Introduction

Every year, 1.6 million adults in the United Kingdom develop back pain that will continue for more than three months (Department-of-Health, 2009), and approximately 20% of these adults will consult their general practitioner (GP; NICE, 2009). Persistent non-specific low back pain (PLBP), defined as back pain ‘for which it is not possible to identify a specific cause’ (NICE, 2009), accounts for a huge part of the daily workload in general practice, and the potential benefits of improving its management are significant (Croft et al., Reference Croft, Peat and Van-der-Windt2010). The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2009) recommends that decisions about care and treatment of PLBP should be made in partnership between the patient and their clinician (NICE, 2009). However, this partnership can pose a challenge (Corbett et al., Reference Corbett, Foster and Ong2009) even when clinicians accept best practice guidelines in theory, it can be difficult to implement guidelines in the face of patient preference. For example, although qualitative research shows that patients with PLBP continue to pursue diagnostic tests (Osborne and Smith, Reference Osborne and Smith1998; Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Ekholm and Ohman2004; Nettleton, Reference Nettleton2006; Toye and Barker, Reference Toye and Barker2010), guidelines recommend that doctors do not routinely offer X-rays and magnetic resonance imaging scans (NICE, 2009). The quality of the relationship between a patient and their GP can have important health implications and has received considerable interest (Ong et al., Reference Ong, Dehaes, Hoos and Lammes1995). The complexity of the clinician–patient relationship has been highlighted by Ong and Hooper, who describe concordance or discordance between a clinician and a patient, as a process that must be continually negotiated in the clinic (Ong and Hooper, Reference Ong and Hooper2006).

Qualitative findings suggest a lack of concordance in explanatory models used by patients with back pain and their clinicians. In particular, patients tend to strive for a medical explanation (Jackson, Reference Jackson1992; Eccleston et al., Reference Eccleston, Williams and Rogers1997; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Holloway and Sofaer1999; Glenton, Reference Glenton2003; Lillrank, Reference Lillrank2003) and reject psychosocial explanations (May et al., Reference May, Allison, Chapple, Chew-Graham, Dixon, Gask, Graham, Rogers and Roland2004; Allegretti et al., Reference Allegretti, Borkan, Reis and Griffiths2010). This lack of concordance is likely to have an effect on the relationship between a GP and a patient. If a person considers disease to have a medical explanation, he or she is likely to continue seeking a medical diagnosis and reject the best practice guidelines (NICE, 2009). Kleinman describes explanatory models in medicine as the way in which different groups categorise, interpret and treat illness (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1988). For example, the biomedical model assumes that disease is reducible to a specific somatic cause, independent of social, psychological or moral factors (Engel, Reference Engel1977). This model infers the dualism of mind and body, a specific aetiology and the curability of disease (Foucault, Reference Foucault1973; Engel, Reference Engel1977; Lupton, Reference Lupton1994; Bendelow and Williams, Reference Bendelow and Williams1995; Annandale, Reference Annandale1998; Helman, Reference Helman2007). In contrast, the biopsychosocial model focuses on the ‘human experience’ of illness (Engel, Reference Engel1977) regarding persistent pain as a result of a complex relationship between physical and psychosocial factors (Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Linton and C1998). Treatment approaches using the biopsychosocial model are being successfully used to help patients with PLBP (Morley et al., Reference Morley, Eccleston and Williams1999; Guzmán et al., Reference Guzmán, Esmail, Karjalainen, Malmivaara, Irvin and Bombardier2001).

