Several studies show consistent and important roles for textile production, trade, and consumption, especially of wool items, in the Bronze Age political economies of the eastern Mediterranean (Barber Reference Barber1991; Burke Reference Burke2010; Nosch Reference Nosch2011; Reference Nosch2015; Wright Reference Wright2013; Breniquet & Michel Reference Breniquet and Michel2014; Harlow et al. Reference Harlow, Michel and Nosch2014; Andersson Strand & Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015a). As analytical techniques have expanded, studies also shed light on textiles and textile production at this time in continental Europe (Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen1992; Gillis & Nosch Reference Gillis and Nosch2007; Gleba Reference Gleba2008; Reference Gleba2012; Gleba & Mannering Reference Gleba and Mannering2012; Grömer et al. Reference Grömer, Kern, Reschreiter and Rösel-Mautendorfer2013; Grömer Reference Grömer2016). Although analyses of textile fragments and tools exist, much remains to be done to grasp the socio-cultural and political significance of textiles and, particularly, the wool textile economy of Bronze Age Europe. We need to study specific and variable contexts of production, trade, and consumption. Because textiles are not normally preserved archaeologically, tools for textile manufacture, especially ceramic or stone spindle whorls, are critical for investigating context and scale of production. In this article we present a study of spindle whorls from the Bronze Age Terramare settlement of Montale in the Po Valley, Italy, and their role in community-based specialised wool economy. An exceptional number of spindle whorls (over 4000 items) have been found at this settlement. What is the significance of this concentration? Our thesis is that such a high density of whorls suggests intense textile production and that at least one of the outcomes is likely to have been the provision of exports for trade against required goods such as metals. The characteristics of the archaeological record from both Montale and the rest of the Terramare area (eg, Bernabò Brea et al. Reference Bernabò Brea, Cardarelli and Cremaschi1997a; Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2014; Pacciarelli Reference Pacciarelli2016, 168–70) does not provide clear evidence for significant social inequality either in the settlements (with larger or richer households) or in the necropoleis (with distinguished graves). From a socio-political point of view, we therefore suppose that even large-scale craft practices, such as intense textile production, might have been the outcome of community-based engagement that did not result in significant social inequality.

BRONZE AGE TEXTILES AND WOOL IN CONTINENTAL EUROPE

Any attempt to understand Bronze Age textile production beyond the coasts of the Mediterranean is like doing a jigsaw. Although plentiful, the evidence for textile production is solely archaeological, since no written documents exist. Additionally, the archaeological record is not homogeneously spread, either chronologically or geographically. It seems, therefore, profitable to make use of comparative data and information from areas outside continental Europe, such the Aegean and the Near East.

Although admittedly documenting much more complex political economies than those found in continental Europe, Aegean and Near Eastern written sources provide insight for interpreting broader archaeological patterns. Studies, in particular, of Linear B tablets from palace archives in the Aegean (Killen Reference Killen2007; Reference Killen2015, 1–3; Nosch Reference Nosch2011; Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch and Rougemont2010) and of Assyrian letters from the lower town of the Anatolian city of Kaneš/Kültepe (Wisti Lassen Reference Wisti Lassen2010; Michel & Veenhof Reference Michel and Veenhof2010; Michel Reference Michel2014) record resources and labour investment throughout chaîne opératoires of textile production, and also quality and quantities of demand. Because textiles are seldom preserved (Skals et al. Reference Skals, Möller-Wiering and Nosch2015), texts, which are often concerned with wool and woollen products, provide an important, contemporaneous record as to textile manufacture and trade (McCorriston Reference McCorriston1997; Michel & Nosch Reference Michel and Nosch2010; Wright Reference Wright2013, 397–8; Breniquet & Michel Reference Breniquet and Michel2014; Harlow et al. Reference Harlow, Michel and Nosch2014; Nosch Reference Nosch2015). All in all, Bronze Age wool production in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean was a complicated and dynamic enterprise. A growing demand for clothing of different quality fuelled production activities in specific centres that managed collection and redistribution of raw materials and textile making. It was a year-around activity that relied on access to vast numbers of sheep/goats, paid and/or unfree specialised craft-labour, and conspicuous elite consumption (eg, Burke Reference Burke2010; Breniquet & Michel Reference Breniquet and Michel2014). But can this model be applied to Europe more generally?

Archaeological examples of wool fragments from across Europe (Broholm & Hald Reference Broholm and Hald1940; Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen1992; Bender Jørgensen & Rast-Eicher Reference Bender Jørgensen and Rast-Eicher2016; CinBa database; Gleba & Mannering Reference Gleba and Mannering2012; Grömer et al. Reference Grömer, Kern, Reschreiter and Rösel-Mautendorfer2013; Rast-Eicher & Bender Jørgensen Reference Rast-Eicher and Bender Jørgensen2013) suggest that, early in the 2nd millennium bc, wool became a sought-after material beyond the Mediterranean coastal region. At about the same time, changes in sheep culling suggest that, in some continental regions, raising sheep became geared to wool production (eg, Vretemark Reference Vretemark2010). In addition, strontium isotope analyses of woollen clothing from several 14th century bc oak-log coffin graves (Denmark) document that most preserved textiles from these elite contexts were made with non-local wool (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015; Reference Frei, Mannering, Vanden Berghe and Kristiansen2017). Considering that no convincing archaeological evidence exists for textile manufacture in Bronze Age Scandinavia (eg, Bergerbrant Reference Bergerbrant2007, 49; forthcoming; Sofaer et al. Reference Sofaer, Bender Jørgensen and Choyke2013, 480), and in disagreement with earlier proposals suggesting that wool might have been a Nordic export (eg, Randsborg Reference Randsborg2011, 110), those isotopic analyses hint at the existence of a continental Bronze Age trade providing wool to the north. The archaeological evidence from the Bronze Age Po valley in northern Italy, as presented in this paper, represents a convincing case that, during the 2nd millennium bc, wool economies emerged and developed beyond the coastal region of the Mediterranean to supply continental demand.

BRONZE AGE WOOL IN CONTINENTAL ITALY

The earliest spun wool fibres from the Italian peninsula (Bazzanella Reference Bazzanella2012; Bazzanella & Mayr Reference Bazzanella and Mayr2009, 35, 41–6, 79–8) are from the Early Bronze Age Alpine lake dwellings (Polada Culture, c. 2200–1650 bc).Footnote 1 Although scanty, they suggest that both the material and the production process were well-known, at least in the northern part of the peninsula, long before the Middle Bronze Age evidence from Montale. The earliest pure woollen fabric is a fragment of tabby weave from the Terramare settlement of Castione dei Marchesi (Parma province), likely dated to the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1650–1300 bc)Footnote 2 (Bazzanella Reference Bazzanella2012, 209). Microscopic analyses of its fibres suggest that the wool came from sheep resembling today’s Soay breed (Gleba Reference Gleba2012, 328–9), which moult once a year to yield c. 0.3–0.9 kg of wool (Robson & Ekarius Reference Robson and Ekarius2011, 195). This figure corresponds well to the wool unit in Aegean archives, expressed by the sign *145/LANA, which seems to signify a wool sack of c. 3 kg, containing four adult sheep fleeces of c. 750 g or ten fleeces of c. 300 g from mixed flocks (Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch and Rougemont2010, 340–4). It seems, therefore, that local Terramare sheep most likely resembled, at least in terms of yearly wool yield, those of the Aegean; and that archive documents might provide useful reference material.

