Background literature

Significant policy initiatives in recent years have created a platform for integrated health, social care and support services in the United Kingdom and internationally. The Health and Social Care Act (HM Government, 2012) called for more integrated working between health and social care organisations in order to improve quality of care and patient outcomes and reduce inequalities. A mandate from the UK Government to the NHS promoted integration for the management of long-term conditions and Integrated Care and Support: Our Shared Commitment (Department of Health, 2013a) identified integrated care as a solution to the major pressures currently facing the health care system with a vision that integrated care will become the norm within the next five years. More recently, the Five Year Forward View (NHS England, 2014) called for greater integration of health and social care in order to deliver better care to patients. This includes hospitals working more closely with primary care, and more multidisciplinary teams operating in the community. The Care Act 2014 (HM Government, 2014) builds on existing government reforms to establish a new approach to adult social care. The Act promotes integration by introducing statutory requirements for local authorities to ensure the integration of social care and support with health provision. Moving forward, Goodwin (Reference Goodwin2017), describes integrated care as a fundamental design feature that will strengthen health care around the world.

Due to the growing interest in the integration of health and social care over the past decade, many different ways have emerged regarding how it operationalised and defined (The Nuffield Trust, 2011; National Voices, 2013). Integration may occur at macro, meso or micro levels. In the United Kingdom and other countries, ‘Accountable Care Organisations’ (ACOs) are formed at a macro level and describe a system of care that creates a single health and social care organisation which is contracted to deliver services to whole populations across large regions. At the meso level, new care models or so-called ‘Vanguard’ sites in the United Kingdom, describe groups of organisations in specific localities that collaborate to provide health and social care services to a defined population (The Kings Fund, 2018). Micro level integration is more about clinical and professional integration to enhance team performance (Billings and de Weger, Reference Billings and de Weger2015). For the purpose of this review, integrated care is considered at the meso level in which providers deliver integrated care for a particular group of people, and at the micro level in which providers deliver care for individual service users and their carers through care co-ordination, care planning and other approaches (Ham and Curry, Reference Ham and Curry2011). The terms horizontal and vertical integration are also used in the literature. Horizontal integration refers to the alignment of health and social across one care setting, for example, primary care, whilst vertical integration occurs across primary, secondary, and community settings (Basi, Reference Basi2014). However, it is acknowledged that these terms may not be used consistently between countries, where horizontal integration may be described as long-term care with the term ‘integrated care’ being reserved for services within health care systems.

Integration is a proposed solution for improving several chronic disease outcomes including those in cardiovascular disease (CVD). The Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes Strategy (Department of Health, 2013b) stresses the importance of integrating health and social care services to address the spectrum of conditions related to CVD. It states that, to achieve this, there must be further integration of care across the CVD pathways, including the development of new service models and a re-alignment of the interactions between hospital, primary and social care services (British Heart Foundation (BHF), 2015).

The term heart failure (HF) is one of a number of diseases that sit within the umbrella term of cardiovascular disease. HF is a common, progressive, life-limiting condition affecting around 550 000 people in the United Kingdom in 2014 (BHF, 2014). It is a disabling and distressing condition which can have a major effect on the quality of life of patients and their families. It is one of the commonest causes of all hospital admissions and the most common cause of admission in those aged over 65 years. The average length of hospital stay for a HF admission is 13 days and one in seven HF patients die in hospital or in the month following discharge. The typical cost per hospital admission episode has been estimated at £3796. HF accounts for 2% of the total NHS budget with 70% of these costs due to hospitalisation. It accounts for 1 million patient bed days per annum and 5% of all emergency admissions (BHF, 2014). In Europe, ~1–2% of the adult population have HF rising to ⩾10% among people >70 years of age. HF, therefore imposes a significant burden on individuals, society and the health and social care economies (ESC, 2016).

The clinical management of heart failure is based on established national and international guidelines (NICE, 2010; ESC, 2016). The BHF (2014) have called for an integrated approach to HF management with robust care pathways to meet patient needs from diagnosis through to end-of-life, including long-term follow-up, social support and palliative care.

Methodology and methods

Design

An integrative review methodology was used according to the approach of Whittemore and Knafl (Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). This consists of four stages: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation and data analysis. This methodology was chosen as it allows for the combination of diverse research designs using both qualitative and quantitative methods, to address a range of outcome measures.