Studies have shown that patients with PLBP pain remain committed to the biomedical model (Osborne and Smith, Reference Osborne and Smith1998; Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Ekholm and Ohman2004; Nettleton, Reference Nettleton2006; Holloway et al., Reference Holloway, Sofaer-Bennett and Walker2007), even though this model does not fit their pain experience (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1978; Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Danielson and Norberg1999; Vroman et al., Reference Vroman, Warner and Chamberlain2009). This may be related to a perceived need to legitimise PLBP (Parsons, Reference Parsons1951; Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1988; Good, Reference Good1994). Qualitative research shows us that patients with PLBP often feel stigmatised (Good, Reference Good1992; Jackson, Reference Jackson1992; Honkasalo, Reference Honkasalo2001; Glenton, Reference Glenton2003; Lillrank, Reference Lillrank2003; Osborne and Smith, Reference Osborne and Smith2006; Holloway et al., Reference Holloway, Sofaer-Bennett and Walker2007) and work hard to legitimise their condition in the face of scepticism (Osborne and Smith, Reference Osborne and Smith1998; Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Danielson and Norberg1999; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Mcphillips-Tangum, Markham and Klenk1999; May et al., Reference May, Rose and Johnstone2000; Werner and Malterud, Reference Werner and Malterud2003; Werner et al., Reference Werner, Isaksen and Materud2004; Miles et al., Reference Miles, Curran, Pearce and Allan2005; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Sofaer and Holloway2006; Toye and Barker, Reference Toye and Barker2010). The tension between two opposing explanatory models (biomedical and biopsychosocial) is made increasingly problematic for patients because of the associated cultural polarity between reality (body, medical, rational, fact, visible, knowing), and unreality (mind, psychosocial, irrational, belief, invisible, believing) (Good, Reference Good1994; Kugelman, Reference Kugelman1999). The danger for the patient of embracing a biopsychosocial model is that it can force patients to admit that pain is ‘in your head’ (Kugelman, Reference Kugelman1999). Medical diagnosis thus continues to be culturally legitimising (Good, Reference Good1994), and this continues to be a problem for both the GP and the patient who find themselves caught between two explanatory models.

Although patient-centred care has come to be associated with concordance between patient and GP, several authors have considered the ‘downside’ (Ong and Hooper, Reference Ong and Hooper2006) of a concordant relationship (Chew-Graham and May, Reference Chew-Graham and May2000; May et al., Reference May, Allison, Chapple, Chew-Graham, Dixon, Gask, Graham, Rogers and Roland2004; Ong and Hooper, Reference Ong and Hooper2006), and question whether concordance necessarily leads to improved patient care (May et al., Reference May, Allison, Chapple, Chew-Graham, Dixon, Gask, Graham, Rogers and Roland2004). Chew-Graham and May (Reference Chew-Graham and May2000) suggest that the problem of persistent back pain may even begin with the clinician's need to sustain a ‘continuing inclusive relationship’ with the patient. In particular, maintaining concordance may lead to the inappropriate use of health care and inequality of care for those who are less able to establish an effective relationship with their GP. For example, although it is clear that X-ray findings are not a clear indicator of back pain symptoms (Tulder et al., Reference Tulder, Assendelft, Koes and Bouter1997), and are against the recommended clinical treatment guidelines for patients with PLBP (NICE, 2009), what does a GP do if this is the patient's preference? Is there still a therapeutic advantage of referring for a diagnostic test when there is no known diagnostic test (Tulder et al., Reference Tulder, Assendelft, Koes and Bouter1997), if it reassures the patient?

Croft et al. (Reference Croft, Peat and Van-der-Windt2010) suggest that a change in the conceptual models of care would improve the outcome for patients with musculoskeletal pain, in particular, to move away from the focus on pathology and move towards the experience of symptoms and the impact of psychosocial factors. This requires a shift in the explanatory model away from the biomedical towards the biopsychosocial (Engel, Reference Engel1977). However, although the suggested shift in explanatory model for PLBP is timely, it is inherently difficult to challenge the prevailing model (Good, Reference Good1994). Importantly, this challenge may threaten concordance in the relationship between GP and patient.

The aim of the study was to explore how patients with PLBP interpret and utilise the biopsychosocial model in the context of pain management. Although not the main focus of the study, we found that all patients discussed their ongoing relationship with their GP. This paper presents findings regarding patients’ experience of general practice in relation to their PLBP. Additional conceptual analysis of this study focusing on patients’ struggle to legitimise PLBP has been published elsewhere (Toye and Barker, 2010).

Method

We obtained permission from the local research ethics council (REC) to undertake this research (REC reference 04/Q1605/99).