According to a neo-Sumerian (c. 2050 bc) source, as many as 4 kg of a fourth-class wool (valued on a 1 [royal] to 5 [poorest quality] scale) were necessary just to obtain an average (guz-za) fabric of c. 3.5 × 3.5 m (eg, Andersson Strand & Cybulska Reference Andersson Strand and Cybulska2013, 113–8). Considering the probable low productivity, in terms of yearly wool yield, of the Terramare sheep, as in the Aegean and the near East (Halstead Reference Halstead1999; Biga Reference Biga2011; Firth Reference Firth2014), any Middle Bronze Age specialised wool production in the Po plain would have required management of large herds. As discussed below, a good number of Terramare sites, including Montale, show evidence of intense sheep husbandry. Although sheep provide a range of other products as well, it is evident that wool was, at least potentially, a widely available raw material.

TERRAMARE AND BRONZE AGE TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN THE PO VALLEY

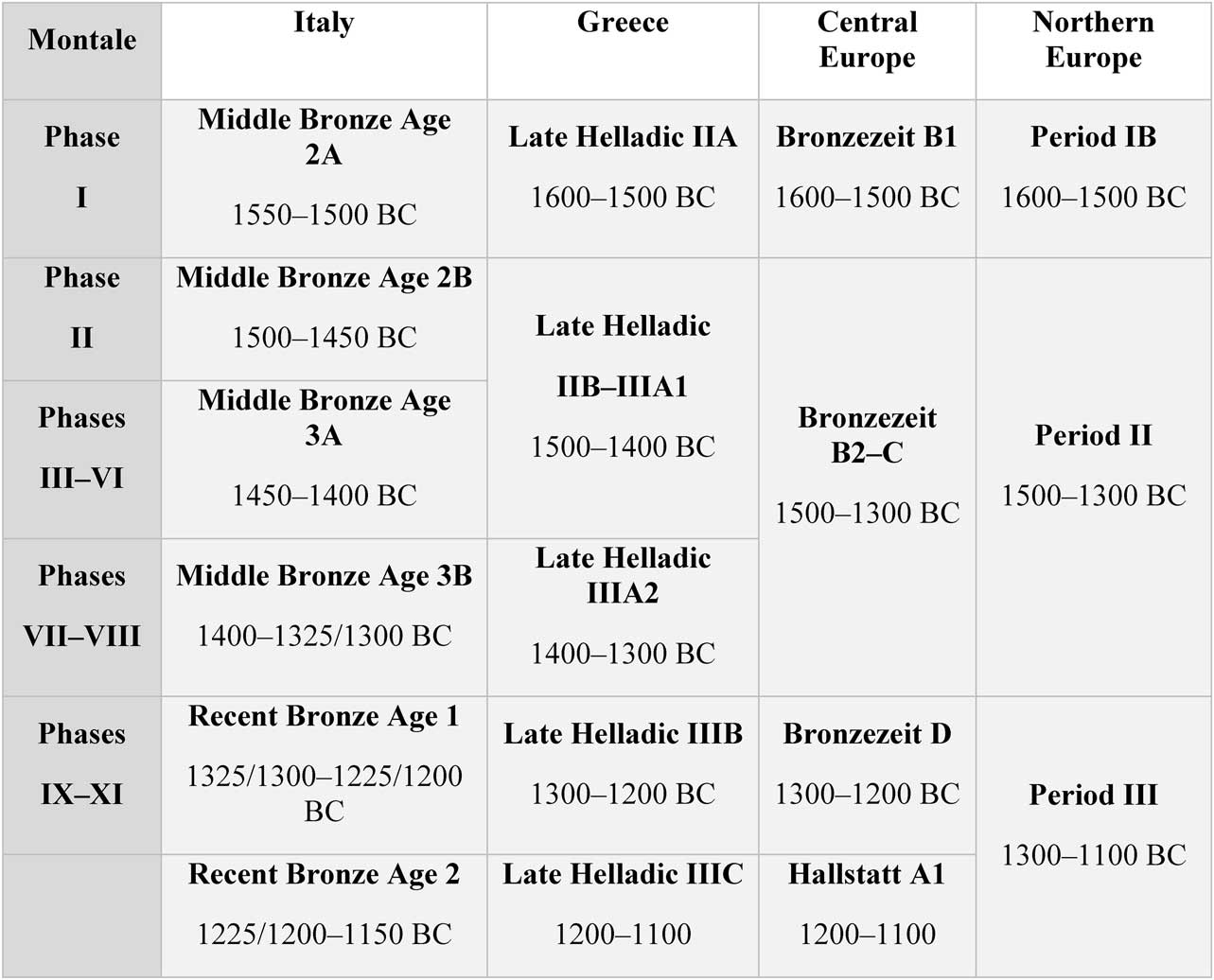

To investigate contexts and scale of textile production beyond the coastal zone of the Mediterranean, we consider the Terramare culture and its settlement of Montale (Modena province). Terramare defines Middle/Recent Bronze Age (Fig. 1) populations of the central part of the Po plain in northern Italy (Bernabò Brea et al. Reference Bernabò Brea, Cardarelli and Cremaschi1997a; Blake Reference Blake2014, 113-49; Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009a; Reference Cardarelli2014; Reference Cardarelli2015; Vanzetti Reference Vanzetti2013).Footnote 3 As an archaeological complex, Terramare displays distinctive settlement organisation and land-use. Initially in the Middle Bronze Age, settlements were primarily small (typically 1–2 ha), with estimated populations of 125/130 inhabitants per ha (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015, 167) confined within substantial fortifications. Subsequently, from Middle Bronze Age 3 into the Recent Bronze Age 1 (Fig. 1), a form of site hierarchy emerged with some larger settlements over 10 ha that held populations of perhaps 1000 or more (eg, Pacciarelli Reference Pacciarelli2016, 168–71). At the same time, extensive irrigation systems have also been documented (eg, Cremaschi et al. Reference Cremaschi, Pizzi and Valsecchi2006, 89; Vanzetti Reference Vanzetti2013, 271–2). For European prehistory, the Terramare irrigation complexes represent an unusually high investment in engineered landscapes, and have been interpreted as probably being associated with community (corporate) ownership (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015, 168). Terramare fortified settlements probably asserted a willingness of the community to ‘stand its ground’ in defence of landscape capital (see Earle Reference Earle2017) and mobile wealth such as crops, raw materials, textiles, and, to a certain extent, animals (see Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009b). Existence for war-like violence is seen in the necropolis of Olmo di Nogara from the neighbouring Verona Province, north of the Po River, where several skeletons had received dramatic wounds (Canci et al. Reference Canci, Cupitò, Pulcini, Salzani, Fornaciari, Tafuri and Dalla Zuanna2015; Pulcini Reference Pulcini2014, 130–43).

