What’s new

Based on a review of a large and demographically varied sample, this research documents a high burden of chronic disease and chronic medical complexity in pediatric primary care and the significant correlation between chronic medical and mental health conditions.

Introduction

Patients with chronic health problems are among the most expensive group of patients to care for in any health system. As a group, they sustain the highest costs and highest rates of hospitalization (Moffat and Mercer, Reference Moffat and Mercer2015).

The proportion of patients presenting to the pediatric primary care setting with chronic illness and multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of two or more health problems is growing (Uijen and van de Lisdonk, Reference Uijen and van de Lisdonk2008; Pefoyo et al., Reference Pefoyo, Bronskill, Gruneir, Calzavara, Thavorn, Petrosyan, Maxwell, Bai and Wodchis2015). In part, this has been attributed to advances in medical and rehabilitative management, allowing children with increasingly severe conditions to survive to older ages. Other trends that may contribute include increased rates of obesity and other chronic conditions that include allergic diseases as well as behavioral and mental health conditions (Branum and Lukacs, Reference Branum and Lukacs2009; Perou et al., Reference Perou, Bitsko, Blumberg, Pastor, Ghandour, Gfroerer, Hedden, Crosby, Visser, Schieve, Parks, Hall, Brody, Simile, Thompson, Baio, Avenevoli, Kogan and Huang2013).

These factors have driven the need for delivery of increasingly complex care in the outpatient setting. Polypharmacy, coordination with specialists and social services, lack of evidence-based guidelines for treatment of concurrent conditions and difficulty in prioritizing treatments are just some of the challenges that physicians encounter in dealing with patients with chronic disease and multimorbidity. Reports suggest that generalists encountering patients with multimorbidity experience greater workloads, time pressure and feelings of frustration (Sondergaard et al., Reference Sondergaard, Willadsen, Guassora, Vestergaard, Tomasdottir, Borgquist, Holmberg-Marttila, Olivarius, de and Reventlow2015; Foster et al., Reference Foster, Mangione-Smith and Simon2017). It is also increasingly clear that the association of chronic disease and psychosocial issues represent a major barrier to the successful management of patients in the primary care setting, and create additional burdens for providers (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Atlas, Hong, Ashburner, Zai, Grant and Hong2017).

Although the awareness of the prevalence and impact of multimorbidity is increasing, few studies on the prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care populations have included patients in the pediatric age range (Schellevis et al., Reference Schellevis, van der Velden, van de Lisdonk, van Eijk and van Weel1993; Britt et al., Reference Britt, Harrison, Miller and Knox2008; Uijen and van de Lisdonk, Reference Uijen and van de Lisdonk2008; van Oostrom et al., Reference van Oostrom, Picavet, van Gelder, Lemmens, Hoeymans, van Dijk, Verheij, Schellevis and Baan2012). Most studies have calculated population prevalence rates using a pre-specified list of common chronic illnesses. These lists tend to be limited and skewed toward common problems that impact adult populations, such as coronary artery disease or hypertension. In addition, previous studies have not included psychosocial problems. In pediatric practice, conditions such as homelessness or abuse are particularly important because they often represent high levels of vulnerability to harm and so require active and ongoing monitoring and management. Often, dealing with these problems and their attendant dysfunctions are as challenging as dealing with complex medical problems. Likewise, problematic family dynamics or personality issues may complicate medical management. These are often not readily amenable to individual or multidisciplinary solutions (Campo et al., Reference Campo, Jansen-McWilliams, Comer and Kelleher1999; Kellogg et al., Reference Kellogg, Hoffman and Taylor1999; Radovic et al., Reference Radovic, Reynolds, McCauley, Sucato, Stein and Miller2015).

Attempts to estimate the numbers of children with any chronic disease in the United States have been hampered by inconsistency in the populations and settings studied, methods of recruitment, data collection and definitions utilized. These studies are further limited by the use of billing information to identify clinical complexity. In primary care, billing codes or scoring systems are often used as a proxy for the time and effort expended on patient care. However, coding data and commonly used scoring or risk adjustment systems designed for single illness paradigms may not accurately capture the complexity of health delivery in this setting (Horner et al., Reference Horner, Paris, Purvis and Lawler1991; Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Hutchison, Norman, Brown and Abelson1998; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Ashburner, Hong, Chang, Barry and Atlas2011; Cederna-Meko et al., Reference Cederna-Meko, Ellens, Burrell, Perry and Rafiq2016; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Atlas, Hong, Ashburner, Zai, Grant and Hong2017). The variability in disease definitions and populations is reflected in the wide range of estimates of chronic disease reported in a recent meta-analysis, which reported rates of chronic disease of 0.5–44% in various studies (van der Lee et al., Reference van der Lee, Mokkink, Grootenhuis, Heymans and Offringa2007). Surveys that have used stricter criteria to identify the subset of children with the most severe or catastrophic forms of chronic disease [usually defined as those requiring constant care or the use of technology to sustain life or maintain health – which we define as Catastrophic Medical Complexity (CMC)] have estimated a prevalence in the population of <1% (Stein and Silver, Reference Stein and Silver1999).