Sample

We wanted our sample to include patients who had experienced a range of treatments, and therefore sent a letter of invitation to all patients with PLBP attending a chronic pain management programme at one hospital between January and March 2005 (n = 29). This considered a large number of participants to be involved in an in-depth qualitative study (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). Qualitative research uses non-probability sampling of small groups of people to gain an ‘insight into a particular experience’ (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). We were certain from our experience and familiarity with the qualitative literature on pain that this number would allow adequate theoretical saturation (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). The letter of invitation included an information sheet providing details of the aims of the study and the involvement required. Patients were informed that they could see a copy of their interview and withdraw permission to use their interviews at any time. Patients attending pain management programmes had already been in contact with a wide range of health professionals and therapists over several months or years, and their symptoms have not responded to treatments. They are referred to the programme from various tertiary sources (eg, rheumatologists, orthopaedic surgeons, rehabilitation physicians, pain clinics), having initially been referred to hospital by their family doctor. Each programme includes up to eight people who attend nine sessions facilitated by a physiotherapist. The programme adopts a biopsychosocial approach that aims to help patients find ways of managing their pain, improve their confidence, gain an understanding of their pain and enjoy a better quality of life. Patients have the option to attend either once a week for nine weeks, or for three sessions a week over three weeks, depending on their individual circumstances. The programme consists of a series of group discussions, along with exercise and relaxation sessions. Discussions cover topics such as how to increase activity by pacing, how to exercise safely, understand why pain persists, relaxation, the need for a good night sleep, medication, exploring common worries and concerns, the role and limitations of medical investigations and planning for possible set backs. The programmes exclude non-English speakers who would be unable to participate in group discussions. To provide descriptive information, the Oswestry low back pain disability index was recorded for each patient. This is a measure routinely used in the programme to determine functional limitation (Fairbank, Reference Fairbank2000). It is scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating lower function. Patients' sex, age and Oswestry Index are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Patient sex, age and Oswestry disability index scores

Interviews

We conducted semi-structured interviews at three stages: before attending the course, immediately following the course and at one year after attending the course, yielding a total of 60 interviews. Patients were able to choose where they were interviewed. All chose to be interviewed at their home, where they would feel more at ease, and so that interviews could take place at their convenience. Every attempt was made to create rapport, and it was made clear that agreeing to be interviewed would not affect their treatment. An interview schedule was used very flexibly and only as a prompt (Table 2), and patients were encouraged to talk about the things that they thought were important to their pain experience. Topics covered in the interview schedule included the history of their pain experience and treatments, the effect of pain on their lifestyle, the cause of pain, their thoughts about the future and experience of other people with persistent pain. The aim was to gain an in-depth insight into what it is like for a person to have PLBP. The semi-structured format is a useful approach in research exploring personal meanings (Smith, Reference Smith1995; Fontana and Frey, Reference Fontana and Frey2000). Each interview lasted for approximately one to two hours and was tape-recorded. A central feature of grounded theory is that analysis does not follow data collection but is simultaneous to data collection. Each interview was transcribed and analysed before completing the next, so that subsequent interviews could be shaped by evolving theory.

Table 2 Interview prompts

Analysis

We used the methods of constructivist grounded theory as proposed by Charmaz (Reference Charmaz2006) to analyse the data. This philosophical framework was appropriate to the study and methodological standpoint of the research team, because it recognises that meaning arises out of social interaction and is modified by interpretation. We also aimed to present a conceptual analysis, grounded in the data, which could be transferable beyond the specific sample. Each transcript was listened to, transcribed verbatim and read several times to become familiar with the accounts. Early coding began by using low inference descriptors (Seale, Reference Seale1999) to summarise each unit of meaning within the interviews. Low-inference descriptors use patients’ own words or specific actions as initial codes, and therefore avoid theoretical interpretations too early in the analysis (Seale, Reference Seale1999; Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). As the coding develops, constant comparison of initial codes is carried out to develop conceptual themes by making theoretical connections (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). Throughout the analysis, constant comparison of transcripts, initial codes and later conceptual codes are used to develop progressively higher conceptual categories. To explore the properties of developing categories, we kept memos in a diagrammatic form similar to clustering (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006: 86), and modified these diagrams throughout the analysis, always returning to the initial interview data. We also used deviant-case analysis to constantly challenge emerging theory (Seale, Reference Seale1999: 75). This is a method that specifically looks for cases that challenge arising themes. A deviant case is found when the data does not fit with developing theory. Because of the volume of data, we used QSR International's NVivo (version 2.0) qualitative data analysis software to assist in the data analysis.