Fig. 1 Montale’s archaeological phases and contemporary main Bronze Age chronologies

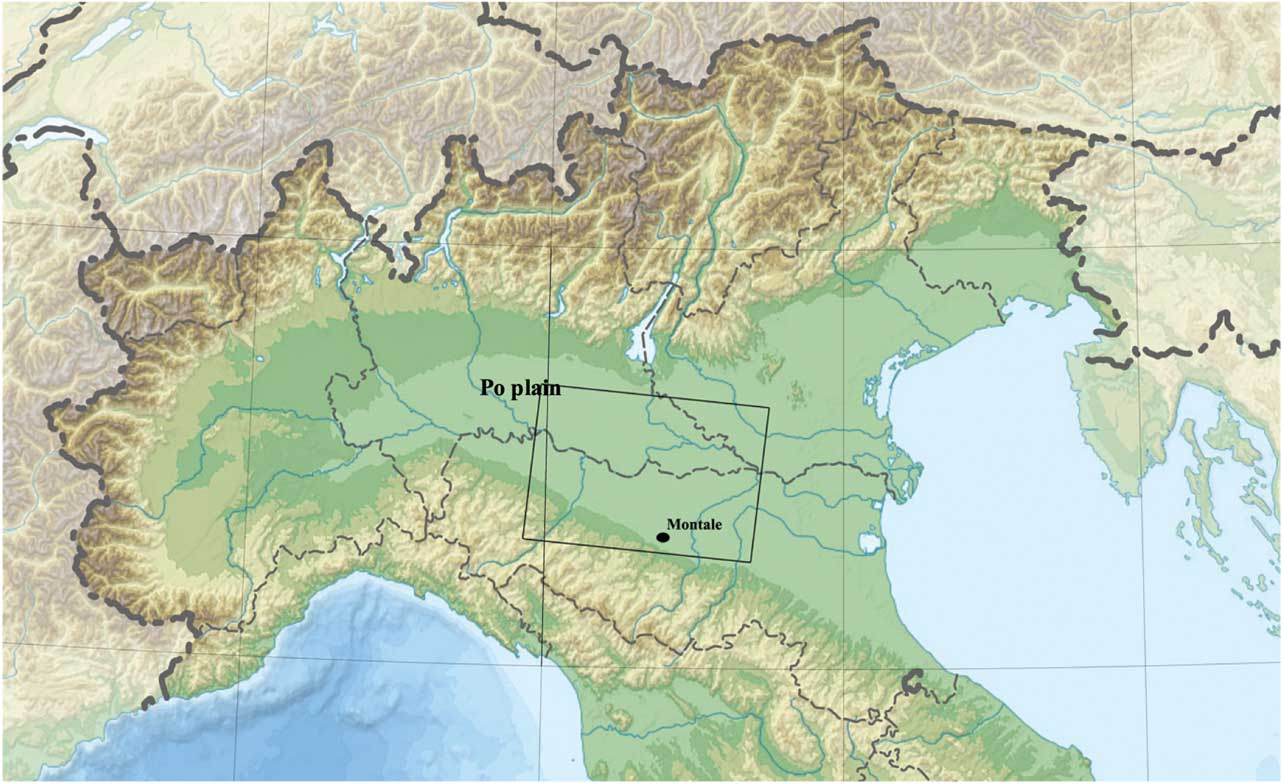

In this study, we concentrate on the Terramare settlement of Montale situated in the landscape of the Po plain in the Modena province, which is open and fertile, and in close vicinity to the mountainous areas of the local Apennines (Fig. 2; Bernabò Brea et al. Reference Bernabò Brea, Cardarelli and Cremaschi1997b; Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2006; Cavazzuti & Putzolo Reference Cavazzuti and Putzolo2015). In Roman times this province had a dense human population, intensive agriculture, substantial animal husbandry, favoured among other things by vicinity to the Appennines summer pastures, and was renowned for its wool production (Corti Reference Corti2012). Archaeozoological evidence suggests that specialised wool production also existed here in the Bronze Age. Compositions of domesticated animals in the Terramare culture broadly (De Grossi Mazzorin Reference De Grossi Mazzorin2013) and at the site of Montale specifically (Table 1), show that sheep/goat herding was significant (De Grossi Mazzorin & Ruggini Reference De Grossi Mazzorin and Ruggini2009). Ovicaprids were consistently present on the plain throughout the Middle and Recent Bronze Age, increasing through time to more than 50% of the animal assemblage at some settlements (De Grossi Mazzorin Reference De Grossi Mazzorin2013, table 1). Although the archaeozoological data from many sites, including Montale, have been only published preliminarily, where information about culling strategies are available, it would seem that a mixed pastoral economy, producing both meat and wool, dominated across the plain, while only minor attention was paid to milk production (De Grossi Mazzorin Reference De Grossi Mazzorin2013; Riedel Reference Riedel1989; Reference Riedel2004). The presence of clay sheep figurines indicates that they had a social and symbolic significance (Desantis Reference Desantis2011, 38; Bianchi & Bernabò Brea Reference Bianchi and Bernabò Brea2012, fig. 1).Footnote 4

Fig. 2 The Po plain in Northern Italy with the site of Montale and the area of the terramare

Table 1 ANIMAL POPULATION AT MONTALE. APPROXIMATE PERCENTAGE VALUES (STRATIGRAPHIC EXCAVATIONS) (COURTESY OF JACOPO DE GROSSI MAZZORIN)

Terramare communities in general appear to have exploited local environmental, technological, and organisational advantages to meet subsistence needs and to produce exports to exchange for needed non-local commodities. Metal tools, for example, were widely produced and used, but no local sources of metal were available in the plain. For some Terramare communities, a likely export in exchange for the metal might have been textile products. In this respect, the case of Montale, analysed here, might not have been an isolated one. It is, for instance, possible that specialised weaving activity existed at Beneceto (Parma province), where hundreds of fragmentary loom weights have been recovered (Lincetto Reference Lincetto2006, 138–56). Also, at Poviglio (Reggio Emilia province), weaving might have been specialised; a conspicuous number of loom weights and probable evidence of standing warp-weighted looms have been recovered in various structures from different parts of that settlement dated to different Bronze Age phases (Bernabò Brea et al. Reference Bernabò Brea, Bianchi and Lincetto2003; Bianchi Reference Bianchi2004).Footnote 5

Material from 19th century collections, as recorded in Modena Civic Museum registers, provides a striking picture of different frequencies of textile tools from various provincial sites (Table 2). Although these partly unsystematic collections do not offer a safe base for further analyses and comparisons, they provide a good indication of the likely different politico-economic choices of the various settlements as to the intensity of textile manufacture. On the basis of the remarkable quantity of recovered textile tools, Montale provides good evidence for understanding one context of Bronze Age textile production. It suggests, we argue, that it was a community-based specialist production, as defined by Cathy Costin, characterised by ‘autonomous individuals or household-based production units, aggregated within a single community, producing for unrestricted regional consumption’ (Costin Reference Costin1991, 8).