Problem identification

HF is defined as ‘a complex clinical syndrome of symptoms and signs that suggest impairment of the heart as a pump supporting physiological circulation’ (NICE, 2010: 19). The management of HF is a significant challenge for patients and their families and requires substantial financial resource, largely due to high rates of hospital admissions. Integrated care – both horizontal and vertical – has been identified as a model of service delivery with the potential to deliver quality care and improved patient outcomes. To date, there has been no review which considers the evidence on the effectiveness of integrated HF care in terms of outcomes. Given the diversity of integrated HF care models, a further aim is to address the question of what works, for whom and in what context?

Literature search

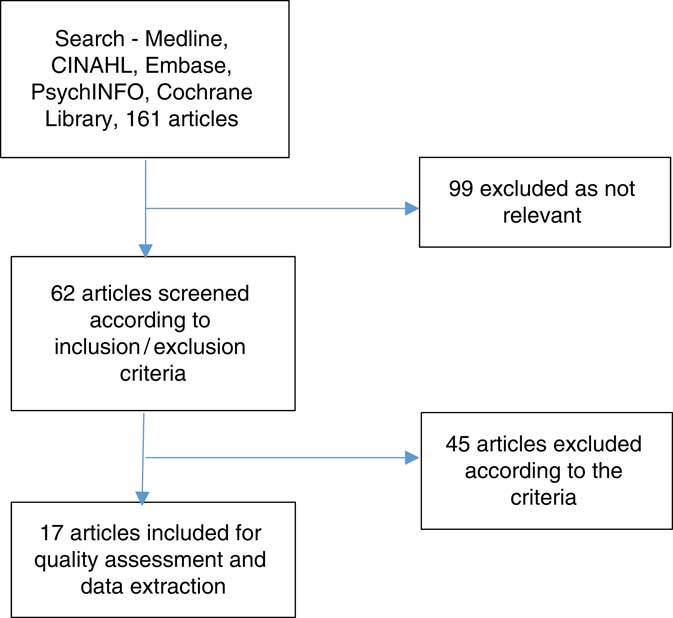

A literature search was undertaken using the databases: Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsychINFO and the Cochrane Library, using key words of ‘heart failure’ OR ‘cardiac failure’ AND ‘integrated’ OR ‘multidisciplinary’ OR ‘interdisciplinary’ OR ‘multiprofessional’ OR ‘interprofessional’ OR ‘collaborative care’. Limitations applied were English Language only and a date restriction of 2000–2017. The reference lists of included articles were hand searched for any further relevant papers. The Journal of Integrated care and the International Journal of Integrated Care were searched individually. A total of 161 articles were sourced which was reduced to 62 based on relevance to the topic.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included if they related to adults with HF; described integrated or multidisciplinary practice involving a minimum of two organisations or professional groups; described a setting of primary care alone or primary care together with secondary care. Only studies which presented data on outcomes were included. Outcomes could be patient-, service-, or resource-related. All empirical study designs were included, using qualitative, quantitative and mixed methodologies.

Articles were excluded if they described CVD in which data relating to HF could not be isolated; if the practice of a single professional group was described; if the setting was exclusively secondary care or if outcomes were not reported. The two authors independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to reach a final list of included articles.

Application of the criteria resulted in 45 articles being excluded, primarily because they did not describe a model of integrated care or were review or editorial pieces. This resulted in a final list of 17 articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Selection of included articles

Data evaluation

The included articles were screened for methodological quality. Given the diverse nature of primary sources, studies were coded according to a two-point criteria (high or low) relating to methodological rigour and relevance (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). The authors independently carried out data evaluation. No articles were excluded on the basis of quality, rather this rating was used to evaluate the strength of the evidence at the point of data synthesis and discussion of findings.

Data analysis

Data were extracted independently by the authors according to a template. A summary of the results is presented in Table 1. Outcomes were analysed thematically.

Table 1 Data extraction

CCM=chronic care model; HFNS=heart failure nurse specialist; RCT=randomised controlled trial; MDT=multidisciplinary team; QUALY=quality adjusted life years.

Of the included articles, six were conducted in the United States, three in the United Kingdom, two in Sweden, two in Australia, one in New Zealand, one in Spain and one in the Republic of Ireland. One study did not state the country. The types of study were randomised controlled trials (n=8), case studies (n=5) and comparative designs (n=4). Two articles presented analysis from several different case studies (BHF, 2015; NHS Improvement, 2010). Narrative data from these case studies was presented individually and with an overarching evaluation. For the purpose of this review, the combined data were used so that the breadth of outcomes could be included. Most articles were assessed as high in terms of both methodological quality and relevance.