Although multiple ways have been suggested for determining the rigour of qualitative research, in recent years the emphasis has shifted from specific methodological criteria to a more interpretive form of rigour, that is, how do I know that I can trust this interpretation (Altheide, Reference Altheide and Johnson1994; Smith, Reference Smith and Deemer2000). Interpretive rigour is particularly important in health care, where findings can have an important impact on practice. Although interpretive grounded theory acknowledges that research offers an interpretation of findings (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006), we have used accepted means of justifying our interpretation. First to ensure that our analysis is grounded in the patients’ accounts, we used low-inference indicators (Seale, Reference Seale1999), constant comparison (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006) and negative case analysis (Seale, Reference Seale1999). We also included verbatim examples of transcripts to allow the reader to judge the quality of our chosen ‘concept indicators’ (Seale, Reference Seale1999). Collaborative interpretation is also an accepted means of ensuring rigour, that is, another person involved in the analytic decisions. This does not aim at convergence on a particular truth, however, contributes to what Seale refers to as ‘a self-questioning methodological awareness’ inherent in good-quality research (Seale, Reference Seale1999). Independent researcher coding is not always practical nor integral to qualitative research methods (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). In our study, KB questioned and commented on FT's coding and interpretation throughout the research process. Importantly, in addition to this, as patients were interviewed on three occasions over one year, it allowed the opportunity to discuss and clarify evolving themes with patients. Finally, a reflexive approach that considers the impact of the researcher's perspective on the interpretation is recognised as a facet of quality in qualitative research (Seale, Reference Seale1999; Centre-for-Reviews-and-Dissemination, 2009). FT has a master's degree in Anthropology and has a particular interest in explanatory models, which may have influenced her conceptual interpretation. In addition, FT and KB are both physiotherapists with experience in treating patients with PLBP. Although neither was involved in delivering the treatment programme, this may have had an impact on their interpretation. However, we did not intend at the outset to explore patients’ experience of general practice and argue that the themes presented in this paper emerged inductively from the data. Several themes emerged that led to a deeper understanding of the cultural process in which the patient and the GP negotiate their relationship. These themes are transferable to other chronic health conditions.

Findings

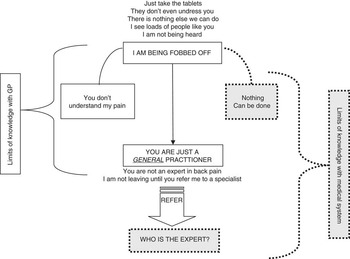

Twenty people agreed to take part in the study (13 women and 7 men) and contacted us to arrange a suitable time and place to meet. Of the nine patients whom we did not interview, three did not want to be interviewed, two did not respond and four were unable to attend the pain management programme at that time. Our sample included patients from a wide range of occupations such as office administration, farming, cleaning, manual work, professional and health care; however, to ensure anonymity, these occupations are not presented in the findings. This paper reports themes that relate to patients’ experience of general practice. Other findings are published elsewhere (Toye and Barker, 2010). We propose three conceptual categories that influence the relationship with the GP and patient with PLBP (Figure 1). First, being ‘fobbed off’ by the doctor, second, the GP as a general practitioner, and third, who is the back expert? These conceptual categories are described below using examples of initial codes (low-inference indicators), followed by a description of the concept using exemplary verbatim quotes. Figure 1 illustrates the development of the major conceptual categories.

Figure 1 Conceptual categories influencing the relationship with the general practitioner and patient with persistent non-specific back pain

‘Being fobbed off’

This theme incorporated initial codes illustrated by low-inference indicators such as: ‘I see buckets of people like you’; ‘the doctor said just take the tablets’; ‘I didn't get a thorough examination’; ‘the doctor said that there is nothing else we can do’; and ‘I just want to be heard’. This conceptual category describes how patients felt that they were not being listened to or understood as a person whose life had been changed by back pain. This made them feel that they were being dismissed by the GP who did not know what to do for back pain and who did not intend to refer them for an expert opinion. Patients felt as if they were on a conveyor belt that was going nowhere. Our interpretation of these initial codes is described below.

‘I see buckets of people with back pain like you’

Patients described their GP as ‘blasé’ towards their back pain and as sometimes trying to make light of a serious situation.

He said it was just wear and tear, and that a man of my age should expect to have that.

I remember going to my GP, he said, ‘well you are a nurse, so, it is not surprising’.

This type of comment often made patients feel guilty about wasting the doctor's time.

The doctor was saying, ‘well there is nothing major wrong with you … there are people walking in and out of here much worse than you, what are you complaining about?’ And that upset me … to me, my pain is my pain … he made me feel a bit guilty.

‘Just take the tablets’

All patients described the GP as ‘keen to dish out drugs’. However, patients saw medication as just treating symptoms rather than ‘dealing with the actual problem’.