Table 2 FINDS COLLECTED DURING THE 19TH CENTURY FROM TERRAMARE SETTLEMENTS OF THE MODENA PROVINCE, AS RECORDED IN MODENA CIVIC MUSEUM REGISTERS (COURTESY OF GIANLUCA PELLACANI)

THE TERRAMARE SETTLEMENT OF MONTALE

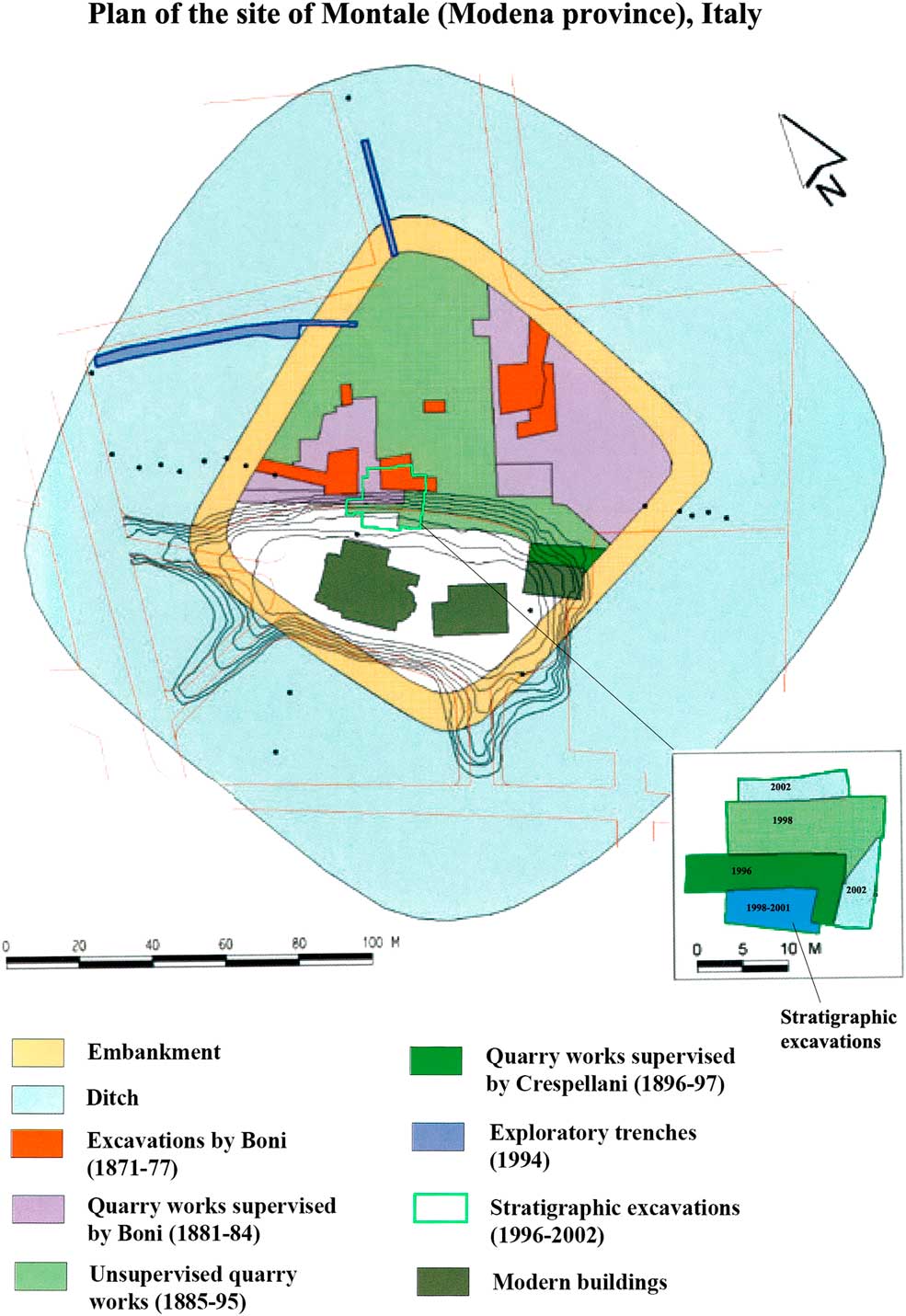

Montale was a typical 1 ha fortified Terramare settlement, which was probably home to a local group of perhaps 130 people. It was surrounded by a massive ditch c. 40 m wide and 3 m deep, which would have been filled with water (Fig. 3) to serve several functions including defence (Cardarelli & Labate Reference Cardarelli and Labate2009a, 28–30). There is no evidence to suggest a social hierarchy at Montale, although some form of local leadership was most probably involved in the construction of both the ditch and the imposing defensive embankment that lay between the ditch and the settlement. The embankment was still preserved for a width of 10 m and an height of 2 m at the end of the 19th century (Cardarelli & Labate Reference Cardarelli and Labate2009a). The site was partly investigated during the 19th century (cf. Fig. 3), but it is only thanks to recent stratigraphic excavations of a c. 45 m2 portion of the settlement (luckily spared by the local manure quarry works, see Fig. 3) that a densely settled space could be revealed. The material from the excavation also helped establish an 11-phase internal chronology from 1600/1550 to 1250/1200 bc (cf. Fig. 1). The results of the excavation show that houses tended to be built and rebuilt within what look like precisely allocated spaces (Cardarelli & Labate Reference Cardarelli and Labate2009b, fig. 69). They also revealed that the very same space that was occupied by dwellings during Phases I–IV could be used for metallurgical activities during Phase V and return to accommodate housing during the following Phase VI, though in slightly different positions to the earlier structures. In Phase VIII a granary was also present in the excavated area while, during the remaining phases, no structures could be identified (Cardarelli & Labate Reference Cardarelli and Labate2009b). Phase II is best preserved archaeologically and parts of two different buildings and of the space/street between them, dated to this phase, show that the settlement living quarters were organised in an orthogonal layout, in a fashion similar to that investigated at Poviglio, for instance (Bernabò Brea et al. Reference Bernabò Brea, Bianchi and Lincetto2003).

Fig. 3 Plan of the site of Montale with excavation history (elaborated from Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009b, fig. 9)

What makes Montale exceptional among Bronze Age settlements, not only in the Po plain but also on a wider continental scale, is its unusually high density of textile tools, particularly spindle whorls (cf. eg, Table 2). Over 90% of the textile tools from here were collected in the 19th century, when compost for farming was being quarried. At this time, Modena Museum partly supervised the recovery of archaeological material (cf. Fig. 3), comprising thousands of finds, although without contextual information (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009b, 16–18). Additional archaeological material comes from well-documented, modern excavations (eg, Candelato et al. Reference Candelato, Cardarelli, Cattani, Labate and Pellacani2002; Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009b). Finds include items relating to spinning (spindle whorls), weaving (in particular loom weights, possibly also loom combs and at least one loom sword, cf. Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009b, fig. 80.17), and sewing implements (needles).Footnote 6

MONTALE’S SPINDLE WHORLS

According to the Modena Civic Museum register, 4454 spindle whorls were collected during the 19th century (Table 2), of which 4089 nearly complete whorls are still preserved. At the same time, 127 loom weights, of which 78 are today preserved in the collection, were also brought to the Modena Museum (Sabatini in press). During the recent stratigraphic excavations a further 182 whorls (Tables 3 & 4) and 17 loom weights were recovered. Considering that many tools (54% of the spindle whorls (N=98; Table 3) and 52% of the loom weights (N=9, cf. Sabatini in press) from recent excavations are fragmentary, the original number of both spindle whorls and loom weights from the Montale quarry excavations must have been much higher than the recorded total of whole textile tools.Footnote 7

