No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

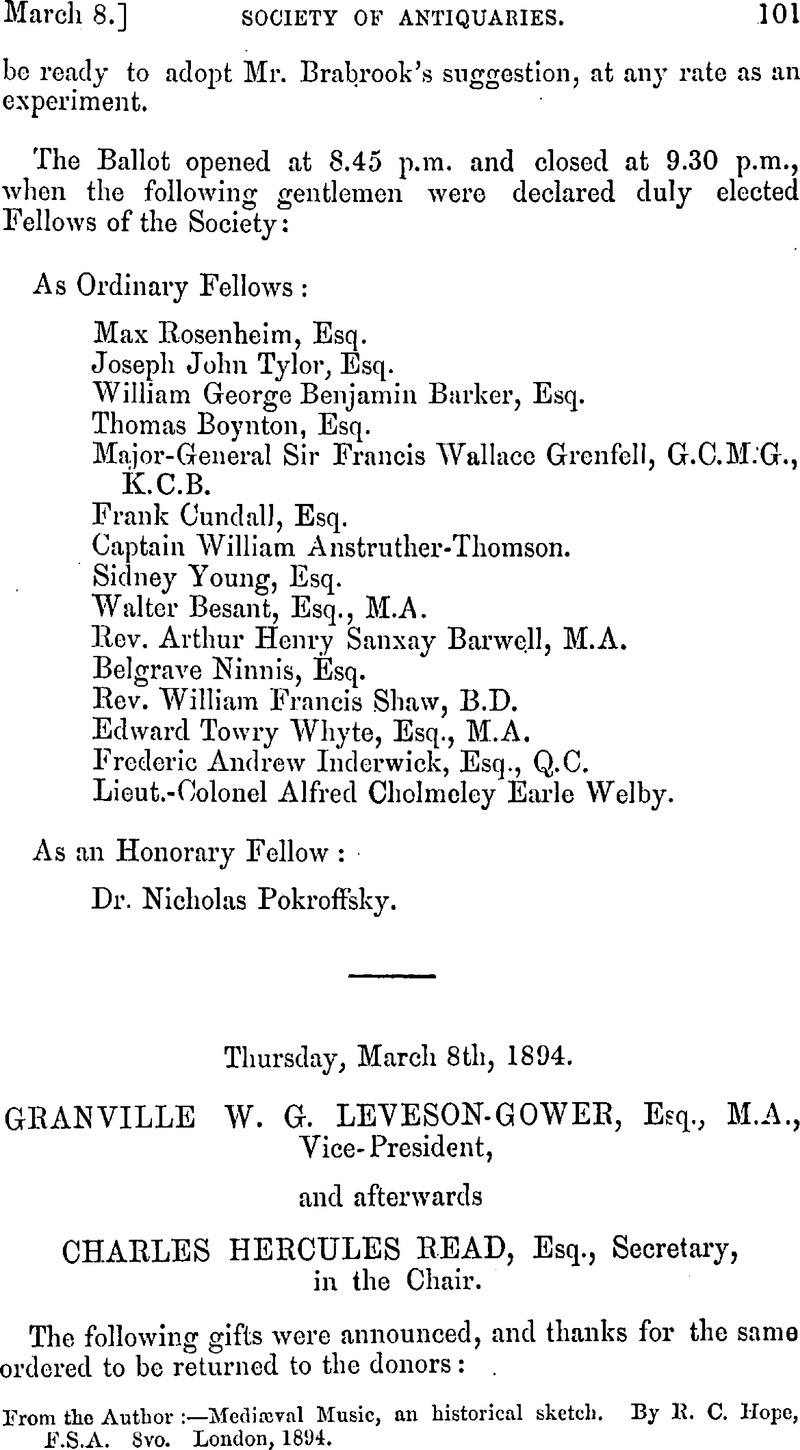

Thursday, March 8th, 1894

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 May 2010

Abstract

- Type

- Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1895

References

page 102 note * Paris, 1890, p. 242.

page 105 note * Early English Text Society, 1870.

page 106 note * Record Office Certificates of Guilds, No. 445.

page 107 note * De Origine Festorum, Christianorum (Liguri, 1612), 88.

page 113 note * MS torn here.

page 115 note * MS torn here.

page 116 note * Public Record Office : Chancery Guild Certificates, No. 445.

page 118 note * There is a hole in the MS. where the blanks occur.

page 119 note * Proceedings, 2nd S. xiv. 261–267. For the cemetery see Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, xii. 365–374.

page 119 note † Since first writing these notes I have examined both at Carlisle.

page 119 note ‡ Proc. xiv. 262–7.

page 120 note * C. vii. 310. Lapridarium, No. 797.

page 120 note † Ptolemy ii. 3, 4, ii. 5, 7, ii. 6, 22, and C.I.L. v. 810.