From what I remember they just pretty much fob you off … I just think they dish out anti-inflammatories willy-nilly, and pain killers and I think that as long as you are not in their hair, giving them grief, and you are taking your painkillers and it manages it. But it is not actually dealing with it at all.

I though she was very sort of blasé about it, and I resented that because I thought, I have had back pain all this time, and I have managed it myself, and now when I come desperate for help, you give me a packet of painkillers. And you have nothing else to offer me.

Patients were particularly annoyed if the GP put their symptoms down to depression and prescribed medication for this.

And I think the worse time was when he said, ‘so I think we will try you on some Prozac’, cos each time I went to see him I kept getting upset. But I felt that I was being rushed … and I said, ‘but that is an anti-depressant … I am not depressed’ I said ‘I am fed up, I am pissed of, I am suffering. I am not a depressive person at all.

Medication was described as part of the process of being ‘fobbed off’. Just getting rid of symptoms was not seen as curing the problem, thus confirming patients’ allegiance to the biomedical model of pain.

‘I didn't get a thorough examination’

Patients did not accept that a doctor could diagnose a problem without performing a thorough examination, including physical and diagnostic tests such as palpation, X-rays, scans or blood tests. Patients interpreted this as a) not being believed or b) not being taken seriously.

I wasn't terrible impressed … two seconds and he had decided … I probably expected something a bit more thorough. He was very [sigh] … slap dash … I would have expected an X-ray, a blood test, a something … all he had me do was lean forward, and then go sideways down this way, sideways down that way, and that was the full extent of my consultation.

He said, ‘well there is really nothing wrong with you’ … He didn't want to do the proper examination … I think I was in there about five minutes, he just poo-pooed me out of the door. He didn't want to know.

‘There is nothing else we can do’

Patients described how the doctor told them to accept their pain and to get on with life, perhaps even to expect things to become worse. This left them feeling that they had not been heard or taken seriously.

They were very much that, ‘bad backs oh crumbs’, if you have got a bad back then you have just got to learn to live with it … I think every other person you meet in the medical profession gives you a feeling of despondency and negativity about your back.

The expectation with the GP is that this is going to go on for months, so just batten down the hatches, take painkillers and anti-inflammatories … He would just say, ‘well, there is nothing you can do, you can just rest if for a bit, a few days, put heat on it, cos that helps sometimes, try not to sit down, just lay down or stand up. Put a board under the bed’, that sort of thing, blah, blah, blah … and take the pills.

‘I just wanted to be heard’

Patients described how it was important to know that the GP understood them as an individual and the impact the pain was having on their lives.

I didn't feel like I was really being heard … he really hadn't got a clue what it was like to have four children, and a busy house and a busy life and all the rest of it … I just didn't feel he really could grasp my desperation … just two more minutes of probing would make me feel that you cared … you don't expect people to swoon all over you, but just to say, ‘I understand, I think’, and just look as if he is willing to want to help. Rather then, you are a nuisance bothering him for his time, because there are people much worse than you out there.

Dishing out tablets, not conducting a thorough examination and offering no treatment were interpreted as being part of not hearing the person and not understanding the impact of the pain on their lives. An alternative explanation offered (negative case) was that, there actually was nothing that could be done. However, this alternative did not fit with the pervading biomedical model and left the patient with no hope for a cure.

I think the most frustrating thing for anyone with back pain is the fact that you are told there is no treatment … I think that if you don't feel you are being heard and you don't think you are being taken seriously. Or if you feel you are being taken seriously but they really can't do anything, that is the worse thing, you know if you think there is no hope.

These findings present patients’ experience of their GP rather in a negative light. However, it is important to emphasise that these comments only relate to patients’ experience of PLBP and are from a group of patients attending chronic pain management who have been referred on by their GP. We went back to the narratives to seek out more positive comments from patients about the relationship with their GP. Although most comments supported the concepts defined above, the positive comments related to listening, believing and sticking with the patient through their journey.

He is a good listener, and takes in what you say…He actually listens and tries to help and advise you.

My doctor is brilliant … I am very lucky … cos I think I might have lost my temper if someone had said I was faking it.

The doctor that I had before was fantastic. He done everything that he could do and he wouldn't sort of push me out of the way like I felt I had done before.