Table 3 WHOLE SPINDLE WHORLS FROM THE STRATIGRAPHIC EXCAVATIONS AT MONTALE PER PHASE (N=84)

Table 4 FRAGMENTARY SPINDLE WHORLS FROM THE STRATIGRAPHIC EXCAVATIONS AT MONTALE PER PHASE

This paper focuses on the clay spindle whorls, which are the principal textile tools recovered from Montale. Spindle whorls are flywheels that, fixed on a spindle shaft, help maintain rotation for spinning (Barber Reference Barber1991, 51–4; Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, 77–8). Spinning is the act of ‘twisting and drawing out (or drafting) the fibres of the raw material into a thread’ (Barber Reference Barber1991, 41). Although spinning can be done in many ways (eg, Barber Reference Barber1991, 39–51; Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen2012, 129), the 4000 + whorls recovered at Montale and their routine presence in other Terramare sites and throughout Italy from the Neolithic (eg, Gleba Reference Gleba2008, 104), suggests that using clay whorls was the locally preferred technique for spinning thread. Spinning is a time-consuming task (Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen2012; Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, 84) and, indeed, it dominates labour time in the textile chaine opératoire. Recent tests (Andersson Strand & Cybulska Reference Andersson Strand and Cybulska2013) confirmed that, of c. 124 working days needed to produce a 3.5 × 3.5 m fabric of average quality from raw wool, as recorded in the neo-Sumerian text mentioned above (Waetzold Reference Waetzoldt1972, T32), one worker would have had to be occupied for over half the time (c. 67 days) just spinning the necessary warp and weft thread. In addition, experiments demonstrate that the level of required skills and time increase consistently when spinning thin, high quality threads (Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen2012, 129; Andersson Strand & Cybulska Reference Andersson Strand and Cybulska2013, 116–8). Although ancient written sources do not seem to document trade in yarn, the production of thread, carried out by carefully recorded specialised labour, must have had a crucial role in both Near Eastern and Aegean economies (see, for instance, Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch and Rougemont2010, 354–6; Firth & Nosch Reference Firth and Nosch2012; Siennika Reference Siennika2014), and we can assume that it was important in contemporary European economies as well.

Montale’s whorls are of various types that are typical of the region with some types showing considerable standardisation as to shape and decoration (Fig. 4; Bianchi Reference Bianchi2004, fig. 280–1; Leonardi Reference Leonardi2012). Only the items from the modern excavations underwent a typological analysis. They have been divided in nine main types: truncated conical (eg, Fig. 4E), biconical asymmetric (eg, Fig. 4C–D), biconical asymmetric with protuberances (eg, Fig. 4F), biconical (eg, Fig. 4B), biconical with concentric marks (eg, Fig. 4A), convex-cylindrical (eg, Fig. 4H), disc-shaped (eg, Fig. 4I), globular (eg, Fig. 4G), and pin-head like (eg, Fig. 4J). Most of the sub-types within each of the main types recur across the sequence (Table 5). Because the stratigraphic excavation were limited (cf. Fig. 3), these samples may be unrepresentative, and so the following hypotheses should be taken with some caution. The greater and more articulated presence of whorls during Phase II might, for instance, depend on the fact that this phase was not only the best preserved, but also the one with larger portions of dwelling structures than other phases.

Fig. 4 Examples of spindle whorls from Montale (photos: S. Sabatini)

