Introduction

Over 10% of patients in primary care report that psychosocial problems impact on their health (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Mercer, Norbury, Watt, Wyke and Guthrie2012). The commonly available options for people presenting with these problems are medication, psychotherapy [cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)] and counselling. Many GPs prescribe antidepressants due to a lack of other options, despite believing that another treatment might be more appropriate (Mental-Health-Foundation, 2005). Social prescribing services can offer a more relevant response to mental health needs. They also have the potential to improve the sustainability of primary care by offering group-based community interventions that have reduced financial and environmental costs compared with standard treatments. Social prescribing services can also reduce future costs by improving vocational skills, social networks and self-esteem, all of which serve to improve mental health resilience (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Catty, Becker, Drake, Fioritti, Knapp, Lauber, Rossler, Tomov, Busschbach, White and Wiersma2007; White and Salamon, Reference White and Salamon2010; Cruwys et al., Reference Cruwys, Dingle, Haslam, Haslam, Jetten and Morton2013).

Social prescribing services support people with mental health problems to access healthcare resources and psychosocial support. These can include opportunities for arts and creativity, physical activity, learning new skills, volunteering, befriending and self-help, as well as support with employment, benefits, housing, debt, legal advice or parenting problems (Kimberlee, Reference Kimberlee2013). This might, for example, entail a GP ‘prescribing’ a community support group to a patient with mild depression. Locally based third-sector organisations often have no direct links to primary-care services, and doctors and patients often need guidance to access these third-sector healthcare resources (Jarvis, Reference Jarvis1987; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Goodenough, Harvey and Hine2000). Social prescribing can help build these connections. Given the current strain on the healthcare system, it is surprising that more effort is not taken to promote these options, particularly when 70% of National Health Service (NHS) GPs state that they would use social prescribing more frequently if they had the option (Mental Health Foundation, 2005).

Two randomised controlled trials (RCT) have investigated the effects of social prescribing for mental health in primary care and both have found it to be effective for reducing symptoms and improving well-being (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Goodenough, Harvey and Hine2000; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Freemantle, Wilson, Sorohan, England, Griffin and Shankar2007). This finding is supported by other qualitative and quantitative studies (Grayer et al., Reference Grayer, Buszewicz, Orpwood, Cape and Leibowitz2005; White et al., Reference White, Kinsella and South2010; Barley et al., Reference Barley, Robinson and Sikorski2012; Makin and Gask, Reference Makin and Gask2012; Stickley and Hui, Reference Stickley and Hui2012; Stickley and Eades, Reference Stickley and Eades2013; Vogelpoel and Jarrold, Reference Vogelpoel and Jarrold2014). There is mixed evidence about whether social prescribing services reduce the financial costs of healthcare. One RCT found that social prescribing proved significantly more expensive due to an increase in prescribed medications and the cost of the social prescribing service staff (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Goodenough, Harvey and Hine2000). The other RCT found that GP and mental health appointments increased while secondary-care referrals (SCR) decreased, leading to an overall decrease in costs for the social prescribing group (although this finding was not significant) (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Freemantle, Wilson, Sorohan, England, Griffin and Shankar2007). An observational study found a significant reduction in both primary-care contacts and prescriptions of psychotropic medication (Grayer et al., Reference Grayer, Cape, Orpwood, Leibowitz and Buszewicz2008). Qualitative studies found wider mental healthcare benefits including improved confidence and self-esteem (White et al., Reference White, Kinsella and South2010; Stickley and Eades, Reference Stickley and Eades2013). There were also benefits noted with respect to mood alongside improved socialisation and occupational outcomes (Stickley, Reference Stickley2010; White et al., Reference White, Kinsella and South2010; Barley et al., Reference Barley, Robinson and Sikorski2012). Furthermore, social isolation, which increases the risk of both physical and mental health problems (Marmot, Reference Marmot, Allen, Goldblatt, Boyce, McNeish, Grady and Geddes2010), can be potentially reduced through social prescribing services as they usually involve attending activities.

This study provides a novel perspective to the potential benefits of social prescribing by assessing its environmental impact. Applying a sustainability framework to healthcare can broaden cost-effectiveness analysis to include the environmental and social impacts as well. This means that clinically effective interventions not only need to be cost-effective but also need to be carbon efficient and aim to improve social outcomes for that patient. Social prescribing services can potentially act to improve the social outcomes of individuals with mental illness – for example, socialisation or educational and employment opportunities (Kimberlee, Reference Kimberlee2013) – but these outcomes are not studied here.