‘You are just a general practitioner’

In order to explain why they were being ‘fobbed off’ patients constructed the second conceptual category – the GP as ‘just a general practitioner’ who was ignorant about back pain. This explanation was preferable to thinking that there was nothing that could be done. Ignorance about back pain was therefore shifted from the medical system to the individual GP, thus leaving hope for a diagnosis and cure. The GP was not regarded as an expert in back pain and patients were prepared to fight to get a referral to see a specialist.

‘You are not the expert in back pain’

Patients described how GPs lacked specialist knowledge that would allow them to effectively treat back pain, and this is why they ‘fobbed you off’. Only the specialist knows about backs. Only when they had seen the specialist could they move forward.

GPs aren't actually people who actually treat back pain … GPs can't look at your back and say, ‘yeah I think you have got that’. They don't know from just looking at you what is wrong. They look down your throat and you have got a red throat, they can tell you ‘yeah, you have got a sore throat this is what you need to do’. But when you go to the GP and say, I have got back pain, really all they can do is send you off and refer you.

A GP is exactly what it is, a general practitioner, he is not a specialist in bones or whatever, but you really do need an ‘expert’, in inverted commas. I wanted them to refer me so that I could talk to an expert … and even if he [the expert] said there was nothing they could put their finger on, that it was unexplained pain, at least you have talked to the expert so you can carry on.

‘I am not leaving until you refer me to a back specialist’

Patients described the GP's reluctance to refer to the specialist. They felt they had to make a strong case for their referral or the GP would not ‘sign that piece of paper’. This was described as a battle and some described feeling guilty for putting pressure on the doctor.

You have no idea [laugh] how not easy this has been. You are joking. I have not had an easy time getting referred … she said, ‘explain to me again why it is you think you need to be referred’. And it is incredibly emotional this whole thing, when you are in pain, when you are living a stressed out existence with this pain. And I virtually had to justify why and really plead my case again, and felt that, I didn't exaggerate the case, but you know, almost you want to actually say, you know, ‘I am actually bed ridden now’. Because, you just want them to take you seriously … so I forced them to refer me really, feeling terrible guilty because I just thought, you know, if the GP doesn't really think it is necessary, and I am forcing this situation, is this right?

The process of referral was described as having a set trajectory, where certain things had to be endured in order to gain access to the specialist and find a cure.

I went to her thinking, I suppose I am just gonna have to endure this [physiotherapy treatment] to get to the consultant. Because in my mind only a consultant will do.

I have been going back to physiotherapy because I want to keep one foot in the door. The way I look at it is, if you haven't gone through it, you go back to the doctor … he is gonna say, ‘well you didn't do the course that was offered, there is no more I can do for you’. So you have got to try everything.

Who is the back expert?

Our final conceptual category describes how over time patients began to doubt the existence of a ‘back expert’. Having accessed the specialist, patients had expected a definitive diagnosis on the basis of thorough examination and expert opinion. However, they often described conflicting advice from health professionals. These conflicts left them confused about a diagnosis and worried for the future; how could they access the correct treatment if the diagnosis fluctuated? For example:

I had received this letter to say, ‘we believe you have a trace of spondylolisthesis’. And then when I went to see the consultant, he said ‘no, you know your spine is fine. We just think it must be muscular’ … I was very upset … Well who you believe? Do you believe an orthopaedic surgeon, or do you believe a radiologist who is looking at X-rays everyday. I was very confused … it would almost be like somebody saying you have got some terminal illness, and then when they go and see the doctor again they say, ‘Oh no, no that was a mistake don't worry about it, you are fine’.

It is very disconcerting when someone can look at the same pictures and tell you something different … to change the diagnosis … you start to lose a bit of faith in what they are telling you. Cos then you think well is it going to change again. Is somebody else going to say that it is something else entirely different later on?

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual categories and the related tensions in our proposed model. First, they describe how they have been fobbed off by a GP who is just a general practitioner and does not understand them. This narrative allows the patient to continue to use the biomedical model to explain their PLBP; I have something real but the GP is not the expert. In this narrative, limits of knowledge are with the GP. The alternative narrative, ‘nothing can be done’, would involve accepting the limits of medical knowledge. At first, this is rejected as it does not fit the biomedical model, which is integral to legitimacy. However, as patients move through the system and a diagnosis and cure is not provided, some begin to question the concept of the medical expert. Our interpretation helps to understand the context in which the GP and patient must negotiate a therapeutic relationship in the face of diagnostic uncertainty.