Table 5 TYPES OF SPINDLE WHORLS FROM THE MODERN STRATIGRAPHIC EXCAVATIONS PER PHASE

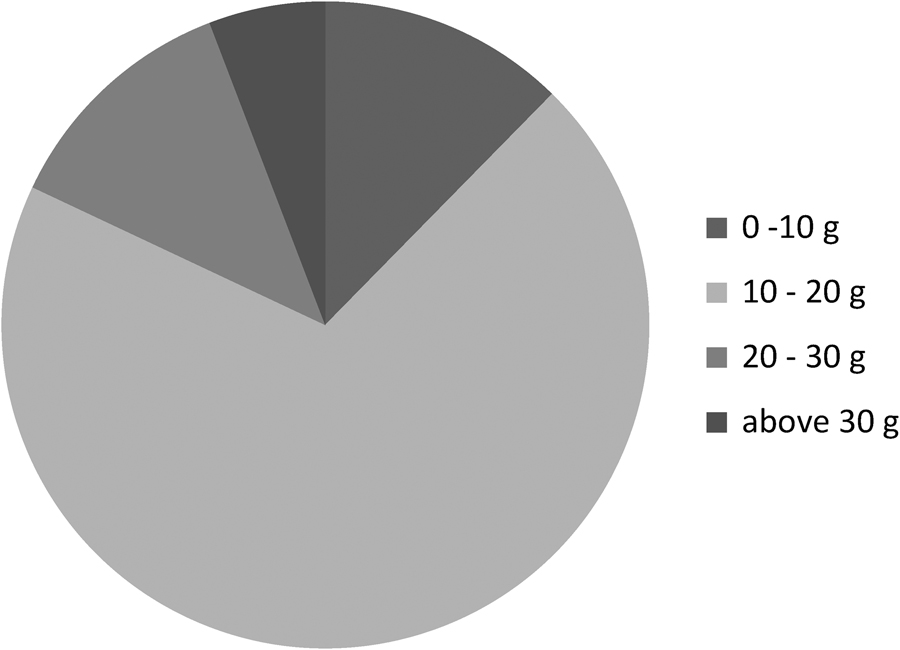

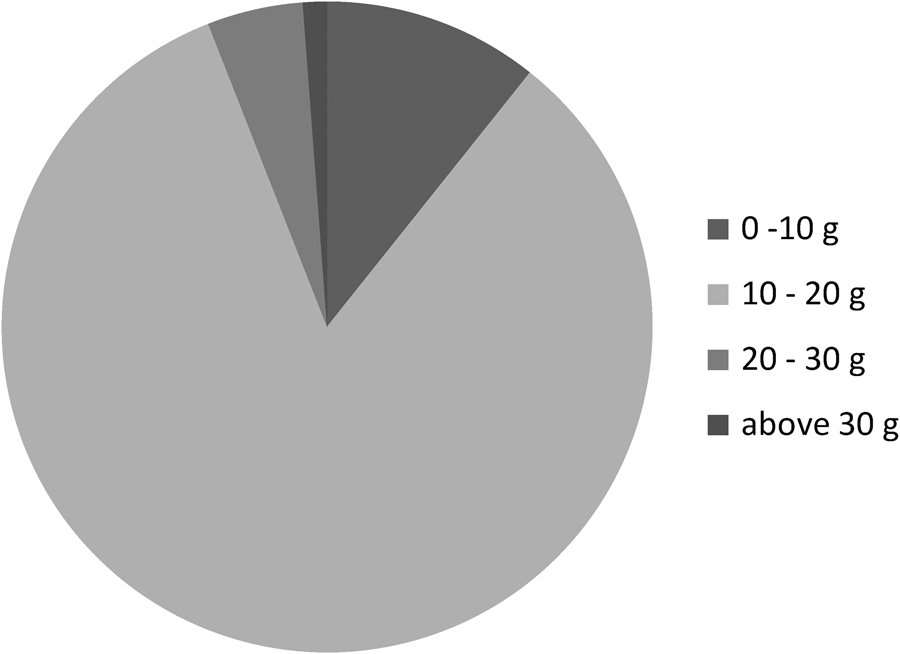

Here we present the analysis of the weight of the whorls, which seem to encompass a wide range of values (see below) with some chronological patterning. Ethnographical and experimental records suggest that weight and, to a certain extent, diameter, rather than shape, are functionally important for spinning. Bearing in mind that the chosen raw material might also influence both spinning techniques and spindle whorl sizes (eg, Barber Reference Barber1991, 42–4; Siennika Reference Siennika2014, 165), light spindle whorls, under 10 g, seem generally best to spin fine/light threads, whilst heavier whorls are more suited to thicker or coarser threads (Liu Reference Liu1978; Barber Reference Barber1991, 51–3; Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand and Nosch2015) or for plying (Gleba Reference Gleba2008, 106). Although recent experiments have questioned these relationships, suggesting that the skills of spinners might be more important (Kania Reference Kania2013), we believe that the analyses of weights can profitably initiate functional discussions. The material has been grouped at 10 g intervals, in accordance with recent experiments (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, 86–7), to provide a framework for further analyses. Among specimens collected during the 19th century, the lightest spindle whorls weight was as little as 1 g, the heaviest, 85.5 g; the majority of whorls (almost 70% of the total, 2848 pieces) weigh 10–20 g (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Spindle whorls from the 19th century collection at Montale according to categories of weight (N=4089)

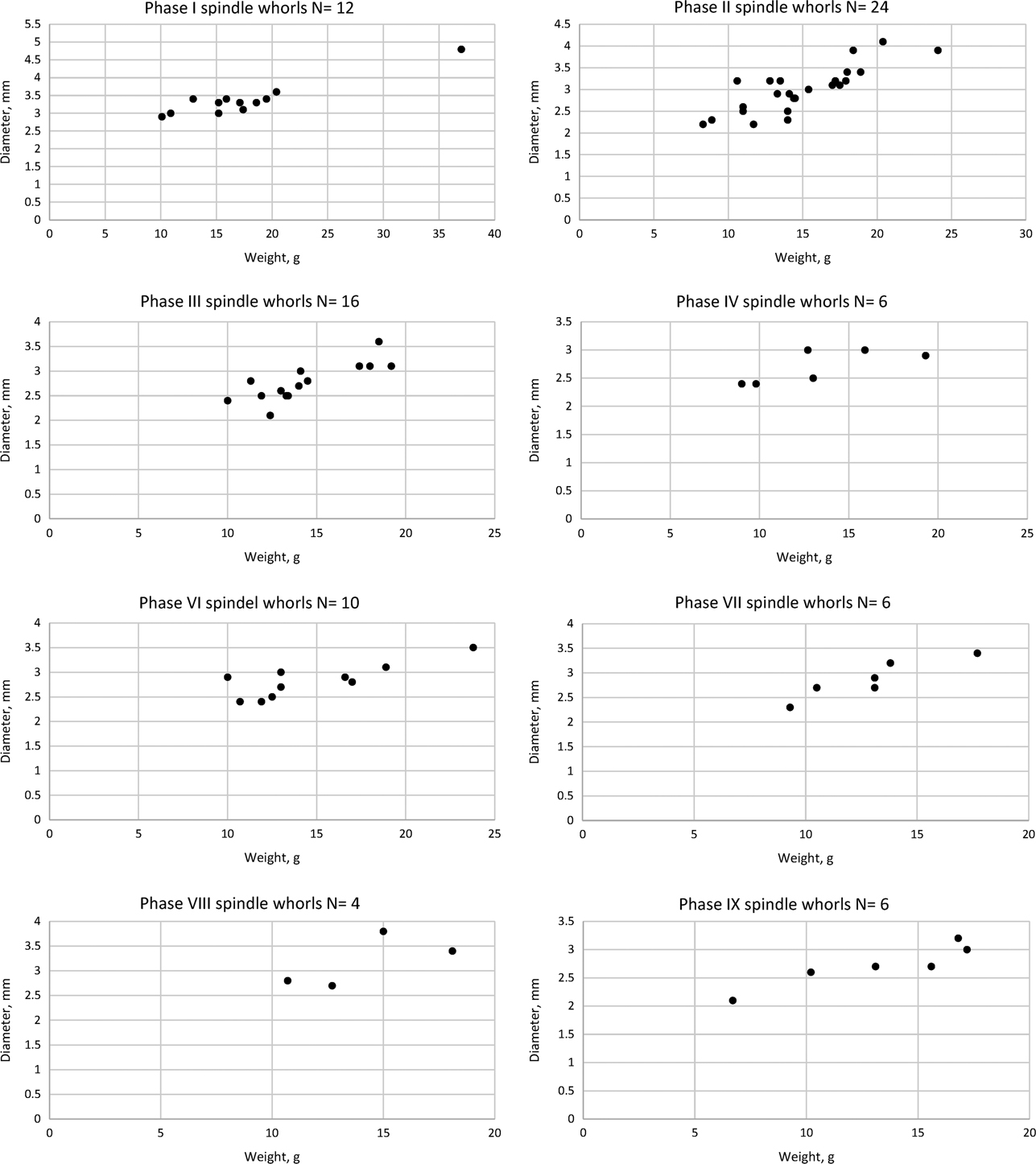

Of the well-dated 84 complete whorls recovered from modern excavations (Table 3), the lightest whorl weighs 6.7 g and the heaviest, 37 g; as in the earlier collections, the majority of whorls were 10–20 g (Fig. 6). We have also attempted to correlate the weights with their diameters among the stratigraphically excavated whorls. The analyses of this sample suggests some diachronic differences, although counts are small. The scatter plot for diameter/weight of the material (Fig. 7) shows that a positive correlation apparently exists and that the larger and heavier whorls characterise the earliest period (Phase I), while (with the exception of Phases II and VI) any other period includes only items below 20 g and the largest number of whorls of 30 mm or less in diameter. Perhaps a craft/tradition prefering large whorls (>30 mm in diameter) occurred mostly in Phases I and II. Finally, the greatest variety of spindle whorls, in terms of both weight and size, appears in Phase II, which might be a sign of more technological experimentation. In general, the great majority of the whorls fall between c. 10 g and 20 g (see also Figs 5–6) suggesting that a rather stable crafting tradition existed at Montale through time, although the frequency of spinning may have changed.