Findings

A number of different types or models of integrated HF services were described, involving a range of professional groups.

Vertical integration models

These included liaison between primary care and hospital staff through ‘out-reach’, for example, a follow-up telephone call by the hospital nurse following discharge (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Ledwidge, Cahill, Quigley, Maurer, Travers, Ryder, Kieran, Timmons and Ryan2002; Del Sindaco et al., Reference Del Sindaco, Pulignanon, Minardi, Apostoli, Guerrieri, Rotoloni, Petri, Fabrizi, Caroselli, Venusti, Chiantera, Giulivi, Giovanni and Leggio2007) or ‘in-reach’ where community nurses visited patients with HF before discharge (BHF, 2015). Vertical integration most commonly involved a limited number of professional groups – nurses and doctors. These were specialist staff such as cardiologists and heart failure nurse specialists or non-specialist staff such as hospital nurses and general practice physicians. Dieticians and pharmacists also contributed, usually by providing in-hospital education (Riegel et al., Reference Riegel, Faan, Carlson, Glaser and Hoagland2000; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Cunningham and DiSalvo2011). A wider multidisciplinary team, involving a ‘whole-systems’ approach to care is described by Cawley and Grantham (Reference Cawley and Grantham2011) and pilot studies within the NHS Improvement evaluation (2011). Here, comprehensive strategies link activities between primary and hospital care and represents the highest and most ambitious level of integration. Specific interventions associated with vertical integration models included pre-discharge education, discharge planning, early (within 14 days) community or clinic follow-up and medication optimisation.

Horizontal integration models

Several studies focused on integrated HF and palliative care services at end-of-life. Integration was between HF and palliative care specialist nurses and physicians across different community settings such as home, hospices, nursing homes and community hospitals (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Paull, Introna, Cockburn, Davis, Rees, Gorman, Magann, Lafferty and Dracup2004; NHS Improvement, 2011; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Nunn, Hawkes and Stockdale2012; Brannstrom and Boman, Reference Brannstrom and Boman2014; Sahlen et al., Reference Sahlan, Boman and Brannstrom2016). Horizontal integration models commonly consisted of multidisciplinary team working between doctors, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social services, bereavement counsellors, pastoral care workers and volunteers. Specific interventions associated with these models included multidisciplinary team meetings, joint professional education, telehealth, complex case management, rapid referral for diagnostic echocardiography, shared pathways of care and, for palliative care, out-of-hours advice and hospice-at-home services.

Outcomes

Patient related

Improved quality of life (QoL) was widely reported (Doughty et al., Reference Doughty, Wright, Pearl, Walsh, Muncaster, Whalley, Gamble and Sharpe2002; Del Sindaco et al., Reference Del Sindaco, Pulignanon, Minardi, Apostoli, Guerrieri, Rotoloni, Petri, Fabrizi, Caroselli, Venusti, Chiantera, Giulivi, Giovanni and Leggio2007; Brannstrom and Boman, Reference Brannstrom and Boman2014; BHF, 2015) with better symptom control and improved functional status (Del Sindaco et al., Reference Del Sindaco, Pulignanon, Minardi, Apostoli, Guerrieri, Rotoloni, Petri, Fabrizi, Caroselli, Venusti, Chiantera, Giulivi, Giovanni and Leggio2007; Brannstrom and Boman, Reference Brannstrom and Boman2014; BHF, 2015). Self-management education resulted in improved patient knowledge and self-management ability (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Ledwidge, Cahill, Quigley, Maurer, Travers, Ryder, Kieran, Timmons and Ryan2002; Asch et al., Reference Asch, Baker, Keesey, Broder, Schonlau, Rosen, Wallace and Keeler2005; Brannstrom and Boman, Reference Brannstrom and Boman2014; BHF, 2015). Studies also reported increased survival rates (Stewart and Horowitz, Reference Stewart, Carrington, Marwick, Davidson, MacDonald, Horowitz, Krum, Newton, Reid, Chan and Scuffham2002; Inglis et al., Reference Inglis, Pearson, Treen, Gallasch, Horowitz and Stewart2006; Del Sindaco et al., Reference Del Sindaco, Pulignanon, Minardi, Apostoli, Guerrieri, Rotoloni, Petri, Fabrizi, Caroselli, Venusti, Chiantera, Giulivi, Giovanni and Leggio2007; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart and Horowitz2012; Comin-Colet et al., Reference Comin-Colet, Verdu-Rotellar, Vela, Cleries, Bustins, Mendoza, Badosa, Cladellas, Ferre and Bruguera2014) which was presented as a 36% reduction in all-cause mortality and median survival twice that of a control group.