Social prescribing services have the potential to reduce the carbon footprint of primary care by reducing secondary-care use and medication, which both have significant detrimental environmental impacts, and replace these with less carbon-intensive alternatives such as community support groups. Most of the NHS’ carbon footprint is created by clinical activities: the single largest component of its carbon footprint is medication, which makes up 22% (79% of this is from primary and community services) (SDU, 2013). In comparison, buildings and direct energy use comprise 17%. Reducing the carbon footprint of healthcare is important because the targets of the Climate Change Act (2008) for the NHS are to reduce its carbon footprint by 80% by 2050. Along with this, the Lancet Commission has suggested that climate change may well constitute the largest threat to human health in the 21st century (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Abbas, Allen, Ball, Bell, Bellamy, Friel, Groce, Johnson, Kett, Lee, Levy, Maslin, McCoy, McGuire, Montgomery, Napier, Pagel, Patel, de Oliveira, Redclift, Rees, Rogger, Scott, Stephenson, Twigg, Wolff and Patterson2009), and healthcare organisations have a moral responsibility to reduce their very significant contribution to this health threat.

The aim of this study was to determine how a social prescribing service compares with usual treatment, with regard to subsequent healthcare use and the associated financial and environmental costs.

The Connect project

The Connect project was operated by Carlisle Eden Mind and funded by the Tudor Trust from October 2011 to March 2014. By bridging the gap between primary-care and community resources that contribute to individual well-being, it presents the possibility of improving the sustainability of the healthcare service – that is, by improving health and social outcomes, without having to add more infrastructure or health interventions. The service extended choice for a wide range of patients, represented a viable alternative to CBT and medication and represented a suitable option for those experiencing isolation and frequent attenders. Patients spent different periods of time in the Connect project (between 6 and 18 months). Patients were discharged from the Connect service when they were adequately engaged in the community projects or felt that they had improved sufficiently. Connect staff were not trained healthcare staff, but were provided with brief training about local services, completing questionnaires and managing risk.

Features of the Connect service

An ‘Asset Mapping’ exercise was undertaken to identify available services across third, public and private sectors, self-help, self-management resources, educational, leisure and recreational facilities and fitness-, health- and exercise-related activities. Staff in the Connect project then provided signposting based on personal knowledge and experience gained through developing links with local projects. Mental health awareness raising was included and consisted of exploring the Wellbeing Recovery framework (Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Weleminsky, Onifade and Sugarman2012) and encouraging lifestyle change.

Example of community projects used by the Connect service: The Eden Timebank

A ‘timebank’ is a skills exchange and social network where members earn one credit for every hour they spend helping out another member or the wider community (Timebank, 2012). Everyone becomes both the giver and the receiver and co-produces the timebank together. A timebank involves a paid ‘broker’ who facilitates and records exchanges between individuals, develops the membership of the Timebank and crucially gives initial support to members to become involved in exchanges. Members from the wider community are also promoted to join. The Eden Timebank takes referrals from GPs and other healthcare staff.

Methods

This observational study assessed the financial and environmental impacts of the Connect service. Connect staff met with eligible patients to determine which community service best suited their needs. Patients spent between 6 and 18 months in the Connect project and were seen up to a maximum of 20 times. The following two groups were compared: the Connect group and a control group. All patients using Connect (n=30) during December 2013 were compared with a control group. Eligible patients for the Connect group were adults with a common mental health condition, who were not under the care of mental healthcare services, but had been using Connect for at least six months. The control group (n=29) was comprised of patients from the same primary-care practice who had a common mental health condition such as anxiety or depression but were not under the care of secondary mental healthcare services, did not have a substance misuse disorder and did not attend Connect. Patients in the control group received routine care from their general practitioner. There was limited availability for Connect; therefore, control patients were those who would have been referred had there been the capacity within the Connect service, otherwise there should be no difference between the two groups.

Two patients in the Connect group were excluded from the statistical analysis; one due to undergoing detoxification regimes during the study period, and the other because the patient was being managed by mental healthcare services.

Data were retrospectively collected from primary-care health records for a two-year period. The Connect group was measured from six months before referral to 18 months after entry to the Connect, this spanned a period from June 2011 to January 2014; six-month periods were used in this study to analyse healthcare use before and after referral to the Connect. Corresponding data for the control group were collected for the same two-year period.