Fig. 6 Spindle whorls from the stratigraphic excavations (1998–2002) at Montale according to categories of weight (N=84)

Fig. 7 Scatter plot of the complete items from the stratigraphic excavations at Montale (N=84) by weight/diameter

Diachronic analysis of spindle whorls from modern excavations, both whole (Table 3) and fragmentary (Table 4), shows that c. 50% (52 whole and 41 fragmentary) belong to Phase I–III and that, with the exception of two fragmentary items, one from Phase V and one from Phase X, practically no whorls exist from Phase V, X, and XI. Small sample sizes, however, make trends unreliable. The lack of spindle whorls from Phase V, for example, clearly reflects that the small area excavated ceased to be a dwelling space during that phase as it was involved primarily in metallurgy. The lack of whorls in Phase X–XI might reflect poor preservation (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009b, 45, 50–1, 63). Although detailed regional studies are needed, which could add important new information, the decrease of clay spindle whorls during the Recent Bronze Age may reflect a transformation in textile production modes or outcomes across the whole Terramare area.Footnote 8

DISCUSSION

On the base of the available data (cf. Bernabò Brea et al. Reference Bernabò Brea, Bianchi and Lincetto2003; Bianchi Reference Bianchi2004; Lincetto Reference Lincetto2006, see also Table 2), the counts of clay spindle whorls from Montale seem to have no equal among Terramare settlements, nor in fact in other Bronze Age European settlements (cf. Gleba & Mannering Reference Gleba and Mannering2012; Grömer Reference Grömer2013; Reference Grömer2016; Kneisel & Schaefer in press). For the Mediterranean, where written sources speak of intense production, the impressive database created by the Centre for Textile Research in Copenhagen, although far from being exhaustive, counts only a total of 3994 entries (Andersson Strand & Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015b, 149), including known evidence from major Bronze Age centres around the Eastern Mediterranean coast. With the exception of Troy (Guzowska et al. Reference Guzowska, Becks, Andersson Strand, Cutler and Nosch2015), spindle whorl counts from all the investigated sites do not exceed a few hundred (Andersson & Nosch Reference Nosch2015). Therefore, the assemblage of thousands of spindle whorls from Montale strongly suggests that the settlement was unusual, specialising in intense yarn production. Although weight distributions (Figs 5 & 6) show wide variation, a significant presence of light whorls (≤10 g) and a clear dominance of medium–light spindle whorls (10–20 g) suggests the production of a variety of threads including thin or fine yarn. That thin yarn was manufactured or used on site has been suggested on the basis of the numerous needles from Montale with small eyes appropriate for thin threads (Pulini & Righi Reference Pulini and Righi2009, 100).

Evidence from Montale suggests that specialised workers were probably active at the site and that production was on a large scale. As discussed earlier, spinning is a sizable task in textile production and so the high quantity of spindle whorls suggests their importance in the settlement’s everyday activities. In this respect, the rather abrupt disappearence of whorls in Phases X–XI (Fig. 1) is difficult to explain, in particular when considering that, during these phases, the number of sheep/goats in the bone assemblage increased (Table 1). Although the representativeness of the excavated collection for the whole site is unknown, one can propose that more intense yarn production occurred during the Middle Bronze Age followed by increasing diversification of productive activities in later phases. One reasonable suggestion is that, at the onset of Montale Phase X, emphasis on raw wool as an export became more profitable than yarn production, perhaps indicating some transformations of regional management practices or an emerging trade in other products. Archaeobotanical samples from modern excavations suggest that, at Montale, another economic transformation occurred at the end of Phase VIII and more evidently in Phase IX. With the introduction of grape there (Accorsi et al. Reference Accorsi, Bandini Mazzanti, Bosi, Marchesini, Mercuri and Trevisan2009, 67; Cardarelli et al. forthcoming), perhaps new products, such as wine, might have replaced spinning as Montale’s primary export. Of course, spinning techniques could also have changed or clay spindle whorls might have been substituted by whorls made in other materials.Footnote 9 Although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn, the consistent economic transformations that seem to have occurred at Montale at the beginning of the Recent Bronze Age are in chronological correspondence with the establishment of settlement hierarchies throughout the Terramare area (eg, Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015; Pacciarelli Reference Pacciarelli2016, 168–72). Montale does not change its size with time, as other prominent Terramare settlements do, but interregional political dynamics probably played a major role in its particular economy.

To understand the social context of any specialised production, it is important to assess its possible link to the political economy that supported the emergence of social hierarchies (Earle & Spriggs Reference Earle and Spriggs2015). The role of specialisation in the formations of social hierarchies has been discussed archaeologically since at least Childe (Reference Childe1942). Brumfiel and Earle (Reference Brumfiel and Earle1987b) have drawn attention to the ability to control some prestige goods, like cloth, by what they call attached specialisation, meaning simply that elites sponsored production and thus effectively controlled distribution of socially meaningful objects. Kristiansen (Reference Kristiansen1987) has developed this argument for metal production in Scandinavia during the Bronze Age.

Although the characteristics of archaeological evidence from Montale makes it difficult to assess whether textile production in general, and spinning in particular, could have been controlled by an emerging Terramare elite, the timing of this specialised manufacture, which began much earlier than the emergence of settlement hierarchies in the Terramare area (at the end of the Middle Bronze Age 3), suggests that Bronze Age wool production, as documented by Montale, was not being channelled into manageable ‘bottlenecks’. A bottleneck, such as attached specialisation or dominance of trade, is a point of restriction in the commodity chain, which would allow elites to channel the flow of critical commodities (Earle et al. Reference Earle, Ling, Uhnér, Stos-Gale and Melheim2015). More case studies are needed, but one could tentatively suggest that patterns of Terramare textile making and trade might have been rather deeply affected by external factors which determined profitability.

All in all, the huge quantity of spindle whorls recovered at Montale argues strongly for intensive yarn production. Additionally, considering the limited size of the settlement (c. 1 ha and a probable maximum population of c. 130 inhabitants, cf. Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015, 167), a conspicuous part of the local population probably participated in such production. What can be said about the social context of this textile production, as evident at Montale? The lack of material culture signalling the existence of a well-defined elite is a recurrent issue in studies of the Terramare area attempting to assess modes of political and economic management and control (eg, Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015; Pacciarelli Reference Pacciarelli2016). Our proposal, as far as textile specialisation at Montale is concerned, is to envisage a community-based (corporate) entrepreneurship. As mentioned, the existence of a corporate structure in Terramare settlements has also been proposed in order to explain the conspicuous and recurrent collective effort that must have been put into, among other things, digging and maintaining the large ditches and corresponding embankments normally surrounding local settlements (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015, 168). A similar coordinated and communal effort has also been proposed for the construction of other features from the plain such as the imposing ritual basin of Noceto, Parma province, (Bernabò Brea & Cremaschi Reference Cremaschi and Ferrari2009; Cremaschi & Ferrari Reference Cremaschi and Ferrari2009, 106–7) or irrigation systems dated to the end of the Middle Bronze Age (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2015, 168). Even dismissing the hypothesis of attached production, it seems unlikely, given such premises, that single household or individual workshops actively pursued manufacturing activities for private wealth accumulation, as is suggested for independent, market-driven production models (Brumfiel & Earle Reference Brumfiel and Earle1987b).