page 120 note ‡ As I have said elsewhere, I doubt if the names in the Notitia (l.e.) which follow after Amboglanna are the names of the stations on the wall west from Birdoswald. Certainly this Tunnocelum seems not to have been per lincam valli. The sequence of names in the list is Aballaba, Congavata, Axelodunum, Gabrosentum, Glannibanta, Alione, Bremetenacum: Aballaba, and Axelodunum were at Maryport and Papcastle, Bremeteuacum was at Ribchester, and Tunnocelum would naturally be one of the not few intervening forts.

page 120 note § Hirschfeld, Westdeutsche Zeitschrift, viii. 137.

page 122 note * There is a story that this particular stone was brought ns ballast from Nantes, but I am inclined to think the Aberavon provenance the true one. The stone has been published C.I.L. vii. 1159 (cf. Eph. vii. 1098), and Westwood, Lapid. Wattiae, p. 42.

page 124 note * Proc. 2nd S. xiv. 313.

page 124 note † The Travels of Nicolo Conti in the East, edited with other accounts by Major, R. H., in India in the Fifteenth Century, Hakluyt Society, 1857 p. 30.Google Scholar

page 125 note * The Origin of Metallic Currency and Weight Standards, University Press, Cambridge, 1892, p. 72.Google Scholar

page 125 note † See C. W. King, The Natural History of Gems, 1870, p. 320.

page 126 note * I have seen one, however, which was shown me by Mr. Franks, in the British Museum, measuring nearly an inch in the longest diameter.

page 126 note † DrRoyle, (An Essay on the Antiquity of Hindoo Medicine, London, 1837, p. 103)Google Scholar hints at the connection of the terms ‘Beli oculus’ and ‘billi ke ankh,’ as if ‘Beli oculus’ (which according to Mr. King was an eye-agate) were possibly a Latin adaptation of the Indian name. As Sir Henry Yule and Dr. Burnell (A. Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases, 1886, p. 134) say, this may be only a coincidence, though if not a coincidence it might point to the Indian ‘billi ke ankh’ being the same stone ns Pliny's ‘Beli oculus,’ which Mr. King thinks was an eye-ngate. ‘Billi ke ankh’ may, however, be merely a translation of the European term ‘cat's-eye.’

page 126 note ‡ ‘Beli oculus albicaus pupilltim cingit nigram, e medio aurco fulgore lncentem. Hæe proptor spociem sacratissimo Assyriorum Deo dicatur.”—Nat. Hist., lib. xxxvii. cap. 55.

page 127 note * The Natural History of Gems or Semi-Precious Stones, by King, C. W. M.A., London, 1870, p. 321.Google Scholar

page 127 note † Anselmi Boctii de Boodt Brngensis Belgae … Gemmarum, et Lapidum Historia, Hanoviæ, probably printed in 1609, p. 126, cap. xcix.

page 127 note ‡ Hieronymi Cardani Medici Mediolanensis, de Subtilitate, Norimbergae, 1550, p. 170Google Scholar, Liber Scptimns : ‘Multum ab hoe pseudoopalus degenerat, candidus hie est ot nitet, sed non perspicnus, ocnlum vocant catti sou felis.’

page 127 note § Garcia ab Horto, the Portuguese botanist and physician (Aromatum et Simplicium Aliquot Medicamentorum apud Indos Nascentium Historia, Antverpiæ:, 1567, p. 204Google Scholar, lib. i. cap. liiii.), notes that what Cardunus called ‘pseudopalus’ is the same stone that he himself calls ‘oculus catti.’

page 127 note ‖ By Anselm de Boot, annotated by André Toll. Lyon, 1644. page 290, chap. xxviii.

page 127 note ¶ Compare with this also Musæum Regalis Societatis, by Grew, Nehemiali M.D. (London, 1681), 288Google Scholar, the passage where an eye-like variety of onyx is described as the Beli oculus.

page 127 note ** See Itinerario, first edition, Amsterdam, 15969, page 105, 86th chapter; see also the English translation of 1595, page 134, and the Hakluyt Society's edition of 1885, vol. ii. p. 141.

page 128 note *; See Michaud's Biographie Universelle and Ramusio's introduction.

page 128 note † Primo Volume, & Terza editione della Navigationi et Viaggi racculto gia da M. Gio. Battista Ramusio. Venet., 1563, folio, p. 344.Google Scholar

page 128 note ‡ El libra del famoso Marco paulo veneciano. … Con utro tradado de micer Pogio florentino q trata de las mesmas tierras e yslas. Copy in the British Museum, page xxxii.

page 129 note * River of Golden Sand, London, 1880, ii. 77.Google Scholar

page 130 note * See Voyage au Ouadai, by el Tounsy, Mohammed Ibn Omar, French translation, Paris, 1845, p. 559Google Scholar ; referred to by Prof. Ridgeway, op. cit. p. 46.

page 130 note † See Cat. of Engraved Gems in the British Museum, 1888, p. 9.

page 130 note ‡ Money, not coins, but still better such things or such possessions. The original Greek is εἰ δ⋯ τις παρ’ ⋯μῖν πλεῖστα τοια⋯τα κεκτημ⋯νος εἴη.

page 130 note § Translation by Professor Jowett, B. in The Dialogues of Plato (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1892), ii. 568Google Scholar.