Service related

Reduced hospital admissions/readmissions was the most commonly reported outcome (Riegel et al., Reference Riegel, Faan, Carlson, Glaser and Hoagland2000; Doughty et al., Reference Doughty, Wright, Pearl, Walsh, Muncaster, Whalley, Gamble and Sharpe2002; Stewart and Horowitz, Reference Stewart, Carrington, Marwick, Davidson, MacDonald, Horowitz, Krum, Newton, Reid, Chan and Scuffham2002; Del Sindaco et al., Reference Del Sindaco, Pulignanon, Minardi, Apostoli, Guerrieri, Rotoloni, Petri, Fabrizi, Caroselli, Venusti, Chiantera, Giulivi, Giovanni and Leggio2007; Cawley and Grantham, Reference Cawley and Grantham2011; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Cunningham and DiSalvo2011; NHS Improvement, 2011; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart and Horowitz2012; Brannstrom and Boman, Reference Brannstrom and Boman2014; Comin-Colet et al., Reference Comin-Colet, Verdu-Rotellar, Vela, Cleries, Bustins, Mendoza, Badosa, Cladellas, Ferre and Bruguera2014; BHF, 2015) along with a reduction in the length of hospital stay (Riegel et al., Reference Riegel, Faan, Carlson, Glaser and Hoagland2000; Inglis et al., Reference Inglis, Pearson, Treen, Gallasch, Horowitz and Stewart2006; Del Sindaco et al., Reference Del Sindaco, Pulignanon, Minardi, Apostoli, Guerrieri, Rotoloni, Petri, Fabrizi, Caroselli, Venusti, Chiantera, Giulivi, Giovanni and Leggio2007; NHS Improvement, 2011; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart and Horowitz2012; BHF, 2015). Readmission rates fell by between 11 and 57% with the most significant reductions in <30 day readmissions. Length of stay fell by between 8 and 14 days. A reduction in the number of hospital admissions and reduced length of stay was confined to patients with mild/moderate HF (NYHA, Class II) in one study, suggesting those with more severe HF may still require frequent admissions.

Improved prescribing practices were reported with more effective up-titration and prescription of β-blockers and ACE-inhibitors (Asch et al., Reference Asch, Baker, Keesey, Broder, Schonlau, Rosen, Wallace and Keeler2005; Inglis et al. Reference Inglis, Pearson, Treen, Gallasch, Horowitz and Stewart2006; Del Sindaco et al., Reference Del Sindaco, Pulignanon, Minardi, Apostoli, Guerrieri, Rotoloni, Petri, Fabrizi, Caroselli, Venusti, Chiantera, Giulivi, Giovanni and Leggio2007; Cawley and Grantham, Reference Cawley and Grantham2011; BHF, 2015). Better care co-ordination, comprehensive documentation and reduced duplication is cited by the BHF (2015) and Cawley and Grantham (Reference Cawley and Grantham2011). Earlier patient identification and diagnosis through, for example, rapid access to echocardiography was also reported (BHF, 2015). At end-of-life, a greater number of patients died at home or in their preferred place (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Paull, Introna, Cockburn, Davis, Rees, Gorman, Magann, Lafferty and Dracup2004; NHS Improvement, 2011; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Nunn, Hawkes and Stockdale2012). This is an important quality indicator aligned to the End of Life Care Strategy (DH, 2009). Finally, greater satisfaction and up-skilling was reported by staff in one study (BHF, 2015).

Resource related

Studies by Riegel et al. (Reference Riegel, Faan, Carlson, Glaser and Hoagland2000), Stewart and Horowitz (Reference Stewart, Carrington, Marwick, Davidson, MacDonald, Horowitz, Krum, Newton, Reid, Chan and Scuffham2002), Del Sindaco et al. (Reference Del Sindaco, Pulignanon, Minardi, Apostoli, Guerrieri, Rotoloni, Petri, Fabrizi, Caroselli, Venusti, Chiantera, Giulivi, Giovanni and Leggio2007), Stewart et al. (Reference Stewart and Horowitz2012) and Sahlen et al. (Reference Sahlan, Boman and Brannstrom2016) all reported reduced costs associated with integrated HF care, although rarely is an economic analysis presented. Although staff costs may be increased, this is offset by reduced hospital admission rates and length of stay, and reduced indirect costs due to improved patient-related outcomes.