The delivery of primary care is unique in that it is influenced by a very wide range of interpersonal, medical, psychosocial and systems issues that often must be taken into account when making a diagnosis, planning care coordination, providing treatment, education or arranging follow-up (Sussman et al., Reference Sussman, Williams, Leverence, Gloyd and Crabtree2006). The coexistence of more than one medical condition or the co-occurrence of medical and behavioral or psychosocial conditions increases the complexity of medical decision making and/or the visit duration (Foster et al., Reference Foster, Mangione-Smith and Simon2017). With this in mind, the aim of this study was to characterize the burden of chronic disease in the pediatric primary care setting using input from front-line primary care providers. Feedback from those clinicians providing the care is important, since the complexity experienced in primary care is not fully captured by historical costs, billing data or other administrative information.

A secondary goal of the analysis was to determine if the prevalence of patients with chronic conditions differed by patient demographic characteristics or by the location of the site where care delivery occurred, in an academic versus community clinic.

Methods

Research design and patient population

We conducted a retrospective review of electronic medical records (EMR) of 3998 randomly selected patients seen in two general pediatrics clinics between June 2015 and May 2016. The two clinics are part of the same practice group with a common EMR (Epic). One of the clinics is an academic ambulatory pediatric clinic located on the campus of a quaternary medical center, and the other a community primary care office in a suburban location.

A computer-generated random sample of 1999 unique medical record numbers (MRN) was generated from each clinic for a total of 3998 records. Data obtained from the EMRs included age, sex, insurance status, language and the problem list of each patient. Three medical records that had no patient data associated with the MRN were excluded from the analysis. The sample size was calculated to power the study to detect a significant difference in the number of patients with CMC, between the two clinic sites.

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Nebraska Medical Center reviewed and approved the study protocol.

Chronic disease definition

A list of chronic disease categories was generated by the research team based on review of the problem lists of the sample population (Table 1). Conditions were included in the chronic disease categories if they were chronic, and were judged by the group to require attention that might include treatment, care coordination, medication management and education over time. These included chronic physical, mental health and social problems that are commonly encountered in primary care practice.

Table 1 Chronic disease categories

ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; PTSD=Posttraumatic stress disorder; OCD=obsessive compulsive disorder; HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; TB=tuberculosis; BMI=body mass index; ACTH=adrenocorticotropic hormone; ENT=ear nose and throat; GI=gastrointestinal; IgA=immunoglobulin A; CSF=cerebrospinal fluid; CPAP=continuous positive airway pressure.

Diagnostic categories were then assigned to each diagnosis on the problem list of the sample data. The initial category assignment was independently performed by two of the investigators, then compared with ensure consistency. The final categorization of the entire data set was then reviewed by the primary investigator for consistency.

Additionally, the review identified patients who met criteria for CMC defined as children with one or more conditions resulting in severe disability, needs for intensive home care, chronic disease management and specialty care, and in most cases, reliance on medical technology for survival. As with the diagnostic categories above, designation as severe medical complexity was also performed by two of the investigators independently; the results were subsequently compared for consistency, then reviewed and confirmed by the group.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the demographic variables of the sample population. Bivariate analyses were used to compare the patients’ demographic information at each of the two clinic locations. Next, distribution of the number of complex conditions was examined using χ 2 tests for categorical variables and comparing medians and interquartile ranges for numeric variables. Finally, a multinomial logistic regression was conducted, which modeled the relationship between the number of chronic medical problems and the number of psychosocial/behavioral problems, while controlling for the effect of age, sex, insurance status, primary language and clinic location.

In this analysis, the outcome variable was the number of chronic complicating medical problems (none, one to two, three to five or more). The model covariates included the presence of a psychosocial or behavioral diagnosis (any versus none), age group (0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–8, 9–11, 12–15, 16+ years), sex, insurance (private, public, uninsured), language (English, Spanish, other) and clinic location (academic versus community). Data analysis was conducted in Stata 14.2.

Results

A total of 3995 pediatric patients EMRs were included in this analysis. Demographic characteristics of patients are presented in Table 2. Patients from the academic clinic were more likely to be younger, less likely to identify English as the primary language of the family (P<0.001) and more likely to have public or no insurance (P<0.001). Patients with public insurance had a higher rate of having one or more or chronic medical problems relative risk ratio (RRR): 1.41 (1.17, 1.70) and 1.78 (1.26, 2.53), respectively. Similarly, being uninsured conferred higher risk of having one or two chronic medical problems RRR: 1.95 (1.12, 3.40).