Discussion

We support the suggestion that a change in the pervading explanatory model towards a biopsychosocial model is timely (Croft et al., Reference Croft, Peat and Van-der-Windt2010). Fundamentally, PLBP does not fit the biomedical model and thus patients continue to fear that people do not believe them (Jackson, Reference Jackson1992; Kugelman, Reference Kugelman1999; Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Danielson and Norberg1999; Honkasalo, Reference Honkasalo2001; Glenton, Reference Glenton2003; Lillrank, Reference Lillrank2003; Werner and Malterud, Reference Werner and Malterud2003; Werner et al., Reference Werner, Isaksen and Materud2004; Holloway et al., Reference Holloway, Sofaer-Bennett and Walker2007). Attempts to legitimise pain with diagnostic testing are not rewarded nor recommended by best practice guidelines (NICE, 2009). Within this context, the GP has to maintain an ongoing relationship with their patient. A successful resolution of tension is likely to have a direct impact on the patterns of referral to secondary care, patient outcomes and job satisfaction for the GP. Our interpretation supports the discordance between the conceptual models of a patient and a GP. The patient is seeking a diagnosis and cure, whereas the GP is focusing on symptom management, in particular by prescribing pain medication. We have proposed three related conceptual categories (Figure 1). First, patients’ experienced being ‘fobbed off’. Second, rather than accepting that the medicine had nothing to offer, patients shift the lack of knowledge towards the individual GP, who is constructed as ‘just a general practitioner’. This finding is not surprising considering the importance of medical diagnosis to the legitimacy of illness. However, our final category showed that patients began to question the concept of the expert and shift the limits of knowledge to the medical system. Baszanger (Reference Baszanger1992) highlights the discordance in expert opinion by exploring the differing explanatory models related to persistent pain found in two hospital centres specialising in pain management. She distinguishes between two explanatory poles: experts ‘curing through techniques’ (medical model) and those ‘healing through adaptation’ (biopsychosocial model). Discordance in expert opinion can have an impact on the GP's relationship with a patient, who will often come back to the GP confused by what they have been told. In addition to this, discordance in expert opinion shakes the foundations of the biomedical model.

Uncertainty is a prevailing factor of post-modern society where experts are questioned and there is no overarching cultural narrative (Busby et al., Reference Busby, Williams and Rogers1997; Scrambler and Higgs, Reference Scrambler and Higgs1998). This uncertainty is a threat to the biomedical model, which requires certitude. However, the dubiety of the biopsychosocial model can threaten the legitimacy of the person with PLBP. Within this context, the GP must find a satisfactory means of dealing with the diagnostic uncertainty of chronic conditions. Lingard et al. (Reference Lingard, Garwood, Schryer and Spafford2003) suggest that a clinician's ability to manage uncertainty in a clinical encounter is an important transition from student to qualified doctor. This is of particular relevance under conditions where the medical model does not fit a person's illness experience. Lingard et al. (Reference Lingard, Garwood, Schryer and Spafford2003) makes a useful distinction between acceptable and non-acceptable uncertainty in medical practice. Does the patient perceive that the limits of knowledge are with the individual GP (unacceptable) or with the medical system (acceptable)? Our findings suggest that patients with PLBP see the limits of knowledge as with the individual GP and continue to fight for a referral to someone with certain knowledge. Efforts to shift medical uncertainty away from the individual GP might help to increase trust and concordance between a GP and a patient for example, by discussing the limits of diagnostic testing and surgery for PLBP, and focusing on the successes of other approaches adopting a biopsychosocial model (Morley et al., Reference Morley, Eccleston and Williams1999; Guzmán et al., Reference Guzmán, Esmail, Karjalainen, Malmivaara, Irvin and Bombardier2001).