Rather, the high quantity of spindle whorls at Montale suggests a broad, community-based specialisation, in which many spinners (or a large number of community members) participated. We propose that the characteristics of the archaeological record fit well with what has been called a ‘community of practice’. Relying on an anthropological study of modern work groups (Wenger et al. Reference Wenger, McDermott and Snyder2002), communities of practice can be defined as close-knitted groups of specialists, often situated socially in single environments, communicating and sharing knowledge, exchanging services, training novices through social learning systems, and, at times applying practice-based social pressure to ensure that all participants conform and that expected outcomes are achieved (Wenger Reference Wenger2010; compare Santacreu et al. Reference Santacreu, Vidal, García and Calvo2014). As to our concern with Terramare social organisation, in a community of practice, leadership and practice management ought to acquire an internal intrinsic legitimacy that enables the establishment of effective organisation (eg, Wenger Reference Wenger1998a; Reference Wenger1998b, 72–9). Such a community of practice can result in several characteristics, including concentrated specialist activities in one locale, standardised production methods, and a localised competitive advantage defined by ‘the regime of competence’ that social learning and shared knowledge create (cf. Wenger Reference Wenger2010). Certainly the concentration of spinning tools at Montale easily fits the first criterion. The homogeneity of shapes within some of Montale’s types of whorls (see Fig. 4), suggests also that the technology used in specialised textile production might have been produced in a standardised way (by the very same communities of practice or, perhaps, by workshops manufacturing these tools for the rest of the community?). Although further studies and analyses are necessary to test such hypotheses, the evidence hints at coordinated productive activities within the village. Looking specifically at weaving practices, a community of practice model has been also proposed to interpret the archaeological evidence for the Terramare loom weights (Sabatini in press). A comparative analyses of the available evidence from various sites of the Po plain and of the neighbouring Garda lake/Trentino area suggests that changes – in particular in the weight of the loom weights – occur contemporarily over the Po plain, but not in the Garda lake/Trentino area. In other words, weaving practices might not have been exclusive in the various villages, but rather shared widely. The known Terramare loom weight assemblages suggest that looms with unevenly heavy weights characterise Middle Bronze Age 2, while relatively light and similar weights generally distinguished Middle Bronze Age 3 and Recent Bronze Age 1 (cf. Fig. 1) assemblages. During Recent Bronze Age 2 heavy items of 1–2 kg appear instead the most common loom weights. Although further research is necessary to provide a secure reconstruction of Bronze Age weaving traditions on the plain, it seemed reasonable to envisage Terramare weaving as a dynamic activity developed by communities of specialists who networked broadly across Terramare villages, actively negotiating and developing regional weaving technologies.

CONCLUSIONS

In addition to the well-known metal trade, textiles must have been important commodities in the Bronze Age generally (eg, Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015; Reference Frei, Mannering, Vanden Berghe and Kristiansen2017; Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen2016; Vandkilde et al. Reference Vandkilde, Hansen, Kotsakis, Kristiansen, Müller, Sofaer and Stig Sørensen2015). Textual evidence from the Aegean and the Near East documents how textile manufacture was closely supervised, involving the interplay of resource procurement and labour specialisation. The lack of written evidence and the poor archaeological preservation of textiles has limited prehistorians’ ability to capture the organisation of Bronze Age textile economies outside the Mediterranean. Rather, outside this region, attention must focus on textile technologies and their tools, such as spindle whorls, which can be studied in terms of settlement and household variability as a means to describe labour specialisation and its multiple roles in the political economy (Sabatini in Reference Sabatinipress). The evidence from Montale suggests that textile crafts could have consituted a major settlement specialisation based on the capacities of local population to exploit environmental and human resources, including specialised labour, and – as to wool production – management of large herds. Montale’s community might, therefore, have managed production to meet wider continental demands, as documented for northern Europe, where woollen clothing, at least during the 14th and the 13th centuries BCE, was used apparently without convincing signs for local wool production (Bergerbrant in press; Kristiansen & Stig Sørensen in press).

But what was the political significance of specialised textile production at Montale? We propose a simple model that would help explain the pattern of textile specialisation in the broader context of what is known of the local communities’ socio-political organisation (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009a; Reference Cardarelli2014; Reference Cardarelli2015). Terramare societies appear to have been oriented towards exploitation of their immediate territories with surplus productions in exchange for non-local commodities. Probably, already from Middle Bronze Age 3 (Fig. 1), a number of Terramare settlements employed irrigated agriculture (eg, Cremaschi et al. Reference Cremaschi, Pizzi and Valsecchi2006, 89; Vanzetti Reference Vanzetti2013, 271–2), which must have involved fairly large-scale capital improvements. In order to defend their substantial investments and, most likely, the products of their labour, Terramare societies constructed their fortified settlements and imported metals for harvesting tools, weapons to defend their land, and elaborate ornaments and ritual objects (see Carancini Reference Carancini1997; Marzatico Reference Marzatico1997) suggesting a hard-working but sophisticated society. To obtain unavailable raw materials such as metal, export products were essential. Montale, despite its limited size, has already attracted attention as applying a Thiessen polygon model indicates that it dominated an unusually large territory of 2200 ha, when compared with the average (260–890ha) for the neighbouring sites of the province (Cardarelli Reference Cardarelli2009c, 43). Access to such a wide landscape might have allowed the Montale community to carry out both an intense agricultural production and animal husbandry at close range. In addition, Montale is situated in proximity to the southern margins of the plain, thus close to potential summer pastures offered by the Appenines which were abundantly used for sheep farming during Roman times, for example (Corti Reference Corti2012). Combined with the archaeological evidence for intense sheep/goat husbandry (De Grossi Mazzorin & Ruggini Reference De Grossi Mazzorin and Ruggini2009), our hypothesis is that the favourable regional environmental conditions and the likely capacity for development of communities of practice in spinning and weaving created the necessary local comparative advantage that made surplus production and exports in wool feasible.

The evidence from Montale suggests that the role of specialised textile production in the European Bronze Age was highly variable and dependent on the broader political economy in which it was imbedded. This focus on variability is critical to understanding different forms of specialisation generally and the wool textile economy specifically. We encourage the investigation of textile production as a means by which to study alternative pathways for social formation, some emphasising hierarchy while others possibly remaining resistant to elite control. As it must be documented archaeologically, during the Bronze Age, communities and regions appear to have engaged in continent-wide trade in many commodities in quite different ways and with quite different effects.

Acknowledgements: Andrea Cardarelli kindly entrusted the archaeological material presented here to Serena Sabatini. His contribution provides the broad perspective on the Terrarmare culture. Access to the archaeological material was provided by the Civic Archaeological and Ethnographical Museum of Modena and generously assisted by Gianluca Pellacani, to whom goes our deep gratitude. Tim Earle, who invaluably contributed to the theoretical framing, was brought into the project, while a Visiting Scholar at Gothenburg University (May 2016). We are grateful to Helene Whittaker for reading and commenting on earlier drafts and to Kristian Kristiansen for engaging discussions and comments and to the anonymous reviewers.

This project was supported by the European Research Council under Advanced Researchers Grant no. 269442 – Travels, Transmissions and Transformations in Temperate Northern Europe during the 3rd and 2nd Millennium bc: The rise of Bronze Age societies; The Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences under Project Grant P15-0591:1 Bronze Age Wool Economy: Production, trade, environment, herding and society; and Birgit och Gad Rausing Foundation under project grant Bronze Age Textiles in Southern Europe: Production, use, and exchange.