Outcome measures included the number of GP appointments, prescriptions of psychotropic medications and the number of SCR. The financial and environmental impacts were calculated for each outcome using national averages or accepted conversion factors (see Table 1). The exception to this was the financial cost of medications, which was obtained from the British National Formulary (www.bnf.org). The cheapest cost for each medication was taken. Data regarding how frequently the patient was reviewed following an SCR were not available; therefore, it was assumed that the patient was seen the minimum number of times per referral – that is, once.

Table 1 National tariff costs and carbon footprint conversion factors used in the analysis

kgCO2e=kilograms carbon dioxide equivalent (a proxy measure used in comparisons of environmental impact).

Statistical methods

Statistical significance was assessed at the two-sided 5% level. Mean costs, both financial and environmental, were compared between groups using a t-test; change scores (post-treatment six-month average minus pre-treatment six-month average) were used for this analysis. Percentile bootstrapped 95% confidence interval and corresponding P-values were presented to account for non-normality of the data. All analyses were carried out in Stata SE 13 (StataCorp, 2013). Missing data were not imputed.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences between the financial and environmental costs of healthcare use between groups (see Table 2). There were larger reductions in healthcare use in the Connect group compared with the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant. The most notable result was the non-significant decrease in SCR over 18 months associated with the Connect group [financial cost, mean difference (MD)=£147, P=0.08; carbon cost, MD=46 kgCO2e, P=0.06]. There was little difference between groups regarding psychotropic medication costs and number of GP appointments.

Table 2 Financial and environmental change in costs and carbon footprint before and after Connect per six-month period

SCR=secondary care referral

a Increased costs compared with the pre-Connect period.

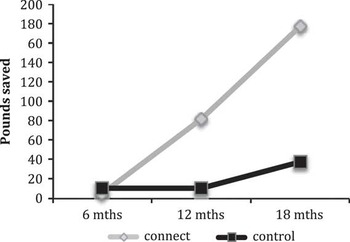

Table 2 displays the financial and environmental costs of healthcare use per six-month period. Cost differences were calculated between the pre-treatment six-month period and the average cost every six months of the treatment period taken at intervals of 6, 12 and 18 months. The Connect project was associated with increased overall financial savings, which was mainly due to a reduction of SCRs: on average a reduction of one SCR per patient over the 18-month study period (see Figure 1). There was less difference between the carbon footprint of the two groups (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 Average financial savings per patient from baseline, following referral to Connect, per six months, averaged over different time periods (£)

Figure 2 Average carbon savings per patient from baseline, following referral to Connect, per six months, averaged over different time periods (kgCO2e)

There were larger reductions in financial cost per patient for SCRs in the Connect group over 18 months (MD=£147). There was little difference between groups regarding costs of medication (MD=£1) and GP appointments (MD=£6) after 18 months. There was little difference between groups in the carbon footprint of psychotropic medications and GP appointments after 18 months. For SCR, reductions in the carbon footprint continued to increase in both groups across the time periods, with the largest, although non-significant, reductions seen in the Connect group at 12 (MD=16 kgCO2e) and 18 months (MD=46 kgCO2e).

The Connect service itself has associated financial and environmental costs. The average number of hours per six-month period for Connect staff seeing patients was 98 h. The staffing cost per hour was £10, and the carbon cost per appointment was 23 kgCO2e (SDU, 2013). Table 3 displays the average costs per patient per six-month period alongside the costs of the Connect service. Although the Connect group was associated with a larger reduction in its carbon footprint compared with the control group, when the carbon footprint of the Connect service itself was included this difference was reversed and the Connect service was associated with an increase in the carbon footprint of 48 kgCO2e per patient (see Table 3). The reductions in financial costs for the Connect group due to reduced healthcare use remained larger than the control group even after the costs of the Connect service were included.

Table 3 The financial and environmental impacts of Connect, per patient, per six months (averaged over 12-month period), alongside costs of the Connect service

a Increased costs compared with the pre-Connect period. The values in bold are cost savings compared with the pre-Connect period

Discussion

Summary

In this study, we found that the Connect social prescribing service was associated with reduced financial costs and an increased carbon footprint per patient (see Table 3). None of the differences between groups reached statistical significance. SCRs were associated with the largest decrease compared with controls. SCRs constitute a major expense for primary care and, in this analysis, are the main reason for the greater reductions in cost for the Connect group, despite the conservative costing used.