A fundamental paradox for patients with PLBP is that they do not achieve a diagnosis and cure. Patients thus begin to question the limits of knowledge. This paradox illustrates that although cultural models are inherently difficult to challenge, they are not necessarily static (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1978; Pescosolido, Reference Pescosolido1992), and despite inertia, cultural norms have continued to change throughout history. Static cultural systems can hide underlying tension (Turner, Reference Turner1967). For example, patients with PLBP recognise that the biomedical model does not fit their experience (Toye and Barker, Reference Toye and Barker2010). Our final conceptual category supports the tension in the prevailing biomedical model as patients begin to question the ‘back expert’. Dialectic theory suggests that social life is part of an ongoing process of conflict between opposing forces from which a new way of thinking emerges (Forster, Reference Forster1993). Qualitative research allows us to explore the tension within personal narratives and helps us to understand the process by which contradictions are resolved (Baxter and Erbert, Reference Baxter and Erbert1999). Our model proposes tensions in patients’ narrative that can help us to understand the clinical context in which patients and GPs negotiate their relationship. Contradiction and ensuing struggle need not necessarily be seen as negative, but may allow the opportunity for positive change (Baxter and Erbert, Reference Baxter and Erbert1999; Martin et al., Reference Martin, O'brien, Heyworth and Meyer2008). In this example, tension may help the patient to move towards a biopsychosocial explanatory model (Toye and Barker, Reference Toye and Barker2010). We propose that the tensions presented in this study may show that patients are questioning the biomedical model and are thus open to new possibilities.

Another paradox in patients’ narratives is that although the biomedical model infers an illness that has a bodily cause, which is unrelated to a person's virtue, patients need to present themselves as morally worthy persons who have been heard and understood by their doctor. Paradoxically, these moral narratives seem to be particularly important where medical explanations are absent and diagnosis is uncertain (Good, Reference Good1994; Frank, Reference Frank1995; Bury, Reference Bury2001; Honkasalo, Reference Honkasalo2001). This has been found in several qualitative studies of patients with persistent back pain (Jackson, Reference Jackson1992; Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Danielson and Norberg1999; May et al., Reference May, Rose and Johnstone2000; Werner and Malterud, Reference Werner and Malterud2003; Werner et al., Reference Werner, Isaksen and Materud2004). For example, Werner and Malterud (Reference Werner and Malterud2003) found that women with chronic pain worked hard to behave ‘as a credible patient’ so that they would be believed and understood by their doctor. We support the finding that to understand the personal meanings and the impact of illness on a person's life is a key component of patient-centred care (Mead and Bower, Reference Mead and Bower2000). Specifically, it is important to reinforce the credibility of the patient with non-specific back pain. Qualitative research consistently shows that the patient with non-specific pain feels discreditable, particularly as diagnosis remains fundamentally important for legitimacy. Patients are more likely to pursue a diagnostic test if they feel that they are not believed. Our study also shows that it is important to engage in the patient's experience of back pain and discover the impact of pain on their life. This is supported by qualitative studies in persistent pain (Haugli et al., Reference Haugli, Strand and Finset2004; Campbell and Guy, Reference Campbell and Guy2007; Teh et al., Reference Teh, Karp, Kleinman, Reynolds, Weiner and Cleary2009), as well as models of patient-centred care, which emphasise the patient as a unique human being (Mead and Bower, Reference Mead and Bower2000). Patients who felt they had not been understood felt that they had been ‘fobbed off’, and were more likely to pursue an expert diagnosis. If a person feels heard and understood, they are more likely to be open to alternative management strategies. If not, they will continue to pursue diagnosis and cure. Csordas (Reference Csordas2010) suggests that healing is a cultural process that aims to alter the meaning of illness and generate possibilities for the future. The relationship between a GP and a patient is part of this cultural process.

Although we suggest that a shift away from the biomedical model is likely to improve the management of patients with PLBP (Croft et al., Reference Croft, Peat and Van-der-Windt2010), prevailing models are inherently stable because they have a logic grounded in a person's culture that make any challenge appear illogical (Good, Reference Good1994). Our findings show that patients would rather construct their GP as ignorant of back pain than to reject the prevailing biomedical model and accept the possibility that there is no definitive diagnosis or treatment. As the biomedical model seems to be fundamental to personal legitimacy for patients with non-specific back pain, any challenge to this explanatory models should be handled with sensitivity (Helman, Reference Helman2007). This does not mean that a change in model is not timely, relevant or indeed possible. We support the biopsychosocial model as described by Engel (Reference Engel1977) and its focus on the ‘human experience’ of illness. The tensions in our model suggest that some patients do recognise the uncertainty of diagnosis, and this opens up the possibility of cultural change. PLBP epitomises the lack of cultural fit and ensuing dialectic tension that is played out within the primary care consultation. Our findings may be transferable to other chronic health conditions and more research is needed to improve our understanding of explanatory models.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by a grant from the Oxfordshire Health Services Research Committee.