Discussion

Frequently, multiple interventions are described as part of an integrated HF service which means it is difficult to determine which interventions have the greatest impact on what outcomes, in specific contexts. However, there are commonalities between the reviewed models which suggest that integrated HF systems which include some or all of these features may result in improved outcomes. These features are: liaison between primary and secondary care services to facilitate a planned discharge, early (<14 days) and medium term (6 months) follow-up, patient self-management education provided by a multidisciplinary team, medication optimisation, multidisciplinary team working; shared education and the development and implementation of comprehensive patient pathways across settings.

Jaarsma et al. (Reference Jaarsma, Larsen and Stromberg2013) developed a guide for home health in HF patients from a literature review, a survey of HF management programmes and expert opinion. They concluded that care should consist of integrated multidisciplinary working, patient and partner participation, the development of care plans with clear goals, patient education, self-care management, appropriate access to care and optimised treatment. The present literature review is consistent with this guide, although patient and partner participation has not been widely adopted.

Multidisciplinary teams most commonly consisted of doctors and nurses, both specialist and non-specialist. Dietician and pharmacist input is also cited, most specifically in providing patient education in relation to diet and medication management. This is not an unsurprising finding given the importance of a low sodium diet and fluid management and adherence to complex medication regimes (NICE, 2010; ESC, 2016). However, in general, there is an absence of other professional groups, most notably mental health professionals and social care staff. Integrated care in HF as in other services often remains health-dominated (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin2017). This needs to be addressed if the ambition for integrated care is to be realised.

A few studies detailed either the severity or type of HF. Although Riegel et al. (Reference Riegel, Faan, Carlson, Glaser and Hoagland2000) differentiated between New York Heart Association (NYHA) (1994) functional classifications (I-IV), in determining outcomes, the stage of the disease was not discussed in other studies beyond stating that HF was chronic or advanced (terminal). Similarly, the type or aetiology of HF was infrequently stated. Given that the management and prognosis for left ventricular systolic dysfunction and right-sided heart failure, for example, are significantly different (NICE, 2010; ESC, 2016), it seems likely that integrated care models will produce different outcomes in these specific populations. It therefore, remains unclear whether the positive outcomes cited are confined to different levels of severity or types of HF.

The search for effectiveness and clearly defined patient outcomes through integrated care service delivery in general remains elusive, due to patient multi-pathology, multiple integrated care configurations and methodological design challenges (Billings and Leichsenring, Reference Billings and Leichsenring2014). However this review has demonstrated that focusing on a single disease can cast a sharper spotlight on pathway solutions. There are relatively well-developed pathways for palliative and end-of-life care for cancer patients but these are less well developed in other diseases such as HF and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. However, this review has indicated that integrated HF and palliative care at end-of-life can produce significantly improved patient outcomes.

Conclusion

The management of HF presents complex challenges for individuals, their families and caregivers, society and health and social care economies. To address this, a number of countries have implemented integrated HF services either involving multidisciplinary team working in primary and community care, or across primary, community and secondary care settings. Multidisciplinary teams most frequently include specialist nurses and doctors but also pharmacists and dieticians. There is good evidence to suggest integrated HF care produces better outcomes for patients and improved care co-ordination across services and organisations. There may also be a reduction in costs, primarily due to reduced hospital admission rates and length of stay. A number of features of integrated HF care models are identified which are most likely to result in improved outcomes. These include liaison between primary and secondary care to facilitate planned discharge, early and medium term follow-up, multidisciplinary patient education and team working including shared professional education, medication optimisation and the development and implementation of comprehensive care pathways across settings.

Limitations of the review

There is considerable heterogeneity of integration models, methodologies and outcomes so that meta-analysis is not possible. However, an integrative review does allow conclusions to be drawn. Only articles published in English were included which may limit both the scope and the generalisability of findings. Although some authors reported the challenges of implementing integrated HF care, outcomes were exclusively positive which may suggest some publication bias.

Implications for policy and practice

Service commissioners and provider organisations should develop integrated health and social care services for HF, including at end-of-life. This includes the development and implementation of agreed care pathways spanning primary and secondary care with consideration given to a core set of interventions. The effectiveness of these pathways, within specific contexts, should be evaluated. There is not a one-size fits all model; effective integration depends on the availability of resources and the context within which health and social care systems operate. Patients and carers should be involved in the co-design of services.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Professor Jenny Billings, Director, Integrated Care Research Unit, Centre for Health Services Studies, University of Kent, for peer review.

Financial Support

This review received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.