The Connect group was associated with a reduction in financial costs but not in environmental costs due to the difference in the financial and environmental impacts associated with GP appointments and SCR. The carbon footprints of a GP appointment and an SCR were similar (59 and 56 kgCO2e, respectively); however, there was a large financial cost difference (£35 and £193, respectively). In the Connect group, there was a larger reduction in SCRs compared with GP appointments, which resulted in a large reduction in financial costs but a smaller reduction in the carbon footprint. In addition, the carbon footprint of Connect appointments (23 kgCO2e/appointment) had a greater effect on the overall carbon footprint than the low financial costs that these appointments had on the overall cost (£10/appointment).

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first of its kind to measure the carbon footprint of a primary-care service alongside its financial cost. The value of this retrospective observational study lies in its novel methodology of analysing the carbon footprint of a service at the primary-care level. However, due to its retrospective nature, the small sample size and lack of randomisation, causation cannot be inferred. Despite noticeable differences between the Connect and control groups, in some areas, statistical significance at a 5% level has not been reached.

This study highlights the inherent difficulty in measuring the financial and environmental impacts of social prescribing services. Problems are encountered when defining boundaries of and attributing costs to clinical services – for example, whether or not patient or staff travel should be included or energy costs for the patient’s home if a telephone appointment is made. As this analysis focussed on impacts associated specifically with NHS care, the environmental and financial costs of running third-sector services that Connect referred to have not been included in this analysis. The environmental and financial costs are likely to be significant, depending on the type of project. A walking group, for instance, might be carbon neutral, but if significant travel is required to get to the walk then this will incur financial and environmental costs. Furthermore, the range of community projects is likely to vary across different regions that will impact on both costs but also patient benefits. Therefore, measuring the carbon footprint and financial cost of the available community projects used in one area is unlikely to be generalisable.

Measuring the carbon footprint of healthcare is problematic (SDU, 2013), and current top-down approaches to obtain the carbon footprint of clinical activities used in this study do not represent the true variation that exists in the carbon footprint of healthcare delivery. Travel has not been included in this analysis and may represent a significant component of the carbon footprint of care, particularly given the rural setting of many primary-care practices. Only running costs of Connect have been included; however, set-up costs can be significant as funding for short-term projects can be significant.

Reference costs have been used to calculate both financial and carbon costs of healthcare service use, which can lead to inaccuracies. The cost for one outpatient assessment was taken as the cost for an SCR (£193 and 56 kgCO2e), the assumption being that the patient was seen by the specialist once and then discharged without follow-up. SCRs often pose a methodological challenge in primary-care studies because they are disproportionally expensive and not frequent. This is the case in this study, where the majority of financial costs are reflected in the costs of SCRs.

Data were available only for 24 patients in the 6- to 12-month period and for 12 patients in the 12- to 18-month period within the Connect group.

Comparison with existing literature

The results from this study of a service development support the current literature about the financial costs of social prescribing, but this is the first attempt at environmental costing. Social prescribing services seem to have the effect of reducing healthcare use to an extent (Grayer et al., Reference Grayer, Cape, Orpwood, Leibowitz and Buszewicz2008), but sometimes the costs of the social prescribing service reduce, negate or outweigh those reductions in healthcare use (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Goodenough, Harvey and Hine2000). Staff with no previous specific training could be sufficient to run the service (Grayer et al., Reference Grayer, Buszewicz, Orpwood, Cape and Leibowitz2005; Reference Grayer, Cape, Orpwood, Leibowitz and Buszewicz2008), which could help keep the financial costs of the service low. Larger reductions in healthcare use, than those seen in this study, are needed before social prescribing services are able to reduce the carbon footprint of healthcare.

Implications for research and practice

Previous evidence suggests that social prescribing services are able to improve well-being scores of individuals with common mental health problems (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Goodenough, Harvey and Hine2000), whereas this study demonstrates that these services are potentially able to pay for themselves through reducing future healthcare costs. At 48 kgCO2e per patient per six months, they are also an effective, low-carbon intervention, compared with CBT or antidepressants, which have a carbon footprint per treatment of around 1000 kgCO2e (NICE, 2010; SDU, 2013). This is an important and novel finding in light of the Government targets for the NHS to reduce its carbon footprint by 80% by 2050.

More research is needed to determine whether the differences noted here are significant when a larger number of patients are studied. A large multi-centre RCT with modelling for future financial and environmental costs alongside patient benefits would provide the evidence required to commission such services and to determine whether they improve the sustainability of primary-care provision.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jennifer Bell, Jennifer Wilson, Kerry Harmer, Rebecca Gibbs, Upper Eden Medical Practice, Kirkby Stephen and Eden Timebank

Financial Support

None.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of relevant national and institutional guidelines and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1974, as revised in 2008.