of NICE guidelines across England and Wales is required to investigate whether the wealth of an area is associated with the use of NICE guidelines or the treatments offered.

A further limitation of this research is that the stepped care approach was not investigated by this study. The stepped care approach is stressed by NICE for mental health disorders. By asking GPs to specify which treatments are offered to mild, moderate or severe patients with OCD, a better understanding of how OCD is treated in primary care can be reached. Follow-up studies should take this into account when investigating the use of NICE guidelines for mental health. GPs were not given a list of which conditions are considered mental health conditions by NICE; thus, it is possible that some respondents may have incorrectly reported that they had or had not read a NICE guideline for a mental health disorder.

In conclusion, this study indicates that the NICE guidelines for OCD are being read by a minority of GPs, although the majority of GPs are aware of them. Furthermore, the prevalence of OCD in primary care is significantly below estimates from epidemiological studies. Encouraging patients to seek treatment coupled with improving the recognition of OCD in primary care would be a step towards improving the implementation of NICE guidance for this disabling disorder.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kate Masters and Marion Walker for the help with the interpretation of the pharmacological data, Anna Coughtrey and Eleanor Ewan for comments on the first draft of this paper and Manda Branson and Eva Zysk for their support throughout this project. This research was undertaken as part of the first author's Master's degree in Research Methods in Psychology at the University of Reading. This formed part of Medical Research Council–Economic and Social Research Council Interdisciplinary Studentship entitled: ‘Increasing the implementation of evidence-based treatments for mental health’. This study has been approved by both the Berkshire NHS Research Ethics committee (reference no: 10/H0505/6) and the University of Reading Research Ethics Committee (reference no: 09/70).