Table 2 Participant characteristics

At the bivariate level, there was a significant relationship between insurance status and the number of chronic medical problems (χ 2=17.05, P=0.009). Privately insured patients were less likely to have any chronic medical condition than patients who were either uninsured or publicly insured (χ 2=11.218, P=0.001). Patients who were publicly insured were more likely to have one or more chronic complicating medical conditions than patients with private insurance or no insurance (χ 2=9.74, P=0.002). There was no relationship between being uninsured and the presence of any chronic complicating medical problems. Male patients were more likely to have 1–2 and 3–5 chronic conditions [1.22 and 1.30 times, respectively, (1.07, 1.40) and (1.01, 1.68), respectively). Finally, older patients tended to have significantly more chronic conditions than younger ones.

The distribution of the number and types of chronic conditions are presented in Table 3. More than half (52.6%) of patients in the total sample had at least one chronic condition. In total, 25% had two or more chronic conditions. The proportion of children who had 1–4 chronic conditions was similar in the academic and community clinics. There was a significantly higher proportion of patients with five or more chronic conditions at the academic clinic compared with the community clinic (P=0.013). The academic clinic also has significantly more patients who had CMC than the community clinic (P<0.001).

Table 3 Distribution of the number of chronic conditions

Chronic conditions

The frequencies of chronic conditions are shown in Table 4. Conditions identified in Table 1 with a frequency of <2% were classified under the category of ‘Other’ in Table 4.

Table 4 Distribution and frequency of chronic condition types by clinic location

ADD=attention deficit disorder; ADHD=Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Categories are not mutually exclusive and do not sum to 100%.

The most frequent single diagnosis was obesity, at 13.5% of the total sample and slightly more frequent in the community clinic population (Table 4).

Asthma was the second most common single diagnosis at (12.4% of the total sample). While this average is higher than the most recent national asthma prevalence of 9.5% in children, this is likely due to the higher prevalence of this illness in the academic clinic population (15.6%). Allergic rhinitis and eczema were reported in 10.7% and 9.5% of cases, respectively. Eczema was significantly more prevalent in the academic clinic population. However, food allergies were reported three times more frequently in the community clinic population.

There was no difference in the prevalence of developmental delay or autism between the two locations. The prevalence of autism was slightly lower in our sample (0.6%) than national (1.5%) and state (0.9%) estimates.

Overall, 3.1% of the total sample met criteria for CMC. The academic clinic had significantly more patients classified as CMC (3.9%) than the community clinic (2.3%) (P<0.001). These numbers are higher than previous community estimates of <1%.

Behavioral and mental health diagnoses

Mental health problems were on the problem list of 12.3% patients in the total sample. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was the most common behavioral diagnosis. ADHD and anxiety were diagnosed twice as commonly in the community clinic population.

Chronic disease and psychiatric comorbidity

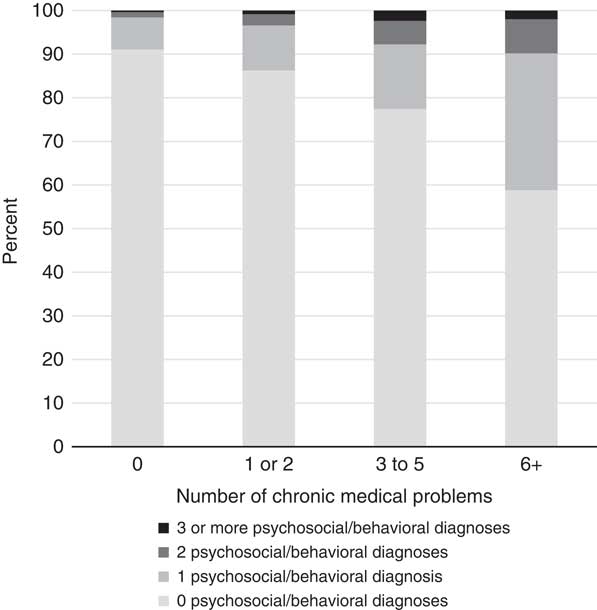

There was a positive correlation between the number of chronic medical conditions and the number of psychiatric conditions (Figure 1). Patients with one psychosocial or behavioral diagnosis were 1.38 times more likely to have one or two medical problems, holding all other model covariates constant (95% CI: 1.11, 1.72). Similarly, having any psychosocial or behavioral diagnosis increased the likelihood of having three to five chronic complicating medical problems by 2.15 times (95% CI: 1.55, 2.98). Likewise, the presence of any psychosocial or behavioral diagnosis is associated with 5.83 times the risk of having six or more chronic complicating medical problems, holding all other model covariates constant (95% CI: 2.93, 11.57).

Figure 1 Relationship between chronic medical and psychosocial/behavioral diagnoses

DISCUSSION

We found that the majority (52.6%) of children in our primary care sample had a chronic condition, and that one in four patients met the definition of multimorbidity. Previous studies of outpatients that included subjects in pediatric age groups have reported rates of chronic illness that varied between 10% and 28% (Schellevis et al., Reference Schellevis, van der Velden, van de Lisdonk, van Eijk and van Weel1993; van den Akker et al., Reference van den Akker, Buntinx, Metsemakers, Roos and Knottnerus1998; Uijen and van de Lisdonk, Reference Uijen and van de Lisdonk2008; Britt et al., Reference Britt, Harrison, Miller and Knox2008; van Oostrom et al., Reference van Oostrom, Picavet, van Gelder, Lemmens, Hoeymans, van Dijk, Verheij, Schellevis and Baan2012; Brett et al., Reference Brett, Arnold-Reed, Popescu, Soliman, Bulsara, Fine, Bovell and Moorhead2013). However, by consulting with primary care pediatricians to expand the diagnoses included in the definition of chronic conditions, this study provides a broader perspective on the diversity and complexity of pediatric chronic disease.

Our results also demonstrated a link between medical and psychosocial problems. Patients with psychological or psychiatric conditions were more likely to suffer from multimorbidity, and vice versa. One previously published study in adults did not find a relationship between mental health conditions and multimorbidity (Fortin et al., Reference Fortin, Stewart, Poitras, Almirall and Maddocks2012), while another, larger study that included subjects in the pediatric age group reported a significant correlation (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Mercer, Norbury, Watt, Wyke and Guthrie2012). In addition, having no insurance or public insurance predicted increased numbers of chronic health conditions among patients in our sample. This was consistent with previous research linking increased chronic disease with lower socioeconomic status and deprivation (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Mercer, Norbury, Watt, Wyke and Guthrie2012; McLean et al., Reference McLean, Gunn, Wyke, Guthrie, Watt, Blane and Mercer2014; Violan et al., Reference Violan, Foguet-Boreu, Flores-Mateo, Salisbury, Blom, Freitag, Glynn, Muth and Valderas2014; Pulcini et al., Reference Pulcini, Zima, Kelleher and Houtrow2017).

The academic clinic served significantly more children with CMC, and more patients with greater than five comorbid chronic conditions than did the community clinic. These differences may be due to differences in ethnic, socioeconomic or environmental variables. The higher prevalence of patients with catastrophic medical conditions and comorbidity in the academic clinic could also be related to its location on the campus of a quaternary medical center in proximity to specialized services.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we relied of data from the EMR problem list. A potential disadvantage of this strategy is that the list must be maintained by providers and kept up to date. In addition, it was generally not possible to assess the severity of medical conditions from the problem list. However, severity scales utilized to assess chronic illness in other studies such as the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale have not been validated in pediatric populations. In addition, there are data suggesting that simple disease enumeration or medication counts perform almost as well as severity scales in predicting many outcomes (Huntley et al., Reference Huntley, Johnson, Purdy, Valderas and Salisbury2012).

Although the data were collected from two clinic populations that differed fundamentally in demographic characteristics, both clinics were part of the same practice plan within the same geographic boundaries of a single metropolitan area. This may limit generalizability of the data.

When developing strategies and resource allocation in care delivery redesign, it is important to ensure that the data that underpin the strategy reflect closely the clinical setting in which they will be implemented. This study differs from previous studies of multimorbidity in that it focuses exclusively on a pediatric primary care population, includes problems salient to pediatric primary care practice and relies on practicing primary care clinicians to determine which problem list diagnoses were included in the count of chronic conditions. We believe that these factors enhance the relevance and applicability of the data to the pediatric primary care setting.

Conclusions

Chronic disease, especially multimorbidity has traditionally been considered to be unusual in the pediatric age group. In this primary care sample, we found that chronic conditions and multimorbidity were encountered commonly.

The optimal management of chronic illness and multimorbidity requires a paradigm shift in the way that the health care delivery system operates. Currently, most medical systems are designed to address single conditions. However, this often does not reflect the reality in which the primary care physician reckons with the complex interplay between multiple conditions and their effects on the overall well-being of the patient and family. Inappropriate resource allocation resulting from the underestimation of the intensity involved in caring for these populations may lead to inappropriate resource allocation. This in turn may result in undesirable outcomes that may include suboptimal management, physician burnout, unnecessary testing and referral, and family and patient dissatisfaction. Future research that further quantitates both the overall impact of chronic disease and the contribution of specific components of individual cases on the care burden may lead to more appropriate resource targeting. Better understanding the true burden of morbidity and complexity will help systems to develop innovative and effective approaches to caring for these patients. This in turn could result in improved outcomes and decreased resource use for this group of patients.

Financial Support

Funding for this research was provided by the Department of Pediatrics, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Acknowledgments

None.